ACROPOLIS

ART & ART HISTORY JOURNAL GOLD Fall 2022

Gold

Editors:

Emma Capaldi

K’Vahzsa Roberts

Staff:

Elizabeth Brady

Lauren Nash

Emma Capaldi

Aurora Noacco

Lulu Griffin

Guiliana Angotti

Renny McFadin

Diego Medal

Sierra Manja

K’Vahzsa Roberts

1

Letter from the Editors

For our Fall 2022 issue, we wanted to focus on the legacy of gold within visual art and its current influence. As a medium of luxury, gold has a long history of being utilized by artists to explore images of posterity, social hierarchies, and, of course, beauty. The written pieces in this issue of Acropolis seek to unpack this relationship between gold and its status as a universal symbol of power and strength.

By highlighting works that exhibit and exploit these qualities, we hope to contextualize the enduring impact gold has on the artist and its glorification. Materializing in a variety of forms, our staff has researched the use of gold through the years, from fifteenth century traditional oil painting to contemporary performance art. As William and Mary students, we invite further interpretations of these pieces and their relevance to the everchanging landscape of visual art.

Emma and K’Vahzsa

2

gold (n.)

a yellow precious metal, the chemical element of atomic number 79, used especially in jewelry and decoration and to guarantee the value of currencies

3

Art Poetry

4

CONTENTS

6 ... “The Offer” by Amanda Hinkle (Graduate Student)

[Paired with Forget me not (1901), Arthur Hughes]

8 ... “fools gold” by Faith Stilwell (Class of 2024)

[Paired with City Landscape (1955), Joan Mitchell]

5

6

by Amanda Hinkle

My Lover’s eyes are flames of fire

His hair is waving gold

He reaches His hand in the midnight hour

Grasping me to hold. In darkest night when straits are dire And times are drear and cold

He calls to me, my heart to power

“I’ll show you paths of gold.”

“These paths you’ll walk and never tire, Hear my words foretold, I’ll be with you every hour, E’en as the world grows old.”

“Don’t fear,” He said, “this earthly mire, Where all decays and molds, But trust in me, your strong tower Who ever makes you bold.”

My heart did leap with rare desire And reaching, I took hold Of all He offered in that hour –To walk in paths of gold.

Image Caption:

Arthur Hughes. Forget me not, 1901, Bonhams, oil on canvas, https://images1.bonhams.com/image?src=Images/live/2005-05/06/7080161-5-1.jp-

g&width=640&height=480&autosizefit=1.

7

The Offer

8

fools gold, a portrait in torment and apparitions

by Faith Stilwell

is this emptiness all there is? just a cavern between your lungs, an aching, polluted accordion singing for the ink blot streets, for the doctor smoking between shifts, for the woman with the newspaper face and all the divorcees rushing to make their next business meeting.

unending billy joel ballads, all of us, hearts pinned and stitched and framed so one day they can be splayed, wings on the wall, boxed and branded to celebrate the absence of decay, with an advertisement instead of a name: a coupon found on the posters for broadway which plaster the watermarked cobble stone sides of a fabled cosmic railway.

Is everything only a stop, and each and every one of all of all of us—just standing with the slouch of our predecessor who got their turn in this space, watered coffee and broken screen in hand, waiting on tip toes, before the last train?

I can’t say I don’t think I’m always in the wrong but the dreams she told me to discard keep me rooted in place.

9

is the world nothing but one theme to the next, until one day you’re big enough old enough broke enough to give up, to forget it and them and let the postponed neural rupture, of what was once your best trait, light the way?

are my shopping receipt prescriptions tickets to the show, or just a voucher to get into the lobby? where it’s all just doors and doors and doors, choices stacked on choices, all laid out for the walking diagnosis to make.

and then, how to get out, get through? haunted by red neon, always teasing your vision, phosphorescent e-x-i-t to titil- and po-st-u-late your brain, make you contemplate the drop, the fall to go back to Hell, from whence you came.

So, there’s smashing glass, blood for knuckles, knuckles for tricking hunger pains. burning incense, prostrating to a god you forgot, (bought out sold out hold out) and then, there’s the mephistopheles at the center when your eyes are your ears; you’ve grown ten feet tall, ten feet wide, and your fingers ripple froth and foam ocean waves rushing to mirror cliffs, and the steam rises, becomes your lips, and never in your life, has the prick of molten ichor to and from your veins felt so guiltless, so free of internal anguish.

10

Because maybe it really is the only fucking way to see the play— maybe it really is the only dash of yellow left on the platform to the subway, (and goddammit you already promised, your mother and your imagined lover and the shade of yourself that’s ballerina pink and westenra red and the color of a particular, penalizing bruise, that it’s something you could-can-would (should) do).

And then, when you get there, your so coveted box seat, is it all you hoped you would be? Or are you just another Archer, aiming for a dream, landing on a bench, refusing even a glimpse of the painted vapor face serenading from the paris balcony… when you finally must see, that the hoarded reality of your pre-sleep ponderings, your precious train-car lulled half-wishings, your vienna with eyes alight with love for you, has always been better than the hallucination you’re now living.

Will your pockets be lined with fool’s gold or teeth, do you think, when you finally reach that far off kaleidoscopic crystal sea, self-sustaining mirage made for coping, only to see the woman slurring through her soliloquy is far less magical than you always thought she’d be?

And by then, will you even have the lines you practiced, to show you belong, oh Romeo? Or just the last breath of your practical practical life,

11

exhaling on the worst beat?

“thou art…pale and sick with griefwait no, let me do it again—” can you face the darkness, when the sun never rises, and the moon thus shunned turns against you?

Is this the answer—the result you so stored up in heaven for? will fulfillment finally find you, amongst the coat-tails of the elite, whispering behind fans they didn’t make, about who so and so is sitting next you, taking gambles between summer fling, or spring wedding? Concerning themselves with the marriage cutlery; “Darling, do you prefer the Eggshell, Buttercream, Ivory, or Translucent Cotton Candy?” (if only you’d listened to your mother, you’d know what it all means).

Then when it’s over, will you be on the stage, a player in a play in a world of playing plays all day? Puck or Prospero, do you think, will be the culmination of everything you delayed in order to finally be?

Will they point to this, the lowest dip of Fortuna’s scales, As proof that you just don’t fit, certainly not so high in the glittery star-studded sky, Oscar and Wilde, with your ineptitude?

And when all your garments are golden silk, and your hair is spun of straw, and your eyes are mad and broken, photographed at the mall will you find yourself with a single sheet,

12

reciting dreams to the same old, uninterested street?

Image Caption: Joan Mitchell. City Landscape, 1955, Art Institute Chicago, oil on linen, https:// www.joanmitchellfoundation.org/uploads/artwork/mitchell/_1200x630_crop_ center-center_82_none/0006-1955-City_Landscape-Joan-Mitchell.jpg?mtime=1597164646.

13

Art Historical Writing

14

CONTENTS

16 ... All That Glitters: Schiaparelli Spring/Summer 2022 by Elizabeth Brady (Class of 2025)

19 ... Lucretia’s Golden Values by Lauren Nash (Class of 2026)

23 ... Projection of Public Image: Analyzing the Functionality of a Gold Aureus of Augustus by Emma Capaldi (Class of 2023)

27 ... Byzantine Jewellry: Was Jewellry considered upper class good? by Aurora Noacco (Class of 2023)

29 ... The Gilded Age: What’s Looming Beneath by Lulu Griffin (Class of 2025)

32 ... Gold to the Extreme: Jeff Koons and Kitsch by Guiliana Angotti (Class of 2025)

36 ... The Melancholia of a Living Statue by Renny McFadin (Class of 2024)

39 ... Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Guilt of the Golden Teeth by Diego Medal (Class of 2026)

42 ... Golden Love by Sierra Manja (Class of 2026)

45 ... Tawny Chatmon’s Children of Gold by K’Vahzsa Roberts (Class of 2023)

15

All That Glitters: Schiaparelli Spring/Summer 2022

by Elizabeth Brady

by Elizabeth Brady

Elsa Schiaparelli was made famous by her eccentric, revolutionary, yet paradoxically refined style. Especially evident

in much of her work is a love for adornment, additives and all things gilded. A stunning example of this design sensibility recently resurfaced in the Schiaparelli Spring/ Summer 2022 collection.

Look 10 seems to be a pointed homage to one of Elsa

Schiaparelli’s earlier creations, a high-necked velvet cape with intricate gold metallic beadwork titled Apollo of Versailles’. Look 10 was worn on the runway back-to-front, to ensure that the ornate, glimmering beadwork of the coat would be on full display.

Apollo of Versailles was designed by Schiaparelli and embroidered by artist and

16

artisan Lesage in 1938 as part of her famous “zodiac” collection (Fall/Winter 1938). The cape was commissioned originally for actress and interior designer Elsie de Wolfe or “Lady Mendl” as a reference to the Apollo Fountain (Le Bassin d’Apollon)

reign, and the later addition of the figure of Apollo was created and gilded by Roman-born and French-educated sculptor JeanBaptiste Tuby.

The motif of Apollo bringing the dawn was popular during King Louis’s reign,

in the Parc de Versailles, which was close to de Wolfe’s home.

The grandeur and sumptuousness of Look 10 runs deep, the statue it’s based on was commissioned by King Louis the XIV, a monarch famous for his expensive taste and aesthetically finicky nature. Le Bassin d’Apollon existed in a different form as Lake of the Swans during King Louis XIII’s

and he is often pictured in art from the era in his horsedrawn chariot bringing forth golden rays of sunlight. Its predominance as a symbol during this era is no coincidence, seeing as King Louis was often referred to as the “Sun King,” due to the period of growth and prosperity his reign created.

In Look 10, streams

17

of gold beading pour out in a starburst pattern against the simple black background, as though the wearer is bringing the dawn itself with them everywhere they go. In wearing it, the wearer not only depicts Apollo, but in a way also becomes Apollo, exposing the space they occupy to golden light via the garment. In this way, the garment functions as almost a costume, it exists ornamentally and aspirationally. Gold is a prominent theme throughout the Schiaparelli Spring/Summer 2022, with some garments seeming to replicate the naturalistic forms of gold as it’s first mined. It twists and beams throughout the entire collection, at times perfectly reflective, at times pock-marked with precious stones, clinging to models in encasing ergonomic forms, or teased out into springy tendrils or into feather-light ethereal forms that move around the wearer, reminiscent of a model solar system. However, in Look 10, gold is used as

a medium in and of itself, signifying in both a historical and meta-textual way.

Image Captions:

Elsa Schiaparelli, Look 10, Spring/Summer 2022 Collection, satin, wool, gold thread, tubes, beads, Swarovski rhinestones. https://www. schiaparelli.com/en/haute-couture/ haute-couture-spring-summer-2022/ looks/look-10.

Jean Baptiste Tuby, Le Bassin

d’Apollon, 1668-1670, Chateau de Versailles, https://en.chateauversailles. fr/discover/estate/gardens/ fountains#apollos-fountain.

18

Lucretia’s Golden Values

by Lauren Nash

Lucretia holds a dagger towards her chest, wearing an opulent dress with gold detailing and jewelry, likely included to indicate her social status. Her pained expression and pale, clammy skin tone express anguish and sorrow. Subtle highlights on her eyes and skin give her a tearful disposition. A darker background encompasses the figure, with only a dim, light shining on her. Viewers are drawn towards Lucretia’s chest as a focal point, with the surrounding background appearing blurred in contrast. Rembrandt generally uses darker, earthy tones throughout the painting, with varying shades of brown and gold especially present.

The piece is an oil painting on canvas. Rembrandt started with a gray lower layer and a brown upper layer. He incorporated the brown layer

into the background, scraping away some to reveal the gray layer underneath. For the dress, paint was applied rather thickly and freely with broad strokes. Rembrandt blended wet into wet and scumbled with a dry brush. He applied layers of paint for Lucretia’s face, which is visible from the violet and pink undertones. Ochre defines the figure’s lip and makes the dress look luminescent around the waist. There is also little definition of the features on her face, showing rushed brushwork in that area. The back end of the brush was used to create impressions such as those on the figure’s neck and left cuff. Rembrandt also employs the technique of chiaroscuro in this piece, which provides the figure’s static position with the appearance of movement through employing light and shadow.

19

Lucretia was well known in Ancient Rome for her virtue and devotion to her husband. As Livy tells the story, while Lucretia’s husband fought in battle, he boasted to his companions of his wife’s

demanding that she relent to his demands lest he should kill and disgrace her. Out of fear of disgracing herself and her family, Lucretia relented to his demands, but told her husband and father the next day. They

superior virtue, causing them to go back to Rome to see for themselves, where Lucretia proved to the men that what her husband had said was true. This only spelled trouble for her as one of the men, Sextus Tarquinius, would visit her later,

believed she was innocent, but she could not bear to live with the shame she felt and decided to commit suicide by plunging a knife into her chest. This caused her husband and father to begin the revolt against Tarquinius Suberbus and his son Sextus

20

Tarquinius, marking the beginning of the Roman Republic, so she was seen as a symbol of national pride. This idea was present in Rembrandt’s time, with a poem in 1660 referencing Lucretia as a figure associated with freedom. It is possible that Rembrandt painted her, inspired by the parallels between the Roman and Dutch Republics. Rembrandt’s fascination with Lucretia may have also formed from his experiences with emotional trauma. He likely felt a sort of understanding for Lucretia’s pain and her tragic decision to end her own life. In addition, Rembrandt may have associated Lucretia with his romantic partner, Hendrickje, finding parallels between both women’s faithfulness to their partners. Despite being praised for her virtue, Lucretia has faced some derrogation from the church because of her decision to commit suicide. Rembrandt captures Lucretia’s hesitation in this moment to show that she feels a sort of inner

turmoil, reflecting a concern for Christian denouncement of her actions.

I appreciate this work as both an artist and a latin scholar. Rembrandt’s strong employment of texture appeals to me, as this technique adds a sense of character to the painting and prevents Lucretia from appearing stiff and unfeeling. Such rapidly applied strokes create a sense of motion and life, adding personality and avoiding creating an image of perfection. In addition, having learned about Lucretia’s story from the perspective of the Roman historian Livy, it was interesting to see a more modernized take. Rembrandt effectively humanizes a woman that is almost larger than life, embodying the role of a martyr for Roman freedom and a symbol of the kind of duty and sacrifice once expected of women. Lucretia’s blurry, hazed expression captures her mortality, reminding the viewer that she is not beyond fault and flaw, no matter how much she is

21

Image Caption:

Rembrandt van Rijn, Lucretia, 1664, National Gallery of Art, oil on canvas, https://www.nga.gov/collection/artobject-page.83.html.

memorialized. The painting serves to honor Lucretia’s legacy, but also reminds us to be merciful in our judgment of her choices.

22

Projection of a Public Image: Analyzing the Functionality of a Gold Aureus of Agustus

by Emma Capaldi

Due to both their functionality as forms of currency and portability as objects that fit within one’s palm, coins were ubiquitous throughout the expanse of Roman territory and therefore provided a convenient place for individuals seeking to establish or maintain power to publicly project themselves. This gold aureus of Augustus, the first Roman emperor, was an artistic form within Augustus’ iconographic program through which he established himself as the sole ruler of Roman territory and usher in a new political era.

The obverse side of the aureus depicts the head of Augustus in profile circumscribed by text. The text reads “CAESAR AVGVSTVS DIVI F PATER PATRIAE” which translates to “Caesar Augustus son of a god father of the fatherland.” In Roman inscriptions it was common

practice to identify individuals in respect to their fathers, the phrase son of a god on this coin references Augustus’ adoptive father, Julius Caesar, who in accordance with a decree from the Senate was deified. The final phrase of this inscription, pater patriae, alludes to Romulus, legendary founder of the Roman state, thereby associating Augustus with the glory of the founding of Rome. In just a few words, one seeing this coin is able to learn Augustus’ name, his status as he descends from the powerful, well-known, and deified Julius Caesar, and his position in Roman politics as the sole ruler. Sitting within this ring of inscription is a portrait head of Augustus. He is represented with youthful features, a coiffure of flowing locks, and a laurel wreath resting on the crest of his head. This depiction of Augustus as a

23

as a young man presents a stark contrast to Roman Republican portraiture which was characterized by verism, true representations of individuals depicting their old age, an allusion to their wisdom.

Augustus’ choice to depart from existing artistic style reflects the

the Hellenistic Empire, whose reputation was well known throughout the Roman Empire. He creates this allusion through his ageless facial features and voluminous windswept coiffure, characteristic of representations of Alexander. The reverse side of

political shift he is spearheading from republic to empire that requires him to seek ways to legitimize his claim to assume absolute power. To achieve this, Augustus draws a connection to Alexander the Great, young and successful military leader attributed with the creation of

the coin similarly depicts an individual in profile, but bears a representation of a woman seated on a throne wrapped in drapery holding a branch in her left hand and a fairly tall staff in the right. She is shown in an unnatural pose as her head and legs face toward the side, while

24

her chest and shoulders face the viewer. She is flanked by text reading “PONTIF MAXIM,” “highest priest,” alluding to Augustus’ role as both chief political and religious leader of the Roman Empire. This female figure may be a representation of Livia, Augustus’ wife, or a personification of peace in turn referencing the prosperity and

to have one and see the image of their ruler. In addition to its practical function, this coin’s high degree of portability made it an ideal medium to convey representations for wide public consumption.

This aureus is from Lugdunum, an ancient Roman city in Gaul and modern day Lyon, France. Due to the

peace that Augustus established in the Empire.

As currency, coins, such as this Gold Aureus of Augustus, were used by the majority of the Roman population on a daily basis and required mass production making it quite a common occurrence for an individual

lengthy distance between Lugdunum and Rome, it is unlikely that any people living in Lugdunum had ever traveled to Rome where many images of Emperor Augustus were on public display, therefore, coins provided Augustus with a means of presenting an image of himself to those who lived

25

far away from the capital city. Coins, like other forms of art and architecture, contributed to Roman Emperors’ construction of a particular narrative for themselves, a narrative that conveyed power and success, justified their right to rule, and made them an appealing figure for the Roman public to support.

Image Captions:

Gold Aureus of Augustus, Lugdunum, 7.77 g, 13-14 CE, Roman Empire, gold, Lawrence University & Buerger Coin Collection, https://jstor.org/ stable/community.9483293.

Tetradrachm: Head of Alexander (obverse); Athena (reverse), Greek, Macedonian, minted at Lysimachia (thrake), reign of Lysimachos, 297281 BCE, silver, The Cleveland Museum of Art. https://clevelandart. org/art/1917.984.

26

Byzantine Jewellry: Was Jewellry considered upper class good?

by Aurora Noacco

Whether to celebrate a birthday, an anniversary, a wedding, or any other happy event in our everyday life, we rely on jewellery as a trusted present. This is not a coincidence! If we step back in time, indeed, gold symbolises

harmony, peace, and wealth, protecting the loved person against bad luck or harm.

During the Byzantine Empire, jewellery was considered art. Tailor-made designs, enriched with pearls and gems, became popular among the middle classes. One

law in particular among a set enacted by Emperor Justinian in 529 CE catches our attention with respect to jewellery. He explicitly states that “every free man is authorised to wear a gold ring”. Thus, other precious metals and gems could have been worn only by the upper class or just by the emperor himself.

The Mosaics of the San Vitale Basilica, Ravenna, might be used as a reference, especially the two main pieces: Justinian Mosaic and the

27

Theodora Mosaic, completed in 547 CE. The majesty of the gold background enhances the main characters, the Emperor, and the Empress. The background melts with the halo and eases the transition to the crowns. Both these mosaics demonstrate that pearls and gems were reserved for royalty. Moreover in the Theodora Mosaic, her figure is decorated with an excess of pearls, emeralds, rubies, and gold coins. Moreover, as we can see in the mosaics it was a custom, for both men and women, to wear bangles and anklets.

The lucid and vibrant appearance was given through the usage of cloisonné, an enamel technique to mount gems and pearls. This is enhanced by the opus interrassile, a metalworking

technique that gives to the gold all the small bumps and details as in the brooch below.

For the Byzantines, jewellery was necessary to show power and wealth. Now, it doesn’t have the same meaning anymore. The fact that modern pieces are handmade, enables the customer to choose their own design, it is a way of self-expression, where its deep meaning is not to show the social class, but it shows individuality, beliefs and essence of the owner.

Image Captions:

Court of Emperor Justinian with (right) archbishop Maximian and (left) court officials and Praetorian Guards, 547 CE, tesserae mosaic, Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy, https:// www.artesvelata.it/basilica-san-vitaleravenna/#I_mosaici.

Disc Brooch, Middle Byzantine, 7th-9th c., gold, enamel, pearl, silver, https://www.britishmuseum.org/ collection/.object/H_1865-0712-1.

28

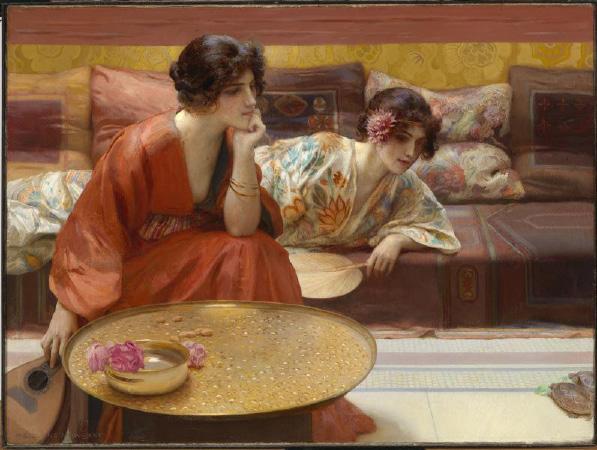

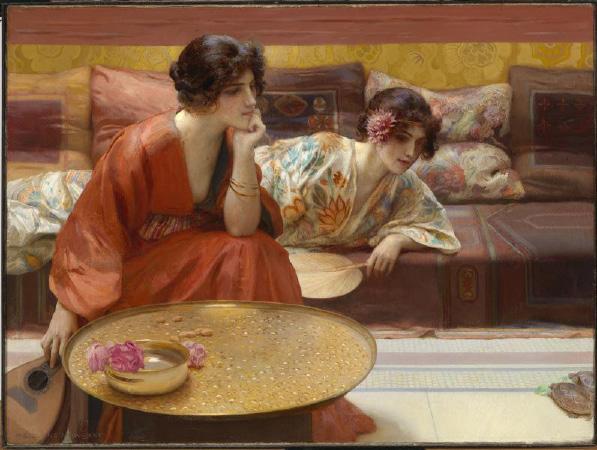

The Gilded Age: What’s Looming Beneath

by Lulu Griffin

Following the years of the Civil War and the turn of the 20th century, America saw a boom in industry and technology. Though wealth and prosperity due to technological advancements were abundant, these advancements were a veneer: scintillating gold on the outside, but greed and corruption loomed just beneath the surface. Coined by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner in 1873, the term “Gilded Age” was an ironic comment on society, contrasting a true golden age and their present time.

The painting Idle Hours depicts two women clothed in silk robes, observing two turtles on the floor. The woman who is sprawled upon the sofa holds a fan, a flower tucked behind her ear; the woman who is seated before a golden table strums a mandolin, shiny bangles adorn her wrist.

Harry Siddons

Mowbray, an American artist known for his commissions for J.P. Morgan and F.W. Vanderbilt (among other clients during the Gilded Age) creates this scene: an amalgamation of an Edith Wharton novel, an author known for portraying the lives and morals of the Gilded Age with knowledge from the New York “elite”, and a painting by Eugène Delacroix, arguably one of the most notable painters from the French Romantic artists. Painters of this era worked to create elegant lines, color, and composition; often, they strived to emulate the most glamorous lifestyle in their paintings, creating works that seemed “better than reality.”

Idle Hours is a vibrant scene, though not necessarily exciting. Visually, the piece is very rich, incorporating texture everywhere: the silk robes, the

29

patterned pillows, the gilded wallpaper, the perforated table –all of which enhance the status of the women. The choice to use oil on canvas reflects the advantages of a large depth and bright hues of color. Mowbray clearly uses vivid colors with lots of oranges, yellows, and pinks. These details work to tell a bigger story of an idealized

more thrilling to them than watching a couple of turtles. This dynamic is indicative of the shallow materialistic culture of the ruling class at the time.

Still, there is a detachment between the scene in the painting and audiences. Perhaps it’s because the subjects of the painting are not looking outward, rather casting their

version of the world. Each brush stroke is intentional; Mowbray ensures the scene comes to life. The painting itself feels very lazy, but in a refined way – like the two women are simply luxuriating on a late summer’s day, existing in this realm of exquisite domesticity, nothing

gaze upon something so minute in the corner. Or, perhaps it’s because the lifestyle depicted is seemingly unimaginable and unrelatable to the majority of the working class.

Nonetheless, this detachment does not deter the public from the fascination with the wealthy. People have

30

The Gilded Age, originally satirized by Twain and Dudley, has made its way full circle today in 2022 as we saw the 2022 MET Gala’s theme: The Gilded Age. But hey, maybe feathered hats and gilded gowns are coming back in style – who knows what could be coming next, or rather, looming beneath!

Image Captions: Harry Siddons Mowbray, Idle Hours, 1895, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art. https://americanart. si.edu/artwork/idle-hours-18016.

always idealized materialism, consumerism, and living life to an excess of extravagance.

31

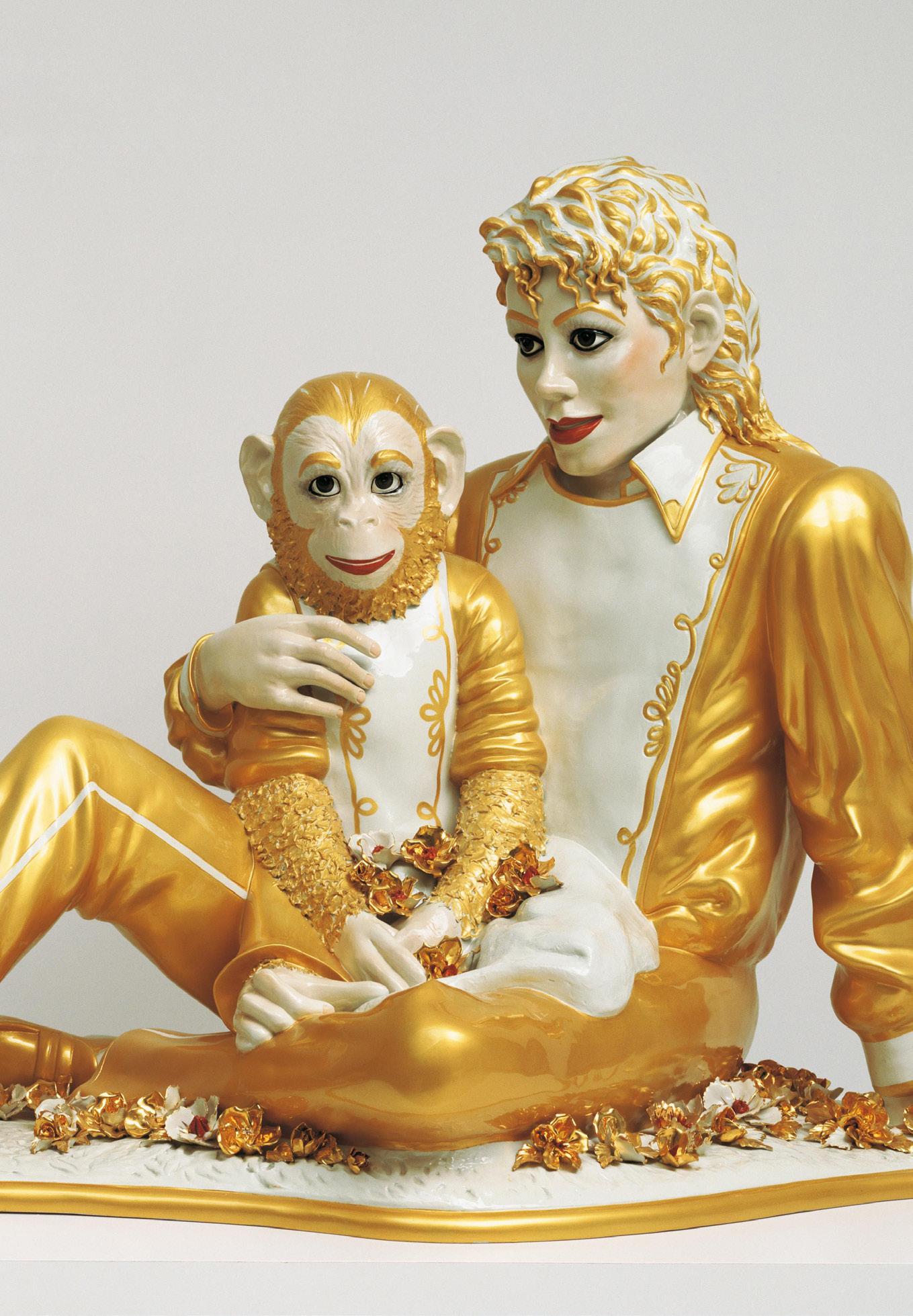

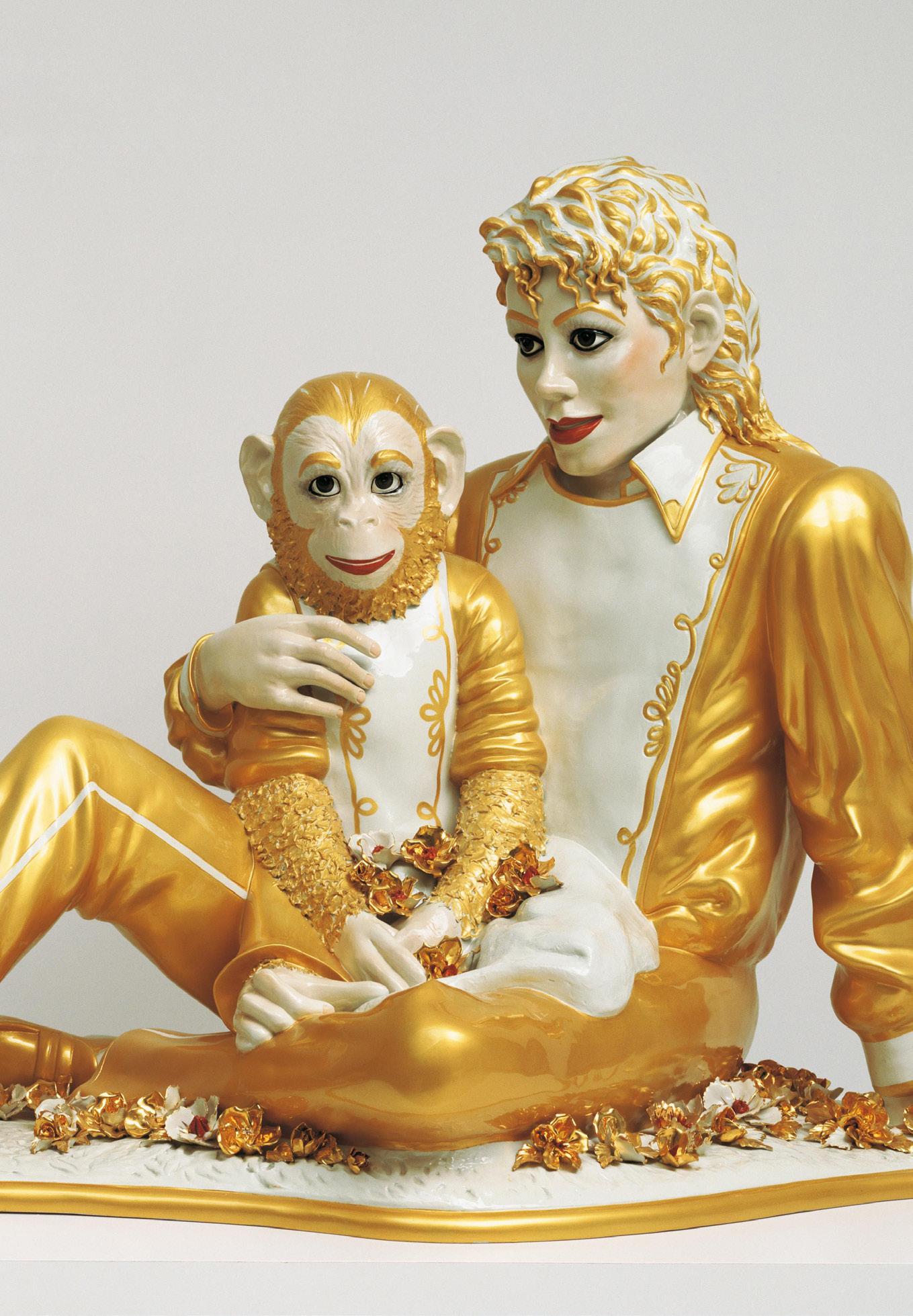

Gold to the Extreme: Jeff Koons and Kitsch

by Guiliana Angotti

There is something undeniably off-putting about Jeff Koons’s Michael Jackson and Bubbles. Strained by a scheme of gold and porcelain, its bizarre countenance is compromised only by the rouge Koons liberally applied to Jackson’s face, as though to imply that the sculpture has come to life. The entire work gives off an air of meanspiritedness, of purposeful insult, and yet what precisely about it is disrespectful? Is it that such an excessive use of gold is somehow demeaning to the class and prestige of Jackson’s name? Perhaps, but Michael Jackson was an incredibly glamorous figure, an element of gaudiness was a part of his brand. Or is it that Jackson himself is an unworthy subject matter for this medium, for his level of decorum, for the very salon in which he sits. On the face of it,

Koons’s work seems to be a joke made at fine art and the people who enjoy it. While there is a desperate grasp at context referred to by the materials – a harkening back to the mythological idealizations befitting Greece and Medieval Europe – there is no real seriousness contained in Michael Jackson and Bubbles. The composition and contextualization of the work oblige artists to configure a Madonna out of Michael, but perhaps what Koons has actually achieved is kitsch. Michael Jackson and Bubbles was exhibited in 1999 but sixty years earlier, Clement Greenberg published Avant-Garde and Kitsch, the immediately influential essay that defined the term into the art zeitgeist. “Kitsch,” defines Greenberg, “is a highly academic aesthetic.” It subdues

32

culture to irony, forces us to reread the serious as stupid and absurd. No longer able to be taken seriously, kitsch invites criticism into an otherwise unquestioned setting. It disillusions the simulation that is representative art, performed, however, with such wild ineptitude that we become

aware of it. At the very least, it leaves us feeling subtly off.

Koons’s use of gold is undeniably kitsch in that we are off put by it. Gold, the quintessential holiness from Renaissance to Romanesque, the reliquary vessel reserved for saints and emperors, is treated

with such frivolousness that we are momentarily awakened to the arbitrariness of its exaltation. In the hands of Jeff Koons, gold is defiled from divine to gratuitous, suddenly it’s as though we’ve eaten too much cake. What does Michael Jackson with Bubbles ask us to understand as viewers? A debasement of the old gods, an introduction of new ones? Is there perhaps a commentary on wealth, its amassment, its materiality, its investment in the cultural landscape?

It’s entirely possible that Koons’s work says nothing at all and that may be precisely

33

what we desire from it. Gold is valuable because it allows ourselves an objective goodness, a proper glamor that is beyond aestheticism. Gold as a metal is soft and unuseful for labor, its value arrives solely from our intent to admire it and in this, we are freely taken out of ourselves. Conversely, the unearthed existentialism of kitsch wakes up what is put to sleep by gold, and we are left with an emotional vacuum. We know that Michael Jackson and Bubbles is not beautiful but we have an inclination to at least compare it to glamor. Gold invokes the power of kings and in this way we are led to a logical conclusion of the sublime. But the fact that it’s Michael Jackson, clownishly made-up with a tacky outfit to match, and his pet monkey invites the comical. It befits the most primal aspect of kitsch: the anti-space, a concept with negative evidence.

Yet, it is by a long shot incorrect to say that Michael Jackson and Bubbles detracts

from any room in which it is placed. It has become increasingly mainstream knowledge that Classical sculptures used to be thickly covered by layers of colorful paint, but that this paint has never been restored as the colorless product displays more dignity. Jeff Koons directly assails this notion with his own layers of paint, bright gold paint, a signal that should remain unambiguously good and yet only causes us to realize an alienating caveat to our definition of attractiveness. Is it true that we have moved past gold? Has our more enlightened mind abandoned the need for glamor with the arrival of poststructuralism and mass culture? These are the questions surrounding the contemporary kitsch of Jeff Koons’s work, and unfortunately, we are only left with more questions. Whether or not Koons’s work can be considered kitsch is debatable – some say that kitsch can only exist purely in the Kantian preethical utopia of an inhibited

34

mind, while others argue for a more purposefully ironic interpretation that Koons himself seems to align more closely with. What Michael Jackson and Bubbles seems to offer us in exchange for all of these questions however, is the gleam of light from the museum overheads that bounces off Jackson’s crown of angelic yellow hair, an upturned shoe that, in the triumphancy of its eternal good fortune, will always give us a place to rest our eyes.

Image Caption:

Jeff Koons, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, porcelain, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, https://publicdelivery.org/wp-content/ uploads/2015/12/Jeff-Koons-MichaelJackson-and-Bubbles-1988-ceramic106.7-x-179.1-x-82.5cm.jpg

35

The Melancholia of a Living Statue

by Renny McFadin

What is it like to be an object? The subject of unguarded, and often unwanted, gaze? Woman in E, a performance piece by Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson (b. 1976), seeks to encapsulate this feeling. The piece is an imposing visual onslaught of gold. Situated in the Hirshhorn Museum in 2016, Woman in E features a woman adorned in a gold sequin floor-length evening gown standing upon a revolving pedestal. The surrounding area is a barricade of gold tinsel, enshrouding the area where she performs. Her pedestal is covered in the gold garland as well, creating a visually cohesive, if not gaudy, effect. The anonymous woman monotonously strums a single chord on her white Telecaster: E minor.

Throughout her performance (she only gets a break every two hours), she

simply revolves, strums the chord, and resolutely does not react to the surrounding spectators. She’s a living, breathing statue. She’s an idol upon her plinth, forced to be the focus of an unrelenting audience’s gaze for her tenure as the Woman in E. The notion of a woman being a statue is particularly poignant when considering the location of this installation: Washington D.C.. In the home of America’s most popular statues, Woman in E is a stark contrast to her maledominated peers.

Along with the contrast to her inherently masculine environment, other themes of femininity are tied to the idea of the living statue. The natural objectification that occurs in her performance is deeply rooted in the female experience. This notion was of concern to many of the performers associated

36

with Kjartansson’s piece. Adrienne Shrute, a Woman in E from Richmond, stated that “You become an object, and people don’t see you as a person.”

The statuesque feeling of Woman in E is further

heightened by its gold motif. Kjartansson plays with classical notions of beauty in the statuary arts: the belief that gold is somehow a superior and “classier” material, and therefore something that is worth more. However, the mediums in which Kjartansson employs the color come across as “tacky” and even kitsch. The

gold tinsel appears cheap, but it encloses the entire exhibit, making the viewer feel as if they are almost forced to gaze upon the Woman. The Woman is also wearing a gold evening gown, which is beautiful, but comes across as garish with its sequins and gold tawdriness. The tackiness of the gold adornments within the piece serve as to further objectify the woman and remove her from her status as a person in order to force her into the role of being a statue.

Woman in E is incredibly melancholic, underscored by her music and

37

the emotions that it evokes from its audience. One cannot help but feel sorrowful for the women who must stand up on the pedestal all day, playing the same note, being gawked at by any passerby. She has truly become an object of gold by virtue of observation. However, one can also gain empowerment as a Woman in E. We, the audience, are allowed to see into this golden portal of her performance, permitted by the woman herself.

Image Caption:

Ragnar Kjartansson, Woman in E, 2016, woman dressed in gold gown on a rotating pedestal, playing an electric guitar, The Hirshhorn Museum, https://washingtoncitypaper.com/ article/327735/photos-rehearsal-forragnar-kjartanssons-woman-in-e/.

38

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Guilt of Golden Teeth

by Diego Medal

by Diego Medal

What’s the quality shared between Jean Michael Basquiat’s artwork and gold? They are deceptively simple.

Throughout history, gold has been a “pure” color associated with royalty and high value. The color has been

increasingly shown interest in the dynamic between the color gold and its idealizations. Perhaps the color gold could symbolize corporate greed, urination, or any other degrading concept that takes it away from its original

closely tied to upper-class status and wealth, a distinguishing pigment in almost any work of art. It’s almost as if, in essence, the color has held some sort of higher power throughout art history. However, some contemporary artists have

utilization in art.

In a similar fashion, the art of American artist Jean Michel Basquiat can at first glance seem quite simple: amateurish doodles, a spluttering of color all over the

39

place, and unintelligible writing. Nothing more, nothing less. Hidden under the surface, however, lies a much darker, emotional truth of Basquiat’s paintings. To me, Basquiat’s art is the embodiment of childlike wonder and innocence…. going through the shredder of reality. All of the aspects that make his art “gibberish” lay an ideological foundation for using simplicity to communicate complex ideas.

So, given the background of these two simple complexities, one can logically ask the question: what would be their production when they crash into one another? The response comes in the form of Basquiat’s 1982 painting Guilt of Golden Teeth. Commissioned by Emilio Mazzoli for his gallery in Modena, Italy, the work acts as a commentary on capitalist greed and the ugliness that comes from revealing society’s hidden demons.

The most notable characteristic of the painting is the white-faced stick figure in

the middle of the frame. The figure, made up of simplistic attributes like straight lines, smudges of paint, and a circular “halo” that highlights the figure’s painted face and crooked gold teeth, in my eyes forms a stand-in for a greedy top-hat capitalist. This narrative of corporate greed is taken further by the word “Peso Neto” (which translates to “net weight”) on the left side of the figure. The titular golden smile, with its misshapen figures, reminds me of a smile one would make when they know that they are caught; giving the feeling that they (the ones who severely messed up society) have done nothing wrong.

In this work, the purity historically associated with the color gold is being flipped on its head to symbolize something that is impure and vile. As a young man forced to experience the dark underbelly of life in New York (especially for a black man), Basquiat’s “simple” and “amateurish” style gives him the freedom to explore

40

complex societal issues in an interesting manner. Upon seeing Guilt of Golden Teeth, the audience intuitively understands the critique of the capitalist system through the distortion of the golden-teethed figure. As with most aspects of art, the usage of gold is a purely relative one; it can be used by either the wealthy for status or by revolutionaries (like Basquiat) to challenge society’s norms and perceptions.

Image Caption:

Jean-Michel Basquiat, The Guilt of Golden Teeth, 1982, acrylic, spray paint and oilstick on canvas, Held in private collection, https:// www.artnews.com/wp-content/ uploads/2021/10/BASQUIAT-TheGuilt-of-Gold-Teeth.jpg.

41

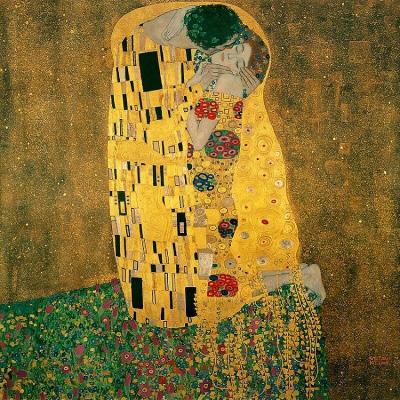

Golden Love

by Sierra Manja

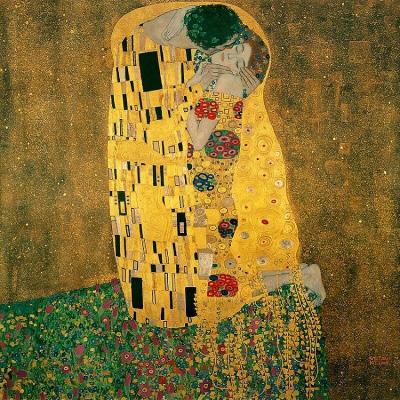

A renowned embrace is recognized in Gustav Klimt’s, The Kiss. Here, a crown of leaves sit atop a man’s head,

garments, they are displayed as one figure, a single entity. In their physical embrace, the man’s arm is draped around the

who bends down to kiss a woman’s cheek. The woman’s hair is scattered with flowers, complimenting the floral pasture the couple stands on. The man’s attire is made up of rectangular shapes, as circular assortments compose of the woman’s. Despite the lovers’ varying

woman’s neck firmly, and her’s softly around his. He lifts her face towards him, the contrast of their skin tones apparent. As for the background, the entirety of the space is gold. The figures against the golden background creates a halo around them. The

42

embrace takes place on the edge of a hill, which trails off the canvas into the abyss. Klimt utilized a variety of gold types in order to produce this masterpiece. The Kiss is an oil on canvas painting spanning six feet in width and six feet in height. The life size nature of this work fully encapsulates the observer in the golden world of love. A variety of eight types of gold were used in the creation of The Kiss. The luminous background is the result of a new technical invention, where sheets of gold leaf covered the entire canvas, which was then painted over with a dark wash, and finally gold flakes were flicked atop.

To the artist, The Kiss displayed him & his love. Emilie Flöge, the love of Klimt’s life, is suspected to be the woman in the piece. Nearly 400 letters from Klimt to Flöge exist today, displaying their constant admiration for one another. The two never married, yet were known as life companions, inseparable

until Klimt’s death in 1918. This elevates the use of gold, as Klimt believed a work portraying his love should be composed of the most valuable material. What is love if not gold, the most precious thing in the world?

The Kiss encapsulates Klimt’s admiration for Byzantine art in a contemporary manner. In 1903, Klimt traveled to Italy, where the use of gold, specifically in mosaics, infatuated him. Klimt wrote, “the mosaics are of incredible splendor,” and thus was driven to incorporate their most notable material: gold. What would The Kiss be without gold? Gold is the motivating factor for not only The Kiss but the artist’s “Golden Period.”

To me, no work, classical or contemporary, encapsulates the passion and danger of love quite like The Kiss. At first glance, the work was straightforward to me: two lovers. Upon investigation, The Kiss increases in splendor, as it tells a story of love. First, I see

43

Image Caption: Gustav Klimt, The Kiss, 1907-1908, oil and gold leaf on canvas, Belvedere Museum, Vienna, Austria, https:// www.gustav-klimt.com/images/ paintings/The-Kiss.jpg.

the two figures intertwined as one, the way love unites people.

I see the cliff setting as the ever constant possibility of the loss of love. Despite danger a step away, the couple’s love is unaffected. Perhaps the fear of the end is what motivates the lover’s passionate embrace.

44

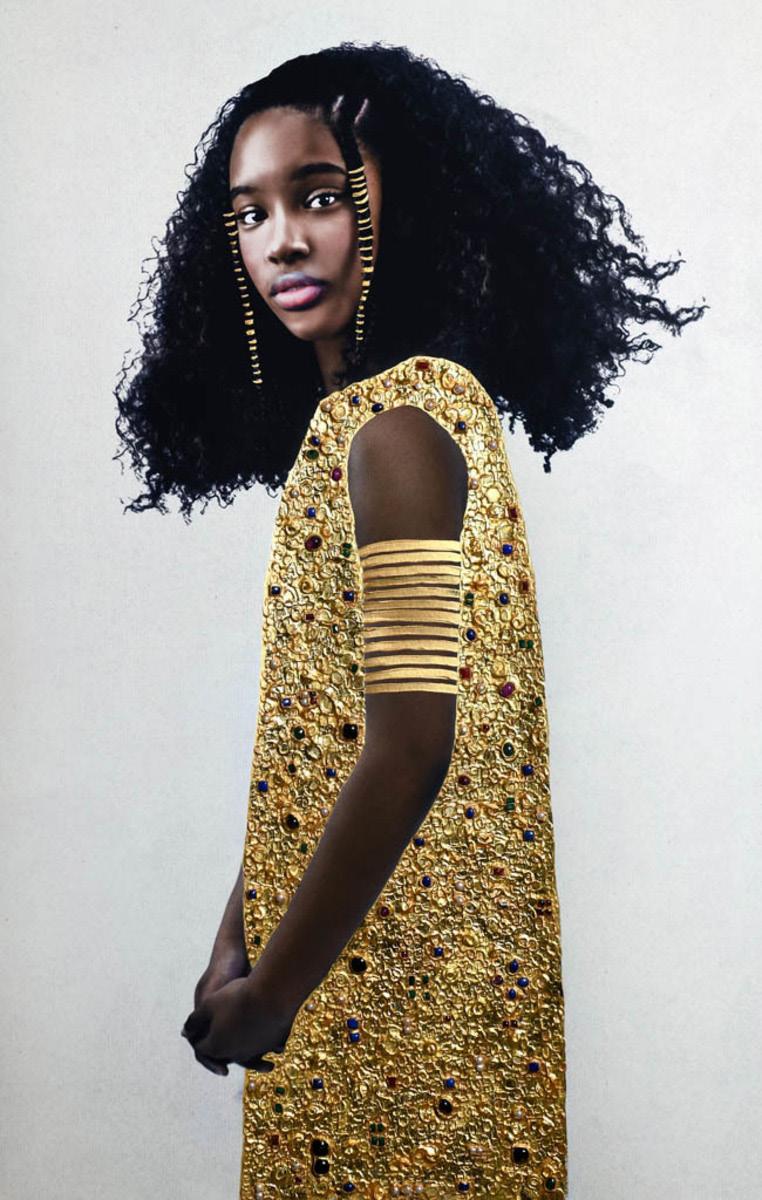

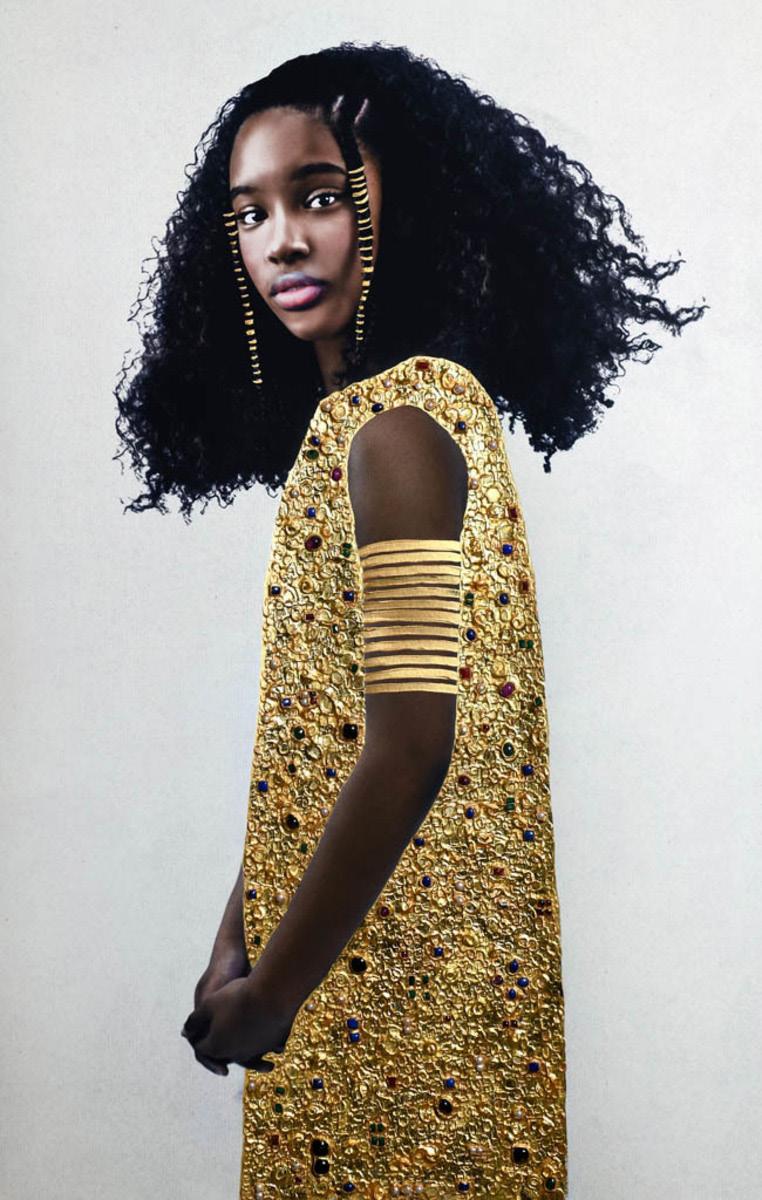

Tawny Chatmon’s Children of Gold

by K’Vahzsa Roberts

Tawny Chatmon is a Maryland-based artist whose work focuses on the beauty and value of Black children. Using her experience as a professional photographer to take stunning portraits of her subjects, Chatmon then embellishes the compositions with gold-leaf to emphasize their worth. The painting techniques that the artist uses are very reminiscent of that of Gustav Klimt, whose work is often revered for its use of gold-leaf. However, Chatmon turns this tradition on its head by bringing Black bodies to the forefront of the canvas, as opposed to the margins where they historically reside. In most of her portraits, the background is left blank, leaving these children as the only focal point.

For example, in her work, Destined To Lead The Way (2021), this use of negative space helps to capture the position of the young girl.

Even in the midst of so much adornment (in addition to the 24k gold-leaf, Chatmon also utilizes precious gemstones such as African ruby, emerald, and amethyst), the viewer is still drawn to the depth of her expression and the gracefulness of her clasped hands. Like Klimt, the artist is able to balance the extravagance and detail of her painting with the importance of the human figure.

As a response to the many injustices faced by Black Americans in recent years, Chatmon decided that her artwork could be a way for those who look like her to see themselves in a different light. In a 2021 interview with The Washington Post, the artist says that she uses the gold because it shows these children that they matter, since, in antiquity, the medium was reserved for the most special of circumstances,

45

and people. By drawing comparisons between these children and European royalty, Chatmon is critiquing the status of these figures and how they are seen today versus the Black body, which has been socially disregarded.

The subject’s gaze is directed to the viewer, even though her body is standing in profile. Chatmon keeps her expression soft, emphasizing her childish innocence, which is the focal point of the painting. When juxtaposing this softness to the ornamentation of her gold dress, the artist creates a relationship between the purity of the child and the regality of the material. However, gold is not just a symbol of grandeur, it is also a symbol of strength, and Chatmon uses this to her advantage. The gold in the girl’s hair, dress, and the bands on her arm feels very solid, so she comes across as more of a warrior, than a princess.

In this instance, gold is not merely decoration, but an indication of her character,

which is both delicate and tough. Chatmon manipulates material and composition to expand the viewer’s perception of what it means to have power in a narrative.

Tawny Chatmon, Destined To Lead The Way, 2021, 24k gold leaf, acrylic, precious and semi-precious, stones, https://www.thisiscolossal.com/wpcontent/uploads/2021/11/chatmon-9. jpg.

Image Caption:

Image Caption:

46

All That Glitters: Schiaparelli Spring/Summer 2022

by Elizabeth Brady

Elsa Schiaparelli. “Apollo of Versailles.” Met Museum. https:// www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/81142.

“The Fountains.” Château de Versailles. https:// en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/estate/gardens/fountains#apollosfountain.

“The Story of the House.” Schiaparelli. https://www.schiaparelli. com/en/21-place-vendome/the-story-of-the-house/.

Lucretia’s Golden Values

by Lauren Nash

“Lucretia, 1664.” National Gallery of Art. Arthur K. Wheelock Jr., Accessed October 25, 2022, https://www.nga.gov/collection/artobject-page.83.html#entry.

Projection of Public Image: Analyzing the Functionality of a Gold Aureus of Augustus

by Emma Capaldi

Augustus. Gold Aureus of Augustus, Lugdunum, 7.77 g. 13–14 CE. https://jstor.org/stable/community.9483293.

Grant, Michael. “Roman Coins as Propaganda.” Archaeology5, no. 2 (1952): 79–85. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41663050.

Bibliography

47

Tetradrachm: Head of Alexander (obverse); Athena (reverse). Cleveland Museum of Art. https://clevelandart.org/art/1917.984.

Byzantine Jewellry: Was Jewellry considered upper class good?

by Aurora Noacco

The British Museum . n.d. Disc Brooch. Accessed October 2022, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1865-0712-1.

Nifosì, Giuseppe. 2020. La basilica di San Vitale a Ravenna e i suoi mosaici. September. Accessed October 2022, https://www.artesvelata.it/basilica-san-vitale-ravenna/#I_mosaici.

The Gilded Age: What’s Looming Beneath

by Lulu Griffin

“Gilded Age.” HISTORY, A&E Television Networks. Last modiefied February 13, 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/19thcentury/gilded-age.

“The Gilded Age: AMNH.” American Museum of Natural History. https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/gold/golden-ages/the-gildedage.

“Idle Hours.” Smithsonian American Art Museum. https:// americanart.si.edu/artwork/idle-hours-18016.

“Idle Hours by Henry Siddons Mowbray.” Artvee. https://artvee. com/dl/idle-hours/.

48

Gold to the Extreme: Jeff Koons and Kitsch

by Guiliana Angotti

Sutton, Kate. “Jeff Koons’ Controversial Michael Jackson Sculpture: The Story Behind It.” Billboard. Last modified July 8, 2014, https://www.billboard.com/music/music-news/jeffkoons-controversial-michael-jackson-sculpture-the-story-behindit-6150392/.

The Melancholia of a Living Statue

by Renny McFadin

Catlin, Roger. “For ‘Woman in E,’ the reverberation ends.” The Washington Post. Last modified January 5, 2017, https://www. washingtonpost.com/for-women-in-e-the-reverberation-fad es/2017/01/05/f92a97d0-d1c8-11e6-9651-54a0154cf5b3_story. html.

“Ragnar Kjartansson– Woman in E.” Hirshhorn. https://hirshhorn. si.edu/explore/ragnar-kjartansson-woman-e/.

Ulaby, Neda. “Art Star Ragnar Kjartansson Moves People to Tears, Over and Over.” NPR, All Things Considered. October 28, 2016, https://www.npr.org/2016/10/28/498718095/art-star-ragnar-kjartansson-moves-people-to-tears-over-and-over.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Guilt of the Golden Teeth by Diego Medal

Celis, Ana Maria. “The Guilt of Gold Teeth.” Christie’s. Accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6343225.

49

Greenberger, Alex. “$40 m. Basquiat Painting Headed to Christie’s Looks to Join Artist’s Most Expensive Works.” ARTnews. com. Penske Media Corporation, October 13, 2021, https://www. artnews.com/art-news/market/jean-michel-basquiat-christies-theguilt-of-golden-teeth-1234606882/.

“The Guilt of Golden Teeth.” Jean-Michel Basquiat.org. Art.com. Accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.jean-michel-basquiat. org/guilt-of-gold-teeth/.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Masterpiece ‘The Guilt of Gold Teeth’ | Christie’s. YouTube. YouTube, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=aDh9PIYXa40.

Golden Love

by Sierra Manja

“Gustav Klimt.” Ravenna Turismo. January 18, 2021, https://www. turismo.ra.it/en/culture-and-history/uncategorized/gustav-klimt/.

“Gustav Klimt and His Paintings.” Gustav Klimt: 200 Famous Paintings Analysis & Complete Works. Accessed November 2, 2022, https://www.gustav-klimt.com/.

Stanska, Zuzanna. “Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge - the Everlasting Friendship.” DailyArt Magazine. October 28, 2021, https:// www.dailyartmagazine.com/gustav-klimt-emilie-floge/.

50

Tawny Chatmon’s Children of Gold

by K’Vahzsa Roberts

Streeter, Leslie Gray. “Painter who surrounds her Black subjects with gold.” The Washington Post. February 8, 2022, https://www. washingtonpost.com/magazine/2022/02/08/painter-who-surroundsher-black-subjects-with-gold/.

51

William and Mary Studio Art Major

Minimum Required Credit Hours: 37

Core Requirements

ART 211 - Drawing and Color, and ART 212 - 3D Design: Form and Space

ART 461 - Capstone I

ART 462 - Capstone II

ART 463 - Capstone III

(2) 200-level Art History courses at, or above ARTH 230

(1) 300-level Art History course at, or above ARTH 330

*17 Additional Credits in Two or Three Dimensional Focus Studies

William and Mary Art History Major

Minimum Required Credit Hours: 33

Foundational Courses

(3) 200 level courses at or above ARTH 230 to ARTH 299

ART 211 - Drawing and Color, or ART 212 - 3D Design: Form and Space

Core Requirements

ARTH 331 - The Curatorial Project

ARTH 333 - Theories and Methods of Art History

ARTH 493 - Capstone Seminar

*9 Additional Credits at or above ARTH 330 and 1 Elective Course

52

by Elizabeth Brady

by Elizabeth Brady

by Diego Medal

by Diego Medal

Image Caption:

Image Caption: