Beischer President, CEO & Director

United. Inspired.

Beischer President, CEO & Director

United. Inspired.

Construction Machinery Industrial and Epiroc

Boomer E3

In the World – The best construction equipment technology. In Alaska – The best sales and product support lineup. In Your Corner – The Winning Team.

E3

Boomer E3

Alvin Ott,

Boomer E3

Boomer E3 Ott,

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

Boomer E3

technology. lineup.

Epiroc technology. support lineup.

technology. lineup.

Epiroc technology. lineup.

technology. support lineup.

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Boomer E3 Steel

Boomer E3

• Steel

Construction

• Steel

Steel

Boomer E3 Steel

Surface Rigs - ··Underground Rigs ·- Drill bits - ·Steel

• Steel

Boomer E3 Steel

Boomer E3 bits

Boomer E3 Steel

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Anchorage (800) 478-3822 Juneau (907) 802-4242

Rigs • Underground

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Construction Machinery Industrial and In the World – Epiroc, The best Mining equipment In Your Corner – The Winning Team. In Alaska – CMI, The best sales and product support

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales Paul Larson, Juneau

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 Juneau (907) 802-4242

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228 technology.

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228 technology.

(907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

(907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Juneau (907) 802-4242

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228 technology.

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Juneau (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 Juneau (907) 802-4242

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

epiroc.us

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228 Epiroc technology. lineup.

epiroc.us www.cmiak.com (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

www.cmiak.com

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

epiroc.us

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales

www.cmiak.com

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us www.cmiak.com (907) 563-3822 (907) 802-4242

Surface Rigs • Underground Rigs • Drill Anchorage Juneau

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Alvin Ott, Fairbanks Mining Sales Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Anchorage (907) 563-3822 Juneau (907) 802-4242

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us www.cmiak.com

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

epiroc.us www.cmiak.com

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us www.cmiak.com

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Fairbanks (907) 931-8808 Ketchikan (907) 247-2228

epiroc.us www.cmiak.com

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

Mining Sales epiroc.us

www.cmiak.com Anchorage (907) 563-3822 Juneau (907) 802-4242

epiroc.us

Paul Larson, Juneau Mining Sales epiroc.us

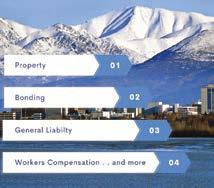

In Alaska, running a business is as unpredictable as the open sea. With First National, you’re equipped with an experienced team of local experts and innovative tools to navigate toward a bright future. From facility financing to payroll processing, we’re here to help Alaska businesses succeed.

Shape Your Tomorrow

Discover how First National empowers businesses like Insatiable Fisheries to thrive in Alaska’s unique economic waters.

42 CATCHING THE NEW WAVE

AI reshapes oil and gas exploration and development

By Rindi White

56 THE MINERAL LEAGUE

Trading cards to clip, keep, and collect

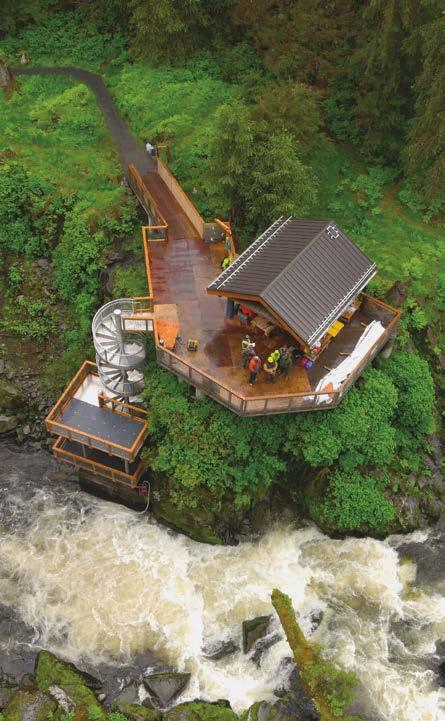

62 CANADA AND ALASKA, BOUND BY RIVERS

Unified alarm about transboundary mining

By Dimitra Lavrakas

70 MAKING THE GRADE

Lumber training builds supply for local forest products

By Rachael Kvapil

76 “OUR STORIES TO TELL”

Southeast invests in cruise ship infrastructure

By Katie Pesznecker

CORRECTION: Page 86 of the October 2024 issue lists the name of Great Northwest’s CEO incorrectly. It is A. John Minder.

48 MISSION: CRITICAL

Steady progress by Graphite One and Nikolai nickel

By Amy Newman

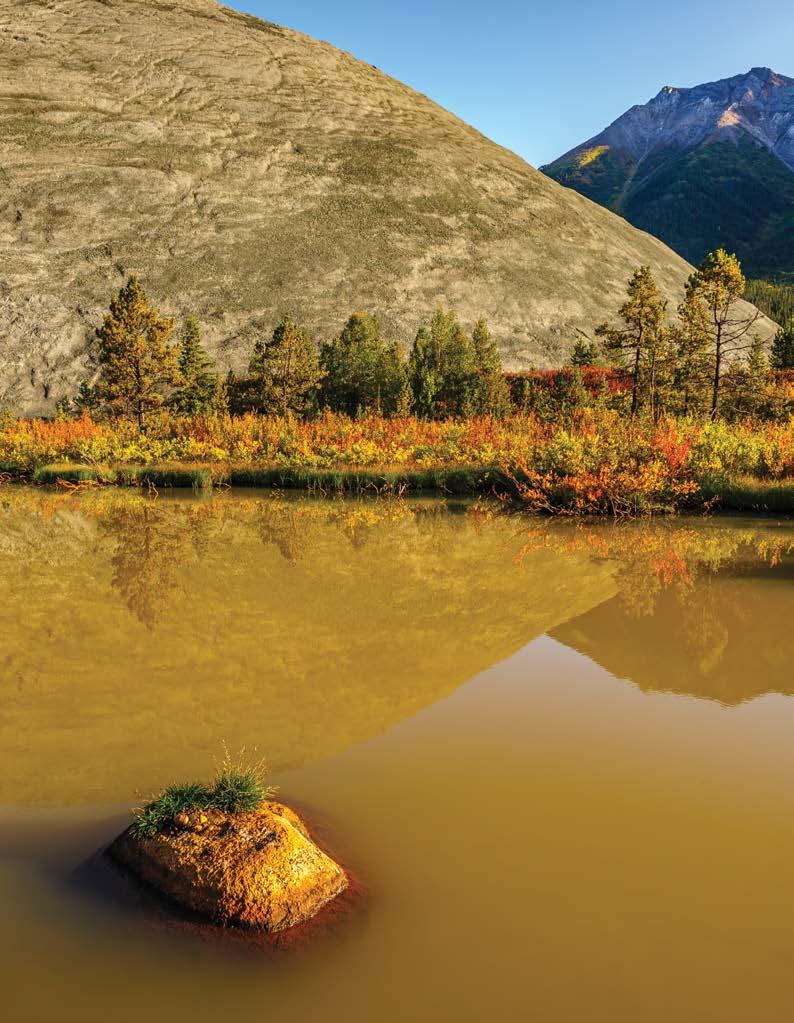

Minerals are only part of Alaska’s natural resources, which is why the annual special section has grown to encompass other industries beyond mining. The pages within contain coverage of oil and gas, fisheries, timber, and tourism, yet mineral development remains at the core.

Now that Manh Choh has joined the other six mines in active production, readers can familiarize themselves with the industry with a set of trading cards. In addition to the seven on the roster, more mines are in the developmental leagues, so to speak. One of those projects in the advanced exploration phase is Graphite Creek; in baseball terms, it’s in the Double-A level, preparing to advance to Triple-A before joining the majors.

An example of a Single-A project, then, is Nikolai, a prospect near Paxson. Greg Beischer of Alaska Energy Metals is leading the exploration for nickel and other metals there, hoping to bring Nikolai to the big leagues.

Troy

MCWILLIAMS GOLD CLAIM

Talkeetna, AK

$25,000,000 | 881± Acres

PASSAGE ISLAND

Seldovia, AK

$4,950,000 | 44± Acres

SCHULTZ FARMS

Delta Junction, AK

$6,750,000 | 5,592± Acres

$3,500,000 | 604± Acres

Mining is relatively simple. Dig into the ground, extract a valuable resource, refine it, sell it. This is why there are historic examples around the world of individuals or small groups making a fortune on a commodity with a few shovels, the determination to keep digging, and a rich deposit.

But that sort of rags to riches through a pickaxe story happens less and less: many of the “easy” deposits have been found and exhausted, and what used to be a wildly unregulated industry is now highly regulated. Even into the 20th century, mines were depleted and then literally abandoned, with owners and operators leaving equipment, infrastructure, and garbage behind. Federal regulation now requires mine owners to have a plan that explains how the project will be constructed, operated, and reclaimed. For example, the January 2023 Manh Choh Project Reclamation and Closure Plan Revision 1 is 86 pages and details the plan for reclaiming Alaska’s newest gold mine, including an estimated reclamation cost of approximately $63.5 million.

Alaska mines permitted and operated under modern regulations thus far have a stellar track record: Usibelli Coal Mine has engaged in reclamation activities contemporaneously with its mining activities, which means early dig sites have already been returned to a natural state even as new areas are mined. Kinross, which operates Manh Choh Mine, successfully reclaimed the True North Mine, which operated from 2001 through 2004. In 2009, Kinross started the reclamation process, which included grading and recontouring 149 acres, seeding and fertilizing 270 acres, planting vegetation on 52 acres, and removing all mining buildings; the majority of that work was completed in 2014. Kinross then monitored the site, ensuring the long-term stability of the landscape, until it returned the land to state control in 2020. Four years of mining—eleven years of reclamation.

Expecting mines to operate in a way that is safe for people, the environment, and the future is good, but it does complicate the “dig, refine, sell” process. As that process becomes more complicated, the question of whether the resource is worth the work gets more complicated, as well.

Add on top of that global commodities markets fluctuating in response to warfare or political conflicts; changing demand for advanced technologies and energy solutions; and the fact that regulations can change, or administrations can change how to read and enforce those regulations, and it becomes clear how a mine project today can take decades to research, permit, and—maybe, just maybe—invest in.

Regulations are necessary, global markets are out of any one entity’s control, and technology takes unpredictable jumps all the time. But! For those who value and support Alaska’s mining industry, there is one place where you can make a difference: who is administering and enforcing those regulations.

It’s November. There are important decisions to be made about who will be making decisions for all of us. Please research the individuals and issues that you will be asked to vote for or against. Your voice matters, and so does your vote.

Tasha Anderson Managing Editor, Alaska Business

VOLUME 40, #11

Managing Editor

Tasha Anderson 907-257-2907

tanderson@akbizmag.com

Editor/Staff Writer

Scott Rhode srhode@akbizmag.com

Associate Editor

Rindi White rindi@akbizmag.com

Editorial Assistant

Emily Olsen emily@akbizmag.com

Art Director

Monica Sterchi-Lowman 907-257-2916

design@akbizmag.com

Design & Art Production

Fulvia Caldei Lowe production@akbizmag.com

Web Manager

Patricia Morales patricia@akbizmag.com

SALES

VP Sales & Marketing

Charles Bell

907-257-2909

cbell@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager

Janis J. Plume 907-257-2917

janis@akbizmag.com

Senior Account Manager

Christine Merki 907-257-2911

cmerki@akbizmag.com

Marketing Assistant

Tiffany Whited 907-257-2910

tiffany@akbizmag.com

President

Billie Martin

VP & General Manager

Jason Martin 907-257-2905

jason@akbizmag.com

Accounting Manager

James Barnhill

907-257-2901

accounts@akbizmag.com

CONTACT

Press releases: press@akbizmag.com

Postmaster:

Send address changes to Alaska Business

501 W. Northern Lights Blvd. #100 Anchorage, AK 99503

By Terri Marshall

Fo r forty years, federal courts have applied a legal test known as “Chevron deference” when reviewing federal agency actions. Originating from a 1984 decision of the US Supreme Court in Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., the ruling required federal courts to defer to a federal agency if the court believes the statute in question is ambiguous and the agency’s interpretation was reasonable—even if the court would interpret it differently.

On June 28, 2024, the US Supreme Court reversed that doctrine. The decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo cut back sharply on the power of federal agencies to interpret the laws they administer and ruled that courts should rely on their own interpretation of ambiguous laws. In overruling Chevron, the Supreme Court made clear that it is the responsibility

of federal courts—rather than federal agencies—to interpret the law.

Chief Justice John Roberts Jr. explained in the opinion that Chevron “defies the command of” the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), the law governing federal administrative agencies, “That the ‘reviewing court’— not the agency whose action it reviews—is to ‘decide all relevant questions of law’ and ‘interpret… statutory provisions.’... It requires a court to ignore, not follow, ‘the reading the court would have reached’ had it exercised its independent judgment as required by the APA.”

In a concurring opinion, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch described the court’s action as placing a “tombstone on Chevron no one can miss. In doing so, the Court returns judges to interpretive rules that have guided federal courts since the Nation’s

“Federal policies about land use are going to be very heavily determined by federal bodies, whether that be by litigation or regulatory agencies. So who gets to decide the rules of the road and what that looks like in timing, costs, and process?”

Bonnie Paskvan

Partn er, Dorsey & Whitney

“It’s hard to overstate the magnitude of this change in process… Decisions may be better or worse coming from the court. I think they’re likely to be more expensive and potentially slower.”

Bonnie Paskvan Partn er, Dorsey & Whitney

founding.” Gorsuch had a personal tie to the case: his late mother, Anne Gorsuch, was administrator of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the original defendant sued by the Natural Resources Defense Council. She had loosened Clean Air Act enforcement, but a circuit court ruled against her. That ruling was written by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who ended up serving alongside Neil Gorsuch for a few terms on the Supreme Court.

Chevron, which helped pioneer the oil industry in Alaska, intervened in the case along with the American Petroleum Institute, Chemical Manufacturers Association, Rubber Manufacturers Association, American Iron and Steel Institute, and General Motors. As an intervenor, Chevron appealed to the US Supreme Court to uphold EPA’s industryfriendly interpretation

In Loper Bright , Alaska joined with twenty-six other states to file an amicus brief asking the Supreme Court to reverse Chevron deference.

Michael Drysdale, a partner at Dorsey & Whitney in the areas of environmental law and general litigation, notes, “Chevron deference has been cited more than 17,000 times since its enactment in 1984, making it one of the most cited Supreme Court decisions. But this court has been skeptical of Chevron for several years. They made a point of saying they haven’t cited it since 2016. It has still been a very important piece of precedent for the lower courts that are looking to deal with the issues that come up.”

The US Supreme Court’s ruling generally means that it is now much easier for courts, particularly lower courts, to overturn federal rules. “If they find an ambiguity, they now are

not supposed to defer to what the agency says. The court may listen to what the agency has to say, but won’t necessarily afford it any extra weight,” says Drysdale. “So the likelihood that the agency and the court land in the same place is now a lot lower.”

The US Supreme Court’s decision will likely have far-reaching effects across the country, but in Alaska those effects are magnified.

Bonnie Paskvan, a Dorsey & Whitney partner who leads the firm’s Anchorage office, has significant experience working with Alaska Native corporations and municipalities. Paskvan believes Loper Bright will have a disproportionately large impact on Alaska.

says. “We are heavily dominated by federal regulation all over the state, whether it be via federal funding or federal oversight for mining, fisheries, or any other large, heavily regulated projects. It just seems likely there will be a bigger impact here than in some other states where those factors are not at the forefront. Also, about 65 percent of Alaska’s land is federally owned and managed, so federal policies about land use are going to be very heavily determined by federal bodies, whether that be by litigation or regulatory agencies. So who gets to decide the rules of the road and what that looks like in timing, costs, and process?”

In a recent press release, Alaska Attorney General Treg Taylor noted his approval of the Loper Bright decision. “Federal agencies have used Chevron

agencies’ actions all while moving to improperly expand their discretion and authority. By getting rid of Chevron , the Supreme Court has restored the separation of powers. Under our system of government, it is a court’s job to offer a final interpretation of the law, not the job of federal agencies,” Taylor wrote.

Anchorage attorney Christopher Slottee, an industry group leader for Schwabe with a focus on Native corporations and natural resources, anticipates a mixed response to the reversal of the Chevron deference.

“For Native corporations, it’s going to be dependent on the specific situation or the specific regulation. Some Native corporations are going to be very in favor of challenges to regulations that restrict development of certain resources because they want to have more freedom to develop the natural resources on their lands,” says

Slottee. “On the other side, there’s certainly going to be some Native corporations and some Native groups that are opposed to striking down those regulations because they want to see them in place to preserve the traditional habitat or traditional nature of their Alaska Native lands. It’s going to be specific both as to the regulation but also to which side someone is on.”

Alaska Governor Mike Dunleavy stated his approval of the Loper Bright decision. “Ever since statehood, Alaska has had to continually fight just to try and hold on to what was already given—fish and game management, submerged lands, land entitlements, resource development, the list goes on. This constant deference given to federal agencies has made the fight that much harder and resulted in Alaska being treated as a volleyball going back and forth depending on who’s in the White House. Our legal rights as a state should not depend on who’s in office—those rights either exist or they don’t. The US Supreme Court’s decision at least gives us a fair chance to fight

back and secure the rights we were promised,” Dunleavy says.

Loper Bright does not automatically nullify all federal regulations in a single stroke. Rather, it rebalances the scales when regulations are challenged in federal courts. Recent court decisions apart from Loper Bright provide a glimpse into the potential challenges environmental agencies will face in a post-Chevrondeference legal environment.

“With regard to the Clean Water Act, we’ve seen the US Supreme Court, even this past session, restrict the ability of the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) to regulate certain aspects of waters. We expect to see significantly more challenges to EPA, USACE, and other natural resources governing agencies from this, and they will have a better chance to succeed under this new regime,” says Slottee. “We haven’t seen those specific results to date, but we know that they are coming, and they are coming quickly.”

Drysdale expects EPA to be most affected. “They have so many regulations that affect so many economic activities and many of those regulations are controversial,” he says. “There are many other areas that will be very affected, like telecommunications and cyber security and the rules for those industries. When you think about fast-moving industries, it’s going to be much harder to manage those because the statues are often way behind.”

Drysdale notes an additional example of the problems this new process could present. “Imagine you are the Biden administration or a future Democratic administration and you want to do something aggressive to fight climate change. And you’re looking within your authority, whether it be Clean Air Act or any other federal act, and you say, ‘I want to accomplish this policy to fight climate change,’ while it’s not clear on whether you can do that. Under Chevron you could say, ‘Well, is my interpretation reasonable?’ Yes, go forth and enact. Now it’s like, well, what is a judge in Texas going to think about it?”

Your system is safe and smart on Alaska’s most advanced network.

GCI.COM/BUSINESS

Attorneys face numerous uncertainties now that the Chevron deference is overturned. “It’s hard to overstate the magnitude of this change in process,” says Paskvan. “Decisions may be better or worse coming from the court. I think they’re likely to be more expensive and potentially slower.”

Drysdale notes the importance of distinguishing between how good a rule is and how clear the rule is. “In many cases, there may be a rule that you don’t like as a business, but if it’s clear you can deal with it in terms of your pricing and your contract terms, et cetera. Consider OSHA [Occupation Safety and Health Administration] regulations: companies complain about those all the time. But if they’re clear, they can deal with them,” he says. “An unclear rule, whether it’s a good or bad rule, poses problems over and above that. You just don’t know whether what you’re doing is going to ultimately be OK and whether the investments you’re making

in compliance are going to be worth it.”

Attorneys recommend remaining proactive. “I think the biggest impact of this ruling is that it’s going to raise a lot of uncertainty. We just don’t know how the removal of Chevron is going to shake out yet, and we’re not going to know for a year or two until these initial challenges are tested and we can see the impact,” says Slottee. “What I’ve been saying to my clients is, let’s look at your regulatory regime, let’s try to find areas in which we can take advantage of this and stay aware of areas where we need to be concerned about attacks under this new regime.”

Slottee adds, “It’s best to be prepared, monitor what’s going on, and see what the potential consequences are.”

Time will provide more insights into the outcomes of Loper Bright across the country and in Alaska. One factor to watch is how the agencies respond. “We’re not going to know how federal agencies will respond for a while because they are big entities. It takes

them a while to change course, and combined with a new administration, there could be a wholly different agency approach as well,” explains Slottee.

Drysdale also notes, “The significance of this case is now much greater today than it would have been if the same decision had been made in 1984, due to the difficulty of passing legislation today. The simple solution to any error is to obtain statutory authority. Congress can always fix any problem that a court may have with a rule, but Congress doesn’t often pass laws anymore, so that’s not really a solution.”

Despite the uncertainty, Drysdale doesn’t think Loper Bright will necessarily result in more litigation. “Almost every major rule gets litigated these days anyway. But what it does do is it makes it more likely that the rules will be overturned,” he says, “so the agency will have to take multiple bites of the apple, and it will be a much longer period of uncertainty. This could go on for years.”

By Lincoln Garrick

Fo rty-four months is the median criminal sentence length in Alaska, according to 2023 data from the US Sentencing Commission. That’s 1,320 days, which is a significant chunk of any life to put on hold, and it also creates a work résumé with an almost four-year gap. Alaska releases around 7,000 people annually from its correctional facilities, people who have spent time reflecting on mistakes and gaining skills to get prepared for reentry into the Alaska workforce to live again within our community.

More than 5,000 people are currently incarcerated in Alaska's justice system, and many more are tracked under electronic monitoring, parole, probation, or in halfway houses. The state's incarceration rate is 718 per 100,000 people, as compiled by the Prison Policy Initiative in the report Mass Incarceration: The Whole Pie 2024. This is higher than both the US national average of 531 per 100,000 and all other countries, with El Salvador coming in closest at 605 per 100,000, according to a January 2024 study by global research firm Statista.

However, incarcerated does not mean convicted and sentenced. According to data from the Alaska Justice Information Center, roughly half of Alaska Department of Corrections (ADOC) facilities contain individuals awaiting trial and who do not yet have a criminal record.

A criminal record, not to be confused with an arrest or police record, is a record of a person's criminal history, and it is established only when a person is convicted. While a period of incarceration is generally finite, a criminal record can follow people for their whole lives. Criminal records are often viewed as "collateral consequences," describing the various unexpected ways in which state and federal laws put individuals with criminal convictions at a disadvantage when trying to participate in everyday activities, including employment.

The Alaska criminal justice system touches the lives of more than 70 percent of residents, either directly or through someone they know. More than 200,000 Alaskans have a criminal record, which is close to one third of the state’s population, according to the Alaska Department of Labor and Workforce Development (DOLWD) Workforce Investment

Board. Reentry and reintegration, the path to rebuilding a life after prison with gainful employment, is often paved with obstacles such as limited job opportunities, a lack of recent skills, and the added burden of facing discrimination.

Laws are increasingly protecting applicants from discrimination based on past criminal history. "Ban the box" laws in thirty-seven states, but not Alaska, prevent employers from asking about convictions on applications, while the Fair Chance to Compete for Jobs Act of 2019 requires federal employers and federal contractors to wait until later in the hiring process to consider criminal background checks. According to the National Employment Law Project, an additional 150 cities and counties have

similar protections for both public and private sector jobs.

Unlike many states, Alaska lacks a comprehensive statute governing the use of criminal background checks in employment and licensing decisions. This means individual employers and licensing boards have greater discretion in evaluating the relevance of an applicant's criminal record to a position or profession. Consequently, professional licenses may be denied or revoked based on a conviction, but the specific criteria for such decisions may vary greatly. For instance, a criminal conviction, whether misdemeanor or felony, will not automatically disqualify or exclude someone from employment with the State of Alaska, but all convictions, even if the sentence is suspended or if the conviction has been set aside or expunged, must be disclosed at the time of application.

Reentry and reintegration, the path to rebuilding a life after prison with gainful employment, is often paved with obstacles such as limited job opportunities, a lack of recent skills, and the added burden of facing discrimination.

Organizations such as the Alaska Reentry Partnership—a collaboration of individuals, organizations, community advocates, and public entities—provide services before, during, and after incarceration—including transition support, therapeutic courts, cultural support, and employment assistance. Jonathan Pistotnik, reentry program manager for ADOC, states, “The Reentry Partnership brings together organizations and people with lived experience to use resources more efficiently and coordinate efforts across multiple organizations, better serving our big state.”

Advocating for criminal disclosure changes may be on the horizon. In 2024, Governor Mike Dunleavy formally proclaimed April “Second Chance Month.” He urged all Alaskans “to recognize the need for closure for those who have paid their debt, to commend those who have successfully reentered society, and for individuals, employers, congregations, and communities to extend second chances to former inmates.”

According to the nonprofit Jails to Jobs, there are significant advantages to hiring individuals who were formerly incarcerated, for both businesses and society as a whole. Formerly incarcerated individuals can bring much value to the workplace. They may possess transferable skills gained through work or training programs during their incarceration. A strong work ethic and dedication to start over can make them reliable and committed employees. Companies that hire formerly incarcerated individuals benefit from increased diversity and a more inclusive workplace. This can lead to improved decision-making and a stronger company culture.

Formerly incarcerated individuals can bring much value to the workplace. They may possess transferable skills gained through work or training programs during their incarceration.

A strong work ethic and dedication to start over can make them reliable and committed employees.

Additionally, such companies demonstrate a commitment to social responsibility, which can enhance their reputation in the community. Industries facing labor shortages can fill critical gaps by hiring formerly incarcerated individuals. DOLWD also provides financial incentives, in some cases, for hiring these individuals through the Work Opportunity Tax Credit program. Companies that actively hire workers who were formerly incarcerated are sometimes self-identified as “second chance employers,” and they include a variety of sizes and industries ranging from restaurants and temporary

employment agencies to professional services and manufacturers.

Indeed.com, the popular job search website, has been a champion for second chances since its beginning twenty years ago. Its very first employee, a software engineer, had a past prison sentence and internet ban. Indeed’s CEO Chris Hyams has said, "We wouldn't be where we are today if our founders hadn't been open to hiring someone who made a mistake, learned from it, and served their time.” Which may influence Indeed’s approach today of focusing on skills and qualifications first, only considering criminal records later in the hiring process, if at all. It also takes the time to understand a person’s situation—what happened, when it happened, and if it has anything to do with the job itself.

Decades of research illustrate a clear link between gainful employment and reduced recidivism, but the relationship is layered. Academic theories suggest employment strengthens social bonds, fosters a positive self-image incompatible with crime, and provides financial stability acting as deterrents. However, the quality of work matters, and employment might follow, not precede, shifts in criminal behavior.

Alaska-specific research conducted by Juneau economist Yuancie Lee, a collaboration between ADOC and DOLWD, followed 4,500 inmates who were released from an Alaska prison in 2012. The wage values in the study were nominal and include 2012 through 2015 values. All of the subjects had served time for a felony, and the study analyzed employment’s effect on recidivism over three years. In the June 2017 issue of Alaska Economic Trends , Lee published the following findings:

About half the former Alaskan inmates studied found a job at some point in the three years after their release.

• There were lower re-offend rates for those who found a job quickly.

• The rate of re-offending went down notably from 66 percent to 35 percent if they earned a higher salary (less than $12,500 versus $35,000 during the first six months after release).

• How long a job was kept mattered, with those holding a job for at least a year having a lower likelihood of returning to prison, regardless of how long it took to get hired.

• The most common first occupations after release from prison, by number employed, were construction laborers, laborers and hand movers, food prep and servers, dishwashers, cashiers, and meat, poultry, and fish cutters and trimmers.

• Few formerly incarcerated individuals find high-paying, high-skill jobs upon release (only 50 out of 4,500 reached $65,000 annually by 2015).

Lee acknowledged that other factors also play a role in recidivism, including substance abuse, mental health, poverty, extent of criminal history, demographics, and childhood abuse or neglect.

ADOC administers a unified correctional system that includes pretrial detention and secure facilities for sentenced state offenders. To promote rehabilitation and successful reintegration upon release, ADOC offers a variety of rehabilitative programs within each facility. These programs may encompass educational services like Adult Basic Education or General Education

Diploma classes, alongside vocational training opportunities.

Depending on the correctional facility, vocational programs could equip inmates with skills to earn certifications such as Alaska Food Service Worker Card, Hazardous Waste Operations and Emergency Response, or first aid/ CPR. Additionally, some programs might offer training in practical trades like motor vehicle repair, commercial driving, HVAC, or welding. This diverse range of programs aims to improve inmates' employability.

A partnership between the lieutenant governor’s office, ADOC, and the Western State Regional Council of Carpenters has launched a pilot preapprenticeship carpentry program for incarcerated Alaskans in certain facilities. The program's curriculum is focused on providing participants with the skills and knowledge necessary

Companies that support providing employment to individuals with a criminal record often cite the benefits for everyone: safer neighborhoods, stronger families, and a fairer shot at success for everyone, regardless of one’s past.

to pursue a carpentry career upon release. Successful completion may lead to union membership and industry certification.

Alaska has no federal prisons, so those awaiting trial or sentencing are held in state facilities, while sentenced prisoners are typically transferred to Federal Correctional Institution Sheridan in Oregon.

The US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) enforces Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, barring job discrimination based on race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. EEOC considers a policy discriminatory if it disproportionately impacts protected groups based on criminal history, unless the employer can justify it as job-related and necessary. EEOC enforcement guidance offers the following best practices for fair chance hiring:

• Avoid upfront inquiries: Remove the checkbox asking about criminal records from initial applications.

Transparency: Include a statement clarifying that criminal records alone won't disqualify applicants.

Train your team: Equip HR staff and hiring managers with skills to make fair decisions regarding criminal history.

• Informed consent: Obtain a signed release for background checks, covering criminal records, past employment, and education.

• Accurate information: Use reliable background check providers to ensure correct data.

Consistent application: Conduct background checks for all candidates at the same stage, ideally after the interview and not up front, to avoid potential bias.

Justice is complicated. It is layered with issues ranging from racial disparities, the connection between incarceration and health, and the role of substance abuse and its connection to crime.

ADOC Director of Health and Rehabilitation Services Travis Welch sums it up well. He states, “Our goal within corrections is for those in our custody to leave better than they came in. That can happen through a holistic approach of addressing trauma, physical health, education, and vocational training. Our hope is this leads to meaningful and gainful employment which provides a livable wage.”

Companies that support providing employment to individuals with a criminal record often cite the benefits for everyone: safer neighborhoods, stronger families, and a fairer shot at success for everyone, regardless of one’s past. But none of this can happen without businesses being open to hiring people and seeking out a wider talent pool: people who are eager to prove themselves and become valuable employees, people who are more than their worst mistake. Giving them a chance isn't just the right thing to do, it ca n be good business.

Lincoln Garrick is an assistant professor, MBA director, and alumnus at Alaska Pacific University. He has more than twenty years of experience in the business, marketing, and communications fields providing public affairs and strategy services for national and Alaska organizations.

By Tracy Barbour

elecom professionals are on the forefront of lifechanging infrastructure investments in Alaska,” says Jessica Linquist, vice president of human resources for Alaska Communications.

“With a surge of new projects, telecom work is available in our state—and it will be for the foreseeable future.”

Work is available; workers, not as much. The telecommunications industry is grappling with a talent shortage, according to the US Department of Labor. Apprenticeship programs present an effective solution for closing this talent gap. Alaska Communications and MTA are among

the providers collaborating to promote apprenticeships in the industry.

Apprenticeships offer students the opportunity to earn while they learn. Apprenticeships combine classroom learning and on-the-job training under the guidance of a journeyman. The program offers advanced training in positions including splicers, lineman, construction, installation and repair, and other field technician work. In addition, the central office has roles for network technicians.

“Over the next several years, roughly $2 billion in federal funding will bring broadband to unserved communities in rural Alaska. Alaska Communications’ partners have received more than $130 million so far to build reliable, high-speed fiber broadband in fifteen communities along the Yukon and Kuskokwim Rivers,” Linquist says.

By setting up apprenticeships, companies are preparing a workforce to install and maintain the new equipment and services.

Alaska Communications works with the Alaska Joint Electrical Apprenticeship and Training Trust (AJEATT) to train its apprentices and grow its technical workforce. The AJEATT is a partnership between the Alaska Chapter of the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA) and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 1547. The trust provides hands-on classroom and on-the-job training for a variety of electrical jobs, including telecommunications.

Meanwhile, the MTA Tech Center in Wasilla hosts AJEATT education events, which provide apprentices with unique opportunities to interact with industry leaders and gain valuable hands-on experience.

Alaska Communications apprentices Amanda Sagmoen and Jake Bates receive handson training from instructor Jeff Tanner at the NECA/IBEW 1547’s Alaska Joint Electrical Apprenticeship and Training Trust in Anchorage.

Alaska Communications

The primary goal of Alaska Communications and MTA’s public outreach campaign, Linquist says, is to increase the number of qualified candidates entering NECA/ IBEW’s AJEATT telecommunications apprenticeship program to support life-changing broadband investment in Alaska. “We want more Alaskans to consider the telecom trade and believe there is no better training opportunity than what is provided by AJEATT,” she says.

Alaska Communications and MTA are boosting the signal via traditional advertising, digital marketing, partnership promotion, community outreach/speakers’ bureau, and employee advocacy. “We’re targeting Alaskans with a particular focus on high school students, vocational students, military members, career changers, and women and minorities,” says Linquist. “There are so many benefits to working

in this trade, which many residents may not be aware of. From getting paid to go to school and not incurring any debt to the approximately $90,000 annual starting salary upon graduation, our campaign aims to communicate these benefits to encourage consideration.”

Given the state’s tight labor market, Alaska Communications is leveraging apprenticeship programs to fill its workforce planning needs for journeyman and technical positions. “Beyond journeyman roles, we’re looking to grow and retain talent in Alaska for all of our professional needs,” she says. “From finance to marketing and sales to customer service, we’re planning for the workforce we want and need in the future.”

This summer, the company hired four interns to support marketing and finance functions. “We’re engaged with the Anchorage School District’s Academies of Anchorage

program, which empowers students through career exposure, so they can make informed decisions and discover their passion while earning early college credit and industry certifications,” Linquist says.

Apprenticeship programs offer valuable opportunities for people from all backgrounds who are eager to pursue promising careers in handson trades, says MTA COO Matthew Langhoff. These programs are crucial in shaping a well-trained workforce, offering classroom and on-the-job training that prepares participants to become proficient tradespeople.

“Through these initiatives, MTA ensures that its apprentices are wellequipped to meet the demands of the telecommunications industry and seamlessly transition into fulltime roles,” he says.

Langhoff notes that MTA's apprenticeship programs have been instrumental in cultivating a highly skilled workforce, with many apprentices progressing into long-term careers there. Many employees now represent the second or third generation of their families working at MTA. “This continuity and generational commitment underscores the effectiveness of the apprenticeship programs in sustaining MTA's workforce and contributing to local community growth, particularly in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley,” he says. “Additionally, these programs play a vital role in extending MTA's capabilities by ensuring that both the company and its contractors have access to well-trained, proficient personnel.”

MTA’s partnership with the IBEW offers comprehensive telecom and power apprenticeship programs that have been integral to its workforce development for decades. For instance, MTA typically employs ten to fifteen apprentices annually, immersing them in real-world operations from the start. These programs are designed to develop essential technical skills while instilling a deep understanding of MTA's standards, expectations, and company culture.

The apprenticeship programs cover a range of critical roles: install and repair technicians; line crew members and cable splicers; and tower, wireless, fiber optic, and broadband network technicians. These roles are essential for both outside and inside plant operations.

MTA has also adjusted its scholarship offerings to support individuals pursuing certifications and trade qualifications, extending eligibility beyond recent high school graduates to include individuals who may have new career goals. “Emphasizing the value of a skilled trade, combined

with the promise of a stable and rewarding career, is key to attracting more young professionals to the industry,” Langhoff says.

The AJEATT offers training in various electrical industry job classifications, including inside wireman, residential wireman, outside power lineman, and telecommunications worker (telephone/data). The classes are primarily held at its electrical training centers in Anchorage and Fairbanks, which together host about 100 telecom apprentices.

At the Tom Cashen Training Center in Anchorage, the apprenticeship program entails 840 hours of classroom instruction (divided into three sessions) and 8,000 hours of on-the-job training with a journeyman. “The classroom training is a mix of actual bookwork and skills labs created by our highly qualified instructors,” says AJEATT Statewide Training Director Melissa Caress. “All of

the lessons are backed up by hands-on training in a controlled environment. It typically takes four to four and a half years, depending on the hours worked.”

The program offers specialized tracks, so participants can choose from several journeyman classifications. Apprentices can test in four areas upon program completion: CO/PBX (phone systems), install and repair technician, telephone lineman, and fiber splicer. Caress explains, “During their apprenticeship, they are educated on all aspects; however, the last period of their enrollment is focused on the trade they are planning on pursuing as a journeyman.”

Apprentices gain the practical knowledge to perform tasks related to the different occupations during their classroom instruction, as well as hands-on training in the field under the supervision of a journeyman. This enables them to get a well-rounded education and complete the program ready to train the next generation of apprentices. “The hands-on learning

model, both in the classroom and in the field, prepares them to become competent workers and face the challenges in the industry that are presented to them,” Caress says.

During classroom training sessions, apprentices must complete multiple competency tasks, including rigorous safety training. For example, apprentices are required to complete and pass bucket truck rescue and pole-top rescue, learn how to operate heavy equipment, and safely climb and perform tasks at realistic heights. “Our model during classroom training is to imitate real-world situations faced in the field,” Caress says. “We have a myriad of labs that explain not only the ‘why’ behind what they’re doing but also the ‘how’ in order to send out a prepared individual.”

Casey Ptacek, training coordinator at the AJEATT’s Kornfeind Training Center in Fairbanks, follows a similar approach. To ensure apprentices are well prepared for challenging work conditions and environments, they are

placed in the field with experienced and knowledgeable journeymen. “We also limit the number of apprentices a journeyman can oversee to ensure they can keep a watchful eye,” he says.

Safety, Ptacek says, is the apprenticeship program’s top priority— always. Every apprentice receives comprehensive training in a host of areas, including fiber and copper splicing, pole climbing, confined space, cable lashing, networking, protocols, cabling, heavy equipment operating, structured cabling systems, test sets, troubleshooting, cable locating, bonding and grounding, tower construction/climbing. “We are the only place in the state of Alaska to receive globally recognized BICSI [Building Industry Consulting Service International] certifications, along with the other OSHA 10 [safety course], rigging, mobile crane/Digger Derrick, FOA [fiber optic association], CPR, and pole-top rescue certifications,” he says. Ptacek adds, “Telecommunications is an ever-changing, vast industry with

many specialties and skills required to get the job done from start to finish. The IBEW 1547 AJEATT is the most robust training program in the industry, turning out (journeying out) the highest-trained techs in the field.”

The AJEATT also conducts multiple, two-day introductory courses for high school students at the Fairbanks Pipeline Training Center, where participants receive a two-day crash course in electricity. “We also teach an 80-hour Intro to Electrical trades course at the Fairbanks Pipeline Training Center for high school seniors and juniors the week after school ends,” Ptacek says. “Graduates of this course receive a completion certificate and are eligible for a direct interview.”

Caress urges telecom companies to be intentional about using apprenticeship to accelerate employee development. “As the work demand continues to increase, it is important to utilize apprenticeship to its fullest capabilities,” she says. “The Department of Labor allows one apprentice per journey worker to be trained in the field. We face success in meeting workforce needs by using apprentices at this rate.”

To simplify the path to apprenticeship, there’s Alaska Works. The nonprofit runs a free pre-apprenticeship program that provides introductory, handson workshops to help people better understand the telecom industry and assist with the application process for NECA/IBEW’s telecom apprenticeship program. Additionally, Alaska Works also provides apprenticeship opportunities through its Women in Trades and Helmets to Hardhats (for military veterans) trainings.

The telecom pre-apprenticeship program—which receives grants from the US Department of Labor—spans

three eight-hour days. It’s held during daytime, evening, and weekend sessions to accommodate various schedules.

Last year, Alaska Works received more than 100 applications for the program, according to Outreach Coordinator Nicole Pennie. “Everybody qualifies for our training, and no prior experience is required,” she says.

Program participants—about 30 percent of whom are 18 to 24 years old—get a chance to learn technical skills like cable splicing, installation, repair, and testing, as well as hone their soft skills. This enables them to explore the telecom industry and ask questions before committing to a career. Pennie explains, “We allow them to pursue a curiosity before going into a job. They get hands-on skills to put on their résumé. They receive a certificate of completion for the program. And if they

were really good in their class, we have Top 5, and our instructors can write them recommendation letters.”

Aspiring telecom apprentices need to be curious, ask questions, and show up on time, Pennie advises. She says, “People sometimes get nervous and don’t want to try things. They say, ‘I don’t have the experience.’ You can learn hard skills, but you need to bring the soft skills. However, there is training and instruction available that can help them grow their skills.”

Pennie encourages both men and women to consider telecommunications apprenticeship as a pathway to a promising career. “Everybody knows about the billions of dollars coming to Alaska, so there’s no better time to get into the telecom field,” she says. “This is a lifelong career that we can help them start.”

From its humble beginnings as a horseand-cart operation delivering materials and goods to mining camps almost eight decades ago to its current iteration as a fully integrated, inter-modal, interstate marine freight common carrier, Samson Tug and Barge has always prided itself on being “Alaskans serving Alaskans.”

“We’re family owned, and we treat each other and our customers like family,” says Vice President Cory Baggen of the company started in 1937 and still run by her father, George Baggen. “Our success has come from looking out for our friends and neighbors.”

These close relationships include those with long-term vendors like GCI. For more than twenty years, GCI has helped the business grow, providing internet, cellular, and landline service at the majority of Samson’s locations. Samson offers barge freight and cargo hauling services on a scheduled, yearround basis from and throughout Alaska, as well as interport connections and charter and seasonal services.

“Any place that has GCI available, we use it,” says Baggen.

She notes that GCI has gone above and beyond when needed, including when Samson was a victim of a cyberattack eight years ago. “It shut us down and I didn’t know what to do,” says Baggen, who had no computers or servers at her disposal to track and ship freight. “GCI

By Vanessa Orr

called in the calvary, and their team got us up and running in days—sometimes working until 2 a.m. To be quite honest, without them, I don’t know if we’d still be in business.”

“They have always responded when we’ve called,” adds Annika Hansen, director of information systems. “Our new account manager, Andrea, even called us recently to let us know that we would be getting reimbursed for the services we couldn’t use when a cable was cut in Sitka. I hadn’t even contacted her about it, but she wanted us to know that they were going to take care of us.”

“We’re really thankful for their service,” adds Baggen. “We’re big GCI fans.”

Headquartered in Alaska, GCI provides data, mobile, video, voice, and managed services to consumer, business, government, and carrier customers throughout Alaska, serving more than 200 communities. The company has invested more than $4 billion in its Alaska network and facilities over the past 40 years and recently launched true standards-based 5G NR service in Anchorage. GCI is a wholly owned subsidiary of Liberty Broadband Corporation. To learn more about GCI and its services, visit www.gci.com.

By Dan Kreilkamp

n July, the Alaska Trucking Association (ATA) welcomed Jamie Benson as its new president and CEO. The transportation industry veteran was a natural fit, having climbed the executive ranks of FedEx. She previously served as ATA’s board president in 2019.

Benson says Alaska has always been home—something she credits largely to her father’s adventurous spirit. “He was a native Hawaiian and served in the Navy, but he always wanted to be that Alaska wild man, so that’s how we ended up here,” she says with a laugh.

A frank conversation with Benson’s father also proved to be a driving force behind what’s been an illustrious, thirty-year career in logistics, strategic planning, and business management.

After graduating from Chugiak High School and attending UAA in pursuit of a fine arts degree, Benson pivoted to a career with FedEx. “I started out as a handler, was a forklift

driver, and for the first ten years I kind of bounced around, finding my way through different leadership roles,” she reflects. “And for the next twenty years, I assumed different management roles, and that’s actually where I got my first exposure to the ATA.”

As she gears up for this latest challenge, Benson set aside some time to chat with Alaska Business to lay out her vision for the future of the organization and the trucking industry at large.

Alaska Business: What drew you to this position with the ATA?

Benson: I served on the board for many years, and I was actually the board president in 2019. I originally joined the ATA because I managed drivers on road operations; I had a vested interest in protecting my

drivers and making sure that they were exposed to all sorts of safety training and opportunities with truck driving championships. So that's how I first became affiliated with the ATA. And I always had my employees’ best interest at the forefront. My motto for leadership was always: take care of your employees and they'll take care of you. So that's how I managed at FedEx, and when the opportunity to lead the ATA came about, I knew that I could bring that same leadership, that employee-focused mentality to the organization.

AB: What are the primary objectives of ATA, and what services do you provide your members?

Benson: The two primary objectives are support and advocacy for the industry. Our membership is made up of trucking-related positions,

ATA is actively trying to remove the stigma of truck driving. I think for a lot of folks—especially our younger workforce—it doesn't sound like a viable option.

drivers being the majority, but we also provide safety-focused training, which is led by our safety management committee. Recently, we partnered with Wrightway Auto Carriers, and they hosted a pipe tie-down demonstration and highlighted best safety practices and awareness. We have two DOT inspection classes coming up to educate drivers on what to expect if their vehicles are chosen for inspections. This helps the companies by reducing their violations.

We host CPR training classes and leadership training—I'm actively working on putting together an interview skills class for anyone who wants to promote within the industry, because I always felt that was my niche at FedEx. It took a long time to cultivate that skill, but I learned over the years—by interviewing myself and also interviewing hundreds of employees—what

an employer is looking for and to make that time valuable for the employee and the employer.

ATA’s incredible staff also provides commercial and personal DMV services to our members and the public. I would say one of our greatest services that we provide here is networking and collaboration opportunities for our members, building that network so that they can find resources within their own industries. Those are the types of support services that we provide.

The other big thing is advocacy: we are all about advocating for our membership. We're actively working to influence transportation policies at the state and the federal levels, and we want to ensure a favorable business environment for our members.

AB: What has been one of the highlights of your tenure with ATA to date?

Benson: I recently had an opportunity to ride along the Dalton Highway— the “haul road”—with three of our carriers. This experience was invaluable to me. The challenges facing our drivers on a daily basis cannot be overlooked. The Dalton is probably the hardest road to travel in the country, and our drivers are braving it every day to provide necessary goods and equipment to support the oil and gas industry. Their skills and professionalism play a vital role in ensuring a reliable transportation network. This experience truly amplified my respect and admiration for all of our drivers here in Alaska.

AB: What is your vision for the future of the organization?

Benson: The trucking industry has changed over the many years that we've had vehicles on the road. But I think overall our membership is so

wonderfully diverse with a wealth of knowledge and experience. We have a board of twenty-one members, and they're an amazing group of industry leaders: executives, frontline operators, sales. And every one of those members has a reason for belonging and contributing to the ATA. But it's my vision and my goal to bring all of those voices together in a manner that strengthens the collective voice of the ATA. We want to foster innovation and collaboration and drive progress in this ever-changing environment. So my vision is to take this organization of 200-plus members and find a collective voice so that we all reach our goals.

AB: How are changes in shipping and logistics, such as the new Amazon hub in Anchorage, affecting the industry?

Benson: Even when I was with FedEx, I loved that Amazon had a place in Alaska. You saw the introduction of Amazon and their warehouses. And I never really saw them as a threat because of the way our industry is now and that need for instant gratification of delivery. There's more than enough business out there for all of the trucking companies.

And when you mention Amazon, FedEx, UPS, USPS—they're not instantly recognized as trucking companies, but they are: they provide a service through a vehicle. But I would definitely say our old saying of “If you got it, a truck brought it” still rings true, now more than ever. Your first thought about the trucking industry is the big tractor trailers, but the small package delivery system—they're just as integral. And they're driving vehicles. They're driving trucks. So that last leg of a very intricate supply chain movement is critical.

AB: A lack of licensed drivers is obviously one of the challenges that Alaska and Outside companies are trying

to address. What do you see as the root of this problem, and what is your organization doing to help attract more people to this career?

Benson: ATA is actively trying to remove the stigma of truck driving. I think for a lot of folks—especially our younger workforce—it doesn't sound like a viable option. Removing the stigma of truck driving as just being a long-haul driver is what's going to be critical to our industry to bring more people into this career.

There's a myriad of support roles in the trucking industry: administrative, executive, maintenance. So we're going to career fairs, and our stance is that a four-year degree is great if you're focused enough and that's where you want to go and a four-year degree is required. But that's not necessarily what's needed to have a fulfilling life and a long-term career.

I've told this story a hundred times over because I'm actually very proud of it: my son, with my affiliation with the ATA, he was really exposed at a young age to this industry. His father is an aircraft mechanic, so he's mechanically inclined, but he wasn't the best student. Academics wasn't his forte, so we always knew that wasn't a path for him. I was able to promote trade to him as an option for a career. So he's been trained as a diesel mechanic, and now he works for one of our members.

AB: What other efforts is ATA making to remove the stigma from the trucking industry?

Benson: I really believe that exposure is going to make the impact: building partnerships with UAA and ASD [Anchorage School District] and introducing the trucking industry in

Commercial truck drivers are more than steady hands on the steering wheel. They are trained to check vehicles daily for any sign of defects.

ways that don't immediately come to mind. Just because you're good at accounting doesn’t mean you have to go and work for a big company downtown; the possibilities are endless in the trucking industry. It's just about finding the right venue for that. But for us right now, we're working on apprenticeships within our industry, and there's a maintenance apprenticeship program at Alaska Central Express that's been really successful. But creating that pathway within the industry is going to help us as well. It’s all about introducing the possibilities early on and fostering them in-house.

AB: What do you think are the other biggest challenges facing this industry?

Benson: Right now, the biggest challenge for our industry is infrastructure. As soon as I came

You've got bears coming out of nowhere, moose, people breaking down on the sides of roads, and so you have an inherently human factor and emotional intelligence that I do not think that self-driving vehicles can support for Alaska driving conditions.

on board, the first issue that I was introduced to was the Dalton Highway and opportunities on the haul road. There's a significant amount of regulatory bureaucracy that goes on there and funding that needs to be pursued. But in my mind, a basic need for safe driving and safe transport are safe and maintained roads. So we're actively working with other associations to draw attention to the plight.

The Dalton Highway is kind of "out of sight, out of mind." If you have a giant pothole on Minnesota [Drive] and Benson [Boulevard, in Midtown Anchorage], you've got 20,000 people going onto social media, posting videos, and drawing attention to it. With the Dalton Highway being so, like I said, out of sight and out of mind, it’s not getting the attention that it needs. So that's something that we are actively working towards.

AB: What are your thoughts on selfdriving or automated tech and how that might impact the industry?

Benson: I think self-driving and automated tech makes a lot of sense for the Lower 48 where you have longer stretches with less impact from environmental concerns. Alaska is wild, and I don't think that our infrastructure lends itself to self-driving vehicles. At least not right now. Like I said before that, I don't think the infrastructure is the re to support that.

When I was with FedEx, we implemented a lot of systems in our vehicles so they're very selfaware. These webcams that are in truck cabs can tell when you're blinking, if you look like you're tired. There’s all these systems that the vehicles have for driver awareness and health and safety.

But you cannot discount the human factor for the Alaska environment. We had, what, 130 inches of snow last year? You're telling me that a self-driving vehicle will be able to navigate that safely or make decisions based on the safe driving conditions of the road? If that were true! [she laughs] You've got bears coming out of nowhere, moose, people breaking down on the sides of roads, and so you have an inherently human factor and emotional intelligence that I do not think that self-driving vehicles can support for Alaska driving conditions.

AB: If you could deliver one message to our readers, what would that be?

Benson: My message for the readers is that the trucking industry—especially in Alaska—is vital. It's not going anywhere. We have freight handlers, executives, admins, dispatchers, maintenance teams, professional drivers—they're always going to be vital to keeping our community and our economy moving. With the industry, you transport goods across the country in partnership with air and sea transport, and we are ensuring that you have these essential items reaching stores, businesses, your home. The members of this industry, this community, they're the reason that we can live the lives th at we do in Alaska.

I mean, we have a reputation for being wild. We're distant. But there is a great benefit to living in Alaska…. We have everything that we need at our fingertips, but it is because of the trucking industry, the [Alaska] Marine Highway [System], and the air transport network. The trucking industry is an integral part of what makes it possible for us all to live here in this beautiful state.

Th is section glimpses the future of AI technology insinuating itself into oil and gas exploration and production. Dig into the companies eyeing nickel and graphite deposits to drive forward the energy transition. Baseball cards serve as an aid for understanding Alaska's major producing mines, and peek over the border to seek how mining in Canada affects fishery res ources in Southeast.

The forests of Southeast, heaving with wood resources, are poised for new development thanks to legislation promoting local lumber grading. Forests are also treasured by cruise ship visitors, which is why tourism counts as a natural reso urce industry too.

By Rindi White

Machines capable of learning are the forerunners of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as far beyond the vacuumtube computers that heralded the Third Industrial Revolution as those contraptions were to the telegraph that wired together the Second.

The changes that have already come are revolutionary; the changes on the horizon are even more so, says Helena Wisniewski, UAA professor of entrepreneurship and chair of its

management, marketing, logistics, and business analytics department. She’s also the university’s first Marion Porter chair, an endowed chair within the College of Business and Public Policy.

Wisniewski spoke recently at the Alaska Oil and Gas Association Conference on the topic of AI in the oil and gas industry.

“We are currently in the era of Generative AI. Generative AI is a subset of Narrow AI, which is specific tasks. Generative can create and design, and

it uses natural language processing and deep neural networks to do that,” Wisniewski told the audience. “But we’re moving toward general AI. That’s where all the science fiction data comes in. General AI will have cognitive ability, understanding, decision making, and maybe reasoning—but we’re not there yet. Experts debate whether it will be in three to five years.”

What AI is currently capable of—and how it will change in the coming years— is something every industry should

be looking at, Wisniewski says. Oil and gas companies are already tapping into some of the potential AI brings with it, and the industry is poised to expand its use even more.

Several oil and gas companies are using “digital twins” to bridge the physical and digital world. A digital twin is a virtual representation of a real-world entity, such as a prototype product or a factory floor, which uses real-time and historical data to capture how the entity works, uses sensors to understand how it’s currently working, and uses AI to predict how it might work in the future. They’ve been in use since about 2002.

If, for example, a widget factory creates a digital twin of the equipment, it would be possible to use a digital twin system to test (without much capital investment) how an upgraded logic control system might integrate with existing equipment and affect performance of existing machines, as well as the quality and amount of widgets that would be produced as a result of the upgrade.

At least one digital twin system is already in use in Alaska. Clay Koplin, CEO of Cordova Electric Cooperative (CEC), says his utility has an “extremely sophisticated” control system built up over the past twenty-five years. The cooperative hosted, in partnership with the US Department of Energy, the largest grid modernization project in the United States, Koplin says. As part of that modernization plan, CEC built a digital twin of its grid. It’s hosted at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory Advanced Research on Integrated Energy Systems campus in Golden, Colorado.

When a federal client asked CEC if it would be possible to extend power to

a location 27 miles from the existing CEC power grid, an independent engineering firm used the digital twin to model and analyze whether the proposal would be economically feasible. The contractor was able to adjust parameters, tweaking it this way and that, and finally found a way to make the project feasible, Koplin says. Now the client is analyzing whether to move forward.

Oil company bp is using digital twin technology to monitor its new Azeri Central East (ACE) platform in the Caspian Sea.

“We call it a one-stop shop, where you can get all the information about ACE and its insides that anyone could need,” says Yekaterina Novruzlu, senior instrument and controls engineer for the ACE project in an article on

When the unexpected happens in Alaska’s toughest conditions, LifeMed Alaska is your partner in emergency care. Our corporate emergency membership ensures your team is protected with rapid, life-saving medevac services, wherever the job takes them.

From the rugged terrain of Alaska’s oil fields to the remote reaches of the wilderness, we are ready when you need us. Protect your most valuable assets, your people.

Get your corporate emergency membership today. Visit LifeMedAlaska.com or call 1-855-907-5433.

“Energy companies should consider adopting that ‘coopetition’ mindset: in certain areas, it’s in our interest to cooperate for the good of society, whereas in other areas, competition is needed to drive innovation forward.”

Dan Jeavons Vice President of Computational Science an d Digital Innovation Shell

bp’s website. “Let’s say there was a maintenance issue with a part that is not readily accessible. In the past, it might have meant sending someone offshore, setting up scaffolding, and taking photos as a first step. The digital twin allows us to understand what is involved and then decide on a course of action in just a few minutes or hours.”

ACE is one of seven offshore bp platforms feeding into the Sangachal terminal, one of the world’s largest oil and gas terminals, near Baku, the capital city of Azerbaijan. After engineering out, as much as possible, single points of failure on the platform, bp engineers are analyzing the digital twin for ways to increase safety and efficiency, says Ruhali Imanov, the commissioning superintendent of the ACE platform.

“We also looked at how, while maintaining and prioritizing safety, we could build in more time between maintenance shutdowns, known as turnarounds, when production has to be reduced or stopped,” Imanov adds. “The intention with ACE was that it would act as a pilot design for the platform of the future. When we started talking about this kind of automatization back in 2018, it seemed like we had a nearimpossible task ahead of us. This start-up is a real milestone after years of conceptualizing, engineering, planning, and execution.”

Digital twins are not artificial intelligence, per se, but they are a model that can, when combined with AI, provide continuous learning, predict performance, and elevate predictive maintenance to a realtime strategy to more accurately anticipate and prevent failures, resulting in greater efficiency, safety, and reduced costs. Digital twins are

being used not just to fix issues but predict them before they even happen, Wisniewski says. She enrolled UAA to be a member of the Digital Twins Consortium, which aims to accelerate the market by fostering development, increasing adoption, and improving the interoperability of digital engineering projects propelled by digital twins.

Shell has been an early adopter of AI, dating as far back as 2013. In 2021, it announced a partnership with oil field services company Baker Hughes and technology companies C3 AI and Microsoft to create and offer for widespread use the Open AI Energy Initiative (OAI). Dan Jeavons, Shell’s vice president of computational science and digital innovation, says it’s akin to the Apple App Store but for the process industry.

“Digital technology is a key enabler to facilitate the way we are doing business. As an energy company, we have to adapt to remain at the forefront of this transformation. The three previous industrial revolutions have demonstrated that not only the most advanced industries were successful, but the ones that were able to partner, develop, and work together effectively were the ones that often stood out,” says Christophe Vaessen, Shell’s general manager, commercial for its European Union, Middle East and Africa region, in an interview on Shell’s website. “Today, by bringing this OAI platform to life, we are building an open environment that enables all parties to work together toward a common ambition. The OAI is an open platform where companies can plug in and commercialize their apps. This includes not only international oil companies but also different sectors,

such as cement or mining companies, that are running large operations and looking for digital tools to help with predictive maintenance.”

This way, similar user types aren’t having to reinvent the wheel, so to speak. The goal, Vaessen says, is to reduce integration and operating costs for users of the platform and to boost digital transformation in the heavy industrial sectors.

“The amount of time we all spend building our own proprietary platforms is truly remarkable. Working towards an integrated system is absolutely the idea behind the OAI. Now, the big challenge is that it will only work if you get adoption. So you can’t do this alone. And that’s why the fair value exchange is so important because it can’t be about one person gaining competitive advantage over the others. It has to be an ecosystem play,” Jeavons says. “Tech companies have done a very good job of what is commonly referred to as ‘coopetition.’ In many areas they cooperate, and in many areas they compete, and they’re able to do so simultaneously. Energy companies should consider adopting that coopetition mindset: in certain areas, it’s in our interest to cooperate for the good of society, whereas in other areas, competition is needed to drive innovation forward.”

In late 2021, Shell announced three new applications on the OAI platform: a process optimizer that “marries stateof-the-art LNG [liquified natural gas] process engineering and technology with data analytics” to optimize production; a corrosion advanced-risk modeling and analytics application that predicts internal corrosion and erosion to better pinpoint maintenance activities; and an autonomous integrity recognition app that processes data in the cloud coming from inspections

made by handheld devices, drones, and robots to help inspectors evaluate issues and identify items that might have been overlooked, improving maintenance planning.

The initiative welcomed a cohort of new partners in 2022 and, in the same year, announced it had scaled its predictive maintenance program, driven by AI, to include more than 10,000 pieces of equipment across its

global asset base, one of the largest deployments in the energy industry. According to Shell, the underlying technical infrastructure monitoring those pieces of equipment take in 20 billion rows of data each week, from more than 3 million sensors. It also trains, tunes, and runs nearly 11,000 machine learning models in production and makes more than 15 million p redictions each day.

“AI is a huge opportunity for us. We’re going through a digital transformation, firstly to make ourselves more effective and efficient, and secondly to make sure we thrive through the energy transition.”

Dan Jeavons

Vice President of Computational Science an d Digital Innovation Shell

The measures are directly linked to cost savings and greater efficiency.

In a 2021 Bloomberg article, Shell reported its digital program delivered $1 billion in cost savings in 2019 and $2 billion in 2020. It also reported a 25 percent time savings in work processes by using AI to better understand the subsurface and maximize recovery from existing oil and gas fields.

“AI is a huge opportunity for us. We’re going through a digital transformation, firstly to make ourselves more effective and efficient, and secondly to make sure we thrive through the energy transition,” Jeavons said in the Bloomberg article. “There’s huge disruption in the energy market, and as we go through this and move toward cleaner energy solutions, Shell wants to lead the way, and AI plays a huge role in that.”