lit t l e b r o wn

Nut

by Mary Auld

by Mary Auld

Here is a tall Brazil nut tree.

It is one of the tallest and oldest trees growing in the rainforests of South America.

And here is a large, hard fruit falling from its branches.

It weighs around 5 lbs and measures about 6 inches across.

Here is the fruit on the forest floor. Safe inside are 20 wedge-shaped nuts. They fit together snugly, like orange segments.

These little brown nuts are Brazil nuts. And one of them is me.

Here is the agouti that opened the hard fruit. It’s just about the only animal that can!

The agouti is a rodent, like a guinea pig but with longer legs. It lives and feeds on the rainforest floor.

Brazil nuts are full of energy. They make a good meal for an agouti.

The agouti uses its strong, sharp teeth to open the hard fruit and the Brazil nuts inside. There could be 8 to 24 nuts.

The agouti feasts on the tasty nuts but can’t eat them all. It buries me under the ground for later.

An agouti sits on its hind legs to eat. It holds the nut in its front paws to gnaw on it.

Like a squirrel, it makes stores of nuts to eat later.

Here I am under the ground, covered with leaves.

The agouti has forgotten where I am. It is the perfect place for me to wait . . . and grow . . .

A Brazil nut is a seed. It grows into a tree if it is buried away from its parent plant or other big trees.

It may take a year for a seed to germinate (begin to grow). It waits for the right moment, when the soil is damp and there is enough sunlight.

Leaves fall from rainforest trees all the time. The leaf litter rots into the soil and its goodness helps seeds grow.

Above me, an empty Brazil nut fruit has filled with rainwater. It has become a home for tadpoles.

The Brazil-nut poison frog is only around 0.8 inches long. It is a tree frog and lives among the leaves.

The female lays two to six eggs on the ground and the male guards them.

When a tadpole hatches, its father carries it to the Brazil nut case pond. Here the tadpole feeds in safety and grows into a frog.

Here are my first roots. They reach out and down into the ground. I am growing!

Inside each Brazil nut is a tiny new plant surrounded by a store of food, rich in energy. It needs this energy to germinate.

When the time is right, the plant’s root pushes out of the seed case down into the ground.

The root has tiny hairs on it. These take in water and goodness, called nutrients, from the soil.

Here is my shoot, reaching up toward the sky.

My two seed leaves open up and I can make my own food. I am a seedling!

Plants make their own food in their green leaves. This is called photosynthesis.

leaves

The seedling’s leaves take the gas carbon dioxide from the air.

Oxygen, the gas we breathe, passes out of the leaves into the air.

shoot

Sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide turn into sugars and oxygen in the leaves.

The sugars are the plant’s food, its energy to live and grow.

UNDERSTORY

Here I am growing through the rainforest. Can you see a sloth in my branches? I am 50 years old now and my straight trunk reaches up through the understory.

In the canopy, animals and birds feast on the fruit of the trees.

Look at my parent tree, high in the emergent layer. One day, I’ll be as tall as it is, with my branches spread out above the forest.

Brazil nut trees are rainforest giants. They can grow up to 160 feet tall. Their trunks can measure more than 6.5 feet across.

Here I am fully grown. My flowers bloom among my leaves and harpy eagles have built their nest in my branches. Their chick is safe up here!

Harpy eagles mate for life. They raise a single chick every two or three years. They feed it for over a year until it is ready to leave the nest.

The eagles perch on high branches to look for prey, which includes monkeys, sloths, and lizards. They catch them with their huge talons, the largest of any eagle.

Can you see a beautiful orchid growing on the tree below me? Its scented flowers attract lots of bees, and this helps me . . .

Male orchid bees feed on the orchid’s pollen. As they feed, they pick up the scent of the flowers.

The scent of the males attracts females, and it’s the females that I need.

Here is a cluster of my flowers.

The waxy yellow petals hide sweet nectar— food for a female bee.

The female orchid bee is larger than the male. Only she is strong enough to push into the flower.

A Brazil nut tree flower is nearly 1.6 inches wide. It has six petals and a protective hood at its center. Under this are stamens, which produce pollen. Inside is a stigma and a nectar store.

As the females fly from tree to tree, they take pollen from the flowers on their legs and furry bodies.

The bee is covered with pollen from another tree. The flower’s shape forces the bee deep inside it to feed.

The bee’s long tongue can reach down into the center of the flower to lap up the nectar—a sugary, rich liquid.

The pollen sticks to the stigma. The flower has been pollinated.

Here is a bee, come to feast on my flower’s nectar. She will pollinate the flower so it can become a fruit.

Here are my first fruits!

Thank you, bees, for pollinating my flowers. Thank you, agoutis, for planting me as a little brown nut. Now I have made my own fruits, full of Brazil nuts.

The center of the pollinated Brazil nut flower grows into the tree’s fruit. It takes about 14 months.

A large Brazil nut tree can produce over 300 fruits a year—that’s around 6,000 nuts.

Scattered around the Amazon, there are Brazil

nut trees like me, their branches heavy with fruit. The rainforest grows around the huge Amazon River and the many other smaller rivers that flow into it.

THEWORLD

The country of Brazil gives the Brazil nut tree its name, and many grow there. Peru and Bolivia also have a lot of Brazil nut trees.

Look out below!

Here come my fruits.

Heavy rains from December to March loosen the ripe Brazil nut fruits from their stalks.

Agoutis arrive to gather my fruits. But what’s that noise?

The heavy fruits drop to the forest floor below. It’s a long way and the nuts can reach speeds of nearly 50 miles per hour. Animals below have to be careful.

The agoutis run and forget any nuts they have buried. Soon, another little brown nut will start to grow . . .

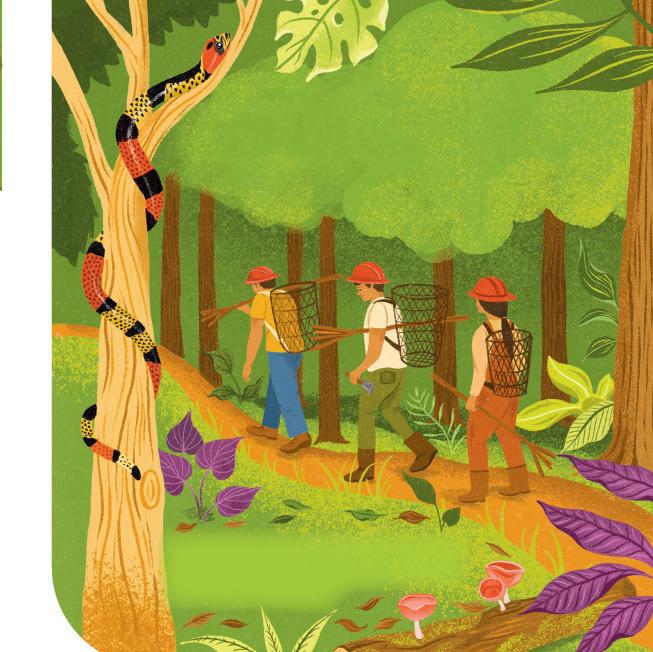

Here is a group of nut gatherers. People collect my fruit from the forest floor. Just like agoutis, humans love to eat Brazil nuts.

Rainforest people have harvested Brazil nuts for thousands of years—and still do today. Now they wear hard hats to protect their heads from falling nuts.

The nut gatherers are called castañeros. Every Brazil nut you eat has been collected by them.

They pile up the fruits and then cut them open with a strong knife. They carry huge bags of nuts on their backs to camps in the forest.

The nuts are collected from the camps to be shelled, dried, and sent—and eaten—all over the world.

Think how many Brazil nuts I will make in that time . . .

How many Brazil nut seedlings will grow from them . . .

How much oxygen my leaves will produce . . .

How many animals I will feed . . .

How many people will benefit from my fruits . . .

How many babies will grow up in my branches.

The castañeros help to protect me from illegal loggers who want to cut us down for timber. If protected, I will live for over 500 years.

START SMALL...

This is the life cycle that begins with a little brown nut and leads to a mature Brazil nut tree. A Brazil nut tree can live for over 500 years.

flower

AMAZON I-SPY

Find these rainforest animals somewhere in the book. Which layer of the forest do they live in?

root (6–24 months) seedling (2–10 years)

bee pollinates it agouti buries it

(inside a fruit)

sapling (10–100 years)

SOUTH A MERICA

mature tree (100+ years old)

rainbow macaw

mosquito giant millipede

fruit (14 months from pollination)

toucan

leafcutter ants

Brazil-nut poison frog

Brazil nut trees grow in all nine countries in which the Amazon rainforest lies. Brazil, Bolivia, and Peru harvest and export the most Brazil nuts to the rest of the world.

THINK BIG!

OLD GIANTS OF THE RAINFOREST

Some Brazil nut trees are thought to be over a thousand years old. That means they may have produced around 6,000,000 nuts in their lifetime!

RAINFORESTS HELP THE CLIMATE

Our Earth needs rainforests. They help to keep the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the air. Too much carbon dioxide contributes to climate change. They are important to the Earth’s water cycle, too, storing water and bringing rain to dry areas.

HEALTHY IN SMALL AMOUNTS

Brazil nuts are packed with energy and nutrients that help us fight disease and keep our hearts healthy. They are so full of goodness you should only eat one or two a day.

SUPERSTAR TREE

The Brazil nut tree is a rainforest superstar. It gives a home and food to all sorts of life, from agoutis to bees— and people. It is a reason to protect the rainforest and not cut it down.

Rainforests cover only 6% of the Earth’s surface but they are home to more than half of the world’s animal and plant species.

RAINFORESTS OF THE WORLD

assassin bug

squirrel monkey

There are rainforests all round the world, in hot regions where there is lots of rain. The Amazon rainforest is by far the largest. It is home to over three million different animals, plants, and fungi, some found nowhere else on Earth.

litt l e b r o wn Nut

This story starts with a large, hard fruit falling from the tallest tree in the rainforest. Safe inside is a little brown Brazil nut, a seed that needs a special animal to free it. Read about their relationship and how the little nut and the small, furry animal have a giant impact on the forest and the world. This story ends with a fold-out map.

Also Available