12 minute read

STaR SHOTS DST Group leans forward

from ADBR May-June 2020

by adbr5

STaR SHOTS

DST targets high-impact technological problems

Advertisement

As old strategic certainties become increasingly less certain, and our part of the world becomes more contested, Australia faces some problems which can only be confronted with serious science.

Take space for example. The ADF and the Australian community rely on space-delivered capability, from communications and surveillance to TV broadcasts and Google maps. Yet that means overwhelming reliance on other people’s satellites which, at crunch time, may be degraded or simply unavailable.

Australia is acquiring new submarines and antisubmarine warships, but our vast ocean surrounds still provide a haven for other people’s submarines which, in time of conflict, could halt fuel imports and exports of everything we sell.

And there’s more: while the COVID-19 pandemic has delivered a small taste of what may lie ahead, the ADF has never had to operate in a contested chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear (CBRN) threat environment.

To enable future ADF operations in these domains, the Defence Science and Technology

BY MAX BLENKIN (DST) Group has come up with eight of what it calls STaR (Science, Technology and Research) Shots, a term inspired by the technological challenge in putting humans on the moon half a century ago.

The new DST Strategy – entitled More, together: Defence Science and Technology Strategy 2030 – was released in May. It intends to concentrate strategic research on a smaller number of specific and challenging problems, up there with the scale and impact of the world-leading Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN).

Chief Defence Scientist Professor Tanya Monro told ADBR this is a significant shift that DST cannot achieve on its own. “The problems Australia needs science and technology for in defence are much bigger than DST alone can solve. I am not going to be able to grow my workforce anywhere near enough. To do it we need to harness the capabilities of Australian industry and Australian universities. “We need to much more effectively communicate the challenges and much more effectively partner.

“Partly it’s also about getting better at transitioning things out of DST – not holding on to things just because they were invented

Priority number one: delivering efficient spacebased communications, surveillance, navigation and positioning capability without reliance on international assets. SMARTSAT

Professor Tanya Monro, DST Chief Defence Scientist: ‘We need to much more effectively communicate the challenges, and much more effectively partner.’ DST

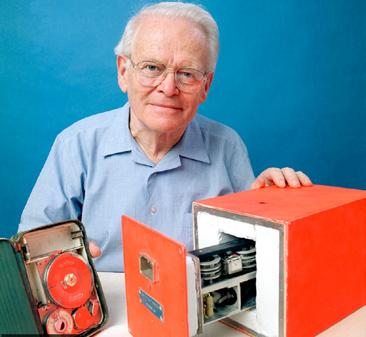

DST’s proud history includes development by David Warren in the 1950s of the iconic Black Box flight data recorder. DST here but actually seeing our success as them being ‘used’ and advanced by others.”

Professor Monro says this is a big cultural shift that will take a decade.

DST is Australia’s second biggest publicly funded engineering and scientific research institution after the CSIRO. DST has about 2,100 personnel with an annual budget around $600 million against CSIRO’s 5,000 personnel and $1.6 billion. DST does its work at eight locations, with the main sites Edinburgh Parks in Adelaide and Fisherman’s Bend in Melbourne.

Australia has a rich history of defence science dating back before World War I when the Inspector of Explosives was called to troubleshoot production of .303 ammunition. Along the way, Australian defence scientists developed aircraft for WW2, participated in nuclear tests, and launched Australia’s first satellite.

One of the most recognised achievement remains the aircraft Black Box, or flight data recorder, developed by defence scientist Dr David Warren in the 1950s. Descendants of his technology are now aboard commercial and military aircraft around the world.

But much of what DST does isn’t about developing all-new defence capability. It’s about meeting particular technical challenges, such as developing anechoic tiles for the Collins submarines, or getting the best out of existing platforms and systems – fatigue testing of aircraft to determine lifespan for example.

It’s also about responding to emerging issues at short notice. DST is now front and centre of Australia’s response to COVID-19, conducting trials on virus survivability and working with universities on pandemic modelling. Notably DST, in collaboration with Adelaide company Axiom Precision Manufacturing, performed the rapid development, prototyping and production of face shields for Australian medical personnel.

That was possible because DST and Axiom engineering teams knew each other and could ramp up quickly, Professor Monro said. Axiom

has previously produced components of Collins submarines and electronics for improvised explosive device (IED) countermeasures devices supplied to the Afghan National Security Forces.

Professor Monro says the new strategy designates a set of desired, priority capability outcomes not currently possible with existing technology and for which new science and technology are needed.

“These are things that have come through deep reflection on the strategic environment but also a lot of conversation with capability managers about what they see coming down the pipe and what they are going to need in the future,” she said. “This will engage universities and industry, ranging from the large primes to SMEs, a rich source of innovation.

“My very clear view, which has come through a lot of thinking and listening and learning, is that we are spread a bit thin … and that we need to have greater scale and focus on things only we (DST) can do.”

She added that Australia has a “fantastic R&D sector, majority-based in universities, unlike other five-eyes countries where R&D is more commonly based in industry.”

Professor Monro sees an expanding role for small innovators, SMEs and entrepreneurs in addressing the emerging challenges. She said DST’s role was to generate and translate knowledge for impact in the ADF and for Australia’s benefit.

Some of that comes from DST researchers working directly with the ADF, “but much of it is delivered through industry,” she said. “We have strategic alliances with all the big defence primes and have very clear areas of focus with them. A lot of our support inside Defence from our innovation program goes to SMEs, and that’s something I am looking to grow.”

Professor Monro said she saw significantly more innovation potential from those SMEs, though some were under pressure at the moment. “We can do more,” she said. “I am really keen to bring SMEs closer to our activity.

“That is an important thing about this new strategy,” she added. “We are developing industry pathways for the transition from the start in each of the STaR Shots. We are inviting companies big and small to join the conversation and help us develop the implementation plans.”

DST isn’t approaching its STaR Shots with any particular solution in mind. Professor Monro said she wanted this to be technologyagnostic, not considering a particular challenge and assuming it can only be solved by one type of technology.

“By articulating the problems we are trying to solve and not pre-judging what technologies will solve them, we actually open up the aperture a lot more to people with good ideas, or suggesting unexpected things, or allowing us to exploit converging technologies to create new technologies,” she said.

A digital render of the Equitorial Australia launch facility in the Northern Territory, one of two Australian space launch sites under development. NT GOVT

This isn’t just a new strategy for DST group. It’s the Defence Science and Technology strategy for the whole of Defence, with the Chief Defence Scientist taking an additional role of Capability Manager for Innovation, Science and Technology across Defence.

STaR Shot number one – the one at the top of the list, not necessarily the highest priority – aims to provide “resilient global communications, position navigation and timing (PNT) and Earth observation capabilities direct to ADF users, enabled by a low earth orbit (LEO) SmartSat constellation”.

Without space-delivered communications, navigation, surveillance, and positioning, the ADF would be at a significant disadvantage. “Our heavy dependence on space capability allows us to punch well above our weight, but it’s also a potential weakness,” wrote Australian Strategic Policy Institute senior analyst Dr Malcolm Davis.

“If we lose access to space, our military won’t be able to undertake modern information operations. Our reliance on space could be an Achilles’ heel in a conflict, and our adversaries could try to exploit that vulnerability.”

The problem is that almost all this capability is delivered through other people’s space assets. Military communications come mostly through the US WGS satellite constellation of which Australia is a partner, and through a hosted payload on the Optus C-1 satellite which was launched in 2003 and is now well past its expected life.

SATCOM works really well, delivering reliable highbandwidth comms to meet the insatiable defence appetite for data. But in time of crisis, this could quickly become congested, degraded, or unavailable. The ADF does have a communications alternative through an HF system which will soon undergo an upgrade through the JP9101 EDHFCS project.

But positioning and navigation comes by way of the US GPS satellite constellation, again super reliable but also likely to be a prime target at the outbreak of any future conflict. It’s not for nothing that others have developed their own sovereign satellite navigation capabilities – China with Beidou, Russia’s Glonast, and the European Galileo systems.

Surveillance – like navigation and positioning – is as much a civilian issue as it is for the military. GPS delivers vital civil services, from navigation to agriculture and mining. For civil and military surveillance, Australia relies on multiple providers, none of which we could really call our own. This isn’t always to our advantage – for example other people could see imagery of our crop yields before we do, and there were no satellites available for dedicated monitoring of the recent 2019/2020 bushfires.

So what to do? Australia needs its own satellites along with a launch capability. Neither is far beyond reach, tied in with the national civil space renaissance marked by formation of the Australian Space Agency in 2018.

Two commercial launch sites are in development: the Equatorial Launch Australia facility in the Northern Territory, and Southern Launch in South Australia. However, at crunch time, launches can be just as easily conducted from an Outback paddock.

DST is a core partner in the new SmartSat Cooperative Research Centre (CRC), launched last year to unite research organisations, universities, primes, and SMEs in the development of new satellite capabilities. With a government contribution of $55 million, SmartSat has total research funding of $250 million.

Professor Monro said this was an exemplar of what DST is trying to do. “We have taken a defence

The Compact Hybrid OpticalRF user terminal know as CHORUS, a collaboration between DST and SmartSat. SMARTSAT

DST is using the Slocum Glider, a small commercially available, undersea vehicle capable of long-term monitoring of oceanographic parameters, to develop, assess and demonstrate cost-effective approaches to unmanned undersea surveillance for the ADF.DST

problem, we have taken some defence money, and we have been able to align agendas and resources and leverage investment from industry and from government and from universities to the same end. That’s exciting.” Professor Monro said developing a sovereign satellite and launch capability was well aligned with the national resilience agenda. “This technology step to moving to a constellation of what can be self-healing, reconfigurable multi-purpose small satellites, is something that breaks down some of the hurdles that have kept Australia out of space,” she said.

“It is a much lower cost point and you can adapt it as you go. It’s also a leap ahead in terms of capability. The intent is to have the user on the ground to be able to get information directly from the cloud without having to go through ground stations.”

Defence has already taken significant steps. In May, it signed an agreement with Queensland company Gilmour Space Technologies to develop rocket technology to launch small satellites. The Office of National Intelligence has also issued a request for tender for a provider of research and engineering services for development, test, launch and operation of a prototype smart satellite.

Also, in May DST announced its first collaborative venture through the SmartSat CRC to research integration of laser-based optical and radio frequency communications technologies in a single SATCOM user terminal. Known as the Compact Hybrid Optical-RF User Segment – or CHORUS – this venture aims to address congestion in the RF spectrum by developing a capability for secure laser communication to and from satellites.

The STaR Shot for remote undersea surveillance says the challenge is to develop above and below water sensors, information processing, communication, and data fusion systems to provide remote surveillance of undersea environments over Australia’s area of maritime responsibility.

The obvious answer is autonomous vessels. Professor Monro said she often had to restrain her enthusiastic and capable scientists because they jumped to a solution.

“It’s easy to think what we need are autonomous vessels of this or that kind. I am sure autonomous vehicles will play a critical role in any solution,” she said. “But there might be some clever things we can do with other forms of sensing technology with other forms of information technology that might still give us a solution on how do we surveil to protect Australia’s interests.

“It’s a good problem,” she added. “Again I am always just forcing this discipline to not assuming it is going to be this or that technology. Paint the problem.”

Professor Monro notes that autonomous capabilities feature in a number of the STaR Shots, with the intent of keeping humans out of harm’s way and maximising the ability of a small defence force to operate over a vast area.

Constellations of small military satellites and a capability to spot submarines far out in the Indian or Southern Ocean might seem just a little farfetched, even in this era of strategic uncertainty. However, Professor Monro says all of these STaR Shots came together when it was decided that the focus really needed to be prevailing in a contested environment.

“Once you take that central concept, which is very powerful in the current strategic context, it’s ... no longer about discrete named operations. This is about that grey zone of increased global uncertainty. We need to be able to protect Australia’s interests.”

Professor Monro came to DST in March last year – the first female to hold this position – succeeding Dr Alex Zelinsky. Her appointment followed a distinguished career in academia, researching optoelectronics in Australia and the UK. She attributes her interest in science to an inspirational high school teacher, and that has translated into a passion for STEM and lifting the national level of STEM literacy.

This isn’t just about getting more students into research labs. “I want us to have a society where more of our decision makers can look at evidence and make evidence-based decisions and understand and interpret data,” she said. “I find it quite terrifying how poor we are culturally in that regard and that it is acceptable in many social contexts for people to say they are no good at maths. I have never heard anyone say they couldn’t read and feel proud of that. There is some weird societal thing there.

“We can change it, but we have to start young. We have to somehow blast out of the water the idea that science is hard and maths is hard, because it does us a real harm.”