Photographs of the upper rooms in around 1925. In some places, paintings are hung right up to the cornices.

18

A hundred years young

The late-nineteenth-century museum designed by the architects Winders and Van Dijk relied on daylight for illumination. Before electric lighting was installed in 1976, it had to close at three o’clock in the winter. To return the institution to its original glory, it needed to be renovated and restored. The aim was to reinstitute the original circuit, so that today’s visitors can once again stroll through the old galleries. The walls have been painted in antique red, olive green and Pompeii red, just as they were in 1890, and the ornamental frames in the Rubens and Van Dyck Galleries have been regilded.

Meanwhile, the wall between these two spaces has been shifted slightly (imperceptible to visitors) to allow a connection between the galleries and the new, vertical museum. Everything has been thoroughly refreshed, from the plaster ceiling decorations to the joinery and the parquet floors. The iconic red velvet benches have also been restored, with those that were beyond saving replaced with replicas. They still serve to conceal the radiators. With its refurbished galleries, new technical systems and thoroughly renovated roof, the hundred-plus-year-old building can now embark on its new life.

19

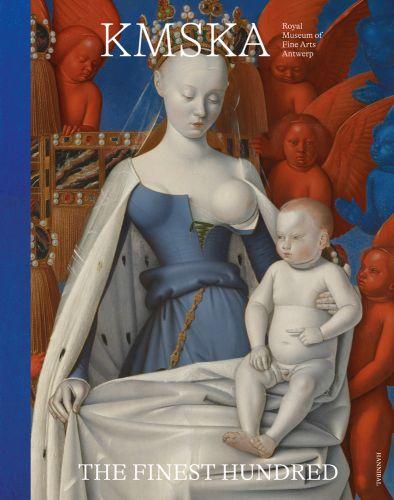

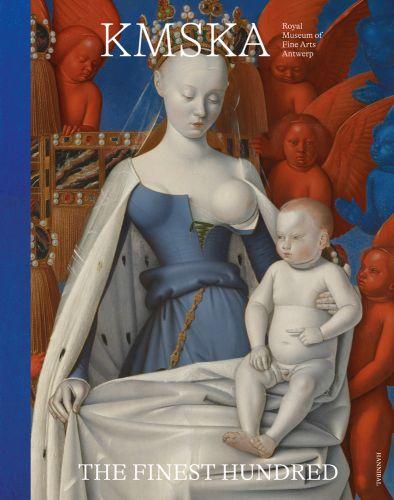

JEAN FOUQUET

A timeless masterpiece and a fantastic work with surreal colour contrasts: today, appreciation of this panel by the French court painter Jean Fouquet is unanimous. A milky white Madonna is holding Jesus on her lap as she sits on a magnificent throne, wearing an ermine cloak and a crown set with pearls and precious stones. This Mary is a queen, the Queen of Heaven no less, as she is surrounded by angels. The red seraphim were the highest in rank and they are closest to Mary, their hands on her throne. The blue cherubs – second in the celestial hierarchy –are shown praying in the background.

The baby Jesus is pointing towards the figures in the left-hand panel of this diptych, now in Berlin, in which Fouquet painted Etienne Chevalier at prayer – the man who commissioned the work in around 1450. He is accompanied by Stephen, his patron saint. The spheres to the left of Mary’s throne seem to reflect a window in the Renaissance building that forms the background to the Berlin panel. Chevalier was treasurer to King Charles VII of France and had a private chapel in the church of Notre Dame in Melun, where the diptych was displayed.

It has been suggested that Mary was based on Agnès Sorel, a legendary mistress of Charles VII She certainly resembles the surviving commemorative portrait of Sorel, who is also known to have introduced the dress with bare shoulders to the French court – not without a certain furore. Furthermore, Etienne Chevalier was her executor in 1450 when Sorel died at the age of twenty-eight.

Florent van Ertborn bequeathed the work to the museum in 1841, at which point it hardly rated a mention. Today considered a masterpiece, it has become a favourite of museumgoers.

Madonna Surrounded by Seraphim and Cherubim c. 1450

Oil on panel, 94.5 × 85.5 cm Inv. 132

PROVENANCE

Bequest of Chevalier Florent van Ertborn, 1841

LITERATURE

Claude Schaefer, ‘Le diptyque de Melun de Jean Fouquet conservé à Anvers et à Berlin’, in: Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, (1975), pp. 7–100. – Paul Vandenbroeck, Catalogus schilderijen 14de en 15de eeuw. Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, Antwerp: Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, 1985, pp. 75–77. – Stephan Kemperdick (ed.), Jean Fouquet. The Melun Diptych, exhib. cat. [Berlin, Gemäldegalerie], Petersberg: Imhof, 2018.

Jean Fouquet, Etienne Chevalier with St Stephen, c. 1450, oil on panel, 96.9 × 88.2 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, inv. 1617

54

[KB] Stunning Tours c.

1420 Tours 1477/1481

55

MAERTEN DE VOS

Antwerp 1532

Antwerp 1603

After several turbulent years during the revolt of the Low Countries, Spanish Catholic forces recaptured Antwerp in 1585. The city’s churches had been severely damaged and looted in the course of the religious troubles and the civic authorities now ordered the local guilds to spare no expense in restoring their damaged altars. This meant new paintings too. Maerten de Vos and his studio played a leading role in the restoration campaign, not least in Antwerp’s cathedral.

De Vos painted this monumental triptych for the Guild of the ‘Old Arbalest’, a company of crossbowmen, a militia company. Its central panel shows the resurrected Christ triumphing over sin and death, symbolised by the dragon and the skull which he is trampling beneath his feet. Christ’s orb and staff are references to his dominion. Seated at his feet, the Apostles Peter and Paul are each holding a volume of the New Testament containing Christ’s glad tidings.

Each guild had a patron saint, which in the case of the Old Arbalest was St George. The secondary theme of the altarpiece thus consists of scenes from the legend of St George. The saint can be seen on the far left of the central panel opposite the Princess of Silene, the woman he rescued from the dragon. Her father, the king, promptly converted to Christianity and was baptised, along with his entire population. This part of the story is shown in the left-hand panel, while the one on the right depicts the building, in gratitude, of a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary.

The message here is the victory of the Church and the true faith. Catholicism is shown triumphing over death and evil in what is undoubtedly an allusion to the religious conflict that continued to rage in De Vos’ time.

[LK]

Oil on panel, 352 × 280.2 cm (central panel) (within frame); 344.9 × 124.5 cm (side panels) (within frame) Signed and dated on the border of the carpet in the left wing: ‘ROBYCOLIUM CP…O FECIT MERTEN DE VOS ANTVERPIENSIS MDLXXXX ’ (‘Robycolium… Made by Maerten de Vos of Antwerp 1590’) Inv. 72–76

PROVENANCE

Transferred from the École centrale du Département des Deux-Nèthes, 1810.

LITERATURE

Leo Wuyts, ‘Het St.-Jorisretabel van de Oude Voetboog door Maarten de Vos: een ikonologisch onderzoek’, in: Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 1971, pp. 107–36. –Julien Vervaet, ‘Catalogus van de altaarstukken van gilden en ambachten uit de Onze-LieveVrouwekerk van Antwerpen en bewaard in het Koninklijk Museum’, in: Jaarboek Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, 1976, pp. 197–244. –Esther Meier, Nach dem Bildersturm: die Ausstattung katholischer Kirchen in Antwerpen und der niederländischen Republik, Berlin: Reimer, 2021

110

Victory!

Old Arbalest 1590

Altarpiece of the Guild of the

These two are siblings – the Amsterdam merchant Jan van der Voort on the left and his sister Catharina on the right. They are posing on a terrace overlooking a garden. Wearing a red dressing gown with Japanese touches, Jan is leaning casually against the balustrade holding a black karpoes, a style of cap. His sister is decorating her hair, adding flowers as a finishing touch. A servant is holding up the mirror for her, while the flowers lie ready in the jardinière in the foreground. Catherina is wearing a sumptuous silk gown with gold embroidery and pearls from her richly stocked jewellery box. The wealth of this family positively leaps from the canvas.

Several symbols hint that something big is brewing. The striking thistle in the lower right, for instance, stands for fidelity, while a tulip symbolises purity, and a rose, love. Pearls were an ancient symbol of chastity. Fidelity, purity, chastity and love? Is Catherina about to wed? She is indeed: on 28 February 1661 she married the Leiden cloth manufacturer and wholesaler Pieter de la Court, a business associate of her brothers Jan and Willem.

It was presumably the still-single Jan – according to family history he doted on his sister – who commissioned their Amsterdam neighbour Ferdinand Bol to paint this farewell canvas, which remained in the family for over a century. Bol, who trained under Rembrandt, was intimately acquainted with the city’s high society, for which he produced numerous portraits. This particular work was intended to be hung in a high place: only then does the perspective of the steep stairs make sense.

[SB]

Jan van der Voort and His Sister Catharina with a Servant 1661

Oil on canvas, 173.4 × 209.3 cm Signed and dated lowerleft: ‘FBol . fecit / 1661’ Inv. 812

PROVENANCE

Purchased from the art dealers J. & A. Le Roy frères, Brussels, 1903.

LITERATURE

Albert Blankert, ‘Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680), Rembrandt’s Pupil’, in Aetas aurea: Monographs on Dutch & Flemish Painting, vol. 2, Doornspijk: Davaco, 1982, p. 153. –Femke Diercks, Backer: een Amsterdamse familie in beeld, Zwolle: Waanders, 2010, p. 37 and 54. – Ellen Keppens and Jill Keppens, ‘Ferdinand Bol’s Painting Technique in Portrait of Jan van der Voort and his Sister Catharina with a Servant (1661) in Antwerp’, in: Stephanie S. Dickey, Ferdinand Bol and Govert Flinck. New Research, Zwolle: WBooks, 2017, pp. 169–71.

154

Dordrecht 1616 Amsterdam 1680

A brotherly farewell

FERDINAND

BOL

155

JULES SCHMALZIGAUG

Antwerp 1882

The Hague 1917

Lightning-fast painting

Jules Schmalzigaug was born into a wealthy Antwerp family with German roots. Having spent several years in Paris, from 1912 he mainly lived and worked in Venice. There, he developed a fascination for Italian Futurism and the question of how painters ought to depict the various phases of dynamic movement. How to convey speed on canvas: passing cars, say, or their flashing reflections in shop windows? What associations exist between colour and sound? And what emotions do they trigger? Can you use colour to determine forms? Speed, the canvas shown here, is a response to just such questions, which Futurists saw as the essence of their art.

Schmalzigaug took part in a major exhibition of International Futurism in Rome in the spring of 1914 where he met people such as the great Giacomo Balla, whose studio he would visit intensively for several months. Balla, too, was seeking ways to capture on canvas phenomena such as the flitting reflections of cars. What most occupied them was the visual representation of intangible movements, which become abstract swirls of lines and shapes in their experimental canvases, packed with colour effects.

Speed was probably created during or shortly after the exhibition in Rome. Schmalzigaug had to leave his studio in Venice in a hurry in December 1914, shortly after the First World War broke out. He sought refuge in The Hague but was unable to take his paintings with him. They were not repatriated until after the war, by which time Schmalzigaug had already committed suicide (in 1917), having suffered with his health since his youth. This work was exhibited for the first time in 1923.

Speed [1914]

Oil on canvas, 74.6 × 109.7 cm Inv. 2099

PROVENANCE

Donated by the artist’s brother, Walter Malgaud, 1928.

LITERATURE

Valerie Verhack (ed.), ‘Jules Schmalzigaug. Een Belgische futurist’, exhib. cat. [Brussels, Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique], in: Cahiers van de Koninklijke Musea voor Schone Kunsten van België, 8, Ghent: Snoeck, 2010, p. 122. – Adriaan Gonnissen (ed.), Jules Schmalzigaug – Futurist, exhib. cat. [Ostend, M u.ZEE ], Ostend: M u.ZEE , p. 81. –Ronny and Jessy Van de Velde (eds.), Jules Schmalzigaug 1882–1917: Oeuvrecatalogus, Brussels: Ludion, 2020, p. 143.

246

[AG]