17 minute read

PIONEERING FARMERS IN THE MATANUSKA VALLEY

Knik Garden, 1900. [Photo credit: University of Alaska, Fairbanks]

Providing food for the early gold and coal miners spurred the clearing and planting of the first gardens and farms in south-central Alaska’s Matanuska Valley. By 1906, farmers Henry McKinnon and Hiram Mitchell were both producing large gardens near Knik, and the sales of their produce to the local villagers and miners in the Willow Gold District were the first recorded. Among other firsts in the Valley were Captain Axel Olson’s introduction of three Holstein cattle and one Jersey cow in 1914; W. J. Jeff Bogard’s first flock of sheep; and John Bugge, a homesteader in the Palmer area, who was the first to own mechanical farming equipment, a binder and a threshing machine. The relatively moderate climate and rich soils were conducive to many crops, as shown in early photos of Valley farms.

Advertisement

G.H. Saindon’s ranch, four miles north of Matanuska Junction.

[Photo credit: University of Alaska, Fairbanks]

In 1914 Hugh H. Bennett, who made the first Valley soil reconnaissance, reported that a minimum of 1,000 acres had been cleared for cultivation in the Matanuska Valley, primarily near Knik and adjacent to the trails leading to the Willow District gold mines. By 1920 the cleared acreage had almost doubled, due in part to clearing fires set by the railroad construction crews and embers from the steam powered trains; after the wildfires died the farmers only needed to clear away the burnt stumps of the formerly forested land.

In 'Knik Matanuska Susitna: A Visual History of the Valleys', written by Pat O’Hara and a team of researchers and photographers and published by the Mat-Su Borough in 1985, “Homesteaders began settling around Matanuska as early as 1915 when a railroad clearing fire burned a large area between Matanuska and Palmer. For the next two years, potato and vegetable crops sold well, and by 1917, 400 settlers readied their farms for spring planting. The newly organized Matanuska Farmers’ Association constructed a building for root crop storage and a meeting hall in Matanuska.”

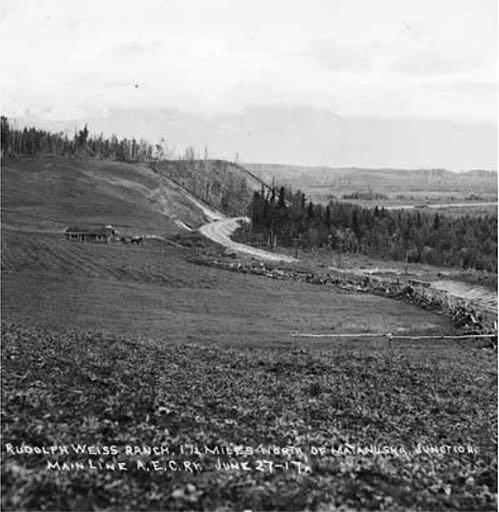

Rudolph Weiss ranch, 1.7 miles north of Matanuska Junction. June 27, 1917.

[Credit: University of Alaska, Fairbanks]

In 'Matanuska Valley Memoir,' Bulletin #18 from the Alaska Experiment Station, published in July, 1955, authors Hugh A. Johnson and Keith L. Stanton also describe early farming development: “Agriculture in the Valley came into its own in 1915. Most of the 150 settlers filing for homesteads came intending to farm. Some cleared enough land to put in a crop the next year. Settlement was concentrated in the vicinity of Knik, across the Hay Flats and up the Matanuska River with a few homesteads spotted along the trails leading to Fishhook Creek. The greatest influx of settlers occurred in 1916 and 1917. By the end of that period nearly all the available land had been homesteaded--a fact not commonly known.”

In 'Old Times on Upper Cook’s Inlet,' early historian Louise Potter printed a list of 132 people who had homesteads near Knik in 1915, noting, “That such a list is possible at all is apt to come as a surprise to many who have been encouraged to believe that 1935, the date the ’Colonists’ arrived in the Matanuska Valley, marks the beginning of the history of agriculture in the Upper Inlet Region...”

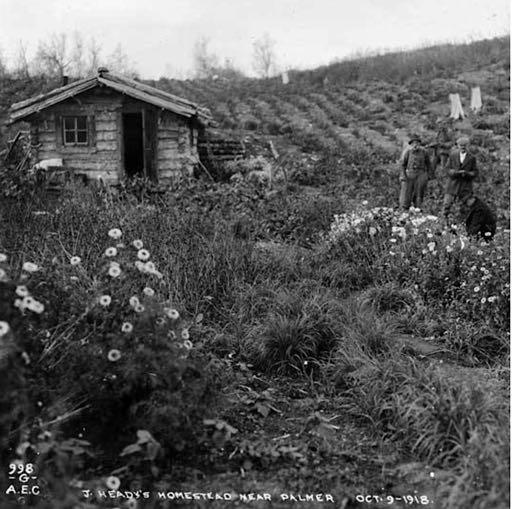

J. Heady’s homestead near Palmer, October 9, 1918.

[Photo credit: University of Alaska, Fairbanks]

Many Valley residents today still believe farming was introduced by the Colony Project, but the colorful history of that government experiment only marked a substantial increase in farming, not the beginning of it. In Vol. 1, No. 1 of 'Touchstone Magazine,' August, 1976, published by the Alaska State Fair, Inc., Tom Locke, author of 'Grubstaking the Great Land' (Alaska State Fair, Inc., 1975) provided some perspective: “First of all, it should be noted that Alaska was different from other American frontiers in that the second wave, farmers, never really materialized. The adventurers came, and the men with large capital followed, but the wave of hard-core pioneers never appeared. Alaska’s riches were reaped in the summer and transferred south in the fall. Thus, the arrival of the Matanuska colony farmers in 1935 brought hope of a more permanent settlement and expansion of the territory.”

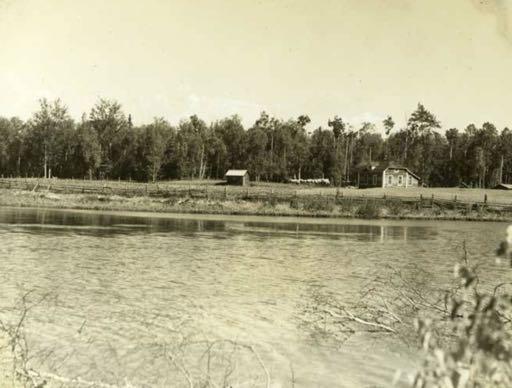

Kinsinger and Winchester Ranches, two miles north of Matanuska. June 27, 1917.

[Photo credit: University of Alaska, Fairbanks]

In fact, permanent settlement and expansion had been in the plans all along, as evidenced by the Agricultural Experiment Stations scattered across the land. Settler and entrepreneur George Palmer had been experimenting with the seeds he received from the Sitka Agricultural Experiment Station since 1900, when he wrote the following letter to Prof. C. C. Georgeson detailing his efforts at Knik:

Dear Sir:

Your favor of July 17 just reached me. When you learn that the nearest post office (i.e. Sunrise) is about 80 miles from here, and that I have to go in a small sailing boat, in perhaps the most dangerous water on the coast for small boats, you may know that I take a trip only when necessary; so my mails are few and far between. I have received no seeds yet, and it is hardly likely that another mail will reach me this fall, as navigation will soon close for the winter.

In regard to the seeds I planted last spring, will state that my knowledge of gardening is very limited, but have had very fair success so far. I have less than an acre in cultivation.

Parsnips are the finest and largest I ever saw, and the first I have heard of raised in the vicinity. Turnips grow to an enormous size, and of fine flavor. (Captain Glenn took a sample of my turnips last year to Washington.) This year my seeds were bad in some way, as most of them went to seed. I don’t know the reason why.

The Scotch Kale is a perfect success here. Two men who came here from where it is raised extensively say it was the finest they ever saw. Cabbage is small, but heading fast at present. They have heads about the size of a pineapple cheese, and are of a fine flavor.

Rutabagas are large and fine; have just taken mine into the root house. I had some so big that three filled a 30-pound candy pail.

Lettuce, peas, radishes, cauliflower, and potatoes are a success.

I made a failure of cucumbers, tomatoes, spinach, and parsley, and a partial failure of onions, but I think they could be grown from seed.

The natives above raised some potatoes, turnips, kale, cabbage, cauliflower, parsnips and radishes. They are very anxious to learn. I am a very poor teacher, as I must learn myself before I can teach others. Instructions about planting should go with all the seeds you send out. Some of the failures were due to my inexperience.

Yours, truly, G. W. Palmer.

Mr. A. A. Cobb’s cabin and a portion of his garden at Matanuska Junction, circa 1916.

[Photo credit: University of Alaska, Fairbanks]

Before 1914 the only domestic livestock in the Matanuska Valley, with the exception of a few chickens, were horses, used for transportation and hauling freight. The Hay Flats along Knik Arm provided abundant natural grasses for food, and were cut for winter hay, valued at $40 per ton, and a few additional acres of oats were grown for grain. In the spring of 1914 a bull, five cows, two calves, and six hogs were landed at the Knik dock for breeding stock on a ranch in the Cottonwood area. Around the same time Captain Axel Olson arrived with Holstein and Jersey cows, and the Laubner brothers and Dave Carsteads ranged cattle near the site of the old Fishhook Inn, on the road to the mines.

In an article for the Pacific Northwest Quarterly, October, 1978, James R. Shortridge wrote about the early government and private efforts to promote Alaska as an agricultural Promised Land: “...almost every promoter lauded the long summer days and their amazing effect on vegetable quality and size. One enthusiast called the tropical sun ‘too intense’ for best plant growth whereas ‘the slanted light of the higher latitudes is always soft and delicate, stimulating growth and not retarding it.’ According to some, these magical conditions impart to Alaskan produce ‘such superior flavor that when a person has once eaten the vegetables grown in Alaska, other vegetables are insipid and tasteless.’”

The Matanuska Agricultural Experiment Station, circa 1910-1915.

[University of Alaska, Fairbanks photo]

Johnson and Stanton’s 'Matanuska Valley Memoir' details the early agricultural developments in the Valley, explaining how the history unfolded: “When the 1917 season rolled around approximately 400 settlers prepared to plant a larger crop than ever before. The Matanuska Farmer’s Association’s building was ready for use in Matanuska Junction; construction on the railroad was proceeding at a rapid rate. The Alaska Road Commission had completed a new road from the Little Susitna Valley through Wasilla to Knik. Other plans called for constructing a network of roads to replace trails then in use.

“Prosperity seemed certain as the farmers took to the fields those first days of May 1917. But with the entry of the U.S. into World War I, Alaska was left in a state of almost complete stagnation. The war profoundly affected the Matanuska Valley.

“Alaska’s manpower answered the call to duty with characteristic enthusiasm. Men left undeveloped farms, unfinished construction, partially developed mines and industries. Railroad construction suffered immediately from lack of funds, scarcity of materials and lack of manpower. When the harvest was completed in September of 1917, the market had shrunk and a ruinous surplus of potatoes and vegetables resulted. The potato crop for 1917 was estimated at 1,300 tons. There still remained 600 tons of unmarketed potatoes in the spring of 1918. These were lost because there was no livestock to eat them.

“Because of this unsold surplus, many farmers failed. Swan Youngquist was reported to be the only farmer who made money in 1917. He sold directly to Anchorage residents. The Farmer’s Association was dissolved in 1918 and its debts were assumed by several men in the Valley, among them F. F. Winchester and Al Waters. Farming was too undeveloped and lacked reserve capital to survive these adversities. By 1920 less than 200 settlers remained in the Valley. Not until the Colonists arrived in 1935 did agriculture again move ahead.”

Greenhouse on the Harman Ranch neat Matanuska, June, 1917.

[A.E.C. photo, University of Alaska Fairbanks]

There were no roads from the Valley to the rest of Alaska at this time. Except for winter sledding trails and freight boats plying the dangerous waters of Knik Arm, the Matanuska Valley was isolated until the Alaska Railroad tracks reached it in 1916. Despite this dismal picture, there were encouraging developments in the Valley’s agricultural scene, starting with the building of the Matanuska Experiment Station in 1918. Once again Johnson and Stanton give a very detailed report in 'Matanuska Valley Memoir:' “M. D. Snodgrass, on the Alaska Engineering Commission’s recommendation, chose section 15, township 17 north, range 1 east of the Seward Meridian, which originally consisted of 240 acres as the location for the Matanuska Experimental Farm. Section 14 adjoining the 240 acres was later set aside for the station, making a total of 880 acres to be developed for experimental purposes. For the fiscal year ending June 30, 1918, $10,000 was appropriated for the station and work was begun under the direction of F. E. Rader on April 1, 1917.

Robert Lathrop, an old settler, cutting hay on Cottonwood Flats.

[Mary Nan Gamble Collection, ASL-P270-818]

“The first three years were spent in clearing land and erecting buildings. As soon as land was cleared, Rader began testing varieties of potatoes and grains. He also maintained a garden and nursery. Some machinery was placed on the farm.”

The somewhat dry report goes on and on, detailing the Experimental Farm’s testing of varieties of crops and grains, the participation of the farmers in the testing, problems confronting the homesteaders, individual stories of several successful farmers, and how the high freight costs and finding suitable markets was handled.

In 1920 the Experimental Farm began working with cattle, starting with five milking Shorthorns, then adding six Galloways from Kodiak and Holsteins which were cross-bred with the Galloways to develop a strain of dual-purpose cattle who could withstand rigorous Alaskan winters while being suitable for both beef and dairy production.

Also introduced by the Experimental Farm in 1920 was a flock of 16 Cotswold sheep: “This introduction interested several farmers in the sheep enterprise and they bought most of their foundation stock from the Station flock. By 1930 three farmers owned 221 sheep. J. W. Bogard, whose homestead was on the north shore of Finger Lake, owned the largest flock (he was instrumental in getting a road built through the region north of the lakes).”

Jacob Metz farm, near Wasilla, circa 1916

[A.E.C. photo]

By the late 1920’s several farmers had developed small dairy herds, and a cooperative arrangement between the Alaska Agricultural Stations and the Alaska Railroad resulted in the construction of a creamery at Curry, which meant a new market for the milk produced in the Matanuska Valley. While the remote community at mile 248 of the Alaska Railroad may have seemed like an odd choice for the creamery, its grand hotel was a popular and respected stop. The opulent Curry Hotel was described in Ken Marsh’s 2003 book, Lavish Silence: A pictorial chronicle of vanished Curry, Alaska (Trapper Creek Museum Sluice Box Productions, Trapper Creek, Alaska 2003): “The Curry Hotel, first opened in 1923, boasted amenities in a wilderness setting seldom seen even in large stateside establishments during this time. Tennis courts, a golf course, a swimming pool, a footbridge spanning the rolling width of the Susitna River and a winter ski lift, all helped make Curry world famous. Nothing was lacking for human enjoyment and comfort.”

Farm scene on Wasilla Lake, 1935.

[Mary Nan Gamble. Photographs, 1935-1945. ASL-PCA-270]

Marsh described the creamery as well: “Another Curry-based enterprise was operated for the benefit of farmers to encourage dairy farming along the Alaska Railroad. A creamery that turned out 1,434 pounds of butter in July and August of 1932, also made ice cream, table cream, buttermilk, cottage cheese and sweet milk. The dairy products were used at the Curry Hotel, in the Alaska Railroad dining cars, and Base Hospital at Anchorage. Other merchants purchase surplus products. The churns of the creamery were later moved to the Experiment Station at Matanuska since most of the cream came from that area as time went by.”

The completion of the 500-mile Alaska Railroad in 1923 promised to bring new opportunities for prosperity and economic growth, with renewed interest in agricultural development of the Matanuska Valley. A 1928-29 agricultural settlement program sponsored by the Alaska Railroad generated considerable interest, and more than 12,000 applications and requests for information were received from potential farm families. M. D. Snodgrass, the agricultural agent at the Matanuska Agricultural Experiment Station, interviewed six hundred applicants and selected fifty-five families for the Alaska Railroad Colony Project, but the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing depression caused many to reconsider moving to Alaska, and the Railroad quietly dropped its colonization project.

Alaska was still reeling from the effects of World War 1. Men who joined the Army or went Outside to take high-paying industrial jobs often did not return to Alaska, as the postwar prosperity in the rest of the United States was simply too satisfying. Alaska’s economy was in limbo, and in her book Early Days in Wasilla (1963), historian Louise Potter noted “estimates say that half the farms were abandoned.”

Joe Kircher’s farmstead.

[Mary Nan Gamble. Photographs, 1935-1945. ASL-PCA-270]

It was not until 1935 that the federal government’s Matanuska Colony Project boosted the area to become Alaska’s major farm belt. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration, one of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal agencies, planned and orchestrated an agricultural colony of 204 stricken farm families from the northern tier states of Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, believing the farmers of Scandinavian descent would have a natural advantage in the similar climate of the far north. By the standards of farming elsewhere, however, the production was quite minimal. Historian Orlando Miller, author of 'The Frontier in Alaska and the Matanuska Colony' (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 1975), noted in 1959: “….the cropland and production of the Valley could have been equalled in the corner of one county in a midwestern state.” The experiences of one Matanuska Valley farmer were detailed in 'Matanuska Valley Memoir,' a bulletin from the Alaska Experiment Station at Palmer, in 1955: “The oldest farm remaining under one ownership and in continuous production is that of John Bugge who homesteaded 320 acres in 1914. Bugge ceased farming actively in 1946, although he has continued clearing and renting land and raising hay. His farm is located contiguous to the western limit of the city of Palmer. “Bugge came to the Territory in 1900, living first in southeastern Alaska. In 1913 he arrived aboard the Northwestern at Ship Creek (Knik Anchorage) and from there traveled by launch to Knik. He joined the Nelchina stampede ‘necking’ a sled up the Matanuska River in company with Al Waters in the winter of 1913. Finding the region poorly suited to mining, they returned to take up homesteads in the Valley.

R. S. Heckey ranch about four miles north of Matanuska Junction, 1917.

[by P.S. Hunt, UAF-1984-75-517]

“In the spring of 1914, Bugge purchased a horse from Hughes, the freighter from Knik, and, in order to put up hay, located his present farm at Palmer shortly after the survey had been completed through that region. By that fall, Bugge had constructed his first house and had dug a well. His house served as a stopping place for people traveling through the Valley along the Matanuska River. He recalls that one night he put up 14 men and 13 dogs. During 1915, he began purchasing machinery for his homestead. That year he acquired a plow and the following year he added a drill, mower and rake to his collection. In 1917-18 he purchased a disc, binder, thresher and Fordson tractor. Previous to this, he had shipped a team of mares from the States at a cost of $600. A stallion shipped in by A. J. Swanson made it possible to raise three colts.

“Bugge was the first homesteader to acquire enough machinery for farming on a fairly large scale. His were the first tractor and the first thresher in the Valley. The experiment station acquired the second thresher. Because of his extensive collection of machinery, Bugge did custom binding and threshing for the settlers near him. Among some of these early homesteaders for whom he worked were Ross Heckey, John Springer, Arvid Bergstrom, and Adam Werner.

Another settler, Adam Werner, filed on a tract located northwest of Palmer. Werner came to the Valley in 1914, taking up his homestead at that time. He first trapped with a partner who later drowned in the Matanuska River. Until the late 1920’s, Werner trapped winters and developed his farm during the summer seasons, concentrating on farming and developing a dairy herd. He died in 1944 and his widow, Fannie, continued operating their Grade A dairy.

Carl Martin first came to the Valley in 1909 in the company of ‘Tex’ Cobb. They traveled from Knik to the Cache Creek prospecting country. Later Martin returned to the Valley and took out a homestead near Matanuska Junction. By removing and burning the trees after a railroad clearing fire in 1915, Martin grew several acres of potatoes in 1916. Most of these he sold to the railroad. In 1917 he harvested 60 tons of potatoes and 1,500 heads of cabbage and cauliflower despite a hard freeze on September 3 of that year.

Most of the early Matanuska Valley farmers earned little more than a subsistence lifestyle. The national prosperity which followed World War I did not include Alaska, and Congress seemed little concerned with supporting a territory it had only reluctantly purchased. There was little incentive to develop the remote, rugged land, far removed from the concerns of most Americans, and consequently, capital was simply not made available.

By 1920 the farmers who had enjoyed the boom times in 1914 and 1915, when new markets had been available, found the post-war economic conditions dire. The population had fallen off, farms were idle, and fields formerly cultivated were being reclaimed by the fast-growing brush. The only markets were Anchorage and the thinly populated railbelt, and high transportation costs discouraged attempts to reach more distant markets. A 1923 survey to determine the number of homesteaders and their farming operations showed that nearly two-thirds of the Valley’s farmers (105) were not enumerated because they were employed away from home at the time, primarily in the mines, on the railroad, or with the Alaska Road Commission.

Addressing this in 1955’s 'Matanuska Valley Memoir,' authors Hugh A. Johnson and Keith L. Stanton optimistically wrote: “Temporary set-backs in area development are to be expected. The upward trend of progress is always marked by temporary downward dips. Alaska may not now be ripe for the industrial revolution occurring in the Pacific Northwest, but it has certainly been impregnated with ideas of a prosperous future. Young people and a young country make a combination hard to beat.” ~•~

Olaf Wagner's farm at Wasilla with potatoes in bloom, 1923. Large field of potatoes with lake in background. Tinted slide from The Alaska Railroad Tour Lantern Slide Collection, 1923.

Alaska State Library ASL-PCA-198-23