SOUTH AMERICAN CUISINE

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2020

If you like to play with fire, you belong with us Membership. Certification. Online Learning Center. Apprenticeship. Events. WeAreChefs.com. ACFchefs.org.

FEATURE STORIES 26

The Cuisine of South America

A sensory exploration and brief historical journey of the cuisines of Brazil, Venezuela, Chile and beyond.

DEPARTMENTS

12 Management

Culinary education today looks a lot different than last year, or even last semester. Here’s how some chef-instructors are approaching virtual and remote learning.

16

Main Course

Even in an era of plant-based eating, whole-animal butchery hasn’t gone away and presents a more environmentally friendly — and cost effective — approach to meat prep.

19

On the Side

In-house butchery requires special consideration when it comes to knife selection and maintenance. Plus, a fresh look at rabbit.

22

Pastry

Crème anglaise, the simple dairy-and-egg-yolk combo and workhorse of every pastry kitchen, makes a comeback as consumers trace comforting classics.

24

Classical vs. Modern

A study of the classic French dish, poulet sauté a la Bourguignonne, from Chef August Escoffier’s book, along with a modern pavé version by Chef J. Kevin Walker, CMC. 36

40

Health

The wide breadth of seafood from Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico offers chefs opportunities to introduce dishes that are both flavorful and good-for-you.

At the Bar

Many bars may be closed at the moment due to COVID-19, but we can still learn how to make a trendy tea-based cocktail, or ones with decorative garnishes.

WEARECHEFS .COM 3

IN EACH ISSUE 4 President’s Message 6 On the Line 8 News Bites 14 Chapter Close-Up 34 Chef-to-Chef 42 ACF Chef Profile 46 The Quiz

Editor-in-Chief

Amelia Levin

Creative Services Manager

David Ristau

Graphic Designer

Armando Mitra

Advertising and Event Sales

Eric Gershowitz

Jeff Rhodes

Director of Marketing and Communications

Alan Sterling

American Culinary Federation, Inc.

180 Center Place Way • St. Augustine, FL 32095 (800) 624-9458 (904) 824-4468 Fax: (904) 940-0741 ncr@acfchefs.net ACFSales@mci-group.com www.acfchefs.org

Board of Directors

President

Thomas Macrina, CEC®, CCA®, AAC®

National Secretary

Mark Wright, CEC, AAC

National Treasurer

James Taylor, CEC, AAC, MBA

American Academy of Chefs Chair

Americo “Rico” DiFronzo, CEC, CCA, AAC

Vice President Central Region

Steven Jilleba, CMC®, CCE®, AAC

Vice President Northeast Region

Barry R. Young, CEC, CCE, AAC

Vice President Southeast Region

Kimberly Brock Brown, CEPC®, CCA, AAC

Vice President Western Region

Robert W. Phillips, CEC, CCA, AAC

Executive Director

Heidi Cramb

The National Culinary Review® (ISSN 0747-7716), September/ October 2020, Volume 44, Number 5, is owned by the American Culinary Federation, Inc. (ACF) and is produced 6 times a year by ACF, located at 180 Center Place Way, St. Augustine, FL 32095. A digital subscription to the National Culinary Review® is included with ACF membership dues; print subscriptions are available to ACF members for $25 per year, domestic; nonmember subscriptions are $40. Material from the National Culinary Review®, in whole or in part, may not be reproduced without written permission. All views and opinions expressed in the National Culinary Review® are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the officers or members of ACF. Changes of mailing address should be sent to ACF’s national office: 180 Center Place Way, St. Augustine, FL 32095; (800) 6249458; Fax (904) 940-0741.

The National Culinary Review® is mailed and periodical postage is paid at St. Augustine, Fla., and additional post offices.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the National Culinary Review®, 180 Center Place Way, St. Augustine, FL 32095.

As we move through these challenging times and watch as our industry has changed dramatically, it’s easy to feel down or stuck. While I have both good and bad days, I’ve tried my best to look at the silver lining: This is truly a chance to change, grow and improve. Many of us have been forced to slow down (or speed up), shift quickly and rethink old strategies to find new ways to serve people. It’s no surprise ACF members are at the forefront of those changes, speedily transitioning to curbside delivery, launching grocery stores in hospital cafes, sending hot meals and care kits to the elderly and those in need, and even launching new foundations and programs to help raise money for others.

During this time of volatility in our society and industry, I couldn’t be more excited to come back on board as your president. Please know we as a board are working tirelessly to meet your needs by listening to your concerns, suggestions and feedback while growing and strengthening our organization. It is our goal to get us up to speed now while looking forward to 2021 and the possibilities in front of us. It may be hard to think ahead when every day can bring a new surprise, but I believe we have a bright future because our member base is made up of the best and brightest minds in our industry.

As an ACF member since the mid-1970s and former president from 2013 to 2017, many of you already know a little about me. But, as we have so many new members, I would like to briefly introduce myself. In addition to serving two terms as ACF president, I also served as ACF national secretary for one term, American Academy of Chefs chair for two terms and American Academy of Chefs vice chair for two terms. I also have served as an apprentice chair and as a competition judge and have helped with many international competitions. In 2004, I coached the ACF Youth Team, and have since been involved in other team competitions as a business manager. I’m also the chair of the ACF Educational Foundation.

My culinary career began after receiving my Associate of Science degree, with honors, from The Culinary Institute of America, Hyde Park, New York, in 1976. I went on to serve as executive chef at a variety of resorts and hotels. In 2011, I joined US Foods as an executive chef/product specialist manager for the Philadelphia division and was selected in 2013 as a Food Fanatics Chef for the company, a position I still hold.

But enough about me. I want to extend a huge thank you to the ACF events team for their incredibly hard work in putting together the ACF’s first-ever virtual convention, all within just a matter of weeks. Based on the feedback I received from ACF member and non-member participants alike, the virtual convention was a success, and the sessions and speakers were stellar.

As I write this letter, ChefConnect: Nashville is set to be a hybrid event, with some in-person sessions (masks and social distancing required) as well as live-streaming for a virtual option. We are closely monitoring the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and state guidelines in case we need to move to a more remote setup.

Either way, based on the success of the 2020 ACF Virtual Convention, we know our group has the capability to come together, even during challenging times, and continue to share ideas and best practices while making new connections and maintaining our longtime friendships. To register or learn more about the safety protocols we are implementing for the event, visit acfchefs.org.

Speaking of making connections, if you haven’t already done so, I encourage you to check out Chef’s Table, ACF’s new online community forum, launched this summer. This forum was intended to be a tight-knit, private space for you, our members, so you can share ideas and talk to one another. Connectivity and community has always been a key component of ACF membership, but in today’s world, they are even more important.

As we move forward, feel free to continue to reach out to ACF and any and all board members, including me, with a call or email. We take our positions as board members extremely seriously because we know you elected us to lead as well as to serve you. Now is the time for new beginnings. Together, let’s continue to be agents of progress — not only for our organization, but for the industry at large.

Thomas “Tom” Macrina, CEC, CCA, AAC National President American Culinary Federation

4 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | President’s Message | Un Mensaje Del Presidente |

Contact me at tmacrina@acfchefs.net or follow me on Twitter @cheftommacrina and Instagram

@cheftommacrina

A medida que avanzamos en estos tiempos desafiantes y vemos cómo nuestra industria ha cambiado drásticamente, es fácil sentirnos deprimidos o estancados. Si bien tengo días buenos y malos, he hecho todo lo posible para ver el lado positivo: Esta es una verdadera oportunidad para cambiar, crecer y mejorar.

Muchos de nosotros nos hemos visto obligados a bajar la velocidad (o a acelerar), cambiar rápidamente y repensar viejas estrategias para encontrar nuevas formas de ofrecer nuestro servicio. No es de extrañar que los miembros de ACF estén a la vanguardia de esos cambios; muchos pasaron rápidamente a ofrecer servicios de entrega de puerta en puerta, abrieron tiendas de comestibles en los cafés de los hospitales, enviaron comidas calientes y kits de atención a los ancianos y los más necesitados, e incluso crearon nuevas fundaciones y programas para ayudar a recaudar dinero para otros.

Durante este tiempo de volatilidad en nuestra sociedad e industria, no podría estar más emocionado de incorporarme como su presidente. Sepan que, como junta, trabajamos incansablemente para satisfacer sus necesidades escuchando sus inquietudes, sugerencias y comentarios, y a la vez esforzándonos en pos del crecimiento y el fortalecimiento de nuestra organización. Nuestro objetivo es ponernos al día ahora mientras esperamos el 2021 y las posibilidades que tengamos por delante. Tal vez sea difícil pensar en el futuro cuando cada día puede traer una nueva sorpresa, pero creo que tenemos un futuro brillante por delante, porque nuestra base de miembros está conformada por las mejores y más brillantes mentes de la industria.

Dado que soy miembro de ACF desde mediados de la década de 1970 y fui presidente entre 2013 y 2017, muchos de ustedes ya saben un poco sobre mí. Sin embargo, como tenemos tantos miembros nuevos, me gustaría presentarme brevemente. Además de cumplir dos mandatos como presidente de la ACF, también me desempeñé como secretario nacional de la ACF durante un mandato, presidente de la Academia Estadounidense de Chefs durante dos mandatos y vicepresidente de la Academia Estadounidense de Chefs durante dos mandatos. También me desempeñé como aprendiz de director y como juez de competencia y he ayudado en muchas competencias internacionales. En 2004, entrené al Equipo Juvenil de la ACF y desde entonces he participado en otras competencias de equipos como gerente comercial. También soy director de la Fundación Educativa ACF.

Mi carrera culinaria comenzó después de recibir mi título de Asociado en Ciencias, con honores, del Instituto Culinario de América, Hyde Park, Nueva York, en 1976. Luego de eso me desempeñé como chef ejecutivo en una variedad de complejos turísticos y hoteles. En 2011, me uní a US Foods como chef ejecutivo/ gerente especialista en productos para la División de Filadelfia y en 2013 fui seleccionado como Chef Fanático de los Alimentos para la compañía, un puesto que todavía ocupo.

Pero ya basta de hablar de mí. Quiero dar muchísimas gracias al equipo de eventos de ACF por su increíble y arduo trabajo en la preparación de la primera convención virtual de ACF, todo en cuestión de semanas. Según los comentarios que recibí tanto de los miembros de ACF como de los participantes no asociados, la convención virtual fue un éxito y las sesiones y los oradores fueron estelares.

Mientras escribo esta carta, ChefConnect: Nashville se prepara para ser un evento híbrido, con algunas sesiones presenciales (con máscaras y distanciamiento social), así como también transmisiones en vivo para quienes asistan en forma virtual. Estamos siguiendo de cerca los lineamientos de los Centros para el Control y la Prevención de Enfermedades y las pautas estatales en caso de que necesitemos pasar a una configuración más remota.

De cualquier manera, basándonos en el éxito de la Convención Virtual ACF 2020, sabemos que nuestro grupo tiene la capacidad de unirse, incluso en tiempos difíciles, y continuar compartiendo ideas y mejores prácticas mientras conformamos nuevos lazos y mantenemos nuestras amistades de siempre. Para registrarse u obtener más información sobre los protocolos de seguridad que estamos implementando para el evento, ingrese en acfchefs.org.

Hablando de entablar lazos, si aún no lo han hecho, los invito a que visiten Chef's Table, el nuevo foro de la comunidad en línea de la ACF, que se presentó este verano. Este foro fue diseñado como un espacio privado y unido para que ustedes, nuestros miembros, puedan intercambiar perspectivas e ideas. La conectividad y la comunidad siempre han sido un componente fundamental de la membresía de ACF, pero en el mundo actual, son aún más importantes.

A medida que avanzamos, no duden en seguir comunicándose con ACF y con todos y cada uno de los miembros de la junta, incluido yo, con una llamada o un mensaje de correo electrónico. Nos tomamos muy en serio nuestras posiciones como miembros de la junta porque sabemos que ustedes nos eligieron para liderar y servirles. Este es el momento para un nuevo comienzo. Juntos, sigamos siendo agentes del progreso, no solo para nuestra organización, sino para la industria en general.

Thomas “Tom” Macrina, CEC, CCA, AAC Presidente Nacional American Culinary Federation

WEARECHEFS .COM 5

What’s Cooking on We Are Chefs

The latest stories recap powerful sessions from the first-ever ACF Virtual Convention, “Around the World in 80 Plates,” held Aug. 3 to 5. To view all recorded videos, visit bit.ly/acfvirtcon.

State of the Culinary Industry

This wildly popular session during the virtual convention featured four ACF members with Certified Master Chef (CMC) credentials talking about COVID-19’s impact on the culinary industry in terms of jobs, operations, technology and more, and what we can do to move forward as a team to recover and grow. Moderated by James Corwell, executive chef and innovations officer at Ocean Hugger Foods, the panel also included commentary from Chefs Joseph Leonardi, Shawn Loving and Russell Scott.

Farming During COVID-19

Two sessions offered a look at farming from a chef’s point of view. “Chef and Farmer; Agriculture from a Culinarian’s Perspective,” hosted by Farmer Lee Jones, co-owner of The Chef’s Garden and The Culinary Vegetable Institute in Milan, Ohio, talked about the ways he’s had to shift gears as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, and how chefs can best work with him and other small farmers to maximize creative uses for fresh ingredients. In “Exploring World Flavors; Inspired Grains,” hosted by Chef Jay Ziobrowski, CEC, president of ACF Chefs of Charlotte Inc., talked about how to incorporate different grains in dishes to reduce their carbon footprint and up the nutritional and flavor components.

A “Wok-ing Tour”

Celebrity Chef Martin Yan, host of the popular, now-classic “Yan Can Cook, So Can You” TV show, talked about how to select your wok and the different ways to use this workhorse — not just in Chinese cooking, but for steaming, sautéing and stir-frying all types of ingredients.

Perfecting Plating and “Phonetography”

ACF Chef Scott Craig of Myers Park Country Club in Charlotte, North Carolina, provided tips on how to prepare winning plates during competitions. In “Picture Perfect Plates; Food Phonetography 101,” professional food and beverage photographer Leigh Loftus illustrated how chefs can take photos of their food on their cell phone that more accurately represent the culinary artistry of their dishes.

Thoughts and Recipes from Jacques Pépin

Legendary chef Jacques Pépin offered some inspiration to chefs here and abroad during his convention keynote speech. He also demonstrated a few dishes. We’ve posted recipes from two of his demos: Baked Salmon with Braised Belgian Endive, and Roast Breast of Veal with Caramelized Root Vegetables and Natural Au Jus.

Follow the ACF on your favorite social media platforms:

@acfchefs

@acfchefs

@acf_chefs

@acfchefs

American Culinary Federation

Twitter question of the month:

What is the most dramatic change you have made to your kitchen setup as a result of COVID-19?

Tweet us your answer using the hashtag #ACFasks and we’ll retweet our favorites.

The Culinary Insider, the ACF’s bi-weekly newsletter, offers timely information about events, certification, member discounts, the newest blog posts, competitions, contests and much more. Sign up at acfchefs.org/tci

Sure, digital is environmentally friendly...

A digital subscription to NCR is included with ACF membership, but members can now get a one-year print subscription for just $25! Visit acfchefs.org/ncr to get yours today.

6 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | On the Line |

but paper smells better.

share generously. eat naturally. live deliciously.

When you choose Prosciutto di San Daniele PDO, Grana Padano PDO and Prosciutto di Parma PDO, you show a passion for the Italian way of life that includes incomparably delicious, natural food that’s never mass-produced or processed. Each of these products carries the Protected Designation of Origin seal, the European Union’s guarantee of quality and authenticity, so you know they are from a specific geographical region in Italy and are created using traditional techniques that have set the standard of culinary excellence for generations. Learn more about these icons of European taste at iconsofeuropeantaste.eu

THE EUROPEAN UNION SUPPORTS

CAMPAIGNS THAT PROMOTE HIGH QUALITY AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS.

CAMPAIGN FINANCED WITH AID FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION.

The content of this promotion campaign represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission and the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) do not accept any responsibility for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

CAMPAIGN FINANCED WITH AID FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION.

The content of this promotion campaign represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission and the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) do not accept any responsibility for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

NEWS BITES

ACF Launches Chef’s Table

ACF is pleased to announce the launch of Chef’s Table, a new online forum dedicated to you, our members. In the first six weeks since the launch, more than 1,000 members logged in and exchanged more than 400 topics and replies. On average, each post generates about six replies, which outshines the average of just two replies per post for most associations, according to data from Higher Logic, the platform provider with which ACF has partnered to develop the forum.

“This shows just how engaged and collaborative our community truly is,” says Joseph Syrowick, director of membership development for the ACF. “The key is community, especially during these challenging times, when we’re not traveling or seeing each other in person as much. Associations are and should be of, for and by the members, and Chef’s Table allows our members just that — [a way] to facilitate their own dialogue and discussion.”

Hot topics so far have centered around the coronavirus and its effects on the culinary profession; ACF certifications; the ways culinary instructors are preparing for the new school year in a pandemic; the status of upcoming food shows; securing the best Personal Protective Equipment for culinarians; mental health and wellness; and diversity and inclusion in our kitchens.

Chef’s Table “is also fast becoming a clearinghouse for ACF Chapters, as a number of our 170 chapters are announcing their upcoming virtual chapter meetings using the forum, and they are making these meetings available to all ACF members, regardless of where they live,” Syrowik says.

The impetus behind launching the online community as a member benefit was to create a collaborative space that could help members have closer-knit conversations. “We’re really seeing some grassroots connections among members and chapters without [their] having to rely on or wait for meetings and events,” Syrowik says. “ACF is always looking to improve the member experience and add value. Now more than ever, community is needed among ACF members, and Chef’s Table is playing a vital role during the pandemic while members are unable to gather in person.”

To join the discussion, visit chefs-table.acfchefs.org and enter the same user ID and password you use to log into the ACF website. Forgot your login information? Call ACF Membership Team at 904-824-4468 to gain immediate access.

ACF Certification Badges: Digital. Secure. Verified.

As the premier certifying body for cooks and chefs in America, ACF remains committed to providing you with the tools to achieve your professional goals. We are pleased to announce the launch of a new way to communicate the ACF credentials you have earned in the ever-expanding online marketplace — at no cost to you!

We have partnered with Credly’s Acclaim platform to provide you with a digital version of your credentials. Digital badges can be used in email signatures or digital resumes, and on social media sites such as LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter. This digital image contains verified metadata that describes your qualifications and the processes required to earn them.

If you are ACF-certified, you will be receiving an email with additional information. If you do not receive an email by Sept. 8, 2020, please send an email to educate@acfchefs.net. Learn more about ACF’s digital badges on acfchefs.org/badges.

| News Bites | 8 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020

love proudly. eat classically. live deliciously.

When you choose Prosciutto di San Daniele PDO, Grana Padano PDO and Prosciutto di Parma PDO, you show a passion for the Italian way of life that includes incomparably delicious, natural food that’s never mass-produced or processed. Each of these products carries the Protected Designation of Origin seal, the European Union’s guarantee of quality and authenticity, so you know they are from a specific geographical region in Italy and are created using traditional techniques that have set the standard of culinary excellence for generations.

Learn more about these icons of European taste at iconsofeuropeantaste.eu

CAMPAIGN FINANCED WITH AID FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION.

THE EUROPEAN UNION SUPPORTS CAMPAIGNS THAT PROMOTE HIGH QUALITY AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS.

The content of this promotion campaign represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission and the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) do not accept any responsibility for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

CAMPAIGN FINANCED WITH AID FROM THE EUROPEAN UNION.

THE EUROPEAN UNION SUPPORTS CAMPAIGNS THAT PROMOTE HIGH QUALITY AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTS.

The content of this promotion campaign represents the views of the author only and is his/her sole responsibility. The European Commission and the Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency (CHAFEA) do not accept any responsibility for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Back to School Online Learning Bundle

Students and instructors, welcome back to school! We have the tools you need to enhance your culinary education and be successful in a virtual or hybrid learning model. Purchase our Back to School online learning bundle to receive four online, self-paced courses and one practice test to earn the ACF Certificate of Culinary Essentials. This bundle is valued at more than $700 and could be yours for only $99 for ACF members ($199 for nonmembers). It will be available until Sept. 30 from the ACF Online Learning Center at acfchefs.org/OLC. Courses included are:

• Introduction to Foodservice

• Food Prep I

• Culinary Nutrition

• Safety and Sanitation

AHF Association Partnership

ACF signed an association partnership with the Association of Healthcare Foodservice (AHF). Through this new partnership, both associations will collaborate on projects, webinars and promotion of ACF Certification, as well as aim to uplift and support all healthcare/senior-living chefs and their teams, who have been important frontline workers during the pandemic and beyond.

Special Elections

ACF ran a Special Election for Nominations and Elections Chair. We accepted Intent to Run Forms through Sept. 5, 2020. In addition, nominations have begun for positions on the ACF Board of Directors and will remain open until Dec. 1. Visit the ACF Elections page for more information and Intent to Run forms. Please note that the American Academy of Chefs election is handled separately. If you have any questions, contact elections@acfchefs.net.

ACFEF Healthy Eating Outreach Grant

American Culinary Federation Education Foundation (ACFEF), through the Chef & Child initiative, is offering ACF chefs and chapters grant funding to support nutrition outreach activities in their communities. The grant deadline is Sept. 31. Visit acfchefs.org for more information.

10 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | News Bites |

SALUT

Chef Morris Salerno was selected as ACF Texas Chef of the Year. Chef Salerno is the executive chef of Bistecca − An Italian Steakhouse, in Highland Village, Texas. He was also recently inducted into the Honorary Fellow of the American Academy of Chefs, as well as into the Circle of Honor for the Texas Chefs Association.

Chef Jennifer Denlinger, Ph.D., CCC, CHEP, of the Southeast region, was selected as ACF National Educator of the Year.

Digital. Secure. Verified.

As the premier certifying body for cooks and chefs in America, The American Culinary Federation remains committed to providing you with the tools to achieve your professional goals. We are pleased to announce the launch of a new way to communicate the ACF credentials you have earned in the ever-expanding online marketplace — at no cost to you!

ACF chapters in Florida (ACF Central Florida, Palm Beach, Mid Florida East Coast and Tampa Bay) have continued to set up distribution sites to feed families in need. Chefs from these chapters are working with Five Star Gourmet Foods and farmers in Florida to distribute 10-pound boxes of fresh fruits and vegetables.

The Atlanta Chefs Association partnered with Athena Farms to supply more than 11,200 vegetable boxes for those in need over 13 weeks this past summer. The team at the East Lake Foundation helped the ACF chapter secure a donation site at the East Lake YMCA.

WEARECHEFS .COM 11

COVID-19 AND CULINARY SCHOOLS

Chef-instructors detail their strategies for teaching with pandemic precautions. //

by Michael Costa

Fall is traditionally back-to-school season, but because of coronavirus, education in 2020 has been anything but traditional. While many K-12 schools and universities have pivoted to online learning in lieu of inperson classes, culinary schools across the country are making tough decisions about the kitchen classrooms that provide crucial hands-on experience for aspiring chefs.

“This is an applied degree, so individuals need to actually execute the techniques in order to learn them, and this should be under the guidance of a faceto-face instructor,” says Chef Michael McGreal, CEC, CCE,

Culinary Arts Department

Culinary Arts Department

Chair at Joliet Junior College, City Center Campus, in Joliet, Illinois. “Online classwork in culinary is like teaching an art appreciation class focused on theory, as opposed to an art class where students actually create. In the art appreciation class, no one becomes an artist or develops any artistic skills.”

The reality of COVID-19 means most lecture classes, like cost control or nutrition, for example, have moved to real-time, virtual environments like Zoom, Yuja and Blackboard, with some customized further through school-produced instructional videos and demos. Meanwhile, kitchen classrooms have been modified to accommodate social distancing and other pandemic precautions. We spoke with several chef-instructors to see how their plans have pivoted due to the crisis, and what changes they think might be permanent.

FEWER STUDENTS, MORE SPACE

All of the instructors we interviewed say kitchen classes have been reduced to between eight and 18 students, depending on the size of the space and what’s allowed in their state, with no partner work or group activities. At schools with a large number of students, lab time is staggered, and those not in a kitchen classroom on designated days take their courses online instead.

Because COVID-19 remains a fluid situation, some schools are preparing for an entirely at-home learning environment, if necessary. “If that happens, our students will [use] a Zoom link for class, and instructors [either] will evaluate student work visually, with review from family members, or will require a selfevaluation,” explains Chef Jennifer Denlinger, CCC®, CHEP, Culinary Management Program Department Chair at the Poinciana Campus of Valencia College in Orlando, Florida. “Recipes have also been modified so students can use equipment and supplies they have in their household. Curriculum is technique- or theorydriven, not recipe-driven, which allows for substitution of ingredients, flavors and cooking vessels.”

Anticipating a possible shutdown during fall semester, Chef Denlinger frontloaded essential lab courses for students so they can complete those classes before a possible closure. When the school actually was shut down this past spring, Denlinger and her team put together at-home kits with supplies and ingredients for about 30 students who needed kitchen work in order to graduate that semester, with students documenting their work through photos for evaluation. It’s a template she’d use again if necessary, or for students who may be quarantined at home.

“We ran to the store for boxes and other supplies we needed, assembled the kits, and then had a contactless pick-up system,” she says. “Students and their instructors were given precise information to follow, and then students turned in the assignments with photos for grading.”

12 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Management |

Chef Michael McGreal, CEC, CCE, culinary arts department chair, Joliet Junior College, Joliet, Illinois

Reconfiguring kitchens for social distancing has been a relatively simple task at some schools, because many already have spacious workstations to give students more room while they learn the basics. At Joliet Junior College, for example, only eight students during the pandemic are allowed per class, which leaves 12 feet of space between each person.

All the instructors we contacted say masks are mandatory on campus, gloves are required while handling food, and at places like Daytona State College in Daytona Beach, Florida, students must sign a waiver stating they will adhere to COVID-19 safety protocols, or risk being removed from the program. “All of our students enter the building at one designated door, where they’ll be checked in and have their temperature taken with an infrared thermometer,” says Chef Costa Magoulas, dean, School of Hospitality and Culinary Management at Daytona State. “We added the waiver this summer to coincide with our hybrid

classes — groups of nine students each, alternating kitchen days to allow for social distancing — and they have no problem with the procedures in place.”

CATALYST FOR CHANGE

Sanitation education is vital to any culinary program; HACCP, ServSafe and others are required training to ensure food safety. Now, COVID-19 has amplified that focus with a deeper emphasis on clean workstations and surrounding environments, with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for one, adding additional guidelines to its current safety protocol. Some instructors think this will help reinforce certain sanitation habits that can sometimes become lax in the kitchen.

“We have the opportunity now to improve how we clean as we go, and fix improper glove usage and improper hand washing,” Chef McGreal says. “Adhering to requirements necessary to deal with COVID-19 also has the potential to

Culinary students at Joliet Junior College College will continue to receive hands-on culinary training, but masks and social distancing are required.

dramatically impact the way students handle tools, serviceware, china, plated dishes and more.”

Chef Edward Adel, culinary instructor at Johnson County Community College in Overland Park, Kansas, adds, “The real change with coronavirus is the increased emphasis on sanitation. In our industry, this has always been important, but now we must be hyper-diligent. We sanitize surfaces before and after uses, including tables and chairs in the classroom area.”

Overall, instructors say what they teach during the pandemic ultimately needs to reflect what’s happening in the real world of restaurants, catering and professional foodservice, so students can navigate this new landscape as they enter the workforce.

“The No. 1 goal of our school’s task force has been to incorporate every learning opportunity we can to work with COVID-19 and not against it, because that learning curve will be needed for the industry,” says Chef Shawn Loving, CMC, instructor and Culinary Arts Department Chair at Schoolcraft College in Livonia, Michigan. “We’re training our students for the possibilities of what will take place in the industry, with smaller numbers of people in dining rooms, and new approaches for à la carte, modern buffets and controlled familystyle service.”

The next step for culinary instructors, and the wider education system, is to gauge when it will be OK to return to traditional teaching techniques, curriculum and classroom instruction, or whether some of the adjustments made during the pandemic are permanent. The chefs we talked to say the current changes are here to stay at least into 2021.

WEARECHEFS .COM 13

Michael Costa is the former editorial director of Hotel F&B magazine and a regular contributor to NCR

CHAPTER CLOSE-UP:

ACF Central Florida Chefs Association

Chef Joe Alfano, CEC, AAC, president // By Lynda Gail Alfano, marketing director

The American Culinary Federation’s Central Florida Chapter was established in 1973, making it one of the earliest ACF chapters in the state. With the mission of promoting the professional image of the American chef in the Central Florida area, the founders’ first goal was to support and achieve certification. Some of our chapter founders went on to be some of the first chefs to achieve the Certified Executive Chef designation. Among the early and founding members of our chapter were Chefs Keith Keogh, CEC, AAC; Gus Stamatin, CEC; Klaus Friedenreich, CMC, AAC; Johnny Rivers, CEC, AAC; and Louis Perrotte, CEC, AAC.

Orlando has long been a great location for chefs, as it is a hub for the hospitality industry, with a huge variety of theme parks, resorts, country clubs and restaurants. Chefs have found a home in the ACF CFC, and competitive involvement has always been a hallmark of our chapter. Five of our members have reached the highest honor of ACF National Chef of the Year: Chefs Russell Scott, CMC; Joe Amendola, CEPC, CCE, AAC; Klaus Friedenreich, CMC, AAC; Steve Jayson, CEC, AAC; and Reimund Pitz, CEC, CCE, AAC. In addition, two other chefs from our chapter, Chefs Steven Rujak and Andreas Proisl, CEPC, AAC, have won the highest award on the pastry side — National Pastry Chef of the Year.

An Eye on Charity

Another mission of the ACF Central Florida Chapter has always included community involvement. Our chefs aspire to be culinary leaders, and leadership begins with giving back. For 26 years, our chapter has sponsored Give Kids The World, an organization dedicated to children with critical illnesses. Kids and their families come from around the world to a special resort here in the Orlando area, Give Kids The World

Village, for the vacation of a lifetime. Every year, our chefs host a Christmas dinner at the resort, providing a holiday feast for every family there.

Over the years, our chapter has partnered with and supported many local charity organizations. Our chefs have prepared fundraising Thanksgiving dinners at Second Harvest Food Bank of Central Florida, as well as meals for victims of hurricanes and the pandemic. We participate every year in fundraisers like the Cattle Baron’s Ball, which supports the American Cancer Society; Taste! Central Florida, which supports both the Second Harvest Food Bank and the Coalition for the Homeless; and Share Our Strength, whose campaigns include No Kid Hungry.

This summer, we joined many ACF chapters in organizing massive produce giveaways to support our local community. Every Friday in July and August, Chef Bryan Frick, CEC, AAC (event chairperson) and dozens of our chapter members handed out more than 11,200 boxes of produce. By the end of the summer, we had distributed 120,000 pounds of produce to local families in need. Only a dedicated and selfless army of volunteers can make that kind of effort successful, and that army was our chapter members. Many of them have also felt the impact of the shutdowns in the form of layoffs and furloughs, but they gave selflessly. In return, our chapter used these produce giveaway events as an incentive program — they gave their time, and we gave back to them by assisting them with their ACF annual dues renewals.

Awards and Events

Our chapter is so proud to add two more national awards to our members just this year: The 2020 Chef Educator of the Year was awarded to Chef Jennifer Denlinger, Ph.D., CCC, CHEP

14 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Chapter Close-Up |

(Valencia College, Chef-Instructor and Culinary Management Department Chair), and the 2020 Hermann G. Rusch Chef’s Achievement was awarded to Chef Louis Perrotte, CEC, AAC.

For almost 26 years, our chapter has hosted the Culinary Arts Competition, a large competitive event that annually features four or more ACF-sanctioned competitions in hot food and pastry categories, with as much as $70,000 in prize money. Our competition has become a staple at the Florida Restaurant & Lodging Show, held in Orlando every year. For the past three years, we have added to our event two special competitions just for aspiring young chefs and sous chefs. The first is through a partnership with Florida ProStart in which 15 student teams from high school culinary programs throughout Florida compete for bragging rights. The other is a competition to inspire sous chefs to showcase their creations as “The Next Big Thing,” through a partnership with Scott Joseph, a local food consultant.

The appeal of Orlando has brought many conventions to our city and has given our chapter the opportunity to host this epic event many times. Chef Roger Newell, CEC, CCE, CCA, AAC, has led our volunteer team almost every time — and he’s dusting off that event binder once again, because we are on the calendar to host in 2021. We can’t wait to welcome chefs from around the country to the ACF National Convention (and to our 50/50 Raffle).

When we couldn’t gather during the shutdowns, we moved into a new communications space. We’d hosted many virtual board meetings before, but in June, we launched our first webinar, open to our members and community guests. We called it “Adapt & Thrive: Reopening into a New Normal.” And

like many of our sister chapters, we’ve learned that we can still be together in spirit, even while social distancing.

The ACF Central Florida Chapter has thrived for 47 years because of the awesome involvement of our chapter members, to whom we are thankful. Through them, we have changed with the industry. We have partnered with local companies and culinary schools. We have raised money to support everyone from culinary teams to hurricane survivors. Our chefs have risen to every leadership challenge, from competitions to mentorships. And we have so much more give. Every year brings new opportunities to grow and expand the reach of chefs in our area.

WEARECHEFS .COM 15

From left: Chefs Joe Alfano, CEC, AAC (President); Jennifer Denlinger, Ph.D., CCC, CHEP (Vice President); Terrence Tookes, CEC (Treasurer); Bob Costello (Secretary); Andreas Proisl, CEPC, AAC (Sergeant at Arms); and Bryan Frick, CEC, AAC (Immediate Past President).

"

ONLY A DEDICATED AND SELFLESS ARMY OF VOLUNTEERS CAN MAKE THAT KIND OF EFFORT SUCCESSFUL, AND THAT ARMY WAS OUR CHAPTER MEMBERS."

By Amanda Baltazar

There may be a plant-based craze going on right now, but vegan foods aren’t for everyone. Plenty of American consumers still seek meat-rich meals, which helps keep the art of butchery alive.

We checked in with some chefs to find out the trends in that world.

LESS EXPENSIVE CUTS

Americans are looking for comfort food, given all the uncertainty surrounding COVID-19, which means inexpensive cuts, says Chef Jeffrey Schlissel, president of the Palm Beach Chefs Association and an active ACF chef for more than 20 years. He has a passion for butchery and runs Bacon Cartel, an online pork resale and catering business based in Boca Raton, Florida.

One of his favorites is beef plate, which is near the flank and the brisket. “It has grain in two ways, but the fat content,

with the marbling, makes it an amazing cut,” he says, adding that he smokes the plate to make beef bacon, offering a unique spin on a classic favorite.

He also expects to see more tri-tip, shoulder clods, flat meats like skirts, chuck roll, chuck steak and offal. There’s also the butcher’s filet, which was traditionally what the butcher took home because it was the beefiest, “yummiest” cut. Also known as the hanging tender, it's located near the animal’s kidney. “It’s not the sexiest cut of meat, but it has the marbling of a filet and the beefiness of a ribeye, so it lives in the best of both worlds. I’ve ‘Szechuaned’ it with a glaze; done it with rubs; grilled it,” Chef Schlissel says.

Many chefs don’t want to cook these lesser cuts because they take so long, he says, “but the end products are phenomenal.”

16 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Main Course |

Pandemic or not, consumers are looking for more from their meat, and chefs are obliging

DRY AGING

Of the 42 menu items at Knife in Dallas, nine or 10 are dry aged. “Dry aging meat allows it to become richer, tighter and beefier,” says Chef/Owner John Tesar, who ages the meat for up to 240 days. Most popular are his ribeye and sirloin; he’s also featured short aged pork chops on the menu, which are aged up to 21 days.

Chef Tesar has been experimenting with white mold from his lox for the past six years and is hoping Knife will be the first restaurant in the country to use this natural white mold for beef. Others, he says, inoculate their steak to grow the mold, and typically buy the culture from a purveyor, rather than doing it in-house. He’s also experimenting with dry-aged foie gras, which “is quite amazing, because it concentrates the sweetness and nuttiness,” he says. “By eliminating the moisture, it leaves 100% fat, and changes the texture, allowing us to cook it several ways.”

All consumers are becoming professional diners, so dry aging is important, says Chef Marc Hennessy of Baltimore steakhouse Monarque.

“Guests are looking for an experience and a stronger flavor of steak and a better texture,” he says, noting that dry aging has gone beyond being just a fad. “It’s going to stick around.”

UNUSUAL CUTS

Since Chef Hennessy started buying whole animals, he’s finding new cuts he didn’t use before. “There’s a country-cut, bone-in filet under the sirloin, after the short loin cut,” he says. “It’s the full end of the beef tenderloin, so it’s the fattest, thickest part of it.” Each cow has just four to six of these, “so it’s a luxury cut,” he says; he charges $150 for a 20-ounce steak.

Chef Hennessy has given some of these cuts their own names, such as the “Atlas Pin Chop,” a large cut from the same area with bone and sirloin intact, which is cut after the porterhouse.

He’s also found a way to remove the entire flat iron steak, bone in, which he dry ages for more than a month. “We created a really cool steak we’d never heard of cut this way,” Chef Hennessy says. “It’s really

WEARECHEFS .COM 17

Chef Marc Hennessy (left); Chef Justin Severino (right)

soft and super tender, and has an iron-y flavor due to where it is.”

CARED-FOR MEAT

Meat that has no hormones or antibiotics, and is non-GMO and grassfed, is becoming increasingly important to America’s dining public and its chefs.

“I want things that are more wholesome for our guests,” Chef Hennessy says. And, he adds, these products have become less expensive while, at the same time, “guests are more willing to spend the money.”

At RARE Steakhouse — where, until recently, Hennessy served as executive chef — the grass-fed, local, all-natural beef products have their own menu category; that section constituted 35% to 37% of sales. During the COVID-19 shutdown, the steakhouse — which has locations in Madison, Wisconsin; Milwaukee; and Washington, D.C. — ran a butcher’s shop, and these products sold really well. “[They] never lost [their] demand. People are looking for healthier food and want to know where their food is coming from,” Chef Hennessy says.

MEAT BY THE BOX

Two years ago, Chef Justin Severino launched Salty Pork Bits, a retail charcuterie company that ships nationwide. Also the co-owner of Morcilla in Pittsburgh, Chef Severino started Salty Pork Bits as a subscription-based company; it now sells options such as Spanish, Italian or French boxes, each typically containing four salamis.

The boxes feature charcuterie, and Chef Severino, a whole-animal butcher and chef, is getting ready to add more meats like pancetta and bacon. In his repertoire are about 64 flavors of salami.

Chef Severino is most excited about his twoingredient salamis because “we take things that are beautiful when in season and do as little possible to them,” he explains. Of course, they have salt, sugar, nitrites and starter culture, which makes the salami safe, but beyond that, he likes to add just one ingredient to the meat, such as padrone pepper, smoked apple, tomato, ramps or green garlic. “We focus on trying to perfect simple dishes, which is much harder to do than a dish with many ingredients,” he says.

The products are local as much as possible, as well as seasonal. “It’s such a great representation of where we are geographically and seasonally,” Chef Severino says.

18 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Main Course |

Amanda Baltazar is a food and beverage reporter based in the soggy Pacific Northwest, who writes for and about chefs and restaurant operations.

Chef John Tesar (left); Chef Jeffrey Schlissel (right)

KNIVES OUT

One chef offers his tips for butchery knife selection and maintenance

Chef Jeffrey Schlissel, “kingpin” and owner of The Bacon Cartel in Boca Raton, Florida., relies on three knives: a good boning knife, a boning saw and a meat cleaver. He also gets a lot of use out of his cimeter, which he says is like a machete, but ribbed for slicing through fat “so it makes it easier to cut.”

The most important thing when buying a knife is to hold it, he says: “It’s about the balance and how it feels in your hand.” However, his preference is for highcarbon German steel knives, simply because that’s what he grew up with. But also, he says, with these knives, “it’s easier to maintain the edges, especially if you’re going to be whacking a lot of meat.” Chef Schlissel points out it’s not the butcher’s strength that breaks down the meat; rather, it’s gravity and the knife. “It’s about learning where those grains of meat meet — how it’s connected and how to cut the connection.”

As important as the knives: having a good steel with which to sharpen them. Chef Schlissel does a lot of sharpening, and points out that “the more force you use, the more you’re breaking the blade; the edge gets out of alignment, and using a steel brings back the alignment.” When sharpening, he says, it’s important to not grind too

much of the blade down, and it’s vital to use the right degree. Sharp knives are important, he says, because the sharper the knife, the less force you have to use; additionally, the sharper the knife, the less chance of cutting yourself.

Chef Schlissel sharpen his knives at least once a week, but typically every couple of days. “I’m constantly doing it,” he says, but warns: “You can mess them up— they become one-sided with more of an edge on one side. There’s a sweet spot.” His sharpener of choice is a wet stone, and he says he loves sharpening: “Sharpening a knife is a very Zen-like act; you become one with a knife.” He never gives his knives to professional sharpeners; he doesn’t feel the need.

For chefs just starting out, Chef Schlissel recommends buying an inexpensive knife. “Beat it up to the point where you’re going to have to sharpen it, and use that to hone your skills, rather than messing up a $100 or a $400 knife. Use that $20 knife to practice.”

Chef Schlissel takes care of his knives. He washes them every time he uses them, and when he changes what he’s cutting, to prevent cross-contamination. “Every time you open up a new package, it has a chance of having a foodborne illness,” he says. -AB

WEARECHEFS .COM 19 | On the Side |

Lean and healthy, rabbit also makes for a sustainable and versatile meat // By Rob Benes

Editor’s Note: This article was previously scheduled to appear in the March-April issue, but was moved to make room for a COVID-19 special issue. Some of the menu items may no longer be available, but the ideas and uses for rabbit remain valid. Diner interest in healthy eating combined with chefs’ ongoing quests for new ingredients have led to a resurgence in the use of rabbit.

“More chefs are realizing that rabbit is actually a sustainable protein, and when done right, tastes delicious,” says Michael Beltran, executive chef of Ariete in Coconut Grove, Florida. “I also think diners are opening up to eating what could be considered to be more of an exotic meat.”

Compared with beef, pork, lamb, turkey, veal and chicken, rabbit has the highest percentage of protein, the lowest percentage of fat and the fewest calories per pound, according to the U.S.

Department of Agriculture. Rabbit also has appeal across a multitude of markets, as Muslims, Christians, Hindus and Jews have no religious prohibitions from consuming rabbit meat.

Rabbit is a relatively inexpensive protein to source, too, with dressed and processed rabbit meat selling for between $6 and $7 per pound. “Deboning and breaking down a raw rabbit can be a bit difficult, [because] it has tiny bones,” Chef Beltran says. “It’s also much easier to use a whole rabbit [because] they’re just a few pounds, compared [with] buying a 200-pound pig.”

Rabbit can be compared to chicken as being a blank canvas, but it offers so much more. “Rabbit has a clean and mild flavor on its own, but it picks up myriad flavors easily and very well, so it’s a versatile protein for all types of cuisines,” Chef Beltran says. He menus a rabbit pâté with a compote of mamey (a tropical fruit featured in the July-August issue of NCR), grain mustard and house-made white bread.

Here are a few more examples of rabbit on menus:

• R abbit Curry by Chef Nina Compton and Levi Raines, Bywater American Bistro, New Orleans. Trimmed leg portions are seasoned with warm spices, arranged in a hotel pan and marinated for two hours, then covered with rabbit oil and cooked in a combi oven at 300-degrees F for two hours.

20 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | On the Side |

The legs are allowed to cool in the oil, then removed, vacuumsealed and reserved in the cooler until needed. The meat is eventually added to a curry made with rabbit trimmings, chicken wings, chicken drumettes, warm spices, coconut milk, ginger, turmeric, onion, habanero and brown stock. When served, the curry mixture is ladled into a bowl, jasmine white rice is spooned on the side and a cooked rabbit leg is set in the curry. The dish is garnished with toasted pecans and cilantro.

• R abbit Pappardelle by Chef Nathan Duensing, Marsh House, Nashville. Rabbit legs and bellies are seared and then braised with aromatics for two hours in brown stock. The fall-off-the-bone meat is then added to a pan of sautéed garlic, parsley, rosemary, tomato sauce and reduced braising liquid, and cooked until a loose sauce is made. Finally, cooked pappardelle and herbs are added and tossed together. The dish is garnished with Parmesan and olive oil.

• Fried Rabbit Livers by Chef Isaac Toups, Toups’ Meatery, New Orleans. Rabbit livers are marinated in sherry for 30 minutes, dipped in an egg wash, dredged in a mixture of popcorn salt, white pepper, flour and cornmeal, and then deep-fried in 350-degrees F peanut oil for two to three minutes. The livers are served warm on a bed of Romesco sauce and garnished with a chilled carrot-apple slaw.

• R abbit Loins by Chef Philip Whitmarsh, Jewel of the South, New Orleans. Confit meat of rabbit hind legs and

rabbit offal are folded into a simple chicken mousse. The mousse mixture is spread over rabbit loins, wrapped in guanciale, seared and browned in a hot pan, wrapped in cling film, and poached in simmering water for 12 minutes. The loins are topped with hot butter at the pass before serving.

WEARECHEFS .COM 21

Rob Benes is a Chicago-based food industry journalist. He can be reached at robbenes@comcast.net.

Fried rabbit livers by Chef Isaac Toups (credit: Toups' Meatery, New Orleans) (above); rabbit curry at Bywater American Bistro, New Orleans (credit: Denny Culbert) (below).

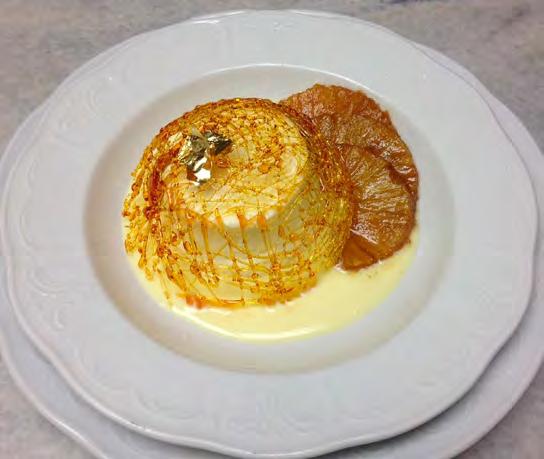

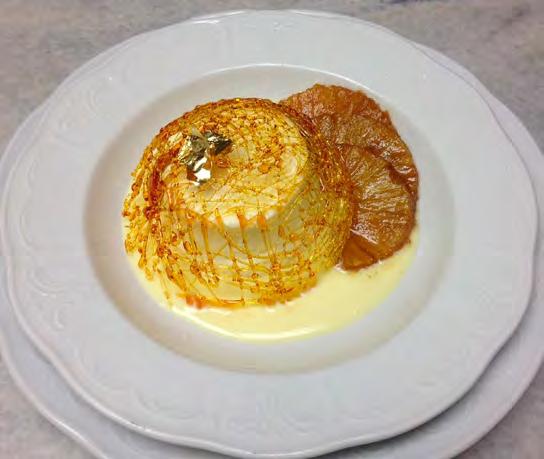

REVISITING CRÈME ANGLAISE

An English cream with a French name / By

Robert Wemischner

On the surface, with its short ingredient list, crème anglaise does not seem very promising as an element of a sophisticated dessert. At its base, it is only a mixture of liquid dairy (milk or cream, or a combination of the two), egg yolks, sugar and a flavoring of choice. That’s it.

Yet it is a classic for a reason. Every pastry chef worth his or her sugar calls upon this perfectly balanced combination of ingredients for use in many ways, whether as a plating sauce or as a base for mousse, ice cream, Bavarian cream, crème brûlée and crémeux (a sauce that’s set with chocolate or gelatin, or both). When properly made, this mother sauce of the sweet kitchen lends richness, a sense of luxury and a pleasant mouthfeel to just about any dessert.

“Because it’s so versatile, it’s a classic,” says Chef Natasha Capper, executive pastry chef at Piedmont Driving Club in Atlanta, who calls it a workhorse in the pastry kitchen. “When making crème anglaise, I like to think of it as a marathon, not a race. The mixture is far more forgiving when cooked over a mild flame and attended to constantly; never walk away from it during that process. Low and slow is the way to go. When done, the mixture should reach about 175-degrees F.”

Shirley O. Corriher echoes Capper’s sentiments, writing in one of her books, “BakeWise,” “Stirred custards without starch, like crème anglaise ... require very low heat and constant stirring.” She sums things up by looking at the science behind the sauce, noting the making of crème anglaise involves cooking liquid dairy with egg yolks (about 25% of the weight of the dairy) and some sugar (about 15% to 20% of the dairy). Beyond lending sweetness, the sugar slows down the bonding of the protein in the eggs, yielding a mixture with the consistency of heavy cream at serving temperature. It should not taste eggy; that’s usually an indication that the mixture was cooked at too high a temperature.

22 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Pastry |

Andy Chlebana, author of “The Advanced Art of Baking and Pastry,” and a chef-instructor at Joliet Junior College in Joliet, Illinois, says about crème anglaise: “It’s not a set-it-and-forget-it kind of preparation. When I teach it, it’s not only about the sauce; it’s also about the steps to a setting up a complete mise en place, [because] timing is everything once you begin the process of cooking any egg-based preparation.”

Chef Chlebana recommends cooking the mixture to 175-degrees F and says that stirring with a heatproof silicon spatula, rather than aerating the mixture with a whisk when it’s being cooked in a saucepan, leads to the best result. Taking the mixture once step further, Chlebana also likes to process the sauce using an immersion blender to create a light foam as a final fillip on a plated dessert.

Chef Geoffrey Blount, program chair for baking and pastry at the International Culinary Institute of Myrtle Beach in South Carolina, challenges his students by asking them to create five things with a well-made crème anglaise. “After a couple of times using a thermometer when cooking the mixture, I insist that

students rely on visual cues to indicate when the sauce is done,” he says. In addition to creating a crémeux that’s jellified with chocolate, he’s also made an Orange Dreamsicle Bavarian cream in which the crème anglaise is set with gelatin and the mixture is lightened with whipped cream.

Harking back to an oldie but goodie, Blount also enthuses about oeufs à la neige (snow eggs). In this no-waste classic, all of the egg is used. Ingenious and thrifty, the dessert features egg yolks for the crème anglaise, which serves as the pool upon which milk-poached, egg white-based meringues float. Classically, a bit of golden caramel and toasted almonds finish the ensemble.

Chef Michael Zebrowski, an instructor at the Culinary Institute of America and co-author of “The Pastry Chef’s Little Black Book,” uses a soda siphon with CO2 chargers to aerate a finished crème anglaise. “I also love to make a semifreddo — which merges the chilled custard sauce with meringue and whipped cream in a frozen molded dessert — flavoring it with everything from pureed, sweetened chestnuts to Armagnac, a French brandy; Grand Marnier; or a croquant of hazelnut and almond,” he adds.

With its quartet of ingredients each playing an important role, crème anglaise is a symphony of flavor and texture. Today, as we reach for comforting classics in a time when everything old seems new again, consider reconsidering this sauce as a versatile addition to any pastry pantry.

WEARECHEFS .COM 23

Robert Wemischner is a longtime instructor of professional baking at Los Angeles Trade Technical College and the author of four books, including “The Dessert Architect.”

Apple cider cake with cranberries and crème anglaise by Chef Natasha Capper, Piedmont Driving Club, Atlanta (opposite); floating island (flan) with caramel and crème anglaise by Chef Capper (left); crème anglaise-based hazelnut semifreddo with flourless chocolate cake, burnt orange sauce, blood orange and kumquat confit by Chef Michael Zebrowski, Culinary Institute of America, Hyde Park, New York (right)

Classical

Poulet sauté a la Bourguignonne, which means “as prepared in Burgundy,” is perhaps a lesser-known French dish than its counterpart, boeuf a la Bourguignonne. Prepared with chicken instead of beef, the dish features the same rich pan sauce — with extra tang, thanks to the use of wine versus stock as the base — while sautéed onions, mushrooms and bacon build flavor and texture. The original recipe for this classic dish can be found in Auguste Escoffier’s “The Complete Guide to Modern Cookery.” The bacon, onions and mushrooms cook in butter until browned, then are set aside while whole chicken pieces sear in the rendered fat before roasting in a 350-degrees F oven to finish cooking. Meanwhile, fat is drained from the pan, and red wine and crushed garlic are added to deglaze. Butter, mixed with flour for a beurre manié, is whisked in to thicken. Classic pairings include sauteed spinach, herbed fingerling potatoes and roasted cauliflower.

24 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Classical vs. Modern |

Modern

Chef J. Kevin Walker, CMC, executive chef of Ansley Golf Club in Atlanta, developed the modern rendition for poulet sauté a la Bourguignonne by creating a pavé that combines chicken breast cooked sous vide with porcini powder, and a wild mushroom mousseline, with applewood bacon slices lining the bottom. The pavé is served alongside chicken leg croquettes, a bacon-mushroom ragout and butternut squash two ways: pavé-style with ginger and baking spices, and simply roasted. A touch of bright-green, silken broccoli purée, pickled red pearl onions, and a simple garnish sauce made with reserved braising liquid emulsified with butter add pops of color. When Chef Walker plates a dish, he remembers something mentor and Chef Ferdinand Metz, CMC, told him: “Always look to see what you can take away from the plate to make it better.” For Chef Walker, the challenge with this dish was finding the balance between keeping the integrity of the ingredients while still creating a contemporary look. “Doing something simply is much harder than building it up,” he says.

See the classical and modern recipes as well as more photos at wearechefs.com.

WEARECHEFS .COM 25

26 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020

From Brazilian moqueca to Venezuelan fosforera, the foods and flavors from this continent hit all five senses //

By Suzanne Hall

By Suzanne Hall

WEARECHEFS .COM 27

With 6.89 million square miles and approximately 429 million people spread over 12 countries, South America is a culinary gold mine, with a wealth of native ingredients. How they are used, of course, depends on the geography, history and people of each country. The cooking of South America is a cornucopia of distinctive dishes ranging from grilled reineta, a firm, mild fish popular in Chile, to chimichurri, the go-to condiment of Argentina, while ceviche, a dish of citrus-marinated raw seafood, has variations throughout the continent.

Although many South American dishes are unfamiliar to American diners, they are becoming better known. “South America is such a big continent, with so many flavors, that it will keep growing in popularity in the U.S. throughout the next years,” says Venezuelan native Chef David Zamudio, executive sous chef at Baltimore’s Alma Cocina Latina, a restaurant specializing in the dishes of Venezuela.

Brazilian Chef Manoella Buffara agrees. She is the owner of Manu, a small tasting-menu restaurant in Curitiba, Brazil, and Ella Brasileira, a much larger and more casual restaurant in New York City. “South American ingredients are different. People like to try new flavors,” she says.

The earliest inhabitants of South America provided the inspiration and backdrop for the region’s cooking, but immigrants from around the world have added their own flavors and techniques — for example, lasagna and pizza sometimes appear on restaurant menus. Another example is pastei, a type of chicken pot pie that Jewish settlers brought to Suriname, while walnutand-raisin fried rice and Chinese pepper steak are on the menu at Ñaño, an Ecuadorian restaurant in New York City owned by Chef Abel Castro. “We add some ingredients like cilantro and garlic to the rice,” he says, to give the dishes Ecuadorian flavor.

Each group of settlers brought their own special flavors to South America, but South American cuisine has always focused mainly on what the land produces.

28 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | South America |

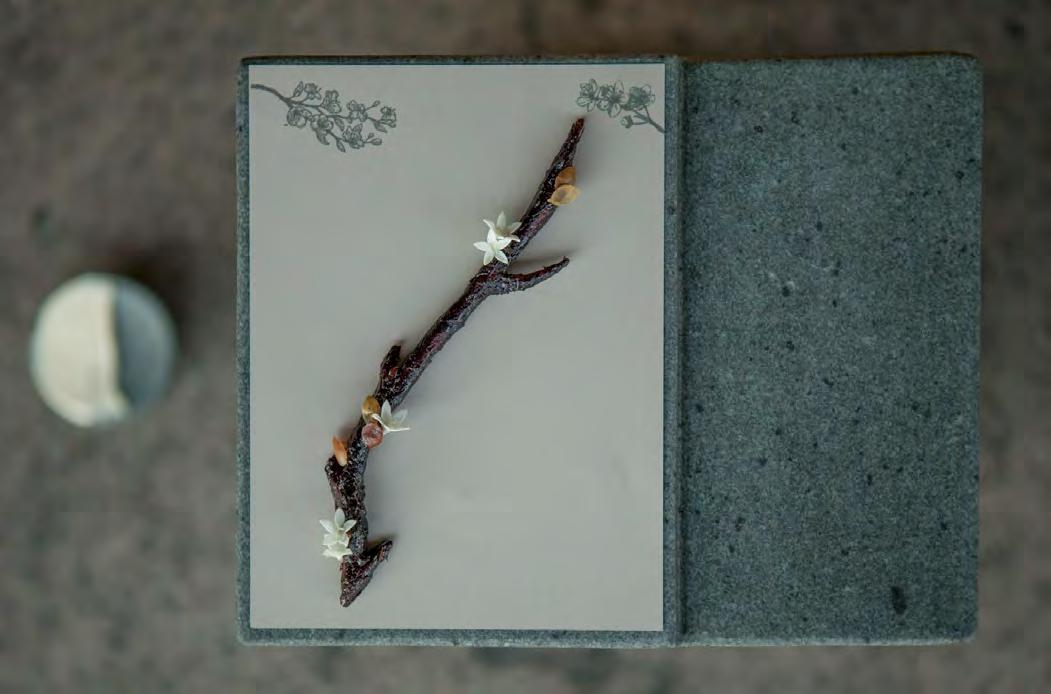

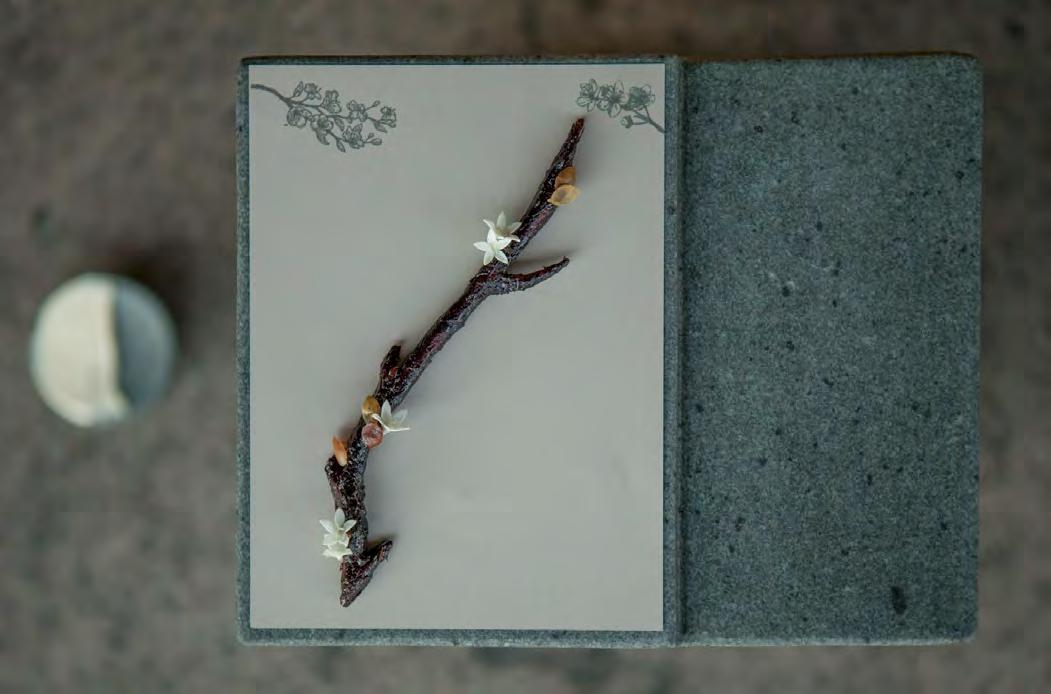

Cold pulmay (soup) of rhubarb, copihue (Chile's national flower) and wild fruit candies (previous spread); duck aged in beeswax and finished on coals with plum leaves at Boragó in Santiago, Chile (top); ceviche with mussels, fish and shrimp, served with plantain chips and Ecuadorian lager at Ñaño in New York City (bottom); Coated pork and prawns at Manu in Brazil (credit: Rubens Kato) (opposite)

From Sweet Corn to Spicy Chiles

Cultivated in South America for more than 5,000 years, corn is possibly the continent’s biggest food contribution to the rest of the world. Arepas, a Venezuelan favorite, are corn cakes stuffed with a variety of fillings. “You can fill an arepa with any ingredient you like — meat, cheese or vegetables,” Chef Zamudio says. He offers them with four different fillings. “They are so adaptable and can be a good option for vegan and vegetarian customers.”

Potatoes come in hundreds of varieties and are fried, mashed, freeze dried, baked, and combined with sauces.

“In Chile, we have more than 400 varieties,” says Chef Rodolfo Guzman, owner of Boragó in Santiago, Chile. He makes milcao, a potato bread, which he serves it with pebre, a sauce of chopped tomatoes, onions, coriander, vinegar,

salt and yellow chiles. Similarly, at Ñaño, potato chowder and potato patties filled with cheese are on the menu.

Sweet and hot peppers are South America’s most important seasoning ingredient. Aji dulce is sweet pepper sauce. Aji amarillo is a spicy yellow sauce for roasted chicken, vegetables, fries and fried yuca. The aji amarillo chile pepper is a staple in Peruvian cooking; a popular salad served at Alma Latina Cocina features chopped kale, fried egg and spicy honey, with a crispy garlic, aji amarillo and coconut dressing. “It’s very powerful,” Chef Zamudio says.

Tropical fruits like avocado, passion fruit, coconut, mango and dozens more are used in desserts as well as savory dishes and salads; Alma Cocina Latina serves guasacaca, a creamy avocado and garlic sauce, with dishes like arepas. The No. 1 seller at Ñaño is seco de chivo,

WEARECHEFS .COM 29

or goat stewed in naranjilla, a tropical citrus fruit resembling a cross between a pineapple and a lemon with a distinctive green juice.

Root vegetables like yuca, manioc and cassava are ground, dried and roasted to make myriad South American dishes. In southern Brazil, home to Manu, tutu de feijão (a paste of beans and cassava flour) is a popular dish, while Alma Cocina Latina offers yuca fries and a crispy cassava bread.

Proteins from Land and Sea

While not as large a producer as Argentina and Brazil, Venezuela produces more than enough beef to supply the country. Beef dishes include

some familiar ones, like the 18-ounce USDA-prime ribeye Chef Zamudio serves with grilled seasonal chimichurri vegetables, micro greens and merkén, a Chilean spice blend combining spicy ají cacho de cabra, cumin, coriander and salt. Churrasco, the Portuguese

30 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | South America |

and Spanish word for grilled meat, is a staple in the cuisines of Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, and is becoming increasingly popular in the U.S.

Because it’s bordered by the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, fish and seafood have long been used in South American cooking. Shrimp and other foods from the sea are widely featured in the cuisine of Suriname; Long Yard beans with dried shrimp and télo (fried cassava) with cod are two traditional dishes. Chef Buffara uses everything from sea urchins to oysters, grilled and smoked leeks, mussels, and raw fish with plantains in various dishes throughout her menu. “In northern Brazil, they make a stew with fish or shrimp and vegetables,” she says. “It’s called moqueca , and [is] made in a ceramic pot.”

Chef Castro offers seafood cazuela, a combination of fish and shrimp with peanut sauce, on his menu. Encebollado de albacora, a tuna soup with yuca, herbs and spices topped with pickled onions, is another option.

WEARECHEFS .COM 31

Pork fried rice at Ñaño in New York City (opposite); Mullet roe, papaya and pickled onions; quail egg, maté herb bernaise and tonic beans; seaweed, yogurt and mushroom with lettuce and pork fat at Manu in Brazil (credit: Rubens Kato) (clockwise from left)

The food that chefs prepare at Ñaño and other South American restaurants in the U.S. and in their native countries generally use traditional recipes, but feature each chef’s personal touch. “We cook regional dishes that are only cooked in Chile using the flavors of the land, but we cook them with originality,” Chef Guzman explains. “Originality and welldone dishes are what’s important.”

Menuing Smart and Thoughtful Presentations

At Manu in Brazil, Chef Buffara prepares dishes with traditional techniques using local ingredients; likewise, for Ella Brasileira in New York, she has adapted her recipes to use ingredients available there. Because many Brazilian dishes are cooked over fire, she has a large wood-burning grill

in the center of her open kitchen. Some, but not all, of Chef Zamudio’s dishes are derived from traditional Venezuelan recipes. “We put our own twist on them to make them our own,” he says, noting his contemporary style is very different from traditional Venezuelan cooking.

The cuisines of some South American countries are more familiar to U.S. diners than others; for example, more and more cities are home to Brazilian churrascaria, which specialize in grilled meats. “Colombian food is very popular in New York, but Ecuadorean food is very new to some,” Chef Castro says. To help his non-Ecuadorian customers feel more comfortable, each dish on the menu is described in detail.

Chef Zamudio is careful to present and name dishes in a way familiar to Americans. He makes a Venezuelan

32 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | South America |

soup called fosforera that initially, not many of his American customers wanted to try. “We then decided to change the name to ‘Latin ramen,’ even though it is actually not a ramen; then more people chose it off the menu,” he says. “How things are presented is very important.”

South American chefs want to believe, and do believe, that as their foods become more familiar to diners in the U.S., their North American colleagues will begin to create their own adaptations to fit into their individual menus. A variety of Venezuelan arepas would be a good place to start.

Chef Guzman believes the aforementioned milcao and pebre is another. Regardless of the flavors, dishes and ingredients you choose, given the size and diversity of the region, the opportunities for experimenting with South American cuisine are nearly endless.

South America’s National Dishes

A national dish, in countries that have one, reflects a country’s culinary and cultural identity. These are the national dishes (always subject to argument) of South America.

Argentina – A selection of meats, called asados are grilled on a parrilla (large grill) and can include steaks, ribs, chorizo, mollejas (sweetbreads), chinchulínes (chitterlings) and morcilla (blood sausage).

Bolivia – Two national dishes are recognized. One is picante de pollo (chicken in a spicy sauce). The other is salteñas (savory pastries filled with beef, pork, or chicken with a sauce, and sometimes vegetables).

Brazil – Portuguese in origin, feijoada is a comforting black bean stew with beef and pork.

Chile – Curanto, a popular party food, is a stew of meat, seafood and vegetables, and anything else available.

Colombia – A feast more than a dish, bandeja paisa includes rice, plantains, arepas (corn cakes), avocado, minced meat, chorizo, black sausage, fried pork rind and a fried egg.

Ecuador – Some may disagree, but the official national dish of Ecuador is encebollado, a fish stew with onion, fresh tomato and spices such as pepper or coriander leaves.

Guyana – Authentic pepperpot is a stew of beef, pig trotter, salt and cassareep, a thick brown syrup made from juice of grated cassava, sugar and spices.

Paraguay – Sopa Paraguaya is a cornbread of cornmeal, eggs, lard or butter, fresh cheese, and sometimes onions.

Peru – Ceviche in Peru is raw fish (often white sea bass) with limes, mixed with onions and hot pepper. It’s served with sweet potato and cancha (toasted corn kernels).

Suriname – Of Jewish origin, the dish called pom’s main ingredient is pomtajer, a local root vegetable baked with chicken and citrus juice.

Uruguay – Chivito is a sandwich of sliced beef with mozzarella, tomatoes, mayonnaise, black or green olives, and often bacon, fried or hard-boiled eggs, and ham.

Venezuela – Pabellón criollo combines the cuisine of indigenous peoples, Europeans and Africans. It’s made from stewed and shredded meat with rice, black beans, banana and corn.

WEARECHEFS .COM 33

Suzanne Hall covers food, wine and travel from her home on Possum Creek in Tennessee. She has been a regular contributor to ACF publications for many years.

A snack made from a twig dried plums, topped with edible flowers and sweetsavory gum-paste leaves at Manu in Brazil (credit: Rubens Kato) (opposite); Chicken stew at Ñaño in New York City (above)

WILL CORONAVIRUS BE THE GREAT CULINARY EQUALIZER?

by Chef Jennifer Hill Booker

In March, the COVID-19 virus had gained a solid foothold in the U.S. By April, the threat had become a full-blown pandemic. Its presence was felt across all corners of the foodservice industry; for restaurant owners and employees, the effects were particularly devastating.

One by one, independently owned restaurants, as well as those owned by huge restaurant groups, began closing their doors. After the first round of state-mandated restrictions and stay-at-home orders, more than 26,000 restaurants had closed, according to data from Yelp, leaving those still open scrambling to find ways to be health compliant, but also profitable. By July, almost 16,000 restaurants had permanently closed, with more shutting their doors daily.

Call me an optimist, but I believe the restaurant industry will survive the coronavirus pandemic. But even an optimist has to admit the restaurant industry will be forever changed. In particular, how we dine, and who owns and operates these establishments, will no longer look like it did before March. I must say I don’t believe that’s necessarily a bad thing.

COVID-19: The Great Disrupter

In the future of foodservice, the pre-COVID-19 restaurant model will be a thing of the past. Gone will be the hierarchies of who decides what acceptable restaurant food is, who gets the best chef and the most prestigious food awards, and more importantly, who gets the financing desperately needed to open and operate a viable foodservice operation.

Although people of all nationalities and backgrounds can be found in restaurants across the country in both the front and back of the house, racial and gender disparity is nothing new in the foodservice industry. One has come to expect that the ownership and faces of a restaurant are seldom the same people cooking that food. I believe that the coronavirus is changing that.

34 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Chef-to-Chef |

COVID-19 has closed tens of thousands of restaurants without regard to who owns them, hinting that big restaurants that spend hundreds of thousands — even millions — on a traditional dining concept may be a thing of the past. Perhaps restaurants designed on a smaller scale that can offer a mixed in-house and off-premise dining experience are the future.

Many of the restaurants currently open were either able to pivot to the emerging restaurant model of carryout, delivery and/or grab-and-go, or applied existing elements of this model to their current concepts. There are a couple of interesting points to unpack with this new restaurant model, the most thought-provoking being that this model is not new at all.

This style of service has been around for as long as there have been restaurants, but usually in poor neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color. In Mississippi, where I grew up, and in Michigan, New York, Florida and Oklahoma, where I have lived, many of our neighborhood “restaurants” were walk-ups, which are now being marketed as pick-ups. You called in your order, or you walked up to place it — usually through a window — and took your meal with you to eat elsewhere. Sometimes you could get limited grocery or pre-packaged items. Delivery, if available, was limited, and any seating was usually very sparse and/or outdoors.

Another interesting point is these walk-ups were never considered real restaurants — not necessarily because of where they were located, or even because of what was being served, but more pointedly because they did not fit into the established models of service and ownership.

I see the coronavirus creating new business models for all people. Due to a shift in where and how we eat, the culinary landscape will be forever changed. Restaurants will become less about ego and status, and more about longevity and building a community. In a sense, this pandemic is acting as the great culinary equalizer, creating a level playing field where everyone with the talent and tenacity to open a restaurant can do so.

WEARECHEFS .COM 35

"CALL ME AN OPTIMIST, BUT I BELIEVE THE RESTAURANT INDUSTRY WILL SURVIVE THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC."

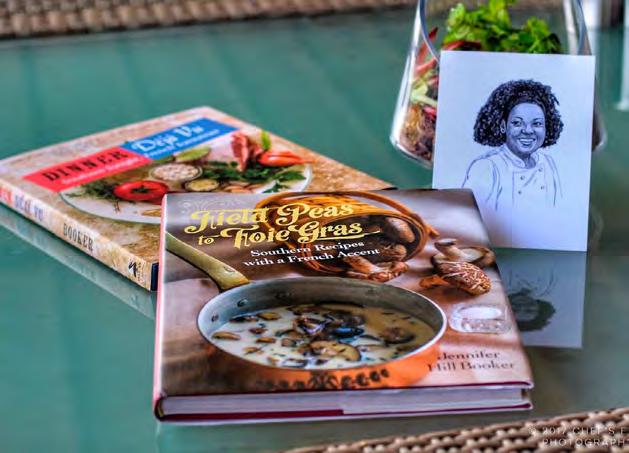

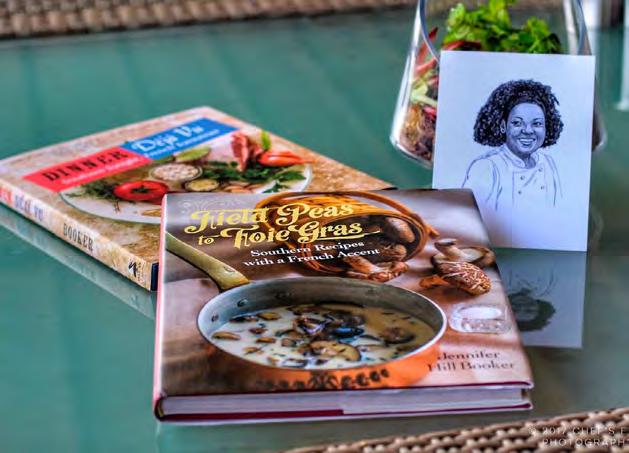

Chef Jennifer Hill Booker is a culinary consultant and author of “Dinner Déjà Vu: Southern Tonight, French Tomorrow” and “Field Peas to Foie Gras: Southern Recipes with a French Accent,” and she released her newest kitchen resource, “Cookcentric Cookbook Journals,” this year. Learn more at ChefJenniferHillBooker.com.

MISSISSIPPI SEAFOOD

Mississippi chefs highlight the state’s fresh—and healthful—catches in dishes ranging from shrimp scampi to crab Benedict.

By Liz Barrett Foster

By Liz Barrett Foster

36 NCR | SEP TEMBER/OCTOBER 2020 | Health |