New Source & Summit Missal Seeks to Help Raise Up and Renew Liturgy

By Joseph O’Brien

National Catholic Register—Over the last decade, the Church has struggled to draw people closer to the celebration of the liturgy—and especially the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. Lack of attendance at Mass among younger Catholics, a lack of belief in the Real Presence, and congregations minimized by CO VID-19 (and the resulting strictures on public gatherings) have all been contributing factors in this struggle.

But Adam Bartlett, CEO and founder of the liturgical publisher and tech company Source & Sum mit, hopes to provide the resources necessary to help renew and refocus the beauty and simplicity of the liturgy at Catholic parishes, campus ministries, and other faith com munities in the Church. And, as Bartlett sees it, Source & Summit couldn’t have come at a better time to help the Church meet the chal lenges it faces in fostering transcen dent and transformative encounters with Christ in the liturgy that help form and equip disciples for the Church’s mission.

Pope Francis, in his recent ap ostolic letter on the liturgy, Desid erio Desideravi, acknowledged that there are those who know about the Church’s invitation to participate in the liturgy but “have forgotten it or have got lost along the way in the twists and turns of human living.” The Pope’s words seem especially true in the U.S.; for, while Pope Francis does not offer specifics

Adoremus Bulletin

For the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy

To Adore the Father in Spirit and in Truth: The Liturgical Vision of Benedictine Mother Cécile Bruyère

By Kevin D. Magas

Feminist theologian Marjorie Procter-Smith criticized the classical 20th-century liturgical movement as being exclusively initi ated and led by men in general and priests in particular, in contrast to the women’s movement as started and directed by women.1 However, women such as Dorothy Day, Therese Muel ler, Mary Perkins Ryan, Justine Ward, and many others offered distinctive and substantial contributions to the liturgical movement. Although recent scholarship has sought to give greater visibility to women’s integral contribu tions to the movement,2 this renewed attention doesn’t often extend to the movement’s roots in 19th-century France.

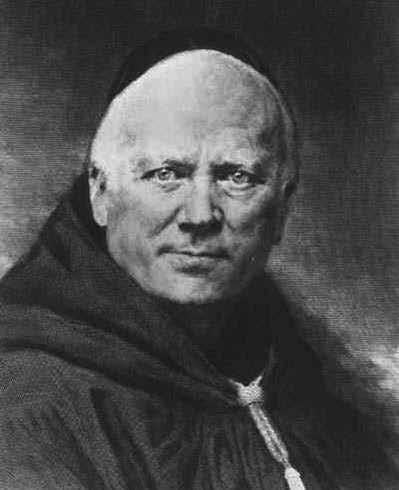

Students of the movement will recog nize the pivotal role that Dom Prosper Guéranger, the “father of the liturgical movement,” played. Besides restoring Benedictine life at the monastery at Solesmes after the French Revolution, this great Benedictine contributed to the revival of Gregorian chant, histori cal scholarship on the origins of the liturgy, and renewed appreciation to liturgical time in his popular commen taries on the liturgical year. Less well known is another Benedictine, Mother Cécile Bruyère (1845-1909), the founding abbess of St. Cecilia, the first women’s monastic foundation of the Solesmes congregation. Although her contributions are often overlooked in most historical accounts of the liturgi cal movement, she not only anticipated many of the theological emphases of the 20th-century movement and the Second Vatican Council, but she also articulated a distinctively contempla tive and liturgical spirituality worthy of revisiting today.

Early Life

Mother Cécile was born Jeanne-Hen riette “Jenny” Bruyère to a well-to-do French bourgeoise family in Sablé-surSarthe in western France. While her father was an irate man who despised religion and never attended Mass, her mother was a devout Catholic from whom she received much of her reli gious education and formation in the meaning of the liturgical feasts. In her autobiographical memoirs, which are strikingly similar in tone and content to St. Thérèse of Lisieux’s Story of a

Soul, she displayed an intuitive aware ness of God’s presence at an early age: “I was beginning to think, to talk, and I already had a precise notion (my Lord) of Your presence everywhere. When I was taken to church, although the hour was quite early, I would be very still and quiet, in great tranquil ity, for as long as we remained there.”3 Nevertheless, Bruyère did not have a docile character, but was often de scribed as proud, stubborn, and prone to bouts of anger and scrupulosity. The course of her life changed when she came into contact as a young girl with Dom Prosper Guéranger. Her mother’s family owned a country house by the sea that they visited near Solesmes, and Guéranger’s influence spread over the family as he converted and mar ried many of its members and became pastorally involved in their lives.

When Bruyère came down with a fever and was unable to make her First Communion, her aunt asked Guéranger to personally prepare her, thus beginning a relationship of spiritual direction and spiritual friendship that would continue for the rest of their lives. Upon Bruyère’s First Communion, Guéranger gave her a piece of cloth from the tomb of St. Cecilia, resonating with her secret desire of preserving and consecrating

her virginity to God. Bruyère’s account of Guéranger as a spiritual father is very moving and reveals a tenderness and spiritual depth of a figure that was often perceived as polemical and “warlike” (a play in French on his last name, “Guerre-anger”). In addition to her spiritual formation, Guéranger taught her Latin, which was not typically a part of the classical curriculum of women at the time, simply because she expressed a desire to understand and take an active part in the prayers of the Church.

Foundation of Saint-Cécile

In the context of Guéranger’s spiri tual direction, Bruyère grew in a deeper desire for a contemplative life shaped by the Benedictine liturgical spirituality Guéranger had revived in the restoration of the monastery of Solesmes (rather than the traditional path towards Carmelite spirituality for aspiring nuns in France at that time). Although Guéranger never intended to initiate a women’s founda tion to Solesmes, he perceived Bru yère’s spiritual charism of leadership among a group of lay women involved in apostolic work called “The Great Catechism.” In 1866, these women gradually formed a sort of pre-no vitiate under Guéranger’s direction, and, at the young age of 22, Jenny was entrusted as the superior of the new foundation. Guéranger formed them in a liturgical spirituality that was largely absent in women’s cloistered spiritual ity at the time: how to pronounce the Latin well, sing Gregorian chant, and understand the rubrics of the Mass. As he instructed them on how to live from the Divine Office, the feasts of the liturgical year and the saints, and the Rule of Benedict, he also worked at raising funds to further develop the fledgling foundation on a more perma nent structure on a hill a few minutes’ walk from Solesmes.

In beginning the women’s founda tion, Guéranger anticipated future ecclesial and liturgical developments. While the post-Tridentine practice largely consisted of bishops assum ing direct responsibilities for religious communities of nuns, these bishops often didn’t understand or fully appre ciate their congregation’s spirituality. In light of this, Guéranger advocated for the creation or a co-jurisdiction shared with the

the

of

A Women’s Movement (Too!)

The Liturgical Movement may have been started by men, but, as Kevin Magas demonstrates, women such as 19th-century Benedictine Sister Cécile Bruyère also played a vital role 1 Ratzinger and Romans

What’s Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI’s favorite scripture passage? Perhaps it’s Romans 12:1. Mariusz Biliniewicz explains how its message on sacrifice is a key to Ratzinger’s own 6 Liturgical Entrance Ramp

Four hundred years ago, St. Francis de Sales wrote Introduction to the Devout Life, and, as

Anne Koerner Simpson notes, it could just as well be called “Introduction to the Liturgical Life” 8

Upon Further Review…

The Mass is all that. English convert and Catholic apologist Ronald Knox in his book

The Mass in Slow Motion, reviewed by Joseph Tuttle, takes us through the motions that make it so 12

News

Views

continued on page 2

&

Story

Please see BRUYERE on page 4

Adoremus Bulletin NOVEMBER 2022 AB

News & Views 1

3 The Rite Questions 11 NOVEMBER 2022 XXVIII, No. 3 Adoremus PO Box 385 La Crosse, WI 54602-0385 NonProfit Organization U.S. Postage PAID Madelia, MN Permit No. 4

Editorial

bishop in order to bring

nuns back under the influence

the

Although Guéranger never intended to initiate a women’s foundation to Solesmes, he percieved Benedictine Sister Cécile Bruyère's spiritual charism of leadership among a group of lay women involved in apostolic work called “The Great Catechism.” In 1866, these women gradually formed a sort of pre-novitiate under Guéranger’s direction, and, at the young age of 22, Jenny was entrusted as the superior of the new foundation.

AB/WIKIPEDIA

VIEWS

Continued from NEWS & VIEWS about those who “have forgotten” the liturgy, accord ing to a 2016 Center for Applied Research in the Apos tolate report, 86% of baptized and confirmed Catho lics of the millennial generation in the U.S. no longer regularly practice their faith. In addition, even those who are practicing their faith may not even know what they’re practicing, as a 2019 Pew report indicates that 70% of Massgoing Catholics in the U.S. do not believe in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. To compound the dismal state of belief these statistics reveal, bishops and pastors are still looking for ways to return their flocks to the pews after COVID depleted churches in 2020.

This past summer, on the Solemnity of Corpus Christi, the U.S. bishops offered a formal response to these challenges when they announced a three-year Eucharistic Revival. But hand-in-hand with an effort to revitalize belief in the Eucharist through evangeliza tion and catechesis, Bartlett said, bishops, pastors, and the faithful also have an opportunity to “help revive Eucharistic faith by elevating the beauty and rever ence of our celebrations of the liturgy, and especially through sacred music.” And that’s where Source & Summit comes in.

According to Bartlett, Source & Summit “is aimed at helping make authentic liturgical renewal as acces sible as possible to ordinary parishes, in a way that helps inspire and invigorate missionary disciples to undertake the work of the New Evangelization.”

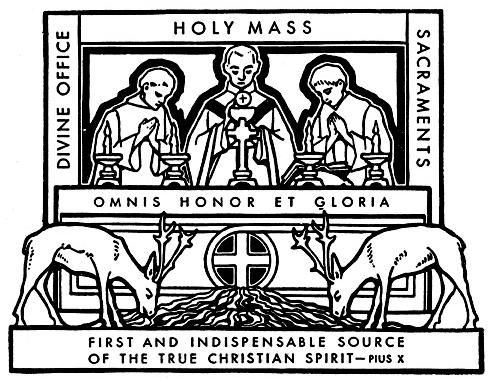

The name of the organization itself—Source & Summit—speaks directly to this connection between worship and the Church’s mission in the world, Bartlett said. The constitution on the liturgy of the Second Vatican Council, Sacrosanctum Concilium, Article 10, states that “the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the font from which all her power flows.”

“Our mission, ultimately, is to help parishes realize that ideal,” Bartlett said, adding, “With this image, the Church tells us that the liturgy is set upon the moun taintop of the Church’s life, above all the other impor tant and necessary things we do [such as catechesis, evangelization, and charitable outreach], but it’s distinct from these, and serves as the font and goal of them all.”

Source & Summit offers two primary resources to help parishes in their work of authentic liturgical renewal, Bartlett told the Register.

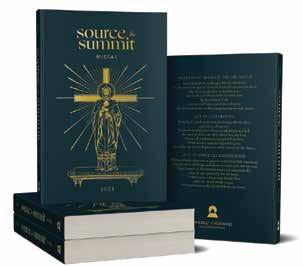

“First, through the Source & Summit Missal,” he said, “and, secondly, throughout the Source & Summit ‘Digital Platform’ for liturgy and music preparation. Both resources are designed to be used together, but they also can be used independently, based upon the needs of the parish.

According to Bartlett, the Source & Summit Missal, first published in 2021, is the flagship of Source & Summit’s offerings.

“When you first hold the missal,” he said, “you im mediately realize it was designed for something sacred and important. The custom cover art, whether it’s St. Gabriel the Archangel or Christ the High Priest, is set in gold leaf that radiates from the front cover, immedi ately drawing its viewers into the beauty of the liturgy.”

Describing the missal’s contents, Bartlett said that “while it offers parishes much of what they would expect to find in a pew missal or hymnal, such as the Lectionary readings and Order of Mass, what sets the Source & Summit Missal apart is its presentation of all of the texts that the Church invites us to sing in the Mass, paired with simple, beautiful melodies. This includes the Entrance, Offertory, and Communion Antiphons, each of which can be sung in simple, con gregation-friendly settings or to one of eight simple tones. This is in addition to the Responsorial Psalm and Alleluia, as well as the various special chants that occur throughout the year.”

Recalling the September 2020 directives on evalu ating Catholic hymnody issued by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Committee on Doctrine, Bartlett said that the Source & Summit Missal also “contains over 400 hymns in English, Latin, and Spanish that come from the core repertoire of time-tested, theologi cally sound hymnody for both liturgical and devo tional use.”

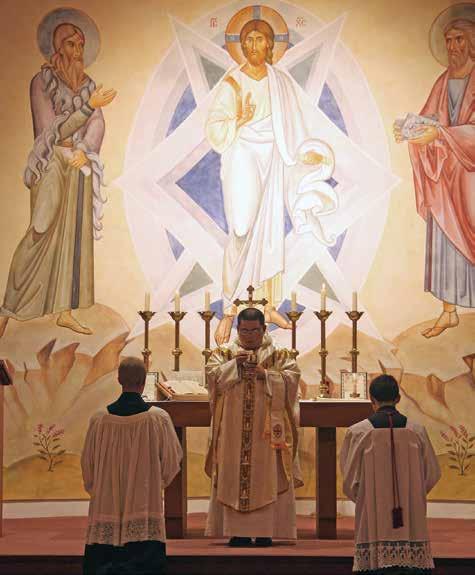

Msgr. John Cihak, pastor of Christ the King Parish in Milwaukie, OR, started subscribing to the Source & Summit Digital Platform during its pilot phase in 2020 and then added the Source & Summit Missal in 2021. Because his parish has more than 1,300 families and a grammar school to keep him busy, he has found Source & Summit to be a convenient and time-saving resource.

“Source & Summit has helped me because their

missal and digital platform are eminently practical,” he said. “As a pastor, I don’t have the time to find the content necessary for a beautiful liturgy, and I found that Source & Summit has already done that work for us. My sacred music director got familiar with these resources and started incorporating them gradually into the liturgy.”

Before coming to Christ the King, from 2009 to 2018, Msgr. Cihak served as an official for the Con gregation of Bishops and papal master of ceremonies in the Vatican. His four years of service under Pope Benedict XVI and five years with Pope Francis have helped him grow in his understanding of the Church’s view of the liturgy. It is an understanding he was keen to share with his parishioners at Christ the King.

“We strive at Christ the King to celebrate the sa cred liturgy as asked for by Vatican II,” he said.

For more information about Source & Summit and its resources, or to request a free review copy, visit SourceandSummit.com or call (888) 462-7780.

Benedict XVI Reflects on Vatican II in New Letter

By AC Wimmer, Shannon Mullen

CNA—In a new letter, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI characterizes the Second Vatican Coun cil as “not only meaningful, but necessary.”

Released October 20, the letter is addressed to Franciscan Father Dave Pivonka, president of Fran ciscan University of Steubenville in Steubenville, OH, which concluded a two-day conference on October 21, centered on the theology of Benedict XVI/Joseph Ratzinger.

Nearly three-and-a-half typewritten pages long, the letter provides fresh observations about Vatican II from one of the few remaining theologians in the Catholic Church to have personally participated in the historic council, which opened 60 years ago last October.

“When I began to study theology in January 1946, no one thought of an Ecumenical Council,” the 95-year-old retired pope recalls in the letter.

AB/L’OSSERVATORE ROMANO

radicality,” he continues.

“The same is true for the relationship between faith and the world of mere reason. Both topics had not been foreseen in this way before. This explains why Vatican II at first threatened to unsettle and shake the Church more than to give her a new clarity for her mission,” Pope Benedict writes.

“In the meantime, the need to reformulate the question of the nature and mission of the Church has gradually become apparent,” he adds. “In this way, the positive power of the Council is also slowly emerging.”

Ecclesiology—the theological study of the nature and structure of the Church—had evolved after World War I, Pope Benedict writes. “If ecclesiology had hith erto been treated essentially in institutional terms,” he says, “the wider spiritual dimension of the concept of the Church was now joyfully perceived.”

At the same time, he writes, the concept of the Church as the mystical body of Christ was being criti cally reconsidered.

It was in this situation, he says, that he wrote his doctoral dissertation on the topic of “People and House of God in Augustine’s Doctrine of the Church.” He writes that “the complete spiritualization of the concept of the Church, for its part, misses the realism of faith and its institutions in the world,” adding that “in Vatican II, the question of the Church in the world finally became the real central problem.”

Pope Francis: St. Pius V Teaches Us to Seek Truth, Pray the Rosary

By Hannah Brockhaus

CNA—Pope Francis on September 17 recalled the legacy of the 16th-century pope St. Pius V, a Church reformer who standardized the Mass and opposed heresy.

The teachings of Pius V “invite us to be seekers of the truth,” Pope Francis said in the Vatican’s Paul VI Hall to Catholics from northern and central Italy.

“Jesus is the Truth, in a sense that is not only uni versal but also communal and personal,” he said, “and the challenge is to live the search for truth in the daily life of the Church today, of Christian communities.”

The search for truth, Pope Francis said, “can only take place through personal and community discern ment, starting from the Word of God.”

He explained that the Word of God comes alive in a particular way in the Mass, in both the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist, “where we somehow touch the flesh of Christ.”

St. Pius V, he said, reformed the liturgy of the Church, which was then further reformed four centu ries later at the Second Vatican Council.

“In these years much has been said about the Liturgy, especially its external forms. But the greatest commitment must be placed so that the Eucharistic celebration actually becomes the source of community life,” Pope Francis said.

He also recalled St. Pius V’s commitment to rec ommending prayer, especially the rosary.

St. Pius V was born Antonio Ghislieri in Bosco Marengo, Piedmont. The year 2022 marks the 450th anniversary of his death on May 1, 1572. His papacy began in 1566.

“When Pope John XXIII announced it, to every one’s surprise, there were many doubts as to whether it would be meaningful, indeed whether it would be possible at all, to organize the insights and questions into the whole of a conciliar statement and thus to give the Church a direction for its further journey,” Pope Benedict observes.

“In reality, a new council proved to be not only meaningful, but necessary. For the first time, the ques tion of a theology of religions had shown itself in its

Adoremus Bulletin

Society for the Renewal of the Sacred Liturgy

PHONE: 608.521.0385 WEBSITE: www.adoremus.org

MEMBERSHIP REQUESTS & CHANGE OF ADDRESS: info@adoremus.org

Pius V “faced many pastoral and governance chal lenges in just six years of his pontificate,” Pope Francis said. “He was a reformer of the Church who made courageous choices. Since then, the style of Church government has changed, and it would be an anachro nistic mistake to evaluate certain works of Saint Pius V with today’s mentality.”

“So too, we must be careful,” he added, “not to re duce him to a nostalgic, stuffed memory, but to grasp his teaching and witness. With this insight, we can note that the backbone of his entire life was faith.”

EDITOR - PUBLISHER: Christopher Carstens

MANAGING EDITOR: Joseph O’Brien

CONTENT MANAGER: Jeremy Priest

GRAPHIC DESIGNER: Danelle Bjornson

OFFICE MANAGER: Elizabeth Gallagher

MARKETING AND FUNDRAISING: Eugene Diamond

SOCIAL MEDIA: Jesse Weiler

INQUIRIES TO THE EDITOR P.O. Box 385 La Crosse, WI 54602-0385 editor@adoremus.org

EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE

The Rev. Jerry Pokorsky = Helen Hull Hitchcock

The Rev. Joseph Fessio, SJ

Contents copyright © 2022 by ADOREMUS. All rights reserved.

2 NEWS &

Adoremus Bulletin, November 2022

AB/SOURCE AND SUMMIT

Please see NEWS & VIEWS page 7

Let the Liturgy Shine—Symbolically, of Course.

By Christopher Carstens, Editor

When Alexander the Great made his way through Palestine in the 4th century BC, he left behind key features of Hel lenistic culture. Chief among these was the Koine dialect of the Greek language, which became the language of the New Testament.

Consequently, not only a great many secular words today, but a large number of ecclesial words (such as “ecclesial”) are Greek in origin: episcopate and diaconate, baptism and eucharist, evan gelization and martyrdom. The word “liturgy” is also Greek (leitrougias), in dicating a work (ergon) that is done on behalf of the people (laos), as is a term for one of the liturgy’s most essential concepts: symbol.

“Symbol” is built on the root ballein, which means to throw, hurl, or toss. Ballein is the root of today’s English word “ballistics.”

A “parable” is similarly structured on this root ballein, and it means “to throw (ballein) alongside (para),” as when Jesus tells a story that illustrates— but does not come out explicitly and state—a truth of faith. The “Parable of the Sower,” for example, speaks of the various types of soil (that is, souls) that receive the Word of God. Only after the parable has been told do the disciples ask him its core meaning (see Luke 8:115).

“Hyperbole” indicates an exaggerated way of speaking: “The Adoremus Bul letin is the best liturgical journal ever!” Literally, hyperbole means “to throw (ballein) up (hyper).”

An “embolism” is an obstruction that has been “thrown (ballein) into (em)” the heart or artery. Less painfully—in fact, more helpfully—the priest “throws in” a special prayer or elaboration after the Lord’s Prayer and before its conclu sion at Mass, when he says, “Deliver us, Lord, we pray, from every evil, graciously grant peace in our days…”— thus, this heart-felt prayer is also called an embolism.

Even evil throws its weight around. “The devil (dia-bolos) is the one who ‘throws himself across’ God’s plan and his work of salvation accomplished in Christ” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2851).

But let’s now throw ourselves back together with the term “symbol.” The liturgy, the Catechism teaches, “is woven together from signs and sym bols” (1145). Every ritual is a tapestry of symbols—objects, actions, words, ministers and people, times, music, art, and architecture. Think, for example, of the Introductory Rites of the Mass, or the baptism of an infant, or the celebra tion of Vespers. In each and every case, the ordered use of symbols “throw together.” But throw together exactly what?

In the beginning, when God made the cosmos (which is an another Greek term, meaning order and beauty), heaven was united to earth, God walked together with man, and all lived togeth er in unity and peace. But with sin—en ter the diabolic one—cosmos turned to chaos: creation separated from heaven, man hid himself from God, and the fallen world came to disorder. What was needed to undo the separation and restore unity was a great Symbolizer— indeed, a super-symbolizer: a sacramen talizer—who could throw heaven and earth, God and man, and all of creation together again. This is the incarnate Christ.

His work of rejoining heaven and

earth, however perfect, is as of yet incomplete. In God’s grand plan, we are called to join him in joining earth to heaven once again. And the greatest means by which this saving and sanc tifying work is accomplished is in the liturgy and sacraments. Woven “from signs and symbols,” liturgical celebra tions restore us to God.

Much rides, then, on getting sacra mental signs and symbols right. And by getting them right, I mean both representing fully and clearly the divine realities they signify, and also allowing us fallen beings to engage them and reunite ourselves through them, and Christ, to God. Most liturgical debates can be reduced to this basic level: do the various ritual symbols—words, music, gestures—bring together heaven and earth? Or, perhaps, are they “lop sided” (not a Greek word, by the way), by not revealing the mystery as fully and authentically as they might, or, for a variety of reasons, by thwarting our encounter with the mystery?

The seriousness of liturgical symbol ism was a large part of what Sacrosanc tum Concilium addressed in its reforms. Pope John XXIII first laid some found ing principles when he opened the Council on October 11, 1962: “The sub stance of the ancient doctrine of the de posit of faith is one thing, and the way in which it is presented is another” (em phasis added). In liturgical terms, the divine reality of the liturgy—the saving work of Christ—remains an unchang ing reality for all ages, yet the manner in which it is symbolized requires that it be adapted, when possible, to the condi tions of those who celebrate.

Sacrosanctum Concilium would say as much when it established norms for the reform and restoration of the liturgy’s sacramental signs: “That sound tradition may be retained, and yet the way remain open to legitimate prog ress…” (22). And again: liturgical signs and rites “are to be simplified, due care being taken to preserve their substance” (50). Yet, even while liturgical signs and symbols “preserve their substance,” they should radiate with “a noble simplicity; they should be short, clear, and unen cumbered by useless repetitions; they should be within the people’s powers of comprehension, and normally should not require much explanation” (34). To rejoin heaven and earth—to symbol ize—sacramental symbols must be both heavenly and earthly.

Prior to the Council, a common complaint about liturgical symbol ism claimed that its expression of the mystery was “overlaid with whitewash” (Benedict XVI, The Spirit of the Liturgy, preface) and that it needed to be “puri fied of the imperfections brought by time, newly resplendent with dignity and fitting order” (Pius X, Motu proprio Abhinc Duos Annos, 1913). Postconcil iar reforms certainly “laid bare” (Pope Benedict XVI) the essentials, but in so doing stripped away much that was meaningful, leaving a symbol system too didactic and lacking beauty.

So we still work today to understand, celebrate, and appreciate the liturgy’s symbols. Far from obscure, yet never anemic, liturgical symbolism ought to radiate the glory of God to eyes and ears willing and able to see and hear. When we can hit upon such a formula, we are truly reunited to God.

The Blessed Virgin Mary, follow ing the remarkable events of her Son’s conception and birth, “kept all these things, reflecting on them in her heart” (Luke 2:19). Writing in Greek, Luke the Evangelist said more than “reflecting,”

Far from obscure, yet never anemic, liturgical symbolism ought to radiate the glory of God to eyes and ears willing and able to see and hear. When we can hit upon such a formula, we are truly reunited to God.

but, rather, “symbolizing” (symballousa) these things in her heart, fitting them together into a whole that kept her in

union with God’s plan. May she pray for us now as we pray for citizenship in the Heavenly Jerusalem.

Now Available!

Romano Guardini’s Liturgy and Liturgical Formation

Available in English for the first time!

KEVIN

In Liturgy and Liturgical Formation, Guardini presents the specific task of the liturgy, and by extension, the ways in which the liturgy forms us to respond to sacramental signs and to understand our place in the community. Pope Francis drew upon Guardini’s insights from Liturgy and Liturgical Formation in his recent apostolic letter, Desiderio Desideravi, highlighting how, as Guardini wrote, the liturgy forms us “to relate religiously as fully human beings.” The ongoing formation and education of the assembly is essential, and this work provides a lens through which this formation can be realized.

Paperback, 6 x 9, 160 pages 978-1-61671-677-6 | Order code: LLF $22

Order today at LTP.org or your local bookstore

3 Adoremus Bulletin, November 2022

“In this long-awaited English translation of Liturgy and Liturgical Formation Guardini prompts us to consider more profound questions about the nature of the liturgy than the superficial discussions which often permeate the Catholic blogosphere. Here is a timely reminder that we need to be formed to participate in the liturgy in order for it to transform our daily life in the world.”

D. MAGAS, phd Assistant Professor of Dogmatic Theology Director of Intellectual Formation, The Liturgical Institute University

of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary

www.LTP.org | 800-933-1800 A23LLF

AB/LAWRENCE OP ON FLICKR

Continued from BRUYERE, page 1

Benedictine monks who could better help cultivate their spiritual charism. In practice, Guéranger did not think of himself as the “superior” of the nuns but fully entrusted the power and governance of the women’s foundation to Bruyère, believing this better reflected the ancient office and role of the Abbess. Guéranger also set a liturgical precedent by reviving an ancient tradition during the nun’s ceremony of profession. Guéranger combined the rite of monastic profes sion with the rite of the consecration of virgins as it was described in the Roman pontifical, even though this rite had fallen into practical disuse by the 15th century. In reviving the rite of the consecration of virgins, the Abbey of St. Cécile started a precedent among monastic orders that spread and was later recommended by Pius XII’s apostolic constitution Sponsa Christi as “one of the most beautiful monu ments of the ancient liturgy.”4

from the spiritual influence she had, not only over her own nuns, but over the monks of Solesmes as well, who streamed to her for spiritual guidance. The abbot approved of this, and the novitiate at Solesmes almost took place at the feet of Bruyère, whom the monks came to in order to encounter the thought and spirit of the departed Guéranger.6 However, two monks resented her spiritual authority, and blamed her for interfering in the election of their new abbot. They claimed she was trying to bring back to life the monasticism of the medieval abbey of Fontevrault, in which the abbess was the head of the order, having the monks as well under her jurisdiction. However, they took this all the way to the Pope Leo XIII, who enforced harsh separations between the monasteries until they could sort out the situation. Even after a visitation found the accusations baseless, the mod ernist Albert Houtin published a calumnious account accusing Bruyère of “moral hysteria.” It should be

come to know profoundly the liturgical prayers and all that makes up the public prayer of the Church, and no one will be able to remonstrate with you in matters of doctrine…. With this, one can form priests and saints, and I reckon that if this were the basis of education in theological schools, it would bring about the development of souls. Poetry, music, and the arts would play their part, as much as the intelligence and heart, and instead of producing either ‘nullities’ or ‘specialists’ we would see the emergence of ‘men,’ that is, intelligent creatures, complete and able.”8 To another, she gives a similar exhortation: “My dear little brother, run well after the fragrance of the per fumes that our great King has left behind Him in His church, by which I mean, always profit by the Holy Scriptures and the sacred liturgy.”9

Bruyère also advocated for a spiritual nourishment on the primary sources of scripture and the liturgy in her conferences with her nuns, several of which were transcribed. Many of her conferences were given directly on Scripture, and she worked through the Old Testament book by book. Unlike other religious of her time, she ensured her nuns had not only a psalter and New Testament but an entire Bible. Re gretting that Catholics viewed scripture as a remote “museum-piece” or as part of an apologetic arsenal against Protestants, she instead revived the ancient monastic practice of lectio divina, a meditative, prayerful “chewing” on the Word of God which sees the Word as a profound source of spiritual nourish ment. Bruyère’s nuns were even accused by certain

Abbess and Mother of Souls

Bruyère received the abbatial blessing and enthrone ment in 1871, four years before the death of Abbot Guéranger in 1875. Her biographer, Dom Guy Oury, notes that Guéranger’s guidance and spiritual direc tion, ultimately culminating in encouraging her to lead on her own, helped form this once stubborn but gifted girl into a true mother of souls, a fact over whelmingly noted by both the nuns and monks of Solesmes. Her character traits bear a resemblance to Teresa of Avila: she had a dynamism, liveliness, humor, simplicity, and attentiveness to details. She gave pride of place to the Office and joyful recreation, always reminding the nuns of the essentials in the spiritual life: “If you are in need of a good word, open your breviary, your Old Testament, your psalms; therein is our spiritual direction, and it is guaranteed by the Holy Spirit; we do not have need, as elsewhere, of so many spiritual directors.”5 Under the direc tion of Bruyère, the abbey grew in influence and was viewed as a model of Benedictine life, leading to the establishment of two other foundations in her lifetime.

Although Bruyère’s description of her interior life as Abbess bears witness to her growth in the unitive way of contemplative prayer, her life in the world was marked by many challenges. The first challenge was with a new bishop who didn’t like the indepen dence in governance that Guéranger had given her and wanted matters back under his control. Bruyère fought this, preparing a brief that shows the relevant historical tradition in favor of the way the monas tery was governed, and her appeal was ultimately upheld by the Pope Leo XIII. Another issue arose

noted that Houtin produced this account after he had left the priesthood and sought to settle scores with the hierarchical Church.

Near the end of her life, the volatile political situ ation in France led to the eviction of the contempla tive monastic orders which were viewed as lacking any utilitarian contribution to society. The nuns had to move to a foundation in England where Bruyère eventually died in exile in 1909. Weakened by the baseless attacks on her character, the uprooting of her monastic community, and failing health due to anemia, she spent the last six years of her life in a silent offering of herself to God in her cell. In all these events she did not fail to trust the workings of divine providence: “We are quite simply in the divine hands of him who has deigned to take seriously the offering of all our being which we so often renew. Isn’t it only just that among the members of our Lord Jesus Christ there be some who consent to be attached to the same cross as He, to die with Him, according to the will of the Heavenly Father and for the adorable purposes of His intentions?”7

Her

Teaching: Letters and Conferences

Bruyère’s spiritual and liturgical contributions are vis ible in the extensive correspondences she maintained through her letters, her conferences to her nuns, and her influential, widely circulated book on prayer, The Spiritual Life and Prayer According to Holy Scripture and Monastic Tradition. Her letters were a central part of her ministry of spiritual motherhood, and many of the letters she sent to monks were kept and treasured by them their entire lives. These often in cluded encouragements to root one’s spiritual life and monastic vocation in the liturgical life of the Church. In a letter to a young monk she extols the formative capacity of the liturgy: “Oh! Mark well, my brother,

critics as “not praying” simply because they did not practice the discursive, methodic type of mental prayer which had grown in popularity in the 16th and 17th centuries, even though their own lectio reflected a more ancient and universal monastic practice.10 As Bruyère often reminded her sisters, “If the Holy Spirit doesn’t feed your soul himself, you must look for food by reading the Holy Scriptures.”11

Her conferences thus advocated a return to the pri mary sources of sanctification: the celebration of the liturgy and sacraments, knowledge of the scriptures, and the doctrines of the Church. She lamented that Catholics of her era derived their spiritual nourish ment from innumerable devotions rather than a spiri tual encounter with Christ in the liturgy, a choice she compares to preferring to drink from a “bottle” rather than the ocean: “That is the reason for our existence, we who are daughters of St. Benedict. We must prefer this life of the Church to all possible and imagin able devotions. To live from the life of the Church; to observe above all what the Church enjoins us to do, to desire but one thing: to live this life to the fullest…. What would you say of someone who, being able to satiate himself in the ocean, prefers to drink from a bottle? He would say: ‘but this is water from the sea, it is enough for me.’ Well! I prefer the ocean. If you prefer the bottle, I leave it to you.”12

Bruyère challenged her sisters to remember the Rule of Benedict’s admonition to prefer nothing to the opus Dei, to God’s work in us and for us in the liturgical life of the Church. In an era suffused with the utilitarian understanding of the Enlightenment that the monk or nun needed to perform some sort of active work of charity or scholarship to contribute to society, Bruyère deepened Guéranger’s articula tion of the contemplative charism of Solesmes. In her conferences she insists on the primacy of the Divine Office, prayer, and the quest for God above all things

“Her conferences advocated a return to the primary sources of sanctification: the celebration of the liturgy and sacraments, knowledge of the scriptures, and the doctrines of the Church.”

AB/WIKIPEDIA

The course of Cécile Bruyère's life changed when she came into contact as a young girl with Dom Prosper Guéranger. Her mother’s family owned a country house by the sea that they visited near Solesmes, and Guéranger’s influence spread over the family as he converted and mar ried many of its members and became pastorally involved in their lives.

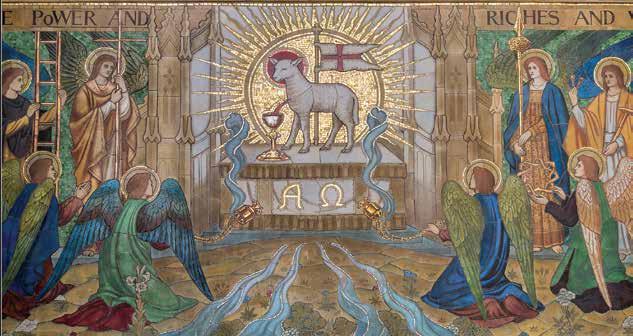

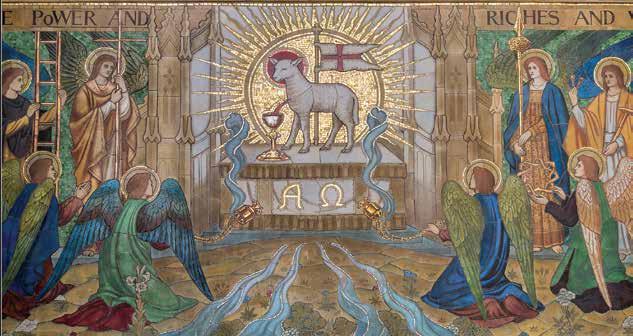

AB/PHIL MCIVER ON FLICKR. ADORATION OF THE LAMB AT THE CHURCH OF ST MARY MAGDALENE, NEWARK, UK.

In our own time, when many liturgical discussions fixate on external forms or rubrical details, Cécile Bruyère’s liturgical spirituality reminds us that the ultimate purpose of the liturgy is to fashion us into true adorers of the Lord in spirit and truth.

4 Adoremus Bulletin, November 2022

“Her character traits bear a resemblance to Teresa of Avila: she had a dynamism, liveliness, humor, simplicity, and attentiveness to details.”

and their apostolic fruitfulness for the salvation of the world. In many instances, her conferences echo Thérèse of Lisieux’s “little way,” highlighting the beauty of mundane, ordinary things done with extraordinary love for the glory of God: “Who can say how much merit and recompense God has reserved for us by our accomplishment of the most humble of our daily duties? We belittle these things too much. Who has organized our life as it is? Was it not the Creator Him self?...If the good God had wanted something else for us, he would have made us differently.”13

The Spiritual Life and Prayer

The main distillation of Bruyère’s teaching on the spiri tual life and its essential foundations in the Bible and the liturgy can be found in her work The Spiritual Life and Prayer According to Holy Scripture and Monastic Tradition. While Guéranger had advocated for the primacy of the Divine Office, liturgy, and lectio divina in private conferences to his monks, his thoughts on these subjects remained unpublished. Bruyère’s intent was to engage in a thoroughgoing ressourcement of the monastic tradition and write the book on prayer Guéranger would have written had he the required time and desire to do so.

The very structure of Bruyère’s work manifests a liturgical “frame” to the spiritual life. In this respect, Bruyère’s work differs in tone and emphases from standard scholastic spiritual theology textbooks writ ten around the time, such as Adolphe Tanquerey’s The Spiritual Life. While Bruyère includes a standard account of the purgative, illuminative, and unitive stages of classical treatises on the spiritual life, a con sideration of the sacraments and liturgy at both the beginning and end of the work serve as “book-ends” to remind the reader that they serve as both the “source” and the “summit” of the spiritual life.

One of the central themes pursued from the very be ginning of her text is what the Second Vatican Council later referred to as “the universal call to holiness,” a familiar theme in our contemporary theological con text but scarcer in spiritual literature of the late 19th century. “The secrets of the spiritual life,” she reminds us, “are not reserved exclusively for a few chosen souls, as people too often believe, nor for those only who make religion their specialty. All men are created by God; all are called to save their souls; all are regener ated by the same means…. ‘One Lord, one faith, one baptism.’”14 In fact, Bruyère grounds her entire account of the spiritual life as the unfolding and actualization of the graces received at baptism.15 For her, the heights of contemplation must not be relegated to extraordi nary visions or mystical raptures given to a select few but the progressive growth in the likeness of Christ available to all through communion in the sacramental life of the Church. The sacraments are the certain and authentic “means instituted by God for enabling man to attain to holiness, without there being any need to look for extraordinary means…. They communicate God to man and hence they all tend to divine union; they are provided with the energy necessary to bring it about, and they enable us fully to attain our end.”16 Rather than a doloristic spirituality of “suffering for suffering’s sake” popular in certain strains of Romantic spirituality of the time, Bruyère articulates a theol ogy of divinization and desire for happiness which prompts the human being to search for God and ceaselessly gaze upon him who imprints himself upon us in the depths of our soul.17

Bruyère also treats a number of themes that would receive further attention later in the 20th-century liturgical movement. In an age where the Divine Office was often viewed strictly as a burdensome external, canonical obligation to fulfill rather than an intimate encounter with Christ, Bruyère draws attention to the mutually enriching relationship between private, silent, mental prayer and liturgical prayer: “Thus, by a double current, which consists in praying mentally the better to celebrate the Divine Office, and seeking in the Divine Office the food of mental prayer, the soul gently, quietly, and almost without effort arrives at true contemplation.”18 While many in Bruyère’s time viewed the liturgy merely in its rubrical and canonical dimen sions as the external, official worship of the Church, she insists on the preeminent spiritual role the liturgy has in fashioning us into “true adorers” of the Lord “in spirit and truth” (cf. John 4:23-24). She challenges her readers to live a life permeated by the spirit of the liturgy such that our hearts and voices unite with the hymn of praise and love the Word Incarnate offered on earth to his eternal Father.19 In this way, the “heart becomes an altar where God alone dwells, and offers to his Father a sacrifice of adoration, of praise and of love.”20 For Bruyère, we are assimilated to the myster

ies of Christ’s life through the sacred liturgy, and these mysteries must be reproduced in the sanctuary of the human heart such that we can say, “It is no longer I who live but Christ who lives in me” (Galatians 2:20).21

One of the chief theological retrievals that contrib uted to an enriched understanding of the liturgical act in 20th-century liturgical theology was a renewed understanding of liturgy as an exercise of the priestly office of Christ. In a theologically rich last chapter of

her advocacy for liturgy as the center of the spiri tual life foreshadowed fundamental concerns of the 20th-century liturgical movement. Without agitating for the reform of rites or texts, Bruyère shared in the primary goal of the movement classically understood as “a movement towards the liturgy, a movement towards the Christ-life giving mysteries” in order to usher in the “renewal and intensification of Christian life through its primary and indispensable source, the sacred liturgy.”25 In our own time, when many liturgi cal discussions fixate on external forms or rubrical details, Bruyère’s liturgical spirituality reminds us that the ultimate purpose of the liturgy is to fashion us into true adorers of the Lord in spirit and truth. Then the liturgy becomes a true school of prayer and contem plation, for “in the sacred liturgy the Church’s children have all their mother’s learning: it is the most perfect way of prayer, the most traditional, the best ordered, the simplest, and the one that gives the strongest im pulse to the freedom of the Holy Spirit.”26

her text, entitled “There is But One Liturgy,” Bruyère meditates on the eschatological dimension of the heav enly liturgy described in the book of Revelation which is opened up for our participation through Christ’s priestly work. She marvels at how the Incarnation en ables rational creatures to share in Christ’s praise and adoration of the Father. In baptism we become liturgi cal apprentices to Christ, the premiere liturgist, and join in his saving work on behalf of the world: “Thus the sovereign pontificate is eternal, and it is exercised forever; not only in the adorable person of the Son of God, but in that priestly tribe of which He is the Head, ‘a chosen generation, a kingly priesthood,’ wherein all are priests, although in different degrees, and all are called to concelebrate with the supreme Pontiff.”22 The pilgrim Church on earth shares not only in praise and adoration but anticipates Christ’s sacrificial love in the redeemed city of God: “During the days of her pil grimage our Pontiff would not abandon His bride; and by a wonderful way, and with a wisdom all divine, He found the means of identifying the sacrifice of earth with that of heaven, since there is but one priesthood, that of Jesus Christ, but one sacrifice on earth and in heaven, but one victim, namely the Lamb conquer ing yet slain…. Thus the Church’s hierarchy on earth through the wonders produced by the Sacraments, presents to the ravished gaze of the heavenly citizens a faithful reproduction of that which takes place ‘within the veil, ad interiora velaminis.’”23

While originally intended as a private work for the edification of her spiritual daughters, the book was translated into German and English, achieving widespread praise and commendation among bishops, theologians, and monasteries across Europe. It was acclaimed as a “watershed book” for bringing Catho lics to a transformative return to the primary sources of the Bible and the Church Fathers for their prayer at a time when a proliferation of devotions preoccu pied the spiritual life.24 In this way, Bruyère’s return to the essential sources of sanctification anticipated the 20th-century movement known as resourrcement, and

Pioneer Woman

Mother Cécile Bruyère’s substantial influence on the Benedictine monasteries who would be promoters of the 20th-century liturgical movement and the wide influence of her book on prayer throughout Europe’s ecclesial circles leads her biographer, Dom Oury, to argue that there are few women from the turn of the 19th century whose teachings have had such repercus sions.27 Not only should Bruyère’s contributions find their rightful place in histories of pioneers of the litur gical movement, but her advice on living a life formed by the rhythms of liturgical life should resonate in the hearts of all who celebrate the liturgy faithfully today. “Our best formation is made,” Bruyère concludes, “when the part played by the liturgy is not limited to the actual celebration of the Divine Office but when our whole life is grounded upon it, when the content of our prayer, as well as the principles for the correc tion and sanctification of the soul, are drawn from it. In it will be found the surest commentary on scrip tures, which are the true bread of the spirit after the Eucharist, and the true orientation of our piety.”28

Kevin D. Magas holds an MTS and PhD in theology from the University of Notre Dame. He currently serves as an assistant professor of dogmatic theology and direc tor of intellectual formation for the Liturgical Institute at the University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary, Mundelein, IL, where he teaches sacramental theology and liturgical studies. He lives in Mundelein with his wife and children.

1. Marjorie Procter-Smith, In Her Own Rite: Constructing Feminist Litur gical Tradition (Nashville: Abingdon Press 1990), 18-35.

2. See Katharine Harmon There Were Also Many Women There: Lay Women in the Liturgical Movement in the United States, 1926-1959 (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2012).

3. Dom Guy Marie Oury, O.S.B. Light and Strength: Mother Cécile Bruyère, First Abbess of Sainte-Cécile of Solesmes trans. M. Cristina Borge (Hulbert, OK: Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey, 2012), 8. The biographical details that follow here are drawn predominately from Oury’s account.

4. Ibid., 135.

Please see BRUYERE on page 9

“In baptism we become liturgical apprentices to Christ, the premiere liturgist, and join in his saving work on behalf of the world.”

5 Adoremus Bulletin, November 2022

Without agitating for the reform of rites or texts, Cécile Bruyère shared in the primary goal of the movement classically understood as “a movement towards the liturgy, a movement towards the Christ-life giving mysteries” in order to usher in the “renewal and intensification of Christian life through its primary and indispensable source, the sacred liturgy.”

Why Romans 12:1 Is Ratzinger’s Key to the Spirit and Truth of Worship

By Mariusz Biliniewicz

Romans 12:1 must be one of Joseph Ratzinger’s/ Benedict XVI’s favorite biblical quotations. It appears in many of his major works on the liturgy, and it is often used in his treatment of the sac rificial nature of the Eucharist. In this passage St. Paul writes: “I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sac rifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiri tual worship” (Revised Standard Version). The idea of “spiritual worship” (Gr. λογικὴν λατρεία) is translated into the English language in various ways: the New International Version talks about “true and proper worship,” the Douay Rheims-American Edition about “reasonable service,” the American Standard Version about “spiritual service,” the Christian Standard Bible about “true worship,” the Phillips New Testament in Modern English about “intelligent worship,” the New American Standard Bible about “spiritual service of worship,” the New Catholic Bible about “a spiritual act of worship,” and the New English Translation about “reasonable service.”

In order to understand what this idea means for Ratzinger, we need to place it in the context of his general understanding of sacrifice in the Christian sense (St. Paul talks about “living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God”). In The Spirit of the Liturgy (SL), Ratzinger believes that the true meaning of the Christian sacrifice (i.e., the Mass) is “buried under the debris of endless misunderstandings” (SL, 27) and that this causes problems not only in the ecumenical dialogue with non-Catholic Christians, but also in the inner-Catholic theological and liturgical debate.

“I appeal to you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, to present your bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God, which is your spiritual worship.”

— Romans 12:1

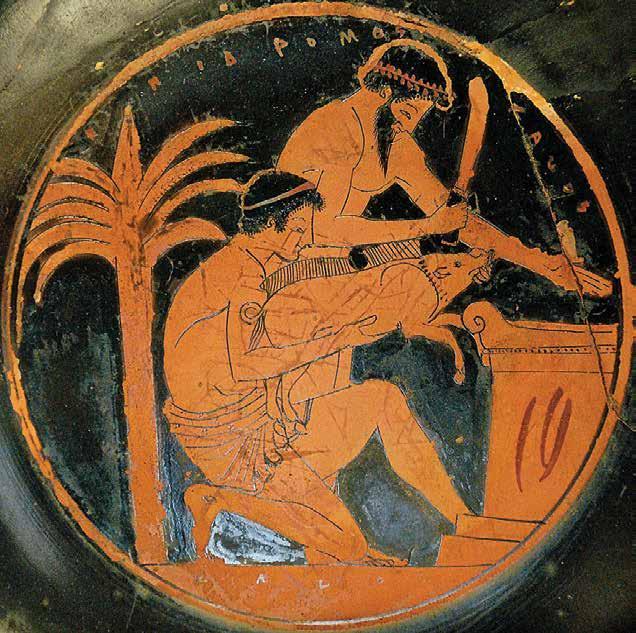

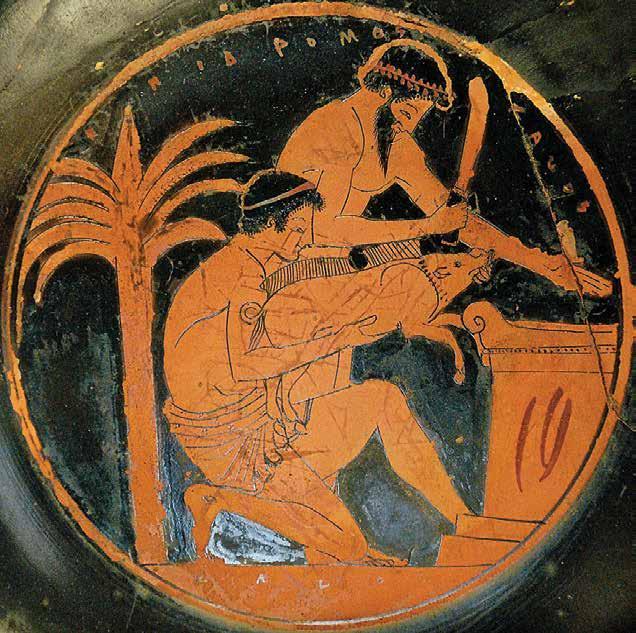

Sacrifice before Christ Ratzinger believes that “in all religions sacrifice is at the heart of worship” (SL, 27) and that the centrality of this concept in the history of religion is an expres sion of something important, a reality that concerns us as well (SL, 19). In pre-Christian religions, sacrifice was always associated with destruction and atone ment: man, aware of his guilt, wanted to offer to God (or gods) something that would bring him forgive ness and reconciliation. At the same time, these attempts of arriving at reconciliation with the deity were always accompanied by a sense of inadequacy and insufficiency: the offering could always be only a replacement of the true gift, which is the man himself. Animals or fruits of the harvest could not possibly satisfy God and could only serve as an imperfect rep resentation of the one who offers them.

The same could be said about the sacrificial system of the Old Testament. Bloody sacrifices of animals were to be offered by priests to God in order to recog nize his sovereignty and obtain his blessing. However, the Temple worship prescribed by the Law also “was always accompanied by a vivid sense of its insufficien cy” (SL, 39). The People of God slowly and gradually came to realize that there was nothing that they could offer God who owns everything. God wanted some thing else: “More precious than sacrifice is obedience, submission better than the fat of rams!” (1 Samuel 15:22); “I desire steadfast love and not sacrifice, the knowledge of God, rather than burnt offerings” (Hosea 6:6). This was confirmed by God himself who, through the prophets, accused Israel of cultivating empty gestures that were not accompanied by an in ternal transformation of the heart: “If I were hungry, I would not tell you; for the world and all that is in it is mine. Do I eat the flesh of bulls, or drink the blood of goats? Offer to God a sacrifice of thanksgiving, and pay your vows to the Most High” (Psalm 50[49]: 12-14); or “I hate, I despise your feasts, and I take no delight in your solemn assemblies. Even though you offer me your burnt offerings and cereal offerings, I will not accept them, and the peace offerings of your fatted beasts I will not look upon. Take away from me the noise of your songs; to the melody of your harps I will not listen” (Amos 5:21-23).

In the Old Testament, bloody sacrifices of animals were to be offered by priests to God in order to recognize his sovereignty and obtain his blessing. However, the Temple worship prescribed by the Law also “was always ac companied by a vivid sense of its insufficiency.” The People of God slowly and gradually came to realize that there was nothing that they could offer God who owns everything. God wanted something else….

cisely this crisis situation that brought about a revision of the theology of worship in the Old Testament. It was precisely “the very emptiness of Israel’s hands, the heaviness of her heart, that was now to be worship, to serve as a spiritual equivalent of the missing Temple oblations.” It was Israel’s suf ferings “through God and for God, the cry of her broken heart, her persistent pleading before the silent God, had to count in his sight as ‘fatted sacrifices’ and whole burnt offerings” (SL, 45).

The situation in which Israel found herself coincided with the encounter of the Greek critique of cult as such. This led to the development of the idea of λογικὴν λατρεία (θυσία): spiritual wor ship, worship according to the Logos, that is, according to reason. It is to this idea that Romans 12:1 alludes. In the Old Testament the People of God have finally came to realize that acknowledg ing God’s sovereignty over all things does not consist of destruction, but of something completely different. As Ratzinger states, “[the true surrender to God] consists in the union of man and creation with God. Belonging to God has nothing to do with destruction or non-being: it is rather a way of being. It means losing oneself as the only possible way of finding oneself (cf. Mark 8:35; Matthew 10:39)” (SL 28, “Theology of the Liturgy” (TL), 25).

A turning point came with the Babylonian exile. In a foreign land, there was no Temple, no public and communal form of divine worship as decreed in the law. Israel was deprived of worship and stood before God with empty hands. However, it was pre

At the same time, an important aspect is being added here by Ratzinger, through the influence of his great master, St. Augustine of Hippo. This trans formation leading to union of human beings with God, which is the true and proper sacrifice pleasing to God, is not to be achieved only on the level of individuals, but on the level of community. Therefore, there is a very important ecclesiological component here in Ratzinger’s thought. Augustine teaches that the true fulfillment of the cult takes place when “the whole redeemed human community, this is to say the assembly and the community of the saints, is offered to God in sacrifice by the High Priest who offered himself” (City of God, X,8; see: TL, 25). In other

6 Adoremus Bulletin, November 2022

“ The true surrender to God consists in the union of man and creation with God. Belonging to God has nothing to do with destruction or non-being: it is rather a way of being. It means losing oneself as the only possible way of finding oneself.”

In pre-Christian religions, sacrifice was always associated with destruction and atonement: man, aware of his guilt, want ed to offer to God (or gods) something that would bring him forgiveness and reconciliation. At the same time, these at tempts of arriving at reconciliation with the deity were always accompanied by a sense of inadequacy and insufficiency: the offering could always be only a replacement of the true gift, which is the man himself. Animals or fruits of the harvest could not possibly satisfy God and could only serve as an imperfect representation of the one who offers them.

AB/WIKIPDEDIA. DEPICTION OF THE SACRIFICE OF A YOUNG BOAR, 6TH CENTURY BC.

AB/WIKIPEDIA

words, “the sacrifice is ourselves…, the multitude: a single body in Christ” (TL, 25); “the true ‘sacrifice’ is the civitas Dei, that is, love-transformed mankind, the divinization of creation and the surrender of all things to God: God all in all (cf. 1 Corinthians 15:28). That is the purpose of the world. That is the essence of sacrifice and worship” (SL, 25).

The New Covenant and Eucharist

While linking the animal sacrifices with the idea of worship according to reason/Logos was a step in the right direction, human nature still consists of spirit and body. While the spiritual aspect of cult is primary and essential, human nature still longs for an external expression of this internal submission to God. This is where the Greek concept of λογικὴν λατρεία (“spiri tual worship”) falls short since it does not do justice to the human pscyhosomatic condition—our natural struggle to express our spiritual dimension through physical means. This is where a final fulfillment of this idea arrives with the event of the Incarnation of the Logos, the Divine Son—in which, finally, God and man are met in one person, Christ.

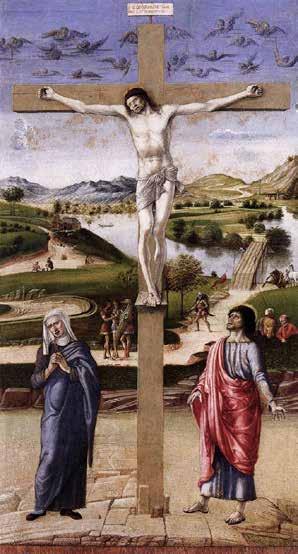

Ratzinger’s theology of Christ’s sacrifice is largely based on his reading of the Gospel of St. John and the Letter to the Hebrews. From Hebrews, Ratzinger takes the idea of Christ’s sacrifice being offered once and for all, at the altar of the cross, with Christ as the new and ultimate High Priest. From John he takes the idea of Christ being also the new temple—it is his humanity that Jesus has in mind when he announces: “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up” (John 12:19). The event of the cleansing of the Temple is more than just an angry outburst against the merchants and the abuses that were taking place at that time. It is “an attack on the Temple cult, of which the sacrificial animals and the special Temple moneys collected there were a part” (SL, 43). Christ’s death on the cross, followed by the tearing of the Temple curtain into two, and then, in years to come by the physical destruction of the Temple, brought an end to the old economy of worship and inaugurated the new one: the true worship will now take place in the new Temple, in Christ himself, who is the dwell ing place of the Father and the Spirit.

Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross, however, is constantly re-presented by the Church when the sacrament of the Eucharist is celebrated. The once-and-for-all event reaches beyond the historical boundaries and spills over to the past and to the present: if we mention Abel, Abraham, and Melchisedek in the Roman Can on as those who also participate in the offering of the Eucharist, then in the celebration of the Mass we are dealing with something more than a simple memorial understood as remembering an important event from the past. As Ratzinger explains, the εφάπαξ, that is, Once For All, is bound up with the αἰώνῐος, that is, everlasting; and the semel, that is, once, bears within itself the semper, that is, always (SL, 56-57).

It is in the context of the Christian celebration of the Eucharist that Paul’s utterance from Romans 12:1

Why St. John Paul II Added the Luminous Mysteries to the Rosary

CNA—Twenty years ago, St. John Paul II published the apostolic letter Rosarium Virginis Mariae, adding five Luminous Mysteries to the traditional 15 meditated on in the rosary.

The Luminous Mysteries refer to Christ’s public life, and are his Baptism in the Jordan; his self-manifestation at the wedding of Cana; his proclamation of the Kingdom of God, with his call to conversion; his Transfiguration; and his institution of the Eucharist, “as the sacramental expression of the Paschal Mystery,” according to the letter.

In his apostolic letter, the Holy Father explained that “the rosary, though clearly Marian in character, is at heart a Christocentric prayer” and that it had “an important place” in his spiritual life during his youth.

In fact, two weeks after being elevated to the Chair of Peter, St. John Paul II publicly confessed: “The rosary is my favorite prayer.”

The pope proposed the Luminous Mysteries to “high light the Christological character of the rosary.” These mysteries refer to “Christ’s public ministry between his Baptism and his Passion,” the Holy Father explained.

Thus in these mysteries “we contemplate important aspects of the person of Christ as the definitive revelation of God,” the pope said, since it is he who “declared the beloved Son of the Father at the Baptism in the Jordan, Christ is the one who announces the coming of the King

needs to be understood. Our “spiritual worship” con sists of our submission to God “in spirit and in truth” (John 4:24). This submission is internal (spiritual), but also physical (bodily)—even if for “body” Paul is using the more generic Greek term σῶμα rather than the more specific σάρξ, there is no doubt that he is talking here about the whole person. This submission of the human person takes place not somehow in isolation, or in parallel with Christ’s submission to the Father represented in the Eucharist, but in deep relation to it. In the Eucharist, the spiritual element

dom, bears witness to it in his works and proclaims its demands.”

St. John Paul II also noted in his apostolic letter that “it is during the years of his public ministry that the mys tery of Christ is most evidently a mystery of light: ‘While I am in the world, I am the light of the world’ (John 9:5).”

Thus, for the rosary to “become more fully a ‘compen dium of the Gospel,’” the pope considered it appropriate that there be “a meditation on certain particularly signifi cant moments in his public ministry, following reflection on the Incarnation and the hidden life of Christ (the joyful mysteries) and before focusing on the sufferings of his Passion (the sorrowful mysteries) and the triumph of his Resurrection (the glorious mysteries).”

The pope stressed that adding the Luminous Myster ies is done “without prejudice to any essential aspect of the prayer’s traditional format, is meant to give it fresh life and to enkindle renewed interest in the Rosary’s place within Christian spirituality as a true doorway to the depths of the Heart of Christ, ocean of joy and of light, of suffering and of glory.”

St. John Paul II explained that each of the mysteries of light “is a revelation of the Kingdom now present in the very person of Jesus.”

This presence is manifested in a particular way in each one of the Luminous Mysteries.

In Baptism, Christ “became ‘sin’ for our sake (cf. 2 Corinthians 5:21),” the Father proclaims him the Beloved Son and the Holy Spirit “descends on him to invest him with the mission which he is to carry out.”

At the wedding at Cana, Christ, by transforming

is combined with the physical component—through the visible signs and actions, invisible, spiritual realities take place. The longings of all pre-Christian religious systems and the Old Testament dynamism of worship are being fully realized in the sacrifice of the Mass where the physical offering cannot be just an empty gesture that may (or may not) express an internal disposition of the person. The person that offers this sacrifice, Christ himself, offers to the Father both his spirit and his body, and into this process of submission in love, the Church is being invited and drawn. The two sides of the same coin, the external offering and the internal disposition, in Christ become the reality, and they are perpetuated in the gift of the Eucharist.

Worship: Reasonable, Spiritual, True Ratzinger’s understanding of the concept of λογικὴν λατρεία in Romans 12:1 is indicative of the way he understands the general relationship between ideas that originate outside of Christianity, and the divine revelation that we know from the Bible and from Tradition. Just as philosophy can prepare the ground for faith (“the God of the philosophers” is at the same time the Biblical God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob), the Greek idea of “spiritual/reasonable worship” can be understood as preparation for the true worship “in spirit and in truth” that comes with the revelation of the Incarnate Logos. Christian scriptures and theol ogy take up those non-Christian concepts and ideas that point to the right direction, and they fulfill them with new meaning, the ultimate meaning that comes with Jesus Christ, the Word (Logos) of the Father.

This fulfillment does not supplement the Christian revelation with something that it would not possess otherwise; but it helps to bring out and articulate those elements that are already there, even if it not always present in an evident way, or even if not perceived with ease. The dialogue between human reason and faith takes place in all areas of theology, including in the area of the liturgy and sacraments. Catholics have been long accustomed to uniting their own offerings with the Sacrifice of the Mass. Ratzing er’s analysis of Romans 12:1 helps us to understand even more the inner relationship that exists between the sacrifice of the altar and our own spiritual of ferings that we bring to the Eucharist, so that the promised worship “in spirit and in truth” (John 4:24) may become an ever fuller reality in our lives.

Mariusz Biliniewicz currently serves as Director of the Liturgy Office in the Archdiocese of Sydney, Austra lia. He has worked at the University of Notre Dame Australia as Senior Lecturer in Theology and Associate Dean of Research and Academic Development. He has studied and worked in Poland, Ireland, and Austra lia, and has spoken and published internationally on a number of theological topics. His interests include contemporary Catholic theology, liturgy, sacraments, the Second Vatican Council, intersections between ecclesiology and moral theology, faith and reason, and general systematic theology.

water into wine, “opens the hearts of the disciples to faith, thanks to the intervention of Mary, the first among believers.”

With the preaching of the kingdom and the call to conversion, Christ initiates “the ministry of mercy,” which continues through “the Sacrament of Reconciliation which he has entrusted to his Church.”

For St. John Paul II, the Transfiguration is the “mys tery of light par excellence” since “the glory of the God head shines forth from the face of Christ as the Father commands the astonished Apostles to ‘listen to him.’”

The institution of the Eucharist is also a mystery of light because “Christ offers his body and blood as food under the signs of bread and wine, and testifies ‘to the end’ his love for humanity (John 13:1), for whose salva tion he will offer himself in sacrifice.”

The Holy Father pointed out that “apart from the miracle at Cana, the presence of Mary remains in the background.” However, “the role she assumed at Cana in some way accompanies Christ throughout his ministry,” with her maternal counsel: “Do whatever he tells you (John 2:5).”

St. John Paul II considers this counsel to be “a fitting introduction to the words and signs of Christ’s public ministry and it forms the Marian foundation of all the ‘mysteries of light.’”

The pope then proposed that these mysteries of light be contemplated on Thursdays.

This story was first published by ACI Prensa, CNA’s Spanish-language news partner. It has been translated and adapted by CNA.

Ratzinger’s theology of Christ’s sacrifice is largely based on his reading of the Gospel of St. John and the Letter to the Hebrews. From Hebrews, Ratzinger takes the idea of Christ’s sacrifice being offered once and for all, at the al tar of the cross, with Christ as the new and ultimate High Priest. From John he takes the idea of Christ being also the new temple.

AB/WIKIMEDIA. GIOVANNI BELLINI (CIRCA 1430 –1516)

7 Adoremus Bulletin, November 2022

“ The longings of all pre-Christian religious systems and the Old Testament dynamism of worship are being fully realized in the sacrifice of the Mass.”

Continued from NEWS & REVIEWS, page 2

Four Centuries Later: A Modern Look at Introduction to the Devout Life

By Anne Koerner Simpson

December 28, 2022, marks the 400th anniversary of the death of St. Francis de Sales. As the bishop of post-Reformation Geneva, he devoted much of his time to reconverting Catholics who had embraced the heretical tenets of the Geneva-based Protestant reformer John Calvin. He accomplished a miraculous number of such conversions through his trademark style of speaking and writing the truth in charity. This gentle approach is found in tracts which he wrote and left at private residences throughout Geneva (because of his effective use of writing media, St. Francis is considered the patron saint of writers and journalists) and he effectively employed the same charitable style in the spiritual direction of souls, preaching, and hearing confessions.

Among de Sales’s works is a classic of sacred literature which has shaped the minds, hearts, and souls since its first publication in 1609, Introduction to the Devout Life. This little book is unique because it is written as a series of instructional letters to a lay woman—the wife of a wealthy courtier. “Philothea” (as de Sales addresses her in the book) is instructed on how to live the life of a holy woman in the world around her, not as a monastic might, but as a regular lady, living a regular life, having regular duties and obligations, including those she owes to her family and children. Francis instructs Philothea on how to live a devout life in a way that balances the needs and realities of ordinary life with the true call to holiness. He does this by outlining a method of living through reconciliation with God, prayer, the sacraments, and virtue.

Introduction is particularly remarkable because it was written to and for the laity, a fact which may seem commonplace today. Of course, in another sense, all who wish to achieve holiness are “Philothea” and this work is for every one of us—clergy, laity, and religious alike. But how does St. Francis de Sales’s advice to Philothea synthesize with modern life? Is a devout life also a liturgical life? How do de Sales’s instructions to be devout accord with the Second Vatican Council’s desires for liturgy to be the source and summit of all the Church’s actions? The word “devout” is something that may cause confusion to the modern audience. After Vatican II, the devotional practices of the Church were tamped down, redirected from the liturgical sphere to a private one, lending to a preference for worship rooted in liturgy.

Both/And

While Sacrosanctum Concilium states “the liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the church is directed” (10), at the same time the document says that the liturgy “does not exhaust the entire activity of the Church” (9). Though the liturgy be the “font from which all her power flows” (10), at the same time, “popular devotions are to be highly commended” (13). Sacrosanctum Concilium notes that the spiritual life, while having its source in the liturgy, is not limited to the liturgy: “The Christian… must also enter unto his chamber to pray to the Father, in secret, yet more, according to the teaching of the Apostle, he should pray without ceasing” (12). This fulsome prayer life is in fact what de Sales mean by “devout life.” It does not mean simply that one practices devotions, nor is it contrary to a liturgical life.

“What is a devout life?” is answered immediately in the opening paragraphs of the book: “Genuine living devotion, Philothea, presupposes love of God, and hence it is simply true love of God. Yet it is not always love as such. Inasmuch as divine love adorns the soul, it is called grace, which makes us pleasing to his Divine Majesty. In as much as it strengthens us to do good, it is called Charity. When it has reached a degree of perfection at which it not only makes us do good but also do this carefully, frequently, and promptly, it is called devotion.”1

In other words, a devout life reflects a soul who, through love, conforms her life to God and habitually chooses the good. Charity is the source of devotion. De Sales writes, “Charity and devotion differ no more from one another than does flame from the fire. Charity is a spiritual fire and when it bursts into flames it is called devotion. Hence devotion adds nothing to the fire of charity except the flame that makes charity prompt, active, and diligent not only to observe God’s commandments but also to fulfill his

heavenly counsels and inspirations.”2

The foundational paragraphs of Introduction clearly express that a devout life is a life rooted in prayer and sacraments which then out of habitual charity lives a life of virtue, transforming the soul into union with God. This is applicable to all persons, no matter their state in life. De Sales’s term, “devout,” should in no way be associated with something contrary to modern ideas of a sacramental, liturgical life. These truly are the same. To illustrate this further, his methods for achieving a devout life should be examined.

Steps to Christ

The first step in the method is the choosing of Christ. This seems the simplest of all things but is profound in action because the turning of one’s life toward the open arms of Jesus Christ is simultaneously the turning away from and rejection of a life of sin. De Sales details a process of purgation of the soul whereby a series of meditations draws the heart to step into God’s grace and live without reproach. This section culminates in instruction for sacramental confession.

Once the soul has turned toward God and turned away from sin and the attachments to sin, the second part of this method is the life of prayer. “Just as little children learn to speak by listening to their mothers and lisping words with them, so also by keeping close to our Savior in meditation and observing his words, actions, and affections we learn by his grace to speak, act, and will like him.”3 He says the subject of our meditations should be the life and passion of Christ. “His life and death are the most fitting, sweet, wonderful and profitable subject that we can choose for our ordinary meditations.”4

Prayer is divided into vocal prayer and mental prayer. In addition to classic vocal prayers in Latin, he encourages the learning of these prayers in the vernacular so that one may meditate upon them and understand them better. He lauds the rosary as a useful prayer when recited properly, taking care to learn the method of recitation through the “little books that teach us the way to recite it.”5 In both ways, he does encourage the intelligent worship that was the desire of the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council.

Towards the end of this rich second part on the subject of prayer is a section on the attendance at Holy Mass. While it seems to be the third step in his method, it is clear by his writing that this is truly the source and summit of the devout life. “Thus far I have said nothing of the sum of all spiritual exercises—the most of divine charity, the mystery in which God really gives himself and gloriously communicates his graces and favors to us. Prayer made in union with this divine sacrifice has inestimable power, Philothea, so that by it the soul overflows with heavenly favors… make every effort therefore to assist every day at holy Mass so that together with the priest you may offer up the sacrifice of your Redeemer to God his father for yourself and for the whole church.”6

December 28, 2022, marks the 400th anniversary of the death of St. Francis de Sales. As the bishop of post-Refor mation Geneva, he devoted much of his time to reconvert ing Catholics who had embraced the tenets of the Genevabased Protestant reformer John Calvin. He accomplished a miraculous number of such conversions through his trade mark style of speaking and writing the truth in charity.

AB/LAWRENCE

OP ON FLICKR

It was not a common practice during St. Francis de Sales’s time to receive communion frequently. Not until Pius X pub lished his 1905 decree Sacra Tridentina was frequent communion encouraged such as we practice it today. Yet Francis de Sales was a supporter of at least weekly communion, if not more frequently, according to the individual and his spiritual director. It was de Sales’s view that reception of this sacramental food which nourishes and sustains the soul should not be denied if the soul is in the state of grace to receive it.