7 minute read

The Amidon Tragedy

title

The Amidon Tragedy

BY WAYNE FANEBUST

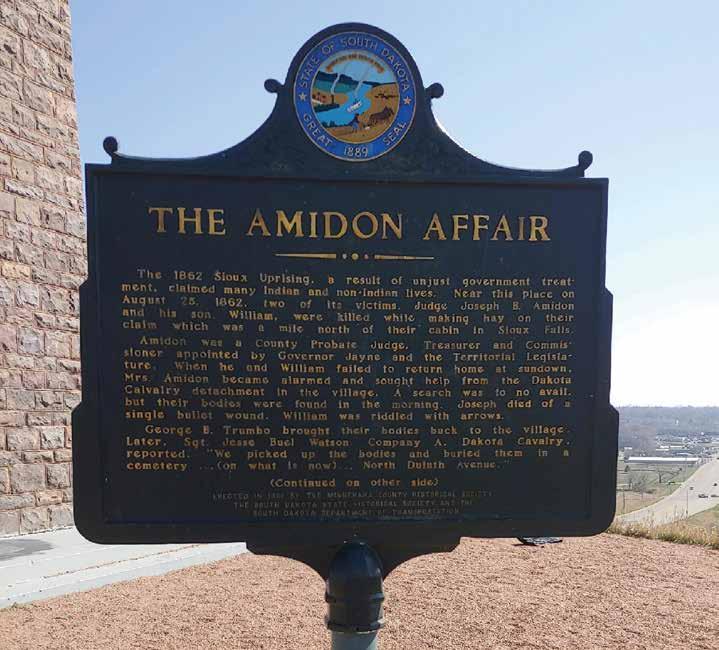

Much of early Sioux Falls and Dakota Territory history is shrouded in mystery. Names appear in the record and our curiosity is aroused. Those of us who seek to uncloak the mystery, instinctively react and research; we ask questions. We wonder: who were these people and why did they come here? Did the pioneers look at the raw land and see city as we may look about us and try to see the land as it once was in its natural state? Was their forward looking vision more creative than ours as we look back and try to recapture some of that which has been lost over the span of time? Is our desire to interpret and write about the past and its people as great, or greater, than the desire of our ancestors to tame the wilderness and put to work for mankind?

In 1857, a party of speculators from St. Paul, calling themselves the Dakota Land Company, arrived at the falls of the Big Sioux River with the intent to claim it and use the landmark as a centerpiece for their town. But they found that the falls had been claimed the year before by a rival company from Dubuque, Iowa. The name selected for their town site was “Sioux Falls.” Undaunted, the St. Paul men claimed 320 acres of land next to the claim of the Iowa men and called their

Chief Little Crow of the Santee Sioux

plot of land “Sioux Falls City.” The rival companies decided to pool their resources and start building. It wasn’t long before settlers arrived.

Among the early arrivals at the Falls was Joseph B. Amidon, an erudite easterner who had been living in St. Paul with his wife Mahala, son William and daughter Eliza Jane. The Amidons had lived in Vermont and New York prior to moving to the West. William, usually referred to as Willie, and Eliza Jane were just two of four children who lived to become adults. Six others died in infancy. The strain of losing so many children must have weighed heavily on Amidon’s first wife, Emma Morse of Dorset, Vermont, for she died back East. On October 5, 1855, Joseph married Mahala St. John Drake in St. Paul. In 1858, the year Minnesota was granted statehood, the four Amidons left St. Paul for their new home in Sioux Falls.

The Joseph and Mahala Amidon claimed land on the left bank of the Big Sioux River, below the falls where a creek drained into the river. They built a small house near the claim, above the falls, using rough quartzite stone. The location of the house is marked on the hand-drawn map of the town site. Willie’s claim was to the north of his parents on ground that sloped upward to the top of the great bluff that partially ringed the fledgling town site.

In 1861, when Dakota Territory was created by Congress, and county governments were established, the elder Amidon was selected to be the probate judge of Minnehaha County, and son Willie was elected to the office of county commissioner. Having the public trust along with the rich soil, abundance of water and scenic beauty everywhere, the transplanted easterners must have felt especially blessed.

Judge Amidon was described by his daughter Martha Amidon Seaman as a man of high character who was devoted to the common good. He was an upright, honest and a courageous God-loving man, natural leader who led from the heart and with only the best intentions. Having experienced the loss of so many loved ones, he suffered from depression, but he never let his personal problems cloud his judgment nor did the mental maladies ever overshadow his love for his family. Joseph B. Amidon was a brave man who feared no man or beast and

Judge Amidon’s Daughter Martha

yet he owned no guns and had “never fired a gun in his life.”

In the summer of 1862, Sioux Falls consisted of fifteen dwellings, none of them fancy, along with a newspaper office that periodically produced the Dakota Democrat, a blacksmith shop and a saw mill. There was also a “hotel” called the Dubuque House, made of rough stone, but the crude structure was not well patronized. That summer a contingent of horse soldiers, Company A, Dakota Cavalry from Yankton was temporarily encamped at Sioux Falls because of disturbing reports of Indian trouble in Minnesota. The Civil War raging full force in the East and South, but the small, isolated Dakota prairie town seemed to be basking in peace and quiet. It is doubtful that anyone in the area was well-armed.

All that changed on August 25, 1862. That morning the judge and his son set out in an ox-drawn wagon to cut hay for the government on Willie’s claim. As they expected to be out all day, they packed a lunch. Unfortunately they failed to return home that evening and were never again seen alive.

A neighbor, Berne C. Fowler heard gunshots from up on the bluff about 4 o’clock that afternoon. Thinking it was Willie shooting at blackbirds, Fowler recalled saying “I wish Willie Amidon would not send the blackbirds down to my corn.” Mahala had prepared supper for her husband and stepson, but as they failed to appear she became frantic with fear. In the dark, she made her way to the soldier’s camp in the company of her large dog. She pleaded with the officers of the camp to make an effort to find the missing men. Although they were fearful of being attacked by Indians, a contingent of soldiers searched the area, found the wagon and oxen in a shed, and the empty

Map of Sioux Falls City, August 29, 1862

lunch pails, but no sign of the two men. They returned to camp with a view of returning to the bluff in the morning and make another search.

At sunrise the next day the soldiers resumed their search. Mahala, who had spent the night in fear with only her dog for company, watched the horseman move up the bluff until they were out of sight. She kept her eyes on the bluff until she saw a single rider galloping back to the town site. The news was bad. Both men were found dead in the cornfield; Joseph shot three times and Willie seven times by combination of bullets and arrows. It was believed that Willie had left the hay meadow and went into the cornfield to chase off a flock of blackbirds. In so doing, he accidentally came upon a group of Indians, led by Sisseton Sioux warrior White Lodge, who were sent by Chief Little Crow to attack and drive out the settlers.

The entire settlement was united in mortal fear but they gave the Amidons a proper burial, next to the grave of Henry Masters, who died in 1859. The handdrawn map of Sioux Falls City shows the location of the three graves. On August 29th, Sioux Falls was abandoned. The entire population hastily loaded up food and supplies and headed for the safety of Yankton, the territorial capital. In a letter to her daughter Martha, Mahala Amidon said: “It was the hardest thing for me to leave your father there. I can’t bear to think he lies in that desolate place, with no friend to even visit his grave.”

It seems very unlikely that Mahala ever returned to Sioux Falls to visit the graves of her husband and stepson. But there is a note from a Sioux Falls man, in 1881, that confirms the bodies of the two men were exhumed from the graveyard on what is now North Duluth Avenue, and reburied in Mt. Pleasant Cemetery, in unmarked graves.

recipes 23

Last Day of School Treats

at home 24

The Mike May Home

vino 34

Your Mom Deserves Nice Stemware

man in the kitchen 38

Reemerging into Society

knick knacks of life 44

How to Spend Our Limited Time? A Mom’s Conundrum

health & well-being 46

Can Essential Oils Help with Seasonal Allergies?

nest