CHAIR

Lt Gen C.D. Moore II, USAF (Ret)

VICE CHAIR

My name is Rorie Cartier and I’d like to introduce myself to you as the new CEO of the Air Force Museum Foundation. I am very excited to be leading such an important professional association, with a strong and impactful mission. Of the many factors that drew me here, perhaps the most affecting was the organization’s strongly rooted values and forward-thinking culture. I saw a team of innovators here who are building a vision for the Foundation and the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force™ together — striving for excellence, fi nding creative ways to do more, and confi dent that the history and heritage of the Air Force is preserved and disseminated through exceptional exhibits and programs designed to educate and inspire.

I’ve been working in the nonprofi t and museum profession for over 10 years starting as a volunteer. Over the years, I have had the opportunity to talk with many veterans, members, partners, directors, employees, and other stakeholders, and our conversations have increased my enthusiasm for the museum and nonprofi t profession and the value it brings to visitors and supporters from all over the world.

I look forward to building upon the successful collaboration between the Foundation and the Museum to make the Air Force’s legacy and heritage accessible and meaningful to new generations. If you have never visited the Museum (or have not visited in a while), please come by and let me know you are here; it would be a special pleasure to personally welcome you if I am available. If you cannot visit in the near future, I encourage you to engage with the Foundation and the Museum online or through social media (social profiles below) to learn about everything that is happening and how you can play an important role.

CMSAF Gerald R. Murray, USAF (Ret)

SECRETARY

Gen Lester L. Lyles, USAF (Ret)

TREASURER

Mr. Scott E. Lundy

Lt Col Angela L. Billings, USAF (Ret)

Col James F. Blackman, USAF (Ret) Mr. John G. Brauneis

Brig Gen Paul R. Cooper, USAF (Ret) Ms. Linda Y. Cureton

Dr. Pamela A. Drew

Mr. Roger D. Duke Ms. Anita Emoff

Col Frederick D. Gregory Sr., USAF (Ret) Mr. Benjamin T. Guthrie

Mr. James L. Jennings

Mr. Scott L. Jones

Lt Col Ki Ho Kang, USAFR (Ret) Dr. Thomas J. Lasley II

Maj Gen Ted Maxwell, USAF (Ret)

Maj Gen Brian C. Newby, USAF (Ret) Gen Gary L. North, USAF (Ret) Mr. Edgar M. Purvis Jr.

Maj Gen Frederick F. Roggero, USAF (Ret)

Maj Gen Mike Skinner, USAF (Ret)

CMSgt Darla J. Torres, USAF (Ret)

Mr. Randy Tymofichuk

Col Mark N. Brown, USAF (Ret)

Mr. James F. Dicke II

Ms. Frances A. Duntz

Mr. Charles J. Faruki

Maj Gen E. Ann Harrell, USAF (Ret)

Col William S. Harrell, USAF (Ret)

Mr. Jon G. Hazelton

Rorie Cartier, PhD Air Force Museum Foundation Chief Executive OfficerMr. Charles F. Kettering III

Mr. Patrick L. McGohan

Lt Gen Richard V. Reynolds, USAF (Ret)

Col Susan E. Richardson, USAF (Ret)

Gen Charles T. (Tony) Robertson, USAF (Ret)

Mr. R. Daniel Sadlier

Col James B. Schepley, USAF (Ret)

Mr. Scott J. Seymour

Mr. Philip L. Soucy

Mr. Harry W. (Wes) Stowers Jr. Mr. Robert J. Suttman II, CFA

Medal of Honor recipient: 2nd Lt Robert E. Femoyer

Updates on Curtis JN-4D Jenny, McDonnell Douglas F-15A Streak Eagle, Douglas A-1H Skyraider, and Convair SM 65 Atlas 9 (MA-9) 52 |

Museum’s rocketry team advances to the national fi nals, volunteer awards, new exhibits, and exciting events; plus Open Aircraft Days and Plane Talks.

On the Cover: The F-15A Streak Eagle in the Restoration hangar at the National Musuem of the U.S. Air Force — see story on page 32.

U.S. Air Force Photo/Ken LaRock

10

”In the thick clouds we were in, the margin of error was very small.”

18 | FIRST STRATEGIC BOMBING OF THE UNITED STATES

“The Army did not want to create hysteria among the American civilian population in the Pacific Northwest.”

24 | VOODOO RESCUE

“He took to painting a Voodoo silhouette above the crew entry door of his RB-57A for each successful ‘rescue.’”

“Nothing gets your attention like a klaxon going off at 0200.”

44

“Telemetry intercepted during the first minute of a launch was the most important to the analysts.”

48

“I saw a stream of fire from his bird and as it headed to the ground another stream came back at him.” 34-38

Don’t miss these specials from the Museum Store. A perfect way to wrap up your holiday shopping!

DISCLAIMER: The views and opinions expressed in the Friends Journal articles and Feedback letters are solely those of the authors in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of the Air Force Museum Foundation, Inc., the United States Air Force or any other entity or agency of the U.S. Government. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

It has been a busy year here at the National Museum of the United States Air Force™. New exhibits have been researched, curated, constructed, and either put on display or are in the process of being deployed. There have also been special exhibits — a number have come and gone, the National Museum of the Marine Corps Art Exhibit and the Above and Beyond flight exhibit are on display until mid-December, and more are planned for next year. Restoration continues their never-ending work, with roughly a dozen projects large and small ongoing, and there are exciting projects on the horizon. The World War I Dawn Patrol Rendezvous took place last month. And September marked the 75th anniversary of the United States Air Force.

As the year of celebrations winds down, we barely have time to catch our breath before marking another milestone here in Dayton. Next year, 2023, the National Museum of the United States Air Force celebrates 100 years ! There are events planned throughout the year, so be on the lookout for information, dates, and times as plans are fi nalized. We hope you’ll be able to join us to help the Museum celebrate — after all, it’s donors like you who have made the Museum the largest military aviation museum in the world.

I was pleasantly surprised at the amount of feedback we received on stories in the summer issue. In particular, the Igloo White story elicited responses from a number of veterans who had fl own missions in support of that operation. Their input adds another dimension to the story told by Steve Umland. I am grateful that readers are eager to share and fill in the broader picture.

Please consider sharing your own stories of service. See my request on page 43 for specifi c themes I am interested in. However, my requests are not exclusive — I am interested in any stories of service in any capacity in the Air Force or its predecessor services. I hope you will consider sharing yours.

Enjoy!

Alan Armitage aarmitage@afmuseum.com

CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER

Rorie Cartier, PhD

CHIEF DEVELOPMENT OFFICER

Christopher Adkins-Lamb

DIRECTOR, FOOD SERVICE AND FACILITIES

Gary Beisner

DIRECTOR, EVENTS Mary Bruggeman

DIRECTOR, ATTRACTIONS William Horner

DIRECTOR, RETAIL Melinda Lawrence

ACTING DIRECTOR, MARKETING AND COMMUNICATION

Cheryl Prichard

DIRECTOR, HUMAN RESOURCES Sarah Shatzkin

DIRECTOR, FINANCE AND ACCOUNTING Crystal Van Hoose

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE U.S. AIR FORCE™ DIRECTOR David Tillotson III

FRIENDS JOURNAL EDITOR

Alan Armitage

CREATIVE MANAGER Cheryl Prichard

If your Friends Journal is damaged during delivery, you have a question about delivery, or you have a change of address or other information, please contact the FRIENDS OFFICE: 937.258.1225 friends@afmuseum.com

The Friends Journal is published quarterly by the Air Force Museum Foundation, Inc., a Section 501(c)(3) private, non-profit organization dedicated to the expansion and improvement of the National Museum of the U.S. Air ForceTM and to the preservation of the history of the United States Air Force. The Air Force Museum Foundation, Inc. is not part of the Department of Defense or any of its components and it has no government status. Printed in the USA.

USPS Standard A rate postage paid at Dayton, OH. The Friends Journal is mailed on a quarterly basis to donors to the Air Force Museum Foundation.

We received quite a bit of feedback on the stories in our Summer issue…

We owe the author of this story an apology — we listed him as Don, when he should have been listed correctly as Maj Delmar Pullins, USAF (Ret).

We also received a correction to wording in that same story. Capt Larry Robinson noted that the Genie (AIR-2) was a rocket, not a missile. “It’s the only question I missed at Block 8 in Munitions Officer School,” he added. Thank you for the note, Larry. We apologize for the error but are glad to know we were in good company.

“In the Summer 2022 Journal, there is a picture of the YB-17 on page 41. There are no visible insignia or other easy identifier, but the propeller blades look like they are set to turn clockwise when viewed from the front (as in the picture). That is the opposite direction from how they actually turned. Was that picture printed backwards?” Good catch, Gary. The photo was inadvertently fl ipped during production.

Several readers wrote to share that they had used the Dzus tool in the Collection Connection piece on page 50.

“On page 15, in the piece by Don Boldt, a reference about the Snark missile reminded me of a story from my days at the Cape during Mace B launch crew training. Our launch pads 21 and 22 were close to the Snark launch pads and I recall the difficulty in launching the Snark — as the article stated, the intercontinental cruise missile was so big it required two solid rocket boosters, one on each side for launch, which had to ignite at precisely the same instant and with identical thrust or the missile would pinwheel — which happened numerous times, causing the missiles to crash offshore into the water. The area became known as ‘Snark infested waters.’”

“We used these tools a lot on the F-15’s. I can’t recall the F-105’s or F-4’s using them. Later, working on B-1B’s and F-16C/D’s, I never saw one since they didn’t use the type fasteners. We called them “Snoopy tools.” Perhaps you can see why. I never heard of Dzus tool until I saw your picture.”

“Some people still used these in the early 1970s, when I was in aircraft maintenance. F-4 guys called it a “Snoopy” because it looked like Charlie Brown’s dog.”

The article about Operation Igloo White, by Steve Umland, garnered more feedback than any article we have published in recent years. The comments were from participants whose involvement covered a range of roles in the operation.

“In early 1968 I was assigned to fly the A-1E with the 1st Air Commando Squadron out of Pleiku AB in South Vietnam. Prior to my arrival the squadron moved to Nakhon Phanom AB (NKP) in Thailand. Upon my arrival I learned that our primary mission was putting mines in Laos and escorting the helicopters that were placing the sensors in the areas of the mines.

These missions were almost all over the Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and were fl own by A-1E aircraft and helicopters. The initial pilots in the squadron were almost all seasoned pilots and fl ying in their 2nd or 3rd war. The younger pilots in the squadron (I was one) listened and learned from the old heads.

“The squadron had developed a unique method to put the mines in place. They called it a “Swoop”, (which I will explain later). A mission involved 4 mine layers, two escorts, and a forward air controller (FAC). The mine layers had 6 tubs of mines each. The escorts were A-1E’s armed to suppress any ground fire the mine layers and helicopters should encounter.

At the briefi ng the FAC was requested to put in a marker where he wanted the mines to start. Then he would just send a marker down range in the direction he wanted the mines to be laid. In the meantime, the Hobo flight of layer aircraft would be between 8,000 and 10,000 feet. As the marker went in Lead would call for Hobo flight, “Go trail, push them up and set them up.” Immediately, Lead would roll in to a vertical dive pointed at the starting marker. Numbers

two, three, and four, and the two escorts would follow. This was where the name “Swoop” came about. Lead and those following would level out on the treetops at about 310 knots [about 357 mph]. As soon as our aircraft was level and pointed in the direction the mines were to be laid, we would press the fire button and empty all our mines in the direction we wanted them to go. Each aircraft would be straight and level for approximately 10 seconds. Then our tubs would be empty and we would pull off target and watch our airspeed drop from 250 to approximately 150 knots [288 to 173 mph]. At this point all of us were jinking to avoid any ground fire. The next thing we would do was check the box between the seats to see if any lights were on. If any were it meant that “tub” had not emptied and had to be jettisoned. We then looked each other over as we climbed out to make sure there was no battle damage. In the meantime, the escorts would join the FAC and go looking for targets. The maneuver resulting in the vertical dive to put in the mines had been labeled by the squadron as the “Swoop.”

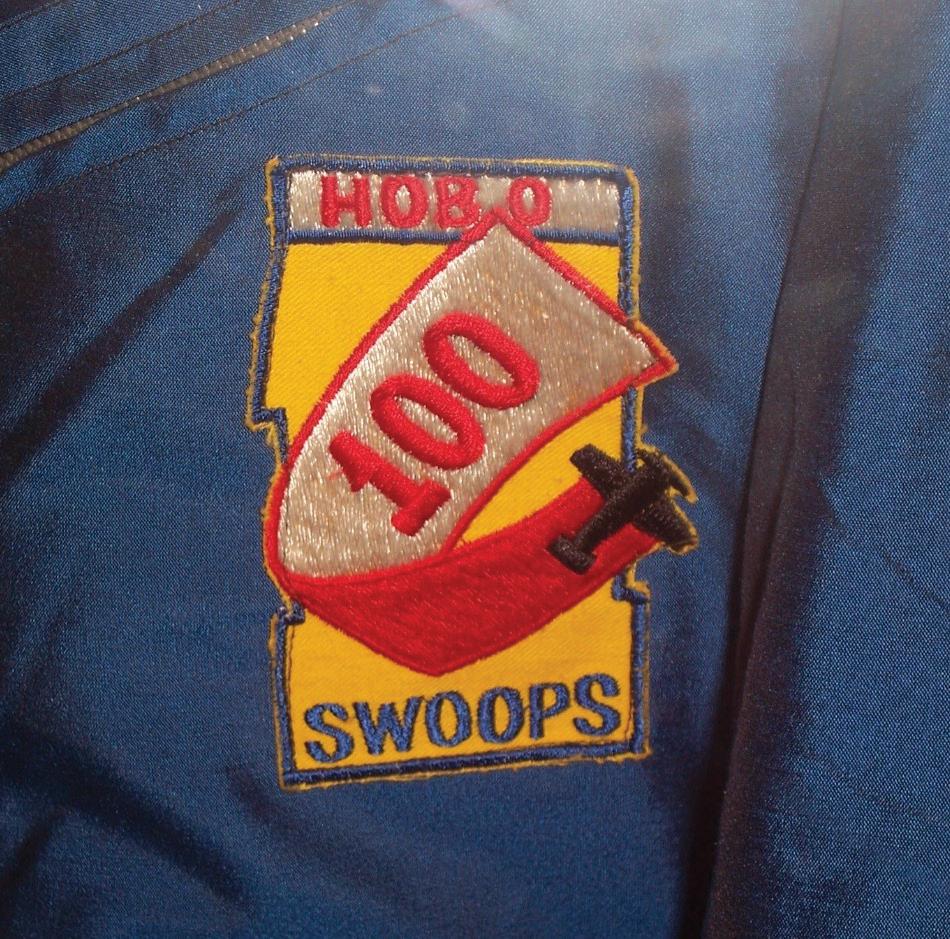

“Later as a tongue in cheek look at the 100-mission patches that were awarded to those who survived 100 missions over North Vietnam the squadron designed a 100-swoop patch. It was awarded to any pilot who survived 100 swoops in the 1st SOS. Of course, none of those were over North Vietnam.

“While I was there, we only lost 3 aircraft putting in mines. One was to ground fire, and that pilot violated the rule never to attempt mine laying under a cloud deck lower than 5,000 feet. The other two were

lost when lead turned off of the run between two karsts and was unable to clear the top. One and two collided with the ground with the loss of two aircraft and two men.

“The mines we put in were one of two types. One was shaped like a piece of pie and was about that size. The other was the size of a postage stamp and served as a noise maker. The larger one would take off a tire on a truck and in both cases the noise created was to be transmitted by the sensors so a strike could be sent in on the location of the noise. Although this was done immediately the reaction of a strike mission took too long to be dispatched. Thus, the mine laying and the sensors were not as effective as they could have been.

“We never learned the number of mines put in on a four-plane swoop. They were contained in seven tubes within each tub. Each aircraft carried six tubs. Thus, four aircraft would empty 24 tubs on each swoop. The main safety factor for the pilot was the mines were packed in Freon and did not become active until they dried out. Thus, if your control panel indicated that a particular tub had not emptied it was necessary that you jettison that tub as it could blow up on its own. We continued putting these mines and sensors in until late 1968.

“Some ideas work out well, and other times it is just an effort. I was personally never informed of a success with this system.”

MAJ GEN GARY L. CURTIN, USAF (RET), WROTE:“I enjoyed the Igloo White article in your Summer 2022 edition of Friends Journal. Steven Umland provided an excellent description of the Task Force Alpha/Igloo White operation. However, I want to point out one minor error in his discussion of the evolution of airborne monitoring of the sensors planted on the trail.

“He correctly indicates that the sensors were originally monitored by EC-121 aircraft, which were replaced by QU-22 aircraft. Then he indicates that the monitoring mission was taken over by C-130s flying out of NKP. In fact, the C-130s were part of the 7th Airborne Command and Control Squadron at Udorn RTAFB. The 7th ACCS provided airborne command and control of strike operations along the Ho Chi Minh Trail and also for CIA-sponsored ground operations by Laotian forces in northern Laos. The EC-130E aircraft carried a trailer-like capsule containing the airborne battlestaff and their radio gear. Each mission was 12 hours on orbit over northern Laos or over southern Laos. The day orbit over northern Laos was given callsign ‘Cricket’ and the night orbit was ‘Alley Cat’. The corresponding southern Laos orbits were ‘Hillsboro’ and ‘Moonbeam.’

“In November 1971, a fifth C-130 orbit was added to monitor the Igloo White sensors. Equipment was placed in some additional C-130s that joined the 7th ACCS, although no battlestaff crews were used. Everything was automatically collected and relayed to NKP. The fifth orbit mission had the callsign of ‘Trump.’

“As squadron intelligence officer, I flew on all the orbits, except Trump. The history of the 7th ACCS is one of the USAF’s untold stories, although the mission continued from the Vietnam War through numerous other military operations in Southwest Asia, Europe, and elsewhere. It’s ABCCC mission was finally disbanded in 1991 and the unit designation transferred to the Looking Glass mission flown out of Offutt AFB in Omaha, Nebraska.”

We appreciate all the feedback and insight into the flying side of the operation and know that the minor errors will be excused as slips due to the passage of time.

“I would like to comment on Steven Umland’s article, ‘Operation Igloo White,’ in the Summer 2022 issue of the Friends Journal. He did an excellent job talking about Task Force Alpha and the overall program.

“There was a second part of the program that took place at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, just down the road apiece from NKP. The 25th Tactical Fighter Squadron, Assam’s Dragons, had the task of delivering the sensors that made up the strings along the routes in Laos. The individual sensors were loaded in a modified flare dispenser. It was a dangerous mission as it required a low-level, straight-line delivery. Near the end of my tour with the 433rd TFS, the 25th lost two aircraft in two weeks. On Feb 3, 1971, Lt Col Standerwick (KIA) and Major Norbert Gotner (POW) were shot down

while laying a string. During the rescue attempt, on two days in a row, one of my flights was diverted to assist the SAR. A little over a week later, on Feb 16, another aircraft was lost, but the crew was recovered safely.

“The 433rd, Satan’s Angles, played a role in Igloo White. Early in my tour at Ubon, the squadron selected me to be the teacher on using the LORAN bombing and navigation system installed in most of the 25th squadron aircraft. Before I could teach, I had to learn the system. I received a lot of help from (then) Major Bob Benbow and (then) Capt Roger Johnston. I also spent a lot of time in the LORAN maintenance hangar practicing with the system. All went well, and soon a number of our crews were using the LORAN for night bombing missions, and daytime pathfinder missions. The problem with the original LORAN system was maintaining a lockon. Flying near another aircraft, i.e. the tanker, or executing maneuvers over 15 degrees of pitch or bank would cause the ‘Settling’ light to illuminate indicating the system was not locked on and could not be used for accurate bombing. Sometimes it took 5-10 minutes to reestablish a lockon. Still, we were able to work around the problem and use it successfully.

“Again, with help from the 25th squadron, I was taught to fly LORAN ‘Flasher’ missions that had us directly in contact with TFA, call sign Copperhead. These were by far the most time demanding missions flown out of Ubon. The aircraft were loaded with 9 cans of CBU24 cluster bombs with radar activated fuses, and the aircraft were modified to use a longer duration intervalometer to increase the time between individual releases to about a half second separation. This mod allowed the weapons to be spaced along a longer section of target road. All the missions were flown at night because that was the time the trucks were moving and being detected by the sensors.

“Basically, this is how the whole thing worked: a convoy of vehicles or just people was detected along a string, and the data was transmitted to an orbiting aircraft, either manned or unmanned depending on the threat level in the target area. The aircraft would relay the data to TFA, and the operators would use travel speed and location to predict where the convoy would be in 15-20 minutes. We always flew single ship and were established in a racetrack holding pattern over central Laos. You could pick your own altitude, but I liked 10,000 AGL [above ground level]. Copperhead would come up on frequency with traffic information. It was broadcast as a coded 5-digit alpha numeric message. Using a simple decoder wheel (secret) it would provide a 5-digit message. The first three digits indicated the preplanned IP and Target, while the last two digits indicated the time in minutes after the hour for the Time over Target (TOT). We opened a book of some 20-25 preplanned missions, found the one with the matching code, and entered the IP and target information into the LORAN system. With little time to work and limited to shallow banked (slow) turns we had to commit to Copperhead that we were able to make

the time, or that it would be impossible to get there given where we were at the time. Once committed to a live run, we could control airspeed to adjust TOT. We got very good at it. Once on the final approach to the release point, Copperhead could adjust the release point based on changes in target speed. In the last minute or so before release, Copperhead could confirm release short or long by some distance to make a final correction. A short release was easy as we could select release advance with our bombing system. For a long release we relied on manual backup using the ‘One potato, two potato’ adjustment to WAG the release point.

“To sum this up, the sensor located, the signal was data linked, the computers and operators at TFA did their thing. The target info was radioed to the bombing aircraft, the WSO entered the info into the LORAN computer, and the crew navigated to the target and destroyed it.

“Most nights there was enough cloud cover below us to just be able to see the sparkle of the bomblets exploding. Occasionally there would be a larger flash, a secondary explosion, or many secondaries. On a clear night it was very satisfying to see the first doughnut (when the bomblets dispersed from the opened canister, they spread out to form a doughnut pattern with few to no bomblets in the center hole). The subsequent weapons filled in the holes from the previous ones, so the result was a ¼ mile wide by about 2 miles long impact area on the ground. With only one set of bombs per aircraft, once the run was complete it was time to head home. On most nights Copperhead would provide us with an observed bomb damage assessment on the way home. Some were like ‘five secondaries heard; no movement detected after attack’ others were simply RNO (Results Not Observed). During my year at Ubon (April 1970 to April 1971), I must have flown 25 Flasher missions. We did more than just find the target; we worked hard to kill it.”

“I enjoyed reading Steven Umland’s “Operation Igloo White, 1969-1970” in the Summer 2022 edition of Friends Journal. As one who planted those seismic and acoustic sensors via F-4D’s, it was interesting to learn more of what was being done at NKP to analyze the data they generated. I would like to clarify a couple of points raised by the author, however. First, the F-4D’s used to deliver the sensors along the Ho Chi Minh Trail belonged to the 25 Tactical Fighter Squadron at Ubon, Thailand — not Udorn. The 25 TFS became the dedicated Igloo White squadron sometime in late 1967 while still based at Eglin AFB, Florida. The entire unit deployed in late May 1968 and became part of the 8 Tactical Fighter Wing at Ubon.

“The second point regards the classification level of Igloo White. As best as I recall, there was little at the squadron level that was considered Top Secret. Secret, perhaps, but not Top Secret. What looked like a “bomb,” for example, was simply a shaped cannister to carry four acoustic sensors. The seismic sensors, or ADSIDs, [Editor’s Note: Air Delivered Seismic Intrusion Detector] were carried openly on the underwing ejector racks. I’m sure that Mr. Umland’s work at Task Force Alpha, along with the work being done by the intelligence analysts was classified at the TS level.

“All in all, Steven Umland has given us a most interesting and informative insight as to what went on at Nakhon Phanom, Thailand, as part of Operation Igloo White.”

Philip Handleman wrote to correct an error concerning the date of issue in the write up about the stamp in our last issue. “The 1957 stamp marked the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Army order creating the Aeronautical Division of the Signal Corps. That was on August 1, 1907, which explains the stamp’s issuance on August 1, 1957.” The error was mine — at the time I was also researching this issue’s stamp and crossed my facts. Thanks for the correction, and thanks for making this issue’s stamp possible.

The stamp in this issue is a 1997 32cent stamp “commemorates the 50th anniversary of the establishment in 1947 of the U.S. Air Force as a separate service from the Army,” according to the Postal Bulleting. The stamp was based on a photograph taken by Philip Handleman, featuring four U.S. Air Force Thunderbird aerial demonstration planes in fl ight, in a classic diamond formation. The stamp “was issued on September 18, 1997, in the courtyard of the Pentagon,” Handleman explained. “That day was chosen because it corresponded to the day in 1947 when Stuart Symington took the oath of office as the first Secretary of the Air Force (which is commonly considered the beginning date of the Air Force as a separate military service). The 1997 stamp is distinguished from the 1957 stamp by being said to honor the anniversary of the Department of the Air Force (with its roots stretching back to 1947) as opposed to the U.S. Air Force (with its roots stretching back to 1907).” Thank you for the background, Philip, and for the wonderful photo and stamp.

Send your comments to P.O. Box 1903, WPAFB, OH 45433 or email aarmitage@afmuseum.com For comments or questions directed at the Foundation that don’t pertain to the magazine, please visit the ‘Contact Us’ page at afmuseum.com.

facebook.com/ AirForceMuseumFoundation

@AFMFoundation #airforcemuseumfoundation

Tuy Hoa Air Base, Republic of South Vietnam, September 1968. The night was warm, sultry. “Your mission tonight will be a skyspot,” the intel officer said by way of opening the flight briefing.

Combat Skyspot was a weapons delivery method that relied on an MSQ-77 radar to direct the attacking aircraft to a weapons release point in the sky. The release point was offset from the target by the calculated ballistic trajectory of the weapons. In practice the method was similar to a ground radar-controlled landing approach. Combat Skyspot was implemented in Vietnam in 1966 to improve night and all-weather weapons delivery accuracy.

The intel offi cer continued, “Your target is an NVA [North Vietnamese Army] supply depot just south of the DMZ [DeMilitarized Zone, the border between North and South Vietnam]. Frag’d TOT [Time over Target] is zero one thirty hours [1:30 a.m.]. Contact skyspot on 267.8. Are there any questions?”

“Frag’d” referred to a portion or fragment of the daily Air Tasking Order sent out by 7th Air Force Headquarters. It specified and authorized all strike missions in

the Southeast Asia (SEA) theater of operations. In our case, we were designated a fl ight of two North American F-100D Super Sabres from the 31st Tactical Fighter Wing, call sign Sabre Four One. Our weapons load was four Mk 117 general purpose bombs each. We were directed to operate under Skyspot control for the strike portion of the mission.

Flight lead asked, “Any threats?”

“There are no known threats at the altitude you will run in at,” the intel offi cer replied. “There is a report of a 23 mm battery near Khe San, but you should be well above its effective altitude. Anything else?”

The flight leader looked at me. He was a senior captain, highly experienced with over 2,000 hours in the F-100. He had spent two tours in Europe before coming to Vietnam and was now approaching the end of his one-year tour here. I’d flown with him on numerous missions and had total confi dence in his airmanship.

I was the wingman on this mission. I was still a first lieutenant, straight out of F-100 training at Luke Air Force Base, Arizona. Vietnam was my first operational assignment. At this point, I was four months into my SEA assignment. I now had over 170 combat flying hours, but only about 300 hours overall in the F-100.

I shook my head.

The intel officer looked quizzically at us for a moment. “If there are no more questions, have a good mission,” he said.

Next, was the weather briefi ng.

“Currently, Tuy Hoa is 1,200 [foot cloud ceiling] overcast in light rain,” the briefer began. “Temperature is 73 degrees, wind from the southeast at 8 knots.” (One knot equals 1.15 miles per hour.) He paused, consulting his weather map, and then continued, “There is a frontal boundary lying just north of Quang Ngai with stratus clouds between 10,000 and 30,000 feet. You can expect imbedded thunderstorms from the vicinity of Da Nang to the DMZ with tops up to 35,000.”

Again, he paused, and looked at us for questions. When there were none, he continued, “Weather here at Tuy when you return is forecast to be 1,000 foot overcast, clear underneath with seven miles visibility. Clouds will be layered up to 20,000 to 25,000 feet. Winds remain southeast at 10 knots. Are there any questions?”

Again, flight lead looked at me. “None for me “I said.

“No questions,” Lead said to the weather briefer, “thank you.”

Turning to me, Lead said. “Looks like a routine Skyspot mission tonight.”

Looking at the briefi ng guide, Lead ran his finger down the items quickly and said to me. “All the briefi ng items are squadron standard. Take 10 second spacing on takeoff. It will be a right turn after takeoff to head up the coast. I’ll stay under the weather at 300 knots [345 mph] until you come aboard. Questions?”

“Nope, no questions,” I said, “Like you said, just routine.”

As we started to rise from the briefi ng table, Lead said, “Suggest

you set up your comm and weapons panels before taxi. Weather might be a little dicey up there.”

I nodded. Good idea, I thought.

Lead looked at his watch. “Its 11:45 p.m. now” he said. “Let’s check in at 12:20 a.m. for a 12:30 takeoff.”

Twenty-fi ve minutes later, preflight done, I climbed into the cockpit and strapped in. The F-100 cockpit was small and purposeful. No frills here. The control stick between my legs and the throttle by my left thigh fell readily to hand. The cockpit was dominated by the central instrument panel in front of my knees. The panel was filled with nearly 30 gauges and dials arranged like everyday coffee cups in a kitchen cabinet — the most used ones were in the center, up front. The rest seemed to be just where they fi t. The critical fl ight instruments, airspeed, altitude, heading and attitude indicator, were centered just below eye level. Various switches and controls for less frequently used equipment were arrayed alongside consoles by my left and right thighs. The radio and weapons controls were on the left console just behind and outboard of the throttle. Like a cluttered offi ce desk, with familiarity, everything was readily accessible when needed.

A few minutes later, with the engine started and cockpit checks complete, I waited for Lead’s checkin call.

The radio crackled. “Saber Four One check” Lead called.

“Two’s on,” I replied.

“Tuy Hoa Ground, Saber Four One taxi two takeoff” Lead said.

“Roger, Four One, taxi runway two one, altimeter 29.96, wind one fi ve zero at four” Ground Control responded.

Ten minutes later we were through Last Chance and Arming, the fi nal safety inspection and removal of weapons safety pins at the end of the runway. The rain had given way to a mist, and the cloud bases were clearly visible in the refl ected light from the Last Chance apron and perimeter lighting. The air was warm and close.

Lead’s canopy closed and I gave a thumbs-up sign as my canopy came down. He responded with three fingers held up indicating radio change to channel three.

Moments later. “Four One check.”

“Two,” I replied.

Then, “Tower, Saber Four One, ready for takeoff,” Lead said.

“Roger,” the tower replied “cleared for takeoff. Wind one fi ve zero at six. Contact departure control on 234.8.”

As he advanced power to taxi onto the runway, Lead held up four fi ngers for channel four, the radio preset for departure control.

“Check,” Lead called.

“Two,” I replied.

Lead taxied onto the far half of the runway, leaving room for me to take formation position on the near half. I made a quick glance as I took position on Lead’s left wing, and Lead twirled his left fi nger indicating engine run-up. I pushed the throttle full forward to MIL power and pressed hard on the brakes. (MIL, or military, power is 100 percent power without using afterburner.) The airplane surged against the brakes, the nose strut compressing slightly under the powerful thrust from the engine. I watched the engine instruments

settle to their normal full power setting, and then gave a thumbsup to Lead. He immediately gave an exaggerated head nod and released brakes. I punched the second hand on the clock and watched Lead’s afterburner light and then recede rapidly into the distance.

Ten ticks of the clock later, I released brakes and pushed the throttle outboard to light the afterburner. The bump from the suddenly increased thrust was reassuring, but with over 39,000 lb. for the engine to push, the acceleration, while smooth, was hardly exhilarating. Takeoff roll at this weight was typically over 8,000 feet. Just past the 3,000-foot-remaining marker, I pulled back on the control stick to rotate the airplane to takeoff attitude. I felt the bump as the main tires rolled over the departure end barrier cable, 1,500 feet from the end of the runway. Normal takeoff I mused, and moments later I was airborne.

My attention now shifted to Lead as I raised the landing gear and flaps. As the airspeed increased, I banked hard to cut off Lead who was now in a 30-degree banked right hand turn just under the cloud bases.

“Departure, Saber Four One airborne in a right turn.” Lead called.

Departure control responded with the standard “Roger, continue turn to three five zero, climb to 10,000 at your discretion.”

To join up with Lead, I pointed my airplane ahead of his such that he appeared about 45 degrees off my nose, in front of my left wing. This established the rejoin angle so that the airplanes converged to a single point in space. Then it was a matter of judging the cutoff angle and rate of closure to get to the rejoin point as quickly as possible without overshooting. I liked this part of flying, the fine judgment and delicate control to precisely manage the rate of closure. A minute or so later I slid

into position, three feet from Lead’s right wingtip.

I keyed the mike and said, “Two’s in.” I was pleased with myself for the expeditious rejoin.

Lead glanced over and smoothly increased power to just below full MIL. That gave me a little excess power to play with to stay on Lead’s wing. As our airspeed approached 400 knots (460 mph) we started a climb into the clouds. The clouds thickened around us, and I focused intently on the green navigation light on Lead’s wingtip.

For the wingman, things are never static in formation flying. Ripples in the surrounding air cause the two airplanes to move independently which changes the relative motion between the two aircraft. This must be corrected, or the wingman could collide with the lead or, in weather, lose sight of the lead entirely. Like all fighters, the F-100 was highly responsive to control inputs. To maintain position, precise, usually very small, adjustments of the stick and throttle were continually required — large enough to control the disturbance, but never too large or too late. In the thick clouds we were in, the margin of error was very small. I concentrated on keeping Lead’s green wingtip light in a small area on the left side of my canopy. Little did I know that light was going to become my only link to the “real” world.

After a few minutes, Departure Control said “Saber Four One, continue climb and maintain flight level two zero zero, contact Peacock on 236.6.

“Roger, Saber, channel 6, go” Lead replied.

Peacock was the air traffic control center (ATCC) for the northern half of South Vietnam. Unlike an ATCC in the States that dictated flight paths and altitudes, Peacock functioned more as a flight following and coordinating agency. In Vietnam, the pilots determined where to go and at what altitude.

After checking in with Peacock, we continued our climb. We were in and out of clouds and reflections from Lead’s blinking navigation lights became distracting. Lead’s white navigation lights just behind the cockpit and on the top of the tail were out, and so I had no sense of depth when we were in the thicker clouds and Lead’s fuselage was obscured. It was like watching a singular green light in a gray fog.

Presently, I keyed my mike and said, “Lead, go dim steady and turn on your formation lights.” Formation lights were spotlights embedded in the upper wing surface and oriented to shine on the fuselage to give depth perspective to the wingman.

After a pause, the green light stopped blinking and became a steady, dim green point in the gray fog.

“Formation lights are on” Lead said.

“Actually, they’re not,” I thought to myself. “This is going to be a long night if we stay in this weather.” I tightened my focus on the green light and hung on.

After we leveled off at 20,000 feet, Lead called “Saber, fuel check, Lead’s eight thousand, tanks dry.”

I glanced quickly at the fuel gauge, located on the bottom center of the instrument panel. The needle seemed to be near the 5 o’clock position or just below the 8,000 mark. As I remained concentrated on the green light, I dared not fumble for the switch that would confirm the drop tanks had fed out.

I replied, “two is seven eight hundred, tanks dry.”

We settled in for the remainder of the flight to our target area. At least the air was relatively smooth until we reached the frontal boundary south of Da Nang. The turbulence was mild at first, little bumps that rocked the airplane. These bumps progressed to sharp, jarring motions and the green light bobbed and

weaved as I struggled to keep it centered on the side of the canopy. “Easy,” I said to myself, “don’t over control.” My concentration became intense — and as the turbulence increased, I slowly began to lose my sense of orientation in the real, three-dimensional world.

From my physiological training I knew that spatial disorientation occurred when the various sensors in the body, particularly the semicircular canals in the ear, are confused by banking and climbing/ diving motions of an aircraft. Visual cues normally override these false sensations, but in the absence of a clear visual horizon, the other bodily senses prevail. The result is an inability to accurately tell your orientation to the physical world. In extreme cases, a tumbling sensation can result. Spatial disorientation is typically a major factor in fatal, loss of control aviation accidents. This knowledge was not comforting. But it did emphasize the urgency of keeping sight of the limited visual cue I did have; Lead’s green wing tip light.

The tension now became palpable. Sweat beads formed on my forehead and I could feel dampness under my flight suit. The F-100 had no weather radar, so we basically had no choice but to plunge ahead into the gloom. Periodically, flashes of lightning would illuminate the entirety of Lead’s airplane, but against the grey background of clouds they did not provide the visual cue I needed to fight my worsening spatial disorientation. A powerful feeling crept in that we were no longer flying straight and level. Even though I knew we were basically wings level, I felt we were in a steep bank so that I was looking up at Lead’s airplane. The wing tip light was my only visual reference to counter this illusion. I ignored this sensation as best I could and concentrated desperately on holding the green light — my connection to reality — in place on the canopy. As long as I could do that — and believe in Lead — I

knew, at least intellectually, that we were OK.

The minutes now dragged on. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see St. Elmo’s fire form at the base of the wind screen as little luminescent green balls that trickled up the wind screen. From time to time, turbulence would sharply jar my airplane and the green wing tip light would dance erratically. Moments of near panic would then set in as I struggled to regain control of that light. Somehow, I fought down the sensation of disorientation and held on to my green light. I had to consciously remind myself to relax the ever-tightening grip that I had on the stick and throttle. Sweat continued to build inside my mask.

In due time, Peacock came on the radio, “Saber Four One, turn left to two eight zero, maintain, twenty thousand, contact Skyspot Control on 267.8.”

Lead replied, “Roger, left to two eight zero, twenty thousand, Saber go Manual.”

This last was a command to change the radio to the briefed Skyspot frequency. Fortunately, at Lead’s suggestion, I had preset that frequency in the manual setting on the radio control. I quickly let go of the throttle and flipped the radio control to manual. Meanwhile, Lead’s left turn to 280 was so smooth that I didn’t even recognize we were banking. But when we rolled out on heading I now felt we were flying knife edge, that is in 90 degrees of bank, and that I was looking straight up at Lead. It was a bizarre sensation.

Lead said “Skyspot, Saber Four One, check.”

I keyed the mic, “Two’s on.”

The Skyspot controller responded “Roger Saber Four One, squawk six five. You are two minutes from the IP, turn left to two seven five, maintain twenty thousand feet, set altimeter to three zero zero one.”

The IP or initial point was a point in the sky from which the final approach to the weapons release point was made. With only a few minutes to go now, I knew I only had to hold on a little longer to at least complete the bombing run.

Lead replied “Two seven five, twenty thousand, altimeter three zero zero one.”

The altimeter setting was the local atmospheric pressure reading and ensured our height above the terrain matched the calculated ballistic profile of the Mk 117 bombs we were carrying. Fortunately, only Lead needed to adjust his altimeter.

As we continued the run in, the clouds thinned enough that I had nearly a full view of Lead’s airplane. This was reassuring except that I still felt we were in 90 degrees of right bank. In this disoriented state I had this peculiar feeling that, since I was directly below Lead, when his bombs released, they would fall down on me.

A minute or so later Skyspot said, “Saber Four One, come right to two eight zero, you are on track, do not acknowledge further transmissions.”

Next Skyspot said, “Saber, left to two seven eight, you are thirty seconds from release, arm weapons.”

I reached up and flipped the weapons arm switch on the left instrument subpanel. Next followed a running commentary of small heading changes until “Saber, release on my mark.”

A pause, then “three, two, one, mark.”

At mark, I pressed the pickle (weapons release) button on the control stick and felt the airplane jump as over 3,000 pounds of ordnance was suddenly released. Simultaneously, I saw the explosive ejection cartridges on Lead’s ☛

airplane flash and was mesmerized to see the four 750 lb. bombs move smoothly away on what appeared to be a horizontal plane. It took a moment for me to accept this was just an illusion, albeit a powerful one.

After a few more moments, Skyspot said, “Good run Saber, turn left to one eight zero, contact Peacock on 236.6. Good night.”

Lead replied, “Nice run Skyspot, Saber, arm safe, go channel six,” and started a gentle left turn to head home.

I switched my radio back to preset and waited.

Presently, Lead called “Saber check.”

I replied “Two.”

Then Lead, “Peacock, Saber Four One, twenty thousand, RTB [return to base] Tuy Hoa.”

Peacock replied “Roger, Saber Four One, Tuy Hoa is bearing one fi ve zero for two hundred miles, squawk fi ve seven, flash.”

Lead “Roger, one fi ve zero for two hundred, flash.”

A pause, then “Saber fuel check Lead is four fi ve hundred.”

Again, a quick glance at the fuel gauge which sat just at 12 o’clock on the dial. “Two is four thousand” I said.

When we passed the frontal boundary heading southeast, the air again became relatively smooth. We were fl ying basically straight and level, but we were in and out of the clouds. While I still didn’t have a visual reference other than Lead’s wing tip light, my disorientation slowly began to recede. I began to relax a little.

About 30 minutes later, Peacock called “Saber Four One, Tuy Hoa bears one six zero for twenty-fi ve miles, contact Tuy Hoa approach on 233.2. Good night.”

Lead replied “Roger, Saber channel fi ve, go.”

I glanced at my TACAN readout. TACAN is a radio navigation device that gives direction and distance to the selected station. I had not changed the TACAN frequency since takeoff so it was still tuned to Tuy Hoa. The bearing needle pointed just right of 12 o’clock. For the fi rst time since join up, I had a sense of where I was in the physical world. I switched the radio to channel fi ve.

Lead, “Saber, check.”

“Two,” I replied.

Lead “Tuy Hoa approach, Saber Four One.”

Approach Control answered, “Roger Saber Four One, turn left to one four zero, descend to ten thousand, altimeter two niner niner six.”

Lead “Roger, left to one four zero, ten thousand, approach, bring Two in first, he’s a little low on fuel.”

This direction from Approach Control was to separate the flight and gain spacing between the two aircraft for individual approaches.

Lead replied, “Roger, Two you’re cleared off.”

I keyed the mic, “Roger.”

I moved the stick gently to the right to roll out of the turn we were in and watched the gap between us quickly widen. Lead disappeared into the grey clouds. The green light was gone. As I turned my head to look at my instruments, suddenly, I had a violent sensation of tumbling. I was in a dark, grey haze with no visual reference to the physical world. I had no idea what was up or down and what to do to control the airplane. I froze. I stared helplessly at the instrument panel and tried to fi ght back the rising panicky feeling. Seconds passed.

Then a small voice in the back of my mind said, “Trust the attitude indicator. Trust the attitude indicator.” It was the voice of my primary instructor from pilot training. As I had struggled to right the airplane on my spatial disorientation training flight, my instructor had calmly said, “Focus on the attitude indicator. Trust the attitude indicator, it’s your only friend until the disorientation passes.”

The attitude indicator is a basic flight instrument that gives the pilot a quick indication of the aircraft’s orientation relative to the horizon — whether the aircraft is climbing or diving, or banking, or a combination of those.

“Roger,” approach control said, “Saber Four Two roll out heading one four zero, descend to five thousand, Saber Four One, continue your turn to one zero zero, maintain ten thousand.

I looked hard at the attitude indicator in the center of the instrument panel. It’s a ball, half gray and half black, with a symbol representing the airplane’s wings in the center. The ball rotates behind the wing symbol to show a climb or dive, bank left or right. Mine now showed the airplane in slight climb and right bank. “Level the wings,” I said to myself, “Keep the gray part up and the black part down. Now hold it there.” The panic receded. The feeling of tumbling

If you have traveled recently, or are planning to travel this holiday season, I’m sure you know that the price of admission at similar museums is upwards of $25 per person!

As you know, it costs money to keep a museum like this

FUN and educational for future generations. That’s why I am asking for your help again.

Will you send another gift to help keep the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force™ engaging and entertaining for generations?

Your gift of $25 or more makes the Museum an EXCITING place to visit plus helps preserve, protect, and promote our military history for generations to come.

Will you please make your most generous gift today? Here’s how you can help!

Scan or visit www.afmuseum.com/journal to make another gift to fund the special exhibits and activities that make the Museum an exciting place to visit and support the other great work of the Air Force Museum Foundation.

Scan here to give a gift of:

Your Gift Today will Keep the Museum an Exciting Place to Visit!

$25 to help 1 visitor like you experience the excitement of the Museum $50 to help 2 visitors like you experience the excitement of the Museum $100 to help 4 visitors like you experience the excitement of the Museum or a gift of your choice to provide as much help as possible

This is just the beginning – you can make sure quality exhibits and fun programs continue!Matthew Allen Photography