7 minute read

3 PLASTER / A FUNCTIONAL METAPHOR

3

PLASTER / A FUNCTIONAL METAPHOR

THROUGHOUT THE 1970S AND EARLY 1980S, plaster would be Neri’s chief sculptural medium, and although he has worked at length with marble and painted bronze since the mid-seventies, plaster is the material with which he is most often associated. It is so crucial to all that he has done with the gure — conceptually and formally — that the terms of his engagement with it bear inspection. First and foremost, the malleability of plaster, which permits an endless variety of additive and reductive techniques, is exceptionally well suited to the concentration and speed with which he typically builds. He can model, carve, or cast it, and its surface, marked by every gesture, each glancing touch of hand or tool, is an unerringly precise palimpsest of the making process. Whatever history may reside in the pose or gestures of the form, the surface belongs entirely to the artist. In this respect, Neri has bene ted from Giacometti’s handling of surface as a viable, personal site of engagement with, and on, a motif that comes sweeping out of the past and into the (his) present moment with its history in tow.

Given its swiftness of application, plaster may be the sculptural medium closest in spirit to painting or drawing, and indeed plaster invites the use of paint. Although Neri has used color on bronze and stone with striking originality of effect, the luminous brilliance of freshly dried plaster can hardly avoid comparison to a waiting canvas, and the possibilities for metaphor quickly multiply when the traditional ground of painting assumes human form.

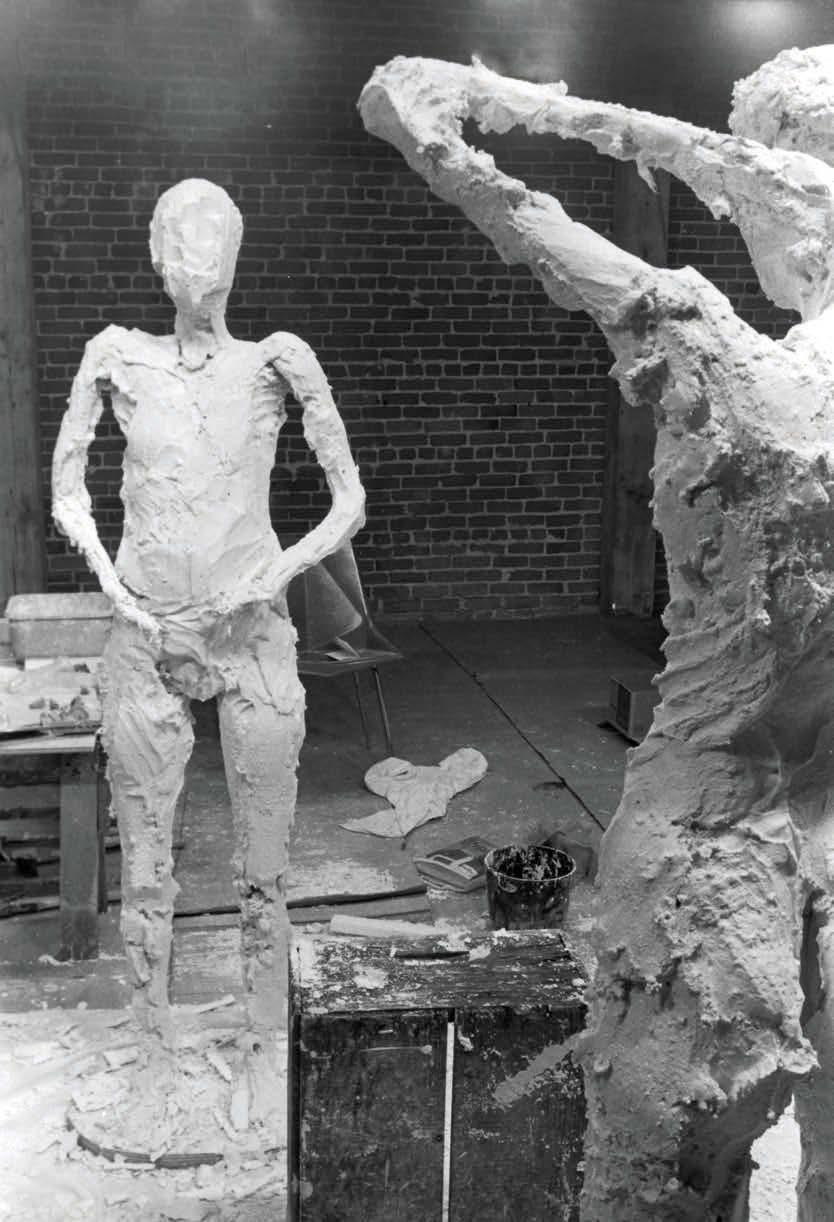

95. Steve Moore, Photographer Benicia Studio, 1980

55

56

Not only does plaster offer the potential for substantial revision — Neri has gone back to individual pieces after years, or decades, to rework ideas — it can discolor or crack over time. Certain textures begin to crumble, as if shedding dead epidural tissue. Thus time enters the work — enters it literally, a material resource just outside the artist’s control — as the sculpture struggles to return to its constitutive state, with often unanticipated visual effects. These kinds of unpredictable occurrences are transformed in turn into a functional metaphor of the patient agency of time — of history — connecting the work both materially and conceptually to the scarred fragments of antique sculpture that Neri rst encountered in Italy in 1961, objects whose surfaces, inscribed by existence itself, gave seductive evidence of historical passage, as a kind of serendipitous artistic presence that very gradually went about altering the work by the means of happenstance and accident.

But this is poetic reading of time and its functional relationship to the work of art. Once Neri recognized the material effects of time as another element active in his work, he forced the point conceptually by taking some of time’s duties upon himself in a series of exhibitions conducted during the early- and mid-1970s, in which he altered and reworked gures on site throughout the period of installation. The rst of these took place in 1972, at the Davis Art Center in Northern California. In this instance, Neri went back to the gallery to work on the sculptures every third night. Two years later, at the San Jose State University Art Gallery, he built a series of gures during the course of the exhibition itself, a performative presentation, and riskier for the artist.

OPPOSITE, LEFT/RIGHT 96. Standing Figure, 1972 Private Collection

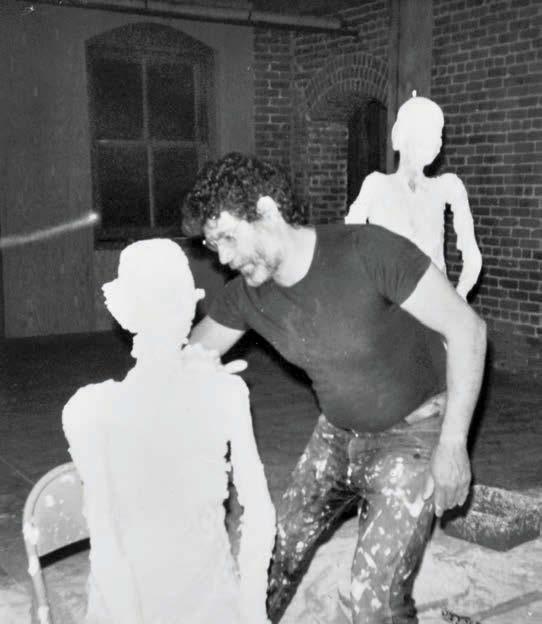

97. Photographer Unknown Neri with sculptures in process, San Jose State University Art Gallery, 1974 98. Photographer Unknown Sculptures in process, San Jose State University Art Gallery, 1974

57

58

These adventures reached a culmination in May 1976, with The Remaking of Mary Julia at 80 Langton Street, an alternative space in San Francisco. Neri was now acting as time’s proxy, its stand-in, even as the project tacitly acknowledged that he himself, and indeed all of the circumstances of setting, are subject to its contingencies in the end. In The Remaking of Mary Julia, Neri and Klimenko returned nightly to the gallery, to the population of gures awaiting them there in various states of completion. Viewers could, if they wished, come each day and follow the changes. Poses were established in part by the sculptures’ steel armatures, so alterations were evident chie y in the realms of mass and surface markings. Yet this in itself was a revelation of Neri’s process, of his innate sense of how the sculptural gure is brought to full formation, day by day. 80 Langton provided a large, unobstructed area in which to build, and daytime visitors also encountered the remnant splatters, pebbles, and dust of the plaster lying around the gures, which stood on the drop cloths that covered the oors. In essence, the gallery offered a window onto the life of the working studio.

99–103. Philip Galgiani, Photographer Sculptures in progress in the exhibition The Remaking of Mary Julia, 80 Langton Street, San Francisco, 1976

59

104–105. Re-making Mary Julia No. 6, 1976 Yale University Art Gallery

The nocturnal encounters — an ongoing discourse, really, between artist, model, and sculpture, intimate, discursive, unpredictable — openly acknowledged the mutuality of exchange through which the work comes into being and the participation of time in that process. Neri’s willingness to expose himself in this way can probably be traced to his early involvement with the Beats, who were generally unconcerned with re nement, nish, or studio mystique — with idea, rather — and who admired the intervention of chance in any artwork. The Remaking of Mary Julia had merged one of the great archetypal forms of Western art with the jazzy modality of the Beats, and its success reveals Neri’s level of formal and material uency at that moment, his knowledge of gural traditions past and present.

60

But plaster had another virtue for Neri: the speed with which it submits itself to his use has fostered productivity, the outpouring of gures from his studio and the gradual spread of those gures into a kind of population. Plaster presented no material obstacles to a strategy of serial building, which allowed Neri to reconsider and then revise one of Giacometti’s most familiar tactics, the incessant cycles of construction, destruction, and reconstruction that were also enabled by the use of plaster. On this point, we can say of both artists that while the sculptural body may ultimately be another object among the world’s innumerable objects, and not inherently conceptual, philosophical, or spiritual, it may accept meaning from any of these areas at any moment, as a gure whose physical characteristics, inscribed and left intact by the sculptor, will inevitably engage its speci c situation or conditions of its setting. The gures are never inactive, never quite lifeless.

106–107. Philip Galgiani, Photographer Sculptures in progress in the exhibition The Remaking of Mary Julia, 80 Langton Street, San Francisco, 1976

61

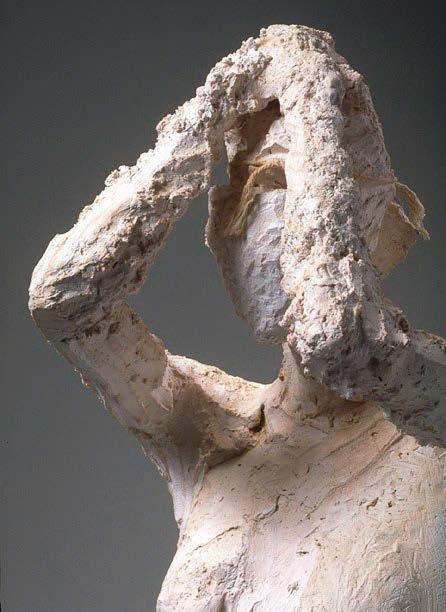

108–110. Sometimes We Forget [Mrs. C. I.] (Detail), 1976 Private Collection

OPPOSITE 111–113. Sometimes We Forget [Mrs. C. I.], 1976 Private Collection

62

Such processes are themselves aware of time, while the frangible material nature of plaster insists, once again, that Neri’s gures will at some point begin to show the effects of time and its vicissitudes, physically as well as metaphorically. It ages, becomes brittle, cracks, or changes color, but now, as we accept such changes as intrinsic to the life of the work, we can see the gure striving to evoke the human capacity for endurance, survival, continuity — how our humanity endures after once-sustaining cultural ideals and iconographies have been discarded, and how we go about seeking replacements for them — with the vertical gure “standing” to present a possible alternative or direction, encouragement, support. The very choice of form declares an underlying optimism. If, at some moment in the future, the sculptural gure no longer has relevance for artists, it will mean that society has undergone a transformation of consciousness, that our understanding of the human, and perhaps of consciousness itself, has changed in ways that cannot be satis ed by the motif.

63