Lee Ka Sin Adelaide 1381024 Strategic Plan Making (ABPL90131_2023_SM2)

Task 4 - Strategic Plan

Lee Ka Sin Adelaide 1381024 Strategic Plan Making (ABPL90131_2023_SM2)

Task 4 - Strategic Plan

The Maribyrnong Waterfront Cultural & Creative Advancement Strategy 2023-2028 aims to transform the waterfront into a prominent art and cultural hub in Melbourne, blending Aboriginal traditions with contemporary arts, and promoting economic growth and artistic collaborations. The strategy comprises three core goals: 1) Embrace and Increase public engagement with Aboriginal culture, 2) Boost the creative industry by growing the creative cluster, and 3) Cultivate a collaborative environment that encourages artistic synergy and innovation. To achieve these goals, eight specific actions have been outlined. A detailed monitoring and evaluation plan has been developed to track the progress towards achieving these goals using a mix of qualitative and quantitative indicators. This initiative aligns with the broader state and local strategies, aiming to revitalize the Maribyrnong Waterfront while respecting and integrating the rich Aboriginal cultural heritage. Through community engagement and strategic actions, this plan seeks to make Maribyrnong Waterfront a vibrant creative precinct that contributes to Melbourne's identity as a cultural capital.

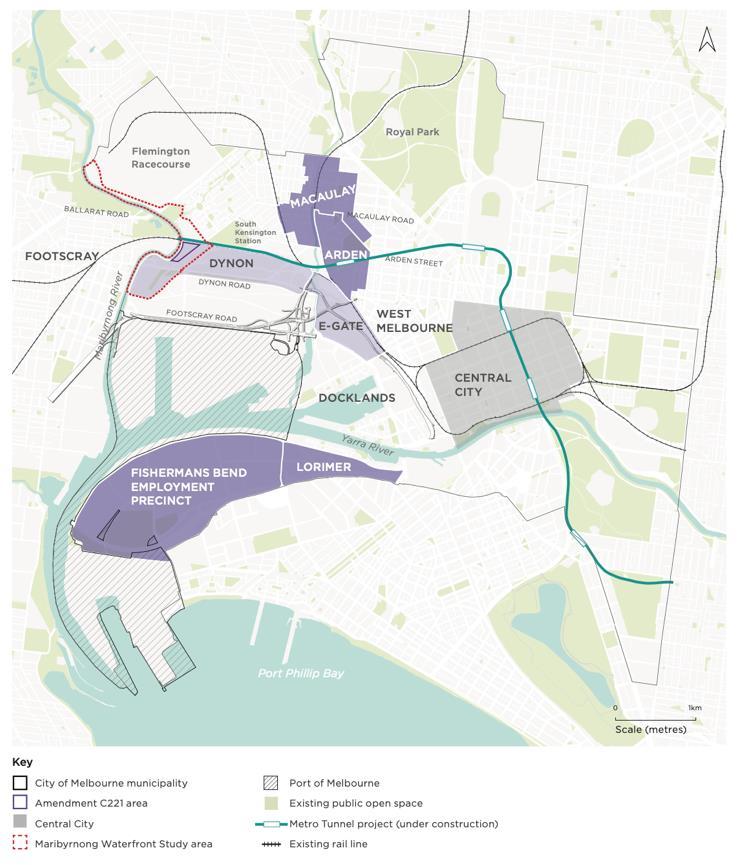

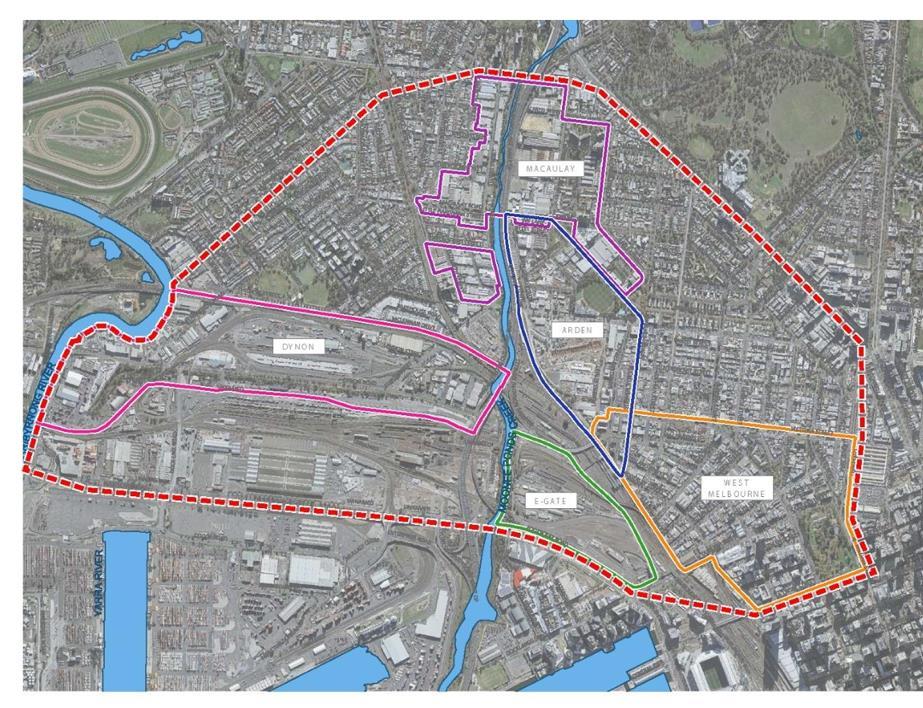

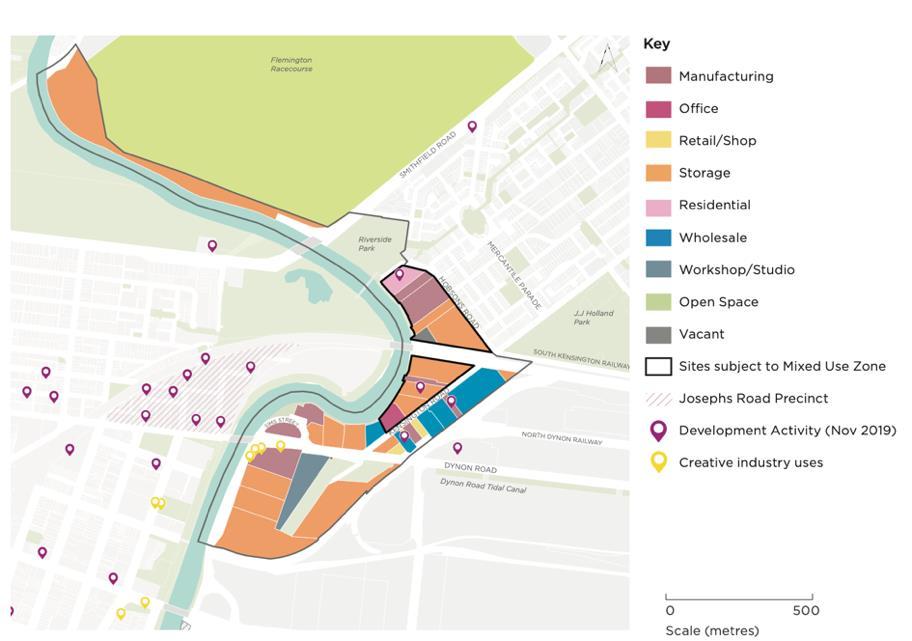

The Maribyrnong Waterfront site, situated 3.5 kilometres west of Central City, aligns with the City of Melbourne’s boundary along the Maribyrnong River. This industrial precinct is undergoing growth and transition, encapsulated by established industries and numerous major urban renewal areas and infrastructure projects.

Historically, the site near the Yarra and Maribyrnong rivers' confluence has been significant for Aboriginal people, cultures, and traditions.

26,000 years ago

Aboriginal occupation of the Melbourne region begins, as confirmed by archaeological evidence.

Pre-colonial period:

1850s-1860s

The area starts transitioning into an industrial zone to support the growing city of Melbourne. Establishment of factories along the Yarra and Saltwater Rivers.

Aboriginal people of the East Kulin Nation inhabit and care for the land, utilizing the abundant natural resources and water sources from WestMelbourne Swamp and Moonee Moonee Chain of Ponds.

1880s:

Mid-19th Century to Present:

North and West Melbourne become significant places for Aboriginal people migrating to the city for work, post their exit from missions and reserves. The area continues to serve mainly industrial and transportpurposes, with some established residential zones.

The Moonee Moonee Chain of Ponds is contained as a waterway and repurposed as a 'Coal Canal' for the Victorian Railways.

Draining of the West Melbourne Swamp begins, altering its use for railways and shipping purposes.

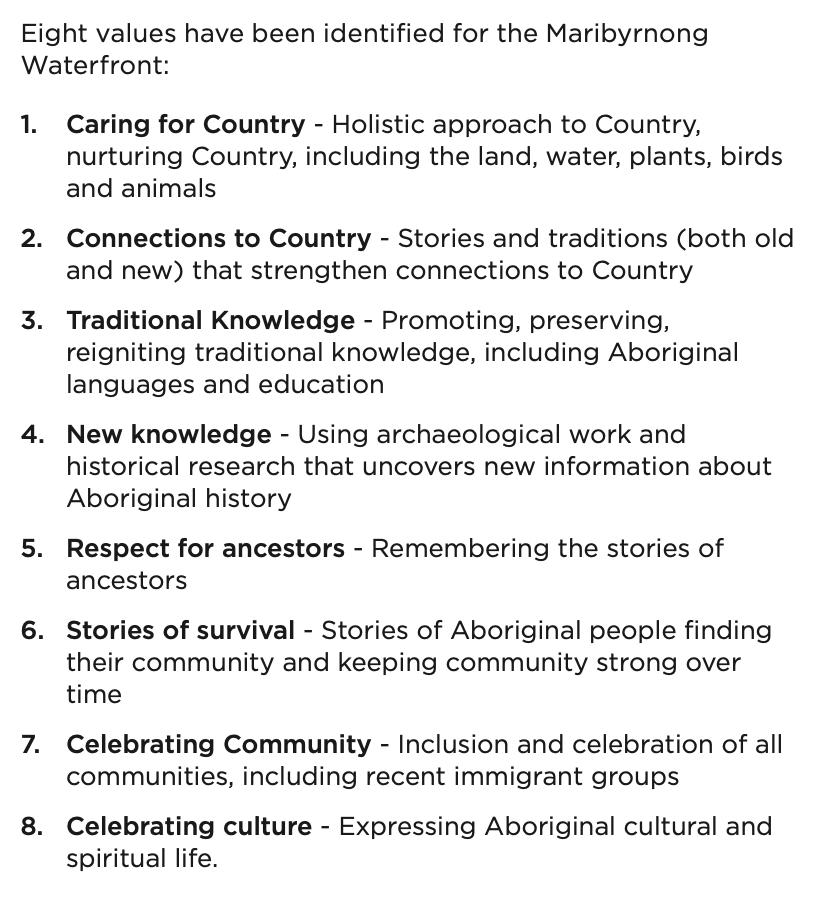

The Victorian Planning Authority and City of Melbourne conducted an Aboriginal cultural values assessment for 'North and West Melbourne', consulting with Aboriginal Traditional Owners. This assessment, supported by area's documented history and the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Register records, spotlighted the Maribyrnong Waterfront site among five strategic sites for new development, revealing rich Aboriginal cultural values spanning traditional, historical, and contemporary facets.

While Melbourne holds the title of being the creative capital in Australia (Inkifi, 2020), the City of Melbourne is investing $8.7 million boost for local artists, creative spaces, and major events, with employment growth in the art and recreation services sector (ABS, 2021).

The Maribyrnong Waterfront, once a historic industrial hub since the 1840s, now embodies creative rejuvenation with emerging creative clusters on nearby industrial land. The cluster near the river mainly spans the industrial area on Dynon Road and Footscray Activity Centre, utilizing warehouses for studios, exhibitions, or performances. Notable examples include the Footscray Community Arts Centre and River Studios.

The transition from industrial to creative use has its merits, such as providing spacious venues for studios, exhibitions, and performances. However, challenges arise in terms of infrastructure adaptation, preservation, and meeting contemporary needs. Additionally, there's a tension in preserving the legacy and historical value embedded in these industrial spaces during this transition (Chen et al., 2016). With urban development dynamics, as industrial lands evolve, they often see a rise in real estate value. This shift, while making these areas attractive venues for cultural hubs, also risks turning them into solely commercial ventures, potentially sidelining the artistic community. As Kornberger (2012, p. 4) pointed out, 'The community created value, but the property owners captured it'. Therefore, strategies need to balance between fostering cultural hubs and managing commercial development to advocate for the needs of creative practitioners.

The Council Plan prioritizes boosting the creative industry in its strategic direction, aligning with state level plan including "Plan Melbourne" and "Creative State Strategy 2025" to foster a creative milieu in Melbourne. Existing frameworks like Creative Strategy 2018-2028, Arts Infrastructure Framework 2016-21, and Public Art Framework 2021-31 underpin engagement with creative practitioners. These strategies envision a Melbourne where creative endeavors are valued, and individuals have ample opportunities to hone and exhibit their talents.

In particular, The council plan and the creative strategies both emphasize that "Aboriginal cultures are central to Melbourne’s identity," aiming to shape the city with an Aboriginal focus, in alignment with broader state directions on respecting and protecting Melbourne’s Aboriginal cultural heritage.

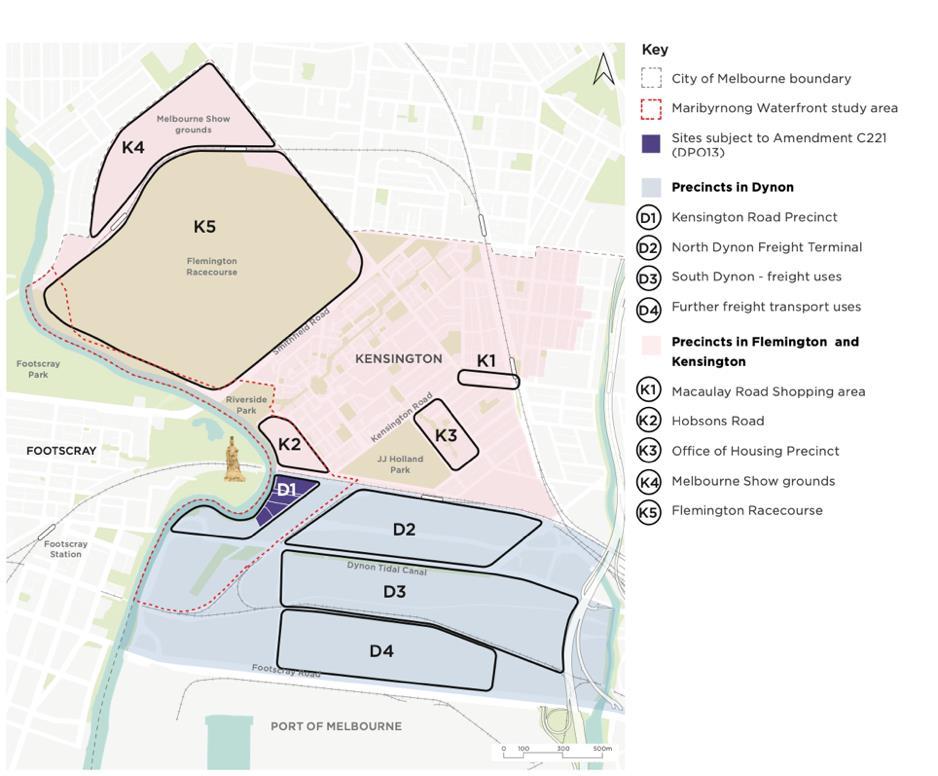

The Dynon precinct, identified as a 'potential urban renewal area,' transitions from its heavy industrial roots, with local strategies now aiming to bolster economic development in manufacturing, industry, and freight while enhancing open spaces along the Maribyrnong River within the site. Conversely, the primarily residential precincts of Flemington and Kensington have local area strategies at the site focusing on housing and accommodating new development with an appropriate scale along the Maribyrnong River, while also improving connectivity to and across the river.

Planning Scheme Amendment C221

The amendment aimed to enable mixed-use redevelopment in the broader Dynon Precinct by rezoning land from Commercial 2 to Mixed Use Zone, potentially leading to land use conflicts between industrial and sensitive uses within both the site and wider Dynon areas.

The Maribyrnong Waterfront River Valley Design Guidelines (2010)

The guidelines were developed in collaboration with Brimbank, Hume, Maribyrnong, Melbourne, and Moonee Valley councils, the Department of Planning and Community Development, Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water and the Port of Melbourne Corporation to help achieve greater planning consistency along the Maribyrnong River corridor. Future development within the site has to align with those guidelines.

Maribyrnong Waterfront – A Way Forward

The Strategic Plan highlights the site's key economic, employment roles, and its diverse uses like adaptive industrial uses, expanding creative cluster, and residential occupancy, stressing the significance of Aboriginal Cultural Values. It outlines three Future Principles to be integrated into all developments, capital works, and planning for the precinct and Dynon.

The emergence of creative clusters on the site presents a chance to advance the creative industry in alignment with state and council strategies. The transformation of the Maribyrnong Waterfront's industrial lands into creative clusters recognises urban waterfronts as catalysts for sustainable and creative development as noted by (Girard et al., 2014). An essential aspect of this transformation is the integration and celebration of the locale's Aboriginal heritage, which enriches the creative milieu. The concept of "habitus" (Beck, 2002; Lee, 1997) underscores the necessity of intertwining the locale's identity with its creative spaces, and Aboriginal heritage, described as a "mode of cultural production" by Kirshenblatt-Gimblett (1998, p. 9), can provide a unique, rich foundation for rejuvenating economies and reinvigorating abandoned sites.

Historically, waterfronts have served as cosmopolitan centres for multicultural interactions. Their unique built environments, steeped in cultural heritage, make them prime spots for tourism and economic revitalization. Following the global trend of revitalizing overlooked areas like abandoned harbour zones (Mommaas, 2004), strategically positioning creative industries within the Maribyrnong Waterfront unveils a new development perspective. This approach can attract potential investors (Kostopoulou, 2013) and foster innovative adaptation by artists and entrepreneurs, who can draw inspiration from the Aboriginal cultural values, creating a novel cultural product that enhances the city's identity. The example of Cable Factory in Helsinki and Spike Island in Bristol demonstrate the positive impact of repurposing waterfront areas for redevelopment (Kostopoulou, 2013) . By welcoming creative industries, these redevelopments not only invigorate the waterfront but also produce potential positive economic, social, and cultural ripple effects for the broader urban community.

Envisioning the waterfront as a creative hub housing art galleries, design centers, and cultural amenities emerges as a smart urban development strategy. It benefits not only residents, creative pretensioners, and tourists but also pays homage to the indigenous cultural heritage, thereby enriching the creative industry with a depth of tradition and contemporary artistry. By preserving and leveraging its historic waterfront areas, the site can bolster its creative spaces and economic capacity. This preservation not only showcases the area's distinctive character but also employs the waterfront to accommodate creative industries, catalyzing economic and employment growth to align with the strategic direction of the border context, and solidifying Maribyrnong Waterfront's position as a creative and economic hub intertwined with a rich Aboriginal cultural legacy.

Community engagement strategy fosters trust and builds a cultural resource repository, enabling an integrative approach by nurturing shared values and knowledge (Albrechts, 2006, p. 16). It ensures accurate representation of community perspectives, creating a more inclusive planning process.

The city of Melbourne has partnered with Traditional Owner Groups like the "Boon Wurrung and Woi Wurrung Cultural Heritage Aboriginal Corporation" on projects to integrate cultural heritage into urban planning, laying groundwork for further engagement activities.

While eight cultural values have been identified from previous consultations, the engagement strategy expects to gain deeper insight specifically on how art and cultural projects can promote the traditional knowledge and strengthen community connection to the country to better embrace the indigenous culture.

Hence, adopting place walking and storytelling as engagement techniques provides a culturally immersive and interactive approach to further explore the cultural connection with the site (Geia et al., 2013), for instance the Aboriginal traditions in specific area within the site.

Forums and public consultation facilitate direct communication with the creative community, garnering insights on infrastructure needs and artistic preferences. Through Melbourne's ongoing Arts Infrastructure and public art Framework, recommendations for infrastructure and thematic direction for public art projects are sought, aiming to foster a thriving hub for creative expression and industry advancement within the site.

2.3

Engaging with Indigenous artistic communities and local practitioners through Collaborative Design Workshops cultivates an innovative environment. The co-design process is empowering, fostering mutual respect. This fusion of diverse artistic perspectives is expected to gain insight on how to enrich the site's cultural ecosystem, benefiting the broader creative industry (Sanders & Stappers, 2008).

The Maribyrnong Waterfront Cultural & Creative Advancement Strategy 2023-2028 aligns with the existing Creative Strategy 2018-2028 over a five-year period, expecting for a concurrent review.

To transform Maribyrnong Waterfront into Melbourne's foremost art and cultural hub, where the depth of Aboriginal traditions and the vibrancy of contemporary arts converge, fostering a thriving economy and deeprooted artistic collaborations

Goals

1 . Embrace and Increase public engagement with Aboriginal culture

2. Boost the creative industry by growing the creative cluster

3. Cultivate a collaborative environment that encourages artistic synergy and innovation

Create a Cultural Heritage Trail along the river with interactive stations for an educational and engaging experience

A Cultural Heritage Trail can serve as an open-air museum showcasing Aboriginal culture and heritage. It provides a physical pathway guiding residents and visitors through a journey of cultural discovery. By highlighting significant sites and stories, it fosters a deeper understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal culture, making the cultural heritage more accessible and visible to the public. Studies for instance (Gantait & Sinha, 2019) have highlighted how heritage tourism initiatives like cultural trails can play a critical role in promoting indigenous cultures.

Why is it achievable?

The area's rich Aboriginal history, alongside the open space along the waterfront, provides ample opportunity for such a trail. Potential partnerships with local Aboriginal communities and organizations can contribute to the authenticity and richness of the content. Moreover, case studies like the Māori tourism development along the Whanganui River demonstrate the feasibility and positive impact of committing to cultural integrity in promoting indigenous cultures (Scheyvens et al., 2021).

Organize regular art marketplaces where Aboriginal artists can display and sell their crafts, artworks, and other cultural products

Art marketplaces not only provide Aboriginal artists with a dedicated platform to showcase and monetize their creations, reaching wider audiences, but also offer the public direct access to authentic Aboriginal art. This direct engagement fosters a deeper appreciation and understanding of Aboriginal culture. By making Aboriginal art more visible and accessible to the public, these marketplaces play a crucial role in cultural promotion. Public displays of art are instrumental in making indigenous cultures more comprehensible and relatable to a broader audience (Morphy, H. ,1999).

Why is it achievable?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visual arts and crafts report (Productivity Commission, 2021) highlight a growing demand and economic benefits for Indigenous art with total value of spending on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visual arts and crafts exceeded $250 million. The Maribyrnong Waterfront's strategic location and minimal infrastructure requirements for Art Marketplaces make it ideal for promoting Aboriginal culture through public art showcases.

Initiate a recurring Open Call program inviting submissions from Aboriginal artists for public art installation projects at designated sites within the site.

Public art enhances urban spaces, promotes community unity, and adds aesthetic value (Hall, 1994). It also advances cultural understanding and strengthens community identity as noted by the Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries, Government of Western Australia (2020).

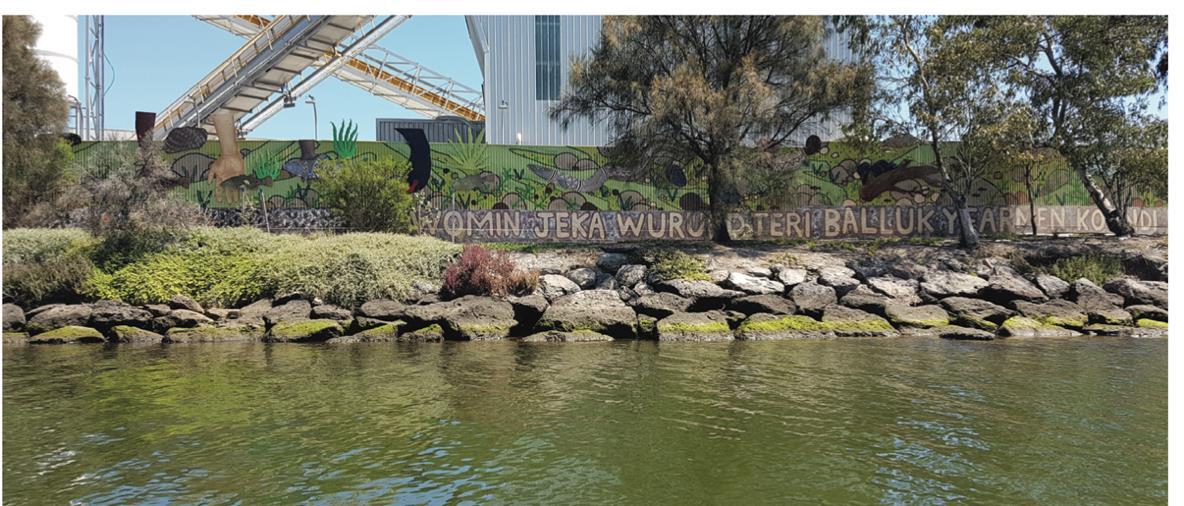

Aboriginal art installations allow the public to interact with and appreciate Aboriginal culture, serving as educational tools that bridge cultural gaps. However, the existing Wurundjeri Mural, commissioned to Holcim Ltd, demonstrates that government-led initiatives might lack a deep understanding of Aboriginal culture, risking misrepresentation (Le Roux, 2014). Public invitation to public art projects ensures respectful and accurate representation, promoting community ownership and empowerment.

Why is it achievable?

The "Creative Strategy 2018-2028" and "Arts Infrastructure Framework 2016-21" have established a solid base for promoting public art, with 47% of inner-metropolitan Melbourne residents engaging in public visual arts events according to the National Arts Participation Survey (Creative Victoria, 2022), This action along with the Maribyrnong Waterfront's unique location, aligns well with city policies to facilitate Aboriginal artist collaborations.

Streamline permitting process for development that converts existing use of warehouses into creative spaces

The concept of adaptive reuse – repurposing old structures for new functions – has gained traction in urban planning and development circles. The transformation of industrial spaces into creative hubs can rejuvenate urban areas, providing opportunities for cultural and economic growth (Geia et al., 2013). By streamlining the permitting process, the site can expedite this transformation, reducing bureaucratic red tape and making it easier for artists and creative businesses to establish themselves. This not only revitalizes underutilized spaces but also fosters a vibrant artistic community that can drive economic growth.

Why is it achievable?

The transformation of industrial spaces into creative hubs at Maribyrnong Waterfront can be more affordable due to lower initial costs and adaptable warehouse structures, attracting creative practitioners seeking cost-effective inner-city land. The existing River Studios arts studio, along with a growing creative business community in nearby Footscray, highlights the area's potential for creative reuse. Local interest and support further bolster the case for streamlined permitting processes, making it easier to convert these spaces.

Establish a Residency Program where artists can reside and work within the site for a specific duration at an affordable price

Creative residency programs have long been recognized as catalysts for artistic innovation. They provide artists with dedicated space, and resources to focus on their work, often leading to breakthroughs in their craft. Nishimura et al. (2017) highlights the significance of such programs in nurturing talent and promoting cross-cultural exchanges. By attracting both local and international artists, residency programs can enhance the diversity and richness of the creative ecosystem, making it a magnet for further talent and investment.

Why is it achievable?

Given the rising costs of living in Melbourne with median weekly advertised rent for houses increasing by 6.1% and units by 2.9% over the 12-months to June 2023 (Domain Group, 2023). There is a need for affordable accommodation, especially among artists who may have irregular income, the establishment of a Residency Program can utilize the existing industrial space to offering a housing solution tailored to the artistic community. The high demand for affordable housing among artists suggests a likely high uptake and successful implementation of such a program. Melbourne already has a vibrant artistic community and a reputation as a cultural hub, indicating a supportive environment for such a program.

Financial support is vital for emerging creative businesses, helping mitigate startup costs and space rentals. Oakley (2006) emphasizes the role of grants in easing these burdens, enabling creatives to innovate. The initiatives benefit the creative industry and have a ripple effect on the local economy as they often source materials, hire, and collaborate locally.

The city of Melbourne is currently implementing a comprehensive art grant program to support the creative industry. While 102 artists and arts organizations have received the annual funding for the 2024 batch illustrating the success of the program (City of Melbourne, 2023). This set a solid foundation for further expanding the grant program to boost the creative industry within the site.

The established creative cluster along the riverside, supported by the City of Maribyrnong Council's art and culture strategies, indicates a rich ground for artistic and cultural engagement along the riverside. However, there are potential for disconnects in growth planning across multiagency local government systems, as noted by Phelps & Nichols (2022), which poses challenges in which political discord can overshadow planning needs.

The adjacent creative developments to the site present a unique opportunity for intermunicipal collaboration between the City of Melbourne and the City of Maribyrnong. Instead of pursuing isolated initiatives or a mere replication of existing infrastructures, a collaborative approach can ensure a seamless extension of the creative vibrancy from the established hub to the Maribyrnong Waterfront site. This not only facilitates a more resource-efficient strategy but also promotes a broader, interconnected creative ecosystem that caters to the community needs of the wider area, thus fostering a more inclusive and expansive artistic and cultural milieu.

The city of Maribyrnong has been implementing creative program along the river, like residency programs at the Artsbox Artist in Residence Program, cultural festival at the Footscray park. A collaboration between the two council could expand the creative cluster spatially, enhancing creative dynamics across the riverside area.

Co working spaces have been identified as catalysts for innovation and collaboration. When artists from diverse backgrounds share a workspace, it not only leads to artistic collaborations but also fosters mutual understanding and respect. Shared workspaces will naturally foster interactions, discussions, and potential collaborations between Aboriginal artists and the broader artistic community (Landry, 2012).

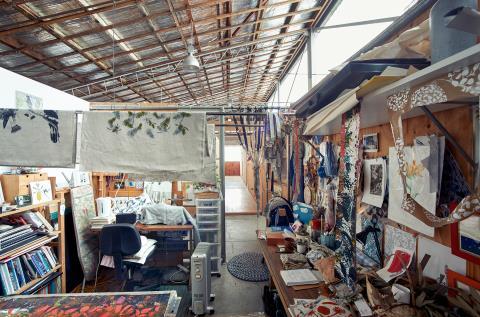

The existing industrial space within the site offer ample space to repurpose into collaborative workspaces. The River Studio , refurbished by a vacant warehouse are providing 57 artist studios, housing 75 artists, this illustrated the potential demand for more studios space. Moreover, Studio dividers were constructed using cyclone wire fencing and timber framing, and were intricately designed with donated, discovered, and salvaged materials . A significant portion of this work was undertaken in collaboration with artists and students, leading to unconventional solutions (Heritage council of Victoria, n,d) This examined the potential of shared studio in foster artistic innovation.

Strategy

State level

Plan Melbourne (20172050)

Creative State Strategies (2018-2028 )

National Indigenous Visual Arts Action Plan (20212025)

Collaboration/ Support

This strategy support the state policy by boosting the Creative Industries and Promoting Aboriginal Cultural Engagement.

Possible collaboration :

- Partnerships with state-funded cultural institutions to host marketplace and shared studio spaces

- Develop collaborative projects with Indigenous artists for artwork along the Heritage trail

Municipal Strategic Statement

Urban Renewal Initiatives

- Dynon Precinct

Local Strategies

Creativities Strategy

Creative Funding Framework

Arts Infrastructure Framework

Public Art Framework

Relevant councils

Councils involved in the Maribyrnong Waterfront River Valley Design Guidelines

City of Maribyrnong’s strategies

This strategy support the MSS by boosting supporting the economic development. Converting land use to creative spaces should consider alignment with the border Renewal plan.

This strategy support the overarching creative strategy

The framework provides a foundation to fund artistic and cultural projects for the Grant Program

The framework advocates for infrastructural developments that support the arts at the waterfront.

The framework offered established engagement with local artist to support the art installation plan

The action in this strategy should align with the guidelines to ensure consistency along the river

Goal 3 action 1 : Collaborate on art and cultural project eg. Public art , festival and joint art competition

Measuring the success of promoting Aboriginal Culture relies on a mixed-method approach. Qualitative metrics include visitor counts and installations volume indicating public and artist engagement. Partnerships with Aboriginal communities ensure authentic cultural representation. Public understanding is assessed through surveybased qualitative research.

Action Indicator

1. Cultural Heritage Trail

Number of visitors to the trail

2. Public art installation

3. Art Marketplaces

Data Collection Review Timeframe

Visitor log, Electronic counters

Number of partnerships with Aboriginal communities Partnership agreements

Number of public art installations completed Project records

Public engagement and understanding Public surveys

Number of marketplaces organized Event records

Number of participated artists and visitor Registration records

Amount of artwork sold, and revenue generated Sales records

Annually

Boost the creative industry by growing the creative cluster

Measuring a growing cluster adopt a quantitative approach mainly on the increase of creative spaces and artist in the site.

1. Streamline permitting process

2. Residency Program

3. Grant Program

Number of converted spaces

Number of residency space and resided artists

Number of new creative spaces with grant supported

Permit records review

Bi-annually

Registration records

Cultivate a collaborative environment that encourages artistic synergy and innovation

Measuring a collaborative environment also relies on a mixed-method approach. Qualitative metrics on number of projects, spaces and artists indicating the performance of the collaboration. However, Surveys, Interviews provide more in-dept insight to measure if the artists can benefit from the collaborative environment.

1: Collaborate with city of Maribyrnong on art and cultural project

2: Develop more shared studio spaces

Number of collaborative projects initiated

Number of artists and creative businesses engaged in collaborative projects

Number of shared studio spaces developed

Number of artists utilizing shared studio spaces

Number of collaborative projects initiated

Artists' satisfaction with collaborative opportunities

Project record

Bi-annually

Development records

Studio records

Surveys, Interviews

Quarterly

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2021). 2021 Census All persons QuickStats. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/productsbyCatalogue/FCC055588D3EBA19CA2584A8000E78 89?OpenDocument

Albrechts, L. (2006). Shifts in Strategic Spatial Planning? Some Evidence from Europe and Australia. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 38(6), 1149–1170. https://doi.org/10.1068/a37304

Beck, U. (2002). The Cosmopolitan Society and Its Enemies. Theory, Culture & Society, 19(1 –2), 17–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/026327640201900101

Chen, J., Judd, B., & Hawken, S. (2016). Adaptive reuse of industrial heritage for cultural purposes in Beijing, Shanghai and Chongqing. Structural Survey, 34(4/5), 331–350. https://doi.org/10.1108/SS-11-2015-0052

Creative Victoria, C. (2022, November 16). National Arts Participation Survey (Victoria) [Text]. Creative Victoria. https://creative.vic.gov.au/resources/audience-participation-survey

Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries, Government of Western Australia. (2020). Public art. Department of Local Government, Sport and Cultural Industries. https://www.dlgsc.wa.gov.au/culture-and-the-arts/public-art

Domain Group. (2023). Domain Rental Report June 2023. Domain. https://www.domain.com.au/research/rental-report/september-2023/

Gantait, A., & Sinha, R. (2019). Heritage Tourism Being a Tool to Rejuvenate Indigenous Culture: Select Case Studies on Indian Context.

Geia, L. K., Hayes, B., & Usher, K. (2013). Yarning/Aboriginal storytelling: Towards an understanding of an Indigenous perspective and its implications for research practice. Contemporary Nurse, 46(1), 13 –17. https://doi.org/10.5172/conu.2013.46.1.13

Girard, L. F., Kourtit, K., & Nijkamp, P. (2014). Waterfront Areas as Hotspots of Sustainable and Creative Development of Cities. Sustainability, 6(7), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/su6074580

Hall, S. (1994). □ Cultural Identity and Diaspora. In Colonial Discourse and Post-Colonial Theory. Routledge.

Inkifi. 2020. The World's Most Creative Cities. [online] Available at: <https://inkifi.com/most-creativecities/> [Accessed 17 November 2020].

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, B. (1998). Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage. University of California Press.

Kornberger, M. (2012). Governing the City: From Planning to Urban Strategy. Theory, Culture & Society, 29(2), 84–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276411426158

Kostopoulou, S. (2013). On the Revitalized Waterfront: Creative Milieu for Creative Tourism. Sustainability, 5(11), Article 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5114578

Landry, C. (2012). The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators. Earthscan.

Landry, C. (2012). The Creative City: A Toolkit for Urban Innovators. Earthscan.

Le Roux, G. (2014). Australian Indigenous ‘artists’ critical agency and the values of the art market. Les Actes de Colloques Du Musée Du Quai Branly Jacques Chirac, 4, Article 4. https://doi.org/10.4000/actesbranly.549

Lee, M. (1997). Cultural Methodologies. In Cultural Methodologies (pp. 126–141). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446250396

Mommaas, H. (2004). Cultural Clusters and the Post-industrial City: Towards the Remapping of Urban Cultural Policy. Urban Studies, 41(3), 507–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098042000178663

Morphy, H. (1999). Encoding the Dreaming–A theoretical framework for the analysis of representational processes in Australian Aboriginal art. Australian Archaeology, 49(1), 13-22.

Nishimura, E., Shambroom, H., & Silva, S. (2017). Navigating the Creative Processes for the Arts and the Third Cultural Space: A Comparative Analysis of Two International Artist Residency Programs. The International Journal of Social, Political and Community Agendas in the Arts, 12(2), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.18848/23269960/CGP/v12i02/37-57

Oakley, K. (2006). Include Us Out Economic Development and Social Policy in the Creative Industries. Cultural Trends, 15(4), 255–273. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548960600922335

Phelps, N. A., & Nichols, D. (2022). Can Growth Be Planned? The Case of Melbourne’s Urban Periphery. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0739456X221121248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X221121248

Pratt, A. (2009). Urban Regeneration: From the Arts `Feel Good’ Factor to the Cultural Economy: A Case Study of Hoxton, London. Urban Studies, 46, 1041–1061. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009103854

Productivity Commission, corporateName:Productivity. (2021, August 5). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visual arts and crafts Commissioned study. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/indigenous-arts

Sanders, E., & Stappers, P. J. (2008). Co-creation and the New Landscapes of Design. CoDesign, 4, 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880701875068

Scheyvens, R., Carr, A., Movono, A., Hughes, E., Higgins-Desbiolles, F., & Mika, J. P. (2021). Indigenous tourism and the sustainable development goals. Annals of Tourism Research, 90, 103260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2021.103260