WILLIAM KENTRIDGE

STEPHEN CLINGMAN

STEPHEN CLINGMAN

STEPHEN CLINGMAN

STEPHEN CLINGMAN

STEPHEN CLINGMAN

STEPHEN CLINGMAN

William Kentridge, ‘Peripheral Vision’1

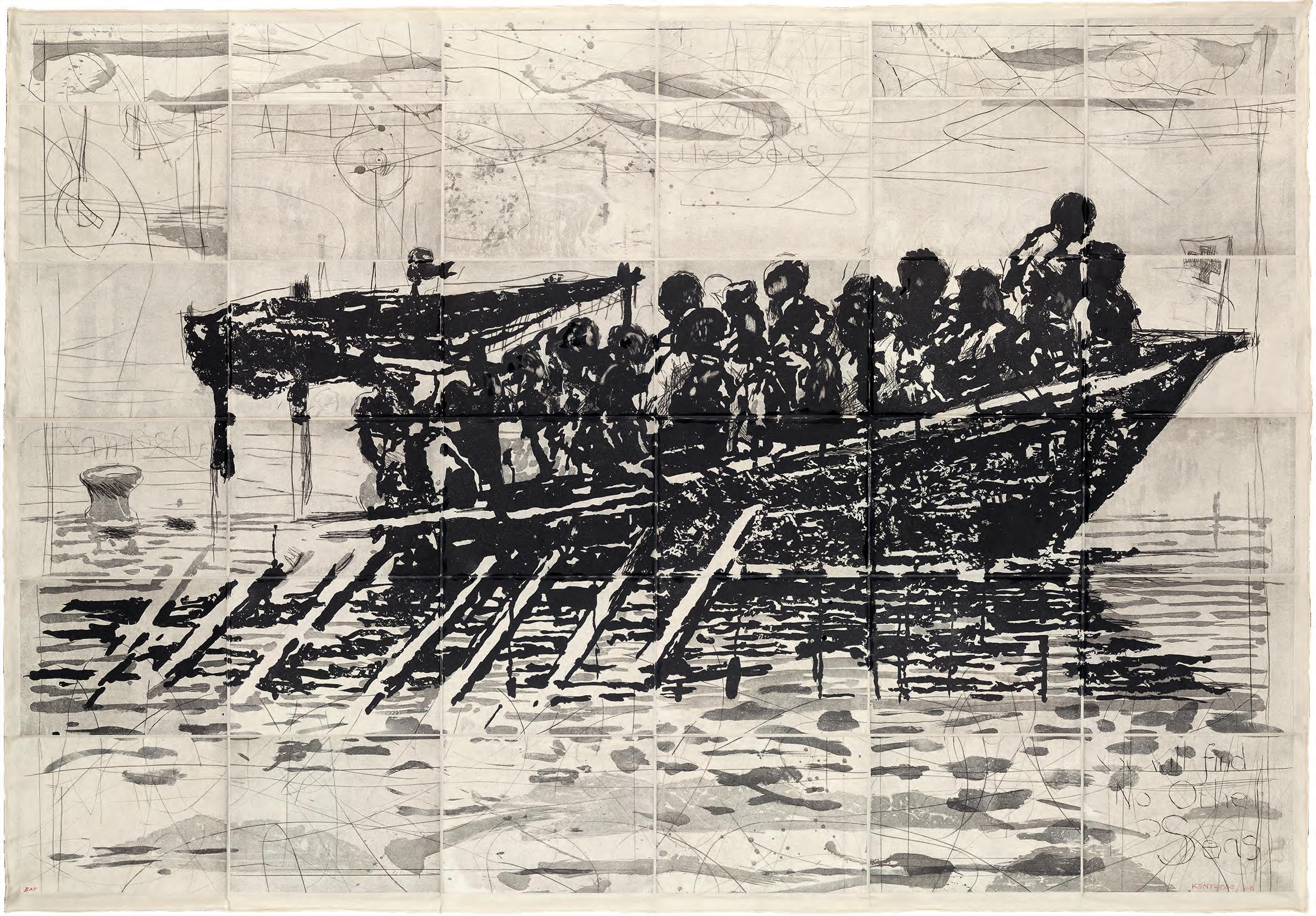

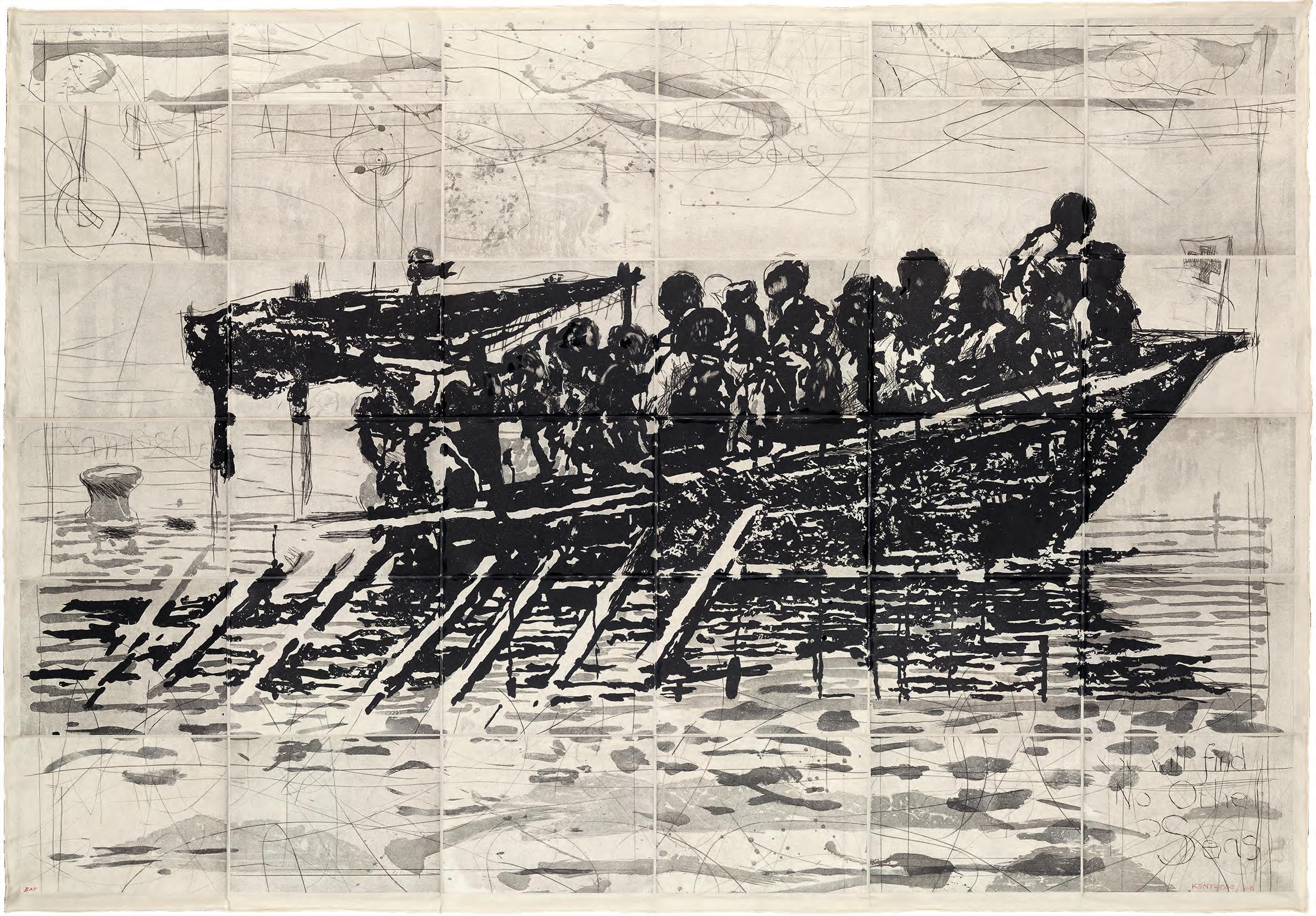

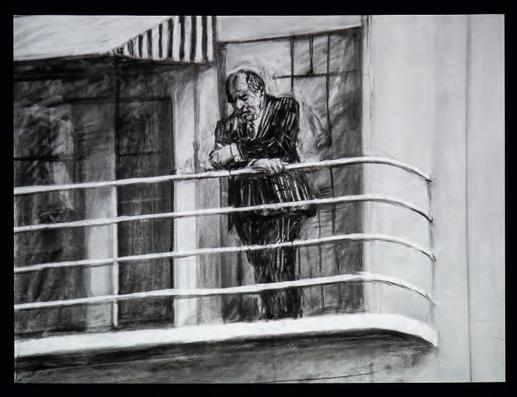

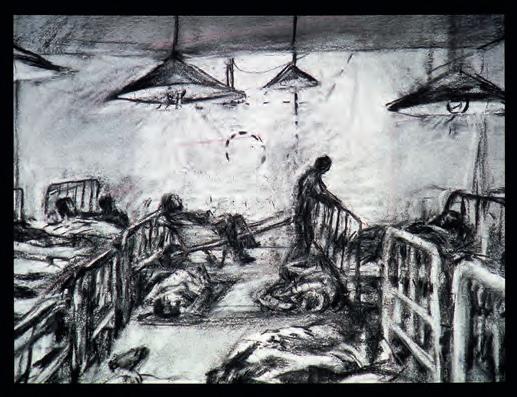

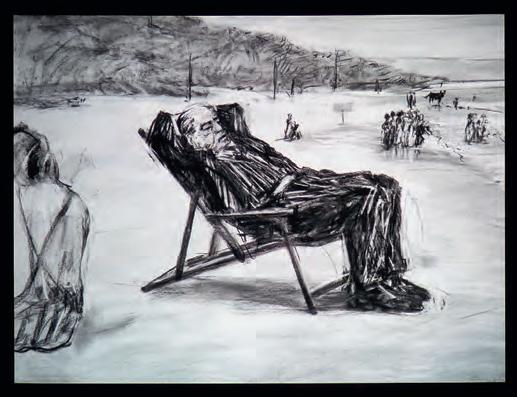

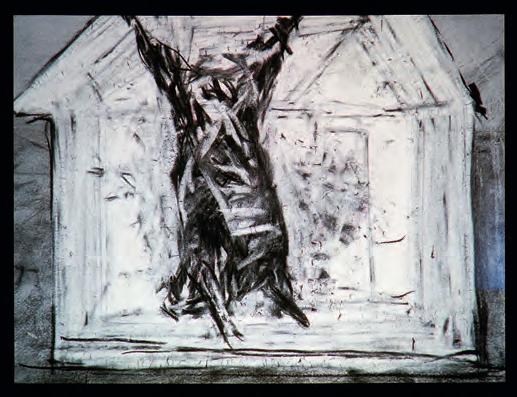

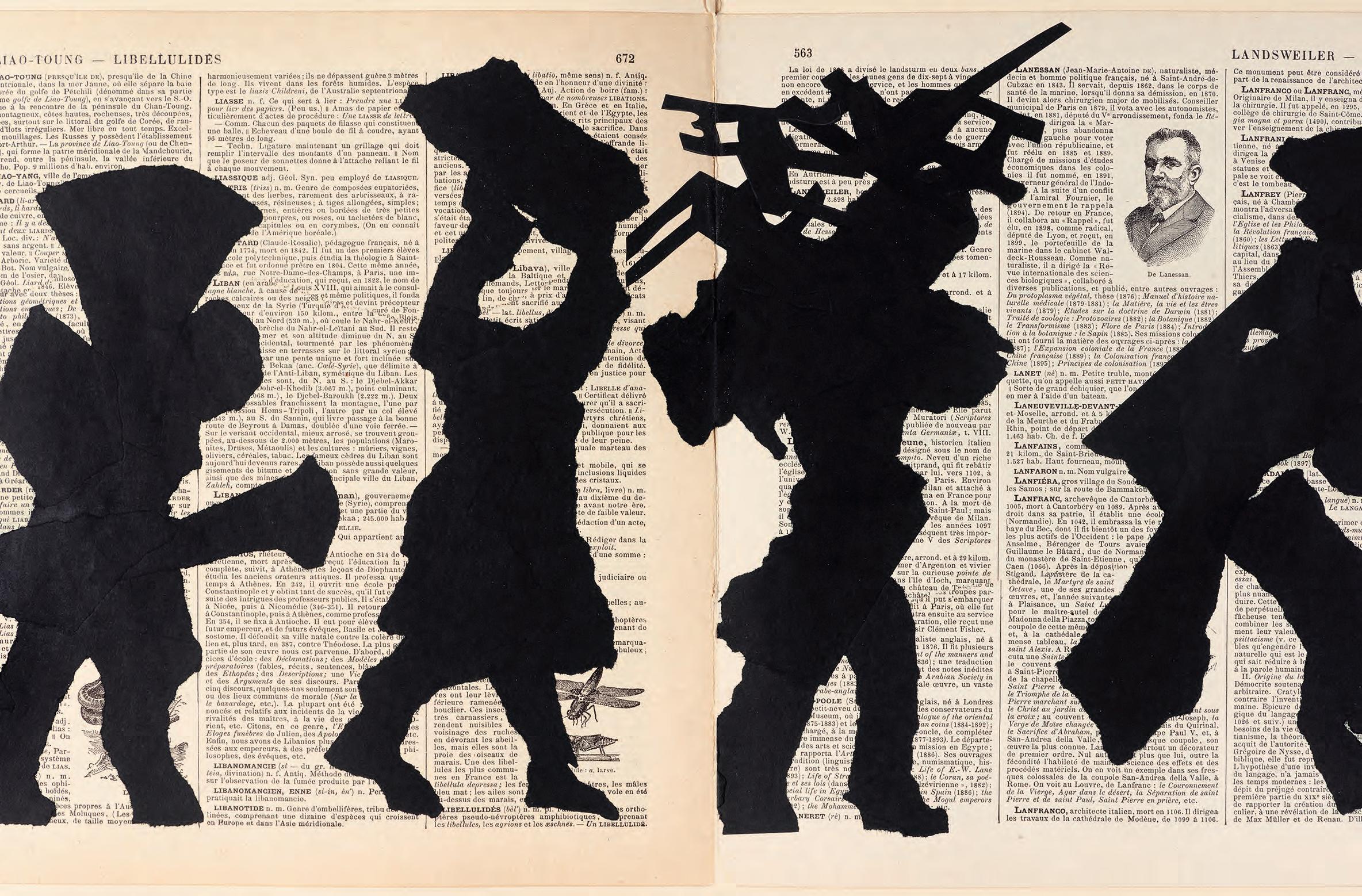

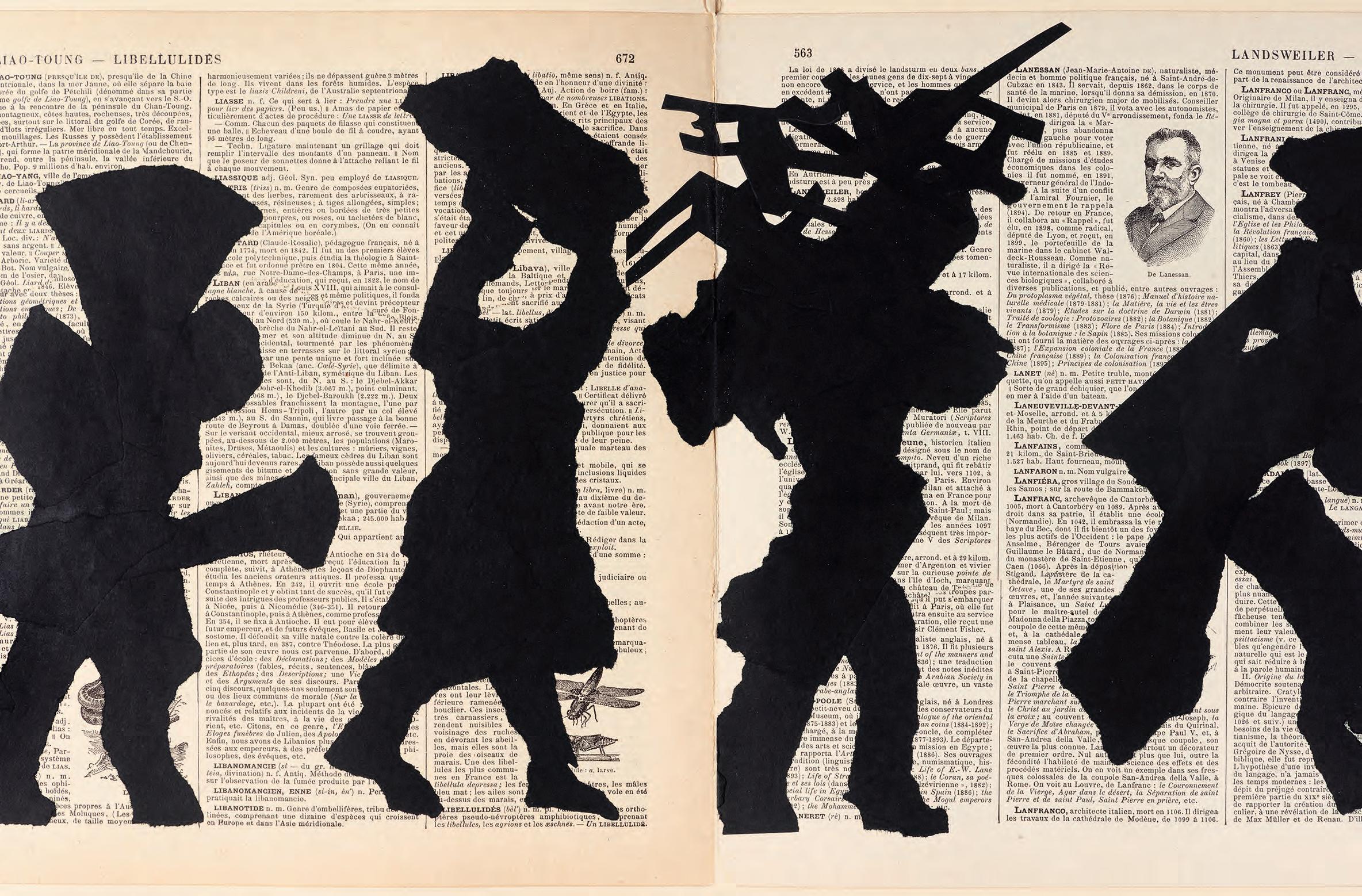

Here are some images drawn from William Kentridge’s films and other works over the years.

A typewriter turns into a tree. Leaves of paper lift in the breeze, just as the leaves of a tree would.

In a triumphant scene from a colonial film, a rhinoceros is shot by hunters; later the rhinoceros, turned gymnast, somersaults over a humanoid construction with megaphone head bearing the sign Trauerarbeit

A cat curls itself into a cartoon bomb with its fuse lit; the seconds tick away and it explodes (fig. 5).

A procession marches across the landscape, growing larger as it comes nearer.

A prevailing theme in all Kentridge commentary is the way his art takes on multiple forms. Over the years, he has worked in etching, drypoint, theatre, puppetry, opera, film, dance, sculpture, tapestry. Collage is a standard method, music flows through it all. Moreover, these modalities don’t operate in sequence but very often in combination, simultaneously. At the core of it, though, may be drawing, in both narrow and wide senses. There is drawing in Kentridge’s favoured charcoal, a medium of erasure, transition, alteration. And there is drawing in a larger sense, in which all these forms are drawn into and through one another. We have image upon image as a form of multi-dimensionality, multi-modality.

What kind of art is it? For Kentridge, drawing is a kind of thinking, thinking a kind of drawing: ‘drawing is a testing of ideas, a slow-motion version of thought… The uncertain and imprecise way of constructing a drawing is sometimes a model of how to construct meaning.’2 But if we wish to settle on a meaning in any of his works, we are unlikely to be able to do so, something that may be generally true of any complex art. Gerhard Richter remarks, ‘Pictures which are interpretable, and which contain a meaning, are bad pictures.’3 Certainly, in Kentridge’s work there are moments of sudden perception, of deep feeling or insight for the viewer, but they are not likely to be easily summarised or expressed. One leaves the work in a different state, a sensation of vision, of something shattered or seen at the periphery,

or apprehended almost as a whole condition of being. So that may be the meaning: that state of sudden disruption and introduction to a different sense of vision: the event of art.

In other words, the meaning may not be a ‘thing’ but a process, in various guises. It is the process in and behind the typical Kentridge work, a process which he often makes half-glimpsed, part of its intrinsic magnetism and mystery. There is also the process into which the viewer enters, moved by the work’s echoes and allures until some new place of vision occurs. Engaging with the work, you become part of the drawing, the work comes off the wall to engage you in your relation to it.

The key question about Kentridge’s art then is not what does it mean but what does it do. The ‘doing’ is a question of technique and process which becomes nothing less than the totality of the work itself, a totality which will generally exceed its apprehension. For the artist it is a matter of vision which both engenders and grows out of that process. And because of this, for the viewer it is also a matter of its effects in the moment of engagement and after, whether those effects are conceptual, intuitive or emotional. It is out of these many dimensions of ‘doing’ that we might arrive at a deeper and refashioned sense of meaning in Kentridge’s work. Its meaning is what it does.

Inspiration, from spirare: to breathe, draw in breath. Or: to draw; in breath; in movement. This is where it begins.

35 mm animated film transferred to video, 8 minutes 22 seconds. William Kentridge Studio, Johannesburg

William Kentridge had his own beginnings in South Africa, and lives there to this day. He came from a very specific world. His paternal great-grandfather, Woolf Kantrovich, emigrated from Lithuania via England to South Africa. As his name suggests, he was a synagogue cantor, and subsequently a rabbi. By 1912, the family had changed the name to Kentridge to suit its anglicised surroundings. William Kentridge’s grandfather, Morris Kentridge, took to politics and was briefly jailed for his prominent role in supporting the white miners in the Rand Rebellion of 1922; in 1924 he was elected a Labour Member of Parliament, combining both his socialist and Zionist commitments with a preference for protecting the privileges of the country’s white workers.4 Kentridge’s maternal grandmother, Irene Geffen (née Newmark), was the first female advocate in South Africa (and the first woman to obtain a driving licence). His mother, Felicia Kentridge, was also a lawyer and a co-founder of the Legal Resources Centre, which did indispensable work in opposing apartheid legislation. His father, Sydney (later Sir Sydney) Kentridge, was one of South Africa’s most famed anti-apartheid lawyers, appearing for the defence in the epic Treason Trial (1956–61), in which all 156 accused were acquitted, and in the inquest into the death in detention of the Black Consciousness leader Steve Biko, where he represented the Biko family. In 1955, when William Kentridge was born, his lineage had emerged generationally from a relatively sequestered history into one that was prominent and revered,

identifiably part of a Johannesburg professional elite, if not aristocracy. In the not-too-distant past was a world of marginalisation and migration; in the present there were confidence and solidity.

Metamorphosis was therefore part of his story, and yet there were also constants in the life of his family. One would have been a sense of cultural affiliation to the long legacies of Europe, even if distantly in Africa. Another would have been the commitment of both his parents to issues of morality and justice, and to the rationalities of the law as a lens for seeing (and improving) the world. Paradoxes and contradictions abounded. On the one hand, his father defended South Africans of various races committed to the overthrow of apartheid. On the other, William went to a school set in the colonial mould, segregated twice over by race and gender, and coloured by the pervasive habits of superiority. Kentridge’s family was anti-apartheid to its bones; yet, living in a home in one of the most select Johannesburg suburbs, it also occupied a position of privilege based on the system it opposed. This would have been a matter of daily acknowledgement.

Yet it is this very same world, now both transformed and untransformed in the aftermath of apartheid, that has always been William Kentridge’s home, and the energy source for much of his work. It is a place that in a fractured and fragmented form joins the here with the there, the self with the other, the now with the then, and where the future is an open question, a place without a clear boundary or horizon. Again, this is not a bad way to think of his art.