7 minute read

DECIPHERING DEI

from National Culinary Review (Sept/Oct 2022)

by National Culinary Review (an American Culinary Federation publication)

What diversity, equity and inclusion mean to the LGBTQ community // By Lauren Kramer

Creating a diverse, equal and inclusive culture in the workplace is something that many companies promise but few are able to fully deliver, particularly when it comes to the inclusion of members of the LGBTQ community. In the kitchen — as in many other environments and workplaces — there’s much room for improvement, and it can only truly be accomplished with education.

That’s the message from Vanessa Sheridan, a transgender consultant, speaker and author of “The Complete Guide to Transgender in the Workplace.” Sheridan has spent the past three decades consulting with organizations across the country and notes that workplaces in general tend to fester with microaggressions toward people who are different. Cumulatively, these can have a devastating effect over time.

“Sometimes people are simply unaware of the need to be professional to those who are different,” Sheridan says, “while other times they’re ignorant of the harm they’re causing, and for some, it’s that they’re simply mean-spirited.”

The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines microaggression as “a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group (such as a racial minority).”

According to Sheridan, microaggressions can take a variety of forms, from calling someone the wrong name to using the wrong pronouns, using slurs or even withholding information that person needs to get the job done. “When this kind of

RED FLAGS IN THE WORKPLACE:

• R epeated incidents of someone being called by the wrong name or pronouns

• Negative subtleties in interpersonal interactions over an extended period of time

• I nsensitive use of language, such as “sexual choice”

• Use of slurs or the pronoun “it” to refer to transgender people behavior is done purposefully and continuously over time, it takes an emotional and psychological toll and creates a hostile environment,” she says. “That’s why training is so important, to teach organizations and their people to be respectful and professional. If everyone would just focus on that, it would eliminate a lot of problems.”

Calling a transgender individual “it” is simply dehumanizing, Sheridan says. “People don’t have a sexual choice, they have an orientation. And they don’t choose their gender identity, they simply recognize what it is and act on it.” The phrase “transgender lifestyle” is also erroneous. “There’s no discernable lifestyle that exists, just millions of transgender people living their lives.”

A diverse workplace is a flourishing environment where a wide variety of perspectives and worldviews come to the table, she adds. “The view from the margins is always more interesting than the view from the center. In a diverse, inclusive environment, the pool of breakthrough ideas widens, and it becomes easier to create fresh new products and services. That’s one of the reasons I encourage every organization to think about diversifying as much as possible.”

Sadly, the reality is that many transgender people deal with negativity and disparagement on a regular basis at work — and that’s if they can find work. “The unemployment rate for the transgender community is at least twice the national average, and it’s even more if you’re a trans person of color,” Sheridan says. “Unemployment and underemployment are major problems, and I think the foodservice industry needs to be aware of that.”

“Transgender people are certainly capable and able to provide excellent contributions if given the opportunity,” she reflects. “The problem is getting the opportunity, which starts with the hiring process. We need to educate hiring managers about the importance of looking into the trans community as a potential source for employment and to create conduits between the business community and the trans community.”

Awareness that a problem exists is the first step to addressing that problem and creating a solution, which often involves staff training. “We need top management in an organization to simply say, ‘We don’t tolerate discrimination, harassment or bullying in our workplace, and if you’re found doing that, we’ll take steps to manage it, up to terminating the employment,’” Sheridan says.

Two Miami-based Colombian chefs combine their heritage cuisine with Asian elements

//

By Kenya McCullum

For Colombian-born Chef Cesar Zapata, incorporating a Latin flair into the Vietnamese cuisine he serves at his restaurant, Phuc Yea, makes sense. When he opened the Miami restaurant six years ago, it wasn’t getting the traction he wanted because locals just weren’t familiar enough with Vietnamese food to give it a try.

“I think the fact that we live in Miami — and we have such a huge Latin population here — and Vietnamese was pretty new to the city, we were having difficulties trying to get people into the restaurant just because they were not very familiar with the food,” Chef Zapata says. “And then I started thinking: Colombian ingredients, or just a lot of Latin American ingredients, that we use are also utilized in Southeast Asia, especially in Vietnam. So it just kind of makes sense to blend those ingredients together and fuse both cuisines. And little by little, I just started adding those dishes, and people loved them and were like, ‘Oh my God, this is delicious. This is completely new and different.’ Not only that, but the Asian community started to embrace the fusion, so eventually we just kept going with it and then I guess something new was born.”

What was born was a combination of Vietnamese and Latin food that leverages the similarities of both cuisines, making a delicious marriage that is perfectly consummated on the palate. Chef Zapata points out that both cuisines share certain ingredients — yucca, plantains, different types of tubers, corn, cilantro and chiles, as well as tropical fruits like mango, avocado and papaya.

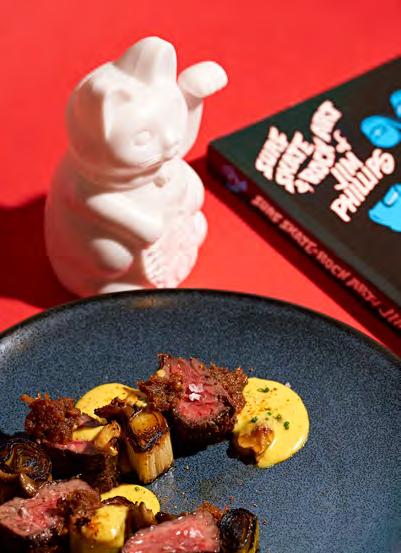

One dish that Chef Zapata says lends itself to the Vietnamese-Latin fusion is a pepper steak that uses many of the same ingredients and even the same cooking tools.

“In Vietnam, there’s a pepper steak that’s very similar to a lomo saltado,” Chef Zapata says. “This is a Peruvian beef dish, which is also done in a wok because Peru also has a lot of Chinese influence, so it’s almost the same ingredients. It has onion, tomatoes, soy sauce and [other ingredients] here and there that change but are still very similar.”

Of course, there are characteristics of Vietnamese and Colombian cuisines that are not so similar. For example, Chef Zapata notes that Vietnamese cuisine uses a lot of fermented products, like fish sauce and different types of paste, as well as a variety of curries, which are not utilized in the country he calls home but that he enjoys incorporating into his dishes.

Additionally, cooking techniques in Vietnam tend to be more Frenchinfluenced, while Colombian cuisine heavily favors Spanish techniques. For example, an avocado used in Colombian cuisine is mostly found in salads and other savory foods, while that same avocado in Vietnam is used as a fruit, so it’s often found in desserts and shakes. One example of how Chef Zapata works through the differences to make the perfect fusion is his take on ceviche.

“If I’m going to do something, it’s something that’s going to enhance the dish,” he says. “So for example, I’ll create a Vietnamese-style ceviche. We call it ceviche because if we were to call it what they call it in Vietnam, people won't order it because they wouldn’t understand the name. Then let's say it’s that same ceviche, and we will serve it with tostones — which is very traditional in the coastal regions of Colombia

— versus how in Vietnam, they'll serve it with rice crackers or maybe some taro chips.”

The Peruvian-style leche de tigre, or marinade for the ceviche, consists of garlic, shallots, lemongrass, Vietnamese basil, calamansi, lime juice, fresh cilantro, sate (lemongrass chile oil that’s made in-house), nuoc cham (fish sauce), Thai bird chiles, kaffir lime leaves and sesame oil. “We mash the garlic, shallots, lemongrass and Thai bird chiles until it becomes a paste, and then we add the fresh cilantro and Vietnamese basil, continuing to mash before adding the fish sauce and all other citrus.” The fresh shrimp, scallops and octopus get marinated in the leche de tigre, and the ceviche is served with a garnish of diced jicama and cucumber.

For Chef Zapata, cooking through these differences boils down to treating both types of cuisines with the respect they deserve.

“I try to respect both cuisines as much as I can, and I also try to do things I enjoy myself,” he says. “The challenge is making sure that people are going to embrace it and like it. I try to do a little research, too, and make sure I'm not doing something crazy that people are going to hate.”

The owner of Miami’s Zitz Sum, Colombian-born Chef Pablo Zitzmann, takes a similar approach when mixing Asian influences with the flavors he misses from home.

“I love everything about Asian food — strong flavors, different ingredients, lots of textures — and I think that, with the sweetness and the acidity from Colombian food, makes it blend perfectly,” he says. “A great example of this is coconut rice in its various forms — from arroz con titote in Colombia to Filipino coconut rice to Thai curries with coconut.”

For a roasted fish curry combining Latin and Colombian flavors, Chef Zitzmann makes coconut rice with titote, a Colombian caramelized coconut concentrate.

To make the dish, Chef Zitzmann says, “basically, you take the fresh coconut and peel it to get the meat of the coconut; then you grate it to get the first milk of the coconut. Cook that milk down in a copper pot and let it reduce until the solids and the liquids separate. The solids of the coconut, which are the fat and the sugar, eventually drop down to the bottom of the pot. Then you start caramelizing, and once it's caramelized, you filter it, and what's left on the filter is what you use to cook the rice with. Then you can use the leftover liquid to make different preparations, like soup.”

Although the combination of Asian and Colombian flavors may be new to some customers, Chef Zitzmann finds people are very receptive to giving his re-imagining of Asian food a chance, and they ultimately enjoy his dishes.

“Nowadays people are open to try different things,” Chef Zitzmann says. “For the most part, I think the people that have tasted those combinations are very surprised, and they're very happy that they were introduced to certain ingredients they didn't know before.”