ACROPOLIS

ART & ART HISTORY JOURNAL

FALL 2024

Reflection

Editors:

Giuliana Angotti

Sierra Manja

Staff:

Giuliana Angotti

Zoe Davis

Briana Edwards

Lauren Nash

Sierra Manja

Katrina Raab

Cecilia Soukup

Anastasia Soutos

Clare Yee

The theme Reflection was chosen by our staff as a concept ever-present in the trajectory of art history. It is art’s great purpose to communicate the unknown or hidden aspects of the world, society, subject, and artist. Inspired by introspection, the present articles, submitted by our student body, explore the use of reflection by Old Masters to photographers, modern sculptures, and iconic abstract works. Through such genres we will explore the power of art in reflecting themes of identity, transformation, and the search for meaning.

In picking the theme Reflection we hoped to encourage our readers to investigate images beyond the present visual. Each piece is an invitation into a unique perspective and a moment of vulnerability, and we are eager to share this world of reflection with you.

Sierra & Giuliana

Reflection (n.)

The throwing back by a body or surface of light, heat, or sound without absorbing it.

Serious thought or consideration

Art Poetry

Contents

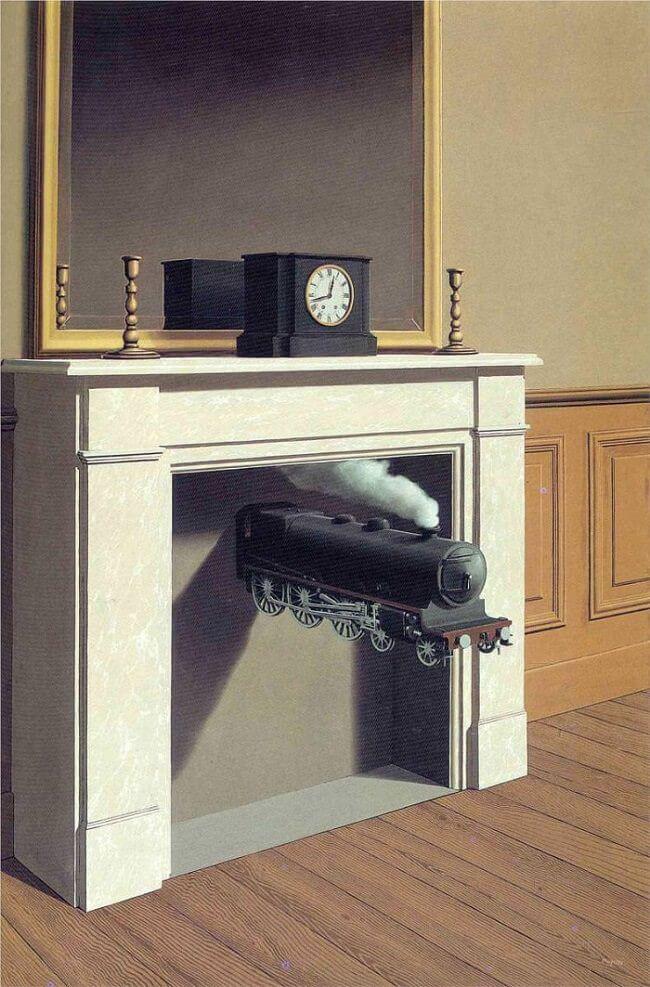

6 ... 6:16 Train Overdue by Rob Hochstetter (Paired with Rene Magritte, La Durée poignardée, 1938)

8 ... Extinguish Etude by Briana Edwards (Paired with James McNeill Whistler, Nocturne in Black and Gold, The Falling Rocket)

6:16 Train Overdue

Rob Hochstetter

I look at the clock in the corner of my eye

It reads “6:16”, and I frown

The train is one minute overdue

I’m changing tracks, and changing towns

The station’s bitter air bites my trembling hands

Its ceiling, a sky built of glass

But the angels have all gone away

For they know that all things must pass

In my pocket, I find the ticket has gone

As the foreign rain starts to pour down

They say some of us will stay behind

As the sky now lies upon the ground

I look at the clock once more in the corner of my eye

It still reads 6:16, and so again I frown

Did the train depart while I stared at the sky?

Am I stuck on this track, and stuck in this town?

Rene Magritte, Time Transfixed (La Durée poignardée), 1938.

Extinguished Étude

by Brianna Edwards

You left me late July,

When the sun stayed up past eight and the night hung low in the skies Quiet roads, deer hiding in the woods

You visit me in my dreams

Sweaty bodies, droplets dancing on our skin

We moved in tandem with the music as it eclipsed and rose We were phases of the moon, rapidly waxing and waning in motion Moving around each other as if we had a gravitational pull

You held a kerosene lantern to my face

Kissed my lips and knew all my secrets

I was your disease, a symptom that needed to be cured I floated to the surface, and though I was dead, I spared you the burden by burying myself I used to run on a sloping, vertiginous lawn

Now I lay beneath it, listening to the heartbeat of the earth

We were doomed from the start Nights I snuck out to sit on my back porch

Watching the fire eat and erode the paper between my fingers into nothingness

Sitting on the splintered wood and sharp nails

The smoke caresses my face, then suffocates into thin air, with only my thoughts of you to keep me company

Torn between waiting for you and loving you, and yet you always chose for me

We never said we loved each other

Constructing ourselves as locust keepers

Performing in a theater of ourselvehoods, and I had fun, even as I felt the stars drowning, ripping away the fabrics of time and space Standing as opponents on the opposite sides of a net

I was always trying to win your affections

And though I proved unsuccessful

I surely tried

I tended to the flame as if I were a Vestal Virgin

By blood, sweat, and tears by god I kept it alive

Light another cigarette and another just to keep you close

Only for the fire to erode the threshold, dust slipping through my fingertips Only for the flame to disintegrate and burn away until it snuffed out the heat

Only for the fog to clog my lungs and choke my tears as they trickled

Only for the ashes to clear, and me, hand to the glass door, watching you walk away

And as I say goodbye to you I reflect that I have walked the tightrope of your guitar strings And I have licked the flames off your tongue So when I look back at last summer When I look in my reflection I can see July I can see the setting sun

Because to truly love you is to let you be yourself And that is someone who leaves, taking my memory of you with you

Though I forget your voice, your eyes, and your smile– I set you free

I will always remember you in the summer, when the warm breeze left and you did too.

Critique

Rene Magritte, Not to be Reproduced, 1937

Is it true that you cannot analyze yourself objectively? When discussing the merits of psychoanalysis, Freud said that he was the only one capable of examining his own mind without judgment. For Jacque Lacan, who would follow in the footsteps of Freud decades later, the man we are in the mirror is someone far different from who we actually are in reality.

Rene Magritte was one of the Surrealists. Though not as hotly acquainted with Breton, Dalí, and Ernst, his work still shows clear signs of the influence psychoanalysis had on the movement. Not to be Reproduced, a 1937 “portrait”, was originally commissioned by the poet Edward James, who was a frequent patron of the artist. James had asked Magritte to paint him and yet the artwork does not display his face. Instead, Magritte tells us that this likeness should not be replicated. James’s image, both as a person and as a painted subject, should not be confined to the picture plane – be that as a traditional sitter or as a figure in the subversive picture plane of the mirror itself.

Through the work, Magritte seems to portray his philosophy of the self in high regard. That elusive figure of philosophy, which cannot be entirely known, should not be haplessly chased after. Contained in Magritte’s title diction, “Reproduction” is most often thought to be truthful. In reality, Magritte, who was working in what the theorist Walter Benjamin would call an accelerated period of manufacturing, comes to the audience as weary of anything that elucidates James’s likeness as distributive. Not even mirrors can be trusted. As though there is a kind of entropy of the self that occurs upon reproduction, that which happens when we are looked upon by others or even by ourselves, Magritte’s James definitely preserves himself from our judgements. We can judge the figure of the painting, but only in name is that person actually Eduard James. As a man with his back turned, he is only a stranger.

Zoe Davis

Women of multiple ages, styles, and shapes populate the image. In the blurred foreground, one looks out to the viewer with a hand supporting her pregnant stomach. In the background another rushes to the left, hair whipping behind her, her body made similarly blurry with movement. Centered between the two stand two women, one helping the other with her makeup while the other looks out of frame, lips curling upwards as she comments something — are her words teasing? Sweet? Snarky? Perhaps all three. You can feel their energy, the mad scramble to find their mascara, get their hair into a presentable state, swipe another’s prized gloss over their lips in the midst of the chaos, hoping the owner won’t notice. You know this scene. You’ve been part of this scene in some form or another as a bemused observer or lively participant, contributing to the wider tapestry of movement and preparation. In contrast, the second image is calmer, quieter. The women gaze out at the viewer, their hair loose, positioned in an undulating line of faces that push into the foreground and recede to the background. One looks out in distant curiosity, another smiles softly, and yet another gazes out beyond the image, expression neutral, framed on either side by her companions. This image has a more placid atmosphere than the first, but the subjects are the same: both portray sisters.

Brianna Capozzi is best known for her work as a fashion photographer, having photographed celebrities like Miley Cyrus and Halle Bailey. However in her new book, Sisters, Capozzi departs from the more structured styles for which she is known to capture images more “raw and real” in their subject matter and portrayal. Building on her “tender fascination with women,” Capozzi began the project over six years ago to capture bloodrelated and familial

sisters, informed by her relationship with her own sister. Capozzi describes her project as aiming to “create beautiful images that capture the uncontrived essence of the relationship between sisters” with a focus on “the unembarrassed and genuine sentiment that comes with spending so much time with each other.” Sisters, then, is a culmination of Capozzi’s interest in familial intimacy, femininity, and the beauty that results from their combination.

From wild to calm, crowded to spacious, the images of Capozzi’s Sisters each seem to encapsulate the years shared between women growing with each other and the experiences that result from it. The book, like the world, is full to bursting with sisters each with their unique dynamics but all with a relationship at once strange and familiar. Be it in the rush of preparal or in the calmer moments where these efforts are artfully obscured, Capozzi’s work allows us to see the intragenerational echoes of these women’s features and the bonds shared between them. Sisters explores these relationships and offers instances where the feminine, the familial, and the beautiful coalesce into singular images.

Cloud Gate, or “The Bean” as most Chicagoans call it, stands tall and proud in Millenium Park. It looms over visitors as they walk by, reaching 33 feet. As one walks closer to it, they might notice their reflection start to distort and change, depending on where they stand. The reflective surface almost acts like a funhouse mirror by shrinking and stretching people and the cityscape at different parts of the structure. As one moves underneath the Cloud Gate, one will notice that the surface is reflective, just like the exterior. This shows that the structure never starts or stops, instead it is continuous throughout so that there is no beginning or end. So as visitors walk under the high arch in the middle, they may watch their reflection move with them.

Cloud Gate is a three-dimensional structure that is permanently installed in the city of Chicago. The artist, Anish Kapoor, utilized stainless steel to make the structure shine. He created the structure by using computer technology to cut 168 massive steel plates, which he then placed next to each other and welded together. As a result, the structure appears seamless, with its polished and mirror-like surface purposefully modeling liquid mercury. The piece is also interactive, because visitors may touch the surface, view their reflection, and take photos. Within the structure, two large metal rings are connected by a truss framework, similar to a bridge. This helps concentrate the piece’s weight at either base point and forms the curved area that visitors may walk under. The exterior also connects to the inside frame and can expand and contract with the changing weather. In addition, the piece is tall and heavy with dimensions of 33’ by 42’ by 66’ ft and a weight of 110 tons, which helps it stand out against the rest of the city.

Kapoor named the piece Cloud Gate because it reflects the skyline and has an arched entryway into the park. It stands out

as a horizontal object within a vertical city, creating a visually interesting juxtaposition. In addition, the piece feels very freeform against the rigid and geometric Chicago skyline. This is because of its curved shape and seamless surface which create the appearance of infinity. Its curved shape is also why many Chicagoans and tourists have fondly referred to the structure as “The Bean” instead of using its official name. Kapoor was already well-known for his other outdoor installations prior to creating Cloud Gate, but to this day it has been considered one of his most prominent pieces. It was also his first permanent outdoor art piece in the United States.

As someone who has lived near Chicago most of my life, I have a great appreciation for Cloud Gate. Every time I visit, I always see the structure from a new perspective. This is because Millenium Park and I have continued to change over time, which has altered my view and appreciation of the structure and its surroundings. In addition, there are so many different ways to look at the piece because it lacks a start and end point. Visitors can walk up from any angle and enjoy the piece in their way. It is also enjoyable to see art in a more organic format, where the piece changes with its environment. The structure itself may stay intact, but the environment around it is ever-changing. So, it is unlikely that Cloud Gate will ever look the same at two different points in time.

Caravaggio, Narcissus, 1597

Kneeling at the edge of darkness is Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio’s Narcissus. The true self and the reflective image are divided within the painting by space and form. Above, the dominant character, Narcissus, is characterized by his youth and handsome features. The dramatics of his theatrical dress, a 16th-century style, exaggerates the interplay of shadows and drapery studies. This upper portrait does not appear in isolation, as a continuity appears from Narcissus’ hands, which graze the thin abstract line between the looming water. The intensity of Narcissus’s contemplative and lustful gaze downward connects the two painted figures. Below, the reflected Narcissus appears as a dimmer image, nearly synonymous with the surrounding darkness.

The present image is a representation of the Greek mythological tale of the Narcissus. In such, the attractive youth turns away all romantic advances. Glimpsing his reflection in a natural pool, the boy becomes enamored with his own image. Ovid recites the tale, placing Narcissus “flat on the ground, where he contemplates two stars, his eyes, and his hair, fit for Bacchus, fit for Apollo, his youthful cheeks and ivory neck, the beauty of his face, the rose-flush mingled in the whiteness of snow, admiring everything for which he is himself admired.” (Ovid, Metamorphosis, Book III, 412-414). As Narcissus leans down into himself, seeking to kiss his reflection, he falls into the watery depths. Thus, Caravaggio’s present images actively symbolizes the concept of self-image along with the consequences of vanity.

The artist’s methods allow the tale to take on a new nature. Caravaggio was active within the Baroque movement, characterized by exaggerated motion and darkness, and communicated through realistic detail. Narcissus is representative of Caravaggio’s stylistic contributions to light manipulation. The void background and

subsequent darkness demonstrate tenebrism. Simultaneously, the artist utilizes his notable chiaroscuro, juxtaposing extreme dark with light.

It is the extent of emotional depth and vulnerability within Caravaggio’s Narcissus that initially captivated me. The mirrored replication of the self naturally evokes questions in the viewer as to the value of their identity and the implications of self-realization. The gaze of Narcissus communicates the desperation and desire in the journey of personhood. For Narcissus, his love remains intangible. There is an element of disillusionment, as the painted reflection in the water blurs the details within Narcissus. With this, Caravaggio’s Narcissus becomes a testament to the insatiable desire of the human condition.

Roy Lichtenstein, Reflections on Conversations, 1990

Reflections on Conversation, painted by Roy Lichtenstein in 1990, is one of seven prints in his Reflection Series. The composition is framed by a graphic grey border, the piece shows a couple locked in conversation. Instead of color, Lichtenstein uses Ben Day dots, a technique from industrial printing, to define their skin. Each figure is outlined with thick linework, and the expressive lines help create value. Obscuring the image are pastel washes of color, diagonal lines of even weight, and more Ben Day dots. The entire composition is affected by the reflections, including the light blue, painted mat, except the silver frame.

Lichtenstein’s Reflection Series comes from a failed attempt to photograph a Robert Rauschenberg print. After the glass protecting the print reflected the light from a window, he found it impossible to take a good picture. Realizing that even an obscured image is recognizable if it is well-known enough, Lichtenstein began this self-referential series. After early attempts to recreate the effect through photography, Lichtenstein realized that the reflections could be created through painting as well (Askew, 2014). He painted and printed on top of compositions based on his 1960s work created abstract shapes and reflections. By bringing back subject matter from his early works, Lichtenstein acknowledged the role his own art played in mass visual culture (Bilske, 2004). This series bridges his iconic midcentury pop art with his later more surreal and abstract works.

To Roy Lichtenstein, the reflections were “just an excuse to make an abstract work” (Askew 2014). To the casual viewer, the reflections are a clever compositional technique. The more time you spend with Reflections on Conversation, however, the more apparent both Lichtenstein’s humour and critique become.

To the more serious distinction between viewer and subject, Lichtenstein’s wit is as apparent as his technical prowess.

Lichtenstein’s title, Reflections on Conversation creates a meaning: reflections on Conversations, a literal look at reflections atop a painted conversation, and reflections on our own conversations. The reflections obscure the mouths of the pictured couple forcing the viewer away from the subject. Instead of simply observing we are voyeurs. The feelings of the pair are indistinguishable from outside, what could be anger could also be sadness or passion, and their words are hidden behind the reflection. Unlike a much of Lichtenstein’s iconic works, this piece has no caption nor dialogue. Instead, as we look in, our own conversations play out behind the painted glass. Reflections on Conversation asks us to reflect on ourselves, and the visual culture we immerse ourselves in. I, for one, have some thinking to do.

Cecilia Soukup

As we dive into the concept of ‘reflections’ we need to focus on deeper issues than just reflective objects in art that are used to capture a different view. Yes, they can be beautifully depicted in hyper realism showing off an artist’s skill, but when they capture a whole new perspective, they add more than just visual interest, they contain the theme of a work. This is true for Francis Bacon’s portrait of his petty criminal lover that captures the internal conflict of hyper masculinity and sexuality.

At first glance you may find this work a bit dizzying. The central figure does indeed seem to rotate in a very abstract way in a rolling chair. One half of his body morphs into the other at a completely different angle creating the interesting, unnatural, collapse of his left ear to his right shoulder. He seems almost split in half as if he is also being pulled into different dimensions, but the lines continue around and down despite that break. This circular movement is mimicked by several swift swipes of white paint in the same direction near the figure. As well as an almost halo effect at the top and the circular blue carpet that frames the composition every aspect of the work echoes the spiral movement.

Despite the figure holding a hand mirror, he turns away from it and his reflection is captured in the television set behind him. Because of the morphed figure’s body, we are relying on the reflection to see his face, which contrasts with the body and is broken up and stretched instead of collapsed and warped.

George Dyer, the sitter for this portrait as well as many of Bacon’s other works, is easily distinguished by his impressive profile, notably his prominent nose. He is shown in a stylish beige suit with his hair perfectly slicked back. However, his reflection shows him broken and spiraling with hints of red and dark tones that show fresh wounds and bruises all

over his face. These could represent the history of abuse he suffered that shaped his violent reality. Dyer and Bacon had a very physically, mentally, and emotionally abusive on-and-offagain relationship until Dyer followed up on his threats and committed suicide. Dyer, much like Bacon, struggled with his sexual identity and how to understand himself as a homosexual man in a hyper masculine society. Dyer was outwardly a “tough guy” or a “thug” with a criminal record of petty crimes to back it up. This is why we see the “real” Dyer quickly captured in an unexpected reflective source, almost as if his tough guy mask has accidently slipped and offered us a glimpse of his internal conflict. His external facade didn’t allow Dyer to be truly himself. This portrait perfectly reflects the struggle Dyer had with presenting as a hyper masculine man, while feeling internally conflicted and tormented by his identity and how it didn’t fit into the society he lived in. Bacon used reflection in this work to show the real face of his beloved and illustrate the conflict he felt between his hypermasculine facade and the hurt, emotional, and loved person he truly was.

Anastasia Soutos

The most captivating aspect of Pieter Claesz’s still life, Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball, is undeniably the reflective glass ball situated at the edge of the table. The almost hyper realistic depiction of the glass ball demonstrates Claesz’s mastery of painting and the famous baroque style still life. Vanitas is a Latin word meaning “vanity” or “futility” and was used in Dutch 17th century painting to describe a type of still life painting that used symbolism relating to death and provided an analogy of human mortality. In Claesz’s Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball, he uses the reflection of the glass ball to challenge the idea of his own mortality.

The whole of Claesz’s work functions on the sensation of fragility and symbolism pertaining to human mortality. Compositionally, Claesz creates a feeling of tension through the placement of the glass ball near the edge of the table, threatening its fall and shatter, the tipped over wine glass and even in the bow precariously balancing on the violin. Everything hints at a sudden end, heightening a sense of anxiety in the viewer along with the theme of temporality. Symbolism of mortality is littered throughout the painting with a watch in the foreground and human skull and burnt out candle in the background. Additionally, Class includes the violin as an allegory of the human condition as, like music, there is a beginning and an end to each life.

Claesz’s mortality is included in his reflection in the glass ball. Materialistically, the glass ball alludes to its fragility and likely end, perhaps hinting at Claezs’s own inevitable end. Claesz positions the glass ball, and the position of his reflection, to be opposite the human skull- opening up two interpretations. The first being that he will also die and eventually become like the skull on the table, and the second being that, in spite of death, his legacy will become immortal through the reflection of the glass ball.

Picture it: 1,500 shiny mirror balls cover the lawn outside one of the most prestigious art exhibitions in the world. A woman wearing a golden kimono stands by the mirror balls with a sign that reads: “NARCISSUS GARDEN, KUSAMA” and “YOUR NARCISIUM[sic]

FOR SALE, $2.” Passersby walk through the balls, pick them up, toss them between each other, and watch the woman as she sells them–until the police arrive and attempt to stop her.

Narcissus Garden (1966) by Yayoi Kusama is an artwork completely made of reflections. An installation of 1,500 mass-produced plastic mirror balls, each the size of a fortune-telling crystal ball, Narcissus Garden is an intriguing piece of contemporary art that calls into question the roles of the artist, viewer, and environment in the creation of meaning.

Kusama was born in 1929 in Matsumoto, Japan. She moved to New York City in 1957, where she began producing contemporary art of various mediums in a quest for fame and recognition amidst the white, male-dominated American art scene. She was able to establish connections with the European art world, including Lucio Fontana, an Italian contemporary artist, and Renato Cardozzo, his art dealer. It was through these connections that Kusama gained permission to display Narcissus Garden outside the 1966 Venice Biennale. As attendees picked up the mirror balls, they were confronted with their own narcissism–they were looking at a reflection of themselves and their presence at this elite event.

The market-like aspect of the original 1966 installation of Narcissus Garden has led to many interpretations of the piece simply critiquing the elite commercialization of art. Recent scholars have now expanded the interpretation of Narcissus Garden to discuss Kusama’s self-marketing via photography of her with the art as part of the installation itself.

Photographs, organized by Kusama, center on her and her interactions with the mirror balls. Later in the week of the 1966 biennial, she wore a red unitard and lay down amongst the balls as if they were spilling down a hill. These images have now become an iconic part of the public imagination of Kusama, portraying her as eccentric, playful, and interactive. These photographs, when contextualized with the installation, Kusama’s other works, and the time period of the 1960s, all point to a larger significance for Narcissus Garden.

Kusama has been characterized (and even caricatured) as obsessed with her own image and fame. A persona studies analysis of Kusama by SooJin Lee from 2015 argues the artist’s persona can sometimes overtake the artwork itself. Lee highlights the 1960s context of Kusama’s art and how her concern with fame more likely stemmed from her identity and social status rather than narcissism. Her appearances dressed in kimono were critiques of the Orientalist fantasy that dominated media at the time as WWII, the Korean War, and Vietnam War centered Asian countries in the American mind, Lee further argues.

Kusama had a complex set of messages she wanted to communicate and sophisticatedly combined these concerns through both her physical artwork and her persona, reflecting off one another. Thus, Narcissus Garden offers an interesting look into how artists create meaning. Our reflections on the mirror balls directly present us with our own narcissism; however, we also see the artist’s narcissism, the narcissism of the elite art market, and the struggles of a marginalized figure in the 1960s. Or, we simply see a beautiful pool of floating plastic mirror balls. Either way, Kusama continues to be one of the most interesting, influential, and intelligent artists working today.

Bibliography

“Not to be Reproduced”, Giuliana Angotti

“Not to Be Reproduced, 1937 by Rene Magritte.” n.d. René Magritte. https:// www.renemagritte.org/not-to-be-reproduced.jsp.

“La Reproduction Interdite - Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.” n.d. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. https://www.boijmans.nl/en/collection/artworks/4232/lareproduction-interdite.

Sisters Series: Experiments in Familial, Feminine Intimacy, Zoe Davis

Whitfield, Zoe, “Brianna Capozzi’s Generation-Spanning Portraits of Biological Sisters,” AnOther Magazine, September 4, 2024, https://www. anothermag.com/art-photography/15841/brianna-capozzi-photographersisters-book-interview-idea.

Whitfield, “Brianna Capozzi’s Generation-Spanning Portraits of Biological Sisters.”

Baron, Geraldine, and Salome Oggenfuss, “Casting Brianna Capozzi’s New Photography Book + Exhibition Sisters,” Casting Double, Accessed October 30, 2024, http://castingdouble.com/sisters.

Baron, Geraldine, and Salome Oggenfuss. “Casting Brianna Capozzi’s New Photography Book + Exhibition Sisters.” Casting Double. Accessed October 30, 2024. http://castingdouble.com/sisters.

Brennan, Orla. “Brianna Capozzi’s Portraits Celebrate the Power of Sisterly Bonds.” Dazed, September 11, 2024. https://www.dazeddigital.com/artphotography/article/64582/1/brianna-capozzi-idea-sisters-portraits-photobook.

Capozzi, Brianna. Sisters. 1st ed. Soho, London: IDEA, 2024. https://www. ideanow.online/store/Brianna-Capozzi-Sisters-p696502129.

“Narcissus”, Sierra Manja

Zucker, Steven, and Beth Harris. YouTube, YouTube, 2011, www.youtube.com/ watch?v=JrTsNuUQXzU.

“Metamorphoses (Kline) 3, the Ovid Collection, Univ. Of Virginia E-Text Center.” n.d https://ovid.lib.virginia.edu/trans/Metamorph3.htm#476975714.

“Cloud Gate”, Lauren Nash

Kapoor, Anish. n.d. “Anish Kapoor: Cloud Gate.” https://anishkapoor.com/110/ cloud-gate-2.

O’Connor, Kelsey. 2024. “The Bean (Cloud Gate) in Chicago.” Choose Chicago. July 18, 2024.

https://www.choosechicago.com/articles/tours-and-attractions/the-beanchicago/.

Our True Reflections, Cecelia Soukup

Tête, L’Art En. 2021. “Francis Bacon and the Portrait of George Dyer.” L’Art En Tête. August 27, 2021. https://l-art-en-tete.com/2021/08/27/francis-bacon-andthe-portrait-of-george-dyer/.

Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza. n.d. “Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror.” https://www.museothyssen.org/en/collection/artists/bacon-francis/portraitgeorge-dyer-mirror.

“Art | Francis Bacon.” 2024. November 15, 2024. https://www.francis-bacon.com/ art.

Reflections in Conversation, Katrina Raab

Tate. n.d. “‘Reflections on Conversation‘, Roy Lichtenstein, 1990 | Tate.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lichtenstein-reflectionson-conversation-al00367.

Tate. n.d. “‘Reflections on Brushstrokes‘, Roy Lichtenstein, 1990 | Tate.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/lichtenstein-reflectionson-brushstrokes-p12128.

Narcissus Garden, Clare Yee

Sullivan, Marin R. “Reflective Acts and Mirrored Images: Yayoi Kusama’s Narcissus Garden.”

History of Photography 39, no. 4 (December 2015): 405-423. doi:10.10 80/03087298.2015.1093775.

Lee, SooJin. “The Art and Politics of Artists’ Personas: The Case of Yayoi Kusama.” Persona Studies 1, no. 1 (2015): 25-39. doi:10.21153/ps2015vol1no1art422.

William and Mary Studio Art Major

Minimum Required Credit Hours: 37

Core Requirements

ART 211 - Drawing and Color, and ART 212 - 3D Design: Form and Space

ART 461 - Capstone I

ART 462 - Capstone II

ART 463 - Capstone III

(2) 200-level Art History courses at, or above ARTH 230

(1) 300-level Art History course at, or above ARTH 330

*17 Additional Credits in Two or Three Dimensional Focus Studies

William and Mary Art History Major

Minimum Required Credit Hours: 33

Foundational Courses

(3) 200 level courses at or above ARTH 230 to ARTH 299

ART 211 - Drawing and Color, or ART 212 - 3D Design: Form and Space

Core Requirements

ARTH 331 - The Curatorial Project

ARTH 333 - Theories and Methods of Art History

ARTH 493 - Capstone Seminar

*9 Additional Credits at or above ARTH 330 and 1 Elective Course