s H a PE s O ur WO rld

abOut tHis bOOk, 13

cElEbrity* P. 17

1900: Death of John Ruskin. Last months and final illness. Call for Westminster Abbey burial, rejected. Coniston lying-in-state and funeral. Tributes: their range and variety. R’s strange and contradictory fame. His ‘brand’. Impact of his passing. Inspiration of activists and utopians. R’s reputation peaks in 1900, inexplicablyfades through early 20th century.

ruskinland, P. 25

Author laments how few call on R for ideas, inspiration. Case for R’s legacy: its piecemeal impact. Hidden landscape of Ruskinland: a whistlestop tour, National Trust to welfare state. Would R have joined Twitter? Difficulty of reading R. Author unapologetic about quoting him. Difficulty of categorising R’s work. Ways R.guides us towards a better life today.

sEEing, P. 35

1. South London, as seen by young R. ‘The plain of Croydon’.

* When John Ruskin was writing his rambling proto-blog Fors Clavigera in the 1870s and 1880s (described in chapter 8), he paused to offer a ‘rough abstract’ of the first letters in the series. I have tried to write these chapter descriptions in similar style.

R’s gift of, joy in, seeing. Neurosis about eyesight. His lifelong habits of observation 2. 1819: birth and childhood idyll. R’s overbearing parents: their influence, good and bad. R on the ‘gifted and talented’ register. What would his school report at 13 predict? R’s love of geology. 3. The Big Draw. Author argues for relevance of R’s ideas about seeing. R’s love of gadgets, cyanometers to daguerreotypes. R’s Instagram account. Author shares R’s disdain for looking but not seeing. Seeing as antidote to busyness. 4. Ruskin family’s travel habits. R’s double brougham. Mapping Ruskinland. 1833: R’s Alpine epiphany in Schaffhausen.

draWing and Painting, P. 53

1. 1837: Oxford. R’s oddity and genius as undergraduate. First love, unrequited. First illness. Awarded ‘double fourth’. 2. R’s facility for drawing, inability to ‘invent’. Drawing as ‘data’. Author advocates for R as great artist. R’s drawing habits. His insights into difficulty of drawing. ‘The universal law of obscurity’. 3. R as critic. 1840: First encounters with Turner. Modern Painters. R’s recipe for great art. Father’s insider trading in artworks. Mike Leigh’s unfair caricature of R. 4.The Pre-Raphaelites: why did R back them? Author praises R’s ability to change his mind. R invents world wide web. 5. R as art teacher. The Elements of Drawing. Modern artists’ debt to R. Ruskin Prize-winners interviewed. Ruskin School of Art today. Author worries about decline of drawing.

building, P. 81

1. 1845:Venice. R’s first two ‘art attacks’: tomb of Ilaria di Caretto; Tintoretto’s Crucifixion. R’s concern for war-torn Venice. His tight

focus and wide-angle views. 2. 1848: Marriage to Effie Gray. Ill omens, myths, pubic hair (or lack of). Emma Thompson’s unfair caricature of R. Author unhappy about persistent obsession with R’s sex life (or lack of). 3. R’s Venice notebooks, accuracy of. R’s diligence as ‘hero of architecture’. His architectural favourites (and least favourites) in Venice. 4. Did R save or doom Venice? ‘La Ruskin’ pizza. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. The Stones of Venice. R defines architecture. Advises how to design your extension. Suburban Gothic. R’s most hated buildings. The Oxford Museum and its ‘happy carvers’. 6. Author puzzles over R’s influence on Gaudí and Frank Lloyd Wright. Why not stop decluttering and start decorating? 7 1852: R and Effie return from Venice. Their loathing of suburban existence. Glen Finglas: Millais and Effie thrust together. 1854: Annulment. landscaPE and naturE, P. 117

1. 1858: France, Switzerland and Italy. R’s appearance and personality in his late 30s. Turner bequest: two myths busted. R’s qualms about Turner. His ‘unconversion’. Art attack #3:Veronese in Turin. ‘The Law of Help’. 2. R’s love of the Alps, dislike of alpinists. Geology and science. John Muir, differences and similarities. Charles Darwin, differences and similarities. Matterhorn’s impact on British builders. 3. Beauty of Monsal Dale, destroyed by railway, later restored. National parks. Trains, unexpectedly praised by R. R as cultural pillar of modern Lake District. Author sits on Ruskin’s Seat, Brantwood. 4. Ruskin Land: rural compromises and contradictions. Sustainability. 5. R compares Bradford to Pisa. R’s influence on town planning, garden cities, suburbs and villages. Author speculates about R’s view of green belt. R on ‘nimbyism’.

5. 1884: ‘The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century’. R and Al Gore compared. R’s warnings proved right. 6. Los Angeles. The Ruskin Art Club’s ‘applied Ruskin’. R-inspired campaigns, from Thirlmere to zipwires. The ‘genteel’ National Trust.

WOrk and EducatiOn, P. 149

1. Unto This Last, the 21st-century furniture workshop; Unto This Last, R’s 19th-century polemic. 1860: R switches from art to economic criticism. Controversy, prefigured in earlier works. R’s influence on Labour MPs, Gandhi etc. Author’s Brantwood epiphany. Parallels with 2008 financial crisis. 2. R’s work ethic and workaholism. ‘The Nature of Gothic’ and the spirit of the worker. 1854: R as teacher at Working Men’s College. ‘Happy carpenters’. 3. 1858: Rose La Touche: first meeting. 1866: Ill-judged proposal of marriage. 4. Author addresses R’s liking for young girls. 1864: ‘Of Queen’s Gardens’: 19th-century progressive influence, 20th-century feminist outrage, paradox explored. Girls’ schools inspired. 5. The Ruskin curriculum. R’s detestation of the ‘three Rs’. Vocational education. 6. Schools that followed R’s lead. Integrated education today. 7. The Working Men’s College today: life-drawing to English as a Second Language. 8. R’s ideas spread to the workplace. Robots: author wonders if R would approve. Work by Ford Madox Brown.

craft P. 185

1. John Lewis and the ‘Ruskin House’ look. R and William Morris not the Simon and Garfunkel of craft. Morris: his R-inspired path,

where it diverged. R’s preference for Morris’s objects over his politics. 2. 1864: Death of R’s father. R’s 1830s prejudices. The Eyre affair and other imperialist blots on R’s legacy. 1870: speech on England’s colonial destiny and impact on Cecil Rhodes. 3. 1869: Rose La Touche offers no solace to R. Art Attack #4: Carpaccio. 1870: R’s return to Oxford. Success as lecturer and public fame. Fors Clavigera: R’s proto-blog, its meaning and crazy genius. 1871: R’s ominous illness. Brantwood purchased. R as hands-on landowner. Brantwood as hub for craft. Author’s link to Arts and Crafts. The US Arts and Crafts connection. 4. Rootedness of modern craft. Ruskin inside Land Rovers, beer, bags. 5. Steampunk, Steve Jobs and software. New notions of work with our hands. 6. 1874: R’s road-building experiment. His intellectual chain-gang, including Oscar Wilde.

WEaltH and WElfarE, P. 223

1. Was R a ‘leftie’? His attitude to wealth. His definition of ‘illth’ and modern examples. R’s philanthropy. 1877: The Guild of St George, R’s ‘omni-charity’. St George as anti-capitalist symbol. R’s ‘glass pockets’. 1875: Rose, decline and death. 2. R’s séances. The Guild’s quixotic schemes. R’s utopianism. Author visits current Master of the Guild.Ways it lives up to R’s vision.The Ruskin collection, Sheffield. How R caters to our hunger to reconnect work, nature, craft. 3. Arnold Toynbee, Toynbee Hall and the universities movement. Thomas Horsfall, the Ancoats Museum and modern descendant.. R hates Manchester. 4. The path from R to the welfare state, via Beveridge, Attlee, Hardie. Surprising absence of R from modern Labour party; why R would not have minded. ‘Darkness voluble’. 5. 1870: R overworked, underappreciated.

The Whistler trial. R on opium. Idealism versus pragmatism. 1881: Death of Thomas Carlyle; R’s breakdown. 1883: Second, ill-fated stint as Oxford professor. ‘Baby-talk’ to Joan Severn. 1888: Final trip to Venice.

finisH, P. 259

1. Author visits Ruskin, Florida. McMansions and manatees.

2. How Ruskinites made it to Florida, and why. 3. Impossibility of being a true Ruskinian. The Ruskinland network. Author describes change in his attitude. Basil Fotherington-Thomas and Kenneth Clark evoked. Author makes final case for selective revival of R’s legacy. 4. R the man survives in Ruskin the place.

5. Author shares R’s difficulty in finishing. Finishes nonetheless.

draWings and WatErcOlOurs by ruskin in cOlOur PlatE sEctiOn bEtWEEn PP. 146 & 147

acknOWlEdgEmEnts, P. 277

furtHEr rEading, P. 280

list Of illustratiOns, P. 284

nOtEs, P 286

indEx, P. 296

This book tells the story of who John Ruskin was, how he lived, and what he was like.

It is not exactly a biography. I have relied on some vastly betterresearched recent books about Ruskin’s life, which I list at the end of the book.

I have set his work in the context of his astonishing life, though, if only to answer the question most frequently posed when I mention John Ruskin. Grasping for a vague memory of something half-heard in the classroom or lecture theatre or glimpsed in a museum or library, people ask: ‘Wasn’t he the guy who…?’

At the same time as sketching Ruskin’s life and career, I try in this book to open a new and different window onto Ruskinland, through interviews with, visits to and research into the people, places and institutions of the 21st century where Ruskin’s influence is still alive, and lively. They range from Brantwood in the Lake District, via Switzerland and Italy, to the Florida community of Ruskin, whose tenuous but real links with Ruskin the man I describe in the last chapter.

In providing an outline of Ruskin’s prodigious life, I have tried to follow his guidance to students on drawing a tree. In Exercise VI of his manual The Elements of Drawing, he wrote: ‘Do not take any trouble about the little twigs, which look like a confused network or mist; leave them all out, drawing only the main branches as far as you can see them distinctly’. That said,

I have occasionally digressed to describe a particularly interestinglooking twig.

The book navigates a rough chronological path through Ruskinland, from Ruskin’s birth 200 years ago, via sections named for some of the themes that marked the different phases of his work and thinking.

These were not discrete stages of his career, though. Ruskin built a web of connections over decades. Some parts of the network are visible already in his very early work. To contemporaries, for example, his switch to social criticism from art in the 1860s appeared to be entirely fresh and surprising, but the seeds of his later views on economics and work were present even in the fairy tale The King of the Golden River, which he wrote for Effie Gray, his future wife, when he was 22 and she was a teenager. That is why I will occasionally leap forward to pick up a lecture or a piece of writing from later in his career or jump back to refer to something he had already said, written or done.

Ruskin sometimes found himself at odds with his earlier self and struggled to reconcile firm convictions he had laid down in his twenties with the more doubting, better-informed judgments of his middle age. He was, in other words, just like the rest of us, with the crucial difference that his early thinking had been published.

Three tortured emotional relationships, or their shadows, pursue Ruskin through his life and through this book – his unrequited love for sherry heiress Adèle Domecq, his short, dysfunctional marriage to Effie Gray, the annulment of which was the source of most of the myths and rumours about his sexuality, and his obsession with, and ill-fated courtship of, Rose La Touche.

Ruskin was extraordinarily well-read. He was also all too aware of the quantity of ideas lying just beyond the border of the many things he already knew. The realisation that if he could

ABOUT THIS BOOK

not make the connection between them, others might not even bother, was probably one of the frustrations that drove him mad. He also suffered the blight of any writer who embarks, inspired, on a project that leads off into a perplexing number of different byways.

In a letter from Venice to a friend in 1859, he grumbled that ‘one only feels as one should when one doesn’t know much about the matter’. Ten years later, he described the same problem in a letter written in Verona, as he researched different architectural styles:

I am like a physician who has begun practice as an apothecary’s boy, and gone on serenely and not unsuccessfully treating his patients under rough notions, generally applicable enough – as, that cold is caught sitting in a draught, and stomach-ache by eating too many plums, and the like – but who has read, at last, and thought, so much about the mucous membrane and the liver, that he dares not give anybody a dose of salts without a day’s reflection on the circumstances of the case.1

As I slid deeper and deeper into research for this book, I felt some sympathy with that complaint.

St. Albans, September 2018

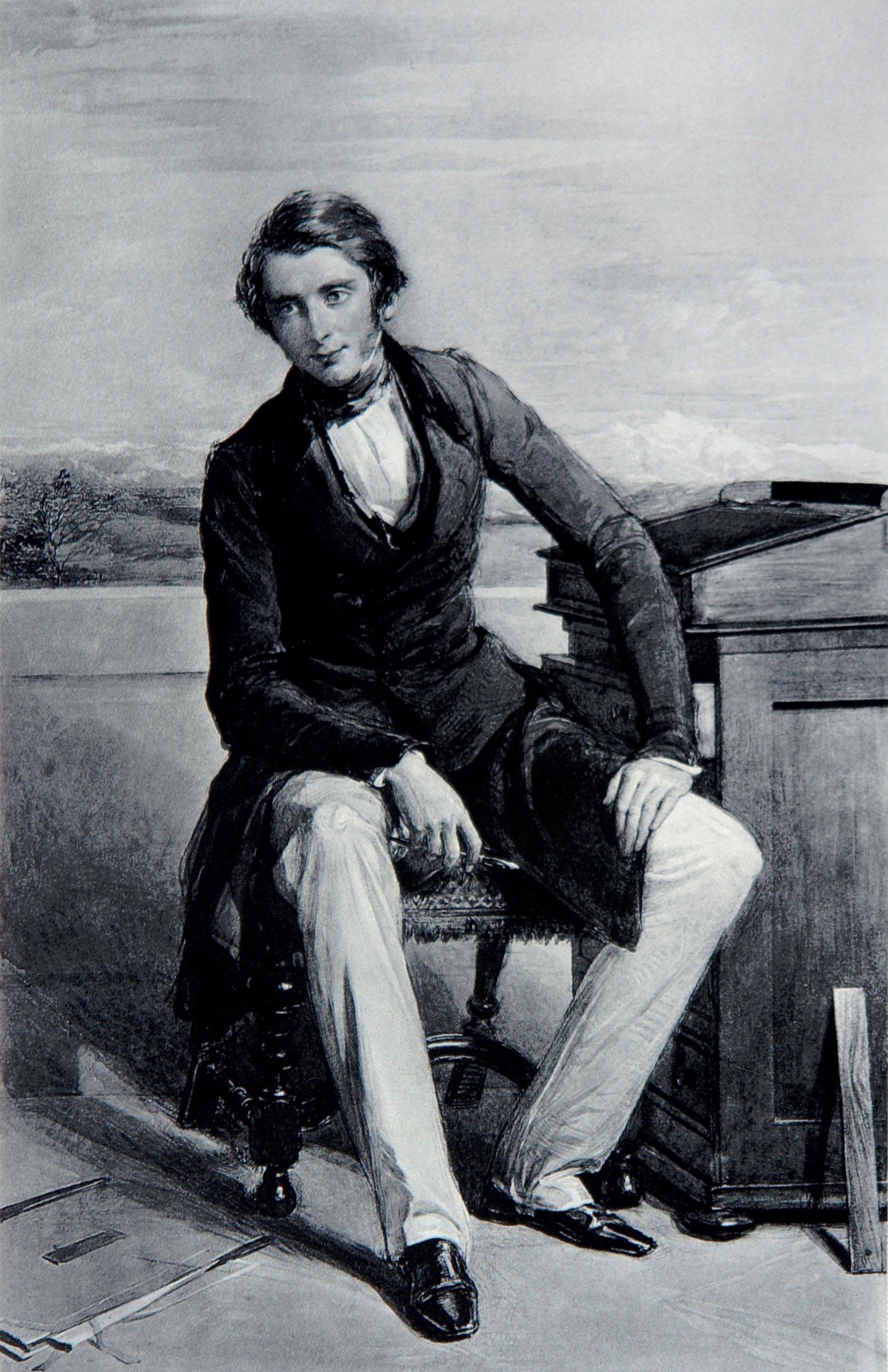

The Author of Modern Painters, 1843 Ruskin at 24, in the first flush of celebrity. Photogravure after watercolour by George Richmond

There is only one place where a man may be nobly thoughtless –his death-bed. No thinking should ever be left to be done there.

(The Crown of Wild Olive)

It was influenza, the signature disease of the connected modern world – which John Ruskin had so often attacked – that finally did for the towering intellect of the 19th century.

The two-year epidemic that had affected the Americas, Australia and much of Europe reached Ruskin’s rambling home at Brantwood, overlooking Coniston Water in the English Lake District, in January 1900.

Ruskin had passed the preceding months as a frail invalid, sequestered in his bedroom from which he could enjoy the panoramic views of the mountains. The virus had taken hold in the village of Coniston. Despite the relative isolation of Brantwood’s distinguished owner, once a servant introduced it to the house, there was little his devoted staff could do to protect him.

Ruskin ate his last proper meal – sole, pheasant and champagne – on 18 January.1 He died in his sleep at 3.30 pm on Saturday

20 January, surrounded by paintings by J. M. W. Turner, whose reputation he had helped forge. He was 80 – though with his stoop and Old Testament beard, he could have passed for 100 –and perhaps the most famous living Victorian apart from Queen Victoria herself.

Ruskin’s high-profile friends and London society contacts immediately called for his remains to be interred in Westminster Abbey, alongside Britain’s great poets and artists. His wishes prevailed, however. He had wanted to be buried in the village graveyard in Coniston, across the lake from Brantwood, next to the simple church erected in 1819, the year of his birth.

‘In pitiless weather – driving rain and high winds – the body… was brought from his home’ to St Andrew’s Church ‘in a plain hearse, drawn by two horses’, for a lying in state, wrote a special correspondent for The Standard – falling into the trap of ‘pathetic fallacy’, the phrase Ruskin coined for the attribution of human emotions to natural phenomena. Four carriages accompanied the body, one bearing his motto ‘To-day, to-day, to-day’.

The sage’s stern, bearded face, sketched by an artist for the illustrated weekly, The Graphic, was visible through a glass panel in the oak casket. ‘It was remarked,’ wrote the Guardian’s correspondent, ‘that Mr Ruskin’s hair retained its singular yellow-grey colour.’

By that evening, ‘not only was every vestige of the coffin… entirely hidden in a mass of exquisite flowers,’ continued The Standard, ‘but the choir seats, the lectern, and even the front of the pulpit, were similarly covered.’ Among them was a wreath sent by the 82-year-old doyen of Victorian artists George Frederic Watts, made of leaves cut from a laurel tree in his garden. It was an honour he had previously afforded to only three other giants of Victorian culture on their passing: the painters Frederic Leighton

and Edward Burne-Jones, and the poet Alfred Tennyson. All had known and admired, or been admired by, Ruskin.

The Coniston railway had to lay on additional services to carry the floral tributes and the mourners, who crowded the church and churchyard for Ruskin’s funeral on the Thursday following his death. It was an irony that the writer, a regular user of railways but also a violent opponent of their spread into the Lake District, would probably have appreciated. Local hotels, unprepared for midwinter tourism, were overwhelmed.

Spinsters from the district, devoted to Ruskin’s principles of craft, made the funeral pall. Over the initials ‘JR’, it featured a wreath of wild roses and the words ‘Unto This Last’, the title of the fiery polemic with which, in the 1860s, Ruskin, then bestknown as an art critic, had launched himself into political, economic and social criticism.2

It was a simple ceremony, including a hymn specially written by Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley, who, inspired by Ruskin’s views on conservation, had helped found the National Trust five years earlier. ‘There was no black about his burying, except what we wore for our own sorrow; it was remembered how he hated black,’ wrote William Gershom Collingwood, Ruskin’s friend, secretary, disciple, biographer and now pall-bearer alongside William Wordsworth’s grandson.

Ruskin, who had delighted, informed, harangued and annoyed his fellow Victorians for much of the mid-19th century, in lectures, articles and books that later filled 39 volumes – including one for the index alone – had lived his last decade in near-silence, tortured by what would now probably be diagnosed as bipolar disorder. If anything, though, his reclusiveness and the abrupt curtailment of his public appearances in the 1890s had only increased John Ruskin’s celebrity.

It was a strange and contradictory sort of fame. As early as 1858, Ruskin had noticed with grave concern ‘the stern impossibility of getting anything understood that required patience to understand’ as mass production of books took hold.3 He had fought to preserve the sanctity (and higher price) of quality editions of his work, making sure they were available only by post from his publisher and protégé George Allen. But Ruskin’s later popular reputation rested on the success of cheaper versions, issued from the late 1880s by the canny publisher who expanded his range to include decorative editions, in high demand for presentation as gifts or prizes.

These bestsellers rebuilt his fortune. The great polemicist against ‘illth’ – his word for misused riches – had assiduously, some said recklessly, given away much of the legacy of his winemerchant father and spent much of the rest continuing to purchase objects, artworks, and books. Those items he had not in turn donated to schools and museums crammed his rooms at Brantwood.

Ruskin had also suffered the equivalent of two tabloid scandals – and found the taint as hard to expunge as any modern celebrity would. The annulment of his marriage to Effie Gray ‘by reason of incurable impotency’ – and her subsequent happy, and productive union with John Everett Millais – had led to smears and rumours about the reasons for the non-consummation. It later contributed to the collapse of Ruskin’s ill-starred attempts to marry the much younger Rose La Touche, the love of his life.

Ruskin had also fought and lost a court battle with James Abbott McNeill Whistler after libelling the artist with a characteristically pungent – but uncharacteristically out of tune – assessment of his impressionistic work.

The cumulative effect of these humiliations exacerbated his

mental turmoil. His breakdown in 1889 in effect ended his public career.

In spite of his reclusiveness, though – and partly because of his oddness and notoriety – by the end of his life Ruskin had become what he most abhorred: a tourist attraction, bringing visitors to the Lake District on the very railways he had condemned. In the last decade of his life at Brantwood he became in the words of the devoted modern Ruskinian James Dearden ‘something of a peep show’ as people trekked north to see him.4 Those travellers who could not get a glimpse, let alone an audience, could choose from an array of postcard images of the man, or his house, peddled locally.

Ruskin had been a target for caricaturists since at least the late 1860s. By now others were happy to appropriate his name for their own purposes, with or without his endorsement. Ruskin ceramics, Ruskin linen and lace products, and Ruskin fireplaces were on the market. La Calcina, the Venetian osteria where Ruskin had taken rooms in the 1870s, started to issue postcards boasting of the association (the hotel that replaced it still subtitles itself ‘Ruskin’s House’). Most bizarrely, the Lewis Cigar Manufacturing Company of Newark, New Jersey, introduced a premium cigar into its range in 1893 called ‘The John Ruskin’, despite his vocal opposition to tobacco-smoking.5

Queen Victoria’s fame owed much to her position; by 1900, Ruskin’s was based on his own voluminous pronouncements on art, craft and architecture, on the environment, economics and education.

In the days following his death, telegrams and letters of condolence poured into the sage’s Cumbrian retreat. As impressive as the quantity, was the range. The Times obituary called Ruskin ‘the prophet of Brantwood’. Princess Louise, the Queen’s daughter,

telegraphed her sympathy. So did the Duchess of Albany, widow of Prince Leopold, Victoria’s youngest son, whom Ruskin had taught at Oxford and who had become a trustee of his drawing school. The widow of Burne-Jones, one of the Pre-Raphaelite painters supported by Ruskin, wrote of ‘the magic of the master’s personality’. At the same time, the village tailor sent a wreath with a card that read, simply, ‘There was a man sent from God, and his name was John’.6

Ruskin’s death sent ripples well beyond Coniston. The news galvanised the network of societies, established in British industrial cities including Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham and Sheffield during the later years of his life to propagate his thinking.

The Ruskin Union, formed only three weeks after his death to promote the study of his work as ‘at once profound, sympathetic, and generous, and nobly used for the benefit of mankind’, was presided over by Lord Windsor and Lord May, and included various bishops, deans and university professors on its inaugural committee.

By October of the same year, Hardwicke Rawnsley had raised money for a memorial to Ruskin at one of the writer’s childhood haunts overlooking Derwent Water near Keswick – technically the first National Trust property in the Lake District. The memorial also spawned a series of souvenirs, including brassware, toasting forks with the monument as a handle, and miniature replicas of the monument itself.

A campaign to erect a memorial in Westminster Abbey got under way within weeks of his death and a medallion was unveiled in 1902, though Lady Burne-Jones was among those who argued that the critic himself would have condemned a ‘continuation of the system which has already defaced the incomparable walls of the Abbey with modern incongruities’.7

Across Britain, municipalities and individuals sought to commemorate Ruskin by applying his name to roads, schools, and parks. Ruskin Park, near his childhood home in Denmark Hill, was opened in 1907. In the years immediately after his death, Ruskin’s social and economic criticism inspired activists such as Mohandas K. Gandhi, pioneer of non-violent protest and Indian independence. The novelists Marcel Proust and Leo Tolstoy lauded the power and purpose of his prose.

Leather-bound 3- by 4-inch booklets with decorative frontand end-papers, containing the text of lectures or extracts from longer works, were sold as gifts, mainly for young women, a reminder of the writer’s strong progressive influence on the education of girls.

Pioneers and disciples of his thinking – perhaps with cheap editions of Unto This Last or other favoured works in their backpacks – fanned out during the final years of his life and afterwards to found colonies, claim landmarks and establish townships in his name, from Australia to North America. At Ruskinite co-operative communities set up in the United States, Ruskin food was served and Ruskin music played. The most dedicated members of one ill-fated Ruskinian commune in Tennessee sported Tolstoyan bloomers called ‘Ruskin pants’.

Yet the first decade and a half of the 20th century marked the peak of Ruskin’s visible influence. By the middle of the century, Ruskin’s name had faded.

Visiting the Ruskin Museum, then at Meersbrook Park in Sheffield, for a BBC talk just ahead of the 50th anniversary of the great polymath’s death, the writer Lawrence du Garde Peach conducted a vox pop of passers-by: ‘Not one knew that Ruskin was a writer. Not one in 50 knew anything that he had written…. Such is fame.’

This once world-famous Victorian thinker had become an encrusted oddity – ‘some dreary old has-been with a beard’ – unread and largely unknown. Yet, as du Garde Peach, broadcasting in 1950 at the nadir of Ruskin’s reputation, pointed out, ‘he influenced his age, and he has influenced ours. Things might have been even worse if Ruskin had never lived. Let us remember that.’8

I went mad because nothing came of my work.

(Fors Clavigera)

For much of the 20th century, John Ruskin’s reputation seemed as dead and buried as the man himself.

His ideas were quickly overtaken by the industrial, political, economic, military and even artistic forces that ravaged and shaped the century after his death. His contemporary Charles Dickens is often invoked as a writer who would have relished chronicling the 21st century’s excesses. But few now call on Ruskin for ideas or inspiration.

Ruskin’s long-termist, pre-industrial and ruralist ideals seem to have little connection with our city-centred, technology-fuelled lives of instant gratification. For most people, the Victorian age’s best-known, most controversial and most prolific intellectual is still the bearded old has-been referred to in that 1950 BBC broadcast: prudish, aloof, self-righteous, conservative to a fault, and resistant to progress.

Ruskin’s personal motto, stamped on later editions of his

Venice: architecture and history

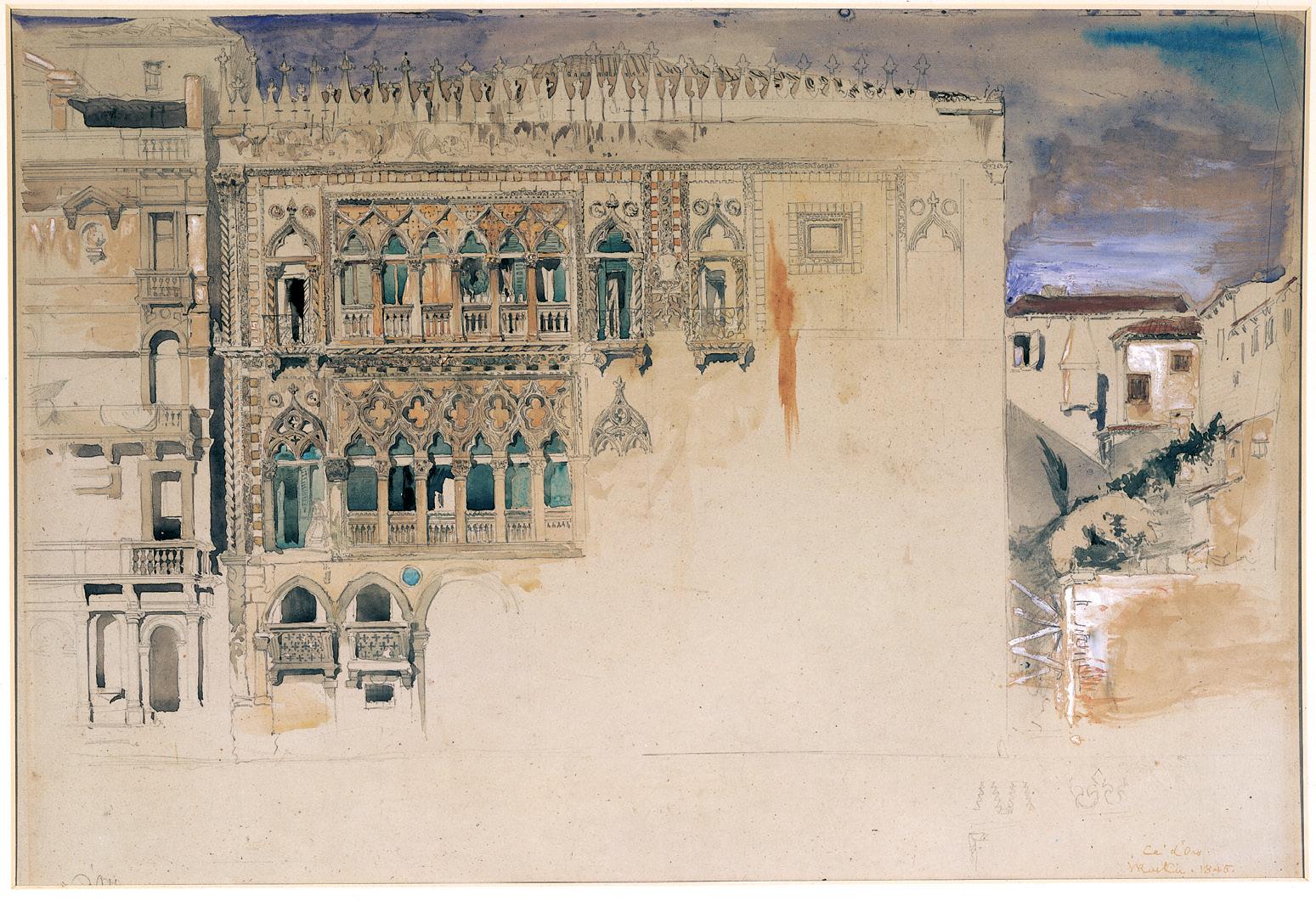

9. Ca d’Oro, 1845 (above). Ruskin was appalled by the clumsy ‘restoration’ under way in Venice when he visited in 1845. He wrote to his father that while he tried to draw the Gothic glories of the Ca d’Oro on the Grand Canal, ‘workmen were hammering it down’.

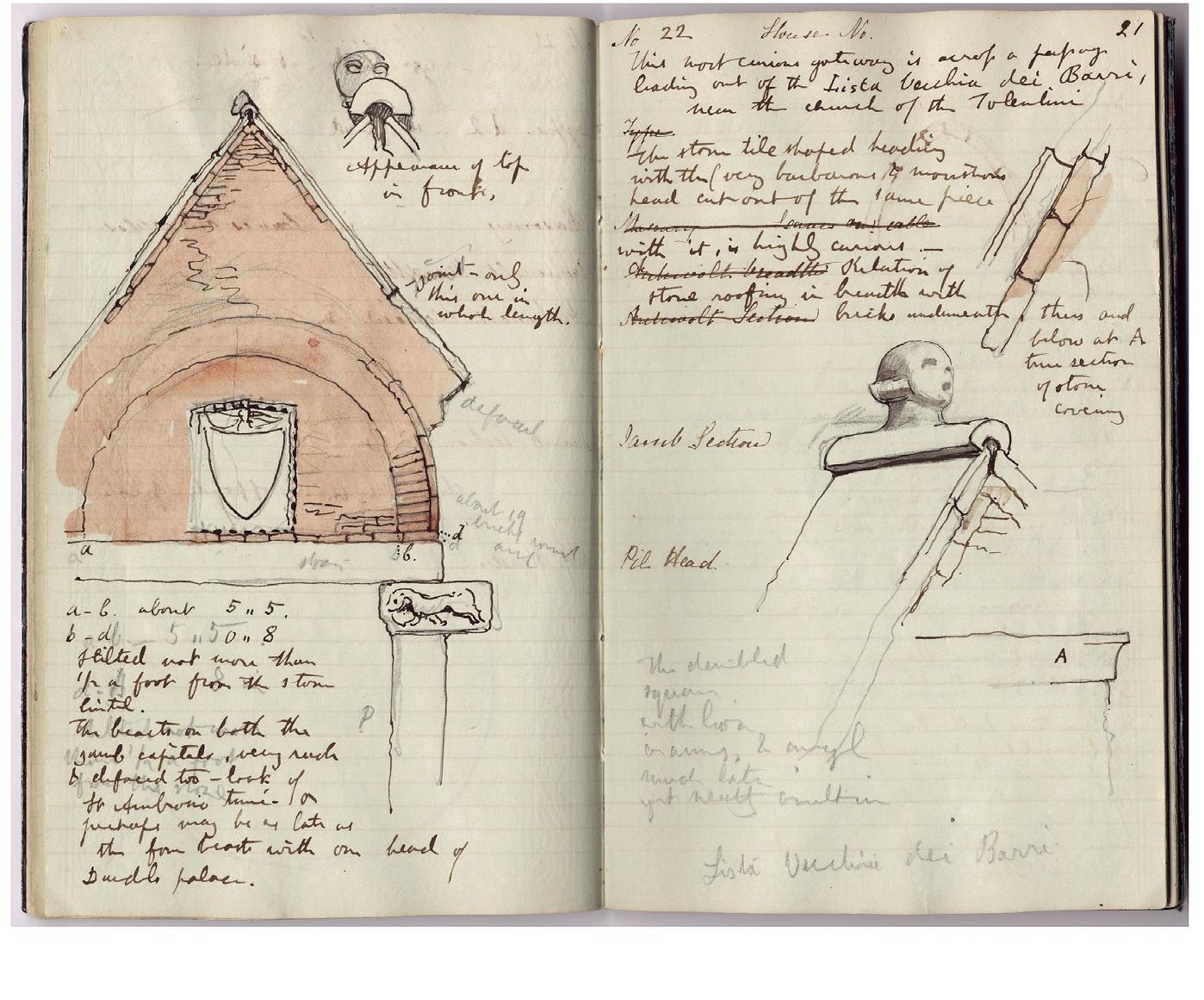

10. Door book,1849-50 (opposite, top). Ruskin’s fascinating Venice notebooks, compiled in all weathers, detailed dimensions and descriptions of the buildings he visited and marked him out as ‘a hero of architecture’, according to one modern critic.

11. Doge’s Palace/San Marco, 1849-52, (opposite, bottom). Venice’s ducal palace – ‘the central building of the world’ to Ruskin – and the neighbouring Basilica of San Marco were key to the writer’s interpretation of Venetian history, and his influential theories about creative work contained in ‘The Nature of Gothic’. This is one of the capitals of the ground-floor arcade of the Doge’s Palace, showing Justice on the left and Aristotle the law-giver in the centre; for Ruskin this demonstrated ‘Justice could only be the foundation of its stability, as these stones of Justice and Judgment are the foundation of its halls of council.’ The path was direct between his architectural writings and his radical politics.

12. Château des Rubins, Sallanches, 1860. Ruskin visited Sallanches often, finding it a perfect spot from which to indulge his love of the Alps. He enthused about the the Aiguille de Varens’ ‘ineffable wall of crag’, depicted in the background of this watercolour. Ruskin planned to write a history of Switzerland, which he thought was a touchstone for its sturdy defence of liberty and its truth to self. At one point in the 1860s he even considered buying some land at Mornex in the Alps and settling there.

13. Vineyard Walk, Lucca, 1874. Ruskin spent much time in the city’s cathedral studying the tomb of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia, but this painting of a nearby village provides spectacular evidence of his wider appreciation for the beauty of the region and a rare exception to the rule that Ruskin often struggled to finish his work.

Abbeville, 136, 256

Abdelal, Alli, 208, 209, 217

Academy Notes (John Ruskin), 152

Acland, Henry, 106, 107, 220 Ahmed, Samira, 166 Albany, Duchess of, 22 Alexander, Francesca, 253

Allen & Unwin, see Allen, George Allen, George, 20, 177 Alpine Club, 123

Amber Spyglass, The (Philip Pullman), 214

Ancoats, see under Manchester Angelico, Fra, 72, 84

Anglia Ruskin University, 62, 277 Apple, 218 architecture and buildings, 81-5, 92-7, 10011, 126

long-lasting, 110 modern architects, Ruskin’s influence on, 108-11

moral quality, 32, 102, 134 skyscrapers, Ruskin’s views on, 108 suburban architecture, Ruskin’s horror of,

35, 105

art, see also drawing and painting commercial pressures, 62 truth, 58, 60, 63, 67, 70, 73, 83

Arts and Crafts, 137, 145, 193, 217, 256, see also craft Frank Lloyd Wright, 109, 111 Lakeland Arts movement, 204-8 William Morris, 185-9

Ashmolean Museum (Oxford), 78, 193, 197 recreation of Ruskin’s School of Drawing, 197

Attlee, Clement, 9, 242-3

Atwood, Sara, 126, 143 automation, 28, 111, 131, 180

Baden, 62

Baker, George, 131 bankers, 153, 168, 181, 182 Barnett, Henrietta, 238

Barnett, Samuel, 238 Barrett, Wilson, 140 Barry, Charles, 103, 246 Baxter, Peter, 255, 257 Beard, Mary, 84 beer, 137, 212 Bell, Margaret, 163 Belli, Gabriella, 97 Bembridge School (Isle of Wight), 169 Berry, Wendell, 145 Beveridge, William, 241-3 bicycles, Ruskin’s condemnation of, 128 Big Draw, The (Campaign for Drawing), 42-3, 76, 235, 271 Birch, Dinah, 160 Blake, Quentin, 87 Blow, Detmar, 256, 257 books, Ruskin’s as gifts or prizes, 20, 23, 165, 177 pricing of, 20, 177, 210

Borges, Jorge Luis, 61 Botticelli, Sandro, 196, 230 Bowerswell (Perth), 89 Boyce, Mary, 144 Bradford, 30, 104, 134, 207, 224-5

Brantwood (Coniston), 39, 41, 49, 50, 93, 10910, 124, 212 modern visitors’ enthusiasm for Ruskin and his ideas, 267 purchase of, and Ruskin’s departure from London, 105, 201-2

Ruskin as active owner of, 129-30, 203-4

Ruskin’s later years there, 17, 20, 21, 37-8 , 47-8, 251-8

Ruskin’s presence felt there, 128-30

Brick Lane (London), 149-50, 178

British Museum (London), 104, 122, 202, 232

Brontë, Charlotte, 68 Brown, Ford Madox, 71, 239 antipathy towards Ruskin and vice versa, 91, 181

Brownell, Robert, 87, 90 Brunswick Square (London), 38

Buckland, William, 54, 125

Bunney, John, 177

Burgess, Arthur, 177

Burne-Jones, Edward, 19, 186, 187, 197, 248

Burne-Jones, Georgiana, 22

Burt, Thomas, 153

Byron, George Gordon, 39

Ca’ d’Oro (Venice), 97

Calcina, La (Venice), 21, 99 ‘La Ruskin’ pizza, 99

Cambridge School of Art, 42, 62, 209, see also Anglia Ruskin University

Cameron, Julia Margaret, 45 Canaletto, 60 capitalism, see economics; illth; wealth Carlyle, Jane, 191

Carlyle, Thomas, 154, 157, 181, 183, 187, 242, 247, 273 death, impact on Ruskin, 251

Edward Eyre, defence of, 190-1

Carpaccio,Vittore, 82, 155, 196, 197, 227, 230

Carshalton, 232

Case for Working with Your Hands, The (Matthew Crawford), 216

Castledine, Steve, 211, 213

Charles, Prince, 137 cholera, 219-21

Christ Church (Oxford), 53, 54, 56, 134

Christ in the House of His Parents (John Everett Millais), 71

Christian Socialism, 106, 157, 181 cigars, ‘The John Ruskin’, 21 cities, 238 garden cities, 134-8, 238 green belt, 138 moral quality, 32 Civilisation (TV series), 265 Clark, Kenneth, 47, 265, 266 coding, see software

Cole, Henry, 158, 194

Collingwood, William Gershom, 19, 82, 90, 124, 202, 221, 232, 252, 256 colonialism and imperialism, Ruskin’s views on, 195

Common Law of Business Balance, 211 competition, 123, 151, 217, 262 twinned with anarchy as law of death, 152 Coniston, 17, 22, 37-8, 44, 124, 128-30, 170, 201-2, 204 connectedness, 33, 72-3, 105, 121, 124, 134, 172, 212, 235-6, 272

Cook, Edward Tyas, 200, 254, 266 co-operation and collaboration (laws of life), 121, 152, see also Law of Help Corbyn, Jeremy, 76, 243, 246 Couttet, Joseph, 86, 92, 122, 124 craft, 109, 185-9, 202-19, 236, 244, see also Arts and Crafts as hands-on pastime, 202 Ruskin’s three-point code, 186 Crawford, Matthew, 216, 217 cricket, 183, 220

Crown of Wild Olive, The (John Ruskin), 17, 207

Croydon, 5, 35, 38, 51, 170, 171

Crucifixion (Tintoretto), 83 Cucinelli, Brunello, 178

daguerreotypes, 45, 50, 60, 97 Darwin, Charles, 191 Darwinism, 107, 125 out-polymathed by Ruskin, 125 data, 59, 60

Dearden, James, 21

Denmark Hill, 23, 36, 54, 86, 87, 113, 125, 163, 190

Derwent Water, 40 Friar’s Crag memorial to Ruskin, 22, 147 design, see architecture and building; Arts and Crafts; craft; software Dickens, Charles, 25, 157, 191, 200, 219 Dickerson, Chad, 216, 217 Dickinson, Rachel, 212, 255 Dickman, A. P., 268 Disraeli, Benjamin, 247 Dixon, Thomas, 169, 199

Doge’s Palace (Venice), 92, 93, 95-8, 103, 256

Domecq, Adèle-Clotilde, 14 , 54-5, 88, 118

Domecq, Pedro, 38, 54 Downs, David, 203, 221, 232 drawing and painting, 39, 41, 42-3, 53-80, 157-60, 197-8, 247-9, 253, see also art; Elements of Drawing as way for Ruskin to calm down, 47, 61 modern shift away from drawing, 77 Ruskin’s drawing exercises, 13, 41, 64, 74, 159, 173, 197-8

Ruskin’s drawing style, 60 Dream of St Ursula, The (Vittore Carpaccio), 196, 229-30 Drew, David, 243-4 Drive (Dan Pink), 175 du Garde Peach, Lawrence, 23-4, 31, 33

Eagle’s Nest, The (John Ruskin), 149, 216 Eastlake, Lady Elizabeth, 87 economics, 150-4, 179, 243, see also illth; wealth productivity, 180-1 education, 27, 157-60 , 163-77 adult education in 21st century, see Working Men’s College curriculum, Ruskinian, 167, 171 for girls, 23, 163-6 free state secondary schools, Ruskin’s influence, 170 ‘three Rs’, 167, 170, 172 vocational, 168 Effie Gray (film), 87 Elements of Drawing, The (John Ruskin), 13, 41-2, 73, 74, 159, 249 Eliot, George, 68 Emerson, Hunt, 183 Empire, British, 100, 194 environment, 98, 99, 117-48, 212, 229, 236 campaigns, 145-6 green belt, 138 humans’ co-existence, 32 Law of Help, 121, 139, 148 pollution, 140-4, 226 Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (lectures, John Ruskin), 139-43, 158, 253; Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth compared, 143 sustainability, 144 Ethics of Dust, The (John Ruskin), 163 Etsy, 216-17 executive pay, 27, 226 Eyre, Edward, campaign to defend, 191

Fall, Richard, 122 feminism, contrasting reactions to Ruskin, 163-6 Ferry Hinksey, 220, 222, 231-2, 237, 272 Field, Frank, 244

Firehouse Cultural Center (Ruskin, Florida), 271 Fisher, Graham, 137-8 Fleming, Albert, 204-5 Folkestone, 255 Fors Clavigera (John Ruskin), 25, 29, 131, 142, 143, 168, 171, 224, 240, 252, 274 launch of series, explanation of title, 198-201 used to launch Guild of St George, 226-8, 231

Forty-Second (42nd) Street (Manchester), see also Horsfall, Thomas Horsfall, The, 239, 241

Fotherington-Thomas, Basil, parallels with Ruskin, 265

Furness Abbey, 159

galleries, see museums and galleries Gandhi, Mohandas K., 23, 153, 192 garden cities, see cities garden suburbs, see cities Gardner, Anthony, 78-9, 195 Gaskell, Elizabeth, 157 Gaudí, Antoni, 108 Geneva, 136

Genever, Kate, 43 Geoffroy, Olivier, 150, 178-81, 205, 209, 215 geology, 44, 45, 54, 57, 65, 91, 105, 108

Modern Painters as required reading for geologists, 126 Ruskin’s obsession with, 41, 124 Gerry’s Bakery (Walkley), 236 Gladstone, William, 116, 190, 247 Glen Finglas, 61, 114, 193 globalisation, 32 Gordon, Aonghus, 171-2 Gore, Al, 143 Gothic style, 33, 36, 100-9, 197, 265 Graham, William Buchan, 132 Gray, Euphemia (Effie), 14, 20, 36, 94-5, 118, 122, 160, 162, 192, 201, 230 falls in love with Millais, 61, 114-16 marriage to Ruskin, 86-92, 111-16, 196

Gray, George, 89

Great Exhibition, 192 Green, Philip, 225 Greenaway, Kate, 59, 253 Guest, Anne, 75 Guggenheim, Peggy, 92 Guild of St George (St George’s Fund), 75, 147, 204, 209, 238, 241, 250, 251, 254, see also Ruskin collection (Sheffield) activities today, 233-7 Big Draw, The, 42-3 coinage, Ruskin’s proposal, 228 commercial failures, 231-2 Companions of, 227, 228, 233 launch of St George’s Fund, 226-9 omni-charity combining Arts Council, National Trust, Save the Children and Friends of the Earth, 229 Ruskin Land, 131-5 Ruskin’s vision for St George’s schools, 167

Hammond, Helen, 174-5, 176 Hampstead Garden Suburb, 238

Hardie, Keir, 242

Harry Potter, 103

Hartley, Ronald, 270

Haslam, Sara, 206

Hayes, John, 245

Heathcote, Edwin, 108

Herne Hill, 35, 36, 39, 55, 113, 230, 235

Hill, Octavia, 146, 174, 238, 241, 251

Hilton, Tim, 190, 200, 273

Hinksey, see Ferry Hinksey; road-building

Hirst, Damien, 70

Hobbs, John (known as George), 86

Hodgson, Roy, 170 Holland, Charles, 110

Hollyer, Frederick, 47 Holt, Edward, 206

Horsfall, Thomas, 239-41, see also under Forty-Second (42nd) Street

Howard, Ebenezer, 136 Howards End (E. M. Forster), 169

Howeson, Anne, 77

Hubbard, Elbert, 207

Hull, Howard, 124, 129, 183, 203, 275 human resources, 183

Hunt, William Holman, 70, 71, 281

Hunter, Robert, 146, 147 hyperrealism, 60

Ilaria del Carretto, tomb of, 82, 230

Iles, John, 131-4, 209, 213 illth, 20, 46, 154, 183, 225-6, 228, 243, see also economics; wealth

Immelt, Jeffrey, 226

India, 23, 153, 192, see also Gandhi, Mohandas K.

Ruskin’s dismissal of Indian art, 194 Instagram, 45

Ruskin as natural Instagrammer, 30 interdisciplinarity, see connectedness Italy (Samuel Rogers), 51, 95 Iteriad (John Ruskin), 40

Jameson, Melody, 270, 273

Jobs, Steve, 218

John Lewis Partnership, 185, 189

John Ruskin College (Croydon), 170-1

John Ruskin Prize, 42, 75-9, see also Big Draw Johnson, Nichola, 44

Kapital, Das (Karl Marx), 187

Kelmscott Press, 188 Keswick, 205, 208

Keswick School of Industrial Art, 205 King of the Golden River, The (John Ruskin), 14, 87

Kingsley, Charles, 157, 191 Kirkby Lonsdale, 210 brewery, 211

‘Ruskin’s View’, 147

Kohler, Walter, 178 Krier, Léon, 137

La Touche, John, 161

La Touche, Maria, 160-1

La Touche, Rose, 14, 20, 55, 82, 160, 232, 250, 254, 256, 269 decline and death, 229-31 first meeting with Ruskin, 118 relations complicated by Ruskin’s annulled marriage to Effie Gray, 195-7

Ruskin dedicates Sesame and Lilies to her, 165

Ruskin’s description of her, 161 Ruskin falls in love with, and proposes to her, 161-3

Labour movement, 157, 242-6

Ruskin’s absence from modern parliamentary Labour party, 243-6

Ruskin’s influence on first MPs, 27, 153 Lake District, 40, 45, 127, 129, 146, 201-7 special currency, featuring Ruskin, 228 World Heritage Site, 129

Lakeland Arts movement, 204-7, see also Arts and Crafts

Lancaster University, 28, 29, 93, 169 Ruskin Library, 93 land ownership, Ruskin’s practical lessons on, 129-30, 203-4

Landscape and Memory (Simon Schama), 123 landscape and nature, 117-48 Langdale Linen, 204 Larkin, Philip, 40 Laws of Fesole, The (John Ruskin), 62

Laxey (Isle of Man), 204, 205, 217, 229

Layard, Austen, 256 leadership ethical, 32-3, 223, 226 wise, 169

Leigh, Mike, 69

Leighton, Frederic, 18

Leopold, Prince, 22

Letchworth (Garden City), 136-8

Letchworth Garden City Heritage Foundation, 137

Liddell, Alice, 56

Liddell, Henry, 56, 249

Linton, W. J., 202

Little Manatee River (Florida), 261, 276

Lockhart, Charlotte, 87

Long, William, 206

Los Angeles, 44, 144-5

Louise, Princess, 21

Lucca, 82, 83, 230

Lutyens, Mary, 89, 90

MacAdams, Louis, 145

McCarthy, Julie, 239-41

MacCormac, Richard, 93

McDonnell, John, 243

McGrath, Alister, 47 management, Ruskin’s lack of ability, 224, 251, see also leadership

Manchester, 9, 22, 71, 76, 146, 164, 212, 23941, 262

Ancoats, 240

Ruskin’s hatred of the city, 240

Manchester City Art Gallery, 71

Manchester Metropolitan University, 212

Marriage of Inconvenience (Robert Brownell), 87

Marsh, Bruce, 271

Marx, Karl, 187, 245

Marylebone, 232, 238, 250

Mason, Kate, 42, 44, 77

Matlock, 143, 201

Maurice, Frederick Denison, 157, 181, 187

Meyer, Gabriel, 144, 145, 217

Mill, John Stuart, 152, 191

Millais, John Everett, 20, 61, 70-2, 114-16, 193, 196, 248

Millennium Gallery (Sheffield), see Ruskin collection (Sheffield)

Miller, Arthur ‘Mac’, 267, 270-1

Miller, George McAnelly, 261, 267-8

Millett, Kate, 164

mindfulness, 31, 46-7

Mitchell, David, 263

Modern Painters (John Ruskin), 29, 30, 35, 41, 58, 60, 63, 117, 119, 125, 126, 141, 156, 224 contradictions, 72 description of Turner’s Slavers, 190

Law of Help, 121, 148

Ruskin starts work on ‘pamphlet’, 66-9 work on Volume II, 82-3 work on Volume V, 121, 148, 150, 276

Monet, Claude, 249

Monsal Dale, 126, 146

Mont Blanc, 116, 122

Morley, Edith, 246, 250

Morris, William, 101, 111, 135-6, 157, 171, 185, 202, 206, 212, 220, 242-5, 263 politics compared to Ruskin’s, 187, 189

Mr Turner (film), 69 Muir, John, 124-6

Museum of Natural History (Oxford), 105-7

museums and galleries, 26, 73, 105-7, 132, 146-7, 194, 234-7, 239, 241

National Galleries of Scotland, 60

National Gallery (London), 117

National Gallery of Canada, 60

National Health Service, 27, 242, 263 national parks, 124, 127 National Trust, 19, 22, 27, 125, 146-7, 174, 205, 221, 229, 238, 250, 275

Natural England, 132 nature, see environment

Nature of Gothic, The, see The Stones of Venice

Newdigate Prize, 54, 57 nimbyism, 138, see also cities; urban planning Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket (James Abbott McNeill Whistler), 248 Norton, Charles Eliot, 59, 95, 118, 139, 247, 257

Nutter, Ruth, 235-7, 264

obscurity, universal law of, 63 Octavia affordable housing, 238, see also Hill, Octavia

‘Of Queens’ Gardens’, see Sesame and Lilies

Olander, Kathleen, 256 Order of Release, The (John Everett Millais), 114

Orlando, Sean, 215

O’Shea, James, 105-7, 193

O’Shea, John, 105-6

Oxford, 22, 27, 37, 67-8, 78-80, 90, 105-7, 125, 128, 139, 186, 187, 192, 194-5, 214, 220-2, 255, 269, see also Ashmolean Museum; Christ Church; road-building; Ruskin School of Art

Ruskin’s university assocations: not a natural fit as undergraduate, 54; returns as professor, 197-8; gives up professorship for first time, 249; resumes professorship, 252-4

Palace of Westminster (London), 103

Pall Mall Gazette, The, 105, 200, 230, 254

Palladio, Andrea, 96, 99 Paris, 257

Parker, Barry, 136

Parker, Mike, 272, 273

parliamentary politics, Ruskin’s detestation of, 246

pathetic fallacy, 17, 141

Peace – Burial at Sea (JMW Turner), 66

Peacock, David, 166, 275

Peak District, 126, 127

Peden, Paul, 173

Peep Show (TV sitcom), 263

Perera, Sumi, 75 perfection and imperfection, 180, 215-19

Perry, Grayson, 110

Peterloo Massacre, 240 photography, 30, 45, 46, 76

Pisa, 61, 134, 135 pizza, 99

Poetry of Architecture, The (John Ruskin), 268

Porritt, Jonathon, 142-3, 236

Potter, Beatrix, 129

PowerPoint, Ruskin’s visual aids compared, 158

Praeterita (John Ruskin), 36, 52, 120, 252, 255, 257, 274, 279, 290

Pragmatic Programmer, The (Andy Hunt and Dave Thomas), 218

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 6, 22, 27, 60, 61, 65, 70-3, 114, 143, 181, 186-7, 193

Ruskin’s defence of, 71, 152, 155, 199, 248, 266

Young British Artists compared, 70

‘Pre-Raphaelitism’, lecture (1853, John Ruskin), 71, 73

‘Pre-Raphaelitism’, pamphlet (1851, John Ruskin), 71-72, 175, 211, 235

Primavera (Sandro Botticelli), 196, 230

Proust, Marcel, 23

provenance, 31, 109, 214, 216-17

pubic hair, 166, see also Ruskin, John: marriage to Effie Gray

Pugin, Augustus, 102-3, 110, 246

Pullman, Philip, 214 purpose in business, 28, 100-1, 131, 175, see also work, meaning of

Queenswood School, 166

Quercia, Jacopo della, 82

Quill, Sarah, 98

railways, 21

Ruskin’s opposition to, 19, 36, 49, 98, 104, 128

Ramzan, Mohammed, 170, 171

Randal, Frank, 75

Raphael, 72, 84

Rawnsley, Edith, 205

Rawnsley, Hardwicke, 19, 22, 146, 147, 205, 221

Redentore (Venice), Church of, 96, 99 restoration, 84, 92, 97-8, 103, 177, 189

Reynolds, Fiona, 148

Rhodes, Cecil, inspired by Ruskin, 194

Ricardo, David, 152

Richardson, Mary, 53

road-building, Ruskin’s experiment, 222, 231-2, 237

robots and robotics, see automation

Rochdale, 134

Roehampton, University of, 166

Rogers, Samuel, 51, 95

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel, 70, 157

Royal Academy (London), 70, 122, 152, 158, 197

Royal College of Art, 77

Royal Institute of British Architects, 123

Roycroft, 208

RUSKIN (bags), 208, 210, 217

Ruskin (Florida), 259-62, 267-73

Ruskin Art Club (Los Angeles), 7, 144-5, 217

Ruskin Centre for Art Appreciation (Venice), 171

Ruskin collection (Sheffield), 23, 43, 147, 176, 177, 234, 237, see also Guild of St George; Sheffield Ruskin College (Florida), 269

Ruskin College (Missouri), 269

Ruskin College (Oxford), 27, 269

Ruskin Design, 210, 211, 213, 214

Ruskin Hall, see Ruskin College (Oxford)

Ruskin House, see John Lewis Partnership Ruskinite settlements and communities, see also Ruskin Land

Barmouth, 250

Cloughton (Scarborough), 250

Florida, 259-62, 267-73

Georgia, 262

Illinois, 261

Liverpool, 250

Missouri, 261, 269 Tennessee, 23, 268

Wavertree (Liverpool), 250

Ruskin-in-Sheffield, 235, see also Guild of St George; Ruskin collection (Sheffield)

RUSKIN, JOHN

(for works, see separate entries by title of book or lecture)

beliefs, health and personality appearance and personality, 18, 37, 48, 55, 118, 129, 139, 198, 203, 253, 254, 256 contradictions, 14, 71-2, 263 dark side, 30-1, 189-95, 267, see also colonialism and imperialism, Indian art frustration at inability to finish, 63, 97, 273-6 frustration with endless research, 14, 276 mental health, 14, 19, 21, 47, 55, 86, 130, 139, 140, 141, 197, 201, 230, 250-7, 274 motto ‘To-day’, 17, 25-6, 47 opium dependency, 249 physical health, 55, 56-7, 82, 86, 122, 123, 201 politics, 30, 188, 189, 190, 223, 275; modern misconceptions, 270; Ruskin’s suspicion of universal suffrage, 246 religious beliefs, 39, 67, 72, 102, 162, 266; ‘unconversion’, 120-1 sexuality, 91-2

slavery, opinion on, or bias about, 190 travelling style and speed, 31, 49-51, 57, 98, 128; Ruskin’s ‘old road’ through Europe, 50-1

visual sense, 30, 38, 44, 50-2; appreciation of colour, 36-7; precautions against losing his sharpsightedness, 37

personal life birth, 38 childhood, 39-41 death, 17 funeral and burial, 17-19 marriage to Effie Gray, 86-92, 111-16; annulment, 115, 196; ‘incurable impotency’, 20; possible reasons for non-consummation, 90; pubic hair myth, 90 personal wealth, 20, 62, 224 relationship with Rose La Touche, 118, 161-3, 165, 195-7, 229-31 scandals, 20, 114, 116, 256 unrequited early love for Adèle-Clotilde Domecq, 14, 54-5, 88, 118

reputation and influence aphorisms misattributed to Ruskin, 28, 210-11 awkward role model, 266

RUSKIN, JOHN, reputation and influence (cont.)

blogger, television host, 198 celebrity, 19-21, 118, 160 hard to categorise, 30 Instagrammer, 30 lasting influence summarised, 23, 24 landmarks named after Ruskin, 23, 35, 36 likely attitude to Versace, Prada etc, 96 merchandise and brand, 21, 22, 210 one-man worldwide web, 33, 73 reputation after his death, 25, 48, 116, 266, 267

twentieth century policies Ruskin influenced, 267 why he is needed today, 26, 31-4, 273-6

work and career architecture, ‘hero of’, 94 ‘art attacks’, 82; Carpaccio, 196, 227, 230; Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (Paolo Veronese), 120; Tintoretto, 83; tomb of Ilaria del Carretto (Jacopo della Quercia), 82, 230 art critic, 65-73 artist, 60-4 critic of laissez-faire economics, 151-4 champion of the Pre-Raphaelites, 71, 152, 155, 199, 248, 266 champion of Turner, 65- 72 defamer of Whistler, 247-9 draughtsman, 56, 57, 60-4, 264 environmentalist, 27, 32, 139-44, 146-8, 212, 229 geologist, 41, 105, 124, 126 land-owner, 129-30, 203-4 manager, lack of ability as, 221, 224, 251 mountain-lover, 121-5 philanthropist, 226-9, 234, 238 photography, interest in, 30, 46 poet, 40-1, 52, 54, 57 polemicist, 29, 71, 154, 190, 198 professor, 194, 197-8, 247, 254 prose stylist, 71, 74, 85, 128, 190, 219-20, 246, 266; claims to greatness, 257-8; exhilarating rudeness, 29; hard to read but rewarding, 28-9; lauded by Proust and Tolstoy, 23 public speaker, 29-30, 139-42, 159, 253, 254 student, 53-4, 55-7, 67 teacher, 41, 75, 157-60, 197-8 work habits, 28, 46, 61, 94, 95, 155-6, 247, 274

Ruskin, John James, 38, 53, 56, 87, 155 art investor, 68, 112 death, 189 epitaph, 190

financial legacy, 20, 224, 226 helicopter parent, 40 taste for art and literature, 39 traveller, 49-50

Ruskin Lace, 204, 213

Ruskin Land, 130-4

‘Ruskin Oak’, 131, 133, 213

Ruskin Library, see Lancaster University

Ruskin loaf, 236

Ruskin, Margaret (née Cock), 36, 38, 53, 155, 201 helicopter parent, 40 influence on Ruskin’s beliefs, 39, 120

Ruskin Mill Trust, 171-2

Ruskin Museum (Walkley), see Ruskin collection (Sheffield)

Ruskin pants, 23

Ruskin Park (Denmark Hill), 23, 35, 36

Ruskin School of Art (Oxford), 27, 78-80, 195, 197, 252 changes name from Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art, 78

Ruskin School of Drawing, see Ruskin School of Art (Oxford)

Ruskin societies, 22

Ruskin Today (Kenneth Clark), 265

Ruskin Union, 22

Ruskin’s Bitter, 211-12

Ruskin’s Venice: The Stones Revisited (Sarah Quill), 98

Rydings, Egbert, 204, 229

St Albans, 102

St Andrew’s Church (Coniston), 17

St George and the Dragon (Vittore Carpaccio), 227-8, 230

St George’s Fund, see Guild of St George

St George’s Museum (Sheffield), see Ruskin collection (Sheffield)

St Mark’s Rest (John Ruskin), 155, 259

St Pancras Station, 103

San Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Scuola di (Venice), 227

San Giorgio Maggiore (Venice), 96, 99

San Marco, Basilica (Venice), 85, 92, 98, 177, 256

San Marco, Piazza (Venice), 85, 95, 96

San Moisè, Church of (Venice), 96, 104

San Rocco, Scuola di (Venice), 26, 83

Saussure, Horace-Bénédict de, 44

Scarpa, Carlo, 103 Schaffhausen, 51-2

Schama, Simon, 123 science, see geology Scott, George Gilbert, 103 Scott, M. H. Baillie, 207

Scott, Walter, 39, 87, 88, 158, 187, 200, 273

Seaside (Florida), 137 seeing, 31, 35-52

‘vidi’ as Ruskin’s credo, 47

Sesame and Lilies (John Ruskin), 136, 165, 177, 240

‘Of Queens’ Gardens’, 163-5; contrasting 19th and 20th century reactions, 166

Seurat, Georges, 249

Seven Lamps of Architecture, The (John Ruskin), 38, 81, 82, 101, 104, 110, 117, 148, 156, 218

Severn, Arthur, 201, 226, 255

Severn, Joan, 28, 48, 201, 226, 231, 251-2, 256-8, 274

Ruskin’s ‘baby-talk’ letters to her, 254-5

Sexual Politics (Kate Millett), 164 Shadow of Death, The (William Holman Hunt), 71

Shaw, George Bernard, 245

Sheffield, 22, 23, 43, 50, 176, 177, 232, 234-7, 239, 252, see also Ruskin collection (Sheffield)

Siena, 257

Sierra Club, 125 Simon, John, 247, 248 Simplon Pass, 46 Simpson, Arthur, 206 Sinden, Neil, 133

Slade Professor of Fine Art, Ruskin as, 194, 197-8, 247, 254

Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying – Typhoon Coming On (Joseph William Mallord Turner), 190 Smith, Adam, 152 Smith, Chris, 244 Snapchat, 44 social inequality, 27, 150, 226, 243 social mobility, Ruskin no fan of, 168 socialism, 187-9, see also Labour movement; Christian Socialism Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, 135, 189 software, 9, 131, 218-19

South County (film), 270 Spiegel, Evan, 44

spiritualism, 269

Ruskin’s interest in, 231

steampunk, 214-15

Steampunk Bible, The (Jeff VanderMeer and S. J. Chambers) 214

Steiner, Rudolf, 171

Sternfeld, Joel, 144

Stickley, Gustav, 207, 261

Stones of Venice, The (John Ruskin), 29, 47, 82, 84-5, 96, 98, 100-2, 111, 113, 126, 168, 218

‘The Nature of Gothic’, 101, 113, 156-7, 186-9, 205, 214-15, 219, 243

Study of Gneiss Rock (John Ruskin), 61

Sukatorn, Robin, 75, 76, 77, 79

Sullivan, Louis, 108

Swan, Henry, 176, 234, 235

Tate Britain (London), 69, 119 technology, see automation; software

Telford, Henry, 38, 51

Tennyson, Alfred, 19, 68, 191

Thackeray, William Makepeace, 151, 274

Thirlmere, 146

Time and Tide (John Ruskin), 168, 169, 199, 214

Timorous Beasties, 212

Tintoretto, Jacopo, 72, 83, 84, 96, 173, 253, 261

Tissot, James, 60

‘To-day’, Ruskin’s motto, 17, 25-6, 47

Tolstoy, Leo, 23

tourism, 19, 46, 49-50, 85, 94, 98, 100

Toynbee, Arnold, 221, 222, 237, 238

Toynbee Hall (London), 9, 137, 222, 238, 241, 243, 277

Toyota, 180

‘Traffic’ (lecture, John Ruskin), 224

Trotter, Lilias, 253

Truman Show, The (film), 137 Tunbridge Wells, 236

Turin, 82, 120, 128

Turner, Joseph Mallord William, 18, 27, 29, 51-2, 95, 143, 190, 197, 248, 253, 265 linked by Ruskin to Pre-Raphaelites, 70-2 meets Ruskin, 65-9 myths about his bequest, 119 Ruskin as executor and highly critical cataloguer, 117, 119

Twelves, Marian, 204 Twitter, 28

Two Paths, The (John Ruskin), 158, 185

university settlement movement, 222, 238

Unto This Last (John Ruskin), 19, 28, 136, 143, 165, 169, 178-80, 184, 225, 233, 240, 245, 265, 274

lessons for the modern merchant, 223 marks Ruskin’s shift to social criticism, 150-5 parallels with aftermath of 2008 financial crisis, 153 reaction to and influence of, 27, 153, 242

Unto This Last (workshop), 150, 178-81, 205, 209, 215

Unwin, Raymond, 136 urban planning, 32, see also cities; nimbyism utopian, Ruskin advises against use of the word, 233

VanderMeer, Jeff, 214, 216 Venice, 26-7, 32, 36, 45-7, 50-1, 72, 86, 91, 98, 101, 102, 104, 107, 155-6, 171, 177, 196, 218, 227, 229-30, 256, 261, 276, see also Stones of Venice, The decline of Venetian empire as warning to British Empire, 100 impact of the city on Ruskin, 80-5, 92-7 Ruskin and Effie Gray’s last visit, 111-13 Ruskin’s influence on modern Venice, 97-100

Ruskin’s insights about, 100 Veronese, Paolo, 72, 82, 96, 120 Victoria and Albert Museum (London), 83, 158

Victoria, Queen, 17, 21

Viollet-le-Duc, Eugène, 108 visual literacy, 44, 77 Vrooman, Walter, 269

Waithe, Marcus, 275

Walkley, see Ruskin collection (Sheffield); Sheffield War. The Exile and the Rock Limpet (JMW Turner), 66

Warrell, Ian, 119 Watts, George Frederic, 18 wealth, 20, 62, 152, 154, 184, 190, 223-9, 236-7, 243, see also illth Webb, Robert, 263

Wedderburn, Alexander, 200, 221, 266 welfare state, 27, 237-43, 263, 275 Ruskin as ‘motivator’ for, 242 Welwyn Garden City, 136 West, Thomas, 38, 44

Westmill, 250

Westminster Abbey (London), 17

Whistler, James Abbott McNeill, 20, 145, 187 lawsuit against Ruskin, 247-9

Whitehouse, John Howard, 93, 169, 170, 267

Whitelands College, 166, 252, 275 May Day festival, 166 Wilde, Oscar, 222, 231

Wilkie, David, 66

Wilmer, Clive, 233-5, 241, 242

Winnington Hall (Northwich), 163

WMC, see Working Men’s College (London) Wool Exchange (Bradford), 30, 104, 224

Wordsworth, William, 19, 40, 68, 129 work, 149-60, 177-84

manual labour, 159, 168, 181, 219-22 meaning of, 32, 100-1, 111, 156-8, 175, 179-84, 222, 236, 263

Work (Ford Madox Brown), 71, 181, 182, 239 Work (Hunt Emerson), 183 ‘Work’ (lecture, John Ruskin), 181 ‘Work of Iron, The’ (lecture, John Ruskin), 236 Working Men’s College (London), 73, 101, 157, 159, 166, 187, 197, 234, 240, 242, 272 in 21st century as WMC, 172-6

Wright, Frank Lloyd, 6, 108, 109, 111

Wyre Forest, see Ruskin Land Wyss, Carol, 75

Young British Artists, see under PreRaphaelite Brotherhood Youth of Moses (Sandro Botticelli), 230

Zorzi, Alvise Piero, 98