6 minute read

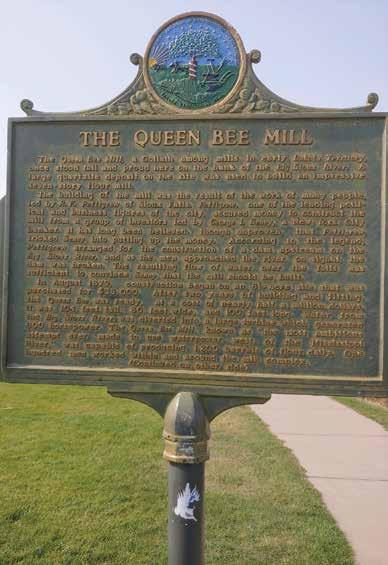

The Queen Bee Mill

title

The Queen Bee Mill

BY WAYNE FANEBUST

The Queen Bee Mill was the brainchild of R. F. Pettigrew, a Sioux Falls man with an appetite for big spending and building. By taking on the mill project, he was actually carrying out the ideas of the first white speculators who gazed in wonderment at the Falls of the Big Sioux River, awe-struck and amazed at the raw power of the water. It was said that a man from Maine became “halt mad” in the presence of the Falls and the roaring waters that overcame the quiet of the surrounding prairie. The first territorial governor of Dakota, William Jayne, said in his address to the legislature that the Falls of the Big Sioux River had the ”motive power to drive all the mills of New England.”

Pettigrew recalled the time he was impressed by the sight of a long line of wagons, filled with wheat, creaking their way into Sioux Falls. There were mills on the Big Sioux River including the Cascade Mill, situated above the first cascade of the Falls, but Pettigrew wanted more. He understood that as time went on, more settlers would claim land and start farming, meaning the amount of crops grown would increase. A Sioux Falls newspaper printed a pamphlet that claimed Dakota Territory would grow wheat “as successfully as water rolls down a hill.” Pettigrew had similar beliefs and he decided that Sioux Falls needed a large and powerful mill to grind the valuable crop that the land was producing. Besides, a large, state-of-theart mill would put Sioux Falls on the map and in the minds of skeptical outsiders.

Pettigrew began making plans for such a mill to exploit the power of the Falls. One of the first steps was go get the property owners, W. W. Brookings and Dr. Josiah L. Phillips, to sell the proposed mill site to a group of New York City investors. Then June 2, 1879, it was announced in a Yankton newspaper that the mill property was about to be sold for $45,000.00. A month later, a Sioux Falls newspaper announced that banker George I. Seney, a New York capitalist and art collector, was the leading man in the group of investors, and that negotiations were ended and the deal closed. A company was formed to construct and own the Queen Bee Mill, and Pettigrew and Brookings were among the owners.

The 81-acre purchase included the

R. F. Pettigrew

Falls and a heavily wooded island that the early settlers named “Brookings Island,” after W. W. Brookings, who claimed the beautiful piece of nature under a federal law known as the Pre-emption Act. Having paid only $1.25 per acre meant he made a bundle. His friend, former Dakota governor Newton Edmonds, also made a good haul. From a $60.00 investment in 1872, he walked away with $9500.00. Pettigrew also made a nice profit; money that he used to further his political goals.

Not everyone was happy, however, for there was a small minority that wanted to preserve the area in its natural condition for a city park. These dreamy-eyed folks sensed an opportunity to create a city park for Sioux Falls that would rival Central Park in New York City. The idea failed to get any traction, and Sioux Falls was forever denied the chance to create a magnificent park that would have embraced the Falls and the wooded island that was renamed “Seney Island,” in honor of the New York City banker. A wealthy stranger, cast his gilded net onto the Dakota frontier, and purchased a one-of-a-kind slice of natural beauty that should have been retained by the people and preserved in its natural state for all time to come.

But it was not to be and the process moved forward. It seemed as if the world was watching Sioux Falls and its fabulous Falls, for when construction was started, a party of dignitaries, an estimated 500 people, some coming as far away as London, gathered at the site to witness the first dynamite blast in the quartzite stone

that was used to build the thick-walled, seven story structure. It was a spareno-expense extravaganza that included state-of-the-art machinery that everyone believed would grind wheat into flour, and bring unparalleled prosperity and prestige to Sioux Falls.

It has been rumored that Pettigrew tricked Seney into putting up the cash for the mill. It was said that Pettigrew had a dam built somewhere up river from the Falls. He invited Seney to Sioux Falls and when the New York tycoon was at the site of the proposed mill, the dam was broken and a thunderous wave of water flowed over the Falls, thus convincing the banker to bank roll the project.

The story is false, for there is no evidence that George I. Seney ever visited

Sioux Falls. Had a man of his stature set foot in Dakota, every newspaper in the territory would have bragged about the presence of such a prominent man. Not only that, Pettigrew had a reputation for being an honest businessman, and was not one who wanted to waste money. Pettigrew had dealings with Seney after the Queen Bee fiasco, something that probably would not have happened had there been trickery.

Construction on the mill that would be named the Queen Bee Mill began in August of 1879. It took two years to complete the quartzite giant. The interior featured two miles of elevators, three miles of conveyors and ten miles of belting. First floor offices had speaking tubes so that there could be communication with the mill workers. The total cost of construction

was close to $500,000.00.

After withstanding the terrible flood in the spring of 1881, the grinding of wheat into flour began on October 25, 1881. The “Queen Bee” was the featured brand of flour, with other brands such as “Jasper” and “Nellie Bly.” Despite the high expectations for the Queen Bee Mill, it went bankrupt and by 1883; and production stopped. Creditors were not paid and investors failed to turn a penny of profit. The water power proved to be insufficient during parts of the year and the supply of wheat was far less than was expected. The region was not wheat country after all. Other crops such as corn and oats were more successfully planted. It was a colossal failure, and owing to its large size, the Queen Bee was a constant reminder of a multitude of mistakes by well-meaning people.

There were other losses. Seney Island, a place of singular beauty, where the pioneers camped, held picnics and 4th of July celebrations, disappeared. The channel was filled with debris and dirt to accommodate a railroad. The loss of that scenic island is incalculable.

There were other attempts to make the Queen Bee work, but by the end of World War I, it ceased entirely. Over time other businesses moved into the thick-walled monarch that seemed to be scowling down in mockery at the many dashed dreams that were scattered at its feet. Finally, a fire gutted the interior of old Queen on January 30, 1956, leaving a shell of stone, a fascinating relic of the past, a portion of which is still standing and has become a beloved feature of Falls Park.