Around here, the arrival of hunting season can seem a little bittersweet.

The sweet part is that so many of us will take to the woods to pursue a passion that is, frankly, a lot more than a “sport.” It’s a way of living and thinking that is still blessedly removed from urban existence.

But I’ll admit, I felt a bit of melancholy while sifting through photos for this year’s Hunting Guide. Why? Because they remind me that hunting and autumn go together, and summer is already waning.

Ah well, the wheel keeps turning, so let’s make the most of it.

We’ve done just that in these pages, assembling some great storytellers to share their experiences in the field, and, more than that, to give us a glimpse into how it feels to hunt in these mountains — and why it’s important to preserve that chance for ourselves and others.

Former Times editor Will Shoemaker argues powerfully that advocacy can be as fun as it is vital. Gunnison native Connor Clark takes us on a wild ride to remind people of a phrase many seem to have forgotten — “fair chase.”

Madeline Thomas returns again this year with news about anthropological research suggesting that women hunters are not the outliers we’ve long assumed them to be. Larry McDonald rolls back time with a story about some of the firstever Gunnison Country backcountry guides.

And don't forget to check out the recipes we've gathered to finish off the hunt with ... dinner!

Enjoy!

12 Q&A with CPW's Brandon Diamond

16 Research reveals a long history of women on the hunt

20 Blue Mesa lake trout busts the recond — sort of

24 A Winchester lever-action and the will to use it

34 Guiding in the Gunnison Country is nothing new

38 Recipes!

Publisher Alan Wartes

Editorial Will Shoemaker Alan Wartes

Madeline Thomas Connor Clark

John Livingston

Nicole Schultheis

Larry McDonald

Alex McCrindle

Bonnie Gollhofer

Photography Marilyn Rodman

Constance Mahoney

Garrett Mogel

Will Shoemaker

Madeline Thomas

Connor Clark

Brandon Diamond

Larry McDonald

Nicole Schultheis CPW

Advertising Sales Steve Nunn

Production Alan Wartes Issa Forrest Hailey Bryant

Online www.gunnisontimes.com

For more information regarding this publication or other special publications of Alan Wartes Media, call 970.641.1414, or e-mail publisher@gunnisontimes.com

Copyright ©2023 No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written consent of the publisher. No part may be transmitted in any form by any means including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without permission of the publisher. Any work (written, photographic or graphic) which the publisher “hired-out” becomes the property of the publisher. Publisher accepts no liability for solicited or unsolicited materials lost, damaged or otherwise.

Cover photo by Constance Mahoney

See her work on Instagram at @cmahoney_wildlife, or contact her at localsofcb@gmail.com. m

Will Shoemaker

Ihad no-sooner cinched down the straps on my meat-laden pack and taken a deep breath before hefting it to my shoulders when I heard a call from the ridge above.

“There he is!” the man said, as I squinted, revealing two human fig -

ures silhouetted on the skyline.

Just in time. Given the poor cell reception where I stood, I wasn’t certain Jared had received my text messages sharing news of success and asking for assistance packing meat off the mountain. Fortunately, Jared and Cameron arrived to help prove the age-old notion: many hands make light work.

The previous three days were a blur. I had shoe-horned a fourthseason elk tag into a busy schedule, book-ended between the Thanksgiving holiday and a big work project that needed my attention first thing Monday morning. Following a nice holiday meal with my wife on

Thanksgiving night — I would have been stuffed, roasted and carved like a holiday turkey had I missed that! — sunrise on Friday found me on the mountaintop battling an army of pumpkin heads.

Like clockwork, fluorescent orange arrived atop every precipice overlooking a good swath of elk habitat at the same time as I did. Hunters drove dark timber where the animals sought refuge, sending elk fleeing in all directions, and provided a constant parade of road-hunting traffic on any double-track open to motor vehicles. This was a “limited” rifle

continued on 6

continued from 5

tag I had in my pocket. No fault of the hunters, crowding reflects regulatory decisions born out of public processes around season dates and length, tag allocation, method of take and other factors.

Over my last 21 years in the Gunnison Valley, I’ve watched crowding become a major inhibitor to a high-quality experience in the woods. It’s not solely the number of hunters, but also the tools at our disposal these days to go ever deeper in the backcountry and sniff out honey holes that in the past required a lot more time and boot leather to find. Between Colorado’s ever-increasing population and recreation and development pressures, public lands and wildlife will only continue to feel the squeeze in years ahead.

Fortunately, conservation and

wildlife advocacy groups are fighting hard to ensure that our public lands receive the protections they deserve, our wildlife populations remain prevalent and that high-quality hunting and the Gunnison Basin will long remain synonymous.

What is advocacy? It’s offering public support for a particular cause or policy. As hunters, gone are the days when we can just show up and expect great hunting. We have to set the table. By that, I mean we have to involve ourselves in efforts to sway law and decision-makers over matters as small as license numbers and as big as access, fair chase and public land protections.

Ben Long, with whom I’ve had the pleasure of working over the last few years through my role in conservation communications, recently wrote a book that captures the challenges before us and lays out a roadmap for

success. It’s called “The Hunter and Angler Field Guide to Raising Hell.”

In the book, Long wrote, “Our society is deciding now whether hunting and fishing will continue to exist, let alone thrive. Everything from hunting seasons, creel limits, access to rivers and lands, quality of habitat — basically our freedom to enjoy the outdoors — is on the block. The future of hunting and fishing depends on habitat and access. But in modern America, those crucial ingredients of any good day afield do not exist by accident. They depend on conservation. And conservation depends on politics.”

Politics? If you’re anything like me, you probably venture afield to escape that kind of thing, yet the reality of the matter is that political decisions shape our lives. I’m fortunate to have

Will Shoemaker is pictured following success on a 2022 elk hunt in the Gunnison Basin. (Courtesy Will Shoemaker)Our hospital includes a fully-staffed eight bed emergency department which provides emergency care 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

For treatment of your minor injury or illness that can’t wait for a doctor’s appointment.

a front-row seat to some of the politics that affect hunting and angling in the Gunnison Basin through my role on the board of Gunnison Wildlife

Give money. Give time. Get involved. Educate yourself about the issues. Write letters. Share your thoughts with elected officials and other decision-makers. Be a voice for our rich wildlife resources and hunting traditions. Put your skills and interests to use. Every little bit helps.

The Gunnison Basin is one of Colorado's last strongholds of wild country, with large swaths of protected public lands, plenty of good forage and stable wildlife populations. As a result of these factors, I was able to sniff out a spot last fall that wasn’t overcrowded with hunters, harvesting a bull on the last morning of the hunt that two friends helped pack out of the high country, strengthening each of our connections to these wild places that give us life in so many ways. Persistence paid off.

It will also take plenty of persistence to ensure that wild places remain this way and our hunting traditions are preserved for generations to come. j

Association (GWA). I’ve learned thatsuccessful conservation advocacy can be a blast, not unlike hunting. The objectives may be different, but the need for preparation and wellexecuted strategy bears a great deal of similarity.

For the last 25 years, GWA has accomplished much for the Gunnison Basin's rich wildlife resources. This year alone, we have volunteered our time on habitat improvement projects, submitted comments on the Colorado Wolf Restoration and Management Plan, hosted a Big Game Herd Update presentation by Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW), provided feedback to CPW on big-game season dates and license limitation and hosted fun social gatherings. We’re closely engaged in myriad issues and public processes directly affecting our wildlife resources, from herd management plans to wildlife migration corridors to forest plan revisions and new proposals to protect public lands.

All of this can seem daunting. I get that. But each of us can play a role. What can you do to help the cause?

(Will Shoemaker is a professional communicator in wildlife and public lands conservation and former editor of the Gunnison Country Times . He serves as secretary of the Gunnison Wildlife Association Board of Directors.)

The Gunnison Wildlife Association (GWA) is committed to protecting and enhancing the health and sustainability of wildlife and public lands in the Gunnison Basin. GWA envisions a future in which wildlife populations and their habitat are diverse, secure and thriving, that recreation on public lands occurs responsibly and that impacts to wildlife and the environment are minimized. Follow GWA at facebook.com/ gunnisonwildlifeassociation or instagram.com/gunnisonwildlifeassociation and contact us at gunnisonwildlifeassn@gmail. com.

“I’ve learned that successful conservation advocacy can be a blast, not unlike hunting. The objectives may be different, but the need for preparation and well-executed strategy bears a great deal of similarity.”

Will Shoemaker

remaining strongholds of wild country and abunare fighting hard to ensure it remains that way.

SIGHT-IN DAYS 2023

Where: 881 County Road 18, Gunnison, CO

When: Oct 11, 12, 13

Oct 25, 26, 27

Nov 8, 9, 10

Time: 8 a.m. -4 p.m .

Cost: $10.00 per gun

Raffle Tickets can be purchased at Sight-In Days.

Raffle Proceeds go to Scholarships, Youth and Women Firearms Safety Training, Youth Trap League, 4-H and Boy Scouts Shooting Programs, Hunter Sight-In Days, and Range Improvement.

Only 400 tickets available

$20 per ticket $50 for 3 ticket Need not be present to win

THREE PRIZES – THREE WINNERS

Christensen Ridgeline

6.5 Creedmoor Rifle

Mounted with a Vortex Crossfire II Scope

WINNER’S CHOICE

Colt King Cobra: .357

Double Action

Revolver, 3” Barrel

Springfield Armory

Hellcat Micro 9mm Pistol

Draw Date: November 10, 2023, 4:00 P.M. Gunnison Sportsmen’s Association Rifle Range, 881 County Road 18, Gunnison, CO 81230

www.gunnisonsportsmens.com

Garrett Mogel

The eyes of a great horned owl never move. Their necks are designed to rotate up to 270 degrees.

T-SHIRTS:

By the time Brandon Diamond started his freshman year as a biology major at Western State College (now Western Colorado University) in 1996, he already knew the career path he hoped to take: wildlife management in Western Colorado. For most people, dreams like that are just a starting point, not a road map. But nearly a quarter century later, as Gunnison-area wildlife manager for Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Diamond can say he’s done exactly what he set out to do.

I recently had the opportunity to sit down with Diamond in his crowded office on West New York in Gunnison — just a few yards away from a brand-new facility that’s currently under construction. We talked about his background, the changes he’s seen over the years and what the future holds. (The following Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.)

What made you so certain at a young age that you wanted to pursue a career in wildlife management?

My dad was a really avid hunter and fisherman. I actually grew up near Nederland, which today is a madhouse, but in those days was a pretty wild, remote part of the state. I had some amazing experiences as a kid and those just stuck with me. I mean, that was my passion. That's why I came to Western. I used to come here with my dad when I was a little kid to elk hunt in the 80s. I remembered it and knew Western was here. I'm grateful to be in this community where wildlife is still on the front burner and a high priority. It's a good place to work and a great place to have invested so much of my professional career.

In that time you’ve seen a lot of changes. How would you describe the difference between now and when you began?

I'm not sure what the human pop-

continued on 14

ABSOLUTELY STUNNING 2800sf home at the end of the Ohio Creek valley sits on 40 acres with Carbon Creek running through the acreage. Custom home & garage offer in-floor heat, 3 bdrms/3 bath, south facing windows with incredible views and a 4 car garage with work space & a walk-in cooler. 3750 County Road 737; $2,500,000.

MOUNTAIN HOME with loft nestled in the trees with Gold Creek in the back yard on over 3 acres. Just 3.5 miles from Ohio City, 1 bdrm/1 bath, bordered by national forest, built in 1994 with well & septic. 1,008 square feet with generator and shed too. 3491 County Road 771; $635,000.

BREATHTAKING VIEWS of Blue Mesa

Reservoir from this 3 bdrm/2 bath, 1620sf home with 40 x 26 garage and 14 foot garage door for your boat to park next to the fish cleaning station in the garage. Bunk house above the garage sleeps 6 in the 2 bdrms & half bath. 33000 State Highway 149; $385,000.

ulation in Colorado was in the 70s when I was born, but it certainly was less than it is now as we approach 6 million people, and you can feel that. There are just more people moving to these places that are sort of pivotal and integral to the future of wildlife conservation. At the end of the day, it all boils down to how much functional, quality, intact habitat are we going to leave for wildlife, because that's what's going to determine the future of our wildlife resources. If we have that in perpetuity, we will have functioning wildlife populations in perpetuity. The concern for someone like me, who's been in the business for quite a while and grew up in Colorado, is that it's changing at such a rapid rate. People honestly want to be everywhere all the time and that's not necessarily compatible with longterm wildlife conservation. We can't continue to do everything we want and expect wildlife to thrive like it did five or 10 or 20 years ago.

Are you particularly talking about the encroachment of new development?

Yes, development, but also just human use across the landscape. It's not necessarily just building new houses, it can be building new trails, climbing fourteeners and building new campgrounds and more water-

based recreation. All of those things impact wildlife habitat. I try to be fair about it, and just to continue to elevate wildlife as a topic of conversation. We're making conscious choices: Will wildlife be a priority? What concessions are we willing to make as we tip that balance more and more with our land use? I think a lot of folks are starting to realize that we need to have more of a sustainable mindset and understand what our capacity is and that our carrying capacity is not only for wildlife habitat and wildlife, but also for all of the other things we want to do as a community.

Where do hunters fit into the conversation about resource conservation?

Hunters and anglers are an interesting group because they pay for a large portion of the wildlife management and conservation activities that happen across the landscape (through license fees). If a kayaker goes out on the Gunnison River and sees a great blue heron or a moose crossing the river, hunters and anglers are paying for a lot of those opportunities that non-hunters and anglers enjoy. Hunters do have a significant short-term impact on the landscape while they're here. We're always encouraging them and trying to teach a high ethical standard, where you show up and have that

sort of stewardship ethos of, ‘Okay, this is a wonderful privilege that I have to be here. I'm going to enjoy it, but I'm going to take care of the land, I'm going to leave a clean camp. I'm going to learn and understand travel management restrictions. I'm going to be courteous to non-hunters and anglers, all of those things.’

How has CPW’s definition of good habitat stewardship evolved? What’s the current state of thinking?

In our hierarchy of land use, it's focused on ‘avoid, minimize, mitigate.’ If something is proposed that is just simply incompatible with wildlife in that area, we ask ‘Can we avoid it? Can we do without it?’ The next tier would be to minimize. ‘If you're going to do something, do you need that much?’ Then the last one is, ‘Well, it's going to happen, how do we mitigate the impact to the best of our ability? We've always operated within that mantra, it's just that the volume is more now and the intensity is more now. It's getting harder to mitigate the volume of land use that's happening all at once. When you look at one impact in this one geographic area, it's easy to forget that there are 50 others going on at the same time. When you look at things cumulatively over the next five or 10 years, what's going to be left? We have to have that broader mindset as well to do our

best due diligence for wildlife, especially when we're planning in terms of habitat protection and conservation.

Yet planning isn’t concentrated in any one place. How do you deal with so many different agencies and entities and still get things done?

Folks are starting to learn that Parks and Wildlife is not really a regulatory agency. When it comes to state lands that we manage, we'll do whatever is right at our discretion on those properties. But when it comes to federal land management, county land management and private land management, we often just serve as an advocate in an advisory role. We present our case. We put things on the table. Oftentimes, it's not us making the ultimate decision, so we try to do our due diligence, do our best and put our best foot forward, knowing that outcomes are not necessarily certain. l

(Alan Wartes can be contacted at 970.641.1414 or publisher@gunnisontimes.com.)

It’s 3 a.m. and as I jostle back-andforth in the side-by-side, I remind myself that this will be the coldest part of the day. I am bundled-up, sitting in the passenger seat, half asleep, clutching my piping hot mug of coffee. My partner and I travel for an hour before reaching the trail head. I am anxious to begin hiking. We turn our headlamps on to the red light setting and gently situate our gear. The snow from last night has sent the forest into a calm surrender, perfect for bull hunting. The only noise comes from us, the humans breaking the silence.

Two other OHVs pull up to us. They are friends of ours, also hunting the same unit. After some casual banter, we wish each other luck and take bets on who will have the first bull down this year. Every year I am told that I get the first shot. Being the only woman in the group, this attempt at chivalry doesn’t surprise me. If only hunting were that predictable. I mark a waypoint on my maps, and we depart into the sea of aspens and scrub oak. It’s the last hour of darkness, and the sunlight is starting to kindle in the western sky.

I quietly take one step after another and slowly get into rhythm. The morning sounds and smells heighten my senses and awareness. I find a perfect place to rest, glass and patiently wait. As I sit and look at my mountain views, I feel at ease and at one with the land, my home. I begin to think about my relationship to hunting and why I am often the only female in my group.

Like most of us, growing up, I was taught that women were the gatherers and men were the hunters. My inherent kinship with hunting forced me to further ponder why this connection as a modern woman feels unique. Perhaps it is because hunting is not merely a pastime or sport, it is a part of my DNA, going back thousands of years.

A recent article published in PLOS ONE, examines 63 different foraging societies and finds that 79% of those have documented proof of female hunters. Archaeologists determined

continued from 13

that anywhere from 30-50% of the big game hunters within these societies could be female. According to an article published in the New York Times on Aug. 1, 2023, this study has compelled scientists to reexamine discoveries from burial sites where they concluded that, nearly 10,000 years ago, big game hunting was a gender-neutral method of sustenance. The study in PLOS ONE implores us to reevaluate archaeological evidence through a different lens.

At the end of the day, this makes sense. The more people who contribute to the overall good and sustainability of the group, the better off the community will be. When survival is your number one priority, it’s allhands on deck. It is logical that our ancestors, men and women alike, shared in the frequent responsibility of providing the main food source. We can only speculate as to how these ancient societies lived their lives. I am confident that technologi-

cal advancements will provide more insight over time.

Regardless of gender, hunting is a major part of our human evolutionary tale. Knowing the history of my hunting female ancestors brings me joy when I am out in the field. Hunting has taught me discipline, confidence, accountability, how to fail and has been the most fun and memorable experience of my life. My curiosity is mostly satisfied for now, because I know that this deep-seeded feeling is genuine.

The first snowy mornings of the year are especially quiet. Scavenger birds, ravens, crows and magpies hover closely by, knowing the carrion they get to feast on if I succeed. I watch them. They mock me as if they know I have my doubts. Four long days pass, each with more miles, more views and more disappointment. My legs hurt, but I am more concerned about my mental strain, which is reaching its threshold. After many miles and facing defeat, my partner and I decide to relocate to the other side of our hunting unit. At

the time, we have no idea what a fortunate decision this will be.

It’s noon on closing day, so there is no time to lose. We hike swiftly up the gut of a dried-up drainage. We reach the rolling hills that surround the bowl of the ridge where shelves of meadows and sporadic trees are known to hide big game. The snow from a few days before has come and gone, and the ground is soft and forgiving.

We make eye contact and I am reminded to stay calm, keep quiet and be watchful. That’s when I see him, a bull, a 5x5 bull, and my heart skips several beats. My training kicks in, and I settle down prone and fire a round. I immediately rechamber and fire another round. That’s when I hear, “He’s down,” and I can hardly believe what I have accomplished: my first bull elk.

I am ecstatic! i

(Madeline Thomas is a born-andraised Gunnison County native with a passion for all types of hunting and fishing.) Thomas enjoys connecting with her ancestral roots while fishing.

Foxes use the earth's magnetic field to their advantage when tracking prey in tall grasses.

In the early morning hours of Friday, May 5, as the springtime mist drifted over the Blue Mesa Reservoir, a local father-son duo set out in their fishing vessel. It was opening day for boating access, and the reservoir bustled with excitement as anglers put-in.

Scott Enloe and his son, Hunter, began scanning their sonar for telltale signs of massive lake trout as soon as they reached open water. When a gigantic spot appeared on the screen a few hours later, nobody could have predicted the size of the monster swimming beneath them.

Upon capture, the trout weighed 73.29 pounds, smashing both the state and world records. But there

was a problem: to be official, the fish would have to be taken and measured on land. Instead, Scott happily released it. Now, it is unknown if the Gunnison man will ever receive the official record.

Hours earlier, waves lapped up against the hull of their fishing boat as the Enloes cruised the inlets of Blue Mesa Reservoir. The pair have dedicated years to studying lake

trout, and have memorized feeding locations where massive fish thrive. Their strategy seemed to be effective as Hunter, who works as a fishing guide for Alpine Outfitters and Sportfish Colorado, had already reeled in a 31-pound lake trout when a historicsized mark lit up the sonar.

“Thirty pounds is a huge fish, it's trophy quality for anyone,” Scott said. “We were looking at big ones on the screen, and then the monster fish showed up, and it was three times the size of the others. It made a nosedive for my jig, my line moved, and I set the hook.”

mated to be 60 years old — as long as the Blue Mesa has been there, that fish has been in there. I can only imagine how many eggs that fish has laid over her 60 year period, and how many fish she has produced. I’m not going to be the one to end that cycle.”

Even though Scott may never receive an official record for his prized catch, the weight would easily break the state record of 50.5 pounds and the world record of 72 pounds, achieved in Canada in 1995.

For the Enloes, the historic morning acts as another crowning achievement in their fishing careers. While he has only lived in the Gunnison Valley for seven years, Scott has been fishing Blue Mesa since 1992, and Hunter spent the first years of his life growing up in Almont. The two have been hunting and fishing together even before Hunter could walk.

Since then, Hunter won three youth fly fishing world championships. The duo also set a record for being the first father and son to represent the United States on the men’s and youth fly fishing teams at the same time.

Scott said he is still in awe of that special morning.

“We were just in amazement and we just sat in the boat and floated along and just laughed,” he said. “I’m not going to kill the fish just to get a piece of paper on the wall that says ‘Hey, that’s the largest one in the world.’ If I don’t get that paper, I’m fine with it, because I can go to sleep tonight knowing that fish is alive and well, swimming around in the Mesa.”

Update: As of August 14, there had been no application for the state or world record, according to aquatic biologist Dan Brauch at Colorado Parks and Wildlife. s

(Editor's note: This story first appeared in the May 25, 2023 edition of the Gunnison Country Times.)

(Alex McCrindle can be contacted at 970.641.1414 or alex@gunnisontimes.com.)

The behemoth swallowed the jig and rocketed to the surface. Scott maintained control, preparing for the fish to plunge back to the bottom. The reel hissed as the trout dragged heaps of line with it, returning to a depth of 40 feet. After a back-and-forth battle between the seasoned fisherman and gigantic trout, the two men hauled it aboard.

The nearly 74-pound fish was 47 inches long, numbers that would break the world record for largest lake trout ever caught. However, after the duo measured and weighed the fish aboard their boat, they released it back into the lake — an action that could prevent them from receiving the official record.

For record applications, the State of Colorado and the International Game Fish Association have requirements that each angler must follow. The two most important are killing the fish and weighing it on land — not in a boat.

“Who am I to kill that fish?” Scott said. “According to officials, it is esti-

“If I don’t get that paper, I’m fine with it, because I can go to sleep tonight knowing that fish is alive and well, swimming around in the Mesa.”

Scott Enloe

It’s a scene nobody recreating on public lands across Colorado wants to run into: an abandoned campsite full of trash and, worst of all, human waste.

The slogans “Leave No Trace” and “Pack It In, Pack It Out” have been uttered countless times across all types of recreation groups. Yet every year, organizations across Colorado partner together to pick up trash and clean up public lands left littered. For one organization, the removal of makeshift toilets from hunting camps has become far too common.

“We get a lot of stuff out of the backcountry — human waste, dog waste, lots of toilet paper, micro and macro trash and lots of leftover camping gear,” said David Ochs, executive director of the Crested Butte Mountain Bike Association, which operates the Crested Butte Conservation Corps (CBCC) as its trail care and stewardship team. “Sometimes we need to really tend to the ‘waste’ of it all — not fun, but we have some stellar crews committed to the ‘duty.’”

Ochs said that his stewardship crew has collected an average

of 1,138 pounds of trash each year since its formation in 2017. In 2023, the team has already moved 1,177 pounds of trash, evidence that the problem is growing.

The group has decommissioned 88 illegal fire rings and collected 54 human waste piles. They clean up around three makeshift toilets left in the wilderness each year.

“It’s amazing the extent to which some people go to create luxury and creature comforts deep in the backcountry,” Ochs said. “But it’s a shame that some have no remorse in leaving it behind.

A luxury commode at an abandoned hunting camp. (Courtesy Crested Butte Mountain Bike Association)

A luxury commode at an abandoned hunting camp. (Courtesy Crested Butte Mountain Bike Association)

What gets us is the extent to which some users really go out of their way to do the right thing and then the amount of users who completely neglect or are naive to basic backcountry etiquette. Not all of it is malicious, oftentimes it’s truly ignorance. The toilet problem is an ugly one in that users go out of their way to plan and make this device, then have no remorse in leaving it behind, often in truly glorious backcountry settings.”

Colorado Parks and Wildlife Area Wildlife Manager Brandon Diamond thanked Ochs and the CBCC team for the work they’ve done and challenged hunters to leave no toilets behind this season.

“As hunters, we have the special opportunity and privilege of enjoying our public lands and wildlife resources,” Diamond said. “We should set the standard in terms of land stewardship, and provide an example to public land users on how to keep a clean camp and responsibly recreate … Hunters need to do their part.”

There are several portable toilet products on the market, many of those specifically branded with hunters in mind. Using and cleaning a “groover” toilet is simple, and many towns across Colorado have services affiliated with businesses that will clean a portable toilet for a fee.

For those not interested in a portable toilet option, there’s another solution.

“At the very least, everyone can use a wag bag and pack it out,” said CPW Senior Wildlife Biologist Jamin Grigg.

Ochs said his team is proud to clean up their backyard and maintain roughly 70 miles of trail and open space every year.

“We need to continue to educate all visitors and users,” he said. “Hikers, bikers, hunters, anglers, motos, runners, birders and flower junkies — pros and newbies — we all make an impact, but we’re obligated to leave no trace.” u

Icome from a long line of gunsmiths, antique gun collectors and overall gun fanatics. Since I was very young, I have been exposed to antique Winchesters and all of their glory. To this day, I pick up a 150-year-old rifle in perfect (but well-used) functioning condition and day-dream about the stories they could tell if they could speak. Did this gun find a perch on a high canyon wall, liberating a family or tribe from evil-doers trying to take over a family homestead? Or was it in the hand of one evil-doer raiding a wagon train rolling down the Oregon Trail headed west?

At Trader’s Rendezvous in Gunnison, we have bought rifles made in the late 1800’s with tally marks carved into the stock. To the best of my knowledge, those marks do not represent elk or deer taken with the rifle, but something much more sinister. Once, we purchased a Winchester found in the desert in Arizona, where someone leaned it against a tree and never returned to pick up the gun. Was he captured or killed? Or did he just forget where he laid it? It was found 100 years later, with the twisted old cedar tree growing around the rusted-out barrel. To me, these guns represent the epitome of the American West — a rifle that helped carve out my existence in this very valley here today.

I have been bowhunting for almost a decade, and I have gotten addicted to getting close. With every step I gain on my prey, my heart feels like it is increasing 10 beats per minute. I want to be so close that the palpations of my heart are almost at an audible level. The hunting “game” does not even begin until I get under 60 yards, and that’s where the fun starts. Every little barefoot step I inch forward, the stakes grow higher and the adrenaline rush gets more intense.

There is little in this world that rivals the mental intensity of spot and stalk archery. It is one-on-one, my predatory skills against my prey’s keenly adapted ability to simply sur-

vive. No radios, no trail cameras, no tree stands; just a barefooted guy with a pointy stick against a perfectly adapted animal, whose sole purpose on this planet is to evade predators and pass on its genetics, just as its species has done for thousands of years. It is a primal game and a story as old as the dirt I trudge across in search of my prey.

I grew up a rifle hunter, so when I decided to pick up a bow in college, I was the first in a long line of Clark hunters to attempt to take my prey with archery tackle. The journey has been difficult, with a lot of hard lessons along the way, but with the incredible hard-headedness I possess that no doubt comes from my Clark side, I have found success. I have taken several elk, several mule deer, a pronghorn, a bear and a bighorn sheep with my bow — each a Pope and Young record book representative of their species.

Once you feel the adrenaline rush

impersonal and disconnected. The last bull I shot with a rifle was in 2007 with my dad when I was 14 years old.

The day before my season, I went to a spot where I’d had archery success in the past. I was deep, it was remote, and to my surprise and dismay, I got my tail kicked for two days. I never came across any elk or any fresh sign. It was time to regroup and make a new plan. On day three, I made a long trudge through an area unfamiliar to me. When I reached the top, I had yet to see or hear any elk. I found a comfortable perch in the shade of a spruce tree to eat some jalapeno cheddar deer sticks leftover from my successful archery deer hunt the month before.

After having not rifle hunted for many years, I began to realize that it is not quite as easy as I had made it out in my head to be. I had set out in search of a big bull, saying I would pass raghorns if I had a shot. I had not even had an opportunity at a spike, let alone a 6-point bull. I ate a nice slice of humble pie as my previous success had blinded me to the fact that rifle hunting elk was still difficult. Humble pie is a meal that is always served to you when you need it most.

that comes with a sub-30-yard shot on an animal you have been chasing for weeks, the thought of going back to hunting with a rifle seems bleak, but I always tell people that I will hunt with any weapon you give me. “Give me a slingshot and a tag and I’m going to give her hell”. That was the case in 2022.

I lucked into a rifle bull tag and I was without question going to hunt it. As I was visualizing my hunt to come, all I could picture was myself sitting on the other side of a canyon 500 yards away from a bull, with my modern day rifle that is more than capable of making that shot. It felt

As I was lost in thought, I heard the rumbling sound of a herd of elk barrelling right in my direction through the shale. I fumbled for my Weatherby rifle and scrambled for a solid rest knowing they would be on top of me in an instant. The herd ran into 75 yards of thick, deep timber and stopped on a dime, catching my wind. I saw tines on a bull as they wheeled and ran further up the mountain away from me. I never had a good look, a lane or a shot. I let out a few cow calls, hoping they would at least stop and give me a lane to shoot. They did not. I “still hunted” the timber the rest of the day, following tracks as they made their impressions in soft dirt and pine needle beds on their way out of the country, but never bumped into them or saw them the rest of the day. When I made it back to my vehicle, I knew I needed to ask for another set of good eyes, and that’s what I did.

continued on

“No radios, no trail cameras, no tree stands; just a barefooted guy with a pointy stick against a perfectly adapted animal.”

The morning of day four is a day that I will remember for the rest of my life. With the help of fresh eyes on the landscape, my comrade glassed up a 6-point bull with nine cows that were way too far away to make a morning approach and make it in time — but I had a plan. Diligently, I watched them. As the temperature started to rise and the sun got higher, I knew it was time for them to find a daybed. When they disappeared in a patch of timber around 9 a.m., and I hadn’t tracked any other movement in the trees, I figured they had found a good, shady place to take their mid-day siesta. Now, we had a waiting game … or did we? I had a plan. It may have been hair-brained, but it was a plan

nonetheless. I hiked back to my vehicle and headed home to grab a gun I had always dreamed of shooting an elk with — a Model 71 Winchester lever-action with Buckhorn open sights and chambered in a .348. — an elk-killer cartridge from years long gone.

As I pulled the old relic from the safe, I called one of my best friends and told him to meet me and bring his big glass. After a brief mission meeting, we knew the plan. He was in a position to see if I bumped the elk out and to keep an eye on them for another stalk the next day. I made my way to the start of the planned route with a stout 10 mph wind in my face to cover my scent and my (hopefully)

minimal noise as I visualized my slow approach.

When I reached the top of the ridge, I kicked off my sneakin’ shoes. They are quiet, but nothing is as quiet as good-old stocking feet. A hundred yards before I hit the edge of the timber patch, I racked the lever, shoving a .348 caliber, 200 grain chunk of copper covered lead into the 100 year-old chamber. I released the hammer and then brought it back to half-cock and the game began. I did not know exactly where they bedded, so with each soft step I took, my heart fluttered as every one of my senses heightened to an almost supernatural state. I smelled elk, but I heard

bull of the herd as he bugled and rose from his bed 25 yards beyond the cow. I then heard the sound of his trot, making a beeline to my location. I settled the gun on the downed log in front of me and went to full cock as he came into view. 40 yards, no shot. 30 yards, 15 yards, no shot. He never broke his smooth gait and rapidly approached my foxhole. He made a slight change of direction up the hill, trying to come above me to get my wind. When his head went behind a small spruce, I switched the rifle to the other side of the log, and I knew this was the spot. 12, 10, 6 yards, moving quickly right to the location of the cow calls.

He stopped right in front of my muzzle, just four yards away. As if it were in slow motion, I let the 100 year-old gun bark. The hammer slammed down sending the firing pin right into the primer, releasing 200 grains of elk-killer through the top of his heart. Years of hunting and shooting chipmunks with lever action rifles, my instincts took over as he wheeled to run straight downhill. I stood, simultaneously racking the lever again to send another bullet an inch above the original, and he crashed, expiring before his head hit the ground.

and saw nothing but the wind and its effects.

I would make a 25 to 40-yard stalk, find a shaded spot and survey the scene for at least five minutes before I made the decision to keep pushing forward. This happened four or five different times before I made the final approach to where I knew they had to be. I’d made two steps on my final approach when I saw a cow stand up on high alert 30 yards away. I froze in my tracks. She couldn’t smell me, but she knew something wasn’t right. Thousands of years of being chased by humans and other predators made her instincts tingle as she stood facing my direction. She made a couple of steps to turn and separate herself from presumed danger. As soon as she broke her gaze, I hit the deck and released two soft cow calls from the diaphragm in my mouth.

I got an instant return from the

After a primal yell of success and the adrenaline dump that always follows a kill, I did what I was taught from a young age to do. I removed my hat, put my hand on the animal and sent a prayer up, thanking it for its life, for a quick and clean kill, for my ability to do what I love to do, for friends and family who help and for a meat resource that will keep my family fed for the next year until I am able to do it again.

I’d finally done it. I had always wanted to take an animal with an open sight Winchester, and that day it happened as if it were a movie script. Truly, it was an accomplishment of a lifetime and a story that will hopefully be passed down to many Clark hunters of future generations.

You can take the bow from the bowhunter, but you can’t take the bowhunter out of the man. h

Pizza, Calzones, Pasta, Strombolis, Burgers, Sandwiches, Salads and much more!

Proudly serving Colorado craft beer

(Connor Clark is a Gunnison native and member of the family-owned business Trader's Rendezvous.)

(Connor Clark is a Gunnison native and member of the family-owned business Trader's Rendezvous.)

“My heart fluttered as every one of my senses heightened to an almost supernatural state. I smelled elk, but I heard nothing but the wind and its effects.”

Each year, hunters in the field encounter black bears and mountain lions and, in rare instances, must be prepared to defend themselves from an aggressive animal. It is important for everyone recreating in Colorado to know how to react and understand the warning signs a large predator may send their direction.

Here is a closer look at the warning signs and what you should do if you encounter a bear or mountain lion while on a big-game hunt.

Colorado is home to an estimated 17,000 to 20,000 black bears. While aggressive behavior is rare, bears may be unpredictable, and there have been three documented bear attacks on a human in Colorado in 2023. With that said, experience has shown that the majority of conflict with wild bears is avoidable. For hunters, that starts with keeping a

clean campsite.

“Unsecured food and trash remains the leading cause of humanbear conflict,” said Colorado Parks and Wildlife Area Wildlife Manager Brandon Diamond. “Maintaining a clean camp and securing food away from camp is the best way to keep bears away from your campsite.”

“For successful hunters, meat management at camp is also a good thing to think about,” he said. “If you can hang your meat out of reach of bears, that really helps. We seem to have instances every fall where a bear drags a quarter out of camp, which leads to problems for the hunters and bears. The last thing we want is for wild bears to associate hunting camps with food rewards.”

When encountered in the wild, black bears are usually wary of humans and will look to turn and go the other way. For those without a valid bear hunting license in their pocket, if you find yourself in close quarters with a bear, or happen across a bear on a food source — such as an elk or deer carcass —

simply back away or give them plenty of room to escape. Wild black bears seldom attack unless they feel threatened, cornered or are provoked. Many hunters carry bear spray these days, which is proven to be an effective, non-lethal tool in many conflict situations.

If you surprise a bear on a trail: Stand still, stay calm and let the bear identify you and leave. Talk in a normal tone of voice. Be sure the bear has an escape route. Never run or climb a tree. If you see cubs, their mother is usually close by. Leave the area immediately.

If the bear doesn’t leave:

A bear standing up is just trying to identify what you are by getting a better look and smell.

Wave your arms slowly overhead and talk calmly. If the bear huffs, pops its jaws or stomps a paw, it wants you to give it space. Step off the trail, keep looking at the bear and slowly back away until the bear is out of sight.

If the bear approaches:

A bear knowingly approaching a

person could be a food-conditioned bear looking for a handout or, very rarely, an aggressive bear. Don't concede to this behavior: instead, stand your ground. Yell or throw small rocks in the direction of the bear. Get out your bear spray and use it when the bear is about 40 feet away.

If you’re attacked, don’t play dead. Fight back with anything available. People have successfully defended themselves with pen knives, trekking poles and even bare hands.

Mountain lions

Colorado is also home to an estimated 3,000 to 7,000 mountain lions, with studies ongoing around the state to get a better understanding of their density. One such study is currently being conducted in Gunnison.

“Mountain lions are rarely seen but are common throughout western Colorado,” said CPW Senior Wildlife Biologist Jamin Grigg. “They prey primarily on deer and elk and are likely to be present anywhere deer and elk are abundant. They are generally shy around humans but are also very curious, similar to house cats.”

Mountain lion attacks are relatively rare. There have been 25 known attacks of a mountain lion on a human in Colorado since 1990. Oftentimes, protective behavior by a mountain lion can be mistaken for predatory behavior.

Grigg said mountain lions are ambush predators, meaning they rely on stealth and secrecy when hunting.

“If a lion allows you to see it, it’s likely not acting in a predatory manner,” he said.

What is observed more commonly is protective behavior by mountain lions when they make an effort to direct a human away from a food source or their young kittens. Protective behavior can include bluff-charging — in which the lion will behave aggressively by walking toward a person and gesturing with its paws while vocalizing. Report aggressive bears mountain lions to the nearest CPW office. The Gunnison office can be reached at 970.641.7060.

(John Livingston is the public information officer for the southwest region of Colorado Parks and Wildlife.)

Archery

Deer, Elk, Bear: Sept. 2-30*

Pronghorn: Aug. 15-Sept. 20*

Moose: Sept. 9-30

Muzzleloader

Deer, Elk, Bear: Sept. 9-17*

Pronghorn: Sept.-21-29

Moose: Sept. 9-17

Rifle

Sept. rifle (bear): Sept. 2-30*

1st rifle (elk and bear): Oct. 14-18

2nd rifle: Oct. 28- Nov. 5

3rd rifle: Nov. 11-17

4th rifle: Nov. 22-26

Plains rifle (deer): Oct. 28-Nov. 7

Pronghorn Antelope: Oct. 7-15*

Moose: Oct. 1-14*

*unless otherwise noted in CPW hunt code tables (Photo by Garrett

The Gunnison Sportsmen’s Association (GSA) changed my life. I have lived in the valley for close to twenty years, but I had some nervous phobias around firearms, and for whatever reason the problem seemed to be getting worse. I grew up in a hunting family and was raising two young boys who seemed to share the same passion. I knew I had to do something to remedy the problem. Running from an issue is never a good option.

I decided I had to face it and called Rick Odom, a board member at GSA. He kindly offered to show me what bullseye pistol is all about. Several other members were there and they graciously took me under their wings. They allowed me to shoot, but not before thoroughly explaining safety as well as the mechanics of the

firearms. They had so much patience. I still remember that first day and how I used to feel nervous and insecure. Now, two years later, it's been replaced with focus, calmness and ease.

In the fall of 2022, my oldest son, Joseph, harvested his first big game animal. GSA gave me the confidence to mentor him in the field. As we walked through the forest, we covered safety over and over. What makes a good shot? What is ethical? We had practiced at the GSA rifle range, and he sighted in his own gun there. One day, during second season, everything came together for him. He made a good, solid shot and harvested his first cow elk.

That same season I had a tag that was burning in my pocket. With only one day left in the season, I gathered up my son's 6.5 Creedmoor, the rifle he had used to harvest his elk. I headed for the hills early in the

morning. I went to a location that we had scouted awhile back, hoping they were still in there.

Sure enough, thirty yards into dark timber, I jumped one. He took off. I tried to track him but realized after a great deal of walking that I wasn't ever going to catch up. I turned around. Snow had started to fall. I was tired and not far from my vehicle. As I sat down for a rest, movement caught my eye — a buck, right in front of me. This was the moment where all the skills I had learned came together. I felt calm, which came from all those Friday nights of shooting at GSA.

I made the shot and down he went. I, too, had harvested my first big game animal and had done it solo. d

(Nicole Schultheis finds passion and joy being in the mountains, fly fishing and doing fiber art.)

The Gunnison Country was known for its excellent hunting and fishing opportunities long before the first pioneer settlers arrived, as the native Ute people would spend the summer months hunting and gathering food in the area, departing before winter arrived. Following the removal of the Utes by the Los Pinos Indian Agency in the late 1800s, those arriving to settle this land found the area teeming with wildlife, and soon the extensive recreational opportunities of this region were no longer a secret.

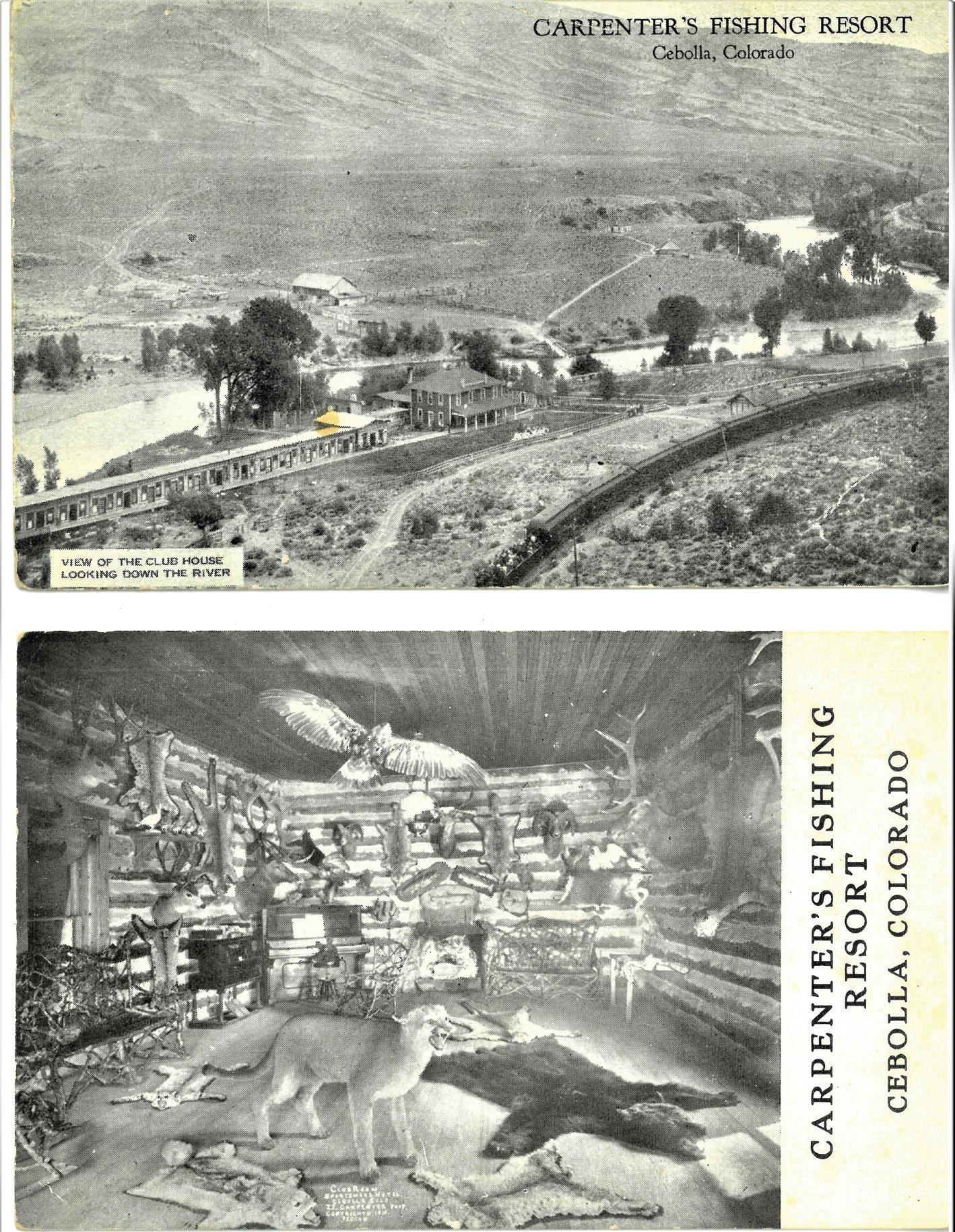

It was Jacob Jayhue Carpenter who founded the most renowned resort in the Gunnison Country, arriving from the Blue Ridge mountain region of North Carolina in the early 1880s. It was there that he had begun hunting bear at the age of 15 and where he taught his sons the trade. J.J. origi -

nally homesteaded and began ranching near Sapinero, but following a very successful fishing jaunt near the confluence of the Gunnison River and Cebolla Creek (pronounced “Sevoia”), he decided to give up on ranching and instead run a hunting and fishing lodge.

On April 20, 1882, the “Sportsmen’s Home” opened for business with 20 rooms in a frame building which would come to be known over the years as the Sportsman’s Lodge, Sportsmen’s Hotel and Carpenter’s Fishing Lodge. It was there that J.J. and his wife Louisa raised seven children, six boys and a girl — who would all become accomplished hunting and fishing guides, with big game hunting as their specialty.

J.J. marketed his resort to big game hunters across the country, with his sons guiding parties into the nearby hills to hunt deer, elk, mountain lion, mountain sheep and bear. But it was a young, orphaned bear cub named

“Nellie” — rescued by Jacob — that brought the resort nationwide fame. Nellie performed for guests by crawling up a small post, where she would be rewarded with a bottle of Neps, her favorite beer.

When Nellie died, a headline in the February 3, 1913 edition of the Montrose Daily Press reported, “Pet Bear at Cebolla Dead; Entire Town Present at Funeral.” The article stated, “The town of Cebolla gave Nellie a funeral that attained the proportions of a unanimous display of public grief. A handsome stone monument will mark the bear’s grave.”

During the winter of 1902, the original building burned to the ground, but it wasn’t long before a new one opened that offered a twostory “colonial style” lodge, enlarged dining room and 20 small log cabins, “as comfortable, clean and as well-kept as the rooms in the Brown Palace.” Another cabin was equipped

continued on 36

with games and music and “decorated with one of the largest and best collections of Colorado heads and skins ever collected by one man in Colorado.” The specimens included black bear, mountain lion, wild cat, elk, deer and hundreds of others.

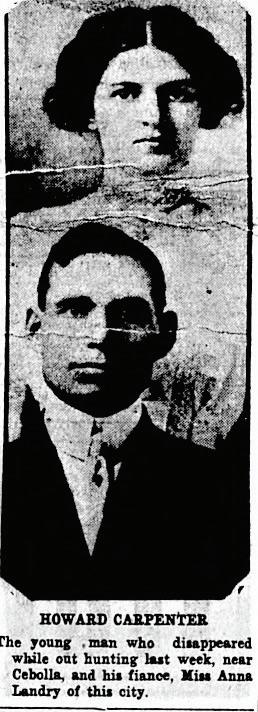

Tragedy struck the Carpenter family in 1912 when Howard, guiding a small hunting party up Steuben Creek, never returned. He had been engaged to be married the following week and his broken-hearted family never gave up the search until his remains were finally found nine years later. They had always suspected he was murdered, and a subsequent investigation determined Howard Carpenter came to his death by a gunshot wound that entered at

the base of his head and came out of his forehead; that said wound was inflicted by some person unknown to this jury. As to whether the wound was inflicted feloniously or not, we are unable to determine.” Although a number of theories emerged, the mystery remains unsolved to this day.

The Carpenters began selling off parts of the resort in 1929 but continued their involvement for another two decades. The popularity of the Sportsman’s Lodge continued well into the 1930s, with President Herbert Hoover spending a week there in 1939. After taking a canoe trip down the river, he said it was one of the highlights of his life, and that the beautiful mountain river was the

second-most magnificent he had ever seen.

In 1948, the Moncrief family from Texas purchased the resort, remodeling the old lodge, constructing numerous new buildings and renaming it the Moncrief River Ranch. Famous guests of the Moncrief’s included President Eisenhower, Bing Crosby, Doris Day, Bob Hope, Marilyn Monroe, Randolph Scott, John Wayne and many others.

In the early 1960s, the Bureau of Reclamation purchased the property to be used as the headquar-

ters for the construction of the Blue Mesa Dam and Reservoir. Soon, the entire valley was submerged under the lake. Prior to the completion of the dam, many of the buildings located in that beautiful valley were moved and used elsewhere, including the Sportsman’s Lodge. It was cut in half and relocated just north of Gunnison, where the intriguing legacy of the Carpenter family lives on today as the Cebolla Creek Apartments.

“After taking a canoe trip down the river, [President Hoover] said it was one of the highlights of his life, and that the beautiful mountain river was the second-most magnificent he had ever seen.“

Elk backstrap marinade:

8 tsp. olive oil

12 Tbsp. Dale’s marinade

Pinch of black pepper

Chimichurri:

1/4 cup olive oil

1/4 cup white wine vinegar

1 finely-minced clove of garlic

1 small shallot brunoise

1 tsp. crushed red pepper

1 tsp. black pepper

1/4 cup finely-chopped cilantro

1/4 cup finely-chopped parsley

Summer salad:

2 ears Olathe sweet corn, removed from cob

2-3 vine-ripe tomatoes, sliced

2 large summer squash, sliced

1 lb. shitake mushrooms, sliced

Summer salad dressing:

Juice of 1 lemon

1/4 cup olive oil

Salt and pepper to taste

Preheat the oven to 425 degrees Fahrenheit. Prepare marinade and then soak 32 oz. of elk backstrap while prepping summer salad vegetables. Toss sliced shiitake mushrooms and summer squash in 1-2 Tbsp. olive oil with salt and pepper to taste. Arrange mushrooms and squash on a baking sheet, then roast on the top rack of the oven for 10-12 minutes. Check frequently and remove when crispy.

While the vegetables are roasting, combine Chimichurri ingredients in a medium bowl and set aside. In a small bowl, combine summer salad dressing ingredients and set aside. Cook the marinated elk backstrap over medium-high heat for 2.5 min on each side. Let rest for 3 minutes, then slice against the grain. Top elk medallions with Chimichurri. Add roasted vegetables to a large bowl with cobbed sweet corn and tomatoes. Toss with summer salad dressing and serve.

let, cook the bacon over medium heat until crisp and the bottom of the pan is coated with the rendered fat, 5-8 minutes. Transfer the bacon to paper towels to drain, then cut into small pieces. Put the skillet over high heat. When the fat is hot, gently put the salmon in the pan, pinker-side down. (One side of a salmon filet will be bright pink and the other side will have a strip of dark flesh running down the center. The bright pink side is the one you want to brown.) Sear until nicely browned on the bottom, about 3 minutes.

Using two large spatulas, carefully transfer the salmon to a sheet of heavy-duty aluminum foil, brownedside up. Add the onion to the fat in the pan and sauté over medium-high heat until translucent, about 2 minutes. Add the garlic and the remaining spice blend and stir until aromatic, about 20 seconds. Stir in the lentils, broth and tomatoes with their juice and simmer for 10 minutes.

From “Cooking Slow: Recipes for Slowing Down and Cooking More” (Chronicle Books) by Andrew Schloss

1 1⁄2 lbs. wild-caught salmon filet in 1 large piece about 1 1⁄2 inches thick, skin removed

2 bacon strips

1 medium yellow onion, finely chopped

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 cup red lentils

1⁄2 cup canned diced tomatoes, with juice

2 cups quality low-sodium chicken or vegetable broth

2 Tbsp. fresh cilantro, chopped

Spice rub:

2 tsp. ground coriander

1 tsp. ground cumin

1 tsp. ground turmeric

1⁄2 tsp. sweet paprika

1⁄4 tsp. ground cinnamon

1⁄8 tsp. cayenne pepper

1 tsp. coarse sea salt

1⁄2 tsp. freshly-ground black pepper

To make the spice rub: in a bowl, mix together all ingredients. Rub 2 teaspoons of the mixture into the flesh of the salmon filet and set aside for 30 minutes.

Preheat the oven to 200 degrees Fahrenheit. In a large cast-iron skil-

Using the foil as a kind of large spatula, carefully slide the salmon onto the lentils. Cover the skillet with a lid or a clean sheet of heavy foil and bake until the thickest part of the fish flakes to gentle pressure and the lentils are tender, about 1 hour. Garnish with chopped cilantro and slip onto a large platter or serve directly from the pan.

From “Texas Favorites” (Gibbs Smith) by Jon Bonnell.

2 lbs. venison

1⁄2 lb. pork shoulder

1⁄2 lb. slab bacon

1 Tbsp. Worcestershire sauce

1⁄2 tsp. onion powder

Pinch of cayenne pepper

1⁄2 tsp. garlic powder

2 Tbsp. Dijon mustard

2 tsp. hot sauce

1 tsp. kosher salt

1⁄2 tsp. freshly ground black pepper

Clean the venison well and remove any fat or connective tissue. Cut the venison, pork shoulder and bacon into large chunks, or dice into small chunks if you are working without a meat grinder. Combine all ingredients together in a large mixing bowl

and let marinate for 1 hour in the refrigerator. Grind everything together using the small plate on your grinder, if available. Form into burger patties by hand and grill or pan-sear. Cook to medium, making sure the meat reaches an internal temperature of 135 degrees Fahrenheit, then remove from the grill and top with your favorite burger toppings.

(Courtesy Metro Creative)

(Courtesy Metro Creative)

COMMERCIAL GRADE PROFESSIONALLY CLEANED

Joseph Kean: (605) 280-8333 or Homesteadhut@gmail.com

Homesteadhut.com

(Courtesy Metro Creative)

(Courtesy Metro Creative)

COMMERCIAL GRADE PROFESSIONALLY CLEANED

Joseph Kean: (605) 280-8333 or Homesteadhut@gmail.com

Homesteadhut.com