Journey to Mindfulness

FACILITATOR GUIDE TO ADOLESCENT MENTAL HEALTH

KAREGA CATHERINE, WANJIRU NGUNJU, LUCY FUTAKI

The First Step of a Lifelong Journey

Hi, welcome to the *Journey to Mindfulness*. This is an initiative of Akili Dada created to support adolescent girls to develop the skill to navigate their growth into wholesome individuals. At the beginning of the creation of this workbook, we spoke to a few girls in high school. We asked them about some of the things that affect their development psychologically and socially.

We talked about forming an identity, being part of a social community, recognizing our sexuality, dealing with feelings of anxiety, stress and depression, navigating through grief and self- harming behavior.

This book is not going to give you all of the answers you are looking for. It will assist you develop some life skills that will help you face life with confidence and pride. We also hope that even when you face challenges, you will use this book together with the many resources provided here.

More importantly, this book is not a substitute for professional help. Having a therapist and a trusted adult as a sounding board and guide is important.

Facilitator Guide

This facilitator guide was developed by Akili Dada as a tool for use when talking to adolescent girls about mental health and wellness. The contents of this guide are the sole responsibility of Akili Dada and do not necessarily reflect the views of *their partner organizations, the Ministry of Health of Kenya or the Government of Kenya*

Acknowledgements

This document has been developed by Akili Dada as a guide to be used when talking to adolescent girls about mental health and wellness. It is part of Akili Dada’s initiative to create a Mental Health Curriculum and draws from other adolescent health and youth-friendly publications including *List sources used here*

A team of consultants developed content relevant to the Kenyan context and in line with national guidelines for mental health and adolescent health. This team included:

Catherine Karega, Mental Health Consultant

Wanjiru Ngunju, Public Health Consultant

Lucy Futaki, Mental Health Consultant

Key staff and stakeholders also reviewed and provided critical input, this includes:

1. Sankara Caroline Gitau- Executive Director

2. Angela Lagat- Advocacy , partnerships and branding manager

3. Diana Njuguna- Programs manager

4. Esther Ngunjiri- Hubs manager

A Note to You

This guide was developed as a tool to be used by adults who are in a position to talk to adolescent girls about mental health and wellness. We recognize that adolescence can be a confusing age with emotions worn on the sleeve, experimental behavior and physical changes. Yet it is an age of creativity, discovery and opportunity when it is accompanied by the right guidance.

Granted, it can be awkward to talk to adolescents about various topics. It is even harder as an adolescent to ask about these topics. This guide has selected topics that are key to the overall mental health of adolescent girls. While this is not exhaustive, we spoke to a few girls within this age bracket and from different backgrounds and the choice of these topics is drawn from their responses. This guide is also in response to some of the concerns brought by teachers who interact with adolescent girls daily who expressed a need for guidance on how to handle these key conversations.

How to use this guide

This guide is broken down into six chapters. Each chapter has activities that the facilitator can use to guide the discussion with the girls including instructions of how to lead the activities. The modules do not offer an end-all solution to the challenges adolescents face. The main goal is to open a gateway to a relationship between a growing young girl and a trusted adult.

Read it. There are brief notes at the beginning of each chapter explaining what will be discussed. The notes also point out some of the ways we as adults can perpetuate a culture that is more harmful than helpful to the development of a mentally healthy individual. We try to give some symptoms and behaviors that can be overtly observed in adolescents to indicate a problem.

Engage your audience. As you go through each chapter, there are prompts to Ask the girls what they think about the topic under discussion. This will allow you to conduct an interactive session that will be informative for both you and your audience.

Work in groups. We encourage working with groups of 8 to 10 girls if the opportunity allows. This will give you the opportunity to create a confidential setting where everyone can participate in the discussion. It is also possible to have a larger group discussing these topics and participating in the activities. If you have a larger group, divide them into smaller groups of at least 5 and have them contribute to the activity and present their ideas as a team.

Incorporate the Adolescent’s workbook. The Facilitator’s Guide is accompanied by the Adolescent’s Workbook that was created for use by adolescent girls. The workbook has similar topics and can be recommended to the girls to explore the topics discussed further.

Get a partner. A great way to work with groups is to get a co-facilitator. Having a partner allows you to track the responses from everyone in the group and to divide the work so that you are not exhausted after. Work as a team of 2 and agree on your roles beforehand.

Be prepared! Take time to go over the specific module you will be discussing before meeting with the girls. We recommend tackling one module at a given time. The session should ideally go on for an hour to an hour and a half. Any longer and you will lose your audience!

This workbook contains some activities within each module. The activities are geared to help you explore views, beliefs and ideas of the adolescents about the topic. There are specific instructions about special materials you will need for each activity.

Why mental health?

Adolescents who are aware of their well- being have a sense of identity, self-worth, sound family and peer relationships, the ability to be productive and to learn to tackle developmental challenges and use cultural resources to maximize growth.

The mental health of adolescent girls is affected by a variety of factors such as family relations, societal and cultural factors, peer relations and the self-directed expectations they put on themselves.

Who is an adolescent?

The WHO defines ‘Adolescents’ as individuals between the age group of 10-19 years old. At this age, there is rapid physical, cognitive and psychosocial growth. This affects how they think, feel, make decisions and interact with the world around them.

Who can use this guide?

This guide is meant for any adult that is interested in learning how to talk to adolescent girls about their wellness. Specifically, this guide can be used by:

Teachers engaging in life skills training with adolescent girls

Trainers in a workshop or mentorship session setting with girls

Parents who are keen on having conversations with their daughters about their mental health and wellbeing.

Glossary

Anxiety - An emotional state defined by persistent, excessive worries that don’t go away even in the absence of a stressor.

Depression - Is a serious medical illness that affects the way you think, act or feel.

Disorder- An illness that disrupts normal physical or mental actions.

Grief - Deep sadness caused by loss.

Loss - A state of deprivation of someone or something one had.

Peer - Someone who is the same age, has same values or same social status.

Self- esteem - A person's overall subjective sense of personal worth or value.

Stress - Emotional response typically caused by an external trigger.

Self-harm - Deliberate injury to one-self.

Suicide - Intentional act of ending your own life.

AIDS Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

CLA Canadian Lung Association

HIV Human Immunodeficiency Virus

WHO World Health Organisation Abbreviations

TALKING ABOUT SELF IDENTITY AND DISCOVERY

“Without the possibility of being bad at something, you will never be extraordinary." Pushing yourself to that limit "allows you to embrace vulnerability and surprise yourself… It doesn't ever get comfortable. But it does get familiar.”

~Lupita Nyong'o

To help adolescents identify social and cultural factors that help shape

To equip adolescents with skills to help them improve their self-esteem.

Study the entire session and ensure that you are prepared and comfortable with the content and activities.

Review the questions and activities for this module and take note of the expected responses from the participants.

Prepare materials (flipcharts, pens, activity handouts) before the

This session should take approximately 1hour and 30minutes. Ensure that you will have enough time without distractions.

Have the girls arrange their chairs in a circle so that you can see everyone and they can all see you.

This session can be facilitated by two facilitators who can help each other out. Decide your roles beforehand.

Flipchart or whiteboard/ blackboard

Marker pens and smaller colored pens

Plain A4 papers or printouts of the Stardust Identity Chart

Notes

If you recall anything about being an adolescent it must be the chaos, confusion and sensitivity that came with this age. You might have experienced the struggle to become the you that you are now. You might also have experienced the pressure of parental expectations, peers and self-imposed pressure to become the best version of yourself.

Adolescents today are no different. Their journey to forming an identity is underway. This journey is shaped by family, cultural and societal expectations, experiences with school and the media, and friends. Young people also take active steps to make choices that shape their identity.

Adolescent identity is developed in part based on relationships and feedback received from others. As they keep growing and their brains continue to develop, their adolescent identity is also likely to change (https://parentandteen.com/developing-adolescent-identity/).

While they may not experience all of the following, here are some ways adolescents may be changing; Desire to identify themselves in multiple ways outside of their role in the family

Increase awareness of themselves as part of a peer group (for some, navigating where they fit into the social landscape may take time and involve multiple changes)

Develop flexibility in how they present themselves in different situations

Ask the girls what are some of the changes they have noticed about themselves. Does how they present themselves in different situations differ?

Supporting the navigation process

As they become older, some values and principles that match them become more concrete. During the exploration process, they may wear different hats to test them out.

As they explore, they may find something new and exciting. If they share something that you have already given deep consideration, remember that it is still new to them and they may be looking for a sounding board rather than expert answers.

Remember, that how teens see themselves is also shaped by how others see them. They may also be influenced by how the media portrays people their age. Exposure to various opportunities and experiences determines the ‘possible selves’ they can be.

Ask the girls if they ever compare themselves to other adolescents from other countries.

Are there any similarities? Are there any differences?

What defines identity?

Ask the girls what they think an identity is? Is their identity permanent or does it change?

Identity encompasses the values people hold. It is made up of multiple roles- such as a girl, sister, Kenyan citizen- and each holds meaning and expectations that are internalized into one’s identity. Our identity can be made up of 3 components. For adolescents, defining these concepts is a journey that can be confusing and scary but with a little help, it can be a fun and empowering process.

The ideal self- This is the person you want to be

Self-image- How you see yourself, including your physical characteristics, personality traits and your role in society.

Self-esteem- This is how much you like, accept or value yourself. This can be impacted by things like how others see you, how you compare yourself to others and your role in society (Argyle M. Social encounters: Contributions to social interaction. 1st ed. Routledge; 2008).

Personal Identities and Social Identities

Personal identity is how you see yourself as ‘different’ from those around you. This includes your education, interests, personality traits and the roles you hold in society. Social identities are the identities that you share with similar group members. These include categories such as gender identity, sexual orientation, religion and even race. Sharing these similarities gives you a feeling of ‘belongingness’ and ‘community’. However, it can also create a possibility of feeling isolated or stigmatized when you belong to a certain group.

Ask the girls if how they present themselves in different situations differ? Do they feel inauthentic when moving through different situations?

Clarify that as they become older, some values and principles that match them become more concrete. During the exploration process, they may wear different hats to test them out. As they explore, they may find something new and exciting.

A major task of self-development during adolescence is the differentiation of multiple selves as a function of social context. So a girl may find herself cheerful and excited with friends but irritable and snappy when with their parents. As they mature cognitively, a sense of stability is achieved in their identity.

Culture and Identity Formation

Remember, that how adolescents see themselves is also shaped by how others see them. For example, if parents see their children as worthless, they will continue to define themselves as worthless. People who perceive themselves as likeable may remember more positive than negative statements.

Johari Window - A great exercise to improve self awareness as part of a community is to find out how people see you. The Johari Window is a simple and useful tool for illustrating and improving self-awareness. The Johari Window's four regions, (areas, quadrants, or perspectives) are as follows, showing the quadrant numbers and commonly used names:

Johari Window Four Regions

What is known by the person about him/herself and is also known by othersopen area, open self, free area, free self, or 'the arena' What is unknown by the person about him/herself but which others knowblind area, blind self, or 'blindspot'

What the person knows about him/ herself that others do not know - hidden area (façade), hidden self, avoided area, avoided self or 'facade' What is unknown by the person about him/herself and is also unknown by others - unknown area or unknown self

Hand out blank pieces of paper to the girls. Instruct them to draw the four windows as shown above. Instruct the girls to fill in the quadrants one by one. For the Blind Self, allow them to ask a friend or classmate. The Unknown Self quadrant will be left blank as it is room for discovery and future growth. Have the girls lay out their Johari windows and ask a few to mention some things they have learnt about themselves that they did not know.

‘The views of society can be discouraging to girls for example when people see a girl playing football with boys they say she is going to be soiled soon’

High school student, 2021

‘In my area when the pandemic started the community formed a program to talk to girls and encourage them to make better choices in life’

High school student, 2021

The society we live in can offer few opportunities to girls about what they can do and who they can be. But that does not mean we cannot start creating these spaces.

Supporting the navigation process

There are three goals required for the task of identity formation.

1. Discovering and developing potential

Personal potentials refer to those things that a person can do better than other things. Help the adolescents to pinpoint activities that they are motivated to do. The development of these skills requires time, effort and willingness to tolerate obstacles met along the way.

2. Choosing your purpose in life

Choosing what one wants to accomplish in life is necessary for success. Remind the girls that in order to achieve success they should have objectives that are compatible with their talents and skills. Choosing a purpose that is inauthentic to our identity usually leads to frustration and failure.

3. Recognise that identity is never final

By being flexible and giving themselves the opportunity to fail and learn new things, adolescents will find more happiness and less anxiety about life. Remind them that trying to impress other people by acting out of character causes self-doubt, self-consciousness and negative thoughts.

Activity

The Stardust Identity Chart is a graphic tool that can help adolescents to consider the many things that shape their identities. The image below offers a guide of what it should look like. You can use some of the self- reflection questions as prompts to help the girls fill the arrows on the stardust chart. With a little more confidence, you can ask some of your own questions.

NOTE- The Student’s Workbook has a few reflection questions to help the girls explore their identity further. You can refer to some of these during the Stardust Identity Chart activity.

After everyone is done with the activity, have the girls lay out their identity charts in front of them.

Ask them what labels they have put on the arrows facing inwards. What words or phrases do they use to describe themselves?

What labels are on the arrows facing outwards? How do they think other people describe themselves?

Are there similarities with other members in the group?

Does anything standout? (Does someone have a label that is not shared with other group members?)

Self-awareness reflection questions

The following questions can be used to guide the girls in creating the labels on the Stardust Identity Chart activity.

1.Describe yourself in three words

2.What does your ideal ‘you’ look like?

3.What kind of dreams and goals do you have?

4.Has your personality changed since childhood?

5.What qualities do you most admire in yourself?

6.What is your biggest weakness?

7.What is your biggest strength?

8.What are the roles that define a girl’s identity in our society?

Stardust Identity Chart

Directions: Write your name (or the name of a person or character) in the circle.

At the ends of the arrows pointing outward, write words or phrases that describe what you consider to be key aspects of your identity.

At the ends of the arrows pointing inward, write labels others might use to describe you. Add more arrows as needed.

You may hand out blank pieces of paper or foolscaps with multiple-colored pens that the participants can use to create different labels. You may participate in this activity to show the girls what makes up part of your own identity.

British

catholic

sister

Daughter

Halfghanian

Likes marvel films

TALKING ABOUT SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS

“Peer pressure is not always negative. Sometimes, it inculcates new hobbies, habits, attitudes, health conscience or a strong urge to succeed amongst people and where this happens, it is positive.”

~Adeyemi Raphael Oluwamayowa

Objectives:

To identify signs of positive and negative peer influence in adolescents

To identify adolescents at risk of negative peer influence

To apply strategies to help adolescents cope with negative peer influence

Advance preparation:

Study the entire session and ensure that you are prepared and comfortable with the content and activities.

Review the questions and activities for this module and take note of the expected responses from the participants.

Prepare materials (flipcharts, pens, activity handouts) before the session

This session should take approximately 1hour and 30minutes. Ensure that you will have enough time without distractions

Have the girls arrange their chairs in a circle so that you can see everyone and they can all see you.

This session can be facilitated by two facilitators who can help each other out. Decide your roles beforehand.

Materials required

Flipchart or whiteboard/blackboard

Plain A4 papers for each participant to write on 3 different coloured marker pens

Pens

Peer Pressure Role-Playing handouts

Peer pressure role play scenarios.

Notes

Peers play a big role in the social and emotional development of adolescents. It is natural, healthy and important for adolescents to have and rely on peers as they grow and mature. Research findings from the Parent Further publication on peer pressure showed that only 10% of the respondents said they have never been influenced by peer pressure.

While the majority of peers can negatively impact an adolescent, they can be supportive and positive. Positive peer influence includes helping each other develop new skills, or stimulate interest in extracurricular activities, books, or music. Negative peer influence can include use of alcohol and drugs, sharing of inappropriate online materials, encouraging each other to steal, cheat in examinations, skip classes or become involved in other risky behaviors.

Some studies have been conducted to show the impact of negative peer pressure are;

According to The Canadian Lung Association (CLA), 70% of teens who smoked did so because their friends smoked.

According to The Body 23 % of females feel pressure from their friends to have sex.

According to the Foundation of a drug free world, 55% of teens tried drugs for the first time because their peers pressured them.

Ask the girls if peer pressure is common in their friend groups.

Can they differentiate between negative and positive peer pressure? Do they ever pressure their friends to engage in activities with them?

Signs that an adolescent is undergoing peer pressure

Ask the girls the following questions and indicate their responses on the flipchart or board.

Are there signs that a friend you know is undergoing peer pressure? How have they changed?

You will notice some changes in an adolescent who is undergoing pressure. The following are signs that you should watch out for in adolescents;

Antisocial behavior

Hostility towards others

Use of alcohol or drugs

Reduced school performance

Over-eating or decreased appetite

Reluctance to go to school or study

Mood swings, tearful or feelings of hopelessness

Lack of sleep, oversleeping or waking up earlier than usual

Sudden changes in behavior, mostly for no obvious reason

Verbal statements about wanting to give up, or life not being worth living

Withdrawal from activities that the adolescent girl used to like and engage in

Adolescents at risk of negative peer pressure

Some adolescents are more at risk of negative peer pressure. They include adolescents;

Who have few friends

Who have poor self-esteem

Who have special needs

What you can do to help adolescents overcome peer pressure?

Ask the girls some of the things they do to overcome peer pressure.

Do they always succeed?

Are there adults that talk to them about peer pressure and how to overcome it?

Create an environment that fosters open and honest communication: Let the adolescents know they can come to you if they are feeling pressured to do things that do not sit right with them.

Nurture adolescents’ abilities and self-esteem: Adolescents with positive self-concept, confidence and self-worth will avert negative influences from peers.

Encourage diverse relationships: Teachers should encourage adolescents from different backgrounds to engage and form relationships.

Equip adolescents with the skills necessary to resist negative influence: Equip adolescents with the ability to analyse a situation while looking at the pros and cons of making a decision around the need to fit in

Teaching the adolescents exit strategies or ways to say ‘no’ to negative influences. Present adolescents with case scenarios and work with them on strategies to resist negative peer influence. You can include role plays for effect.

Sources of help for teachers

To improve your interaction with adolescents and guiding them through their friendships, you can access courses from the following websites:

Counselling skills certificate course (Beginner to Advanced). https://www.udemy.com

Existential well-being counselling: A person-centered experiential approach.

https://www.edx.org/course/existential-well-being-counseling-a-pers on-centere

Peer Pressure Role-Playing

Objectives:

The adolescent girl will:

Evaluate the effects of positive and negative peer influence

Share real-life experiences of peer pressure

Materials

Peer Pressure Role-Playing handout for each adolescent girl

Pen or pencil for each adolescent girl

Instructions

Offer the adolescent girl a copy of the peer pressure role play hand out.

Give the adolescent girl ample time (45 minutes) to go through the handout.

Instruct the adolescent girl to fill in the questions that follow in each case scenario.

Afterward, discuss some realistic examples of good and bad peer pressure with the group of adolescent girls and how they can be equally powerful.

Peer Pressure Role-Playing Instructions:

Read each scene and answer the questions below each one.

Ashley: Look at her. She’s such a loser

Kimberly: Who?

Ashley: That new student. What’s she even wearing anyway? That skirt is so last century.

Kimberly: She’s OK. She’s just quiet.

Ashley: She’s OK? Did you see her in the debate club? She's the reason why we lost today. I was talking with the girls and we think we’re going to have to teach her a lesson.

Kimberly: What kind of lesson?

Ashley: You know. Just scare her a little on the way home today. You in?

Kimberly: I don’t know. I think we should just leave her alone.

Ashley: You are such a coward. Are you worried about getting in trouble?

Kimberly: It’s not that. It’s just that ...

Ashley: Just that what? You’d rather hang out with that loser than us? Fine. I’ll find someone else to go to the party with me this weekend.

Kimberly: That’s not what I said, OK?

Ashley: Wow, Kimberly. You used to be so cool. Now you’re like my little sister or something. Are you with us today or not?

Fill the spaces after each question

1.Who’s doing the pressuring?

2.What kind of words is she using to do it?

3.What effect might those words have?

4.Is influence being used in a positive or negative way?

Maria: I wish you would try out for the school cookout competition with me.

Zainab: But I can’t cook well. I like knitting.

Maria: Who says you can’t do both? Besides, I’ve heard you cook delicious meals at home.

Zainab: Me? No, I don’t.

Maria: Yes, you do. You have great talent. You just try to hide it.

Zainab: Well, it’s embarrassing to cook in front of all the students, parents and teachers.

Maria: I have heard you made great pilau at your sister’s wedding. I also heard that there were 200 guests.

Zainab: I don’t know. It is just scary to cook in front of hundreds of people.

Maria: Well, it can’t hurt to try, can it? Plus, Wema and Grace are joining the cookout. It would be so cool for all four of us to do it together.

Zainab: What if I get scared and fail the team?

Maria: I’m pretty sure you won’t fail us. But if you do, we shall buy ice cream to make you feel better. Look, just think about it, OK? And stop worrying too much. It’ll be fun!

Fill the spaces after each question

1.Who’s doing the pressuring?

2.What kind of words is she using to do it?

3.What effect might those words have?

4.Is influence being used in a positive or negative way?

TALKING ABOUT SEXUAL HEALTH AND POWER

“We should tell them the truth in a way that is adapted to their age….understanding sexuality is not just technical knowledge about where babies come from…..it is about how your kids feel about themselves, the world around them and their personal boundaries.”

~Maria Travkova

Objectives

To equip adolescents with knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that will empower them to realize their health, well-being and dignity

To help them develop respectful social and sexual relationships

To consider how their choices affect their own well-being and that of others

Advance preparation

Study the entire session and ensure that you are prepared and comfortable with the content and activities.

Review the questions and activities for this module and take note of the expected responses from the participants.

Prepare materials (flipcharts, pens, activity handouts) before the session

This session should take approximately 1hour and 30minutes. Ensure that you will have enough time without distractions

Have the girls arrange their chairs in a circle so that you can see everyone and they can all see you.

This session can be facilitated by two facilitators who can help each other out. Decide your roles beforehand.

Materials needed

Flipchart or whiteboard/ blackboard

Marker pens and smaller colored pens

Blank pieces of paper for the Myth vs Facts Game

Activity

Saying ‘NO’ to sex assertively

Myths vs Facts Game- Use this activity to debunk some beliefs adolescents have about periods and sex.

The period of adolescence is marked by great physical, emotional and behavioral changes. These changes are often accompanied by intense feelings and reactions from adolescents that makes it uncomfortable to have conversations about certain topics with them. Our cultural background and practices also have an impact on how we handle conversations surrounding sex and sexual health with adolescents. As it relates to girls, talking about sexual health has always been done in secrecy and an air of shame has been created around these topics. This has resulted in women being overlooked socially and economically; girls’ education taking a lesser place in society and more saddening; a half of the world’s population living in shame.

Ask the girls:

On a scale of 1-10 how comfortable do you feel discussing periods and sexual health issues?

Who do you discuss such issues with?

Indicate their responses on a flipchart or blackboard and explore their responses by asking them to explain further what they mean.

Young people have a right to the information and services they need to make healthy decisions about their lives. Providing young people with accurate reproductive health information promotes sexual health and wellbeing. This includes supporting healthy, responsible and positive life experiences, as well as preventing disease and unintended pregnancy. We spoke to a few adolescent girls about their concerns and knowledge on sexual health and engaging in sexual activity.

I sometimes don't ask my parents questions (about periods and sex) because they'll be left with fear about what I want to know and what I am doing.

High school student, 2021

Parents don't really participate in talking about sex and related topics but expect you to know this information.

High school student, 2021

We want to know more about sex because there is also a lot of information coming up that is confusing to us.

High school student,2021

The bloody issue!

Menstruation is a natural part of a healthy girl’s life. Most girls get their first period when they are around 12. But some start as early as 10 years old while others get it later at 15 years old. The menstrual cycle is roughly 28 days long, but it can be shorter or longer. While a person’s menstrual cycles may be consistent – even predictable – they can also change or vary, particularly in the first few years after menarche (the first period).

Access to hygienic and affordable management systems during menstruation is a matter of human dignity. However, girls and women face issues such as menstrual-related teasing, exclusion, period shaming and period poverty.

Period shaming - Can come from being teased/picked on for being on your period.

Can also come from being denied to use the toilet during class time. Adolescents may be too embarrassed to explain why they need to be excused or why it might to be an emergency.

Exclusion - Myths and misconceptions about periods has reduced in women being excluded from various roles and settings.

Period poverty - the struggle many women and girls face while trying to afford menstrual products.

Ask the girls if they have experienced period shaming or teasing. Who instigated the teasing?

What do they use to control blood flow when they are on their periods? Are they ever concerned about their ability to afford these products?

Girls’ menstruation marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. This transition in our society has also been tied to their ‘readiness’ to participate in marriage and sexual activity. There are also many myths related to this period in a girl’s development.

NOTE: The Student’s Workbook highlights some of the myths from various communities. Discuss these with the girls and find out about some of the myths they might have heard.

Talking about uncomfortable topics

It is not easy but it is possible! Young people will often giggle with embarrassment or excitement when you talk about sex or reproduction. Here are a few tips to help you tackle difficult conversations:

1.Be clear on your values (and biases)

How do you feel about the issues you are about to discuss? We all have different values that impact our view on this and many topics.

2.Plan ahead!

Decide what you want to talk about beforehand and do your research. Adolescents are getting information from the internet and social media platforms such as TikTok, Instagram and YouTube; use this as an information source as well.

3.You don’t know everything (you don’t have to)

You may not have an answer for all the questions you receive. Be honest about it. You can turn it into a conversation or a project in which you engage the adolescents in seeking information. You could also offer to go find more information and bring the answer in a later session

4.Do not dismiss or look down on what the adolescents know

Appreciate that they have been exposed to a variety of information and experiences. try to make them feel that their experiences are of value and importance.

5.Set your own limits

Your audience may be excited to have a conversation that they may not typically have freely with an adult. It is important to be as open and as honest as you can. However, explain if you feel uncomfortable answering a particular question. Historically, talking about sexual and reproductive health of women was done in hushed tones and in secrecy, creating a sense of shame and inferiority. But being a girl and a woman is nothing to be ashamed of. Good communication on periods and sexual health require:

Setting the scene

1.Set up

An environment that encourages adolescents to ask questions and discuss their concerns. Ensure that you are in a place that can protect their privacy and prevent other people from eavesdropping . Sit in a circle on the same level with your audience.

2.Remain calm, they’ll open up…

Exercise patience and understanding of the difficulty adolescents have in talking about periods and sex. Use a little humor to break the ice and, if appropriate, share some of your own experiences.

3.Show respect

Respect their feelings, opinions and decisions. You may not agree with them, but demonstrating respect opens them up to listening to a different point of view.

4.Weigh the pros and cons

Have discussions that analyze the advantages and disadvantages of different options.

5.Make it applicable

Discuss how adolescents can make informed decisions and ways to put them into action.

Sex and sexuality

Contrary to the belief that teaching adolescents about sex will only make them more eager to engage in sexual activity; research has shown that adolescents who engage in conversations about sex and sexual health with a trusted adult delay sexual engagement and are better equipped to protect themselves in sexual activities.

Ask the girls what the difference is between sex and sexuality

Sex - Whether a person is male or female and is determined by their sexual organs and how people express their gender.

Sexuality - This is how people experience and express themselves sexually. It is about your sexual feelings, thoughts, attractions and behaviours towards other people.

Ask the girls what makes up their sexuality

Expect some of these answers

Body image: How we look and feel about ourselves, and how we appear to others. Gender roles: The way we express being male or female. The expectations people have for us based on our sex.

Relationships: The ways we interact with others and express our feelings for them. Intimacy: Close sharing of thoughts or feelings in a relationship, may or may not involve physical closeness.

Love: Feelings of affection and how we express those feelings for others.

Sexual arousal: The different things that excite us sexually.

Social roles: How we contribute to and fit into society.

Genitals: The parts of our bodies that define our sex. They are part of reproduction and sexual pleasure.

Healthy vs Unhealthy Sexuality

Sexual behaviors can be both healthy and unhealthy. Sexual behavior is not just penile-vaginal penetration. Sexual behaviors also include expressions of ‘outercourse’. Some outercourse examples include kissing, massage, masturbating, using sex toys on each other, dry humping (grinding), and talking about your fantasies.

It is important for adolescents to be able to identify the difference before making the choice to engage in sexual behavior.

Healthy sexuality can be thought of as:

Having appreciation for one's own body,

Seeking out knowledge regarding reproduction, understanding that human development includes sexual development (i.e., reproduction, genital sexual experiences),

Interacting with both genders respectfully and appropriately, Understanding and respecting sexual orientation, Appropriately expressing love and intimacy, Developing and maintaining meaningful relationships while avoiding exploitative or manipulative ones.

Having the ability to enjoy and control sexual and reproductive behavior without feelings of guilt, fear, or shame

Ask the girls what risky/ unhealthy sexual behavior includes. What are the consequences of engaging in unhealthy sexual behaviors?

Unhealthy sexual behaviors include:

Starting sex at a young age

Unprotected sex

Sex with multiple patners

Having sex with a high-risk partner (partner who has multiple other sex partners)

Exchanging explicit pictures and images online

Engaging in commercial sex work

Risky sexual behavior can lead to:

Unintended pregnancies

Abortion

Contraction of Sexually Transmitted Infections

Higher risk of HIV/AIDS

Making Decisions

Emphasize to the girls that deciding to have sex is a big decision that only they can make. However, they can always talk to a trusted adult such as a parent or teacher before making this big decision. Remind the girls that some may have already had sex and are having some regrets and feelings of anxiety about it. It is still important to talk to a trusted adult about these feelings. It may be a little awkward and embarrassing but it is nothing to feel ashamed about.

The activity below can help girls think about situations that pressure them to have sex and how they can delay sex until they are ready to make this decision.

Activity 1: Saying ‘no’ to sex assertively

1. Tell the group to imagine they have decided they want to say ‘no’ to sex. Tell them to think of some places and situations where they might be in danger of having sex.

2. Divide the group into pairs. Give each pair two of the situations to role-play. Start with the first situation. One person should try to persuade the other one to have sex, using any ways they wish. The person who wants to say ‘no’ should use strong ways to keep to his or her decision.

3. The pairs now change over and role-play the second situation, with the characters reversed. This allows them both to practice being strong in saying no.

4. Bring everyone together and watch some of the role-plays, choosing different situations. For example, people of different ages; the pair love each other; they have just met; money is offered.

5. Ask: —What helped you to keep to your decision about delaying sex? —Which arguments were difficult to resist? —Which were the best ways to resist them?

6. Ask what people have learned from the activity and summarize.

For this game give the girls 3 blank pieces of paper. Have them write on one FACT; on another MYTH; and on the last one I DON’T KNOW.

On a flipchart or blackboard draw 3 columns indicating FACT, MYTH and I DON’T KNOW.

Read out the statements and instruct the girls to raise a card if they think the statement is a FACT or MYTH or if they DO NOT KNOW.

Write the number of responses each statement gets on the flip chart or blackboard indicating how many people thought the statement was a FACT, MYTH or they DO NOT KNOW

When done, go over the statements with the girls and correct them. Ask a few of them why they gave the responses they did. This is a great opportunity to explore what they have learnt from society and other friends.

Myth vs Fact game

1.Generally, girls begin puberty before boys FACT- Most girls do begin puberty about one or two years earlier than boys do

2.All girls should begin periods at the same age MYTH- Every girl’s body develops differently. Most girls get their first period when they are around 12. But some start as early as 10 years old while others get it later at 15 years old which is okay.

3.If a girl misses her period, she is definitely pregnant MYTH- When girls first start menstruating, they often have irregular periods and may even skip a month or two at times. However, if a young girl has had sexual intercourse, missing a period can be a sign of pregnancy.

4.Getting your period means you are ready to start having sex and ready for marriage.

MYTH- Girls get their periods as part of physical growth and development. This does not mean they are mentally and emotionally ready to have sex or to be married.

6.Girls on their period can exercise and participate in active sports

FACT- Having your period does not limit your ability to continue your typical everyday life. Women everyday go to work, participate in sports and enjoy their lives while on their periods.

7.Boys need sex more than girls do.

MYTH- Neither boys nor girls need to have sex to be healthy. It’s normal and healthy for boys and girls to have sexual feelings, however it’s important for everyone to think seriously about what they want to do and not do when it comes to acting on those feelings. Sexual intercourse at an early age often leads to confusion, guilt, regret, and sometimes even unplanned pregnancy and STIs, including HIV. For these reasons, it’s best to wait until you’re older to start having sexual intercourse

Resources to guide you further

Tuko Pamoja; A guide for talking with young people about their reproductive health https://path.azureedge.net/media/documents/CP_kenya_pht_manual. pdf

TALKING ABOUT ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION

“Rejection triggers my anxiety and depression. Once I learn how to choose myself and be completely validated by that choice, I’ll put the trigger in my hands and not in the hands of others.”

~Lizzo

Objectives

By the end of this chapter, the learner should be able to:

Understand the difference between stress, anxiety and depression and how they correlate.

Identify signs and symptoms related to anxiety and depression. Identify healthy coping skills to deal with anxiety and depression

Advance preparation

Study the entire session and ensure that you are prepared and comfortable with the content and activities.

Review the questions and activities for this module and take note of the expected responses from the participants. Prepare materials (flipcharts, pens, activity handouts) before the session

This session should take approximately 1hour and 30minutes. Ensure that you will have enough time without distractions

Have the girls arrange their chairs in a circle so that you can see everyone and they can all see you.

This session can be facilitated by two facilitators who can help each other out. Decide your roles beforehand.

Flipchart or whiteboard/ blackboard

Marker pens and smaller colored pens

Materials needed Activity

Reflection questions

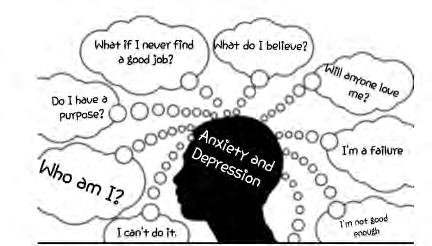

Ask questions from the image below and have the girls have a thought process and give their responses. No right or wrong answer.

Notes

Ask the girls:

How would you describe stress and anxiety? Is there a difference between the two?

What are some of the reasons that cause you stress and anxiety?

Using the questions above, have a discussion with the girls on what they know about the topic.

Stress is an emotional response typically caused by an external trigger. The trigger can be short-term, such as an assignment deadline or a fight with a loved one; or long-term, such as being unable to go to school, discrimination, or chronic illness.

Anxiety on the other hand, is an emotional state defined by persistent, excessive worries that don’t go away even in the absence of a stressor. It's the fear of what is going to happen. It becomes a problem when it’s out of proportion to the situation, and interferes with a person’s ability to undertake daily tasks. An overly anxious adolescent might withdraw from activities because of fear, and might not be able to recover unless given reassurance. Adolescents mostly get anxiety when they go through body changes, social acceptance or when they have conflicts of their independence. They may appear extremely shy and refuse to engage in new experiences and in an attempt to deny their worries, they may engage in risky behaviors such as experimenting with drugs. Adolescents who are abled differently may have worries about being judged because of their appearance, not being able to make friends or even missing out on school activities.

An adolescent who has been anxious since childhood may have a lifestyle built around her anxieties: the activities and environments she chooses and those she rules out, the friends she is comfortable with, the expectations and limitations she has trained her family, friends, and teachers to accept. That’s why it’s more challenging to treat anxiety the longer a child has lived with it, and developed unhealthy coping mechanisms to manage it.

Ask the girls what are some of the situations that make them get anxious. Ask the girls what are some of the signs they have noted with themselves or their peers to show anxiety.

Some common anxiety disorders in adolescence are:

1. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), which is an excessive worry of everyday life events. Adolescence may worry about their performance in school, relationships with friends or their family situation. Some symptoms of GAD are:

Being irritable,

Difficulty concentrating

Feeling restless.

Lack of sleep

Muscle tension

2. Separation anxiety is an excessive worry about being away from their loved one. It can be triggered by events that lead to separation from a loved one. Genetics may also play a role in developing the disorder.

Some signs to show an adolescent is going through SAD are:

Having a persistent fear when they are away from home

When they are constantly worrying about losing a parent or a loved one

Do not want to be left home alone

When they have repeated nightmares about separation

3. Social phobia is a persistent fear of being around people. Adolescents may show social phobia if they have excessive worry before attending a social event or when preparing for a class presentation.

"You can get nervous and be like, 'oh my god, someone's not going to like me, I'm going to say something that's wrong, I'm going to do something that's wrong, I'm afraid someone's going to look at me funny or they don't think my life is cool," Lana said. "Then I realized it's just, it's anxiety and I think it's something we all go through."

Lana Condor

It’s normal for adolescents to have mixed emotions. Their sad feelings can last several days. Typically, when someone is sad, they can pinpoint a specific reason for their feelings. However, depression can sometimes appear out of nowhere and it may be hard for someone to identify why they feel the way they do. In other cases, even when the cause of depression is known, the reaction to that event can seem exaggerated in proportion to that experience.

Issues such as peer pressure, academic expectations and changing bodies can bring a lot of ups and downs for adolescents. It’s normal for adolescents to have mixed emotions. Their sad feelings can last several days. However, a prolonged feeling of sadness can show signs of depression.

Ask the girls what are some of the reasons that make them extremely sad and behavioral changes they have noted when they are unhappy.

Depression, however, is a persistent and prolonged feeling of sadness. For an adolescent with depression the symptoms recognizable are:

Feeling deep sadness or hopelessness.

Loss of pleasure or interest in activities that once excited them.

Worry, and irritability.

Difficulty in concentrating

Feeling worthless and guilty

Drastic changes in appetite or weight.

Difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep or sleeping too much.

Withdrawing from friends and family.

Restlessness

Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide.

Ask the girls how they cope with anxiety and depression. Some answers will include:

Engaging in physical Activity

Listening to Music

Talking to someone about their experiences

Creating art through drawing, dance or poetry

Journaling

Reading books

How to communicate with an adolescent going through depression

Resist any urge to criticize or pass judgment. The important thing is communication. You’ll do the most good by simply letting the adolescent know that you’re there for them, fully and unconditionally. Don’t give up even if they shut you out at first. Talking about what they are going through can be tough on them and they may have a hard time expressing what they’re feeling. Be respectful of the adolescent’s comfort level while still emphasizing your concern and willingness to listen.

Acknowledge their feelings even if their feelings or concerns appear irrational to you. Well-meaning attempts to explain other types of situations will just come across to them as if you don’t take their emotions seriously. Simply acknowledging the pain and sadness they are experiencing can go a long way in building a safe space for communication.

If the adolescent claims nothing is wrong but has no explanation for what is causing the depressed behavior, you should trust your instincts, especially If they won’t open up to you. Follow up on having a conversation with them. Get them involved by suggesting activities they might be interested in such as sports, clubs, and dance or music classes?

Encourage them to live a healthy lifestyle by exercising, participating in engaging activities, eating healthy and maintaining a good sleep schedule. Refer them to a professional to seek medical assistance such as a school counsellor or an external therapist.

It is important to remove the stigma associated with anxiety and depression. Adolescents who have been experiencing anxious behaviors should be able to seek help and be advised on the suitable ways of treatment.

Sometimes as adults, it’s possible to ignore the fact that depression actually occurs in adolescents. For instance, I had an encounter with an adolescent girl going through depression and none of the teachers took that seriously and instead of finding ways to deal with the situation, they ended up creating a stigma even among the rest of the students which made it unbearable for the girl to continue studying in the school. It is therefore important to look out for symptoms and follow up on their recovery journey.

You don't feel like you're hurting yourself when you're cutting. You feel like this is the only way to take care of yourself

Marilee Strong

TALKING ABOUT LOSS AND GRIEF

“Grieving

doesn't make you imperfect. It makes you human.”

~Sarah Dessen

Objectives

To identify loss for adolescents

To identify the process of grief in adolescents

To observe for signs of grief in adolescents

To apply strategies to help adolescents cope with grief

Advance preparation

Study the entire session and ensure that you are prepared and comfortable with the content and activities. Review the questions and activities for this module and take note of the expected responses from the participants. Prepare materials (flipcharts, pens, activity handouts) before the session

This session should take approximately 1hour and 30minutes. Ensure that you will have enough time without distractions

Have the girls arrange their chairs in a circle so that you can see everyone and they can all see you.

This session can be facilitated by two facilitators who can help each other out. Decide your roles beforehand.

Materials needed

Flipchart or whiteboard/ blackboard

Marker pens and smaller colored pens

Plain A4 papers for each participant to write on 3 different colored markers

Pens

Grief Self-Exploration House Activity handouts

Activity

Group Activity

Individual Activity; Grief Self- Exploration House

Notes

Adolescents like adults’ experience grief after loss. Grief is a normal reaction to loss. Your support to adolescents during grief is important. Adolescent girls experience loss through the following experiences;

Loss of childhood as they journey to adulthood

Loss through death of a parent (s), sibling, relative, friend

Loss of a parent through separation or divorce

Loss of sense of innocence after the first sexual experience

Loss of friendship

Loss of confidence

Loss of a body part following treatment/ surgery or accidents

Ask the girls what kinds of losses they have experienced. What kind of emotions did they have about the loss?

Adolescent girls may experience different types of losses that include:

Loss of childhood as they journey to adulthood, or by being caregivers at a young age, or through child abuse

Loss through death of a parent(s), sibling, relative, friend

Loss of a parent through separation or divorce

Loss of sense of innocence after the first sexual experience

Loss of friendship/ loss of interpersonal relationships among others i.e. fellow students

Loss of confidence

Loss of a body part following treatment/ surgery or accidents

Loss of health due to chronic illnesses e.g. chronic kidney disease

Loss of family bond

Loss of finances dues to loss of parents’ income or misuse of family resources by parents

Loss of self-image e.g. one can be anorexic or obese

Loss of trust and parental rejection

These losses can lead to grief if;

An adolescent girl is ignored consistently as she is growing up

She has grown in fear of her parents or guardian’s strict restrictions

She has suppressed feelings of heartache that are ignored.

Her culture suppresses girls and women

She experiences demeaning, intimidating words, loud demeaning, abrasive and hostile voice which is insensitive to her needs, feelings and rights

She is constantly threatened

She is body shamed for being thin or obese

She is a teen mother

She has undergone childhood negligence

The process of grief

After loss, an adolescent girl will undergo overwhelming pain. The process of grief has been described by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross an Swiss American Psychiatrist, who created the Kübler-Ross model. This model consists of five stages of grief and loss. It will be good to note that not every adolescent will undergo all the stages. Others will not go through the exact sequence of grief, as shown below. Every adolescent girl will undergo grief differently.

How will you know that an adolescent girl is undergoing grief?

The signs of grief are hard to miss. Keep a keen eye on the adolescent girls that you are in constant contact with.

Watch out for the following signs of grief in some adolescent girls:

Being moody

Having negative feelings

Becoming a loner and talking less

Using drugs or alcohol to numb the pain

Watching sad movies or reading sad books

Losing passion for activities they liked before

Covering fears with rebellion and being argumentative

Blaming anyone they feel might be responsible for the loss

Exaggerating their maturity in order to mask an inability to cope

Feeling powerless over their loss and trying to find some meaning from it

Struggling to prepare for what now feels like an uncertain future

Ask the girls:

What are the changes in behavior that you might notice in people who have experienced a loss?

Have you ever had to support a friend who experienced loss? How did you help them?

An adolescent spends more time in school than they do at home. You have an opportunity to help an adolescent cope with grief. You can apply the following strategies;

Create dialogue with an adolescent girl who is undergoing grief: Create time to talk to the adolescent in an open and nonjudgmental environment.

Listen to her and look out for non-verbal cues such as hesitating while expressing herself. Give the adolescent time to express herself. Giving the adolescent time alone: to reflect about themselves and how the loss has affected them and how she is coping with grief. Refer the girls to credible guidance and counseling professionals, psychiatrists, psychologists or religious leaders.

Help the girls to avoid rash or irrational decisions that may be as a result of grief. Guiding the adolescent through activities that can facilitate healing: activities that can help ease the pain of loss include; journaling, encouraging the adolescent to be engaged in sports and other extracurricular activities.

Use inclusive phrases such as;

During grief friendships change; some deepen while others are lost, this is normal.

Loss is hard on you and those around you.

You have lost your innocence through pain, you are different and that's okay. Don't look for love in the wrong places, it will hurt you more.

Extend grace to yourself, some days will be harder than others . Talk about what you are feeling during grief. Some days talking is therapeutic and others draining.

Grief can affect daily routine activities. It may cause panic and tears. What support have you been offering adolescent girls undergoing loss and grief?

Further support of an adolescent

If you notice any of the following signs, you will need to refer the adolescent to a grief counsellor or psychologist for further management:

Denial of the death of a loved one

Exhibits signs of chronic depression

Chronically angry or hostile

Suffers anxiety, panic or fear which interferes with their normal day-to-day life

Prolonged feelings of guilt or responsibility for the death of a loved one

Suffers physical ailments that continue without identifiable medical cause(s) e.g. stomach aches

Reckless and life-endangering behavior to self or others

Organizations that offer counseling support

After identifying adolescents who need further counselling and support, through the administration and parent or guardian they can visit the following institutions:

Amani counselling center and training institute (https://www.amanicentre.org/)

Befrienders Kenya (http://www.befrienderskenya.org/)

Hekima Wellness Center (https://hekima.co.ke/contact-hekima-counselling-center.html)

Activities

Group Activity

Organise the girls in groups of five. Facilitate a session that focuses on the following discussion;

1. What are the causes of griefs in adolescent girls?

2. What are the types of losses and grief experienced in today's world that affect girls?

3. Discuss how the traditional African Communities coped with loss and grief amongst adolescent girls.

4. What were the roles of grandmother's, aunt's in the African set up.

5. Discuss cultural values that guided young girls.

6. Guide the girls to discuss the traditional African responses to disease, death and punishment

Wrap up the group activity by guiding the students in acquiring the following virtues. These virtues help them to be a good support system for those who are undergoing loss and grief:

1. Respect: recognize other girls' rights, status, race, colour and culture.

2. Cooperation: Ability to work together for a common purpose.

3. Love: Deep concern for the welfare of others.

4. Tolerance: Establish strong relationships, ability to bear difficult people or situations.

5. Acceptance: Accept others for who they are, by being non-judgmental.

6. Humility: Being realistic about oneself, recognize one's abilities and weakness and those of others without pride.

7. integrity: Being reliable and dependable, without wavering in moral judgement.

8. Honesty: Being truthful and dealing fairly with others.

9. Perseverance: Determined, and endurance in relationships.

Individual Activity

The Grief Self-Exploration House Activity

This activity is a great way to allow an adolescent girl the opportunity to explore her grief journey in the context of other areas in her life. This activity can be used on an individual adolescent girl; it can also be used in a group setting.

Materials Needed:

Plain paper for each adolescent girl

Drawing pen, markers, colored pencils

Step 1: Outline of house

Instruct the adolescent to draw the outline of a house with the following requirements:

4-story house

A door on the ground floor

A chimney

A flag

You will notice that the adolescent girls will draw different looking houses, this is ok. The house drawn is a good representation of the adolescent girl’s personality, allow them the freedom to draw it without expecting it to look a particular way. Encourage innovation and creativity! Below is an example.

Step 2: Fill in the parts of the house

Instruct the adolescent girl to complete the following parts of the house:

Foundation: Underneath the first floor of the house, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write the values that govern her/their life/lives.

Walls: On the walls of the house, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write the names of people who support her/them.

Roof: On the roof of the house, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write the people that protect them.

Chimney: Coming out of the chimney like smoke, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write ways that she/they expresses herself/ themselves.

Flag: On the flag, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write what she/they want people to know about her/them.

Door: On the door, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write the things that she/they keep hidden from others.

1st Floor: On the 1st floor, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write words that describe her/their grief journey.

2nd Floor: On the 2nd floor, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write things that have helped her/them in their grief journey.

3rd Floor: On the 3rd floor, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write anything positive that may come from her/their grief journey.

Top Floor: On the top floor, instruct the adolescent girl(s) to write a declaration of hope for her/their future.

TALKING ABOUT SELF-HARM AND SUICIDE

“If only you could sense how important you are to the lives of those you meet; how important you can be to people you may never even dream of. There is something of yourself that you leave at every meeting /with another person.”

~FRED ROGERS

Objectives

Describe self-harm and suicide

List different ways of self-harming

Reasons leading to self-harm

Dealing with adolescence who are self harming?

Advance preparation

Study the entire session and ensure that you are prepared and comfortable with the content and activities. Review the questions and activities for this module and take note of the expected responses from the participants. Prepare materials (flipcharts, pens, activity handouts) before the session

This session should take approximately 1hour and 30minutes. Ensure that you will have enough time without distractions Have the girls arrange their chairs in a circle so that you can see everyone and they can all see you. This session can be facilitated by two facilitators who can help each other out. Decide your roles beforehand.

Materials needed

Flipchart or whiteboard/ blackboard

Marker pens and smaller colored pens

Plain paper or printouts of the Body Map

Activity

Emotion Body Map Exercise

Notes

Self-harm is a behavior where someone causes harm to himself or herself as a way to cope with difficult situations or to deal with stress. It can be in the form of cutting, head banging, and punching or even drug overdose. Self-harm acts as a temporary relief but feelings of shame and guilt may follow. It’s an unhealthy coping mechanism for dealing with difficult situations.

The cycle of self-harm

Self-harm may start as a way to relieve pressure from overwhelming thoughts and feelings. This might offer some temporary relief but it does not address or change the underlying challenges that cause these feelings. The temporary relief from self- harm is usually followed by feelings of guilt and shame which causes overwhelming thoughts and feelings causing the cycle to repeat itself.

Some of the reasons as to why adolescents self-harm are:

Difficulties at home

Anxiety

Depression

Peer pressure

History of abuse

Transitions and changes such as changing schools

Refer back to the self- harm cycle and talk about how these feelings fit in the cycle.

Suicide can be described as the act or an instance of taking one's own life voluntarily and intentionally. Adolescents having suicidal thoughts can feel overwhelmed by these thoughts and may feel that they will last forever. Suicidal thoughts are usually an indication of some underlying problems that have caused immense feelings of hopelessness and pain. Someone thinking of ending their lives usually just wants the pain to end.

Warning Signs to look out for:

Ask the girls what are some of the warning signs to look out for that someone might be thinking about or trying to end their lives.

Below is a list of some warning signs of suicide. This is not an exhaustive list and it highlights some of the common signs. Individuals may have other unique signs. Talking about wanting to die

Looking for a way to kill oneself

Talking about feeling hopeless or having no purpose

Talking about feeling trapped or unbearable pain

Talking about being a burden to others

Increasing the use of alcohol or drugs

Acting anxious, agitated or recklessly

Sleeping too little or too much

Withdrawing or feeling isolated

Showing rage or talking about seeking revenge

Displaying extreme mood swings

The power of words

Our messaging and reporting of suicide can be considered unsafe when it contains elements such as romanticizing, glamorizing or detailing the means of death. When this is portrayed in the media and our everyday conversations it can increase suicide attempts and deaths among our adolescents. The language we use should emphasize that suicide can be prevented and treated successfully. It should also communicate the importance of the issue while being careful not to normalize suicide.

Some of the coping methods are:

1. By showing support and not being angry with them, even if you’re confused. Yelling and criticism won’t help and may even increase the risk of continued self-harm

2. It’s also important to face your own discomfort or confusion about self-harming and instead educate yourself about it and why it happens. Then, you can learn about the symptoms, underlying issues, and how to help prevent it from getting worse.

3. Do not judge the adolescent. They already feel distressed and ashamed. Express your care and support, no matter what. Let them know that you’re available to talk about what they’re going through.

4. By creating social relationships as they improve mental and physical health. The more support we have, the more resilient we are. Adolescents who self-harm will benefit from finding people they trust and who show care about what they’re going through.

5. Exercising as it supports mental health and can increase an adolescent’s self-confidence.

6. By letting them express their feelings using creative activities such as writing, participating in art, music or dance classes.

Creating a safety plan

When you encounter an adolescent with such feelings, it is important to immediately seek the help of a psychologist and their guardians to ensure their safety and that of others around them. You can also help them to come up with a Safety Plan.

A Suicide Safety Plan is a set of written instructions that are meant to help someone who is overwhelmed with thoughts of ending their lives. This is supposed to be done with the adolescent and someone that they trust such as their therapist, a friend, family member or a teacher. The Safety Plan should be created when they feel well and can think clearly. It should be kept somewhere that they can access easily should the need arise. The following information should be included in creating the safety plan.

1. When to use the plan- List the warning signs

Help the adolescent to identify types of situations, images, thoughts, feelings and behaviors that cause them to think of ending their life.

2. How to calm/ comfort yourself

Help the adolescent to create a list of activities that are soothing to them when they are upset. These activities are meant to divert their attention to a more positive environment and distract from the negative thought patterns. This second step is initiated when they identify warning signs mentioned in step 1 and it involves coping mechanisms they can do alone before contacting someone else.

3. List people that can be contacted in a time of crisis. Help the adolescent to create a list of trusted people they can talk to if they are unable to distract themselves with self- help measures. If they are in a boarding school, this list can contain trusted friends and a teacher who is close by or the school guidance counsellor.

The list should have names, phone numbers or other contact information. It is important to write it down even if they know the contact information by heart. During a time of crisis, it may be hard to think clearly and remember even basic information.

4. Professional resources. Create a list of professionals that can offer help such as a therapist (if the adolescent is seeing one) or a guidance counsellor if in school.

5. Make the environment safe. Help the adolescent to plan steps to make themselves safe. They can do this by removing items or objects that can be used to hurt themselves or by going to a different location. By removing objects that they can use to hurt themselves, it gives them an opportunity to de-escalate their feelings.

Activity

Emotion Body Map exercise

Instruction:

Bring the girls into a circle, either seated in chairs or on the floor. Guide them in a mindful breathing session. Ask them to sit upright comfortably and come to stillness (as much as they can) with quiet bodies.

Ask the girls to close their eyes or look down at the floor and take a few deep breaths to feel their belly slowly rise and fall. If their minds wander, ask them to gently bring their attention back to the feeling of their breath or belly.

Ask the girls what they noticed and how they feel.

Review the definition of mindfulness:

Mindfulness is paying attention to what is happening in the present moment with gentleness, kindness, and curiosity.

Ask the girls what they paid kind attention to during the practice session. Explain to them that we will be talking about how we can bring kind attention to emotions and how emotions are always changing. Explain that we will also be exploring where emotions are felt in the body.

Name

Date

Emotions Body Map

Instructions: Using the emotions body map below, use different colors to signal each of the different emotions. Show where you feel these emotions in your body using those same colors. For example, “Happiness” could be yellow. If you feel happiness in your feet, then you would color your feet yellow. After you complete your emotions body map, complete each sentence below by stating where you feel certain emotions in your body. Example: When I feel anger, I can label it by saying in my mind, “I feel anger in my chest, and it is red”

Emotions Key

Anger Happiness

Boredom

Love

Loneliness

Gratitude

Sadness

A BRIEF NOTE ON MENTAL DISORDERS

Introducton

As mentioned, adolesscence is a time of various and significant changes . Part of this change is hormonal change that contributes to the physical, behavioral and emotional development that comes at this age. In addition, there are changes in the social environment and changes to the brain and mind (Blakemore, 2019).

Owing to these changes , this period is also the onset of some mental, emotional and personality disorders. It may be difficult to define mental health and mental health problems in adolescents because of the impact of changing subcultures on their behaviors.

In this section we will briefly describe the term metal disorder and highlight some examples of the same that may be seen in the adolescents you interact with. This is no an exhaustive list as there are other factors that contribute to the development of mental disorders other than age.

This list CANNOT be used to diagnose any individual. Instead, treat this as a tool to create your awareness of the existence of mental health problems and possible reasons to refer your students for professional assessment, diagnosis and treatment by a qualified psychologist.

Defining mental disorder

A mental disorder is a health condition involving changes in emotion, thinking or behavior (or a combination of these). Mental disorders are associated with distress and/or problems functioning in social, work or social activities (Parekh, 2018).

Although mental disorders reflect psychiatric disturbance, adolescents may be affected more broadly by mental health problems. These include various difficulties and burdens that interfere with adolescent development and adversely affect quality of life emotionally, socially, and vocationally (Michaud and Fombonne, 2005).

Risk factors during adolescence

Stressful and negative environmental experiences make the adolescent age a more vulnerable period. Aside from hormonal changes and brain development these are some more risk factors that may increase chances of mental disorders in later life.

Adverse childhood experiences such as abuse, neglect and extreme poverty

Being the victim of bullying at school

Hypersensitivity to social exclusion by peers

Parental mental illness

Experimenting with substances such as alcohol and cannabis

Distinguishing normal behavior and mental problems

Adolescents typically have variations in their mood and behaviors as part of the development process and identity formation. These behaviors can be differentiated from serious mental problems by the duration, persistence and impact of the symptoms.

Symptoms or behaviors that might need assessment include;

Signs of overt mood depression (low mood, tearfulness, lack of interest in usual activities)

Somatic complaints such as headache, stomach ache, backache, and sleep problems

Self-harming behaviors

Aggression

Isolation and loneliness

Deviant behavior such as theft and robbery

Change in school performance or behavior

Use of psychoactive substances, including over the counter medications

Weight loss or failure to gain weight with growth

Some more notable mental disorders