3 minute read

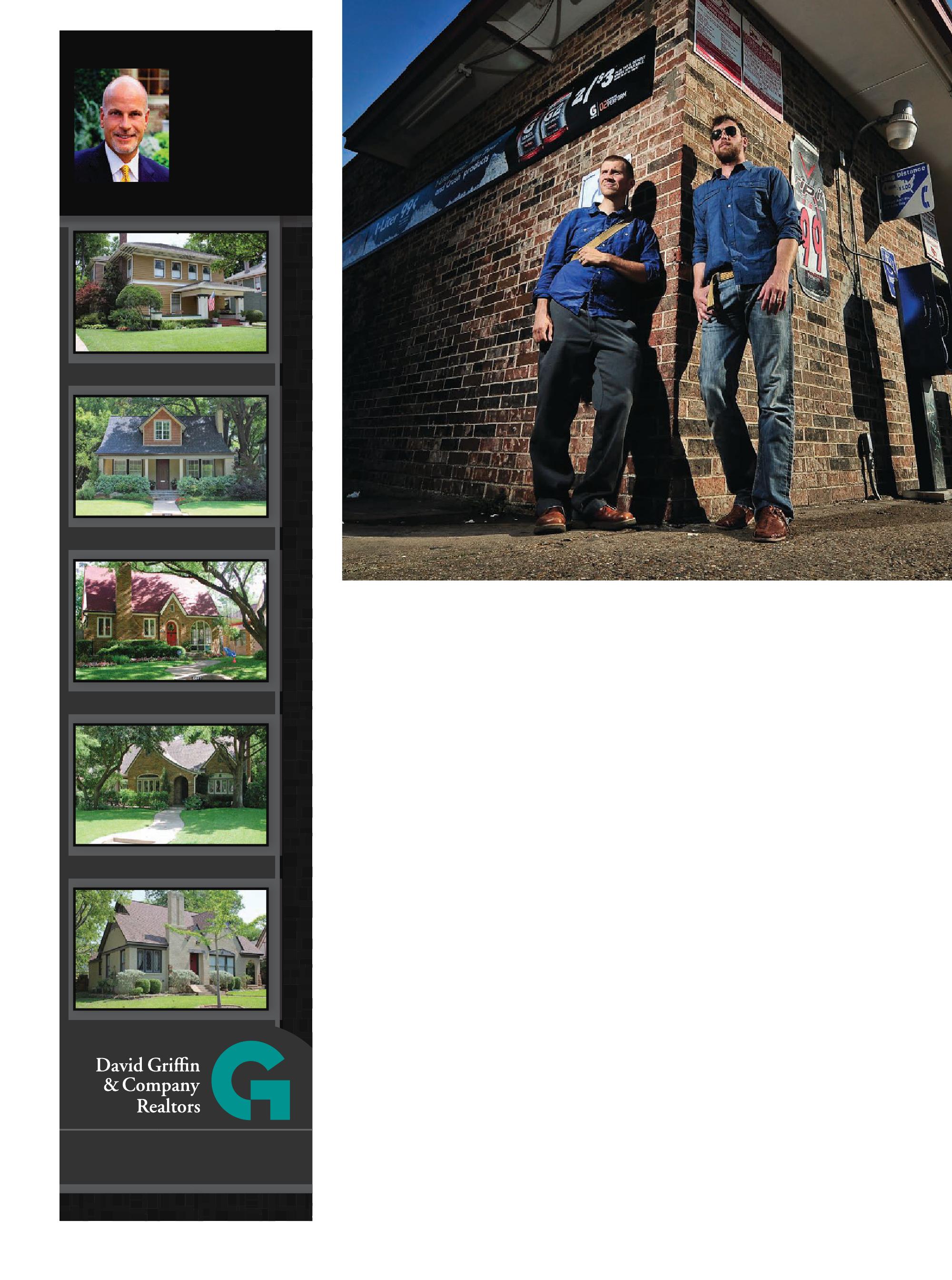

Las Manos Negras

Neighborhood artists highlight wage theft among undocumented workers

Story by RachelStone | Photo by Can Türkyilmaz

Injustice can come in the form of a desperate couple, on their last few gallons of gas, searching for another check-cashing place. One that might somehow hand them their pay instead of the dreaded “insufficient funds” notice indicating their boss stiffed them on a week’s salary.

Old East Dallas residents Scott Gleeson and Dane Larsen say that in the course of researching their current art project, “Las Manos Negras,” they encountered this couple, migrant day laborers whose boss bounced a check to them and other workers on the job, according to the story. Stories like these, of wage theft, undocumented laborers and the system that exploits them, are the basis of “Las Manos Negras,” which received a $4,000 Idea Fund Grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Many elements comprise the project, starting with an oral history. Larsen, who has lived in the Dominican Republic, records interviews with the workers. Another story, for example, is of a gardener who was brutally stabbed in a hate crime while working in DeSoto. The hospital sent him a bill for $10,000.

The interview, on an MP3 player, is placed in a box meant to symbolize a toolbox, which is inside a vintage lunchbox. Other compartments in the toolbox hold documents, such as medical records and pictures from the knife attack, as well as a cast molding of the inside of the worker’s clenched hands so that observers can hold the molds and feel the imprint of the hands that held the hammer.

The Warhol Foundation told Gleeson and Larsen their project perfectly fits the criteria for the grant, which is offered only to Texas artists. The grant supports experimental public artwork that seeks to reach an audi- ence outside the art and academic worlds.

The intended audience for “Las Manos Negras” is not the gallery-going public. It is for day laborers and migrant workers themselves. The artist team, which also includes Justin Shull of Santa Monica, Calif., wants the project to empower the workers to seek justice.

Wage theft is a problem that is rooted deeply in our economic culture, says Cristina Tzintzun, executive director of Austinbased Workers Defense Project, which is a sponsor of the art project.

“There are industries that have so many layers of subcontractors, and there is a lack of transparency and accountability,” Tzintzun says. “Sometimes we see projects worth hundreds of millions of dollars where workers aren’t paid.”

Workers Defense Project studies show that one in five day laborers in Austin had not been paid for their work at least once in the past five years, Tzintzun says. And there is little legal recourse for wage-theft victims. The Texas Workforce commission can order an employer to pay its workers, but most workers are unwilling to pursue that course because they fear deportation.

Most of the $4,000 from the Idea Fund Grant is going toward paying subjects for their interviews, usually about $80 each, a fair day’s wages. The artists chose to pay the workers as a symbolic gesture and to lessen exploitation of them, although they don’t reveal the money part until after the interview is over. Art has a history of exploiting marginalized members of society, says Gleeson, who until recently was working on a doctorate in art history at Southern Methodist University. The artists are avoiding exploitation, including photography of any kind.

Besides that, bringing cameras to a day labor site is the quickest way to make men scatter.

“One of the biggest challenges we’ve had is just getting people to talk to us,” Gleeson says. “The fear of speaking out is our biggest obstacle.”

The artists also are raising money for the project through posters, woodcuts based on images and themes from the Mexican Revolution. Paper Arts on Peak is making the prints, which cost $25 each.

The artists don’t see an end to the problem of wage theft among day laborers, and they don’t see an end to their project. They would like to document as many stories as possible, each one costing about $150 and dozens of hours of work.

Gleeson conceived of the project while he was still a graduate student. He had to ask himself: Is it better to research and write about art for an academic audience, or is it better to do artwork and send a message to the public?

He decided on the latter, and he was inspired by day laborers he noticed on Ross Avenue. Larsen is a friend of Gleeson’s wife from their days at Booker T. Washington High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. Larsen and his wife lived for a while in Thailand, where they taught English as undocumented workers. He once worked as a gardener in Austin and sometimes hired undocumented workers. So he’s seen both sides of the story firsthand.

“I conceived of the project with Dane in mind,” Gleeson says.

The project is touchy, politically and legally, and it’s antagonistic. Most public art creates a picture of unity. This project shines a light on the separateness of cultures. “Wage theft is a way of implicitly saying, ‘We don’t want you here,’ or at least, ‘We don’t care about your well-being,’ ” Gleeson says.