6 minute read

1915 TANANA CHIEFS CONFERENCE

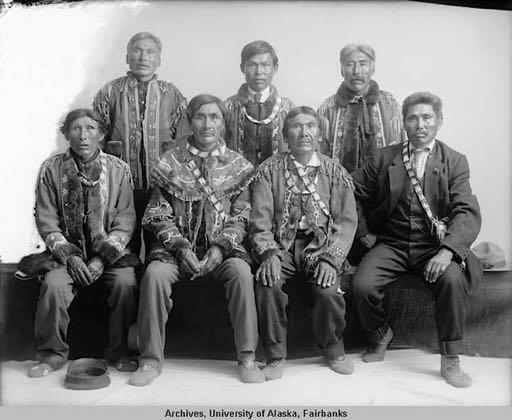

Group portrait at the first Tanana Chiefs Conference, 1915. Seated front, L to R: Chief Alexander of Tolovana, Chief Thomas of Nenana, Chief Evan of Koschakat, Chief Alexander William of Tanana. Standing at rear, L to R: Chief William of Tanana, Paul Williams of Tanana, and Chief Charlie of Minto. [Albert Johnson Photograph Collection, University of Alaska Fairbanks.]

The 1915 Tanana Chiefs Conference

Advertisement

On the corner of First and Cowles Streets, neardowntown Fairbanks, sits an unusual square log building, with a hip roof extending over a wide porch along two sides. The main entrance is located at the corner of the building, giving the entire structure an air of being something special, which, in fact, it is. Built in the summer of 1909 with money donated by a philanthropist who never set foot in Alaska, the structure was the site of a landmark gathering in Alaska’s history, when Native chiefs and government representatives met to discuss the future.

The George C. Thomas Memorial Library was named for a Philadelphia banker who, after learning of efforts to supply reading materials for Alaskan pioneer settlers, donated $4,000 for its construction. The 40 by 40 foot log building was dedicated on August 5, 1909, with the Honorable James V. Wickersham, Territorial Delegate to Congress, attending, along with Archdeacon of the Yukon Hudson Stuck and other local notables. Unfortunately, the philanthropist, George C. Thomas, died before the opening of the library, but he left $1,000 per year for maintenance of the library for three years.

The George C. Thomas Library in July 2011, looks almost the same as when it was built 102 years before.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_C._Thomas_Memorial_Library

The Tanana Chiefs Conference brought together Native Athabascan leaders from the Tanana River villages ofCrossjacket, Chena, Minto, Nenana, Salchaket, Tanana/Ft. Gibbon, and Tolovana to meet with government officials to discuss the many changes happening in the Territory of Alaska at that time.

Taking place July 5 and 6, 1915, the government officials at the Council included Judge James Wickersham, Thomas Riggs of the Alaska Engineering Commission, C. W. Richie and H. J. Atwell of the U. S. Land Office, and the Reverend Guy Madara from the Episcopal Church. Also present were interpreter Paul Williams of Ft. Gibbon and G. F. Cramer, Special Disbursing Agent of the Alaskan Engineering Commission.

The transcript of the meeting is at the Alaska State Library [ASL-MS-0107-38-001], and it is a compelling read for anyone interested in Alaskan history, clearly showing the simple clarity and intelligence of the Indian words, and the paternalistic assurances of the white men present.

The transcript of the meeting is at the Alaska State Library

Alaska State Library, ASL-MS-0107-38-001

In March, 2018, the University of Alaska Press published The Tanana Chiefs: Native Rights and Western Law, edited by UAF Emeritus Professor William Schneider, noting about the meeting, “It was one of the first times that Native voices were part of the official record. They sought education and medical assistance, and they wanted to know what they could expect from the federal government. They hoped for a balance between preserving their way of life with seeking new opportunities under the law.”

Schneider explains further in his Introduction: “For Native leaderds and students of Native history, the record of this meeting is a baseline for measuring progress in areas such as governmental relations, recognition of legal rights, land claims, health care, social services, and education. The meeting is also important because it demonstrated the leadership of the Native chiefs, who stated their concerns and expressed their desire to work with the federal government, even though they couldn’t agree with all that was asked of them.”

The Tanana Chiefs and others, by Albert J. Johnson. Standing in the back row (left to right): Julius Pilot, Nenana; Titus Alexander, Hot Springs, Mr. Cramer, Mr. Th (Thomas) Riggs, Mr. Richie, Chief Alexander Williams. Seated (left to right): Jacob Starr, Tanana; Chief William, Tanana; Chief Alexander, Tolovana; Chief Thomas, Nenana; Hon. James Wickersham; Chief Evan of Coschaket; Chief Charlie, Minto. Front row (left to right): Chief Joe, Salchaket; Chief John, Chena; Johnnie Folger, Tanana; Rev. Guy H. Madara; Paul Williams, Tanana.

University of Alaska Fairbanks, Albert Johnson Photograph Collection UAF-1989-166-37

In a book review for the Anchorage Daily News titled “How 14 Athabascan tribal leaders set the course of Native rights in Alaska,” Fairbanks author and literary critic David A. James reviewed Schneider’s book, writing, “While he failed to fully understand the Athabascan point of view, there’s no doubt Wickersham wanted to find a way to protect them before they were overwhelmed by the influx.

The transcript of the meeting shows the gulf in the world-views that existed between, on one side, Wickersham and other officials, and on the other, the chiefs. Steeped in 19th century methods of resolving conflicts with Native Americans, Wickersham believed a reservation was the best solution. The chiefs were having none of it. They approached the meeting not as wards of the U.S. government (the Treaty of Cession had put them under the care of the government but denied them citizenship), but rather as the leaders of sovereign nations — meeting as equals, not supplicants.”

This can be seen in some statements from the conference: Paul Williams: "Then, you people will understand that we natives have decided to keep off the reservation, and do not wish to go on a reservation at all. But our next suggestion, that we wanted and of course which we shall wish the Delegate to bring up for us and see what he can do for us about it, ….we have decided that we all wish to ask the Government if they couldn't get us some industrial schools. If they wish to help the Indians, the natives, that is the best thing the Government could do for us.…”

Then there is much discussion of boarding schools, and also of doctors and job opportunities for the Native peoples. Paul Williams interprets the words of Chief Ivan, of Crossjacket, to Delegate Wickersham: “He wants you to understand that he thinks it is very simple for the Government to do anything when it wants to, because the Government has a good people and citizens to support it, but the chiefs have people who cannot support them if they want to accomplish anything so they cannot do these things, but the Government can. So they came all the way up here at their own expense to show you how anxious they are to have the Government help them.”

To which Delegate Wickersham replies: “Paul, you tell them I say I think it has done a great deal of good. We have seen them now and know them and are acquainted with them, and have written down all they said and will send it to the Secretary of the Interior, and a copy of their pictures too, so that the Secretary of the Interior will look at their picture and look into their faces and see what kind looking men they are, and he will read here about what they want, about them wanting schools and work and that they want to make homes and want to become like white people and want to learn to talk the white man’s language, and to work like the white men. The Secretary of the Interior has charge of all these matters you have brought up. He has charge of the railroad and of the lands and I think he will feel very friendly to you. But you tell them, Paul, that it all depends finally upon the Indians themselves. If they work good they will be employed. If they work bad they won’t be employed. So it all lies with the Secretary of the Interior and the Indians.” ~•~

Read and/or download the entire 33-page transcript of the Tanana Chiefs Conference at: https://vilda.alaska.edu/digital/collection/cdmg22/id/162/