“He lived in his painting”

Interview with Zsuzsa Hantaï by Anne Baldassari

Anne Baldassari: By way of an introduction to this catalogue of the exhibition marking the centenary of Simon’s birth, could you describe the world in which you lived when you met in 1945, in the aftermath of the Second World War, and your respective backgrounds?

Zsuzsa Hantaï: I was born in 1925, into a provincial bourgeois Jewish family. My father Emil Biró was a lawyer and we lived in a large house in Békéscsaba, 2 a remote rural town in southeastern Hungary, surrounded by countryside. My education was entrusted to an Austrian governess. So I learned German very early. At school we spoke Hungarian. There was an Englishwoman who often came to work for us, and I also spoke English. This is the background that my bourgeois family gave me. In high school I learned Latin—in those days girls did not learn Greek, only Latin. I learned French later, when we were preparing our trip to Paris, at the Alliance Française in Budapest. I left my family very early, at the age of thirteen, to go to a private boarding school in Budapest, where the teachers were highly qualified professors who were banned from teaching at the university because of the new laws discriminating against Jews. They had got together to start a school. In 1943, I graduated from high school and in the fall I passed the entrance exam for the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest and was given a scholarship. I was “the Jewish student” admitted for that year.3 Simon was also from a rural family that came to Bia in the seventeenth century, when the Turks left the country and were replaced by German settlers. His was a Catholic family.

They were honest and hardworking people who taught the Hungarians how to acclimatize grapes, to plant and tend them. Half of the village was German, the other half was Hungarian, and the two communities did not mix. As a child, Simon was deeply marked by the music of Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672), whose psalms and oratorios he used to sing at Easter, but not knowing that he was a famous German composer. He studied at a scientific high school, a very good institution that trained engineers, the Ferenc Toldy High School in Budapest. He was the only villager in his class. Then, contrary to his family’s expectations, he entered the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts in 1941.

AB: Under what circumstances did you meet Simon? Did you attend the same classes, share the same interests?

ZH: I didn’t meet Simon until after the war.4 He was three years older than me and was finishing his studies when I entered the academy. At the end of his studies, he had been the assistant—he prepared the still-life arrangements that the students had to paint—of the watercolor teacher Elekfy Jenő,5 and this allowed him to survive, to have lunch every day at the school, and to have access to the ateliers and the library. His cohort included the future great artist Judit Reigl, Poldi Lipót Böhm, Antal Biró, and Sándor Zugor.6 With them he discovered the monumental paintings of the Hungarian expressionist painter Tivadar Kosztka Csontváry,7 founding figure of Hungarian modern art. He was called the Hungarian Henri

18

“Without Zsuzsa, I would never have left Hungary, and all the rest.” S.H.1

19

Pierre Faucheux, Zsuzsa, Simon, and Daniel Hantaï, Saint-Malo, 1953

228 Meun, Meun, 1968. Acrylic on canvas, 230 × 205 cm. MAMAC collection, Nice

229

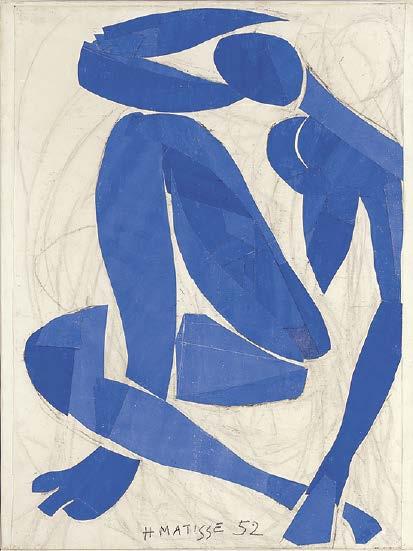

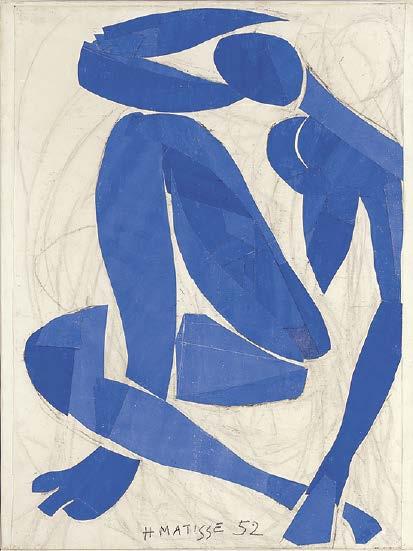

Henri Matisse (1869–1954), Nu bleu IV (Blue nude IV), Nice, 1952. Charcoal and gouache on paper, cut and glued on paper and mounted on canvas, 103 × 74 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris, on deposit at the Musée Matisse, Nice

Tabula

262

, Paris, 1980. Acrylic on canvas, 262 × 458 cm. Private collection

263

Sans titre (Untitled), Paris, 1985.

Acrylic on canvas, 292 × 490 cm.

Private collection

304

305

A Story of a Life: Simon Hantaï, 1922–2008

Anne Baldassari

1922: Bia

Simon Handl was born on December 7, 1922, in Bia (now Biatorbágy), a rural town close to Budapest. His parents belonged to a small farming community of German origin, which emigrated to Hungary in the seventeenth century. In 1939, his family, of Swabian Catholic heritage, changed their name to Hantaï, to sound more Hungarian. As a child, because of complications from a severe bout of diphtheria, he lost his sight for several months. This extreme experience of sensory deprivation would have a strong impact on his life and his work.

1932–1940: Simon Hantaï completed his secondary-school studies at the Toldy Ferenc Gimnázium in Budapest. He and his brother were the only pupils from a rural area in this school generally reserved for the children of the urban middle classes. He was already interested in art and, from sixth grade onward, took optional sculpture classes. His notebooks, particularly his natural sciences note books, show an innate talent for drawing. He was a brilliant and hardworking student. Later, he wrote: “Childhood: I’m going to be a painter (not me-too / hasn’t seen any paintings)” (Simon Hantaï, undated manuscript, given to the author in 1991–1992).

1941–1945: Budapest

1941–1943: Contrary to the expectations of his father, who hoped to see him and his brother pursuing careers as engineers, he took the entrance exam for the Budapest Academy of Fine Arts, which admitted him in 1941, aged nineteen. Due to his family’s financial situation, he had to pay his own way during his studies. He threw himself into campus life and soon became a student representative and spokesman, as well as a teaching assistant. He exhibited regularly with his classmates at events organized by the Academy of Fine Arts.

In March 1944, the Kingdom of Hungary, which had joined the Rome-BerlinTokyo axis in the 1930s, was invaded by its German ally. Hantaï, in a speech given as the academy’s student president, spoke out publicly against Nazi Germany and the pro-Nazi Hungarian government. He was jailed by the police but managed to escape. His mother hid him for several months in Bia, until the arrival of the Red Army, which occupied the region. He was then taken on as a cowman by the troop as they advanced toward Budapest on the eve of the siege. He was able to run off and returned to the capital on foot.

After the liberation of Budapest and the brief period of euphoria surrounding the proclamation of the new Hungarian Republic (1945–1948), art and culture flour ished. In April 1945, Hantaï returned to the Academy of Fine Arts, which had just reopened. He helped to repair the bombed buildings, and to rescue, restore, and exhibit major works by the Hungarian expressionist painter Tivadar Kosztka Csontváry (1853–1919) at the academy. Hantaï’s Peinture (L’Arbre des lettrés) (oil on canvas, 117 × 161 cm, MNAM, Paris), produced in 1950–1951, is a direct reference to Csontváry’s masterpiece, Pilgrimage to the Cedars of Lebanon (1907, oil on

94

Portrait of Simon Hantaï aged ten, Bia, Hungary, 1932

Portrait of Simon Hantaï at the age of fifteen, Budapest, 1937

canvas, 205 × 200 cm, Hungarian National Gallery). He was employed in various educational and administrative jobs, including as assistant to the professor of watercolor Jenö Elekfy (1895–1963). He took great interest in the activities of the “European School” cultural circle, created in March 1945. Between September 1945 and May 1946, Hantaï attended the history of art classes given by François Gachot, director of the Alliance Française. They became friends. Gachot intro duced him to the works of Henri Matisse and Pierre Bonnard, allowed him to use his personal library, and taught him basic French. Hantaï curated the Christmas exhibition of the Youth Circle of the Academy of Fine Arts, where he exhibited several works, including large watercolors. There he met Zsuzsa Biró, an art stu dent three years his junior, whom he married on January 31, 1947.

In 1945, the magazine Színhá published a feature on prizewinners from the Academy of Fine Arts, including profiles of the young couple. Zsuzsa, aged twenty, had escaped from the concentration camps where almost 500,000 Hungarian Jews were exterminated in a period of a few months, between March and December 1944. She was saved by her professor at the academy, István Szönyi, who, together with his family, was later recognized as “Righteous Among the Nations” by the International Institute for Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center (on October 2, 1984). Her words express her deep feelings of powerlessness and strangeness vis-à-vis the world: “For me, life is a state in where beings act without a specific role. This vibrant and sometimes hazy state is what I most like to express. Consequently, a certain playful dimension dominates my images.” Hantaï’s comments are more structured, and show him as a politi cally committed student, used to public speaking: “The process of decomposition that has led humanity to the current destruction has been reflected in art as total destruction. This phenomenon of demolition has reached its peak. … Art is now progressing in a new direction: not destruction, but the birth of a golden age. Picasso has already started this movement with certain of his paintings. Building this new era is very difficult, especially when we ask the question: has the next Giotto or Masaccio of our time already been born?” (Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris).

On October 6, 1946, as a left-wing Marxist carried along by the reforming zeal that affected all progressive Hungarian young people at the time, Hantaï joined the Hungarian Communist Party. He tried, unsuccessfully, to persuade Georg Lukács to back the establishment of a program to support the visual arts.

PHOTOGRAPHIC CREDITS COPYRIGHT

Archives Anne Baldassari: pp. 2, 9, 16, 42, 47, 53, 56, 67, 71, 75, 79, 83

Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: pp. 3, 7, 11, 21, 49, 94, 95, 100 (b), 101 (b), 102 (t and c), 103 (t), 104, 105, 108, 109, 111, 112–113, 115, 118, 120, 121, 122, 123, 125, 129 (b)

© Muriel Anssens – City of Nice: p. 228

© Robert Bayer: p. 224

Photo Jean-Marie Blanc / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 91

Photo Édouard Boubat / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: pp. 41, 125, 127, 129 (t), 193, 205, 221, 233, 245, 259, 287, 301, 329, 339, 353

Photo Brassaï / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 141

Association Atelier André Breton: 102 (b)

Photo Archives Daniel Buren: pp. 35, 37

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-CCI, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Philippe Migeat: p. 173

© Centre Pompidou, Mnam-CCI, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Adam Rsepka: pp. 167, 169

Photo © Centre Pompidou, Mnam-CCI, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image from the Bibliothèque Kandinsky: p. 98

Photo Jacques Cordonnier/Association Atelier André Breton: p. 100 (t)

© Gyorgy Darabos: p. 170

Éclair-Mondial photo agency / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 101 (t)

Digital Photo Etsy: p. 103 (b)

Photo Pierre Faucheux / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 19

Photo © Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes: pp. 10, 142, 144–145, 146, 148, 149, 150, 151, 168, 176–177, 184, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201, 206, 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217, 222, 223, 226, 227, 234–235, 237, 238, 239, 241, 246, 247, 248, 249, 250, 251, 252, 253, 254, 255, 260-261, 262–263, 264, 265, 266–267, 268–269, 270, 271, 272-273, 274–275, 276, 277, 280, 281, 282–283, 288, 289, 290, 291, 293, 294, 295, 303, 304–305, 306, 307, 308, 309, 310, 311, 312, 313, 314, 315, 316, 317, 318, 319, 320, 321, 322, 323, 324, 325, 328-329, 332, 333, 340–341, 344–345, 346, 347

© Fondation Louis Vuitton / Béatrice Hatala: pp. 143, 157, 158–159, 161

© Fondation Louis Vuitton / Philippe Migeat: pp. 88–89, 138–139, 152–153, 162–163, 180–181, 190–191, 202–203, 218–219, 230-231, 242–243, 256–257, 284–285, 298–299, 326–327, 336–337, 348–349

Courtesy Galerie Jean Fournier, photo © Fondation Louis Vuitton / David Bordes: p. 147

Courtesy Galerie Jean Fournier, photo © A. Ricci: p. 225

Courtesy Gagosian: pp. 292, 296, 297

Photo © Vagn Hansen / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 155

Photo Daniel Hantaï / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: pp. 29, 37, 93, 126, 135, 183

Photo Simon Hantaï / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: pp. 136–137

Photo Jacqueline Hyde / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 129 (b), 131

© Laurent Lecat: pp. 178, 179, 185

© Philippe Migeat: pp. 166, 171, 342–343

© Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole –

Photograph Frédéric Jaulmes: p. 175

Courtesy Musée Matisse, Nice, photo: © François Fernandez: p. 229

© 2013. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence: p. 96

Photo Hans Namuth / Courtesy Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona: pp. 97, 99

© Paris Musées, Musée d’Art Moderne, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image City of Paris © Primae / David Bordes: p. 186

© Primae / Louis Bourjac: pp. 187, 189, 236, 278–279, 302

Photo Madeleine Saura-Augot / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 23

Photo Antonio Semeraro / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: endpapers: pp. 72–73, 133

Photo Étienne Sved / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: pp. 63, 107, 108 (l), 117, 165

Photo Agnès Varda / Archives Simon Hantaï, Paris: p. 25

© Archives Simon Hantaï / ADAGP, Paris, 2022

© Jean-Marie Blanc

© Édouard Boubat, 2022

© Estate Brassaï

© DB – ADAGP, Paris, 2022, for the work of Daniel Buren

© Pierre Faucheux

© Vagn Hansen, 2022

© Daniel Hantaï

© Jacqueline Hyde, Courtesy Centre Pompidou / Bibliothèque Kandinsky

© Succession H. Matisse for the work of the artist

© 1991, Hans Namuth Estate, Courtesy Center for Creative Photography

© Jackson Pollock / ADAGP, Paris, 2022

© Madeleine Saura-Augot

© Antonio Semeraro, 2022

© Étienne Sved, 2022

© Agnès Varda

The section openings of the catalogue are an original creation by Anna Radecka and Julien Boulard for c-album, based on pages from undated manuscripts that Simon Hantaï wrote or collected together between November 1991 and January 1992, Archives Anne Baldassari. All rights reserved.

The scans of Simon Hantaï’s original manuscripts were made by Rémy Saglier for the Fondation Louis Vuitton.

© Éditions Gallimard, Paris, 2022 www.gallimard.fr

© Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, 2022 www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr

Photoengraving: Litho Art New, Turin ISBN: 978-2-07-297989-7 This publication was printed in April 2022 on the presses of Stamperia Artistica Nazionale, Trofarello Printed in Italy

Legal deposit: May 2022 434 089

368