First published in Thailand in 2019 by River Books Co., Ltd 396 Maharaj Road, Tatien, Bangkok 10200 Thailand

Tel: (66) 2 225-4963, 2 225-0139, 2 622-1900

Fax: (66) 2 225-3861 Email: order@riverbooksbk.com www.riverbooksbk.com

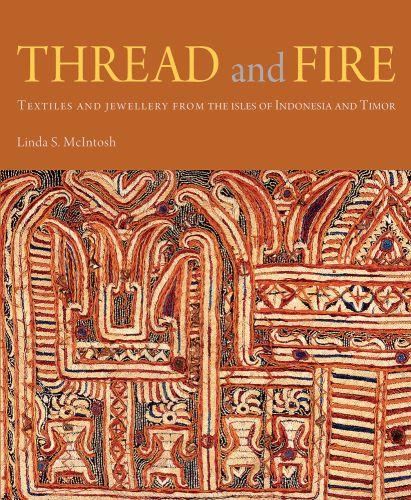

Copyright collective work © Francisco Capelo Copyright texts © Linda S. McIntosh

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher.

Publisher: Narisa Chakrabongse Production Supervisor: Paisarn Piemmettawat Graphic Design and Colour Separation: 11 Colours. Co., Ltd. Vichian Phoemthaweesuk

ISBN 978 616 4510 35 7

Cover: (Tapis Limar) Ceremonial skirt, 107 X 117 cm, 19th century, Paminggir people, Lampung, South Sumatra, handspun cotton, silk embroidery, mirror pieces, natural dyes.

Back Cover: (Lola-lola, armband) Gold, wood, glass beads, Toraja, Sulawesi; D: 17,5 cm

Opening pages: Catalogue numbers 1.25, 1.53

Printed and bound in Thailand by Bangkok Printing Co., Ltd.

7

Sumatra 15 Java 115 Bali 171 Sumbawa 207 Borneo 213 Sulawesi 235 Sumba to the Moluccas 249

Introduction

Timor 307 Glossary 331 Bibliography 337 Index 339 Contents

VIETNAMCAMBODIA

MALAYSIA

MALAYSIA

PHILIPPINES

TIMOR-LESTE

OCEAN

AUSTRALIA

Borneo Sumatra Moluccas Sulawesi Bali Lombok Sumbawa Sumba West Timor Java NEW GUINEA

THAILAND BURMA BRUNEI Flores Tanimbar Timor Sea Java Sea StraitofMalacca South China Sea INDIAN OCEAN PACIFIC

Banda Sea Celebes Sea Savu Roti Alor Lembata Solor Molucca Sea Ndao Talaud Sangihe

Introduction

In Quest of Strength and Prosperity: Shaping Culture and History in the Isles of Indonesia and Timor

Stretching across the equator, the Republic of Indonesia is a group of archipelagos that equals oneeighth the earth’s circumference in length. Composed of approximately 18,000 islands with 922 isles presenting permanent settlements, Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populous country, and Java, home of the national capital Jakarta, is its most populated isle. More than half of the country’s residents of 252 million people reside here. Over 360 official ethnic groups live in Indonesia; the majority belongs to the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian ethnolinguistic family, speaking over 700 languages and dialects. Other languages spoken in Indonesia and Timor-Leste (the island of Timor is split between two nations, Indonesia and Timor-Leste) belong to the West Papuan and TransNew Guinea ethnolinguistic families.

The Greek word for “Indian Island” inspired the name Indonesia. Prior to Dutch colonisation, historical records referred to independent or semi-independent principalities and settlements by specific names such as Srivijaya that was centred in South Sumatra and the Mataram Sultanate of Java. The archipelagos, excluding parts of Timor Island, composed the Dutch East Indies when the colonies of the Dutch East India Company (VOC: Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, 1602–1796) came under the government administration of Holland in 1800. In the early twentieth century, pro-independence citizens of the Dutch East Indies began to use the term “Indonesia”, and it was incorporated into the official name of the Republic of Indonesia when the colony achieved independence in 1949.

From approximately 1500-2000 BCE, people of Austronesian descent arrived and settled in presentday Indonesia and Timor-Leste.1 Adept sailors, they navigated the seas and alighted onto different shores. In many cultures, the founding father originated from afar, arriving by boat to establish his lineage or community. The knowledge of wet-rice cultivation that Austronesian settlers possessed led to the growth of populations that transformed villages into polities. The increase in populace gave rulers a more significant tax base, including corvée labour, and additional troops to defend and invade. The islands’ inhabitants participated in maritime commerce by sourcing natural resources to exchange for imported items such as beads, ceramics, textiles, and finished metal goods, including jewellery and tools. Most of these imports became markers of prestige and status as well as sacred heirlooms in local society.

1 Bagyo Prasetyo, “Austronesian Prehistory from the Perspective of the Comparative Megalithic,” In Austronesian Diaspora and the Ethnogeneses of People in Indonesian Archipelago. Proceedings of the

International Symposium, eds. Truman Simanjuntak, Ingrid H.E. Pojoh, and Mohammad Hisyam (Jakarta: Indonesian Institute for Social Science, 2006), 166.

7

THREAD 20 1.3 Ija Panggang Meukatap Hip wrapper, 180 x 70 cm, early 20th century, Aceh, North Sumatra, silk, metal wrapped thread, supplementary weft, twisted warp fringe. This textile glows with warmth from the use of a darker shade of maroon to frame the red central field. White threads compose the selvedges.

1.4 Ajeumat Amulet

pendant, gilt silver, filigree, granulation, Aceh, North Sumatra

L: 11

cm. Decorated with Pan-Islamic techniques of filigree and granulation, the amulet contains talismans and pieces of paper with Koranic phrases that protected to the wearer from malicious, supernatural forces.

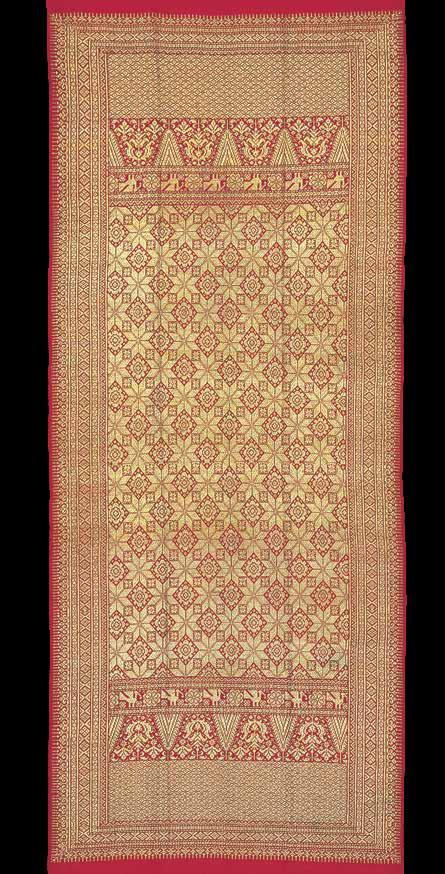

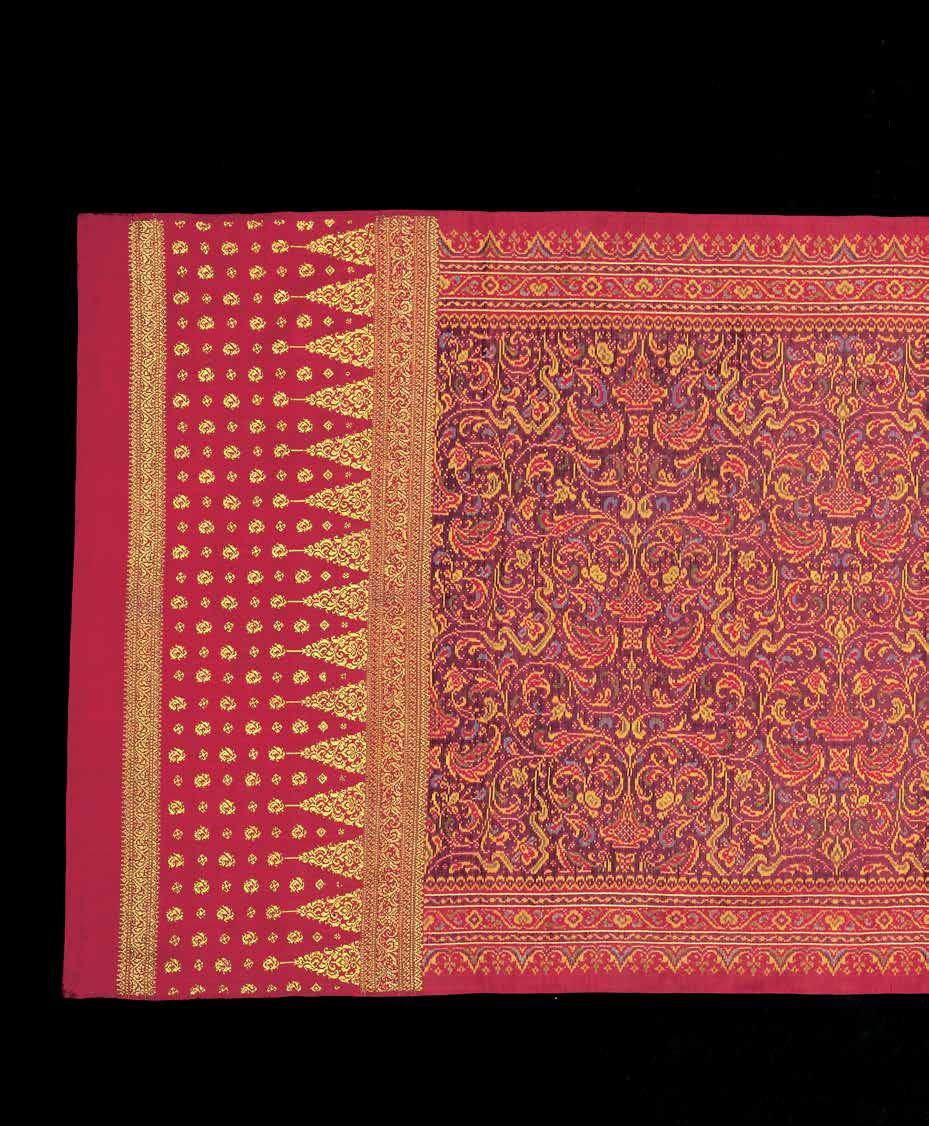

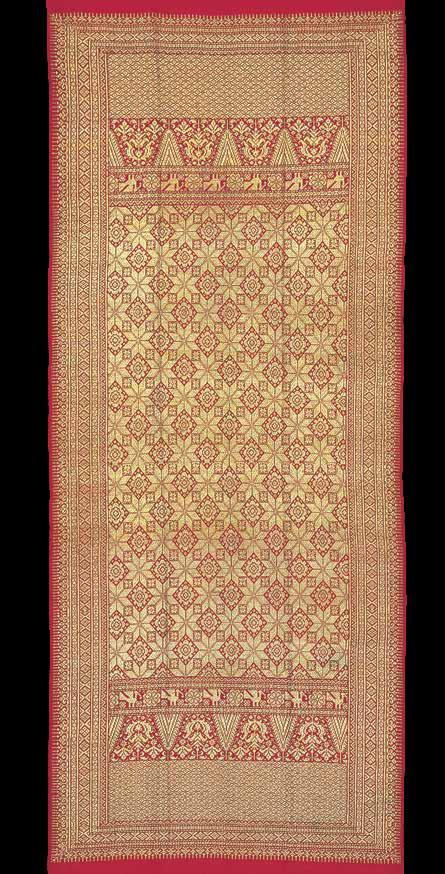

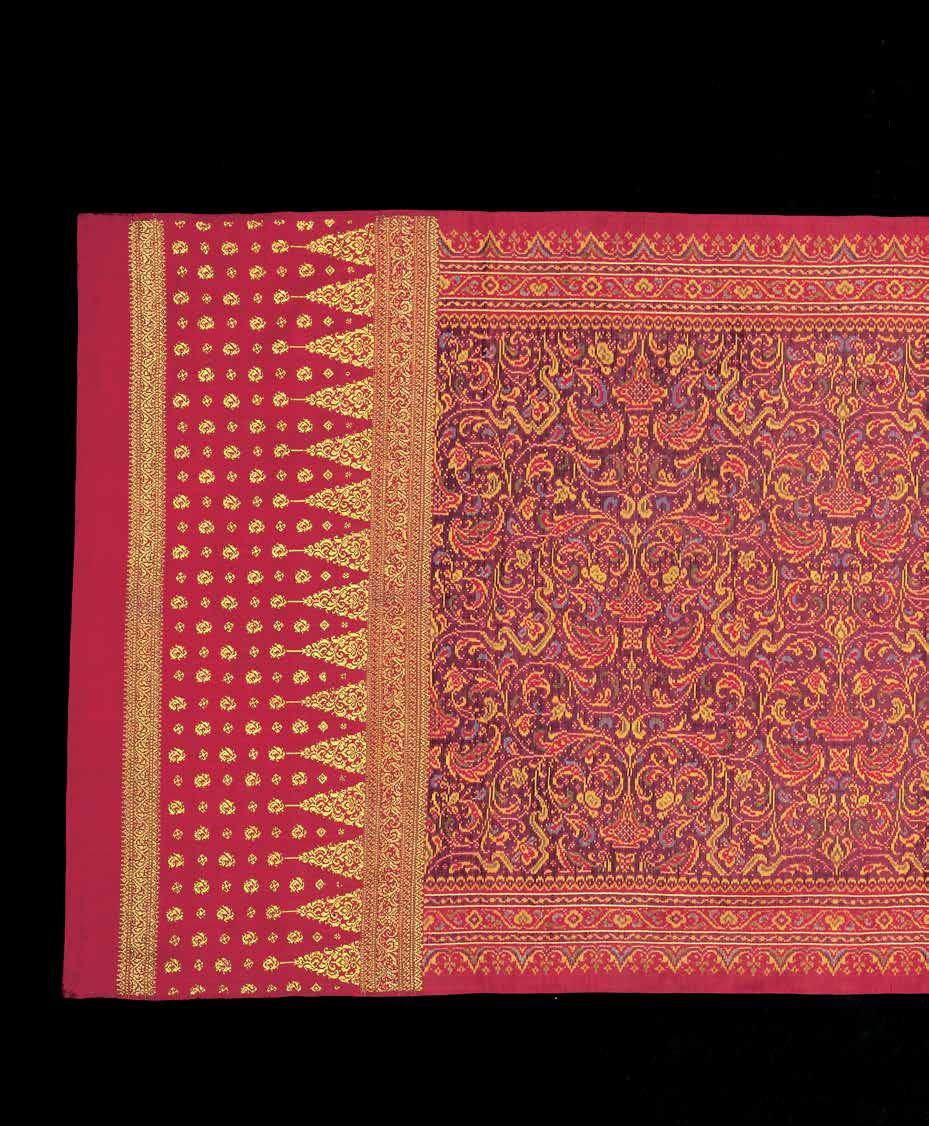

1.47 Kain Songket Lepus

Ceremonial cloth, 198 x 77 cm, late 19th century, Malay, Palembang, South Sumatra, silk, gold wrapped thread, supplementary weft. Textiles decorated with supplementary weft patterning composed of metal threads are called kain songket lepus or “cloths of gold”.

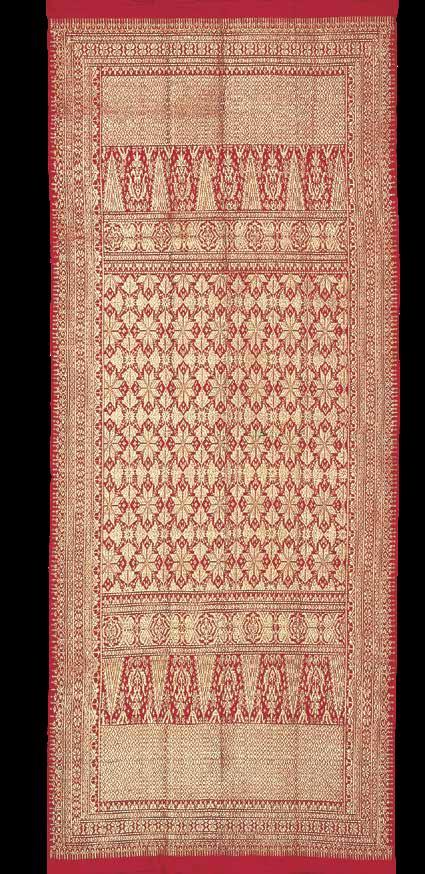

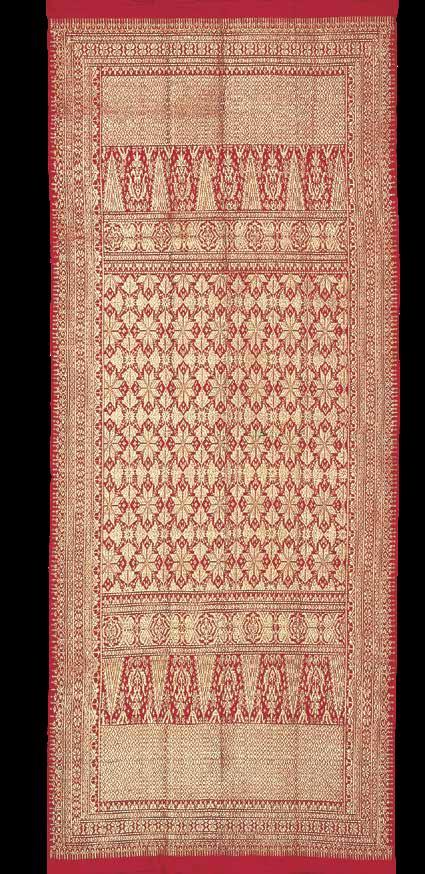

1.48 Kain Songket Lepus

Ceremonial cloth, 203 x 67 cm, early 20th century, Malay, Palembang, South Sumatra, silk, gold wrapped thread, supplementary weft. In the past, the use of “cloths of gold” was limited to the royalty and persons whom a ruler gifted such prestigious goods.

THREAD AND FIRE

and widths, and patterning may cover the garment’s entire length or be confined to the accessory’s ends to be visible when worn such as Plate 1.46.

Intra-island, inter-island, and international trade of textiles allowed high ranking and wealthy members of the Minangkabau community to consume textiles produced in other parts of Sumatra, the Indonesian archipelago, the Malay Peninsula, and beyond. Leaders and rulers invited Chinese embroiderers to their settlements, such as Palembang and Western Sumatran city ports, to produce goods. Others artisans arrived on their own, attracted by the disposable wealth of these towns’ inhabitants. Associated with Chinese textiles, satin-stitch embroidery in silk floss was applied to the ceremonial shawl in Plate 1.43. Multi-coloured blooms surround a medallion, a component of Central Asian carpets, in the garment’s centre. The embroidered blossoms are also reminiscent of South Asian aesthetics. The Minangkabau favoured Malay silk textiles decorated with supplementary weft weave in metal-wrapped threads, such as the kain songket lepus in Plate 1.44, and other luxurious fabrics not only for their expense but their foreign origin, alluding to the refinement of a well-travelled person.37 A woman applied zardozi technique originating from Turkey and Persia to velvet fabric that composes the uncang siriah or a bag that held piper betel leaves in Plate 1.45. Attached to the purse are metal tools called sapik jannguik or literally “bearded claws” used to cleanse the body.38

The Malay

Some scholars consider the former thalassocracy centred in South Sumatra, Srivijaya, to be the origin of the Malay people’s ancestors, but the definition of Malay is the subject of ongoing debate.39 The first mention of “Malayu” occurred in the seventh century CE when a kingdom from the southeast region of Sumatra sent a mission to China, and a fourteenth-century Majapahit manuscript distinguished the Malay from the Javanese and identified “Malayu lands” as areas once ruled by Srivijaya.40 The Malay language was the lingua franca of sea merchants in Insular Southeast Asia and, later, the vehicle of Islam in the region. Since the early sixteenth century, Malay identity has involved religion (Islam), language (Malay), and appropriate behaviour or custom (adat) rather than race or descent, but the definition continues to vary in Southeast Asian countries, such as in Indonesia and Malaysia, and within different regions of each nation.41

The importance of controlling the flow of goods in and out of the Indonesian archipelago continued to be key to power and wealth until the end of the nineteenth century. The dominance of any state never lasted for an extended period due to different variables, such as the demands of European and other foreign merchants and the availability of desired goods. However, Malay rulers of coastal and estuarine polities on the Malay Peninsula (present-day Malaysia and South Thailand), in Western Indonesia on the islands of Sumatra, Borneo, and in the archipelagos of Riau and Lingga grew in prominence by controlling trade to some degree. The ruling families of Malay sultanates spent their wealth on hosting ceremonies and demonstrated cultural refinement via regalia and court decoration. Like the Acehnese sultans, Malay rulers adopted aspects of Mughal court dress such as tailored upper and lower garments.

37 Use of imported textiles gave the notion that the owner a man had merantau or journeyed away from the homeland to seek knowledge and fortune. Rodgers and others, 52.

38 Richter and Carpenter, 31.

39 Anthony Milner, The Malays (Sussex: WileyBlackwell, 2009).

40 Andaya, 31-32.

41 Lieberman, 816.

Sumatra 61

2.33 Kacip, betel cutter Betel nut cutter, gold, steel, Central Java. L: 15.5 cm. The Naga serpent deity holds an elevated position in traditional beliefs and is linked to the Underworld.

2.34 Kacip

Betel nut cutter, steel, inlaid gold, semiprecious stone, Central Java. L: 19.3 cm. The image of a crowned serpent deity or Naga also appears as a batik and weft ikat motif.

176 THREAD

177 Bali

TALAUD SANGIHE

Celebes Sea

Makassar Strait

Minahassa

Minado

gorontalo

Molucca Sea Golf of Tomini

Palu Galumpang (CELEBES)

Toraja

West Sulawesi

Central Sulawesi

SULAWESI

South Sulawesi

South East Sulawesi

Sea

Bugis

Banda Sea

Java

Sulawesi

Sangihe & Talaud

The diverse population of Sulawesi, the island formerly known as Celebes, played various roles in maritime commerce since the first millennium CE. The Bugis and Makassarese, the most populous groups residing in the lowland and coastal areas of the isle’s southwest peninsula known as South Sulawesi, acquired imported goods such as ceramics, gold accessories, Indian textiles, and metal goods. They exchanged these commodities for alluvial gold, nickel-rich iron, and forest products that highland groups of the northern area of South Sulawesi, including the Mamasa and Sa’dan Toraja, sourced. Bugis and Makassarese men alighted at ports throughout Southeast Asia to sell their homeland’s natural resources and cultivated products as well as slaves, spices, and sea products originating from other isles in present-day Indonesia and Timor-Leste to acquire the goods in demand in Sulawesi and neighbouring islands. Maritime routes linked Borneo located west of the isle, the Sulu archipelago of the Philippines to its north, and the Moluccas or Spice Islands to the east. The discovery of Dongson era (500 BCE – 300 CE) bronze drums in archaeological sites on the island indicates that regional maritime trade reached Sulawesi since prehistoric times.1

Bugis and Makassarese settlements transformed into kingdoms from the thirteenth until the seventeenth centuries as their participation became more frequent and regular in maritime commerce from Mainland Southeast Asia to Australia. Unlike Sumatra, Sulawesi consisted of fertile lands ideal for rice cultivation, and some of its inhabitants exported rice to this and other islands, including the Moluccas. The amount of imported ceramics and stoneware originating from present-day China, Thailand, and Vietnam increased after 1300 and is evidence of growth in regional trade.2 Following other rulers of polities of South Sulawesi, the monarch of Gowa converted to Islam in 1605 and welcomed Muslim merchants to conduct business in his capital, Makassar. European traders who were excluded from the trade centre of Malacca after its fall to the Portuguese in 1511 also travelled to this port to purchase spices and other goods. Makassar became an active regional harbour equal in importance to Brunei on the isle of Borneo and the Sulu archipelago of the Southern Philippines regarding the sales of sea and forest products by the mid-seventeenth century. The defeat of Gowa by allied forces of the Bugis polity of Bone and the Dutch East Indies (VOC) created instability on Sulawesi, leading to the exodus of Bugis and Makassarese refugees. The sailing vessel of the Bugis, or prahu, enabled travel up rivers and across seas to acquire and exchange goods and, later, allowed large numbers of people to move to other isles in present-day Indonesia and other parts of Southeast Asia, including Thailand. Some Bugis and Makassarese migrants intermarried with members of the royalty of their new domiciles, leading to their involvement in governance.

1 Barbara W. Andaya and Leonard Y. Andaya, A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia 1400-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 27.

2 Wayne A. Bougas, “Gold Looted and Excavated from Late (1300 AD - 1600 AD) Pre-Islamic Makassar Graves,” Archipel 73:1 (2007): 111-166.

235

6.1 Pori Situtu

Shroud and rital textile, 150 x 255 cm, early 20th century, Rongkong, Central Sulawesi, handspun cotton, warp ikat. The central field contains repeating patterns of hooks that symbolise ancestors.

236 THREAD and FIRE

Sulawesi

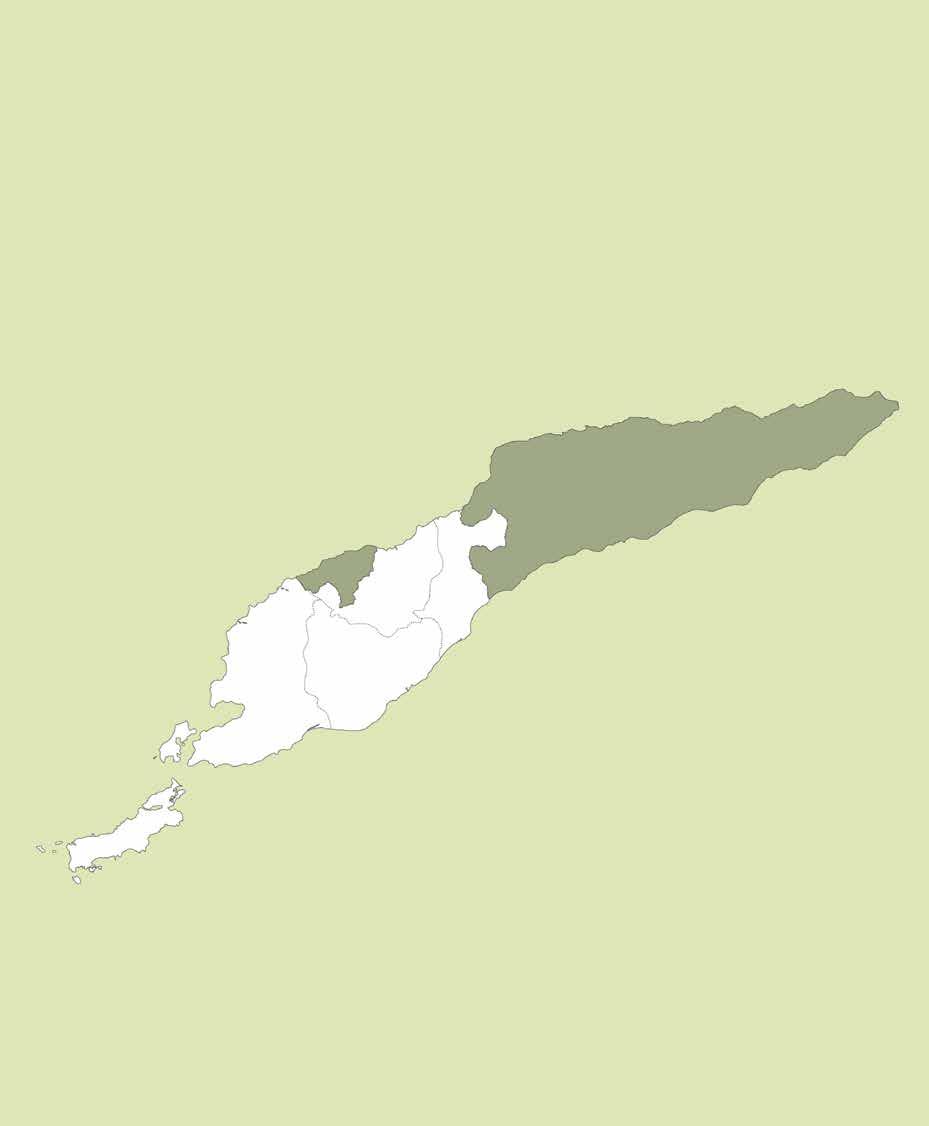

MOR-LESTE (OEKUSI)

NDAO

ROTI

TIMOR

North Central Timor South Central TimorKupang

Belu

WEST

SEMAU (INDONESIA) Savu Sea Timor Sea TI MOR-LESTE (EAST TIMOR) TI

Kapan Dili

Timor

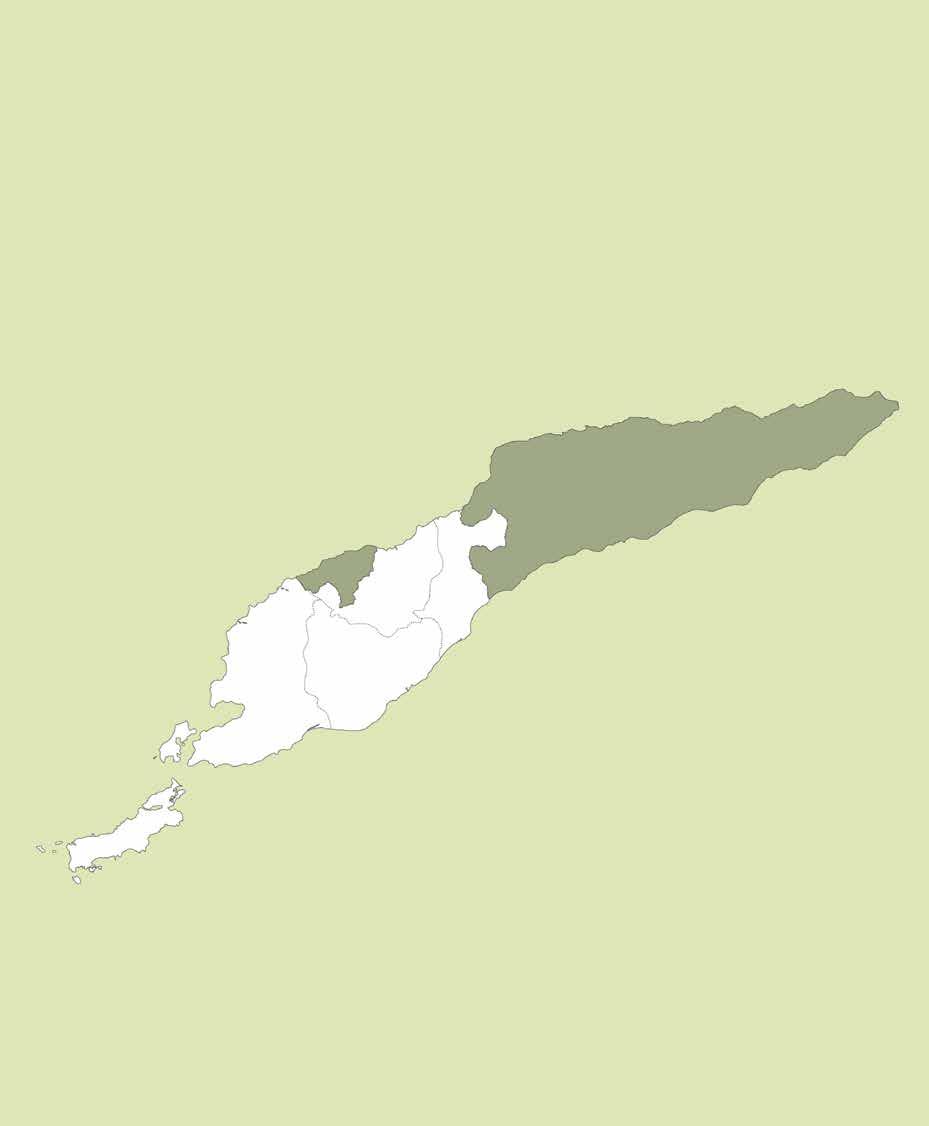

East of Roti lies Timor, an isle divided between two nations, Indonesia and Timor-Leste. West Timor or Timor Barat is part of East Nusa Tenggara Province, Republic of Indonesia while Timor-Leste is an independent nation occupying a section of the western part and the eastern half of the isle. After achieving independence from Portugal in 1975, Timor-Leste fought against its incorporation into Indonesia until 2002 when the territory gained sovereignty. The most easterly land mass of the Sunda Islands or Nusa Tenggara, Timor, is not volcanic like other isles in this chain such as Bali, and it rests on the edge of the Australia Tectonic Plate.

From the fourteenth until the sixteenth century CE, the settlements of Timor were vassals of Java’s Majapahit Empire. Forest products, such as beeswax, honey, and sandalwood, attracted traders to Timor, the most easterly isle of the East Nusa Tenggara. Bugis, Javanese, Makassarese, and Malay sailor merchants transported the island’s natural resources and slaves to ports in present-day Western Indonesia and the Malay Peninsula to exchange for glass beads, gold jewellery, and imported textiles and ceramics originating from East and South Asia. Chinese traders sought the high-quality white sandalwood (Santalum album) that grew solely on Timor, and they reached the island by the fourteenth century. One Chinese account written in the same period noted that this natural resource was available in twelve of the isle’s principalities.1 Merchants from the Middle East also alighted on Timor’s shores seeking this exotic wood whose uses ranged from an ingredient in incense and to medicine. Rulers and their families accumulated imported goods to serve as symbols of their power and position. Timor’s population organised into numerous small, semi-independent or independent settlements in the past, and each had a ruler or raja. Marital alliances linked the different principalities, and intermarriage occurred across cultural boundaries. By the sixteenth century, the Tetun kingdom of Wehali-Waiwiku, whose capital was founded near the south coast of Central Timor, emerged as the most influential realm on the island.

For some European countries, a presence on the island was crucial to manage or monopolise maritime commerce in the Eastern Indonesian archipelago. Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521) led a Portuguese expedition in search of the source of gold and glory, completing the first circumnavigation of the world from 1519-1521. He died before his crew, which included the Italian navigator Pigafetta, arrived on Timor in 1522. Pigafetta successfully reached the isle and described red fabric, linen material, and metal goods exchanged for sandalwood, honey, and slaves at its ports.2 Portuguese troops defeated the kingdom of Wehali in 1642, breaking the realm’s hegemony of Timor.3 The first Portuguese base located at Lifao later moved to Dili of present-day Timor-Leste in 1769. Portuguese settlers intermarried with the local population, and mestizos, known as the Black Portuguese, Topasses or Larantukans, intermarried with the local elite and, later, controlled the island’s sandalwood trade.

1 Barbara W. Andaya and Leonard Y. Andaya, A History of Early Modern Southeast Asia 1400-1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 20-23.

2 Stanley 1874, 136; quoted in Yeager and Jacobson, 18-19.

3 Roy W. Hamilton and Yohannes Nahak Taromi, “Malaka Regency: Cloth of the Plain, Cloth of the Hills,” in Textiles of Timor: Island in the Woven Sea, eds. Roy W. Hamilton and Joanna Barrkman (Los Angeles: Fowler Museum at UCLA, 2014), 137.

307

8.3 Belt Leather, silver, silver coins, Timor. Length: 60 cm. Since the sixteenth century, silver coinage was a trade currency in the region. Some coins were melted and fashioned into ornament, but others were left intact and used to embellish regalia, such as this meo belt.

8.4 Headband Supplementary warp-decorated cotton fabric, imported red cotton fabric, silver, glass beads, Timor. L: 105 cm. High-ranking men, such as meo warriors, wore headbands. A combination of locally made and imported cloth composes this accessory. Silver discs symbolise the moon and are adorned with images of the sun and stars.

344