It’s my privilege to present the February 2025 edition of CONNECT.

There’s been some pretty crazy snow across the country the past few weeks, but I hope that you’ve had a good start to the new year. Those of you who have had to go out and shovel snow, I hope it hasn’t been too much work. We’ve got some absolutely stellar articles for you to read while you’re hiding from the cold.

First, in Arts, General Section Editor Maritza De La Peña gives us an insightful look into a master hanko craftsman. In New Year, New Hobby, Úna O'Shea teaches us all how to make our own mizuhiki designs, carrying on from an introduction to the craft last issue.

If you’re looking for your next book to read while sitting by your heater, Assistant Head Editor Brooklyn Vander Wel could tempt you with their review of A Hundred Years and a Day in the Culture section. While you’re there, you can also learn the history of one of Japan’s most infamous counter-culture groups— Sukeban.

After reading Fashion Editor Sabrina Greene’s piece Clothes in the Classroom, you might be inspired into using your own style choices to drive class discussions. While you’re in a learning mood, be sure to check out When Worlds Collide, where a Speech-Language therapist teaches us how we can communicate more effectively with English-learners.

If you’re like me and love learning about Japanese crafts, check out Carving a New Life, about a European woodcarver who moved to the depths of the countryside to study in a town of woodcarving masters. In Travel, Editor Jon Solmundson could set you up with your summer travel plans to get you through the cold months in Four Festivals in One Week.

I’d also like to take a moment to thank all of the people who have been contributing to our continuing photography contests on social media. It’s a pleasure seeing all the talented people that make up our small community. If you’d like to enter our next competition, follow us on Instagram to get the latest updates!

Thank you again for reading, and Lang may yer lum reek!

Head Editor of CONNECT Magazine

CONNECT | Arts

7 The Art of Hanko: Works of a Third-Generation Seal-Maker

10 Mizuhiki: The Basics

CONNECT | Culture

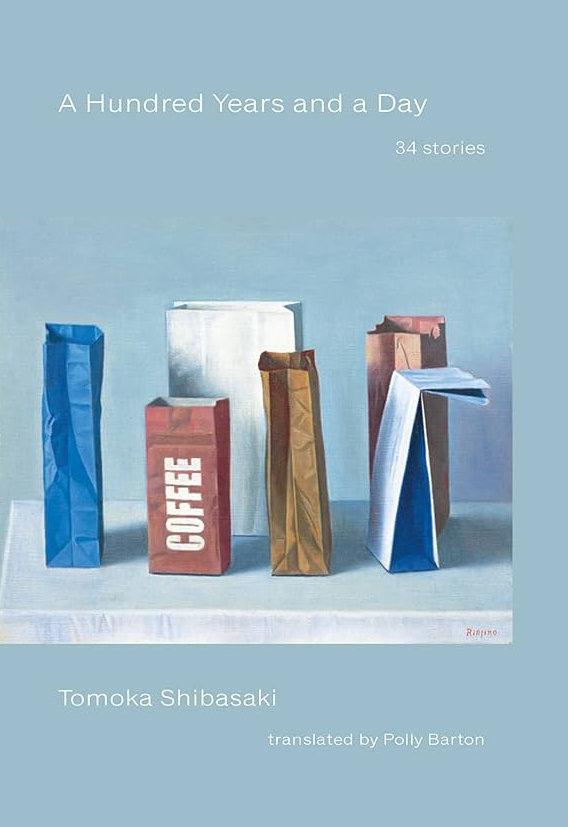

12 A Hundred Years and a Day: 34 Stories Book Review

16 Sukeban: Japan’s 70s Girl Gangs

CONNECT | Entertainment

23 Tokyo Beats: Spinning Vinyl with EVA

26 Switching Bodies: The Transformative Power of Crossplay

CONNECT | Fashion

33 Clothes in the Classroom: How ALTs Use Fashion for Cross-Cultural Connection

38 Countryside Cuts: One Rural Hairstylist’s International Journey and Its Legacy

CONNECT | Wellness

44 Interview with an Elementary School Nurse

CONNECT | Language

48 Fukiko’s ESL Academy: A Globetrotting Teacher Reveals Her Rich History as an Educator and Language Learning Mindset

52 When Worlds Collide: Bringing Speech-Language Therapy into the Classroom

CONNECT | Careers

57 The Anatomy of a Japanese Business Card

CONNECT | Community

64 Carving a New Life: The First European Woodcarver

69 The Binding of Books: Turning a New Page with Koen Book Club

CONNECT | Travel

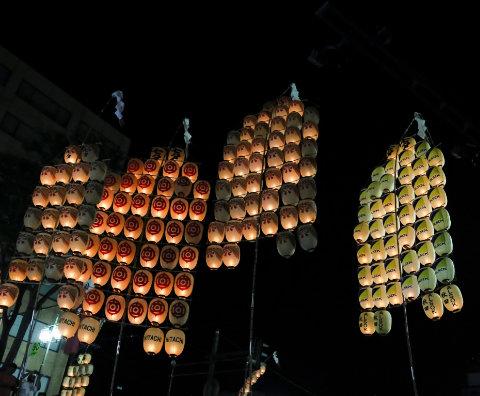

73 Four Festivals in One Week: Touring Tohoku’s Biggest Celebrations

78 Shirakawa-Go: Japan’s Hidden Traditional Village

HEAD EDITOR

Mike Taylor

This is a cop-out but I’m a sucker for root vegetables. Except sweet potatoes. I hate sweet potatoes so much I wrote a diss track about them.

ASSISTANT HEAD EDITOR

Brooklyn Vander Wel Cucumbers, or as they should be referred to as, “Cukes.”

ADMIN ASSISTANT

Dianne Yett

Butternut squash broke me. It’s the gourd of choice for pumpkin pie in a country without canned pumpkin, and it is also the hardest to find.

HEAD DESIGNER

Renee Stinson

Broccoli! How is it that it's stereotyped as the gross vegetable kids hate in cartoons?

ASSISTANT HEAD DESIGNER

Taylor Sanders

My favorite vegetable is broccoli. I use it so often for cooking and it’s high in protein, fiber and other nutrients.

SECTION EDITORS

Maritza De La Peña

You cannot go wrong with root vegetables. Jicama, potatoes, garlic, lotus root, beets, ginger—it’s impossible to pick just one.

Kianna Shore

My favorite vegetable is cabbage. You can make kimchi and okonomiyaki out of cabbage, two of my favorite foods!

Allegra McCormack

Garlic and onion. Just cooking them in butter will make everyone in smelling distance believe you’re an amazing chef.

Úna O’Shea

As a suffering vegetarian, I like most vegetables, but there's a special place in my heart for mushrooms and broccoli.

Sophia Maas

Kagome vegetable juice. Sometimes I just can’t be bothered to include vegetables into my everyday diet any other way.

Tori Bender I could eat sweet potatoes every day!

Chantal Gervais

All time reigning champions: carrots and peas. Otherwise, lotus root, sweet potato, and kabocha.

Sabrina Greene

Garlic, no contest. The correct amount is double the recipe.

Kalista Pattison I don’t believe in vegetables. Something I learned while getting my degree in biology is that botanically speaking vegetables don’t exist. Garlic is a bulb, a potato is a tuber, a pumpkin is a fruit, spinach is a leaf, a carrot is a root, and so on…

Chloe Gust

Joseph Hodgkinson

It has to be potatoes purely because of their versatility.

Jon Solmundson

The onion is the king of all vegetables. How can one humble orb contain such a diversity of flavour? Mouthtingling crunch, subtle umami, or caramel-sweet char - the choice is yours.

Kimberly Matsuno

It’s not so much a vegetable as it is… well… a leaf, but lately I’ve been in love with shiso. It’s such an easy plant to grow and adds a wonderful flavor to so many dishes.

Jessica Barton Pumpkin or sweet potatoes.

Vaughn McDougall

The controversial-but-everdelicious brussel sprout!

Indy Inoue

Sweet potatoes and taro root. Literally the most versatile food on the planet. Baked, fried, candied, chips, I’ll eat ‘em all.

WEB EDITORS

Austin Fontenot

Marco Cian

Probably broccoli. I eat a lot of broccoli. And chicken.

Abigayle Goldstein

I live and die for Brussels sprouts. Especially roasted with some Kewpie and Sriracha.

Zoë Vincent

Red peppers / bell peppers / capsicums (choose your favourite wording). They’re so versatile and cheerful.

Katherine Winkleman Carrots, raw or roasted.

Kaitlin Stanton

Tomatoes (I know I know, they’re technically a fruit) are so versatile and have made their way into so many cultural cuisines.

Aidan Koch

Spinach–great by itself, even better in a salad or recipe!

Taylor Hamada

Cucumbers because you can create so many different flavored side dishes! Oldfashion pickles, kimchi, tuna, sesame and don’t forget the MSG, obviously (iykyk).

Jedidah Walcott

Favourite vegetable? Ew! Who likes vegetables? Wait. Is corn a vegetable?

Jenny Chang

Eggplant, onion, potatoes, gobo, cucumber, bell pepper… I love all vegetables, please don’t make me choose.

Mark Christensen

Chantal Gervais

Sabrina Greene

Chloe Gust

Joseph Hodgkinson

Kimberly Matsuno

Sophie McCarthy

Úna O'Shea

Maritza De La Peña

Alice Polaschek

Jon Solmundson

Mike Taylor

Brooklyn Vander Wel

COVER PHOTO

Fanny Orange

This magazine contains original photos used with permission, as well as free-use images. All included photos are property of the author unless otherwise specified. If you are the owner of an image featured in this publication believed to be used without permission, please contact the Head Designer, Renee Stinson, at visualmedia.connect@ajet.net. This edition and all past editions of AJET CONNECT can be found online at https://connect.ajet.net/category/online-issues/ or on our website. Read CONNECT online and follow us on ISSUU.

ARTS EDITOR

Sophia Maas

Kagome vegetable juice. Sometimes I just can’t be bothered to include vegetables into my everyday diet any other way.

ARTS DESIGNER

Indy Inoue

Sweet potatoes and taro root. Literally the most versatile food on the planet. Baked, fried, candied, chips, I’ll eat ‘em all.

ARTS COPY EDITOR

Aidan Koch

Spinach–great by itself, even better in a salad or recipe!

CULTURE EDITOR

Joseph Hodgkinson

It has to be potatoes purely because of their versatility.

CULTURE DESIGNER

Taylor Sanders

My favorite vegetable is broccoli. I use it so often for cooking and it’s high in protein, fiber and other nutrients.

CULTURE COPY EDITOR

Zoë Vincent

Red peppers / bell peppers / capsicums (choose your favourite wording). They’re so versatile and cheerful.

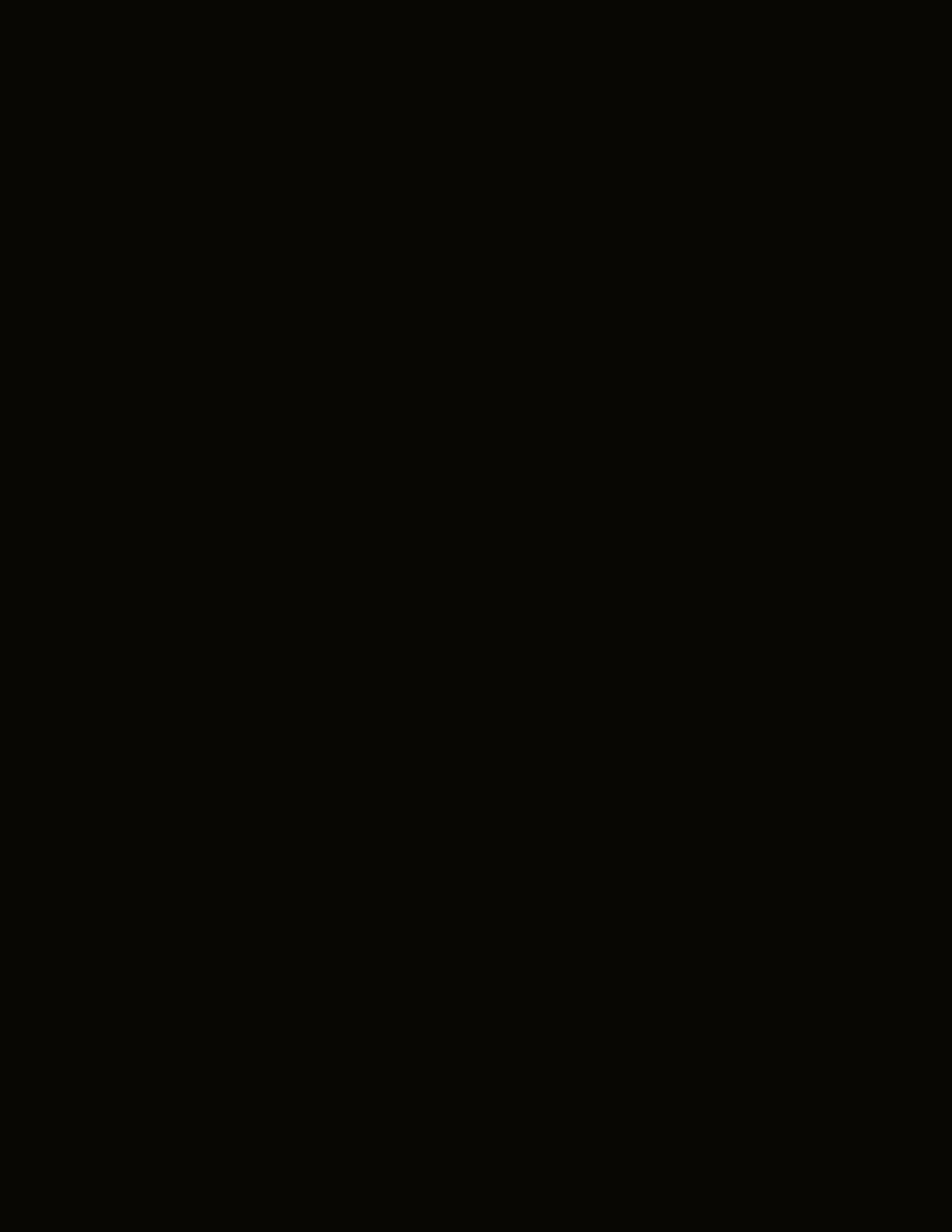

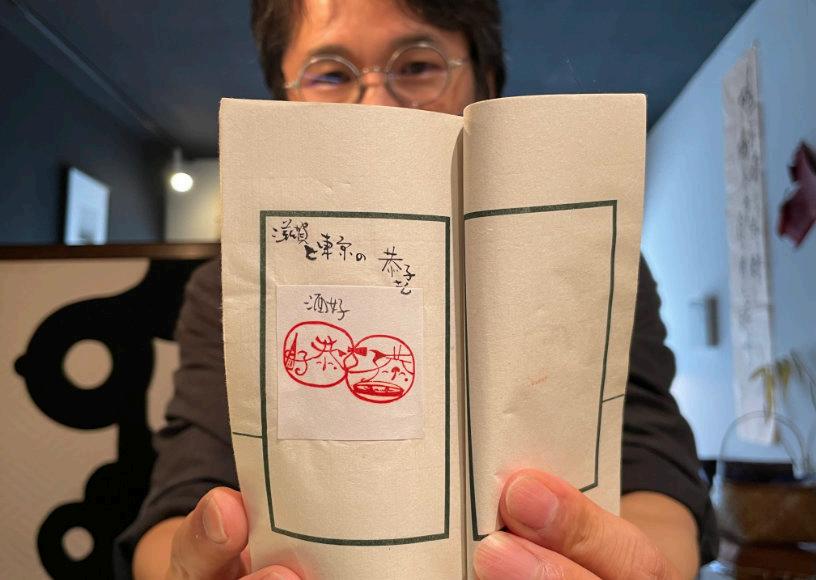

By Maritza De La Peña (Nara)

Translated by Katherine Winkleman (Wakayama)

Kokoan Cafe is a monument to owner Kouko Saito’s works.

The walls are covered in art, showcasing his talent as an artist, calligrapher and, above all, seal maker. Through a small window to the left of the entrance is a glimpse of his office—a small table, seal-making tools neatly arranged.

For three generations, Saito’s family has made hanko, personalized name seals, here in Omihachiman, Shiga.Amaster seal-maker, his business now doubles up as a cafe. He says the joy customers have when they receive their seals is what most inspires his work. The hanko is an essential part of daily life. It's most commonly used on official documents instead of a signature, such as when signing a lease, opening a bank account, or completing business forms. The seal is typically a thin cylinder about two centimeters wide. The cheapest seals can easily be found in 100 yen shops.

However, some people go to shops such as Kokoan Café to purchase a custom hanko. These might be purchased as special gifts or to commemorate a significant moment instead of day-to-day use.

Learn more about Kouko’s café and a selection of his works here.

““I’m not just carving characters into a stamp; I’m thinking about what this person is doing with their life and how we want to express that in the hanko.”

Talking with the customer is essential in this kind of job. Kouko needs to determine the hanko's recipient, the purpose of the hanko, and what emotions should be represented. Through conversation, he is able to sketch up ideas that he shares with the customer before carving the final product.

“I’m not just carving characters into a stamp; I’m thinking about what this person is doing with their life and how we want to express that in the hanko.”

There is a dictionary that hanko-makers use for standard designs. It can be difficult to break away from this pattern, but Kouko's designs center around personalization. In the café, there are signs inviting visitors to flip through the little blue books on display. The books are filled with previous stamps designed by Kouko himself. He showed a few, opening the pages to reveal his works. Thin, delicate lines of kanji curve into familiar images, such as a castle or a bottle of sake. Each one incorporates the meaning of the word into the image itself.

When Kouko creates a stamp, he uses a magnifying glass to carefully view the carvings, all the while quickly spinning at a block used to hold it in place. His right hand gently grips the blade handle between his fingers as he presses down to carve the characters. The end product is a beautiful, original piece of art.

The design must be carved like a reflection so it stamps the correct way. Because of this, it can be difficult to master.At the same time, Kouko embraces the irregularities that come with hand-carving. There might be bumps or divets in the wood that become part of the unique design.

“Through making the hanko by hand, maybe you can feel the warmth that comes out of human creation,” Kouko explains.

Despite the amount of skill it takes to master this technique, hankomaking itself is something that is easily accessible for anyone to try. Kouko previously traveled to the United States, where he worked with a range of people, from seniors inAustin, Texas to counselors in Boston, Massachusetts, to kindergarteners. With the kindergarteners, Kouko had them carve into styrofoam and the kids collectively stamped their creations onto a large tree he had drawn. Back in the café, he shows off a collection of stamp marks from a workshop inAustin where the designs included different kanji characters, or images such as cats, rainbows, mountains, and the moon integrated with English letters.

While Japanese culture can sometimes be associated with strict customs, this type of freeform learning allows anyone to experience this art form.

This opportunity allowed Kouko to share a part of tradition that might be lesser known outside of Japan. “For calligraphy, there are many artists who go abroad and do workshops, but there aren't many for seal carving.”

Kouko shared an experience of an elderly woman in his community who had to move away. In her backyard, there was a tree that had been precious to her. He made a hanko using the wood of this tree so that a part of it could always remain with her. Similarly, he made a hanko for his own son's coming-of-age day using the wood from a bay tree that had been planted when his son was born.

““For calligraphy, there are many artists who go abroad and do workshops, but there aren't many for seal carving.”

Since 2020, there has been a slow attempt by the Japanese government to phase out the daily use of hanko. The use of these seals can be considered outdated, especially in the age of digitalization.

The thing is, seals have existed throughout history in many different cultures. Kouko points out that in ancient Mesopotamia they also used similar stamps.As an artisan who is strongly motivated by the happiness he receives from those who commission his work, he believes that seals are a part of us as humans.

“For Japanese people, there is a lot that goes into choosing a name for a child. You want to give a name that will bring the child happiness. When we make a hanko, we want to put that happiness into the hanko, and then it becomes a sort of amulet. So, in this age of digitalization, things can come and go very quickly, but seals aren't going anywhere.”

Katherine Winkleman is a third-year ALT and Prefectural Advisor in Wakayama

She enjoys reading, studying Japanese, and crocheting. You can find her trying out a new dinner recipe or attempting to pet the neighborhood cats.

Una O’Shea (Ishikawa)

ISachiko Sakamuro (Ishikawa)

n our last issue, we introduced Mizuhiki. To refresh your memory, Mizuhiki is a traditional craft that uses coloured and starched threads of paper (also named mizuhiki) which are twisted into knots to create a variety of designs. It is most often seen as a decorative addition to envelopes for occasions like weddings, but it is becoming increasingly popular in jewellery and even in visual art. Its appeal lies in both its versatility of use, and in its accessibility. Now that you have learned about this new artform, why not try it for yourself?

Sachiko Sakamuro, a Mizuhiki artist and teacher in Ishikawa, has very kindly provided instructions for a simple Mizuhiki knot.

Ume-Musubi broach made by Una O’Shea

To make Mizuhiki art, you’ll need a few things.

First, the mizuhiki threads. These are available in most large craft stores. Those who are just trying it out might opt for small kits with a mix of colours (and even instructions), but large bulk quantities of single-coloured mizuhiki are also available. Mizuhiki threads are also readily available online.

You will also need scissors to trim off excess threads, and glue may be needed to finish the design, or to attach it to whatever it is decorating. For some designs, small clips are useful to keep your threads in order.

Throughout the process, try to remember two important things: Have fun!And keep your threads flat.

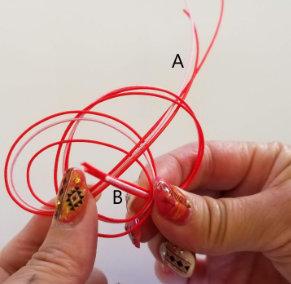

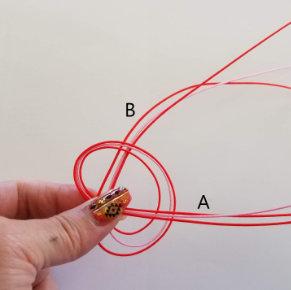

Make a teardrop shape by crossingA over B, and hold the crossing point in your right hand.

Awaji-Musubi is a staple knot style in Mizuhiki design. It can be used as a standalone decoration, or it can be the foundation of more complex designs. To start, it is recommended to use three mizuhiki, but you can try using less or more depending on your desired style.

BringAaround and on top of the left side of the teardrop, and hold whereAcrosses the teardrop in your left hand.

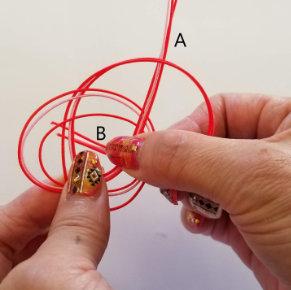

Thread B under the right loop, and come through to the front.

Let go with your right hand and adjust the shape until it looks like the picture.

Then, thread B into the centre loop, from the front to the back.

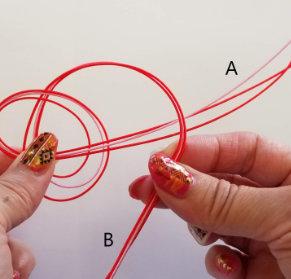

Pull the threads on either side carefully, adjusting the shape. Be careful to keep the threads flat and close together.

Now, bring B around and overA.

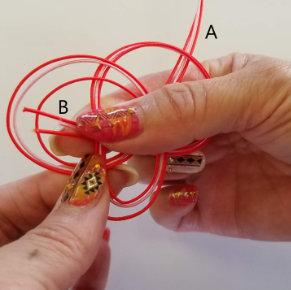

Finally, thread B through the left and final loop, from the back to the front.

Your awaji-musubi is finished!

Congratulations, you are now officially a Mizuhiki craftsperson!

Úna O’Shea has lived in rural Ishikawa for two years. She enjoys long walks on the beach. Very long walks on very long beaches. Sometimes the very long walks are actually quite short drives on Japan's only beach road, the Chirihama driveway near Hakui, Ishikawa, where you can open your windows and let the wind rush through your hair as you drive along eight beautiful kilometres of sand and waves.

Sachiko Sakamuro has been teaching Mizuhiki in Ishikawa for around five years. She started simply because she thought Mizuhiki jewellery was beautiful, but a little expensive. After gifting some of her creations to friends, she received such positive feedback that she began selling her own jewellery and offering classes in the area.

Sukeban (スケバン), a term that roughly translates to “girl boss” or “female delinquent leader,” refers to the all-female gangs that emerged in Japan during the 1970s and 1980s. Known for their distinctive uniforms, rebellious attitudes, and rigid codes of conduct, these groups offer a fascinating insight into the intersections of gender, culture, and resistance within Japanese society. Though their heyday has passed, the legacy of Sukeban remains a powerful symbol of resistance and individuality in Japanese culture.

In the decades following World War II, Japan emerged as a major industrial power, achieving rapid economic progress. However, traditional gender roles remained deeply entrenched, with women expected to conform to ideals of femininity centred on domesticity, obedience, and respectability.

During the 1960s and 1970s, Japan witnessed a surge in youth rebellion, driven by dissatisfaction with the rigidity of societal norms, the pressures of academic success, and the conformity demanded by postwar industrial capitalism. Male-dominated youth gangs such as Bosozoku (暴走族) emerged during this time, drawing inspiration from American biker culture.

These groups openly defied societal expectations through subversive behaviours, including illegal street racing and disrupting public spaces with large, boisterous gatherings. Another form of rebellion manifested in Bancho (番 長) groups, maleexclusive cliques of high school delinquents. Influenced by the yakuza, these gangs adhered to strict hierarchical structures and organised annual leadership elections.

Sukeban emerged as the female counterpart to male gangs, offering young women a space to rebel while also redefining femininity on their own terms. These groups gave women, often high school students or young adults, an outlet to challenge societal expectations and assert their independence. Rooted in school culture and youth rebellion, Sukeban redefined femininity through solidarity, defiance, and a rejection of traditional norms.

“The Sukeban used fashion as a striking and symbolic critique of traditional femininity, transforming the Japanese schoolgirl image from one of passivity and obedience into a bold assertion of individuality and defiance.”

This aesthetic rebellion was not just about breaking rules—it was a reimagining of identity and empowerment.At the heart of their style was the modified school uniform. Sukeban members famously wore long skirts, directly opposing the hyper-sexualised portrayal of schoolgirls in Japanese media. These skirts became a visual declaration of their refusal to be objectified. Their uniforms were often customised with intricate embroidered slogans or gang-specific symbols, such as phrases like “loyalty and defiance” or detailed floral designs, blending rebellion with artistic expression. Many also wore bold, unconventional hairstyles, further defying societal expectations of how women should present themselves.

Sukeban members adhered to a strict code of conduct that emphasised loyalty, discipline, and respect for the internal hierarchy. Among the most notable rules were prohibitions on romantic relationships, which were viewed as potential distractions from gang commitments, and a ban on the use of hard drugs. This latter rule was particularly significant, as it set Sukeban apart from more dangerous or criminally inclined groups, underscoring their focus on rebellion within defined limits.

Violations of these rules or acts of disrespect toward superiors were met with strict disciplinary measures, a practice referred to as “lynching.” Punishments ranged in severity and could include physical beatings, public humiliation, or, in extreme cases, being burned with cigarette butts. These harsh measures were designed to enforce discipline, maintain order within the group, and ensure unwavering loyalty, which was critical to the survival and strength of the Sukeban subculture in the face of widespread societal condemnation¹.

Sukeban leaders wielded power in a way that emphasised female solidarity and mutual respect, offering a rare opportunity for young women to assert authority. Leadership roles allowed them to foster a sense of empowerment, even if restricted to the boundaries of their rebellious community. In mainstream society, where women were frequently confined to the roles of housewives or faced limited opportunities for career advancement, Sukeban leadership represented an alternative vision of independence and influence.

Like their male counterparts, Sukeban engaged in smoking, fighting, and petty crimes such as shoplifting, though they rarely participated in serious violence or criminal activities. Rivalries between Sukeban gangs or even between schools were not uncommon. Maintaining dominance and respect was a critical aspect of gang dynamics, with confrontations often serving as a way to assert power and defend their status. Members sometimes carried weapons such as knives, chains, or razor blades concealed under their skirts. These weapons, however, were largely symbolic, serving as tools of intimidation and self-expression rather than objects of harm. Carrying them represented independence, toughness, and a rejection of traditional notions of femininity.

“Through their rebellious and, at times, intimidating public personas, Sukeban members took control over how they were perceived, pushing back against societal expectations that sought to confine them.”

Their defiant and unapologetic attitudes became a defining feature of the subculture, ultimately elevating it to a matter of national concern. Focused on rebuilding the nation, post-war Japan placed a high value on conformity and societal order. Any behaviour that deviated from these ideals, especially among women, was seen as a threat to the moral fabric of society. The media frequently sensationalised Sukeban activities, portraying members as violent and immoral. This heightened the stigma they faced, often making them targets of police surveillance and societal scorn.

Sukeban had a major influence on Japanese media, particularly in entertainment. Their rebellious flair inspired the “Pinky Violence” genre, which celebrated bold and defiant female characters. One of the most famous examples is the Sukeban Deka franchise, featuring a Sukeban girl turned undercover detective armed with a yo-yo. At their peak, Sukeban gangs such as the Kanto Women’s Delinquent Alliance boasted impressive numbers, reportedly having over 20,000 members². Over time, however, the Sukeban phenomenon began to fade. Like many subcultures, Sukeban transformed as extensive media exposure softened their gritty and rebellious image into stylised archetypes for broader entertainment. What once symbolised ideals of freedom and rebellion gradually became diluted for mass appeal³.

Despite its decline, the Sukeban spirit and visual legacy endure in modern Japanese culture. It remains a celebrated symbol of resistance, individuality, and female camaraderie, often romanticised in nostalgiadriven media. Sukeban is now fondly remembered as a significant chapter in Japan’s rich tapestry of youth subcultures, a testament to the power of defiance and self- expression in challenging societal norms.

Originally from London, UK, Joseph is a secondyear ALT in Hyogo Prefecture who loves exploring Japan and immersing himself in its rich culture and history. Aside from writing, his interests include playing the guitar, volleyball, coffee, and retro gaming.

1. Sukeban: Japanese Girl Gangs - Easy Sociology

2. 1970’s Sukeban Subculture: Japanese Delinquent Gangs | japadventure.com

3. Sukeban - The Forgotten Story of Japan’s Girl Gangs — PERSPEX

ENTERTAINMENT EDITOR

Chantal Gervais

All time reigning champions: carrots and peas. Otherwise, lotus root, sweet potato, and kabocha.

ENTERTAINMENT DESIGNER

Indy Inoue

Sweet potatoes and taro root. Literally the most versatile food on the planet. Baked, fried, candied, chips, I’ll eat ‘em all.

ENTERTAINMENT COPY EDITOR

Kaitlin Stanton

Tomatoes (I know I know, they’re technically a fruit) are so versatile and have made their way into so many cultural cuisines.

Evan Hurlocker is set to take the stage on a late Sunday afternoon. Acrowd of people fill a soba shop that normally seats four people, five if you don’t mind being a little too close.

For Evan, known in the scene as EVA(the name chosen by his wife as a nod to Neon Genesis Evangelion), venues like this are where he feels he can connect. His preferred locations are where he can play to small groups of around 15 people, where they can talk, dance, and groove freely, even after the last train. When the last train is long gone, he says,

“Whoever is there has already decided ‘I’m here for it. Let’s go.’”

The owner of the restaurant is behind the bar, announcing each DJ by speaking into a wooden spoon as if it were a microphone.

The crowd cheers. Steaming pots of nabe are ferried to the patrons outside, a token to thank them for braving the cold while they listen to the beats being spun. As Evan steps up to the plate, there is barely room to move inside. The streetside audience makes their way into the unseen spaces. Music flows and everyone grooves as much as they can. The beats are supreme, chill but with enough snap, you can’t stop your body from moving. For Evan, DJing isn’t just about playing, it’s about intimacy and connection— community. “[Tonight] people showed up from all different walks of life and everyone is incredibly warm. . . it wasn’t like this [community] was already preplanned and people coming in are an outsider. We developed a community tonight.’’

“Enjoying music, dancing, and connecting with people is something we can’t explain.”

It’s been five years since Evan started working professionally, but he’s been involved in the electronic music scene for more than a decade. Recalling a homestay in Japanduringhishighschoolyears, Evan says music was something that brought him together with likeminded, less studious classmates.

“We used to hang out under the stairwell and just do nothing. But it was fun because they had a boombox and a Beastie Boys cassette tape, so we connected on that.” One of the friends he made had a brother in the techno scene, andwouldshowEvanthetrackshe was working on. “It had that little something special, something different… That always stuck with me.”

When he moved back to Tokyo as an adult seven years ago, he jumped back into the music scene feet first. He didn’t find it hard: he simply walked through the door, started shaking hands, and hung out. “[In Tokyo’s club community], most people have a really open global mindset. They’re always looking at music from a not solelyJapanese perspective. So they’re the type of people who enjoy cultural exchange.” Through showing up and having a good time,Evan immersed himselfin the community.Afteradecadeofbeing in the audience, he thought “I need to express myself too.”

Struggling to discover his own music identity, Evan went back to hisroots.FromPortland,Oregon, he grew up during the early to mid-2000sondrumandbassand jungle music. Neither genre quite took off in Japan, so he was quickly priced out of those styles. Revisiting his need to express himself, Evan realized the key was to focus more on his own likes. The answer: soulful house, a genre that quickly came and went in the west, but took hold in Japan.

This was thanks in part to English funk and soul band Jamiroquai, whose popularity exploded in Japan during the 1990s. Soulful house records were cheap, and theDJwasbroke.Fromthere,he wasquicklyledtoUKgarage,the forefather of dubstep. The genre is well known for high beats-perminute that gets people up and dancing. He says, “These are the kinda things I can play in the club that people pick up on. They have a little more soul.”

10 PM, it’s an early night for Evan. The crisp January air bites at him as he layers on his snowboard jacket and makes plans to play at another club that evening. Thankfully the next day is a holiday, so taking his equipment on the train when it starts running again won’t be an issue. If it wasn’t a public holiday, Evan would be back at his day job come 8:30 a.m. tomorrow morning.

It’s tough and it doesn’t pay well, but he says it’s not about that.

“If you’re going to DJ in Tokyo, you’re never gonna make any money. Ever. It can’t be about the money.” Instead, he says there’s something more intangible.

"Nowadays, we tend to forget that feeling is an important aspect of our lives. Enjoying music, dancing, and connecting withpeopleissomethingwecan’t explain. You walk into a place and you start enjoying it. You can’t really say why, it’s just a feeling."

Chantal is the Entertainment Editor of CONNECT. She is an advocate for the term “pencil crayons” over “color pencils” and is an aggressive colorer.

Cosplay, or “costume play,” is a popular medium for fans to bring their favorite characters and creatures to life. Through a skillful mix of crafting, makeup, and acting, people are able to transform themselves in amazing ways. As the mecca of cosplay with countless events throughout the year, Japan is arguably the best place in the world to see these creators in action.

Of the many types of cosplay, one that is especially fascinating is “crossplay.” In this style, a cosplayer will recreate the appearance and mannerisms of characters of the opposite gender. To learn more about this unique form of costuming, CONNECT reached out to two talented cosplayers in the Japanese community, Mamemayo and Salina, who agreed to share their personal experiences and insight on the subject.

Mamemayo is a 2018 and 2024 Representative for Team Japan at World Cosplay Summit, and the Grand Champion of WCS 2024. In addition to making costumes, she also travels the world as a cosplay judge, producer, and writer for COSplay MODE Magazine.

Q: Could you tell us a bit about yourselves and what you do as cosplayers?

Mamemayo: I am a cosplayer in Japan who makes a living off of it. I have also worked as a stunt double and worked with a troupe performing plays and dramas. My strong suit is performance and posing.

Salina: Hello everyone! I am Salina, a cosplayer in Japan. I love anime, movies, and crafting things so I make wigs, garments, and weapons by hand and do my own makeup. I also love to cosplay my favorite characters with all I’ve got! My dream is to become a world-class cosplayer!

Q: When picking your cosplays, do you have preferences for male or female characters in general, or does it depend on the character themselves?

Mamemayo: I cosplay male characters, especially shonen boys. I have also cosplayed a lot of girl characters. I’m short so I tend to choose those kinds of characters.

Salina: I love shonen manga so I tend to cosplay a lot as a boy. I especially love Kaiju No. 8. For Captain Narumi’s cosplay, I made a 4m weapon, even installing it with lights. It’s made with love and respect!

Q: How did you first get into crossplay? What was that experience like?

Mamemayo: The first friend I made when I entered high school was a cosplayer. They invited me to join so I started. The first cosplay I did was Naruto’s Iruka-sensei when he was a child and a bit crazy. It was probably from that choice where I started choosing characters that made use of my short stature.

Salina: I started cosplaying because I admired all of the people crossplaying I saw in magazines. Also, I had so much fun going to cosplay events with my friends. “I want to make my favorite characters even cooler!” I always thought, so I set my eyes on becoming a cosplayer.

Salina is the Tochigi Preliminary Qualifier for the World Cosplay Summit 2025. She has also won the COSPLAYAWARD 2023 Modeling Award, as well as the WCS 2024 Japan Costume and Special Jury Awards.

Q: What are some challenges that come with crossplaying male characters?

Mamemayo: The physique. Women’s bodies and faces are more round, so I do what I can with editing and makeup to have a more male physique. Shonen characters still have a bit of youthful roundness left in them, but I still have to be careful with posing and editing around the butt area. If it seems too big it tends to look more on the feminine side. I also have to be mindful of standing or emoting more masculine.

Salina: I am a petite woman, so my biggest issue is trying to portray a manly figure. I do several things to bring out the boyish-ness in my costumes such as making the waist and hips slimmer and adding shoulder pads to give the illusion of broad shoulders. In order to hide the fact that I’m wearing heels, I fill the gap to look like regular shoes. I also imagine myself as an actual man to prevent any girlish behaviors from slipping through.

“Cosplaying filled with love and respect for the characters is what is most important to me.”

Q: Do you feel people treat you differently when you crossplay?

Mamemayo: As I mentioned before, I tend to cosplay younger boys and girls so I often get talked at like a real baby or a child lol. I myself am a 30-yearold adult, so it is a bit of a weird feeling.

Salina: I’ve never noticed if people treat me differently in cosplay. It’s more important how I feel about myself than what other people think of me. Cosplaying filled with love and respect for the characters is what is most important to me. Being able to cosplay my favorite characters to the best of my ability is such an awesome feeling. If I could spread

that joy even a little bit to others I would be happy!

Q: Who has been your favorite male character to crossplay?

Mamemayo: My favorites would have to be Jump heroes like Naruto or Deku. I want to live like them and admire them.

Salina: That would have to be Kaiju No. 8’s Gen Narumi! The gap between his silly side and then his switch to battle mode is so cool, he’s the

best. Gen Narumi is actually a really hard worker and is so considerate of his friends; I really respect that. It’s actually thanks to making his 4m weapon, the GS-3305, that got me so hooked on sculpting! He’s changed my life, and for that he’s my hero! Besides Kaiju No. 8, I also love Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure and The Legend of Zelda!

“Don’t worry about what you are good or not good at. If you have a particular favorite character, give it your all and have fun cosplaying them!”

“Even if you are short or you have a feminine body, with posing, makeup, editing, and whatnot you can change your gender! Have fun crossplaying!”

Q: What advice or tips would you give to people who would like to crossplay themselves?

Mamemayo: Even if you are short or you have a feminine body, with posing, makeup, editing, and whatnot you can change your gender! Have fun cross-playing!

Salina: Don’t worry about what you are good or not good at. If you have a particular favorite character, give it your all and have fun cosplaying them! I’m sure there are those that might worry about the quality of their cosplay or how others may treat them… But, I’m sure that cosplaying would be a wonderful experience and you’ll meet some amazing people. Through my cosplay I've been able to

meet so many people, exchange ideas, and make friends all over the world!

I believe that cosplaying can put more smiles on people’s faces. If you ever get stuck in your cosplay or have something you’re not sure about, don’t be afraid to look it up online or in cosplay magazines. There is so much information out there. Also, if it’s helpful to anyone I share information and pictures on my social media. I hope that everyone can have a fun time cosplaying!

Thank you for taking the time to interview with us! We wish you both good luck in your travels and cosplay challenges!

Mamemayo’s travels can be seen on her social media on X and Instagram.

Salina’s creations and modeling on can be found on her social media X, Instagram, and Tiktok.

Mark Christensen is a former fifth-year Fukuoka ALT from Snohomish, Washington with a passion for nature, culture, and cosplay. You can follow his photography on X and Instagram.

FASHION EDITOR

Sabrina Greene

Garlic, no contest. The correct amount is double the recipe.

FASHION DESIGNER

Taylor Sanders

My favorite vegetable is broccoli. I use it so often for cooking and it’s high in protein, fiber and other nutrients.

FASHION COPY EDITOR

Katherine Winkleman

Carrots, raw or roasted.

WELLNESS EDITOR

Chloe Gust

WELLNESS DESIGNER

Vaughn McDougall

The controversial-but-ever-delicious brussel sprout!

WELLNESS COPY EDITOR

Zoë Vincent

Red peppers / bell peppers / capsicums (choose your favourite wording). They’re so versatile and cheerful.

Sabrina Greene (Chiba Prefecture)

It’s your first day on the job as an Assistant Language Teacher. You show up to school eager to get to know your students, but there’s a catch—you don’t speak much Japanese, and they only know basic English phrases. Their expectant eyes meet yours, and you think, “How in the world am I going to connect with these kids?”

Rachel Titshaw has a unique answer to this question. She noticed the widespread popularity of anime like Spy Family among her students and immediately put it to use. “I wore Spy Family [character] Anya’s little hair buns every time I had a new class because I couldn’t express to [my students] in words that I was nothing to be feared,” she says.

A third-year ALT in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Rachel has a reputation among her students and community for her creative, eye-catching style. Sometimes she sports bright statement pieces thrifted from Off House, and other days she repurposes shirts as skirts. As she puts it, each outfit has its own personality, and her style depends on the day.

“My fashion inspiration comes from my interests, like anime and K-pop,” she explains.

“Megan Thee Stallion and Key [from K-pop group SHINee] are my icons right now.”

Rachel began her fashion journey as a junior high schooler. In elementary school, she tended to conform, especially during the one year she had to wear a uniform in private school. But by the time she hit middle school, she found it tiring to dull herself down. “I decided it was worth the payout to be crazy sometimes.” She would wear accessories from Party City, a party supply store, and experiment with extreme styles.

“Ithelpedmerealize thatwecanembrace thethingsthat makeusdifferent andexternalizethem withclothes.It helpedmefindmy peoplefaster.”

Many years later, Rachel had a similar experience upon arriving in Japan. Her predecessor, who moved on to become a CIR (Coordinator of International Relations), was a fantastic Japanese speaker whose manner and fashion fit seamlessly into the Japanese workplace. Rachel, still early in her language journey, felt the pressure to live up to her new environment’s expectations. However, she decided to take a risk and dress in a way that felt true to herself.

Unfortunately, not all ALTs have the freedom to play around with style at work. Dress codes throughout Japan are famously strict, and depending on the school, these rules can apply to teachers too. One ALT in 2020 aimed to teach her students about the significance of hoop earrings in Latin American cultures, but her Board of Education forbade her from wearing them to school.¹

Others are told to take out their piercings, change their hair, or wear formal business attire every day. Ultimately, it’s up to each ALT to exercise their best judgement around clothing in the workplace.

As one of the most visibly foreign people in her rural town, Rachel leans into the spectacle. “If people are going to stare at me, I’m going to give them something to stare at. It’s better than cowering away. It has really built my confidence,” she explains, grinning.

Luckily, the risk paid off for Rachel. “Why do you look like a boy today?” Rachel’s elementary school students would ask her when she wore more masculine clothes. She relished the opportunity to start a conversation about gender and fashion. “I’ll point at my sweater and ask them, ‘Is this a boy?’ and they kind of chuckle. It’s a lighthearted way of showing them that clothing has no gender.”

Rachel’s piercings also became a hot topic. Though her students worried she’d get in trouble for them, they quickly became normalized. Rachel saw this as an important cultural exchange moment. Though still relatively rare in Japan, “[having piercings] is normal in a lot of places.”

Fashion is powerful to her inside and outside the classroom, because it “combines history with the story of an individual person. It’s a way to experience yourself and your background.”

She wants to inspire her students to develop this aspect of their identity, especially in a place with such a rich and storied fashion history, stretching from kimono to 90’s

“I don’t care if it’s considered tacky as long as it’s something I enjoy,” she says. “Cringe culture is dead.”

Much to the contrary, she found the student and her mom waiting for her. The student handed her an envelope. Inside was an illustration of Rachel and Anya in a lovingly made paper frame, along with a message that read, “To Rachel sensei: I like Anya, too! Thank you for coming to X Elementary School!” To this day, this remains one of Rachel’s favorite memories. “I’ve always loved the kids, but it was the first time I realized I meant something to them, too. It was so meaningful—and all because I wore my little Anya buns around.”

To Rachel, few things exemplify the communicative power of clothing better than an encounter she had with a student. One day, Rachel was wearing her Anya buns at the mall when she spotted one of her students sporting an Anya t-shirt. The student and her mom came up and asked to take a picture together; Rachel happily obliged. A few weeks later, a knock came on the teachers’ room door—for the first time, someone had come to call for her. Rachel went out with trepidation, worried she was in trouble.

Sabrina Greene is the fashion editor of CONNECT magazine.

1) Sora News 24

Many people only have a vague idea of what life in the Japanese countryside looks like. They may imagine a slower pace of life, intimate communities, and affordable rent prices. There are vegetables for days. It can be idyllic, but rural Japan also suffers from shuttered shops, canceled train lines, closed kindergartens, and abandoned infrastructure. The population is aging, and young people are moving to urban areas.

For Yukiya Mogami, owner and hairstylist at Fumi Salon, moving back home from Chiba City to Yokoshiba Hikari was jarring, even thirty years ago. “In Chiba City, my clients were super fashionable, but out in the countryside, they were mostly older women and farmers,” Yukiya says, laughing. “They asked for old styles—perms so tight, they looked like afros.” It was a huge change from what Yukiya was used to, especially in the early days of his career.

When he was 18 years old, Yukiya left Japan to study in Canada. It’s a story more common now but still fairly rare in the 1980s, especially for kids from rural areas. First he headed for California, dreaming of a career in the movie industry. When that proved to be unrealistic, he enrolled at a school in Vancouver. “The school’s concept was that Japanese and Canadian students could study together,” he explains. “But in reality, the tuition was high, so there weren’t many Canadian students.” Hoping to get more immersive English practice, Yukiya signed on as an apprentice at a hair salon on top of his usual studies.

It was an unpaid position, but Yukiya says it changed the course of his life. “The salon owners were so kind, especially my teacher. I decided to become a hairstylist because of them.” The time he spent with his host family also made a deep impact: they were an average family with young children, and through them, Yukiya was able to experience family dinners, cozy holidays, and toast-and-coffee weekday mornings—a side of Canada he would have never seen as a tourist.

Outside of his formal education, Yukiya had plenty of experiences in Canada in the ’80s that still inform his aesthetics today. With leather jackets, tight flared jeans, and leather boots, his everyday fashion evokes images of mountain motorcycle rides and iconic classic rock concerts. Particularly memorable is Brian Adams’ show in a small livehouse, where Yukiya was front row in the audience. “I kept shouting, ‘Do “Summer of ‘69!”’ And finally, when he played it, he dedicated it to me.” Brian Adams’ autograph still sits proudly in the corner of Fumi Salon.

Ultimately, Yukiya returned to Japan due to visa troubles, but his hairstyling education continued. He secured an apprenticeship at the Chiba City location of Mod’s Hair, a Parisian salon founded in 1968 and regularly featured in magazines like Elle, Marie Claire, and Vogue.

He trained there for three years, learning how to cut all the classic styles. Though the pay was low, he soon worked his way up and gathered a roster of over a hundred regular clients. “The first client I ever had at Mod’s was a woman from rural Chiba who worked in Tokyo,” recalls Yukiya.

“She would stop by on her way home. I remember feeling such regret after she paid and left—all I could see were the flaws of my own work. I told her this story recently, and she said ‘I liked your haircut, which is why I’m still here!’”

Yukiya is still in touch with his host family and hairdressing teacher today. “Their kindness affected me a lot. It made me want to keep up my English skills and pay it forward to foreign people in Japan.” And so he has. Around 2000, Yukiya joined the neighboring town’s English circle, an adult language group that still meets twice monthly to this day.

“There was an Assistant Language Teacher from Hawai’i who came to my salon for a haircut. He couldn’t speak Japanese, so he was so happy to be able to speak English with me.” They bonded over their shared interest in surfing, and the ALT invited him to join the English circle. Ten years later, Yukiya became the group’s organizer, reserving the meeting space and planning yearend parties. He also maintains a connection with the town’s current ALTs.

These days, Yukiya is back to the basics—he hasn’t pulled his red python skin boots out of the closet in a while, opting for a more classic look: jeans, white shirt, leather jacket, and pointy-toed boots. And the older clientele don’t bore him in the way they used to. “At some point, I began to enjoy talking to them,” he says. “There’s a lot they can teach me, even at my age.”

Yukiya thinks a lot about the future of Fumi Salon. The government has considered widening the road in front of the salon; if it does so, Fumi Salon will have to shutter to make way for construction. No such plans have materialized yet, and so Yukiya tentatively plans to stay open another 15 years, until he’s 70. After that, he plans to reduce his hours to part time—to keep his mind and his hands busy in old age. With no kids to take over for him, Fumi Salon will eventually close after more than 50 years in business.

To quote the wise words of Smash Mouth, “The years keep coming and they don’t stop coming.” People get older; things change. The cities may be exciting centers of industry, but the countryside is far from barren, nor is it always isolated, as people seek connection wherever they are. The stories found in hair salons, family-owned cafes, and old homes are vibrant, diverse, and often surprisingly international. As the older population slowly disappears, it is the responsibility of younger generations to listen to their stories and remember for them.

Sabrina Greene is the fashion editor of CONNECT

the eternal battle between Montrealstyle and New York-style bagels, she firmly believes they’re both the winner.

We spend a lot of time getting to know every single student in the school.

Skyoyu in Japanese) hold a unique position within the Japanese school system. They are one of the few staff members whose work involves interacting with the entire student body.

Though they are called nurses, and do many important medical tasks, they also have a duty to care for the mental health and health education of their students. Despite being so involved in everyday school operations, the exact breadth of their duties and responsibilities can be difficult to pin down for people who didn’t grow up in the Japanese school system.

Fortunately, Kazuyo, a Kyoto-based elementary school nurse with over 25 years on the job, took the time to answer some questions from CONNECT to resolve some of the burning questions you may have.

CONNECT: Why did you want to become a school nurse?

KAZUYO: Originally, my plan was to become a pharmacist because I enjoy helping people feel better. But during schooling, I was able to work a job with children and decided that I wanted to work with children in the future.

average day look like?

KAZUYO: I collect the health check sheet from outside each classroom. Then I check to see which students are sick, especially with the flu and COVID. Afterwards, I am in the nurse’s office to help students that have had an injury, headache, stomachache, etc.

When we don’t have any students in the office, we start to make and decorate the inside and outside of the nurses’ office with interactive health information.

The children really love it and it gets them to learn about different health-related topics. For example, we currently have some optical illusion decorations to teach students about perception.

CONNECT: What are some special tasks or duties that school nurses must do?

KAZUYO: I can perform duties that some other teachers cannot, such as dealing with blood, as well as injuries to the eyes and head. Along with the school administration, I help when deciding whether or not a student requires to go to the hospital, ER, etc.

CONNECT: What is something people might not know about school nurses?

KAZUYO: We spend a lot of time getting to know every single student in the school, their health situation and homelife as well.

CONNECT: What do you think affects the students you see the most?

KAZUYO: We mostly see injuries to the hands and feet, students with headaches and/or stomachaches.

CONNECT: Do you notice any differences in the students from when you started your position to now?

KAZUYO: I started working in a different area in Kyoto than my current school, but the students are still doing their best in the same way they were 25 years ago!

Chloe Gust is a former Hiroshima ALT. She would like to use this space to thank her school nurses for always giving her medication and sympathy when she had bad cramps. She couldn’t have made it through without them.

Taylor Hamada, a former JET Program ALT, is a Kyoto-based teacher supporting students with non-Japanese roots. She spends her free time buried in books, exploring Japan, and farming in Stardew Valley. She shares her love for reading with fellow bookworms through content on YouTube and Instagram. Check out her socials: @taylorofcontents

The students are still doing their best in the same way they were 25 years ago!

CONNECT: Is there anything you would want to change about your position?

KAZUYO: I wouldn’t change anything at all about my position.

CONNECT: What is your favourite part of your job?

KAZUYO: My favorite thing about this job is seeing my students who have graduated and are now working and have families of their own. Telling me about their lives makes me happy and I understand that they're still doing their best in life.

Yoygo kyoyu like Kazuyo are the hearts of their schools, providing support for generations of students—physically, mentally, and emotionally. Through actions big and small, their support creates an environment where students can grow.

LANGUAGE EDITOR

Kalista Pattison

I don’t believe in vegetables. Something I learned while getting my degree in biology is that botanically speaking vegetables don’t exist. Garlic is a bulb, a potato is a tuber, a pumpkin is a fruit, spinach is a leaf, a carrot is a root, and so on…

LANGUAGE DESIGNER

Jessica Barton Pumpkin or sweet potatoes.

LANGUAGE COPY EDITOR

Aidan Koch

Spinach–great by itself, even better in a salad or recipe!

CAREERS EDITOR

Kimberly Matsuno

It’s not so much a vegetable as it is… well… a leaf, but lately I’ve been in love with shiso. It’s such an easy plant to grow and adds a wonderful flavor to so many dishes.

CAREERS DESIGNER

Renee Stinson

Broccoli! How is it that it's stereotyped as the gross vegetable kids hate in cartoons?

CAREERS COPY EDITOR

Katherine Winkleman

Carrots, raw or roasted.

Brooklyn Vander Wel (Hokkaido)

“As a kid, I truly believed if I said a Japanese word with a different intonation then I’d be speaking a different language,” Fukiko Takeyama laughs. With more than two decades of experience teaching English to Japanese students, Fukiko finds a lot of humor in the erroneous logic of her past. As an example, she cites the Japanese word for apple, ringo. If one stretches out the normally crisp two syllables into three, it would certainly sound different. Yet a ringo is still a ringo, no matter how it’s sliced. When Fukiko learned what the actual English word for ringo was, she was so stunned she needed to learn more. For a young girl who spent her 1970s childhood on her beloved but small island of Amami Ōshima, about a forty-minute plane ride north of Okinawa, English has opened many new possibilities in Fukiko’s life.

At just twelve years old, Fukiko went to boarding school at Immaculate Heart Girls School in Kagoshima, located in the southern part of Kyushu, one of Japan’s main islands. She was amazed at the older girls in her school who learned subjects such as English, ballet, and piano with equal skill. Despite average English grades in junior high, Fukiko was determined to visit the United States. In 1982, that dream came true during the summer of her first year in high school when she participated in a one-month homestay in the small town of Duvall, Washington, United States. Together with about thirty other participants in the program, Fukiko studied American culture in the mornings and did activities in the afternoon, like visiting a firefighter’s station or the local farmer’s market. Using every English skill at her disposal, Fukiko wasn’t afraid to ask questions or make it known when she needed phrases to be repeated.

This proactive approach paid off, as there were many friends to be had in everyday places like the grocery store, post office, and church. Elated she could make friends using another language, upon returning to Kagoshima she continued to study English.

“As high school graduation neared,” Fukiko reflects, “I got hooked with the American education system. They make you think, not like in Japan. Instead of saying ‘memorize lines one to ten, repeat after me’, in America it was more like, ‘how do you feel, what do you think?’” Motivated to improve her English and critical thinking skills, Fukiko again set her sights on studying abroad. First she spent two years at Immaculate Heart’s community college, then in 1987 she moved to Spokane, Washington to attend Gonzaga University. When she first arrived on campus, she was shocked she could hardly understand what was going on considering she had been the top English student back at community college. Determined to adjust, three and a half years later she earned her hardwon degree in speech communication and journalism.

With that American degree in her back pocket, Fukiko returned to Japan in 1991 to enter the workforce. Her first job was to work for the government in Tokyo as a secretary of the International Affairs Department. Of course, to nab the job she needed to take tests, concluding with an all-English interview. In her new position, Fukiko’s studying paid off: people from all over the world like Switzerland, Germany, and the Philippines wanted to meet with her bosses, and she was there to translate. While she learned a lot, the job required a lot of overtime, with eight-hour days often stretching to twelve. After four enjoyable but hectic years in the big city, it was time to go home.

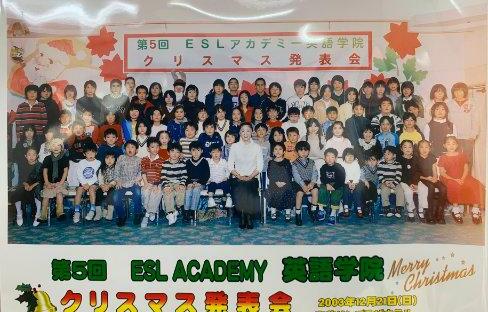

Back in Amami, life in her thirties was a blur. In 1997 she started her own English tutoring business, ESL Academy, and her daughter came the next year. Only two boys attended her initial class, but the next week those students brought two of their friends, and the cycle continued. At its peak, around 90 students came to her classes.

However, it became too much work for one person, and eventually Fukiko stopped tutoring high school students. Many of them wanted to go to medical school, which made their entrance exams tough to prepare for. However, that didn’t mean she was completely removed from the health field. She taught English at Amami Nursing and Welfare Community College twice a week.

At ESL Academy, she tutored students from kindergarten to junior high every weekday from 3:00 to 10:30 PM. Yet it didn’t end there, as students often stayed until midnight to ask questions and receive detailed feedback. During summer break, Fukiko even offered intensive classes but kept one special week to herself to spend time with her daughter.

Years of teaching comes with years of observations, so Fukiko shares a few about teaching Japanese speakers English. “It’s one thing to teach them how to score well on tests. It’s another thing to actually teach them how to communicate in English. The Japanese education system makes it so there isn’t enough time to teach both.” Despite not being able to teach everything she would have liked, Fukiko encouraged her students to not be afraid to speak English. She introduced English books, songs, and videos to support their studies. Impressively her students have gone on to careers in various fields such as aviation, medicine, education, finance, and entertainment. Some even work overseas for companies such as Mitsubishi.

Like her time in Tokyo, this good thing came to an end. In 2014 she closed her academy to accompany her daughter to first Auckland, New Zealand for junior high, then Bothell, Washington for high school.

When asked if she feels like she is still learning English, Fukiko smiles. “Of course! It’s so tiring when people don’t know any Japanese and I have to use English all of the time.” She adds, “I do love English. Without it, my way of thinking would be so much narrower. I’m very blessed to have come this far.” After seeing her daughter graduate high school, Fukiko has once again returned home to her favorite place on Earth: Amami. This time she’s taking it easy, much easier than in her thirties—after all, hard work makes paradise that much sweeter.

Brooklyn Vander Wel is a first-year JET participant who recently saw a whale shark for the first time in Okinawa. The rating: 10/10 majestic. When they’re not scouting for the best conveyor belt sushi joints to write home about, they like to read and write as part of a healthy diet.

Alice Polaschek (Kyoto)

When I arrived in Japan, kanji was still a mystery to me. Menus were a swarm of unfamiliar shapes and lines on a page. Thankfully, my local family restaurant had photos of every menu item—at least I could point to something! Despite the language barrier, I could communicate what I wanted to eat! Here, functional communication enabled me to order my food.

The first part of this series, “Laying the Foundation,” introduced speech, language, and their relationships to English language classrooms. Now, we’re going to delve into teaching students to get messages across, no matter how “perfect” their grammar is and even if they can’t find the right words. Functional communication is the goal of many speech-language therapy interventions and should be a goal for language learning too—meaning this is applicable for your own language studies!

Functional communication is all about using the tools you already have to get a message across. Speech-language therapists (SLTs) don’t always focus on spoken language when helping students communicate. For many students, speaking articulately is a challenge, and the focus needs to shift to helping them get messages across in whatever form they can. It requires flexibility and some resourcefulness on the part of the speech-language therapist. Throughout an assessment, an SLT might notice that a child is communicating primarily through gestures and identify ways to extend these skills through adapted sign language.

SLTs have a few different tools for this, which fall under the Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) banner. You’re probably already using AAC! It’s used instead of spoken language or to enhance your message when you can’t convey things through speech.

The most recognizable example of alternative communication is Stephen Hawking and his eyecontrolled computer screen. A range of apps, including text-to-speech and digital communication boards have also been developed. Hightech tools like these are used in language learning too such as Google Lens, translators, and online dictionaries.

There are also “low-tech” or “notech” devices that are more accessible and customizable. Notech includes drawing, adapted sign language, gestures, facial expressions, and body language. All you need is your body, a chalkboard, and some chalk! In part one, we discussed how these can enhance what you’re saying to your class, but students can use them in conversations with each other too!

A common low-tech tool SLTs recommend is a communication board: an array of pictures and words a student can point to. The words on these boards are generally core words like “good”, “want”, “get”, “same” and “on” which can be used in many different situations. They are super flexible and make up 80% of what people say in everyday life! However, any words can go on a communication board. You and your students could create a communication board to act as a vocabulary prompt during conversation activities. You can pick the topic together and select words to put on the board! It could also be a vocabulary prompt for your students before getting into a conversation topic. Other low-tech options include sequences of pictures to give instructions, share schedules, or offer choices.

Consider why humans communicate in the first place. Often it is transactional—“I need this and you’ll give it to me,”—but it’s also about connecting with others by sharing stories, opinions, and information. In most settings, these things aren’t communicated in perfectly grammatical and clearly articulated sentences, yet no one bats an eyelid.

Often, the focus of English classes is learning the sentence patterns and vocabulary that will be on the next exam instead of using the language to communicate. When incorporating functional communication into English teaching, the goal is to talk about things that matter to your students!

As you talk to your students, show them ways to communicate without words or navigate forgetting previously learned words or grammar structures. These strategies include:

Circumlocution, or talking around a word. You could say, “It’s that hot brown drink,” if you forgot the word for coffee.

Acting something out or gesturing towards an object.

Drawing a picture or showing an image on a device. Use whatever is available to show, rather than tell. Image searches are great for this as you can build out the conversation along with the specific type of coffee you want to show them.

If a sentence is hard to form, say a few keywords together. “Want drink coffee” gets the job done even if there are missing words.

Speaking is daunting for any language learner, but showing your students that they can have a back-and-forth interaction in English, even if they forget words or miss key grammatical concepts, is the most motivating thing you can offer as an educator. It might take your students some time to practice strategies and use them effectively, but giving them little opportunities for conversation every day will help them get there.

You can use these strategies in your Japanese learning too. Start using sentences that get the job done rather than fretting about perfect grammar. Pull up a picture on your phone rather than the translation app. As with your students, it’ll take practice, but connecting with others through communication will become addicting.

Alice Polaschek was an ALT in Miyazu, Kyoto. She spent her year in Japan finding new favorite foods and walking along Northern Kyoto beaches. She returned to her hometown, Wellington, New Zealand, and job as a speech-language therapist in August 2024. When she isn’t working, she is probably knitting, reading, attending pilates classes, or trying to recreate her favorite Japanese foods with Western ingredients.

COMMUNITY EDITOR

Tori Bender

I could eat sweet potatoes every day!

COMMUNITY DESIGNER

Vaughn McDougall

The controversial-but-everdelicious brussel sprout!

COMMUNITY COPY EDITOR

Aidan Koch

Spinach–great by itself, even better in a salad or recipe!

TRAVEL EDITOR

Jon Solmundson

The onion is the king of all vegetables. How can one humble orb contain such a diversity of flavour? Mouthtingling crunch, subtle umami, or caramel-sweet char - the choice is yours.

TRAVEL DESIGNER

Jessica Barton Pumpkin or sweet potatoes.

TRAVEL COPY EDITOR

Kaitlin Stanton

Tomatoes (I know I know, they’re technically a fruit) are so versatile and have made their way into so many cultural cuisines.

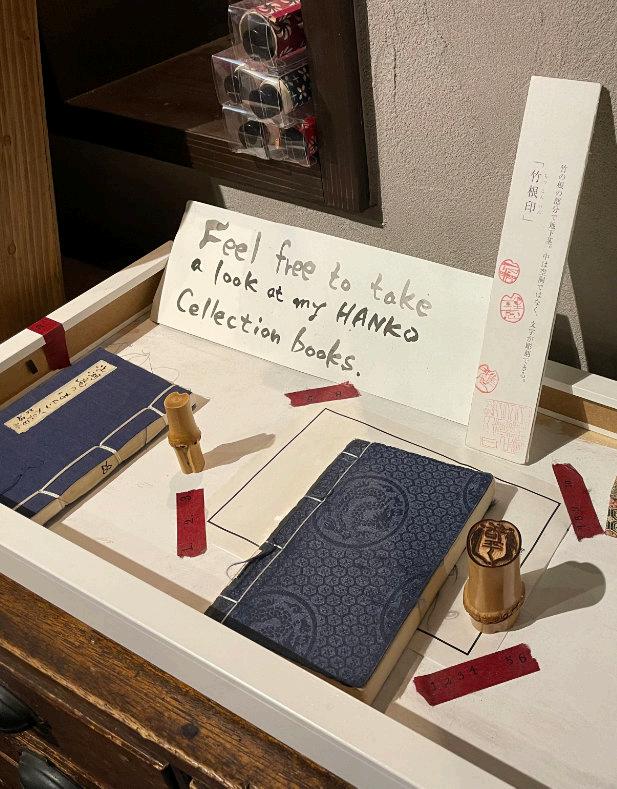

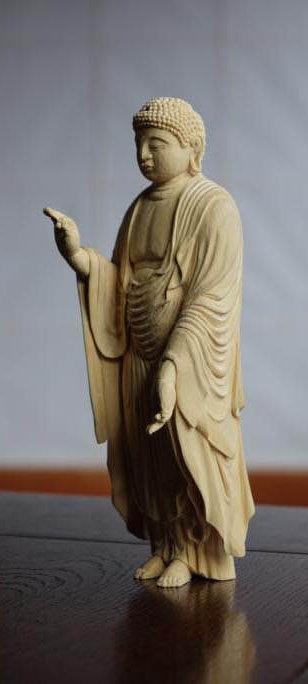

Hanz Georg Weiz is carving an unusual chess piece.

He’s been commissioned to make a whole set for someone on the other side of the world. He’s currently finishing up the first piece: the king. Only this king is a traditional Japanese dragon. This piece alone, each line delicately and painstakingly carved by hand, has taken him nearly a month. In the soft light, shadows ease their way into the grooves, giving the piece an unearthly depth.

Georg Weiz, more commonly known as Asaya, has been living in a small town in Toyama called Inami for a little over a year, studying under a series of master woodcarvers. He’s the first European to become an official apprentice to the woodcarvers in Inami, worldrenowned for their style and skill.

He says, “There’s such richness here in Inami. It’s so inspiring. The first time I came here I was just amazed at how beautiful the town is. People have been so welcoming and so supportive here. It’s been incredible.”

In the first decade of the 1800s, Inami was forever changed by a craftsman from Kyoto.

He was commissioned to rebuild the local temple, Zuisenji, after a fire and took several families from the nearby village as apprentices.

When he was recalled to Kyoto, they carried on using his techniques and the town flourished as part of the wealthy Kaga domain.

Walking through the town today, there are beautiful carvings everywhere you look—ranma, decorative panels that hang above doors, lifelike carvings of cats hidden around the village as a charming scavenger hunt. Even the temple’s “take off your shoes” and “no smoking” signs are beautiful wood carvings.

Recent years have been less kind to Inami. Less than 50 years ago, more than 300 master woodcarvers lived in Inami. Today, though, there are just shy of 150. The average age of the woodcarvers is 70. Asaya says there’s a genuine fear that, one day, the craft could be lost.

There’s such richness here in Inami. It’s so inspiring.

by Asaya

“Time is running out. This skill and knowledge would be very sad if it gets lost. I hope it can get passed on. But there are more people coming and I think, if the community here starts seeing that, it will open up to foreigners who want to study here. There will be solutions that the community can present.”

His own story has been a whirlwind. Originally from Germany, Asaya preferred working with his hands to academia, eventually moving to Sweden to study woodcarving.

Once he’d finished, he moved again to Mexico. It was there he first learned about Inami and the unique woodcarving style. He set off to Japan with one goal: be accepted as an apprentice in the town.

“In Mexico, I was feeling that I had learned what I had gone to learn. I got interested in Japanese woodcarving after seeing some pictures online and I heard about this village with 200 woodcarvers in it. I was blown away and couldn’t understand how they could make these intricate works. I decided I have to come here.”

Searching through social media, he found a woman who had tagged herself in Inami and messaged her. When the conversation fizzled out, Asaya was left with no choice but to go to Inami himself and try to find somebody.

He was on the bus to the town when she messaged back: A friend of a friend is a woodcarver and when would be good to meet?

“I said I’m on the bus now on my way to Inami, so now would be great! She said OK. Then I met the head of the woodcarving cooperative and my first teacher, Toshida-sensei.

“We met in the Woodcarving Museum and we talked. After a bit, they said they’d accept me as an apprentice. I’m not sure why they accepted me. Maybe they saw I was really curious and interested.”

Typically, apprentices study under one master for five years, living under the same roof, eating the same meals, and earning enough money to gradually build up their own set of tools.

The apprenticeship ends with a “payback” year—working mostly for free under their master to pay back the cost of the apprenticeship. In his time with the different teachers, done in modern times because of the lack of apprentices, Asaya has made a wide variety of carvings.

During his time in the village, Asaya started an Instagram documenting his woodcarving journey and has amassed thousands of followers. He says they’ve been really encouraging. His passion is clear to see.

“The woodcarving itself is so fulfilling. The learning here is so fulfilling, it gives me so much. And the patience is something that I’m really starting to enjoy learning.

At the beginning, it was difficult for me to work for so many hours on the same piece but now I’m starting to enjoy the patience that it takes. There’s something here in Japan that makes it really enjoyable. To me, it’s like a spiritual practice. Woodcarving becomes a practice of growing yourself as a person.”

Mike Taylor is a JET alumnus based in Kanazawa, Ishikawa. Originally from Scotland, he spends most of his time longing for Irn Bru, Tunnock’s tea cakes, and a good breakfast with plenty of baked beans.

Asaya’s Instagram

Tori Bender (Hyogo) interviewing Sophie McCarthy (Tokyo)

Making new friends is a challenge that many foreign residents in Japan face when trying to integrate into their new communities.

Various factors may add to the difficulties: population density, language barriers, a pandemic—and in Sophie McCarthy’s case, moving to a vast city like Tokyo presented all three.

Amongst the densely populated and seemingly endless sprawl, Sophie stumbled upon a local book club, connecting with others who shared her love of reading.

Koen Book Club is a group that meets in parks around Tokyo to discuss books chosen by members. While living in Tokyo, the club became a special community and space for Sophie to socialize and step out of her comfort zone.

Can you tell me a bit about your move to Tokyo and your search for community in such a big city?

When I moved to Tokyo in 2022, I faced the challenge of finding meaningful connections in a sprawling city. The pandemic had fundamentally changed

how people interact, leaving many of us feeling isolated.

Although Tokyo is the largest city in the world, its sheer size and fast-paced, transient population can make it surprisingly lonely.

Unlike the structured support of JET, I was now navigating on my own, searching for a sense of community in a culture and language that didn’t always align with my own.

What drew you to books and reading while living in Tokyo?

Books became a sanctuary for me during that time. They offered a sense of productivity and escape when the social landscape of Tokyo felt overwhelming. Reading also gave me something to focus on while staying home, allowing me to find comfort and reflection in solitude.

That first meeting set the tone for my experience— welcoming, engaging, and filled with new perspectives.

Through social media, I noticed a friend attending a monthly Tokyo book club called “Koen Book Club.” The group met in different parks to discuss books chosen by members. It seemed like the perfect opportunity to step beyond my comfort zone while doing something I already loved. At the time, I was reading so much but had no outlet to share my thoughts and opinions.

I was dying to discuss the books I loved with others who shared the same passion for reading. Nervously, I decided to attend my first meeting, comforted by the thought that even if conversation lagged, we’d always have the book to fall back on.

I was pleasantly surprised by how easily the conversation flowed. Everyone shared their thoughts openly, and it felt natural to connect through the book. That first meeting set the tone for my experience—welcoming, engaging, and filled with new perspectives.

The atmosphere was consistently warm and inviting at each and every meeting, which is why I hardly missed any since that first one.

It’s a space where I felt both challenged and supported in my opinions, making it something I looked forward to every month.

How has being part of a local book club in Tokyo affected your sense of community?

The book club provided me with a sense of belonging that I didn’t realize I was missing. It became more than just a group to discuss books—it was a space of kindness and mutual support.

Meeting regularly with the same people created bonds that extended beyond the club, making Tokyo feel less overwhelming and more like home.

What do you think makes this book club unique compared to others in Tokyo?

The club’s flexibility and warmth stand out. Members come from diverse backgrounds, which makes every discussion rich and thought-provoking. Everyone brings a mature and nuanced approach to our conversations, which is refreshing in the age of social media, where online discussions often veer into volatility.

Beyond the discussions, members also support each other’s individual endeavors, showing up for events or projects outside the club. The informal, park-based gatherings feel approachable, fostering connections naturally rather than formally. It’s a space where ideas are exchanged openly and respectfully, and where mutual support strengthens the sense of community, making it truly unique and valuable.

What is Koen Book Club up to now?

The club continues to meet monthly, with a steady mix of regulars and newcomers. During the colder months, they find cozy indoor places to meet, which adds a nice mix-up to the usual format.

Their next book is Human Acts by Han Kang, who just won the Nobel Prize for Literature. Even though I’ve moved on, I’ll continue to look to their Instagram for their monthly book choices, using them as recommendations for my own reading. It’s exciting to know the group is thriving and continuing to offer fresh literary inspiration.

Is there anything you will be taking away from your experience with the club as you move into a new stage of life?

I’ve learned the importance of stepping out of my comfort zone to find community. Joining the book club reminded me of the power of small connections and the impact they can have on our lives.

As I return to the U.S., I’ll carry the friendships and lessons from this experience, along with a bit more courage to seek out meaningful connections wherever life takes me.

Tori Bender is a teacher, artist, and editor for CONNECT based in Hyogo Prefecture. She loves mountains, rivers, and the Japanese countryside. In her free time, she likes to paint, skateboard, and watch movies. She is happiest around close friends and with her mischievous orange cat, Sora. Tori’s Instagram

Sophie McCarthy was a JET for four years in Kobe, Hyogo Prefecture (2018-2022). She now lives in Tokyo. In her free time, she enjoys reading, visiting kissaten, and practicing film photography. Check out her photos on Instagram: @filmbysophie

Turn your JET experience into a fulfilling career.