Architecture. Landscape architecture. Interior design. Our professionals work side-by-side to create fully integrated, client-centered design solutions that transform each project vision into reality.

Tracy Barbour

Alexandra Kay

First National understands the unique challenges of doing business in Alaska. Facing tight deadlines and remote locations, you need a bank that moves as quickly as you do — one that is responsive, reliable, and able to make decisions locally. Let’s work together to build Alaska’s future, one project at a time.

Explore how Drake Construction and First National Bank Alaska work together to build Alaska one community at a time.

40 OUTSIDE SPEAKS TO INSIDE

Beneath the surface of interior design

By Scott Rhode

46 BIG SOLUTIONS IN SMALL PACKAGES

How Petersburg is tackling its housing shortage

By Katie Pesznecker

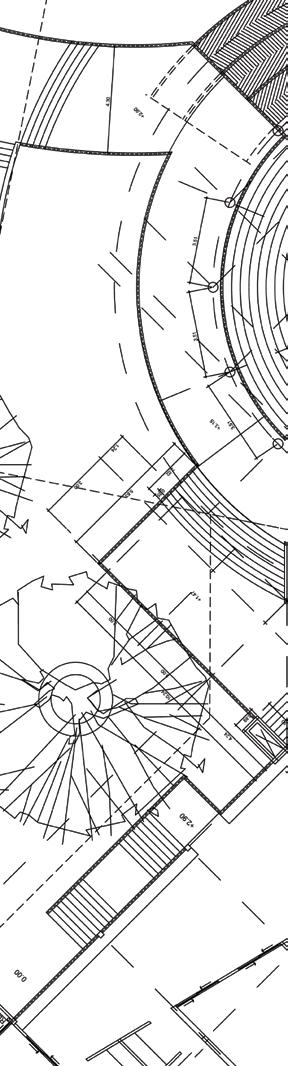

76 BLUEPRINTS FOR THE GOLDEN HEART

Multidisciplinary firm Design Alaska

By Vanessa Orr

52 MAKE IT RAIN

Fire prevention and protection for building safety

By Rachael Kvapil

56 3D PRINTED HOMES

Automated construction with advanced materials

By Vanessa Orr

66 SPARKING IDEAS, DELEGATING DETAILS

AI is proving useful for small businesses

By Rindi White

72 WINNING THE WORK

Meet the Society for Marketing Professional Services

By Amy Newman

60 2024 ANCHORAGE ENGINEER OF THE YEAR NOMINEES

Look up at Loussac Library and notice the texture of the ceiling in the bridge connecting its fortress-like turrets. Loussac Library, designed by Environmental Concerns, Inc. of Spokane, Washington, is the second building to carry the name of that former Anchorage mayor. The first, funded by Z.J. Loussac’s philanthropic efforts, was built in the ‘50s in a prime position in Downtown Anchorage along Fifth Avenue.

In the ‘70s, the city grew (and merged with its surrounding borough), and another mayor pushed for public investments worthy of the burgeoning metropolis. George M. Sullivan was the driving force behind Project 80s, a slate of state-funded construction projects. Those buildings included the new Loussac Library, the Egan Civic & Convention Center on the site of the previous library, the Alaska Center for the Performing Arts across the street, and the multipurpose arena named in Sullivan’s honor.

On the occasion of this magazine’s 40th anniversary, this month’s article “Anchorage’s Aspirations” checks in with those physical manifestations of that decade’s civic spirit.

Cover by Monica Sterchi-Lowman

So me years ago, my father and I watched The Red Green Show perform at the Alaska Center for the Performing Arts (PAC). It was a delightful show, largely because my father and I both enjoy Red Green’s humor, but I also remember how the audience members themselves added to the evening’s atmosphere. Dad and I noticed, as we sat in the auditorium waiting for the production to begin, that there were two types of attendees. About half of the audience wore a combination of flannel shirts and jeans; the other half sported suits and evening gowns. Did someone miss the memo on the dress code?

Absolutely not. One of the great joys of the PAC is its function as a community hub, and in Alaska, that community includes those who dress for comfort and those who are looking for an excuse to wear elbow-length gloves. I remember attendees chatting politely before the show began, no one paying much attention if their partner in conversation was sporting a tie or work boots.

Growing up in an Anchorage that boasted such a community venue, I didn’t give much thought to whether or not my hometown’s population justified a performing arts space with multiple auditoriums. As an adult, I’m grateful that forty years ago the Anchorage community, awash with funds derived from North Slope oil and gas production, chose to invest in the city and its future. In an interview for this issue’s cover story, Codie Costello, president and chief operating officer for the PAC, said, “We’d be a very different place without these community venues… I think it’s important to acknowledge that gift. I think it’s important for us to reimagine how we invest in and maintain those gifts.”

The spaces in which we spend time influence us long after we’ve left them. Designing community buildings and spaces to be safe, functional, comfortable, and welcoming isn’t a nicety, it’s a necessity. Alaska’s architects and engineers excel at crafting places that can be filled with art, music, conventions, and commerce, creating moments that turn Anchorage residents into neighbors and friends. Such venues gather Alaskans in denim and flannel with those in silk and beads to learn, grow, and laugh.

Tasha Anderson Managing Editor, Alaska Business

EDITORIAL

Managing Editor

Tasha Anderson 907-257-2907

tanderson@akbizmag.com

Editor/Staff Writer

Scott Rhode srhode@akbizmag.com

Associate Editor

Rindi White rindi@akbizmag.com

Editorial Assistant

Emily Olsen emily@akbizmag.com

Art Director

Monica Sterchi-Lowman

907-257-2916

design@akbizmag.com

Design & Art Production

Fulvia Caldei Lowe production@akbizmag.com

Web Manager

Patricia Morales patricia@akbizmag.com

VP Sales & Marketing

Charles Bell 907-257-2909

cbell@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager

Janis J. Plume 907-257-2917

janis@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager

Christine Merki 907-257-2911

cmerki@akbizmag.com

Marketing Assistant

Tiffany Whited 907-257-2910

tiffany@akbizmag.com

President

Billie Martin

VP & General Manager

Jason Martin

907-257-2905

jason@akbizmag.com

Accounting Manager

James Barnhill 907-257-2901

accounts@akbizmag.com

Press releases: press@akbizmag.com

Postmaster: Send address changes to Alaska Business 501 W. Northern Lights Blvd. #100 Anchorage, AK 99503

By Tracy Barbour

Co mmunity development

financial institutions (CDFIs) share a distinct mission: to expand economic opportunities in communities traditionally overlooked by banking and investing services. There are approximately 1,000 certified CDFIs in the United States, and 8 of them operate in Alaska.

The CDFIs in Alaska are Alaska Growth Capital (AGC), Alaska Benteh Capital, Cook Inlet Lending Center (CILC), Haa Yaḵaawu Financial Corporation, NeighborWorks Alaska, HomeOwnership Center, Spruce Root, and Tongass Federal Credit Union (TFCU). These mission-driven, private-sector entities often work together to serve low- and middleincome individuals in urban and rural areas. They promote selfsufficiency, economic growth, and community redevelopment.

Meet the Institutions

TFCU—Alaska’s only depository CDFI—focuses on improving the lives of individuals and organizations

throughout Southeast by offering innovative financial services and education. “By supporting small businesses and nonprofits through loans, technical assistance, and partnerships—like our work with Native CDFI Spruce Root—we help foster economic growth,” says President and CEO Helen Mickel.

“Financial literacy is also a key focus, as we equip our members with the knowledge to make informed financial decisions.”

With its “people-helping-people” philosophy, TFCU works to be a part of each community it serves.

the resources they need to thrive,” Mickel says.

At CILC, the primary goals are to improve the financial knowledge and wellness of its communities; expand its outreach, products, and services to serve more people; and diversify its funding sources for greater sustainability and opportunities.

“As a Native CDFI, CILC vigorously pursues opportunities to financially empower Alaska Native families, businesses, and communities,” says President and CEO Jeff Tickle.

“We wear that CDFI banner with commitment to community development in any way we can support and build on it. Our CDFI certification allows us to cultivate communities where everyone has access to opportunity, respect, and

CILC offers a variety of financial products and services to underserved populations, including down payment assistance loans, primary mortgage loans, and down payment assistance grants (Home$tart and Native American Homeowner Initiative) as a member of Federal Home Loan Bank of Des Moines. It also provides micro and small business loans and credit lines, as well as financial wellness services. For 2025, CILC plans to launch a credit builder loan product.

AGC is also a Native CDFI, founded by Arctic Slope Regional Corporation in 1997 as the state’s first Business and Industrial Development Corporation. McKinley Management acquired AGC in 2022 with Bristol Bay Native Corporation. As of 2025, McKinley became the minority partner while Bristol Bay Native Corporation took majority control.

generations. “We are a driver of a regenerative economy across Southeast Alaska, so communities can forge futures grounded in this uniquely Indigenous place,” says Executive Director Alana Peterson.

AGC’s niche and expertise is lending in rural areas and to Native-owned businesses. “Our goal is really to help get our clients to a ‘yes’ on their loan when they have not been able to successfully access financing elsewhere,” says Mary Miner, vice president of community development.

AGC primarily provides Small Business Administration 7(a), US Department of Agriculture, and Business and Industry Guaranteed loans. With its average loan being about $1 million, AGC lends in the range of $250,000 to $10 million. “Our structure and utilizing government guarantees allows us to be more flexible than other lenders,” Miner says.

AGC, whose portfolio is just under $100 million, has a loan volume of $17 million to $25 million annually. It provides financing for diverse industries, ranging from transportation to hospitality to tourism. AGC also offers technical training and community education.

Spruce Root has a unique vision: to amplify its Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian ancestral imperative to ensure Southeast thrives for future

Spruce Root offers Fast Start Loans—zero-collateral financing up to $50,000 for qualifying borrowers— and standard business loans up to $500,000. Since its inception in 2012, it has deployed more than $4 million in lending capital to establish small businesses in Alaska. “In 2023 alone, ten loans totaling $850,000 were deployed across seven Southeast Alaska communities,” Peterson says.

Although the term “CDFI” is relatively new, the concept extends back to the 1930s with AfricanAmerican communities forming

the first credit unions and even earlier to the 1800s with immigrant guilds in New York City’s Lower East Side. In 1994, Congress extended CDFIs nationwide when the Riegle Community Development and Regulatory Improvement Act establ ished the CDFI Fund.

Managed by the US Treasury Department, the CDFI Fund offers certification to CDFIs, which allows them to apply for financial and technical assistance awards. For example, grant funds enabled TFCU to establish local services in remote villages through co mmunity microsites.

“The funds have also allowed us to provide affordable lending to low- to moderate-income borrowers with less-thanperfect credit,” Mickel says. “Our financial education initiatives have also been supported throug h funding received.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal funding had a significant impact on CILC. It was able to partner with the Municipality of Anchorage to administer grants to small businesses, nonprofits, and artists totaling mo re than $30 million.

The CDFI Fund also has the New Markets Tax Credits Program. Begun in 2002, it encourages privatesector investment by offering tax credits for qualified community development investments. In Alaska, AGC is the only entity that receives those credits, according to Miner.

The Native Initiatives CDFI Program provides further capital. “The CDFI fund is our largest supporter, and we are grateful for all the resources that it provides,” Miner says.

There are six basic types of CDFIs: community development

“All

of our loan officers here came from the conventional banks in

deep

Alaska, so they have

connections with those lenders… It takes a village to help move some of these big initiatives forward and to help small businesses.”

Mary Miner, Vice President of Community Development, A laska Growth Capital

• Bill Pay to automate regular payments

• Merchant Services to accept debit or credit cards

• Positive Pay to help prevent check fraud

• Business Remote Deposit to save you time

Call 877-646-6670 or visit globalcu.org/business to talk to a specialist today!

The

banks, community development loan funds, community development credit unions, microenterprise funds, community development corporation-based lenders and investors, and community development venture funds. CDFIs do not replace conventional financial institutions; th ey complement them.

Partnerships are vital to the success of CDFIs. “For example, the Kake Tribal Corporation and the Hoonah Indian Association have provided space for our community microsites, allowing us to bring essential financial services to remote areas,” Mickel explains. “We also partner with schools and community organizations to deliver financial literacy programs, ensuring that individuals and families have

the knowledge to make sound financial decisions.”

Spruce Root has partnered with local banks to spread the word that a “no” on traditional financing does not have to mean the end of a small business owner's journey to financing. Peterson adds, “We have worked very hard to build relationships with municipalities, tribes, nonprofits, and other nontraditional lenders to find the entrepreneurs that are seeking support and to make sure that we are giving them the option that is best for their business—whether or not t hat is Spruce Root.”

have a very strategic partnership with the Anchorage Community Land Trust (ACLT) and Cook Inlet Tribal Council around ACLT’s initiative of an Indigenous Peoples Set Up Shop program, in which ACLT provides business training and assistance and CILC provides lending services and capital,” Tickle says. “This partnership with ACLT is a primary reason Cook Inlet Lending now has a Small Busine ss Lending program.”

CILC is part of a small business scaffold in the Anchorage area. “We

CILC is also part of a Native CDFI and Friends cohort that shares best practices, challenges and opportunities, and regular updates. It has also engaged in a home lending cohort with Coloradobased Oweesta Corporation and other Native CDFI’s. They have provided CILC with insights into various mortgage financing opportunities, along with

Cook Inlet Lending Center's headquarters is in Anchorage's Spenard neighborhood, across the street from Cook Inlet Housing Authority. The social enterprise of Cook Inlet Region Incorporated launched CILC in 2001 to address development services in addition to home financing.

Cook Inlet Lending Center

“We have worked very hard to build relationships with municipalities, tribes, nonprofits, and other nontraditional lenders to find the entrepreneurs that are seeking support and to make sure that we are giving them the option that is best for their business.”

Alana Peterson Executive Director Spruce Root

technical assistance from the Homeownership Council of America.

AGC is somewhat positioned in the middle between CDFI partners and conventional lenders. For instance, AGC relies on Spruce Root’s award-winning, nationally recognized Path to Prosperity curriculum for its regional Marketplace business plan competitions. Spruce Root serves as AGC’s lead facilitator of training. On the lending side, AGC exchanges referrals with Spruce Root and CILC. Miner explains, “Our teams are regularly meeting and figuring out how we can suppor t small businesses.”

AGC also collaborates with traditional lenders. “All of our loan officers here came from the conventional banks in Alaska, so they have deep connections with those lenders and are regularly meeting with them,” Miner says. “It takes a village to help move some of these big initiatives forward and to hel p small businesses.”

CDFIs often measure success by focusing on the “double bottom line” of economic gains and the contributions they make to the local community, according to the CDFI Coalition. CILC, for instance, measures the number of families or individuals who secure affordable stable housing through its homeownership programs as well as the number of businesses started or expanded due to its financing. CILC also assesses the businesses’ demographics and impact within the community. “We use a ‘mission matrix’ within our small business loan program,” Tickle says. “We track the number

of jobs created or retained through our small busine ss lending as well.”

CILC also plans to measure participation in financial education workshops and its soon-to-belaunched credit builder loan program. It will evaluate how its people are improving their financial literacy and long-term financial health through changes in credit scores, savings, and debt levels being tracked over time.

“We aim to collect client feedback and success stories to help us assess the broader, less tangible benefits of our ser vices,” Tickle says.

A recent funding success story of CILC is Yukon Tails, a mobile pet grooming business in Wasilla. Its owner, Teela Bieschke, identified the need for mobile pet grooming when she was unable to find services for her elderly dog experiencing mobility challenges. After being placed on lengthy waiting lists, she decided to start Yukon Tails. “Cook Inlet Lending Center was thrilled to partner with Teela and Yukon Tails to help launch this exciting new business ve nture,” Tickle says.

Spruce Root helped long-time client Edith Johnson launch Our Town Catering in Sitka. According to Peterson, Johnson’s journey included Spruce Root from the beginning when she received assistance to establish her LLC. From there, she participated in Spruce Root's training programs to start her first small business and worked on her personal finances to purchase her first home. By then, she was ready to approach Spruce Root for a loan to purchase her second business. “Her journey exemplifies our missions to

empower local talent and support local businesses,” Peterson says. “We feel so fortunate to be witness to the positive impact people like Edith have on our region's community, cu lture, and economy.”

One of TFCU’s proudest success stories is its work with the Metlakatla Indian Community. When the only bank branch on the isolated island closed in 2005, residents were left without access to essential financial services. TFCU stepped in by offering weekly services and, within a few months, opened a branch in the old bank building. “Over the years, we’ve introduced a range of services from home equity loans to financial education in local schools,” Mickel says. “Today, 85 percent of the community are Tongass FCU members, and the median credit score has risen by seventy-four points, reflecting the positive impa ct of our services.”

TFCU is committed to continuing its efforts to strengthen the economic resilience of Southeast, Mickel says. The credit union recently hired additional staff to support the growing team at its main office in Ketchikan, which oversees all its other locations. It’s also planning to build a larger office in Ketchikan to accommodate this expansion. Additionally, TFCU is expanding its financial education programs and introducing new financial products like Lifestyle Loans to meet the evolving needs of its members. Mickel says, “These initiatives, along with continued partnerships with local organizations, will help us provide the financial tools and resources that our communities need to thrive.”

By Scott Rhode

Pi zza toppings. Jay Leno reportedly compared the crazy-quilt pattern of the Atwood Concert Hall’s freshly installed carpet to Italian food in 1988 when he performed the venue’s inaugural show. Four decades later, the carpet is still there, a little worse for wear but holding up respectably.

The Atwood is the largest and most elegant of the three auditoriums in the Alaska Center for the Performing Arts (PAC). The city-owned structure is open to the public only a few hours per day, a few days per week, which cuts down on carpetscuffing foot traffic.

“My team does an amazing job of taking care of this facility that we are so fortunate to have,” says Codie Costello, president and chief operating officer of Alaska Center for the Performing Arts, the nonprofit organization contracted by the Municipality of Anchorage to manage the PAC.

Carpeting inside the Egan Civic & Convention Center, across Fifth Avenue from the PAC, was replaced a few years ago, but some forty-year-old fixtures are still there. “The ficus trees that were original to the building were seven feet tall; they now fill up the space,” notes Steve Rader, general

manager of Anchorage Convention Centers, the local branch of facility management firm ASM Global.

The Egan and the PAC are more than neighbors. They are manifestations of Alaska’s oil boom. Forty years ago, cashflow from the North Slope enabled the state treasury to bankroll public buildings in Anchorage. In addition to the PAC and Egan, the cohort included the Sullivan Arena, the new Loussac Library, a two- story atrium for the Anchorage Museum, and the Downtown Transit Center. Together, they were known as Project 80s. They were all built around the same time as Alaska's tallest skyscrapers, the ARCO Tower (now the ConocoPhillips Building) and the Hunt (now Atwood) Building.

The buildings have undergone some changes through the decades, and more facelifts are due as the Project 80s structures inevitably age.

The immensity of the PAC caught Costello’s attention in 2005 during a honeymoon visit. “We walked by this building and couldn’t believe that a community of this size had an asset like this,” she recalls. When a job opened up at the PAC, she jumped at the opportunity to move to Alaska.

“I can’t imagine Downtown Anchorage without the PAC,” she says.

Before the PAC, the block between Fifth and Sixth Avenues was known as Anchorage’s “skid row,” packed with bars and adult entertainment. In 1979, the firms of Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates of New York and Livingston Slone, Inc. drew plans for a civic auditorium. Critics immediately wondered if it was too large, too ostentatious for the city.

The $71 million building stretched into F Street, and the right-of-way has been blocked ever since. The Anchorage Assembly voted 10 to 1 to name the PAC in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr., but a political backlash left the building without a proper name to this day. (King eventually got an Anchorage tribute with a road dedicated in 2010.)

Political activism also led to the creation of Town Square Park adjacent to the PAC. The block across Fifth Avenue had been reserved for future parkland, so a citizens committee insisted that Project 80s not interfere with that designation. When half of the block became the Egan Center in 1984, the town square development was part of the bargain.

“We’d be a very different place without these community venues… I think it’s important to acknowledge that gift. I think it’s important for us to reimagine how we invest in and maintain those gifts.”

Codie Costello President and Chi ef Operating Officer Alaska Center for the Performing Arts

Named for Alaska’s first state governor, William A. Egan, the $31 million center satisfied the city’s need for a facility to host larger meetings. Anchorage architect Edwin B. Crittenden designed a 45,000-square-foot building with some unique features. Elevated booths in the ground-floor Explorers Hall allow language interpreters to assist with international gatherings. Also, the ficus trees in the lobby required a special floor to irrigate their roots.

To make way for the Egan, the city demolished the original Loussac Library, built in 1952 and named for Zack Loussac, who ran Anchorage’s first drugstore and served a

term as mayor. His philanthropic foundation had funded the downtown library on the same block as Anchorage’s historic city hall.

Many of those city hall functions shifted to Midtown, where the Anchorage Assembly chambers were incorporated into the new Loussac Library. The castle-like edifice, with three cylinders linked by a massive bunker, opened in 1986.

Cylinders are a common motif at the four corners of the Sullivan Arena, completed in 1983 at a cost of $25 million. Part of the Chester Creek Sports Complex along with the nearby baseball and football fields and indoor and outdoor ice sheets, the arena is named after George M. Sullivan. The first mayor of the unified Municipality of Anchorage got the ball rolling on Project 80s buildings, while his successor, Tony Knowles, presided over ribbon cuttings later in the decade.

The Sully, as the arena is known, has seen busier days, hosting concerts, trade shows, and graduation ceremonies. It was the home of the Alaska Aces professional hockey team until that organization folded in 2017. UAA played hockey there until 2019. The arena hosted the Great Alaska Shootout college basketball tournament each Thanksgiving from 1983 to 2013. The following year, the university opened the Alaska Airlines Center, and the on-campus arena has cut into the Sully’s turf.

Last summer, the Anchorage Wolverines of the North American Hockey League relocated home games from the 700-seat Ben Boeke to the 6,200-seat Sully. After the season wraps up in April, the arena

is scheduled to host comedian Tom Segura. Rock band Five Finger Death Punch is booked to play the arena in August.

Not that it’s a contest, but the Anchorage Public Library system boasts of serving more visitors than the Sully. Nearly a million annual visits are spread among four other branch libraries while the headquarters at Loussac oversees circulation of more than 1.7 million books, media, and digital materials each year. Like the Anchorage Museum expansion and the Downtown Transit Center, it’s a Project 80s building that sees traffic nearly every day of the year.

The Egan has remained busy even though the Dena’ina Civic and Convention Center grabbed its crown as Anchorage’s premier meeting venue in 2008. ASM Global manages both buildings under a contract through Visit Anchorage, the nonprofit tourism bureau.

“If you live here and you’re maybe not Downtown as frequently, it’s really easy to not see the impact here. We have thousands of guests that are going through here on a daily basis,” says Rader of the Egan. “There’s a ton of activity; this is not an empty building.”

On the day of the interview, for example, while the US Bureau of Indian Affairs was meeting at the Dena’ina, the Egan’s downstairs conference rooms hosted the North Pacific Fisheries Management Council, and a boxing ring upstairs was set up for Thursday Night at the Fights.

“I think there’s a lot more going on in Anchorage—when it comes to meetings and conventions and being a cruise hub—than a lot of people realize,” Rader says. “All summer long, this is really a cruise hub for Anchorage.”

“Everything has their lifespan, so you reach the point where it makes more sense to go through the full modernization.”

Steve Rader General Manager

Anchorag e Convention Centers

Not having a waterfront cruise ship terminal, Anchorage adapted the Egan to that purpose. Holland America-Princess, Royal Caribbean, and Premier Alaska Tours use the curb frontage on Fifth Avenue to load motorcoaches and process luggage. Passengers can wait in the conversation pits in the expansive lobby. The building has evolved into Anchorage’s front parlor.

In addition to managing the Egan and Dena’ina, ASM Global used to manage the Sully. But that was before the global pandemic.

Five years ago, the Sully provided space for Anchorage’s homeless population to congregate at a safe distance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Stepping up as a shelter resulted in damage that Project 80s builders never anticipated, and entertainment functions were interrupted for three years.

Upon reopening in 2023, the Sully was under new management. Instead of Anchorage Convention Centers, the city tapped O’Malley Ice and Sports Center to operate the arena. Steve Agni and the late Sig Jokiel founded the organization in 1999, and it has grown into the largest sports facility operator in Alaska, owning and/or managing the O’Malley Sports Center, Kelly Connect Center, Dempsey Anderson Ice Arena, and the Ben Boeke Ice Arena.

The contract lets O’Malley collect 50 percent of the profits after deducting operating costs, while the city remains responsible for upkeep of the Sully, Ben Boeke, and Dempsey Anderson arenas.

The management situation is different at the PAC. The city pays Costello’s organization a flat fee, which covers about 20 to 25 percent of operating costs. Ticket sales and fundraising fill the rest of the budget.

“We’re pretty scrappy, and we make a lot happen with very little. However, after thirty-six years and limited investment, the building is in need of modernization,” Costello says. The punch list includes everything: plumbing, HVAC, theatrical lighting and sound, seats, and compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

“We were built right before the ADA became law, so there are a number of things in this facility that weren’t addressed at the time of construction,” Costello says.

Indeed, the PAC was rushed to completion. Costello observes, “Our administrative offices, we sandwiched them in under the Atwood Concert Hall. But there was supposed to be a shared services and

administrative building (that included a rehearsal studio and offices), but that never came to be.”

From the moment of its completion, the PAC suffered from a leaky roof. A 2005 revenue bond funded a fix. While the roof has been repaired, Costello notes that the bond is still ten years away from being paid down.

Another minor alteration occurred in 2009 when aisles in the Atwood were widened by a few inches so that masked performers in The Lion King could safely step through the house. That modification will pay off again when the show returns to the PAC next season.

Loussac Library was likewise born defective. The original design called for a parking garage with a secondfloor entrance, but the economic decline of the mid-‘80s forced a change. The garage was scrapped, and library visitors had to brave a massive outdoor stairway, which was notorious for ice buildup until it was renovated in 2018.

The Sully received a $9 million renovation in 2015, including new seats, improved acoustics, and a video scoreboard as a handme-down from the Cow Palace south of San Francisco.

One upgrade at the Egan that wasn’t feasible in the ‘80s is the addition of rooftop solar panels. The building now has 212 panels supplementing its power supply. Rader says the energy savings over eight years is expected to exceed installation costs, totaling $700,000 in savings over the lifetime of the hardware.

“We’ve made some really great improvements in the last five years,” Rader says.

About twenty years ago, one of the most visible alterations was a skybridge over Fifth Avenue connecting the Egan and the PAC. The structure might seem frivolous, but Jennifer Ramsey, director of sales and marketing for Anchorage Convention Centers, says it has been useful. Performers at the PAC sometimes use the passage to make appearances at Egan events. And

Ramsey says she recently fielded an inquiry about the skybridge hosting a twenty-person dinner overlooking the bustling avenue.

Keeping the Project 80s buildings as shiny as when they were new takes constant maintenance. At the Egan, for instance, Rader says, “We’re doing a barrel glazing project to repair the

Tired of tiny hotel rooms?

Enjoy a full kitchen, separate bedroom, and a cozy living area at Sophie Station Suites - it’s like having your own apartment on the road! Book direct for the best rates, no hidden fees and flexible corporate options.

Looking west along Fifth Avenue circa 1983, when the Egan Center was under contruction, the left side of the image shows no sign of Town Square Park or the Alaska Center for the Performing Arts, which were both a few years from being built.

Ken Graham Photography

west entrance and skybridge.” That project will refresh the distinctive curved glass roof that shelters summertime tourists.

The Egan and Loussac Library are also due for elevator upgrades.

“Everything has their lifespan, so you reach the point where it makes more sense to go through the full modernization. They upgrade the cables and everything along those lines,” Rader explains.

Consolidated Contracting & Engineering won the job for the elevator modernization, totaling more than $1 million between the Egan and Loussac. Meanwhile, Visser Construction has a $434,331 contract for repairs to the Sullivan Arena plaza this year.

At the PAC, modernization is part of the Project Anchorage proposal for public improvements funded by a municipal sales tax. Whether adopted or not, and whether the PAC remains in the list of capital projects, Costello says upgrades are overdue.

“We are behind in technology, everything from sound to lighting. There are modernizations that we made along the way, as we’re able to find funds, but those investments are

significant,” she says. For example, the house lights in the Atwood were partially converted to more efficient LED fixtures, but not all of them. And for stage lighting, LED instruments that can “throw” 100 feet or more are the state of the art, but they are expensive.

Now that the PAC is a co-producer, with the Nederlander Organization, of the Broadway Alaska series, the need for up-to-date stagecraft is more urgent. Costello says the first couple of seasons made do with the PAC’s old equipment.

“The Broadway shows are unique in that, because they tour to so many different kinds of venues, they bring a lot of their stuff. But that also increases costs,” she says. “We can’t say to them, ‘Don’t worry. You don’t have to bring that because we have it here for you.’”

In a way, the citywide investments proposed for Project Anchorage are an echo of Project 80s, driven by the same spirit of civic pride, but without the windfall of revenue.

During the oil boom of the ‘70s, the population of Anchorage surged

from less than 50,000 to nearly 200,000. Presiding over that era as mayor from 1967 to 1981, George M. Sullivan envisioned a municipality with public buildings worthy of a grander city. In the next decade, Sullivan saw the vision take shape in concrete, steel, and glass.

While many of Anchorage’s historic buildings are 100-year-old cottages from the original townsite or midcentury relics of post-war expansion, Project 80s planted functional landmarks that signaled the city’s aspirations to world-class status.

“It’s iconic,” says Rader of the Egan Center’s glass barrel façade. “I think it adds allure for Anchorage. Beautiful design.”

Yet the buildings are only as monumental as the users who fill them. Of the PAC, Costello says, “This building is such a gift, and we are lucky to have it. It’s the home to many dreams and transformational experiences for all of our community.”

The library, museum, performing arts center, and other public facilities benefit the whole community. Costello says, “It’s part of what makes a community a community. A way for us to gather, to connect, to grow.”

By Tasha Anderson

Re g Dog mine began operations in 1989 and currently has a projected mine life until 2031; however, in late November 2024, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) announced its decision to issue a permit that allows for the construction of a road to support Teck Resources Limited exploration activities that could further extend operations at the mine—and its contributions to local and statewide economies.

Red Dog operator Teck and landowner NANA regional corporation welcomed the permit approval. According to NANA Vice President of Natural Resources Lance Miller, “This was the last permit needed to construct the exploration road and advance the evaluation of the project. This milestone was reached after many, many hours of work by Kivalina, Teck, and NANA leadership.”

Those many hours were in fact spread over multiple years.

Teck holds mining claims near Red Dog on state land: the Aktigiruq and Anarraaq mineral deposits, approximately 9 miles north of the Red Dog Mine. According to Teck Manager of Community and Public Relations Wayne Hall, the company submitted its initial Section 404 permit application to USACE in May 2018 to advance the exploration phase of the Aktigiruq Project. “Teck

worked closely with local subsistence hunters, who walked potential road routes with engineers to incorporate traditional and local knowledge in identifying the best route to minimize impacts in advance of the permit submission,” Hall says.

Teck resubmitted its permit application, which included additional information, to USACE in February 2022.

According to Teck, “The required tribal consultation process

“Our overall goal is to extend the mine’s life and continue the significant social and economic benefits the mine contributes to local communities and the region.”

Wayne Hall, Manager of Community and Public Relations, Te ck Resources Limited

I am a safety expert. I am a volunteer. I am mining.

I grew up watching the Fort Knox mine being built. Now I’m their health and safety coordinator and raising my own kids in the community. Mining has allowed my family to stay in the Interior and given me the skills to volunteer on the Borough’s Hazmat Response Team to support our first responders and help keep people in our community safe.

“With more than 85 percent of the NAB [Northwest Arctic Borough] budget from Red Dog and over 980 shareholder jobs earning about $63 million in annual wages, any gap may have significant negative economic consequences for the region.”

Lance Miller Vice President of Natural Resources

administered by the USACE has taken longer and has been much more complex than we anticipated and resulted in multiple delays from the original environmental review process schedule.” Just recently, a decision deadline of September 30, 2024 was extended to October 31, 2024—the eighth such deadline extension.

By late 2024, the project had received eighteen other required permits from state and local government agencies, with only the Section 40 4 permit remaining.

The permit’s approval in late November set the ball rolling for an exploration project that is now on a tight deadline.

According to Hall, “This permit approval is an important step forward which allows start of construction of the 9-mile access road needed to evaluate the technical and economic feasibility of two deposits that could potentially extend Red Dog mine's life.” Road construction began as 2024 came to an end, and construction of the road is projected to take nine to twelve months over two winter seasons.

According to an April 2022 Plan of Operations for the Aktigiruq Project exploration program that Teck submitted to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, the company anticipates exploration activities would take place year-round for an estimated four years. If exploration progresses as expected and Teck delineates a technically and economically feasible deposit, the company could potentially extend Reg Dog mine’s life beyond 2031.

“Our overall goal is to extend the mine’s life and continue the significant social and economic benefits the mine contributes

to local communities and the region,” says Hall, adding that, even with the permit in place, “Time is of the essence to construct the exploration facilities and complete our evaluation o f mineral deposits.”

The April 2022 plan of operations noted that construction related to exploration activities would be divided into two phases, with Phase I seeking approval for “certain surface civil construction activities only,” namely construction of an approximately 9-mile access road, surface pads, approximately 3 miles of secondary access roads to the pads, and two material sites.

According to Teck, construction activities for Phase I will take place on state land, except for two segments of the access road and two material sites, which wi ll be on NANA land.

Phase II of the project would add additional aboveground infrastructure: a four-season camp, fuel storage facility, maintenance facility, core processing facility, offices, water treatment plants, power generation facility, other support buildings, and a stockpile area for transient waste rock. Underground exploration activities would include developing “approximately 80,000 feet of underground exploration ramps and drifts and executing approximately 300,000 feet of exploratory drilli ng,” Teck explains.

The ultimate goal is to extend Red Dog Operations beyond 2031 and to do so without an extended gap

in production. According to Miller, “With more than 85 percent of the NAB [Northwest Arctic Borough] budget from Red Dog and over 980 shareholder jobs earning about $63 million in annual wages, any gap may have significant negative economic consequences for the region. Any delay has economic implications that will impact direct and indirect workers, communities, the NAB, NANA, and many others depending on the length of shutdown.”

For 2023, Red Dog generated approximately $1.6 billion in revenue, with a gross profit of $408 million, producing 540,000 tonnes of concentrate. Beyond the benefits directly to the region and NANA shareholders, revenue from Red Dog is distributed through the Alaska Native Claims Settlement

Act 7(i) and 7(j) revenue sharing provisions, which means Red Dog money spreads to every region of the state. According to Teck, Red Dog Operations have provided more than $3 billion in royalties to Alaska Native corporations, including NANA, over the mine’s life. Approximately $2 billion of that has been shared with other Alaska Native regional and village corporations.

Hall says the company “is proud to be a major employer in the Northwest Alaska region providing secure, high paying jobs.”

Teck says it is “diligently working to minimize a gap in production” and that securing this permit was key to advancing exploration at Aktigiruq, which “could hold the greatest possibility of extending Red Dog’s mine life, the largest zinc mine in the world.”

According to Teck, Red Dog Operations is an important part of North America’s critical minerals supply chain. Zinc concentrate from Red Dog is shipped to Teck’s Trail Operations in British Columbia, Canada— one of the world’s largest fully integrated zinc and lead smelting and refining complexes—where it is converted into refined products, including germanium, and sold to about 100 customers i n the United States.

Hall continues, saying “We are committed to continuing to work collaboratively with local communities, government, and regulators to responsibly extend Red Dog’s mine life and continue the significant social and economic benefits the operation contribut es to the region.”

By Terri Marshall

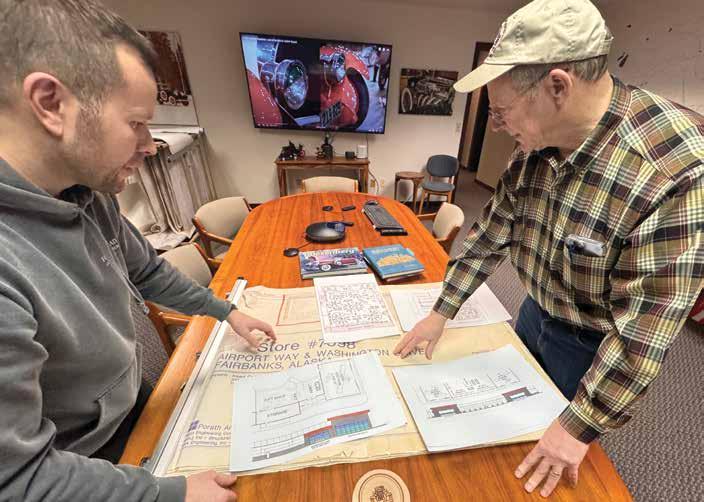

On e of the most popular attractions in Fairbanks is leaving the Wedgewood Resort. The Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum has wowed locals and visitors since opening in 2009. The renowned collection of antique cars and vintage fashions was voted by Alaska Business readers as one of the best museums in the state in 2024, alongside the Anchorage Museum and the Alaska Aviation Museum at Lake Hood. The museum has made its mark, and now it’s moving away from the nest of Fountainhead Development, the owners of the resort property in north Fairbanks.

In 2025, the Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum is moving across Chena River into the former Kmart building on Airport Way, now partially occupied by an Amazon fulfillment center. The new location will expand on the story of Alaska transportation through a partnership with the Interior and Arctic Alaska Aeronautical Foundation, operator of the Pioneer Air Museum currently located in the Gold Dome at Pioneer Park, a few blocks away from the merged museums’ new home.

“Our partnership with the Pioneer Air Museum will allow us to weave together the vibrant histories of aviation and the automobile in the

Far North, presented in vivid detail with rare artifacts and captivating exhibits highlighting Alaska’s transportation pioneers,” says Tim Cerny, Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum founder and owner.

Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum showcases the evolution of automotive technology and cultural shifts of the twentieth century. “In our fifteen years of operation, we have continued to add significant vehicles to our collection as well as enlarging the fashion collection that dates back to the eighteenth century and continues through the post-World

War II era,” explains Cerny. “The clothing tells the story of fashion and design over centuries.”

This “living museum” houses more than ninety-five pre-World War II automobiles, with sixty-five to seventy-five rare automobiles staged at all times. This expansive collection encompasses cyclecars, electric cars, horseless carriages, midget racers, speedsters, steamers, and ‘30s classics.

The fashion component of the museum started with just a few displays and is now considered the most extensive collection of vintage clothing in the Pacific Northwest.

“It was so popular that we decided to expand it,” says Cerny. “My wife, Barbara, is in charge of the fashion component of the museum along with two ladies (both named Connie) who work with her. They focus on acquisition, staging, and building the story of fashion over decades.”

Most recently, the museum team has been working to acquire a group of vintage wax mannequins that were used for clothing displays from 1900 through the ‘30s. “Over the past five years, we’ve been able to purchase about twentyfour individual mannequins modeled after real people at the time they were used,” explains Cerny. “I supposed they would be considered the ‘influencers’ of their time, allowing their images to be used and incorporated into departm ent store displays.”

The exhibits that have been a hit with visitors will tell a more complete story when blended with the Pioneer Air Museum. Cerny says, “We’re very excited about being able to enlarge the story and integrate aviation with the automotive industry and how it changed Alaska.”

“We’re

Tim Cerny, President, Foun tainhead Development

Among the aviation treasures from the Pioneer Air Museum are the Noorduyn UC-64A Norseman Airplane and the remains of Ben Eielson’s plane. Eielson, who delivered the first air mail in Alaska in 1924, died five years later in a plane crash while flying supplies to a ship frozen in the Bering Sea. The new museum will bring such stories to life through displays and interactive exhibits.

“Nowhere in the continental United States did the airplane play such a significant historical role as it did in Alaska,” says Richard Wien, son of Eielson’s contemporary Noel Wien and a legendary bush pilot himself.

“I think it is so exciting that Tim Cerny has agreed to include Alaskan aviation history along with his worldclass auto museum. With the new location, I’m sure it will become a

must-see for visitors and historians.”

The conversation of the possibilities of moving to a new location and blending both museums began during the COVID-19 pandemic, in anticipation of tourism returning to normal. Both organizations were looking forward to something bigger and better.

Cerny says, “The new Fountainhead Transportation Museum will provide exhibit and storage space for over 135 vintage automobiles, several rare airplanes, thousands of vintage fashions, and other rare artifacts. We are very pleased to partner with individuals who work and support the aviation museum and are excited to participate in telling the Alaska transportation story.”

“I am extremely excited about the future of this museum,” says Eric Johansen, president of the board

of the Pioneer Air Museum. “The museum will be a must-visit for residents and visitors alike, who will come away with a real appreciation of the many obstacles overcome by Alaska’s early aviation pioneers.”

Cerny’s company, Fountainhead Development, has been working with Design Alaska to create 90,000 square feet of exhibit space, a restoration area, climate-controlled artifact storage, a gift shop, a reception area for groups, and a catering kitchen.

“The new space will also offer more audio/visual experiences,” shares Karen Wilken, marketing and public relations manager for Fountainhead Development. “With the added space, we will be able to have more interactive exhibits that tell the gritty stories of our

pioneers who paved the way for transp ortation in Alaska.”

As both the automobile and vintage fashion collections continue to grow, Cerny is looking forward to more display space in the old Kmart building. “The new space has 90,000 square feet of floor area in contrast to our existing 30,000 square feet. Currently, we can display up to 85 vehicles from our collection of about 130 vehicles, which requires quite a bit of stock rotation. The new location will give us the space to tell an expanded story of technological development and design elements in the vehicles.”

The museum also vividly details Alaska's rich and colorful auto and transportation history. Its walls display 100 historic motoring photographs illustrating the state’s unique transportation challenges, including the navigation of glacial streams, avalanche chutes, and extremely deep snow.

Cerny says, “We have a great team moving forward, which includes our outstanding docents and our historian, Nancy Dewitt, who wrote three books on transportation in Alaska. She will be back on staff working with us to help develop the integration of the aviation industry.”

Moving delicate aircraft into the new museum requires significant expertise. TOTE Maritime Alaska and the Alaska Railroad recently donated shipping services for two additional historic Alaska airplanes that are being moved from Spokane, Washington to Fairbanks.

In preparation for the move from Wedgewood Resort to the new location on Airport Way, the Fountainhead Antique

“I think it is so exciting that Tim Cerny has agreed to include Alaskan aviation history along with his world-class auto museum... I’m sure it will become a must-see for visitors and historians.”

Richard Wien, Co-founder, Alaska Air Carriers Association

only Alaskan place to stay for charm, culture and cuisine.

Featuring distinctive dining experiences, a full-service espresso bar, unique shops and both men’s and women’s athletic clubs.

Auto Museum will remain open through the tourist season, with the expectation of the last of the larger tour groups concluding the last week of September.

“We will start moving and assembling some of the airplanes in the summer of 2025,” says Cerny. “As for the vehicles, since we are a living museum, the majority of our vehicles are in running condition, and we take them out dr iving every summer.”

Thus, the relocation provides a rare opportunity for an open-air mobile exhibit. Cerny says, “For the transfer, we’ll have several parades of antique cars driving through Fairbanks as we move from the existing museum to the new space.”

The current museum space at Wedgewood Resort will be converted

into a convention center and event space. “We’ve been advocating for a convention center for the better part of two decades,” says Scott McCrea, president and CEO of Explore Fairbanks. “We felt like a convention center was the missing asset to a solid tourism industry here in Fairbanks. Now, with the current location of Fountainhead Auto Museum at Wedgewood Resort being converted to a conference and event space and the recent opening of the 8 Star Events Center space, we will have more optio ns to offer groups.”

As a vibrant year-round destination, Fairbanks tourism stands to benefit from the additional space for meetings. “The economic impact of meetings and conventions can be pretty significant for a community,” explains McCrea. “We’ve seen what it does in terms of economic

contributions to hotels, restaurants, and shopping venues.”

McCrea also expects to benefit from the potential for meetings and conventions in the community’s shoulder seasons. He says, “We have solid summer and winter seasons for tourism, but with this new space, attracting meetings and conferences during the shoulder months like April and October will add a significant economic impact.”

The Explore Fairbanks team is also excited to witness the union of the Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum and the Pioneer Aviation Museum. “The Fountainhead Antique Auto Museum is a gem within our local tourism industry. People who go there are just in awe of its collection,” shares McCrea. “With aviation being so critical to our history and growth as a state, we think this will be an extremely successful union.”

Use your savings at any eligible university, college, vocational school, apprenticeship, or even K–12 public, private, and religious schools.

Answer “Yes” to the Alaska 529 question on the PFD application to contribute half of a PFD into an Alaska 529 account, and you will be automatically entered to win a $25,OOO scholarship account.*

Go online to request a Plan Disclosure Document, which includes investment objectives, risks, fees, expenses, and other

You should read the Plan Disclosure Document carefully before investing O ered by the Education Trust of Alaska. T. Rowe Price Investment Services, Inc., Distributor/Underwriter. *Certain restrictions apply; visit Alaska529plan.com for complete rules.

by Rachael Kvapil

Hy drocarbons are the backbone of Alaska's energy wealth. Oil and natural gas, composed of carbon molecules studded with hydrogen atoms, continue to shape the state’s future. But the state’s rocks may also hold a simpler, cleaner resource.

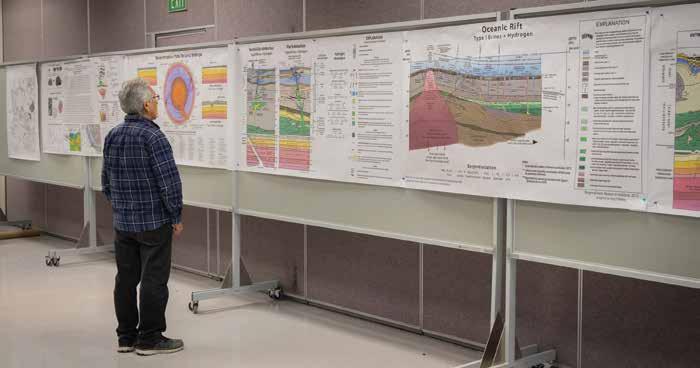

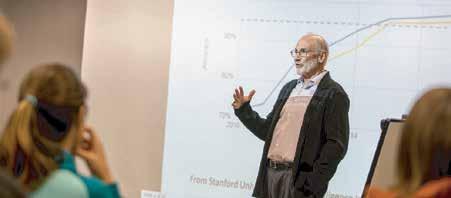

More than 100 people gathered at UAF in October to discuss the potential of geologic hydrogen. This process, different from industrially produced hydrogen, is still in its infancy. However, this isn't stopping key players from sharing information in hopes of discovering a breakthrough that will lead to a viable commercial product.

The first internal combustion engine in 1806 burned hydrogen.

Ever since, the most abundant chemical element in the universe has held potential as the next big energy storage medium. The gas doesn’t count as an energy source, exactly, because humans need to add energy to make it. Either hydrogen is stripped from methane in natural gas or, less commonly, separated from water molecules. When hydrogen recombines with oxygen, some of that energy is released for useful work.

Geologic hydrogen, though, is an energy source. The hydrogen gas forms naturally by geological processes deep within the Earth. Deposits formed from these processes can be accessed and recovered by drilling. Because of its purity, geologic hydrogen is referred to as “natural,” “gold,” or “white” hydrogen.

“It's hard to find a single resource that could have such a big impact on our world in the way of helping our energy transition to move forward,” said Dr. Mark Myers, Commissioner of the US Arctic Research Commission, during his opening remarks at the Geologic Hydrogen Workshop 2024 hosted by UAF.

Myers says that Arctic communities need additional sources other than electricity to meet energy demands, so the distribution of geologic hydrogen has the potential to fuel areas that don't have access to oil or gas.

Though geological settings conducive to natural hydrogen may exist in Alaska and the broader Arctic regions, geologists have yet to fully study and assess their potential. The workshop was a

step forward in determining what is needed to develop a sustainable research effort in Alaska and identify the policies and regulations required for research, exploration, and development. Presenters also outlined the utility, economics, storage, and transportation realities that are part of making natural hydrogen a viable fuel source in a competitive energy market.

Michael Sfraga, Ambassador-AtLarge for Arctic Affairs with the US Department of State, says energy plays a significant role in the national strategy for the Arctic region. This strategy comprises sustainable economic development, environment and climate, national security, and international cooperation and governance. In his opening remarks to conference attendees, he identified seven drivers of change in the

Arctic that also affect other parts of the world: climate, commerce, commodity, connectivity, community, cooperation, and competition. As he expounded on these drivers, he pointed to recent events that disrupted the energy industry, such as the war in Ukraine. Likewise, he emphasized working together to navigate these seven Cs so everyone benefits from resource development.

“Energy filters through everything my department has addressed,” Sfraga said. “In meeting with allies and friends, energy comes up in every discussion. That's why this is really important.”

The cross-section of presenters covered the spectrum of energy stakeholders. Representatives from private industry, Alaska

Native organizations, government, and regulatory and resource management agencies attended alongside international experts on geologic hydrogen and Alaska geology. Researchers from the US Geological Survey gave multiple presentations that touched on different aspects of geologic hydrogen, such as systems, generation, Alaska composition and distribution, and current research. Other presenters included the US Department of Energy National Laboratories, the US Department of Energy Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E), The University of Texas at Austin’s Bureau of Economic Geology, Cornell University, Alaska Department of Natural Resources Geological and Geophysical Surveys, and the Geological Survey of Finland.

Much of the discussion surrounding the identification of geological hydrogen sources was technical and benefitted from background knowledge of the processes. However, presenters provided multiple visuals to illustrate their research and projections.

Eric

Marshall | UAF Geophysical Institute

“All of this is still in its infancy… The Department of Energy is focused on stimulation and engineering. We are not looking at exploration at the time.”

Douglas Wicks, Program Director, Advanced Research Pr ojects Agency-Energy

Much of the information presented was technical and required a background knowledge of the chemical and geological processes by which natural hydrogen can be continuously generated. In a nutshell, certain rocks can undergo mineralogical and chemical reduction (an atom gains electrons) or oxidation (losing electrons) when they encounter water. The process called serpentinization moves ironrich rock from the oceanic crust up through tectonic processes, and when it meets with water, iron is released while water is reduced to hydrogen. Much of what is known about the geological characteristics that create these reactions in Alaska is based on what has been found in Canada, Russia, Australia, Germany,

New Zealand, and other places with similar geologic conditions.

At least fifty companies are actively exploring and extracting geologic hydrogen, yet the most talked-about producer is Bourakébougou, a village in Mali. Locals drilling a water well in 1987 accidentally discovered a deposit when a villager sparked an explosion by lighting a cigarette near a breeze emanating from the hole. The breeze turned out to be a steady stream of natural hydrogen gas. To prevent additional accidents, the hole was cemented shut until 2012, when a Canadian company now known as Hydroma tapped the hydrogen to supply residents with electricity. From 2017 to 2019, Hydroma drilled twenty-four wells in the Bourakébougou fields.

Though many workshop presenters referred to the Bourakébougou as an example of what's possible, they also were realistic about the discovery and scale of the project. The shallow reservoir layer provides 5 to 50 tons of natural hydrogen per year (the equivalent of 0.3 to 3 barrels of oil per day) and less power output than a tenth of a single mediumsized wind turbine. However, this finding and other prospects in Albania and France spurred additional research and exploration in Europe, Asia, Scandinavia, South Ame rica, and Australia.

“The United States is late to the game,” said US Geological Survey Research Geologist Geoffrey Ellis in his presentation on the historical

contexts of geologic hydrogen and an overview of th e rest of the world.

Intermixed with scientific presentations were additional conversations about upcoming funding for research and exploration. ARPA-E has provided pockets of funding through its Geologic Hydrogen Exploratory Topics project categories. In February, ARPA-E funded $20 million for sixteen projects across eight states that focus on accelerating the natural subsurface generation of hydrogen. The awarded projects are from a mix of universities, national labs, and private businesses conducting early-stage research and development to advance low-cost, low-emissions hydrogen. All the funding recipients awarded since 2023 are in the Lower 48.

“All of this is still in its infancy,” said Douglas Wicks, ARPA-E program director, in his presentation. “The Department of Energy is focused on stimulation and engineering. We are not looking at exploration at the time.”

Several companies operating in Alaska are funding their own research into hydrogen conversion, generation, storage, and exportation. Representatives from Alyeschem, Amp Energy, Treadwell Development, and Stillwater Critical Minerals presented different theoretical models, cost analyses, and timelines that forecasted the market feasibility of geologic hydrogen anywhere from ten to twenty or more years in the future.

Economics and logistics aside, there are other challenges that producers, legislators, and other entities will need to tackle before major exploration occurs in Alaska. The first

is land ownership. Regional and village corporations collectively own 44 million acres, much of which contain geological formations well-suited for natural hydrogen. The circumstances in which exploration occurs on Native lands remain to be seen. Likewise, the regulations that guide drilling, production, and transportation are undefined. Key Alaskan legislators who attended the conference say the state's experience developing oil and gas regulation will guide the process, but it doesn't necessarily mean the results will be the same.

Ultimately, experts agree that it will take a big find or a decrease in exploration costs before leaders invest significantly in geologic hydrogen. They encouraged everyone to keep moving forward with research and development so that everyone is ready when the opportunity comes.

in-person degree or certificate programs, or a fully online program with UAF eCampus. Empower them to get one step closer to their career goals — on their schedule, wherever

• Online degrees with flexible schedules for rotational workforces.

Projects in architecture and engineering, be they monumentally large like Project 80s buildings or tiny homes in Petersburg, are manifestations of the talent, teams, techniques, and tools that make them. For talent, look to the nominees for the Engineer of the Year awards for 2024. They bolster teams ranging from firms like Design Alaska to associations like the Society for Marketing Professional Services, a network of business development experts who connect firms to clients.

Techniques include the specialized knowledge that goes into fire protection engineering or interior design—knowledge that must stay up to date with the latest innovations. Those new tools might be 3D printers that squirt out concrete walls or AIdriven software that can amplify a small company’s reach.

But enou gh tease; let’s get to the Ts.

By Scott Rhode

In terior design deserves to be taken seriously. Dana Nunn, interior design director at Bettisworth North, would like to see more respect for her profession.

“Public perception is largely that interior design is a luxury for the very elite who can afford it at home. Or it is picking paint colors and doing the surface things,” Nunn says.

Basic cable TV shows made some Alaskans look like heroes: crabbing crews, gold dredgers, ice road truckers. But interior designers had to endure the shame of Trading Spaces . Not every project involved a bale of straw glued to a living

room wall, but more than zero did. That’s tough for a hard-working professional to live down.

Nunn says people only notice the surface of a designed space.

“Everything else we do is behind that,” she says. “Finishes is less than 5 percent of what an interior designer does.”

The percentage is the same at Anchorage-based MCG Explore Design, according to the designers there.

“Anyone can pick a paint, but not everyone understands what it will

do to the space,” say MCG principal interior designers Melissa Pribyl and Cara Rude. “We also space plan, design ceiling plans, and coordinate lighting and electrical needs with our engineering consultants. We understand the building codes and how to properly egress occupants, and we design for inclusivity and allow for individuals of all ages and abilities to safely interact with the space.”

When not choosing fabric or paint swatches, designers are busy with interior space analysis, planning and design, non-bearing interior construction drawings, furniture

and finish specifications, and management of interior construction and alteration projects in public and private buildings. Pribyl and Rude explain that interior designers must comply with building design, construction, and life-safety codes.

Registered interior designers are qualified by education, experience, and examination to provide these services.

Nunn adds, “We don’t design the electrical system for the lights, but we communicate to the electrical engineer what kind of lighting we need, where we’d like it placed, what kind of surface they’re interfacing

“Architecture is an age-old profession, and interior design (similar to landscape architecture) is a relatively new profession… That barrier has been falling away pretty slowly but consistently since the late ‘80s.”

Building thriving communities, together.

f Civil Engineering

f Structural Engineering

f Mechanical Engineering

f Electrical Engineering

f Fire Protection Engineering

f Corrosion Control Engineering

f Alternative Energy

f Commissioning

f Landscape Architecture

f Process Engineering

f Process Safety Management

f Trenchless Technology Engineering

with. What are the functions we’re supporting, and what kind of controls do we need?”

As she puts it, an architect suggests where lights should go, and the electrical engineer plans the wiring and ensures proper light levels. Nunn was trained to calculate light levels, and she’s done them on smaller projects, but at an integrated firm with engineers on staff, she usually doesn’t have to.

Nunn is less involved in drafting and modeling these days; as a supervisor, her role is to develop a project's program, contribute to the concept, and influence the design direction, while also overseeing schedules and budgets. After twenty years as a designer, she says, “I have projects in over ninety Alaska cities and villages, and I have nearly seventy unique project types in my twenty-one years of working in Alaska.” Those types range from morgues and water treatment facilities to theaters and museums.

The purpose of a building guides the designer’s approach. The first step, according to Pribyl and Rude, is a program for the space, setting goals for how occupants will use it and how the shape of the structure supports those goals. Interior designers collaborate with other professions to meet these goals.

“Do they need a sink? Does the icemaker need a floor drain? If yes, you will need a mechanical engineer. Do the additional electrical outlets max out the existing electrical load? If yes, then you will need an electrical engineer. Do they want to have shelving installed above 6 feet? If yes, they need a structural engineer for seismic stability,” say Pribyl and Rude. They compare the collaboration to the different positions on a soccer team.

When collaboration goes wrong, the results might be public restrooms that are inaccessible to all users, flooring with measurably high rates of slip-and-fall accidents, or fabrics that break down under repeated cleanings, which can be an infection hazard in healthcare or restaurant settings.

A skilled interior designer minding the net (to extend the analogy) can keep these mistakes from slipping through.

Surface finishes and space programming are also the domain of architects, who might have their own ideas. Nunn’s colleague at Bettisworth North, architect Heather Kapala, welcomes the overlap. “You want the outside to speak to the inside,” Kapala says.

Literally, in some cases: Nunn notes that interior designers might sometimes coordinate with landscape architects to unify indoor and outdoor spaces.

Pribyl and Rude call the relationship a “fluid process with a collective goal.” A project needs both to succeed.

Pribyl says, “Architecture is broad in scope, but specializations like landscape architecture and interior design have evolved to the point where they are now recognized for their unique expertise. This parallels the different specialties of engineering, such as electrical, mechanical, civil, and structural engineering.”

Rude adds that most of the world uses the term “interior architect” instead of interior designer.

“Architecture is an age-old profession, and interior design (similar to landscape architecture) is a relatively new profession,” says Nunn. Historically, interior decorators were tradespeople hired by architects. As the specialty has professionalized, Nunn says, “That barrier has been falling away pretty slowly but consistently since the late ‘80s.”

Interior designers and architects now meet eye to eye as certified professionals. A designer can earn a fouryear college degree and take the three-part exam from the Council for Interior Design Qualification that focuses on health, safety, and welfare codes.

Kapala says, “Interior design and architecture should not be in a vacuum, separate from each other. The more

that the wall between is brought down, the better the project ends up being.”

“The best projects are when we’re working together and not working siloed,” adds Nunn. “The client experience is better. The project outcome is better.”

As an example of collaboration, Kapala notes that she and Nunn recently attended a conference together, and they both learned about accessibility in design.

“There’s overlap in the continuing education we do, between interior designers and architects, so that helps keep that bridge alive. We’re both learning about the same new things,” Kapala says.

Much of an interior designer’s working hours are occupied with project-based research, literature reviews, and seeing what’s available on the market.

“It’s about building your bank of knowledge and resources. When the opportunity strikes, you’re prepared to offer the best,” Nunn says.

Kapala adds, “It’s really satisfying when a client is like, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if we had something like…?’ and you’re, ‘Actually, I do.’”

Attending conferences and other continuing education keep designers abreast of the latest industry innovations.

Pribyl cites some new techniques that MCG is adopting, such as biophilia and biomimicry, environmental psychology, and virtual renderings. Pribyl and Rude were the first designers in Alaska certified in the WELL Building Standard, a 2013 rubric for best practices in environmental quality and occupant wellbeing.

Bettisworth North’s offices in Anchorage serve as a showcase for the latest interior design features. Nunn says clients can visit to see how certain features might work, from the sliding partition panels resembling a birch forest to the seamless threshold between carpet and wood flooring.

The office also demonstrates an active acoustic system in the ceiling. “We have it everywhere, and we have it zoned. Our conference rooms and small meeting rooms are in one zone, so we can turn it down a little bit more,” Nunn explains. “And we have another zone in what we call our living room—our kitchen area and design lab—because those are the most rambunctious. And we have the open office space; it’s turned up a little more there.” The system is not noise canceling, she clarifies, but tuned white noise.

Whatever innovations might pop up next, the skilled interior designer is the first to know.

Every certified designer working in Alaska had to bring their skills back into the state. Although engineering degrees are available in Alaska, the state has no interior design school (nor architecture, for that matter).

Furthermore, the state does not yet recognize interior designers as a licensed profession, but Nunn is trying to change that. She is urging legislators to pass a bill that would add interior design to the professions overseen by the Board of Architecture, Engineering, and Land Surveying. It would not mandate that designers register, but those who do would be allowed to practice independently.

If passed, Alaska would join fifteen states that allow designers to practice independently; a dozen other states regulate the professional certification of designers.

Nunn, for example, is registered in Texas, but she cannot practice independently in Alaska. “If I want to practice in the public realm—impacting public health, safety, and welfare—I have to have the oversight and over-stamp of an architect,” she says, acknowledging that this is less of a problem at an integrated firm like Bettisworth North.

The same goes for MCG, except that designers would be able to sign and author their own work.

Rude says, “After twenty-two years of interior design, I will finally author work in my home state of Alaska. As a fine artist, there has never been a time I didn’t sign my work or had someone add their signature after a critique.”

Professionalizing the field, she says, would create an Alaska-hire incentive for professional interior design and attract high-quality design talent to Alaska, as students studying Outside can return home for career opportunities.

However, the legislation introduced last session failed to pass the Alaska House or Senate, and not for the first time. “We’ve found that understanding and recognizing the relevance and the rigor of the educational path is lacking,” Nunn says of the bill’s opposition.

Although architects have voiced concern that independent interior designers would take business away from them, Nunn doesn’t see it that way. “There’s so much work in Alaska. If you do good work and maintain your client relationships, then there’s no threat,” Nunn says.

At MCG, Rude has the support of her colleagues. “Our partners who are architects are in full support and recognize the growth and expertise of interior design,” she says. “I have high hopes the system will soon reflect this.”

Professionalizing interior design is “sweeping the country,” Nunn says, but the Alaska legislation has taken seven years so far. That’s not an uncommon timeframe, Nunn observes optimistically.

“I hope it’s not another seven years... We’ll see how it goes.”

How Petersburg is tackling its housing shortage

By Katie Pesznecker

Li ttle Norway has a big problem with a tiny answer.

The Petersburg Borough is facing mounting pressure to address a lack of affordable and available housing, a challenge that threatens local growth and stability.

Petersburg is known for its natural beauty, rich Norwegian heritage, and strong commercial fishing roots. The quintessential island community is a residential draw for people seeking small-town life amid stunning Southeast scenery. But the limited availability of homes has capped the population at about 3,000.

In 2023, the Petersburg Borough took a bold step by introducing the Permit-Ready Accessory Dwelling Unit (PRADU) program. This initiative provides pre-approved designs for tiny homes, offering a streamlined path for residents to create

additional housing—and generate income—on their properties. The innovative program has the potential to positively alleviate the small town’s housing crunch, one tiny home at a time.

One House at a Time

Petersburg’s housing shortage is not new. For decades, the market has been tight, with limited rental and purchase options. According to the Petersburg Borough Housing Needs Assessment, prepared by Agnew::Beck Consulting in 2023, the borough needs 316 housing units over the next decade—133 new constructions and 183 rehabilitations—to meet demand across all income levels.

The study revealed several critical challenges facing Petersburg’s housing market. With a vacancy rate

“Petersburg is a special place… The PRADU program shows what’s possible when a community comes together to solve its challenges.”

Hildie Cain Architect

Systemcenter Alaska delivers innovative furniture, storage, and design solutions tailored to enhance your team’s performance potential. As your trusted Haworth dealer, we create efficient, space-saving, and inspiring workplaces that prioritize comfort, productivity, and growth.

Contact us today for a free consultation to design a workspace that works for you.

systemcenter.com/alaska

“In our minds, we might build hundreds of these, and we didn’t want everyone’s backyard to look the same. The idea was to make it affordable, make it look nice, make it fit in with the community.”

Hildie Cain Architect