13 minute read

Remote Peaks

Text & Photos: Emma Svensson

So close but oh so far away

Advertisement

What do you do when things don't go according to plan? You think again. Alpine climbers Emma Svensson and Anton Levein found challenges closer to home in a year when nothing went according to plan.

Emma Svensson is an alpine climber and photographer. Three years ago, she decided to climb the highest mountain in every country in Europe – in one year! She set a new world record with this feat and started an enduring love affair with the mountains.

We hop off the bus in Kvikkjokk and are immediately attacked by a swarm of mosquitoes. I don't think I've seen so many mosquitoes in my entire life – and I'm somebody mosquitoes love. We shelter inside the mountain station for a while before the adventure begins for real; me and my friend Anton Levein will head into the Swedish wilderness to climb all of the country's 2000-metre peaks.

In each 38-litre daypack, we've packed everything we need for the next twelve days in Sarek: climbing and camping equipment, food and clothing. We carry 16 kilos each, and on our feet, wear trail shoes. Neither of us has been to Sarek before, and we don't really know what to expect other than an exciting adventure. This is exactly what we need, especially with all our other plans cancelled and the world upside down.

We start by following the Kungsleden trail towards Pårtestugan before turning off at the sign towards Pårek. This puts us on the trail towards the Pårte massif and the two 2000-metre peaks, Pårtetjåkkå and Palkattjåkkå. After a few kilometres, we head west and instead of taking the well-marked trail, we follow a nearly invisible path. We lose it a couple of times and get lost but manage to find it again.

The mosquitoes are everywhere. Mostly on my forehead, right where the cap ends. I count twelve mosquito bites on the forehead after the first day and close to thirty-five on the rest of my body.

We can't stop for a break without being eaten alive, so we walk continuously for many hours. We lose track of time – it's the end of June, and the sun never sets. We've heard warnings that there's more snow than ever in the Swedish mountains and that the streams are flowing high and fast. After 18 kilometres, when it's almost midnight, we set up camp by a nice lake. We eat our freeze-dried dinner, crawl into our sleeping bags and don't wake up until 9 o'clock the following day.

The second day begins with the first of many fordings. Early on, we realised that we would probably have wet feet for two weeks and since we wanted to minimise the load, didn't bring any extra shoes. Instead, we go straight through the water in our trail shoes. We do, however, wear Sealskinz waterproof socks that keep the water off and our feet warm, even though the water is knee-high.

It takes longer than we expect to get to the first peak, but after 15 kilometres and 1400 metres of elevation, we find ourselves at the top of Pårtetjåkkå. Technically speaking, it's Sweden's easiest 2000-metre peak to climb. The way up is hiking on pebbles. We're met with cold winds at the top. Now we have to traverse the ridge that will take us to Palkattjåkkå.

The climbing is straightforward: we free climb without ropes, up and down over other peaks along the way. The ridge is sometimes narrow; the rocks unstable. We do two rappels along the way. When we're 100 metres from the top, we find a flat piece of glacier to pitch the tent on. You'd be lucky to find a better campsite than this at 2000 metresabove-sea-level in the Swedish mountains. We quickly fall asleep after 15 hours of climbing and almost 2000 metres of altitude in one day.

We start the third day with our first and only argument: to descend along the Palkattjåkkå ridge we have to climb down on loose rocks and at one point have to rappel down. The problem is that there's nothing good enough to rappel from. Finally, we find a boulder that will have to do. It's slightly larger than a pillow and I'm scared to death. Will it suffice?

It does, and we continue down a glacier, into a valley. We wade across numerous streams and spend a lot of time finding the right place to cross as the water is high. It's a never-ending trek and the relentless mosquitos wear us down. We set up camp by a river, halfway to the Sarek massif.

Day four begins with more wading and then continues up and down glaciers, through swamps, bushes, and rugged terrain. As we approach the Sarek massif, we find an emergency shelter where we take a break to escape the mosquitos for a while. We decide to spend the night there as we're mentally drained by the constant buzzing around our faces. We have to set the alarm for 4 am, but it's worth it.

The fifth day is one of the best of the adventure. The weather is perfect, and we're about to climb all four 2000-metre peaks in the Sarek massif. We start the day by crossing Smajlatjåkkå, a wide stream with a powerful current. The summer bridge hasn't been set up yet and halfway across, we have to turn back. We find another place to cross that feels safer. The water reaches our thighs and splashes up to our waists. It's freezing cold but we're so focused on crossing the stream that we don't even feel it. Scary!

We continue up the glacier and end up just south of the southern peak. We scramble up via a ridge and after a grade II climb, reach the passage between the southern peak and the Buchts peak. Here we leave our backpacks, unpack ropes and climbing equipment and immediately head up the Buchts peak. We follow an exposed but short ridge and after a grade 4 crux, untie ourselves and leave the ropes behind to continue up the pre-peak towards the main peak. After reaching the Buchts peak, we return to our backpacks. After a smooth rappel down, we cross the exposed ridge and head up towards the south peak. The climb is fun and easy. From the south peak, we continue towards Sarektjkåkkå and then up towards the north peak. The traverse winds up and down along a ridge with easy grade III-IIII climbing and a couple of rappels.

Reaching the north peak, we hear thunder approaching and hurry down the glacier to set up camp down in the valley. It's not a minute too soon: in total, we've completed 25 kilometres of climbing with 1000 metres of altitude

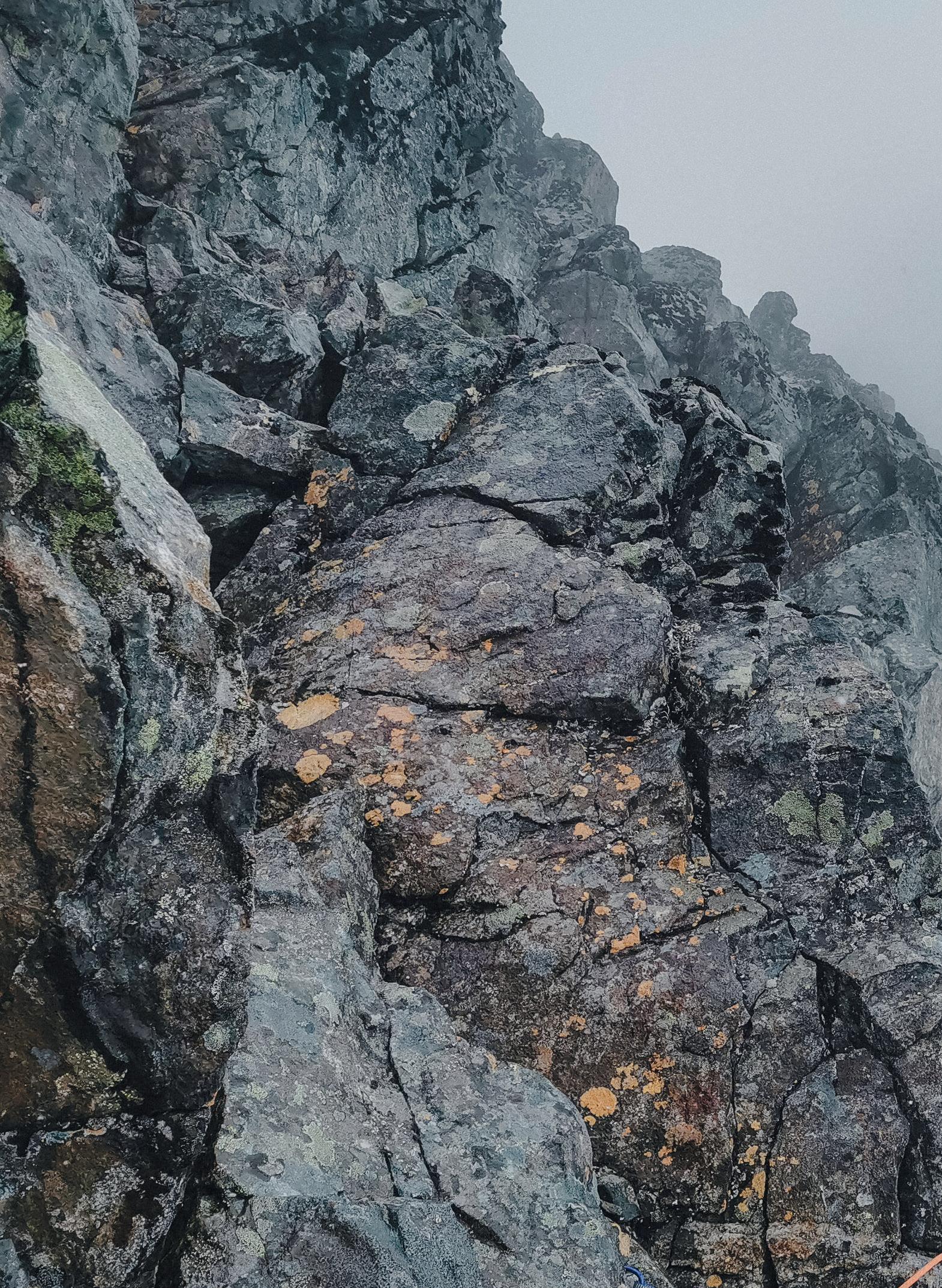

Rain, snow and zero visibility on the Nygren trail on Kebnekaise. At least the mood was good!

About Remote Peaks

2020 was the year the pandemic forced the whole world to press pause and many plans were put on hold. Emma Svensson was supposed to spend the summer in some of the world's highest alpine areas but when these summer projects were cancelled, she and her climbing partner Anton picked more-local destinations. The result was a challenging and exciting summer, trekking in trail shoes with 38-litre backpacks through Sarek National Park and climbing all of Sweden's twelve 2000-metre peaks. This is Emma's story about their Remote Peaks project.

during the day.

After the Sarek massif, a three-day hike to Ahkka awaits. This takes us across glaciers and streams, through swamps and bushlands – with a constant swarm of mosquitoes buzzing around our heads. We cover close to 53 kilometres and 2000 metres of altitude before the rain starts pouring. 8 kilometres from the foot of Ahkka, we finally reach a cabin, soaking wet. This is our chance to dry some things before it's time to climb the next peak. In a blizzard. When we head out again around two o'clock in the afternoon on the ninth day, it's the coldest July day in decades and with the windchill feels like -10° at the peak of Ahkka.

My feet are stiff with cold in my trail shoes after two cold wades. We hike across snowfields and the heat never returns. Anton has to bite the bullet, and I sit with my feet in his armpits for a while. The warmth and feeling come back and we continue. Winter reigns supreme at the top, a frozen world sprawling out in front of us. We fight our way up in deep powder snow, balancing as we traverse the narrow ridge between the two peaks. There's an old, frozen, fixed rope to hold on to and we're grateful we have microspikes on our shoes and ice axes in our hands.

It's three o'clock in the morning when we finally cross the bridge that links to the Padjelanta trail. We're completely exhausted when we set up camp on a patch of grass in the middle of the trail. For three hours, we've bushwacked our way through a swamp, bushes and trees so dense that we practically have to claw our way through. It's the worst section of the whole project.

When we wake up, we only have a few kilometres to the boat that will take us to Ritsem, but I can barely walk: with tendonitis in my heel, I scream with pain as I put my shoes on. I then have to limp the long and painful kilometres to the bridge at Änonjalme.

At this point, we've finished the first stage of the project, two days quicker than planned. This was especially lucky because, by this point, we had to ration our food. We already knew from the beginning that we were a bit short on food, as we chose to pack light. We averaged 1500 calories per day, which meant a severe deficit as we were on the move at least 12 hours a day. Arriving in Ritsem, we buy pizza, chocolate, crisps, and stuff ourselves on the bus journey back to Kiruna.

In Kiruna, we get to rest for a couple of days and this rest is sorely needed as I can barely walk by this point. But it doesn't get much better before it's time to leave again. This time for Kebnekaise! But I don't give up and change into hiking boots for more support around my feet. The view across Vistas valley

The approach to Björling’s glacier on Kebnekasie – one of the rare occasions during Remote Peaks where Emma and Anton actually hiked a trail.

We're set on taking the eastern ridge up to the north peak, but it's raining and snowing and visibility is poor, so we take the Nygren trail instead after crossing the Björling Glacier. I'm familiar with this one, having done it before, and this is a great advantage when the weather isn't on your side. We have zero visibility on our way across the ridge to the south peak. The whole time my foot hurts so much that I want to scream but I still have to take turns with Anton leading slippery rock sections and steep snow passages on the ridge.

We'd planned to climb the Silhuett trail for fun the next day, but I have to cancel. Instead, Anton runs up the south peak via the eastern route and back to the mountain station in 2:57 while I sit by the fire, resting my foot and eating chocolate. The day before, on our way to the top, we'd met Petter Engdahl, who came running at full speed down the mountain. What we'd seen was a world record in progress: up to the top and back down again in 1:47.

We stay at Kebnekaise for a few days before we trek to Tarfala and climb Kaskasatjåkka the following day. The weather is still just as bad and we can't see a thing: to find the trail we have to feel our way with our poles in front of us. With a little help from the GPS, we manage to navigate our way up to peak number ten.

The biggest challenge awaits us the next morning. It's six o'clock when we head out towards the southwestern ridge of Kaskasapakte. Although it's alpine grade D, it feels much more difficult under the current circumstances: poor visibility, alternating rain and snow, strong winds and hail. The rock is slippery and we're soaking wet while climbing with our heavy backpacks.

At one point, balancing is tricky and I keep bumping into stuff with my backpack. With the tent attached to it, I can't manage to get through tighter sections. I laugh at how clumsy I am with the backpack on my back, but when Anton cries out "damn, that was the scariest manouevre I've ever done", after a crux that was hard to belay, with precipices in all directions, I understand the severity of the situation. This trail is not for tourists but real climbers. It's a long day, up and down several ridges with the trail getting trickier the higher we get.

As we reach the top, the sun pokes its head out for a few minutes. We relish it more than ever and celebrate with some chocolate before heading down the western ridge. With loose rocks and having to make delicate moves mindful of our balance, it takes time. Still, we manage to pitch the tent at the foot of the mountain in the nick of time before a heavy downpour comes bucketing down. Only one peak to go!

Onwards to Vistas, a short walk of 25 kilometres over rough terrain! For the last bit, we follow a trail through Vistasvagge, which the previous week's bad weather has turned into a muddy stream. If the mosquitoes were a pain in the ass before, it's nothing compared to now. This is the worst hike I've ever experienced, but we have to keep moving, injured ankle, mosquitos and mud notwithstanding.

Arriving in Vistas, we're greeted warmly by the cabin host, who gives us each a Coke on arrival. Our plan is to climb Sielmatjåkka from here. Usually, you do it from Nallo, but there's a way up from this side as well. We trek across the moraine, continue up a glacier and an ice wall, then have several crevasses to navigate. A walk across the glacier, a steep snow wall, some easy scrambling along the ridge, and we find ourselves at the top! Now we have to get down and back again, and we've made it!

Twenty kilometres later, back in the Vistas cabin, we splash out and celebrate with noodles for dinner. We've eaten so much freeze-dried food that we can barely stomach another spoonful – we deserve some luxury.

Anton asks me if I'd do it again: I tell him I'll never go back to the Swedish mountains during mosquito season. In these two-and-a-half weeks, I've collected over 300 mosquito bites – even though I've bathed myself in mosquito repellent. No, next time I climb a Swedish mountain, it'll be in August or September when the mosquitoes are gone. Or maybe on skis during winter – there are no mosquitos in winter!

Anton enjoying the view before heading up to Sielmatjåkka’s peak