9 minute read

CHARLES CHRISTIAN GEORGESON FATHER OF ALASKAN AGRICULTURE

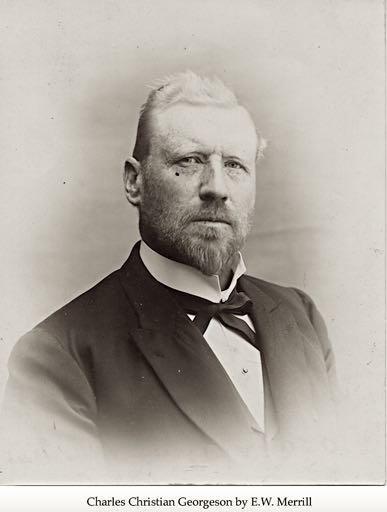

Charles Christian Georgeson

Advertisement

Charles Christian Georgeson

[Photographer E.W. Merrill

In the early summer of 1900 Dr. Charles C. Georgeson and an associate made a trip from Seattle to the interior of Alaska. Dr. Georgeson detailed the journey in his Fourth Report on the Agricultural Investigations in Alaska, 1900, published by the Government Printing Office in Washington, D.C., in 1901. The chapter titled “Investigations in the Interior” is an interesting look at the transportation routes and modes of the time, and is available to read online at the Internet Archive (see Resources, page 48). The importance of that trip is underscored in the Introduction by Dr. A. C. True, Director of the Office of Experimental Stations, U.S. Department of Agriculture:

“One of the most important features of the work of the year was the prelimiary survey of the interior of Alaska and the location of experiment station tracts at Rampart and Fort Yukon in the valley of the Yukon River. Professory Georgeson and Mr. Jones traversed the Yukon country, starting from Dawson July 6, 1900, visiting all the more important villages along the river, investigating their possibilities as agricultural centers. As a result two tracts of land were surveyed and requested. They consist of 100 acres at Fort Yukon and 313 acres at Rampart. These places seem to be best adapted to further investigations, and whatever results are achieved at these points will apply to most of the interior region.”

Dr. True also observed that “….some advance has been made toward completing the station headquarters at Sitka, and work was begun upon the station building at Kenai, but the sum available for this purpose was so small that little was accomplished.”

It was noted that “the services of a skilled horiculturalist were needed at the Sitka station to aid in the introduction of new and valuable fruits,” and “it is thought desirable to begin investigations in dairying, and for the foundation of the herd animals will have to be purchased. These and other comtemplated improvements mentioned in the accompanying report will necessitate a larger appropriation than has hitherto been given.”

Dr. True requested an appropriation of approximately $15,000 to cover the operations of the entire fiscal year of 1902, and to fortify his observations and recommendations he explained, “Conditions in Alaska are very similar to those of Finland, where there is a population of 2,500,000 and where 34,000,000 bushels of cereals are raised annually. In 1895 there were in Finland 4,000,000 head of horses, cattle, sheep and swine, and dairy products to the amount of $6,750,000 were exported. The special agent in charge of the Alaskan investigations believes Alaska is as good a field for agriculture as Finland if the proper encouragement be given it.”

That special agent was Dr. Charles C. Georgeson, and he would spend 30 years promoting and supporting the agricultural development of Alaska. In an article for Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Oct., 1978, James R. Shortridge, then associate professor at the University of Kansas, wrote in an article titled ‘The Alaskan Agricultural Empire, An Agrarian Vision, 1898-1929:’ “Today it is easy to scoff at the general optimism that pervaded Alaska following the discovery of gold in the Klondike. Contemporary publications that championed ‘the role of the cow and the plow in interior Alaska’ or pronounced the region ‘a land of illimitable cereal and stock raising capabilities’ now look very foolish to us. But the hopes for Alaska’s agricultural future, when examined in the context of their time, seem not only rational but perhaps attainable.”

No one believed in that attainability more fervently than Charles Christian Georgeson, born June 26th, 1851, on the island of Langeland, Denmark. In 1867, at the age of 16, he began serving a five year apprenticeship in horticulture. He emigrated to America in 1873, graduated from Michigan Agricultural College in 1878 with a Bachelor of Science, and received a Master of Science degree from the same institution in 1882, at the age of 21, already having gained a widespread reputation as an outstanding plant breeder and agronomist. After graduation Dr. Georgeson spent several years teaching in Texas and Japan. Upon his return to the U.S. he was appointed Professor of Agriculture and Superintendent of the farm at the Kansas State Agricultural College, and over the next few years he met many of the men who would eventually join him in Alaska to lead the various experiment stations. A year after the Hatch Act of 1887 authorized agricultural experiment stations in the U.S. and its territories to provide science-based research information to farmers, the secretary of agriculture appointed Dr. C. C. Georgeson the Special Agent in Charge of the U. S. agricultural experiment stations, and sent him to Alaska. He was 47, with a wife and three children.

A brief biographical sketch at the University of Alaska website notes, “Because Alaska's agricultural potential was unknown, Georgeson was limited only by budget and enthusiasm; he'd been instructed by the Secretary of Agriculture to "Act as if the country is your own and go ahead: Washington, D. C. is a long way from Alaska and all I want are results.”

The first two agricultural experiment stations were at Kodiak and Sitka, which would eventually become the headquarters station and Georgeson’s home. At first Dr. Georgeson rented a small house for his office at Sitka. Governor J. G. Brady offered his own barn to house the station’s oxen for the winter of 1898-1899, and in an interview for Sunset magazine in 1928, Dr. Georgeson explained how he borrowed patches of land from the settlers around Sitka until he could clear and drain enough land to plant crops for the experiment station: “My plots were scattered all over the village and having insecure fences, or no fences at all, the local boys, cows, pigs and tame rabbits rollicked joyously through them. Hens, which in Sitka fly like seagulls, flocked to the feast I had unwittingly prepared for them, and when, by chance, they overlooked anything, the seeds came up to become the playthings of diabolical ravens, who, with almost human malice, pulled up the little plants merely to inspect their other ends.”

But Dr. Georgeson set about the considerable task before him with an energy and optimism which would carry him to many successes. He generously shared what he learned with those coming after him, writing 47 books, pamphlets, and circulars about the state and its agricultural potential, and articles for popular magazines like National Geographic. In a 1902 bulletin, Suggestions for Pioneer Farmers in Alaska, he wrote, “…Hardy vegetables have been grown with marked success almost everywhere in Alaska where they have been tried, and likewise, early maturing grains have been grown successfully in many places. Potatoes, cauliflower, cabbage, kale, peas, lettuce, turnips, rutabagas, and radishes have been grown at nearly every white settlement in the coast region and in many places in the interior.”

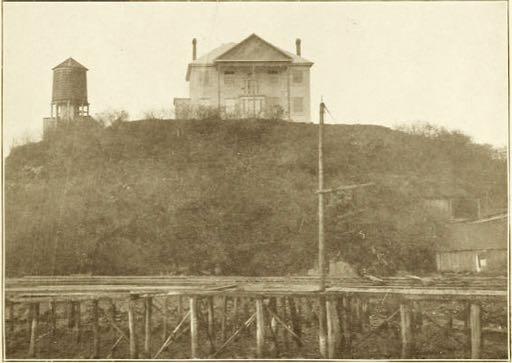

Sitka Experiment Station, Dr. Georgeson’s home and headquarters on Castle Hill, 1899.

[Photo from Dr. A. C. True’s book, The Agricultural Experiment Stations in the United States, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1900]

In 1903 Dr. Georgeson explained why Sitka was selected as the headquarters site: “The reasons for locating the headquarters in Sitka were accessibility and climate. It was deemed necessary to locate this station at a point which could at the same time be in a reasonably easy communication with the rest of the Territory. Sitka was deemed to be that point. At that time there was no indication of a speedy opening of the interior. The coast region contained practically the whole population and it seemed likely to remain the most important region for a long time to come.”—C.C. Georgeson, Special Agent In Charge, Alaska Agricultural Experiment Station, Sitka, 1903.

The Kodiak station, also established in 1898, operated until 1931. Stations in Kenai (1899–1908), Rampart (1900–1925), Copper Center (1903–1908), and Fairbanks (1906–present) followed quickly. In 1915 the final station, at Matanuska, was established and is still operating. The agricultural research done at these stations over the years developed numerous northern-adapted varieties of grasses, grains, vegetables, and berries, as well as the adoption of desirable crop varieties from around the circumpolar north. Dr. Georgeson carried on numerous cross-breeding experiments, including one which resulted in the hardy Sitka hybrid strawberry, developed by Georgeson in 1905 by pairing a wild beach strawberry from Yakutat with a commercial variety.

Harvest from the garden of Governor John G. Brady at Sitka, at ”Old castle Sitka.”

[by Elbridge W. Merrill. From ‘Suggestions for Pioneer Farmers in Alaska,’ by C. C. Georgeson 1902]

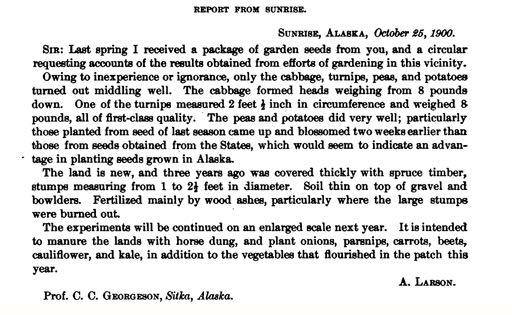

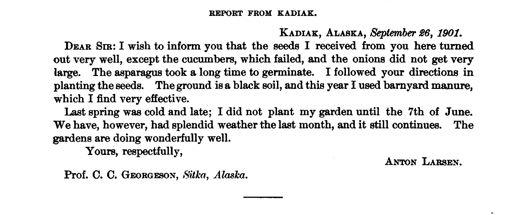

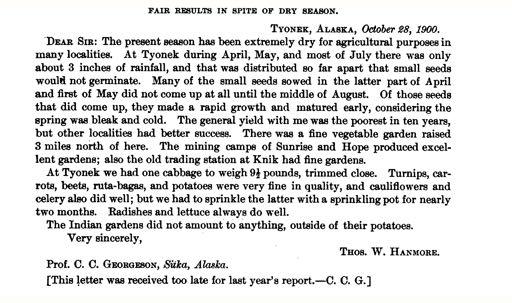

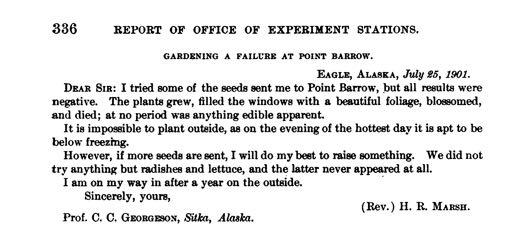

Sample field reports received by Dr. Georgeson, from his 1901 Report of Alaska Experiment Stations:

Another example of Georgeson’s experimental work can be seen in his report on utilizing seaweed to fertilize potatoes, a practice still used in coastal areas. Georgeson wrote in 1901, “Although the crop was but light and can scarcely be called a success, the experiment is nevertheless of interest, because it shows that seaweed, so abundant everywhere along the coast, is an excellent fertilizer for potatoes.”

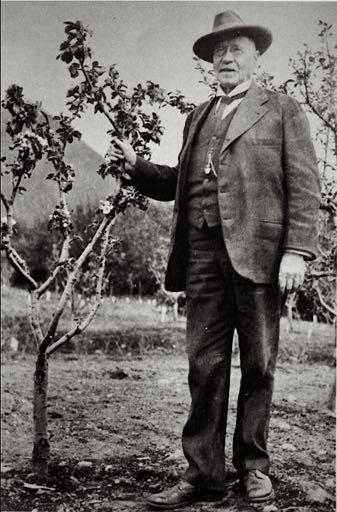

A different function of the Sitka Station was the propagation and distribution of nursery stock to early Alaskans, given in exchange for season-end reports on the results. The 1928 Alaska Agricultural Experiment Station annual report recorded that nursery stock was sent from the Sitka Station to 170 residents of Alaska, including strawberry, raspberry, gooseberry, and currant plants, apple trees, rhubarb plants, ornamental shrubs, and seed potatoes.

Strawberry plants on government farm at Sitka, 1916.

[photo by Curtis & Miller, Library of Congress, Carpenter Collection, LOT 11453-1]

Dr. C.C. Georgeson standing with a young apple tree at the Sitka station.

In 1931 the federal government transferred ownership of the four remaining experiment station facilities—at Sitka, Kodiak, Fairbanks and Matanuska —to the College of Agriculture and Mines in Fairbanks, which was renamed the University of Alaska in 1935. Deemed unnecessary, the Sitka and Kodiak stations were closed.

A good history of Prof. Georgeson and the Alaskan agricultural experiment stations can be found in a series of articles for Agriborealis, published by the Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station, University of Alaska Fairbanks in Spring, 1998 (see Resources, page 48). Two excerpts:

“The research efforts received popular approval. ‘You can imagine my joy when many branches set fruit. Everyone in the village was advised of the experiment and warned against disturbing those bushes. Then just about the time the fruit was ripe, the Indian women came along and gathered every one of my apples and made them into jelly!’”

“Most of the original 110 acres of the Sitka station has reverted to a second growth spruce-hemlock forest interspersed with muskeg. The house where Georgeson lived and worked, the station’s horticulturist cottage, and a root cellar remain in use today. About 20 fruit trees, some berry shrubs, strawberries, and ornamental trees and shrubs are all living reminders of the role this site played in the development of agriculture and horticulture in Alaska.” ~•~