Opposite: detail of no. 85

Below: fig. 8 Display of fruit, retaining the label from the 1685/86 inventory. South German, lead with gilding, c.1600–40. Diameter 6.4 cm. Given by Elias Ashmole in 1683. Ashmolean (WA 1908.47).

Opposite: detail of no. 85

Below: fig. 8 Display of fruit, retaining the label from the 1685/86 inventory. South German, lead with gilding, c.1600–40. Diameter 6.4 cm. Given by Elias Ashmole in 1683. Ashmolean (WA 1908.47).

The Ashmolean Museum is famous as the oldest public museum in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1683 with Elias Ashmole’s gift of his collections, at the core of which was the celebrated cabinet of curiosities assembled by the Tradescant family in the first decades of the seventeenth century and displayed for many years in Lambeth in London. The Tradescants’ collection was a good example of the encyclopaedic but eclectic ‘Wunderkammer’, a type of treasure house of miscellaneous objects of every type and culture, that became so popular among elites in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The Tradescants did not, as far as we know, own any significant bronze statuettes or utensils. However, early inventories of the Ashmolean Museum drawn up in 1685 and 1695 list 51 objects recognisable as the small metal reliefs known as plaquettes, all but a couple of which survive today in the Museum’s collections (e.g. no. 70). Most, if not all, were probably collected by John Tradescant the Elder in the early 1600s, since they are almost certainly the ‘Divers medalls cast of in severall metalls’ referred to in the 1656 printed catalogue of the Tradescant collection.5 This makes them the earliest documented major collection of plaquettes anywhere. The great majority are not Italian, but German or Dutch, whilst they are mostly made from lead rather than bronze, with some retaining their fine original gilding (fig. 8).

Much of Elias Ashmole’s collection, including the plaquettes, ended up in the Bodleian Library, where over time they were joined by other plaquettes and medals, many coming from the collections bequeathed to the University by the bibliophile Richard Rawlinson in 1755.

As a young man Rawlinson spent six years living in Italy. In Rome in 1721 he purchased a collection of 700 seals, including the rare seal matrix of Cardinal Scipione Rebiba (no. 29). Rawlinson’s bequest also included the remarkable Jewish artefact known as the Bodleian Bowl (no. 2).

In the later nineteenth century and first decades of the twentieth century, many of the objects accumulated over the course of the centuries by the Bodleian, including the Romanesque prophets (no. 1) and a few other more minor bronzes, were transferred to the Ashmolean Museum.

Very few early bronze sculptures were acquired by the Ashmolean during the nineteenth century, with the notable exception of two of the Museum’s most important bronze sculptures. Firstly, Daniele da Volterra’s moving portrait of his master and friend Michelangelo Buonarroti (no. 50),

The Bodleian Bowl

France, c.1240–1260

Bronze. 25.1 cm high; 24.4 cm diameter

Discovered c.1696 in a moat in Norfolk; Dr. John Covell, Cambridge; acquired in 1722 by Edward Harley, 1st Earl of Oxford; Oxford sale, 3rd day, 10 March 1742, Bronzes, Antiquities etc, lot 17, bought by Richard Rawlinson; bequeathed in 1755; Bodleian Collection; transferred from the Bodleian Library, 2006 AN2009.10

This beautifully-made and perfectlyproportioned two-handled vessel is a masterpiece of modelling and casting. Under each handle is a fleur-de-lis, suggesting a French origin, whilst around the centre of its body runs the Hebrew inscription which has secured the Bodleian Bowl’s fame as a rare and significant document for the once-flourishing Jewish communities of Medieval England and France. The vessel is supported on three feet in the approximate form of animal hooves, above each of which is a vivid pictogram in relief depicting, respectively, a bird, an antlered deer and a chrysanthemum-like symbol.

After its discovery in around 1696, the Bodleian Bowl passed through the hands of a series of antiquarian owners before being bequeathed to the University by the bibliophile Richard Rawlinson (1690–1755), as ‘my metal Jewish vessel’. In the Bodleian Library, the vessel was valued above all for its inscription, originally being catalogued as a manuscript. There has been much debate around the precise wording and meaning of the inscription, the most widely accepted translation of which is: ‘This is the gift of Joseph, son of the Holy Rabbi Yechiel, may the memory of the righteous holy one be for a blessing, who answered and asked the congregation as he desired, in order to behold the face of Ariel [i.e. Jerusalem] as it is written in the Law of Jekethiel [i.e. Moses], “And righteousness delivers from death”.’

The inscription connects the bowl with two prominent members of the Jewish communities

in France and England in the thirteenth century: the famous Parisian Talmudic scholar Rabbi Yechiel of Paris (active 1225, died c.1268) and his eldest son Joseph, who was a leading rabbi in Colchester, where he also went by the delightful name of Messire Delicieux. We know that Joseph and his father planned to move to Palestine, and that Joseph at least reached there in around 1260. One interpretation of the inscription suggests that the vessel may have been a container for collecting charitable donations, perhaps to fund Joseph’s journey to Palestine.

By the thirteenth century there were flourishing small Jewish communities in many towns and cities in England and France. In the course of the century, however, these groups suffered from increasing persecution and violence, culminating in England in Edward I’s expulsion in 1290 of the entire Jewish population. Persecution was probably the reason why, like many other English Jews, Joseph decided to make his way to Palestine. Presumably he left the vessel behind in England. Perhaps a subsequent owner hid or lost the Bodleian Bowl in the frantic rush to escape the country after the king’s edict in 1290. Although we will never know how it ended up in a moat, this fine vessel, with its mysterious inscription, is a poignant reminder of the once-flourishing Jewish communities in Colchester, Oxford and other medieval English cities, as well as the sufferings they endured.

Figure of the god Apollo

Italy, Mantua, c.1470–1500

Bronze. 11 cm high

Bought by C D E Fortnum in Florence in 1857; bequeathed in 1899.

WA1899.CDEF.B414

This small and graceful figure of a youth with a drapery thrown casually over his left shoulder is a depiction of Apollo, god of the sun, usually portrayed during the Renaissance as a handsome, slightly effeminate young man. The fluently modelled figure encompasses the Renaissance image of the god. He probably originally held an arrow or a bow in his outstretched right hand, referring to stories of Apollo the hunter – notably his slaying of the serpent-like creature Python. Apollo and his sister Diana also used their bows and arrows to kill the children of Niobe, after she had insulted their mother Latona (see no. 65). Fortnum mounted the figure on a small triangular pedestal embellished with bacchic dancing figures, which also dates from around 1500. In its small size the statuette is comparable to many Roman bronze figurines, objects that were eagerly sought after by collectors at this time. This relationship to Roman prototypes is even clearer in a more sharply modelled version in the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris. The Ashmolean’s statuette was probably made in the latter decades of the fifteenth century in northern Italy, perhaps in Mantua, where the painter Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506) settled and spent most of his life. Mantegna may in fact

have known or even owned a version of this very model. On the death of his second son Ludovico in 1510, just a few years after his father, an inventory was made of Ludovico’s belongings in the family house just outside Mantua. Many items inherited from Andrea were listed in the inventory, including just a single bronze. Kept with other objects in a walnut chest, it was described as ‘a small figure in bronze with an arrow in its right hand and a drapery over the other arm’.

Andrea Mantegna was not only the most influential painter working in northern Italy in the second half of the fifteenth century, but he also played an important part in nurturing appreciation and knowledge of the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome. In 1472, before setting off for the baths, Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga (1444–83) wrote to his father, Ludovico III, Marquis of Mantua and Mantegna’s employer, to ask permission for his court painter to join him in order to see ‘my cameos and bronze figurines and other beautiful antique things, which we will study and discuss between ourselves’. It is easy to imagine Andrea and Francesco sitting at the baths, passing little bronzes like the Ashmolean’s Apollo to and fro, whilst eagerly debating their merits.

Vincenzo Grandi (c.1480/90?–1577/78) and Gian Girolamo Grandi (1508–60)

Italy, Padua, c.1540–50

Bronze, gilt. 19 cm high, 24.2 cm long, 13.7 cm wide

Fernand Adda (1890–1965); Adda sale, Collection d’un grand amateur, Palais Galliera, Paris, 29 November–3 December 1965, lot 381; Daniel Katz, by whom lent to the Ashmolean Museum, 2002–16; given by Daniel Katz Ltd in 2016 through the Cultural Gifts Scheme, in honour of Jeremy Warren’s Catalogue of Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture in the Ashmolean Museum WA2016.40

In 2016, the Ashmolean was lucky to acquire a second masterly work in bronze made in the workshop of Vincenzo and Gian Girolamo Grandi. This writing casket is an elegant and practical object – its solid base and low centre of gravity ensuring excellent stability. Inside is space for an inkwell that is now missing, but the sand pot used for drying wet ink survives, whilst there are also compartments for quill pens. The heavy lid can be easily and safely lifted using the remarkable figure of a half-length armless satyr, which rises from the centre and resembles a small seal figure (see no. 21(d)). The distinctive, sharply defined decorative ornamentation is as varied and inventive as that on the candlestick from the Grandi workshop. It includes acanthus leaf, scale and wreath ornament, swelling leaves and, along all four sides, a frieze of cow skulls (bucrania) connected by swags, and with ribbons attached to the horns. At the centre of each side of the cover is a shield with an unidentified coat-of-arms.

The writing casket was probably made in Padua during the 1540s, by which time Vincenzo and Gian Girolamo Grandi had returned from Trent. But they evidently maintained important contacts with Trent; the inkstand

can be linked with the single document known to survive in Vincenzo Grandi’s hand, a letter written in 1546 to Bernardo Cles’s successor as Prince Bishop of Trent, Cardinal Cristoforo Madruzzo (1512–78). The letter accompanied an inkstand, which is now lost, but was described in great detail by Vincenzo and must have been very similar to the Ashmolean’s casket, elements such as the bucrania and the swags all but identical. Vincenzo wrote in glowing terms of this inkstand as ‘the instrument which assists high minds when they are writing noble matters worthy of remembrance, winning for themselves perpetual fame and immortal glory through the exercise of their genius, dedicating their name to the Temple of Glory’. He went on to suggest the meaning of the bucrania and the swags: ‘[the] dry ox skulls signify the labour on which glory depends, whilst those swags suspended from them demonstrate nothing less than the triumph of virtue and the honour of glory’. Making allowance for some exaggeration on the part of the artist, this unique letter shows how bronze utensils and their decorative elements could sometimes be made to carry their own meanings and dignity.

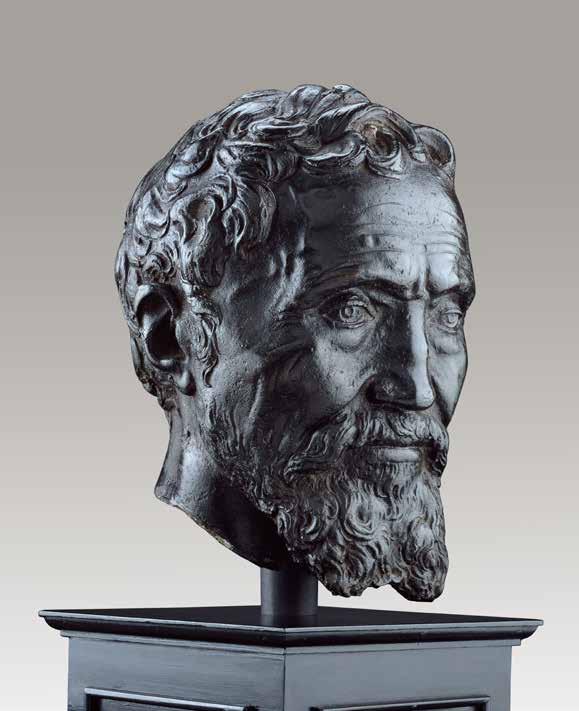

Portrait head of Michelangelo Buonarroti

Daniele da Volterra (Daniele Ricciarelli, c.1509–1566)

Italy, Rome, c.1564–66. Bronze. 28 cm high

Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830); Lawrence sale, Christie’s, 17–19 June 1830, lot 392, bought by Samuel Woodburn (1783–1853); given in 1845 by William Woodburn. WA1846.307

This magnificent likeness of Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564) in old age is one of the most sympathetic and perceptive sculpted portraits ever produced. The great sculptor and painter, regarded as a titanic genius already in his own lifetime, is shown as a noble figure immersed in thought, carrying the weight of his years. The portrait faithfully reproduces the broken nose that Michelangelo received as a young man in a scrap with Pietro Torrigiani (1472–1528), who left Florence to seek his fortune in the less competitive environment of early Tudor England. The portrait is wonderfully fresh and vigorous, preserving in bronze all the appearance of the original wax model.

Daniele da Volterra (c.1509–66), a former pupil and close friend, was present at Michelangelo’s death in Rome on 18 February 1564. Their friendship accounts for the intensely lifelike quality of the portrait which, as the flattened ears indicate, is based on a mask – a plaster cast taken from a person’s face. ‘Death masks’ were often made when a person died, but this portrait is almost certainly based on a ‘life mask’, taken when the subject was living. It clearly also does not show Michelangelo in extreme old age; comparison with other surviving likenesses would indicate that the portrait probably dates from the 1550s, when he was in his seventies.

It is generally thought however that Daniele da Volterra only began to make bronze casts from his model of Michelangelo after his friend’s death, in response to widespread demand for images of the late artist. At the time of Daniele’s own death just two years later in 1566, the inventory of his household goods listed six bronze casts of Michelangelo’s head – three of the head alone, and another three attached to a bust of some sort. No other Renaissance portrait sculpture is today recorded in so many versions, with ten casts surviving in European museums. Charles Fortnum published two pioneering articles on the portraits of Michelangelo, one of them devoted to a study of the eight versions of the bronze heads that he knew about. In 2022, nine of the ten surviving casts were exhibited together in Florence, when scientific tests were undertaken to try and work out which of the surviving casts were likely to be Daniele’s primary versions. Although no definitive conclusions could be drawn, the exercise resulted in general agreement that the quality of the Ashmolean’s head marked it out as one of the finest. It was once owned by Sir Thomas Lawrence, whose collections also included incomparable series of drawings by Michelangelo and Raphael. Most of these were sold to the University in 1846 by the dealer Samuel Woodburn, at around the same time that his brother William presented the bronze head.

All images Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, with the exception of the following:

p.12 © The Elisabeth Frink Estate and Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2023.

p.12 Ian Littlewood / Alamy Stock Photo

p.17 Mondadori Portfolio/Electa / Bridgeman Images

p.18 Bridgeman Images

pp. 75–77 Courtesy Sam Fogg Ltd

p.83 © Wallace Collection / Bridgeman Images

p.88 © The Trustees of the British Museum

p.116 Private collection

p.134 The Walters Art Museum

p.144 © KHM-Museumsverband

p.168 On loan to the Ashmolean Museum from Madison Kent Karlock (LI 12235.1)

p.172 Alinari / Bridgeman Images

p.176 Giorgio Franchetti Gallery at Ca’ d’Oro – Regional Directorate of Veneto Museums, “courtesy of the Ministry of Culture”

p.198 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

p.206 Courtesy Tomasso Art

p.208 © Wallace Collection / Bridgeman Images

p.216 DeAgostini Picture Library/Scala, Florence

p.218 Museo Ginori, Sesto Fiorentino, photo Arrigo Coppitz

p.250 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London