10 minute read

1898 IN THE MATANUSKA VALLEY

Original article header art by Jon Van Zyle.

“We rounded Cape Elizabeth in the early morning of May 31, and consumed the remainder of the day and until nearly midnight in reaching Tyoonok, at which place we found scattered along the beach from 200 to 500 prospectors, about 100 Indians (men women and children) and the trading station of the Alaska Commercial Company. This place is generally considered to be the head of navigation in Cooks Inlet, but I subsequently ascertained that excellent anchorage, plenty of water, and a safe harbor, were obtainable at Fire Island, which is situated between the mouths of Turnagain Arm and Knik Inlet, a distance of about 18 miles farther up the inlet.”

Advertisement

Captain Edwin F. Glenn, Twenty-fifth Infantry, United States Army, was the officer in charge of explorations in southcentral Alaska in 1898. The main task of ‘Military Expedition No. 3,’ under the War Department, was to explore the country north of Cook Inlet in order to discover the most "direct and practicable" route from the coast to the Tanana River by utilizing passes through the Alaska Range. Captain Glenn was charged with collecting and reporting on all information that was considered valuable to the development of the country, so his descriptions of the expedition are a fascinating look at one of the earliest official government incursions into the Cook Inlet and Matanuska regions, and northeast into the Copper River Basin.

Captain Glenn kept a diary of his travels, which is available to download or read free online at the UAA/UPC Consortium Library website (see Resources for this issue, page 48). His sometimes blunt and unvarnished writings illuminate the many trials and travails which beset the expedition, but they also give voice to a keen observer of the world - and men - around him.

“The Matanuska Valley is at present reached from Knik, which is the head of navigation on Cook Inlet, and to which vessels of shallow draft can go at high tide. Near the lower end of Knik Arm there is a good anchorage, which ocean going vessels can reach at any stage of the tide except during the winter, when the whole upper part of Cook Inlet is frozen…” -W. C. Mendenhall, 1898

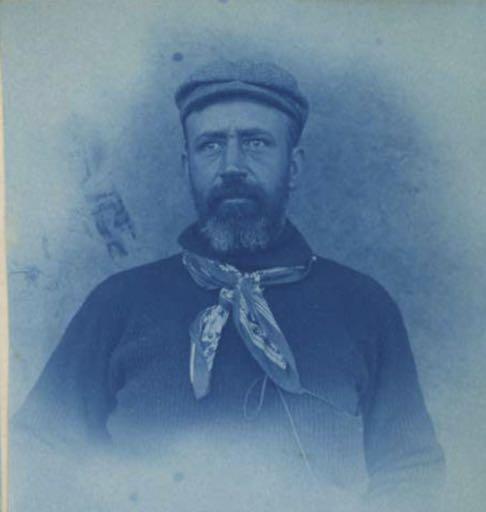

Cyanotype portrait of Captain Edwin F. Glenn, leader of the 1898 Cook's Inlet Exploring Expedition, taken at Tyonek in October 1898. He is wearing a hat and sweater, and has a print kerchief knotted around his neck. Photograph taken during the expedition. This may be a selfportrait taken by Glenn.

[Edwin F. Glenn papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage. ]

“We reached Knik Inlet finally, cast anchor, and waited for the vessel to go aground before attempting to unload. We were deeply impressed with the appearance of everything in this inlet. The weather was much more mild than in the lower part of the inlet, and the season more advanced than at Tyoonok or at Ladds Station by at least three weeks. The trees were in almost full leaf, and the grass a sort of jointed grass resembling the famous blue grass of Kentucky was abundant and at least a foot high. The length of this arm is about 25 miles. Coming in at the head of it were the Matanuska and Knik rivers, the former from the east, the latter from the south. The valley there is quite flat and about 20 miles across. In fact, the valleys of both streams are in full view from just above the trading station.

Knik Glacier in the Chugach Mountains. The Lake George jökulhlaup formed near the base of the glacier and emptied into the Knik River.

[Photo by Helen Hegener/ Northern Light Media]

“This inlet, when the tide goes out, seems to be an immense mud flat. I learned from reliable sources that about two years ago the navigable channel of this inlet passed directly in front of and close to the trading station. But it seems that at that time an immense body of water came down, apparently from the Knik River, destroying not only the trading establishment of the Alaska Commercial Company, located on the opposite bank of the inlet, but also a number of Indian houses. The Indians say that as this flood came down it presented a solid wall of water at least 100 feet high. This statement, however, should be very much discounted. At any rate, the effect, in addition to the destruction of the houses, was to leave deposited in front of the present trading company's establishment an immense amount of mud and sand that extends out from the shore for nearly if not quite half a mile, and prevented us from landing at the station. We were forced to cast anchor at the mouth of the small stream, two miles below, that is used by the Knik Indians during the fishing season.”

USGS geologist Walter Curran Mendenhall (1871-1957) travelled with Capt. Edwin F. Glenn in 1898.

The “immense body of water” referred to by Captain Glenn was well documented as a significant event in the Valley’s history. Lake George, a glacial lake formed near the face of the Knik glacier, received recognition by the National Natural Landmark Program because of a unique natural phenomenon called a jökulhlaup, an Icelandic term for glacial lake outburst flood. The intermittent breakup of the lake’s ice dam would send a violent wall of water, ice and debris down the valley causing massive flooding and sometimes devastation to settlers' properties. The Lake George jökulhlaup has not occurred since 1967, due in part to glacial recession, but also for reasons associated with the massive Good Friday Earthquake of 1964.

Geologist W. C. Mendenhall, a member of Captain Glenn’s expedition who would go on to a distinguished career (including Director of the USGS from 1930 to 1943), made the first rough geological survey of the Matanuska Valley and the routes followed by Glenn. He mentioned the guide, Mr. Hicks, who had been prospecting in the area for three years, in his official report for the Twentieth Annual Report for the USGS, Part VII, Explorations in Alaska in 1898 (also available to read online, see page 48): “Among the prospectors at the head of Cook Inlet but one was found who was acquainted with the Matanuska country. This gentleman, Mr. H. H. Hicks, Captain Glenn was so fortunate as to secure as a guide for the expedition, but neither he nor anyone else could give us any definite idea of the character of the interior beyond the head of the Matanuska.”

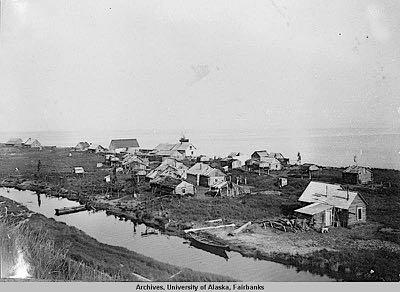

The village of Tyonek. [UAF]

Mendenhall's explorations covered areas on the west shore of Prince William Sound and a route extending from Resurrection Bay to the head of Turnagain Arm, thence by way of Glacier and Yukla Creeks [Ed. note: the current Eagle River] to Knik Arm, up the Matanuska Valley to its head, and thence northward to the Tanana. He wrote from Ladds Station; “We waited here till the 19th of July, when Captain Glenn determined to buy a pack train which he had learned was for sale at Sunrise City. On the 22d the steamer Perry landed us at Knik Station with the animals (25 head), and the next morning we started up the Matanuska Valley, bound for the Tanana. The start should have been made two months earlier and the time for our work thus practically doubled, but the question now was one of accomplishing as much as possible in the short time remaining before freezing weather should set in.”

Under the heading ‘General Description of the District,’ the Matanuska River is described: “Matanuska River is tributary to Knik Arm, at the head of Cook Inlet. It rises on the western edge of the Copper River basin and flows between the Talkeetna Mountains on the north and the Chugach Mountains on the south. The Matanuska is about 80 miles in length…”

After describing the the Matanuska River’s attributes and tributaries, relative heights and characteristics of the mountains, and vegetation in the Valley, Mendenhall’s report turns to accessibility: “The Matanuska Valley is at present reached from Knik, which is the head of navigation on Cook Inlet, and to which vessels of shallow draft can go at high tide. There is a good horse trail from Knik to the upper end of Matanuska Valley, and the character of the ground and of the vegetation is such that this trail could be made into a wagon road at comparatively slight expense. It takes horses from one to two days to reach Moose Creek, depending on the load, and … a day and a half to go from Moose Creek to Chickaloon River.

Looking down the Matanuska River from Glacier Point. Matanuska District, Cook Inlet Region, Alaska. 1898.

[Photograph by W.C. Mendenhall, 39 - mwc00039 - U.S. Geological Survey. Photo id: 253662]

“At present freight can not be taken in while Cook Inlet is frozen, which is usually from October 15 to May 15, and passengers can reach the region during the winter only by going in from Seward with sleds. The Alaska Northern Railroad, which is now completed from Seward to Kern Creek, on the north shore of Turnagain Arm, a distance of 72 miles, is intended to reach the Matanuska Valley, to which surveys have been made; some construction work has been done between Kern Creek and Knik Arm. According to the present surveys it will be about 150 miles from Seward to Chickaloon River. When this road is completed the Matanuska Valley will be easily accessible at any time of the year.”

Mendenhall also described the first peoples of the Valley: “The native inhabitants of the region about the head of Cook Inlet belong to the true Indian stock, as distinguished from the Eskimo tribes of the coast. They are now collected into a few small villages, as at Tyonek, Ladds Station, and Knik, where their original customs have been much modified by white traders, upon whom they are becoming more and more dependent. Physically they are slight and will average less in stature than the whites. They are good-natured, timid, disinclined to quarrel, and are generally honest, although idlers. They still depend in a measure upon the summer's catch of salmon to keep them from starvation during the winter season, but secure clothing of white manufacture and many articles of food from the stores of the various trading companies in exchange for furs. Their winter habitations are rude cabins, which are sometimes occupied throughout the summer months also, but are quite as often discarded for tents until severe weather begins again. Pulmonary and inherited diseases are making constant inroads on their numbers, particularly at the stations, where their native customs have been most modified by white influence. The Indians of Knik, for instance, are much more robust than those at Ladds Station.”

“Cook Inlet and Prince William Sound have a semi-permanent white population, consisting of traders, claim owners, prospectors, fishermen, and Russians, some of whom stay in the country from year to year, others going to some point in the States occasionally to spend a winter. A much larger percentage of the whites found there in the summer, however, are transients, who never winter in the country.

"The principal trading and mining centers are Sunrise, Hope, Tyonek, and Knik, and in these camps or the mining regions adjacent to them most of the whites may be found. A few each year penetrate some distance beyond the borders of the well-known districts and reach the interior of the Kenai Peninsula or prospect within the Matanuska Valley. Two small parties this year (1898) succeeded in getting nearly across the Copper River Plateau, and a few hardy traders or prospectors in previous years have reached the interior, but they have left no records."

And finally, Mendenhall described the Valley as an access route to interior Alaska: “From the head of Knik Arm the Copper River Plateau and all of the interior accessible from it is reached by way of the Matanuska Valley. For the greater part of the way from Palmer's store on Knik Arm to Tahneta Pass, at the head of the river, travel is easy. A sharp climb of 1,000 feet after crossing Chickaloon Creek, a little rough work in getting across the canyon of Hicks Creek, and a short steep climb out of the valley of Caribou [Creek], are the principal obstacles. The Tazlina River heads east of this gap, and by following it the Copper will be reached a few miles above the new town of Copper Center. This route has been followed by the Copper River Indians for many years in their annual trading trips to the stores on Cook Inlet.” ~•~

The Matanuska River near Palmer, route to the Copper Basin.

[Photo: Helen Hegener/Northern Light Media]