Recently, as I reviewed the many excellent aviation-oriented posts on LinkedIn, I was struck by the number of open positions available with many aviation businesses, including insurance firms. From brokers to underwriters, service providers and beyond, the demand for talent in our industry has never been higher as companies in every sector seek to position their businesses for success.

According to a report published by Allied Market Research, the global aviation insurance market is expected to grow to over $5.7 billion by 2030. Over this same timeframe expected advances in advanced air mobility, alternative fuels, electric aircraft engines and more, will create an increasingly dynamic aerospace environment. Air travel has rebounded strongly; according to a recent IATA report, passenger numbers are expected to reach 83% of pre-pandemic levels by the end of 2022 and return to or exceed 2019 levels by 2024.

At the same time aviation is becoming safer. While the impact of COVID-19 reduced the number of GA hours flown, NTSB statistics show the fatal accident rate per 100,000 flight hours nevertheless fell again in 2020 to 1.049 from a 2019 rate of 1.064. There were no U.S. airline fatalities in 2020 or 2021

as has been the case for seven of the last 10 years. Advances in avionics, manufacturing processes, and materials technology hold the potential for continued improvements in aviation safety in the years ahead.

The demand for pilots — both GA and airline — is the highest it’s been in recent years. Several carriers have responded to this challenge by vertically integrating flight training into their core business model. Republic’s LIFT and United’s AVIATE are two such examples. Flight training at America’s FBOs and GA schools has increased significantly, and enrollment at aerospace universities such as Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, University of North Dakota, and others is at an all-time high.

When I (and my trusty E6B) graduated from Embry-Riddle in 1983, the aviation jobs market was, well let’s just say, “not robust.”

The aviation industry and the nation at large were just beginning to recover from a deep recession where gas prices climbed, agricultural exports declined, crop prices fell, and interest rates rose. While some might correctly point to many of these same conditions as being present in our current economy, the aviation jobs market is booming and seeking talent in all areas to meet current and future needs.

Despite the advances in aviation activity, safety, and technology, the aviation insurance market is not without financial headwinds. Environmental, economic, political, societal, or technological “black swan” events are almost impossible to predict and hold the potential for significant market impact. As superbly outlined by several of our keynote speakers in Nashville, the effects of social inflation and nuclear verdicts will continue to present challenges in pricing, forecasting, and claims handling. Added to these are the effects of inflation on aircraft values and repair costs. But despite their impact, the very presence of these challenges increases the need for aviation

Jobs Board that will provide visibility for candidates — both internal and external to the industry — to aviation insurance career opportunities. It will also provide an industry overview to help job seekers answer the question, “Why aviation insurance?” and will allow AIA member firms to post opportunities for open positions and internships. Watch for further news on this coming soon.

Thanks to the hard work of your AIA Education Committee (lead by Tim Bonnell Jr.), we’ve also expanded our educational offerings to include a new Introduction to Aviation Insurance course. Designed to

Advances in technology, increasing activity and global mobility demand — together these factors have created an aviation jobs market unlike anything seen over the past 20 years

insurance professionals who are capable of safely navigating their businesses and clients through turbulent conditions.

Advances in technology, increasing activity and global mobility demand — together these factors have created an aviation jobs market unlike anything seen over the past 20 years, including an unparalleled demand for insurance professionals to assist pilots, aircraft owners, and aviation business in managing current and emerging aerospace risk. That’s why your AIA is working to develop an online aviation insurance

provide new professionals and deciding candidates with sound foundational

information, the first program was presented in Atlanta in August, earning rave reviews. More will follow.

In support of careers in aviation insurance, both our Young Professionals and Women’s Initiative programs (lead by AIA Treasurer Luke Uithoven and Director-at-Large Nicole Stout) are moving forward in full force. In the spirit of the old Chinese proverb, “To know the road ahead, ask those coming back,” both groups are exploring ways to connect current professionals and candidates in these

demographics with AIA member mentors to assist them in their career development and decision making. As they were last year, both groups will again be spotlighted at our November AIA reception in London. Finally, there are also ways each of us can help drive interest in aviation and build our own industry’s bench strength. Recruiting the next generation starts at the grassroot level, and you can help simply by sharing your own story. Volunteer to speak at a high school career day. Support and attend programs like EAA’s Young Eagles, AOPA’s You Can Fly, COPA’s Discover Aviation, WAI’s Girls in Aviation, and others. For so many in our industry, aviation is and has been a life-long passion. And while the old saying goes, “You don’t choose insurance –Insurance chooses YOU,” I’ve learned that’s not always the case.

Before the pandemic I had the honor of speaking to a group of Insurance and Risk Management students in the University of Georgia’s Terry School of Business. This program – led by my friend Dr. Rob Hoyt – is one of the best of its kind in the country. I stood in an auditorium filled with more than 100 students who had chosen insurance and was blown away by their level of engagement and enthusiasm.

I asked them the simple question, “When you were little, what did you want to be when you grew up?” As you might expect not one of them mentioned insurance professional. Instead, their answers ranged from policeman to fireman, sports athlete

to musician, truck driver to doctor. Two of them even said pilot, to which I replied, “Meet me after class!” But the great thing about insurance is no matter what you wanted to be when you “grew up,” there’s an insurance industry that aligns with that passion: municipal P&C programs, sports and entertainment, medical, transportation, and many more.

For those who share our passion for aviation, the aviation insurance industry offers a singularly unique career opportunity. And there’s a sign in its window that says, “Now Hiring!”

Fair Skies & Tailwinds,

Greg Sterling is senior vice president and product line manager for light aircraft and U.S. airports for AIG Aerospace. An instrument-rated private pilot, his aviation insurance career spans more than 35 years in various roles. He assumed the position of AIA president in 2021.

For the purposes of this article, we will assume that a single engine aircraft lost power shortly after takeoff and crashed. The pilot was severely injured and the three passengers were killed instantly. There was no damage to any other property and there were no injuries to any person outside the aircraft. No relative of the pilot or any of the passengers witnessed the crash.

You are handling this claim on behalf of the maintenance facility that performed the last annual inspection. The maintenance facility has a liability policy with a liability limit of $1 million per occurrence and a sub limit of $100,000 per person.

From preliminary investigation you have discovered the following information about the crash victims:

• The Pilot, age 50, has a wife and two minor children. As a result of the accident, he has permanent injuries.

• Passenger 1, age 50, is survived by his wife and two minor children. He also has two other minor children with two other women.

• Passenger 2, age 70, was divorced and has no children. He is survived by his adult sister and the three minor children of his deceased brother. At the time of his death, he was hosting a 15-year-old exchange student. His will leaves all his property to his best friend Bob.

• Passenger 3, age 16, was unmarried and a foreign exchange student. His parents pre-deceased him and his legal guardian lives in Europe.

In Part 1 of this article, I discussed the need to ensure that all potential claimants are accounted for and that the court has approved the settlement of all claims of the minor claimants. In Part 2, I discuss the need to ensure that all potential claims for contribution and indemnity have been addressed.

Assuming all claimants release all claims against the insured, this does not fully protect the insured. It is also necessary to protect the insured from potential claims for contribution and indemnity from cotortfeasors as more fully set forth below.

A successful tort claimant can obtain a judgment for both economic losses — medical expenses, lost wages, loss of earning capacity, etc. 1 and noneconomic losses — pain and suffering, loss of care, comfort and society, etc.2

Under California law, a negligent tortfeasor is generally liable for noneconomic losses only in proportion to such tortfeasor’s percentage of fault.3 However, a tortfeasor can be forced to pay for all economic damages, even if only minimally at fault. 4 For example, if a maintenance facility is found 1% at fault and a pilot is found 99% at fault, a

passenger plaintiff free from fault can collect only 1% of the non-economic damages from the maintenance facility, but can collect all of the economic damages from the maintenance facility even if the pilot is solvent.

However, the maintenance facility can obtain a judgment for contribution against the pilot for the excess amount it has become obligated to pay.

5 A claim for contribution

can be made in the plaintiff’s action or can be prosecuted by a separate action after settling with the claimant or after judgment is rendered. 6

No settlement—case goes to trial

To illustrate these principles using the scenario outlined in Part 1, let’s assume that the claimants of Passenger 1 file a lawsuit against the pilot and the maintenance facility and the case goes to trial. At trial the jury makes the following findings:

Fault of the maintenance facility: 10%

Fault of the pilot: 90%

Non-economic damages: $7 million (70% of the total)

Economic damages: $3 million (30% of the total)

In the absence of a settlement, the passenger claimants obtain a judgment

for non-economic losses against the maintenance facility for $700,000 and against the pilot for $6.3 million. Each is liable only for its own percentage of fault.

For the economic damages, however, the passenger claimants will obtain a judgment against both the maintenance facility and the pilot, jointly and severally, in the amount of $3 million; the passenger claimants at their election can collect all from one defendant or some from each.

To mitigate the harshness of this result, California law allows each defendant to obtain a judgment for contribution against the other in proportion to the fault of the other. In this example, the maintenance facility can obtain a judgment for contribution against the pilot for $2.7 million and the pilot can obtain a judgment against the maintenance facility for $300,000.

Any amounts paid to the passenger claimants are credited against this

amount. For example, if the maintenance facility pays $250,000 toward the economic losses, the pilot’s contribution claim is reduced to $50,000.

Maintenance facility settles with passenger 1 claimants—case goes to trial

Now assume that before or during trial, the maintenance facility settles with the claimants of passenger 1 for $400,000 — $100,000 from the insurer and $300,000 from the maintenance facility. Does this protect the maintenance facility from further liability exposure? The answer is no.

Of the $400,000 paid in settlement by the maintenance facility, only 30% or $120,000 is credited toward economic damages. 7 The maintenance facility can therefore be liable to the pilot for contribution in the amount of $180,000.

Maintenance facility settles with passenger 1 claimants — contribution claims are cut off

Assuming the claimants have agreed to a settlement amount from one party, there is a procedure to cut off the rights of others to seek contribution. The settling party can file a Notice of Proposed Settlement and serve it by certified mail or personal service on the parties to be bound. Any non-settling party

component parts, and any fuel supplier who might be a potential target.

The determination of the settlement’s good faith will be made on the basis of information available at the time of settlement. The settlement figure must not be grossly disproportionate to what a reasonable person,

can then file a motion to contest the good faith of the settlement. With or without such a motion, the court can evaluate the settlement and other materials presented and determine whether the settlement is in good faith under the statute. A court decree that the settlement is in good faith bars the non-settling parties’ rights to contribution from the settling party. Each party to be affected by the decree must be given notice of the proposed settlement and an opportunity to be heard on the issue of good faith. Otherwise, such parties could later argue that they were deprived of the opportunity to contest the settlement. The better practice is to provide notice to all persons and entities who might possibly be sued by the plaintiff. In this case, that would include the aircraft and engine manufacturer, any manufacturer or supplier of pertinent

at the time of the settlement, would estimate the settling defendant liability to be. A settlement for insurance policy limits will not necessarily be considered to be in good faith. 9

A party contesting the good faith of the settlement has the burden to show that the settlement is not in good faith. However, if the court finds that the settlement figure is so far out of the ballpark as to be inconsistent with the equitable objectives of the statute, then the settlement is not in good faith. 10 In such case the claimant(s) and the insured/insurer are free to negotiate further and submit a new proposed settlement for approval. Alternatively, the settling party can negotiate a separate settlement with the non-settling part(ies) to resolve the contribution and indemnity claims.

While it is important to obtain a determination of good faith settlement, it may not be appropriate to demand that a good faith determination be a condition of the policy limits settlement. Otherwise, the claimants could contend that the policy limits offer was rejected, then prosecute the claim and obtain a verdict in excess of policy limits, which could subject the insurer to a bad faith claim.

In some cases, it will be in the insured’s best interests to settle with the claimant and take the risk that the settlement may not be found to be in good faith. In most instances the settlement will be upheld as a good faith settlement, and this will cut off any further liability for the claim. If not found to be in good faith, it will cut off all further liability for noneconomic damages.

On the other hand, there may be some situations where the insured would have a legitimate objection to having the insurer pay the policy limits while leaving open the possibility of a claim for contribution and indemnity. The pros and cons of each option should be carefully explained to the insured so that all possible outcomes and the insured’s input may be considered. In some cases, the insured should have the right to veto a proposed policy limits settlement.

The bottom line is that there is not a one-sizefits-all solution, and any potential settlement calls for careful consultation with the insurer and the insured with the involvement of legal counsel. Any decision as to how to proceed should be made only after full disclosure to the insured of all risks and benefits, and only after strongly encouraging the insured to obtain separate counsel at the insured’s own expense.

One alternative is to enter into the policy limits settlement with no contingency that the settlement will be found to be in good faith. This would cut off any further claim of liability to the plaintiffs but leave the insured potentially vulnerable to a claim for contribution from the cotortfeasor(s). This may be acceptable to the insured, as it would minimize the exposure to a huge verdict and leave open the possibility of a good faith settlement. The insurer would then pursue a court determination of good faith, which, if granted, resolves the issue. If the good faith determination is not granted, then the insurer can continue to defend the insured with the express understanding that no further indemnity would be payable beyond the policy limit.

Another alternative is to make it a condition of the settlement that the claimant will not oppose a Determination of Good

there is not a onesize-fits-all solution, and any potential settlement calls for careful consultation with the insurer and the insured with the involvement of legal counsel.

Faith nor join in any opposition to such determination. Once again, the insurer would agree that if the good faith determination is not granted, then the insurer will continue to defend the insured with the express understanding that no further indemnity would be payable beyond the policy limit.

Under any scenario, it is important to ensure that the insured is protected, is kept informed of all settlement discussions, and is given an opportunity to be involved in those discussions.

Getting the claimants to accept a policy limits settlement, with or without a contribution from the insured, is only the first step in getting the insured fully protected from any actual or potential claim. It is important to ensure that all potential claimants are identified and dealt with, that all settlement agreements are enforceable, and that all claims for contribution are barred. Only then can the insurer close the file.

CAVEAT: This article is written to provide general information only and is not to be considered legal advice for any specific factual scenario. Moreover, this article is uniquely tailored to California law; the laws of other jurisdictions can vary substantially. For any particular situation, it is important to consult with a qualified attorney admitted to practice in the appropriate state.

Jon Morse is a Construction, Wrongful Termination and Aviation Attorney at the Morse Law Group. He has been an attorney for more than 35 years, admitted to practice in California and Washington and specially admitted in 18 other states. He has supervised litigation in three foreign countries (Canada, Australia and France).

In Part 1 of this article, I described the potential wrongful death claimants for Passenger No. 2, the gentleman who was divorced and had no children. His heirs are his sister and the children of his deceased brother, and his will left everything to his good friend Bob. I stated that if Bob was a registered domestic partner, then Bob would have a wrongful

death claim and his heirs would not. That was incorrect. Under those circumstances Bob and the heirs would each have a wrongful death claim. While the wrongful death statute (Code of Civil Procedure Section 377.60) is a bit convoluted, it does provide that the heirs are wrongful death claimants if the decedent has no children or issue of deceased children.

Similarly, the legal heirs of Passenger No. 3, the exchange student with a legal guardian in Europe, would also have a wrongful death claim as long as Passenger No. 3 left no children or issue of deceased children.

The bottom line is that it is important to check into the background of each decedent and carefully read the wrongful death statute to ensure that all potential claimants are accounted for.

1. California Civil Code Section 1431.2(a)

2. California Civil Code Section 1431.2(b)

3. California Civil Code Section 1431.2

4. California Civil Code Section 1431

5. Ambriz v. Kress (1983) 148 Cal. App. 3d 963

6. Bob Parrett Construction, Inc. v. Superior Court (2006) 140 Cal. App. 4 th 1180.

7. Hackett v. John Crane (2002) 98 Cal. App. 4th 1233

8. Code of Civil Procedure Section 877.6.

9. Tech-Bilt, Inc. v. Woodward-Clyde & Associates (1985) 38 Cal. 3d 488.

10. Std. Pac. of San Diego v. A. A. Baxter Corp. (1986) 176 Cal. App. 3d 577

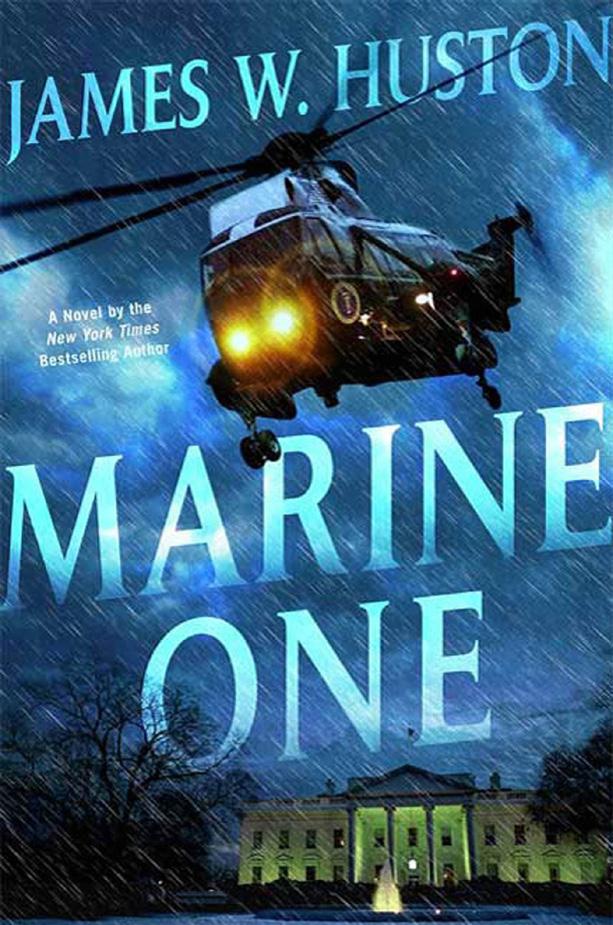

Two days before AIA Nashville, I was sitting around a campfire with a new acquaintance. Instead of rolling his eyes when I told him why I was going to Nashville, he told me that he just read a novel about an aviation lawyer. I asked him several questions designed to unearth his mistake – how could he have read a novel about an aviation lawyer if I was unaware such a thing existed? I quickly accepted my ignorance, ordered a copy from Amazon, and ripped threw it within a few days.

The book is a full novel published 13 years ago that describes the fatal crash of Marine One (the U.S. President’s helicopter) through the eyes of an aviation attorney. The scintillating cast includes a fairly active claims adjuster and her London principals, all sorts of experts, sketchy witnesses, several supporting lawyers, and an egotistical, media-hungry plaintiff’s attorney. Here’s how Amazon describes the novel:

The President rushes across the South Lawn through a pounding thunderstorm to Marine One to fly to Camp David late at night. His advisers plead with him not to fly, but he insists. He has arranged a meeting that only three people in his administration know about. After fighting its way through the brutal thunderstorm on the way to Camp David, Marine One crashes into a ravine in Maryland, killing all aboard. The government blames the European manufacturer of the helicopter and accuses them of killing the President. Senate investigations and Justice Department accusations multiply as Mike Nolan, a Marine Corps reserve helicopter pilot and trial attorney in civilian life, is hired to defend the company from the criminal investigations, then from a wrongful death lawsuit brought by the most notorious lawyer in America on behalf of the First Lady. Nolan knows that to prevail in the firestorm against his client, he has to find out what really caused Marine One to crash, and why the President threw caution aside to go to a meeting no one seems to know about. To clear his client, Nolan

must win the highest-profile trial of the last hundred years with very little working for him, and everything working against him.

Marine One expertly mixes political intrigue with courtroom drama and fast-paced action in the most exciting thriller of the year.

Of course, for those of us that handle plane crashes for a living, there are all sorts of literary liberties we could quibble about, but this little read contains many more instances of scenes, patterns, and discussions that feel very familiar. To check my biases I searched for other reviews and found them to be universally positive — using words like “gripping,” “outstanding,” and “couldn’t put it down.”

There isn’t much information about the author online, and unfortunately, James W. Huston passed away in 2016. However, what I could unearth about him from Wikipedia revealed that he certainly had the background to write a credible plane crash novel. His father was a decorated WWII veteran and history

professor. Huston was a U.S. Navy fighter pilot and Top Gun graduate before embarking on a legal career. He practiced with several law firms while continuing to fly in the Navy and Naval Intelligence Reserves, retiring as Commander in 1997.

Huston led the tort and product liability practice group of Gray Cary Ames & Frye in San Diego until 2004 when he joined Morrison & Foerster. Meanwhile, he published six novels prior to Marine One and two more subsequently.

I would recommend this book to pretty much anyone who enjoys reading “plane and peril,” but I strongly recommend it to anyone reading this in The Binder.

Alan L. Farkas is a partner with SmithAmundsen in Chicago and a member of the Eagle Society.

Marine one expertly mixes political intrigue with courtroom drama and fast-paced action in the most exciting thriller of the year.

As climate change and sustainability remain top of the agenda, the electrification of aircraft is much anticipated. While we’re a long way from seeing fully electric commercial aircraft, the technology is fast evolving…

Ever since Wilbur and Orville Wright made their first historic powered flight in 1903, the aviation industry has been a loyal user of hydrocarbons as a source of fuel. The simple matter is that hydrocarbons, be it petrol, diesel, or kerosene, offer a fuel that is plentiful and manageable. The impressive energy density of a hydrocarbon fuel allows aircraft to carry and extract the energy over huge distances such as that needed to fly a large passenger aircraft from Perth, Australia to London, United Kingdom without the need to refuel.

The advantages of hydrocarbons as a fuel source are numerous, however times are changing. Fossil fuels are finite and our continued reliance on them is simply unsustainable. Furthermore, the concerning and measurable impact on

the environment and predicted global temperature rises has created the urgent need to take a hard look at our 100 years plus reliance on the black stuff.

The aviation industry has had some notable electric milestones in recent years and has made enormous strides in finding an alternative to fossil fuels. You can now buy a 2-seat fully electric light aircraft that has an impressive 1-hour endurance with 30-minute reserve making it ideal for training schools. At the other end of the spectrum, the collaboration between UK firms Electroflight and Rolls-Royce has achieved a world record for the fastest all-electric aircraft recording an official speed of 387.4 mph, making it the fastest all electric vehicle on earth.

It is probably within the newly emerging sector of Urban Air Mobility (UAM) which involves low altitude urban ultra-short distance Vertical Take-Off & Landing (VTOL) flights where we will see the biggest shift towards electric power. This multi-

billion-dollar industry is growing fast and is well suited to the capabilities of current battery technologies on offer. Countries such as Norway — where the geography makes road journeys much longer than point to point distances — would greatly benefit from the offerings of Urban Air Mobility.

Commercial aviation has also been busy capitalising on the advantages of electric power albeit in a more subtle way. The major aircraft manufacturers have for a long time been focusing on methods of improving the fuel efficiency of their aircraft. New generation aircraft such as the Airbus A350 and Boeing 787 now use very little of the main engine’s mechanical power to run air conditioning, hydraulic and other systems. These systems are now powered by electric motors leaving the gas turbines to be optimized for providing thrust.

The sight of electric vehicles and charging stations on the public roads today is increasingly common, but the same

change cannot be easily observed with aviation. Here, we look at some of the main reasons why.

The first is a matter of weight: an electric car can be more than one ton heavier than its combustion engine equivalent. While this is not so much of an issue in a

road car, in an aircraft, weight reduction is a designer’s obsession. The lower the weight, the greater the range, efficiency and payload the aircraft can offer. The increased weight of even the most advanced batteries would make it a no-go for almost all aviation applications.

The second hurdle in aviation compared to the automotive sector is the increased time required to test and certify new technologies to enable them to be used commercially in public transport. It is a common belief that aviation is a cutting-edge sector and this — to a certain extent — is true, however, in an industry that is so regulated, change can take time to filter through.

There are a number of significant problems in producing and operating electric aircraft

that have any practical payload and range greater that the Urban Air Mobility offering. A kilogram of the most advanced fully charged battery still only holds a fraction of the usable energy that a kilogram of kerosene contains. This, coupled with the highly complex battery thermal managing systems required, results in a design problem that cannot be solved with current technology.

The time to charge an electric aircraft is also a significant issue. The high-pressure refuel systems at major airports can refuel hundreds of aircraft in short turn-around times every single day. It is a well-known fact that the national grid braces itself during every advert break of a major TV program due to the national synchronised flick of the kettle switch. Imagine the impact on the local electrical infrastructure of hundreds of aircraft on charge at a major airport like Heathrow.

The short term will certainly see further advances in the use of electrical technologies to help reduce the amount of hydrocarbon fuel used. It is likely to manifest in the form of continued hybridisation of aircraft. Systems such as galley power, cabin lighting and in-flight entertainment systems currently get their power from small electrical generators bolted to the aircraft’s main engines which increases their fuel burn. If the galley and cabin systems could be powered by their own battery systems that were charged during the aircraft turnaround, it would further reduce the demands on the

main engines and drive-up efficiency. Further ideas that may be a little further down the road in coming into wide use may include in-wheel motors that could allow the aircraft to taxi to and from the runway without the need for the main engines to be running — a major advantage for fuel efficiency and local environmental impact at the airports. Possibly the greatest form of hybridisation would be for the aircraft to use the conventional fuel for high-power activities such as take-off and climb but, once the aircraft was established in the cruise or descending, the engines could switch to electric drive — a bit like a flying hybrid car.

It seems we are in a waiting game for new storage and charging technologies to emerge that will enable us to really move on from fossil fuels. As one battery designer commented to me recently, we have simply run out of elements on the periodic table to use - what else is there after lithium?

Despite these challenges, electric power is clearly making an impact in aviation. The urban air mobility should help reduce the number of road journeys, and the work being done by the major aircraft manufacturers is bringing down the level of carbon dioxide per passenger seat kilometer with every new model released. However, a game-changing development in energy storage systems will be required to enable the realistic hope of ending our reliance on kerosene. Did anybody mention hydrogen…?

Emerging technologies will no doubt be expensive in their first iterations. Electric GA aircraft would still need to have shockload inspections for propeller strikes and the further reliance on battery systems could lead to more thermal runaway events with resulting damage to the aircraft.

One of the biggest changes to potential claims could be that of theft and off-aircraft damage to battery systems. The Urban Air Mobility model is being, in-part, built on the idea that a depleted battery can be removed from the aircraft by means of a quick disconnect system and a freshly charged battery slotted into place to enable quick turnarounds. The depleted battery would then be taken to a ground-based facility to be re-charged and ready for use. This practice, although entirely reasonable from an operational point of view, could lead to increased handling damages, multiple connection cycles and theft occurrences of these very expensive parts.

As technology evolves and parts become more complex, the cost of repairs as well as replacement will inevitably increase. As we saw with the industry’s adoption of composite materials in the last new generation of aircraft, the method of repair was completely changed. These

materials were, initially at least, unknown and complex to third party repair organisations — often with closely guarded intellectual property We saw manufacturers developing something of a monopoly over new material repairs, and notable impacts on the spares market — all of which ultimately impacted costs. Will we see the same trend playing out as electric technology is adopted

With electric powered aircraft still in its infancy, many aspects of mainstream adoption remain unknown. Continued dialogue between the loss adjusters, brokers and underwriters involved will be necessary to navigate this new terrain. Through this communication the full scale of the risks will be identified and, ultimately, effectively mitigated and managed. Such groundwork should steer us towards safe, swift and more sustainable flying in the future, the full benefits of which we are yet to realise.

Andrew Southall is a Senior Aviation Surveyor for McLarens Aviation, London. A licenced aircraft engineer and graduate from Kingston University with a First Class Honours Degree in Aerospace Engineering. Andrew’s aviation career spans over 30 years of industry experience in both commercial and general aviation sectors.

This article was first published in Insurance Day, 29 Apr 2022. Reprinted with permission.

Thank you to the more than 70 aviation insurance professionals who joined us in Atlanta, Georgia for the 2022 AIA Open on September 19. The blue skies and sunshine provided the perfect backdrop for the day of golf, networking, and fun on the course. Missed this year’s golf scramble? Mark your calendars for AIA’s next scramble Saturday, May 6 at the 2023 AIA Annual Conference in Tucson, Arizona. Registration will open in early 2023.

The 2022 AIA Open was made possible thanks to the generous support of our sponsors. Thank you also to our two volunteers, Amira Couch and Lesley Walker from USI Insurance Services, who arrived very early to help prepare the golfer gift bags and ensure registration ran smoothly.

In 2019 when Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 crashed — the second Boeing 737 Max 8 to do so — I remember clearly that I was at home about to leave for the office. I recall making the connection to the crash of the same aircraft type just a few months earlier and sensing immediately that there was a larger narrative here and that it wasn’t good. Fast forward to today and this loss is the biggest single event in aviation history.

Aside from the dramatic and devastating circumstances, what makes it astonishing from an underwriting perspective

is the sheer magnitude of the passenger settlements. It’s never comfortable putting a number on the value of a human life, but the amounts in this case certainly exceeded the industry’s expectations, ultimately triggering an upwards review

of many of our costing assumptions on passenger awards.

We are all very much aware of social inflation and the recent so-called ‘nuclear verdicts’ that the industry has witnessed in the United States, where disproportionately high awards have been granted in cases of death or injury. And while we do not expect this to be the case on every single loss, the frequency of runaway verdicts has clearly increased, and the trend appears to be here to stay. Evidence points to the aggressive behavior of the plaintiff bar in adopting various strategies to push awards, whether in or outside of court.

Limits in aviation continue to hold on a very high level. We see flying and even non-flying risks at times carrying USD 500 million to USD 1 billion of limit for

general aviation-type risks — even higher for airlines — and this is for any one risk.

Aviation is volatile by nature. We could be underwriting the best risk, which we know extremely well, with the best safety standards and top pilots. But the fact of the matter is that accidents occur, and when they do, our limits are increasingly fully exposed.

We have seen in the past years a couple of U.S. GA losses (flying and non-flying) where substantial awards were granted exposing limits in the hundreds of millions. This begs the question: how can this be sustainable in the long run? And perhaps more pressingly: how can re/insurers adequately price for this uncertainty?

It is fair to say that the market has reacted well in recent years in increasing premiums in light of the above, and we have seen important progress in the form of insurers moving more to coinsurance and reducing limits where possible. This trend must continue, with tighter control of exposures via line management and reduction in limits where possible, and the introduction of passenger stops, which is a good start.

Reinsurers also play a role here. Insurers are having to pay more for their protections to cater for this rise in severity. Reinsurance capacity, whilst still available, is more

selective. Our main product is the sale of a promise, a promise to pay when our clients need it most. However, the product that we sell, with the limits that we give, at times feels like US casualty – where consumers won’t think twice to face operators and large corporate risks in court.

So, how can we as an industry address the increasing frequency of runaway verdicts? Closer cooperation between the insurance industry and governments to raise awareness could be an important foundation for change. And there are options to consider on the underwriting side, such as introducing passenger stops on Industrial Aid and airline-type risks too, or perhaps introducing sublimits or aggregate limits on non-flying risks.

In the first place, however, we need to face the fact that if the trend of claims inflation is not broken, these risks will become exceptionally expensive. To prevent them from becoming uninsurable in future, the industry must recognize this danger now — and adapt quickly.

Raffaella Basile is Chief Underwriter Aviation with Swiss Reinsurance Company in Zurich, Switzerland. She is an aviation expert in both insurance and reinsurance whose career spans twenty-five years in various roles. Raffaella assumed the role of AIA Director of Reinsurance in 2022.

Many insurance professionals simply don’t know what a pilot looks for in selecting a flight school. Normally, they simply steer the pilot to a list of insurance company-approved training facilities. As the pilot shortage becomes critical, this approach will no longer be viable.

The pilot hiring binge has transformed the pilot/ employer relationship and insurance companies are caught in the middle. No longer is the aircraft owner able to dictate to the pilot when and where they can attend initial or recurrent training. No flight training organization is right for every pilot.

Every school has a niche, and most pilots gravitate to the school that meets their needs. Some pilots choose the big-name schools, while others look for a more personal training experience. Some

training facilities will accept any pilot, while others are highly selective. Some pilots want factory-approved, regimented training. For some pilots, quality of life issues trump being away from home for 20 days to qualify on a new piece of equipment.

Required training is becoming a negotiated benefit with the pilot applicant having more say in when, where, and what type of training they find acceptable. This results in the aircraft owner negotiating with the insurance company to get the pilot approved rather than restart the hiring process.

Safety is everyone’s primary goal, followed by reduced claims. In the flight training business, we see trends

before they become claims. The following is an unscientific look at the trends we are seeing in the flight training industry:

1. Skill Set – We are seeing a degradation of basic instrument skills. There is a big difference between the instrument flying abilities of the older professional pilots versus the average owner-operator pilot. Newer pilots are becoming more autopilotdependent and it is a training conundrum. As more aircraft manufacturers install autoland capabilities and automatic upset recovery systems, system management is becoming more important than basic IFR flying skills. Both skills must be incorporated into training.

2. Technology – The constant upgrade to available technology has created a knowledge void. Unfortunately, many pilots are unable to fully utilize the equipment installed in their aircraft. We see a definite training failure in the upgraded avionics segment. New avionics introductions and capabilities are expanding faster than simulators can be upgraded. This is leading to negative transfer of learning as pilots are being trained on obsolete equipment.

3. Safety Practices – Best practices can be individually taught but it takes the entire company to instill a safety mind set. Everyone from the CEO down to the person who cleans the hangars needs to be on board. But the single airplane, single pilot flight department usually doesn’t have an SMS program. In fact, we rarely see upper management involved in the training process at all. Less than 1% of corporate aircraft owners have inquired about their pilots’ abilities during training.

4. Attitude – Every pilot should approach training as if they still have something to learn. We look for a balance between two extremes. Unfortunately, to some pilots safety isn’t a big seller. If it wasn’t mandated by the FAA or insurance company, these pilots would not attend initial or recurrent training. On the other extreme are the pilots that look for any excuse not to fly.

Airplanes are safe staying in the hangar, but they aren’t designed to stay in hangars. They are designed to fly and if the pilot doesn’t fly regularly, attending training is a waste of time.

5. Currency – We are seeing pilots with more make and model time. This is probably due to the increasing useful life of updated airframes.

6. Age – The average age of our students is trending younger. We see companies hiring pilots who would have previously been considered unqualified. While many clients are no longer employing pilots over the age of 70, there’s been a large increase in the number of retired airline pilots who have become contract pilots.

The training industry is changing rapidly. New technology, drones, and the introduction of new aircraft coupled with a looming pilot shortage will make for a challenging decade. The one constant however, is still safety.

Doug Carmody is the owner of Executive Flight Training. He’s a retired airline captain and currently serves as a FAA examiner on the Citation 500, #510, #525 and 560XL.

The Wattles Fellowship was founded in 1969 with the original purpose of providing opportunities for women to work in the prestigious London insurance industry. Over the years, the job description has changed from being mostly clerical to the only program of its kind offering a one-year, fully-integrated position in the London insurance market.

The AIA Education Foundation has consistently supported the fellowship with two $2,500 grants for the aviation-specific fellows, assisting with the cost of relocating to and living in London for a year.

Each year, three women graduates from Vanderbilt University are selected to participate in the Wattles Fellowship. Following recent and successful efforts to attract a broader and more diverse group of applicants, more than a third of applications were submitted by racial/ ethically diverse individuals, with five countries represented.

This year’s Selection Committee was composed of 19 Fellows and two employer representatives: Alexis Faber, COO at Willis Towers Watson; and Phil Stafford, Executive Director at Arthur J. Gallagher.

(photo, left to right)

Mackenzie Moore

Bachelor of Science in Human and Organizational Development, Minor in Business

Bachelor of Science in Political Science, Minor in Business

Sarah Crosby

Bachelor of Science in Human and Organizational Development, Minor in Business

We wish them a valuable experience and hope to welcome them to the aviation insurance industry upon completion of the

The AIA Education Foundation was established in 2008 on behalf of the Aviation Insurance Association to raise funds for educational programs, grants and scholarships (awarded by the AIA Board of Directors) to aid, assist and encourage students or individuals to continue their interest in pursuing aviation insurance as a career. The Foundation is a 501c3 organization and needs your support to continue its work. Donations may be made via the AIA website at http://www.aiaweb.org.

President

Greg Sterling

AIG Aerospace Atlanta, GA greg.sterling@aig.com

Chris Morin

Murray, Morin & Herman, P.A. Tampa, FL cmorin@mmhlaw.com

Treasurer

Luke Uithoven

Kimmel Aviation Insurance Agency, Inc. Greenwood, MS luke@kimmelinsurance.com

Secretary Ian Wrigglesworth

Guy Carpenter London, United Kingdom ian.wrigglesworth@guycarp.com

Director, Agent/Broker Division

David Hampson

Schrager Hampson Aviation Insurance Agency LLC Bedford, MA david@planeinsurance.com

Director, Attorney Division

Mike McGrory

SmithAmundsen, LLC Chicago, IL mmcgrory@salawus.com

Director, Claims Division

David Gourgues

McLarens General Aviation Celebration, FL david.gourgues@mclarens.com

Director, Reinsurance Division

Raffaella Basile

Swiss Reinsurance Company Ltd Zurich, Switzerland

Raffaella_Basile@swissre.com

Director, Underwriter Division

Wes Collier

Old Republic Aerospace Kennesaw, GA wcollier@ORaero.com

Director-Elect, Underwriter Division

Jeffrey Sutton

London Aviation Underwriters, Inc. Federal Way, WA jtsutton@londonaviation.net

International Director

Andy Trundle

Starr Aviation London, United Kingdom Andy.Trundle@starrcompanies.com

Director-At-Large Nicole Wolfe Stout

Strawinski & Stout, P.C. Atlanta, GA nws@strawlaw.com

Director-At-Large

Chris Arnold

Sutton James an Optisure Risk Partner Hartford, CT carnold@suttonjames.com

International Director-At-Large David Watts

Old Republic Canada Ontario, Canada dwatts@orican.com

Mary Gratzer

Aviation Insurance Association Lexington, KY mary.gratzer@aiaweb.org

AIA – Aviation Insurance Association

AOPA – Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association

ASAP – Aviation Safety Action Program (FAA)

ASIAS - Aviation Safety Information Analysis and Sharing system (FAA)

CASA – Civil Aviation Safety Authority (Australia)

CAAC – Civil Aviation Administration of China

COPA – Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association

EAA – Experimental Aircraft Association

EASA – European Union Aviation Safety Agency

E6B – A type of manual or electronic flight computer

FAA – Federal Aviation Administration (U.S.)

FBO – Fixed base operator (service station for aircraft and pilots)

FDM/FOQA – Flight Data Monitoring/ Flight Operations Quality Assurance

GA – general aviation

GAMA – General Aviation Manufacturers Association

IATA – International Air Transport Association

IBAC – International Business Aviation Council

ICAO – International Civil Aviation Organization

IFR – Instrument flight rules

IMC – Instrument meteorological conditions

IS-BAO – International Standard for Business Aircraft Operations

IS-BAH – International Standard for Business Aircraft Handling

MRO – Maintenance Repair Organization

NBAA – National Business Aviation Association

NTSB – National Transportation Safety Board (U.S.)

P&C – property and casualty

SMS – Safety Management System

VFR – Visual flight rules

WAI – Women in Aviation International

This is an abridged list of aviation insurance terms that appear in current and previous editions of the AIA’s Binder magazine.