12 minute read

Woodchopper Roadhouse

North elevation from northwest - Woodchopper Roadhouse, photo by Jet Lowe. [Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress HABS AK,23-CIRC.V,3--2]

Advertisement

Photo by Cris Allen, National Park Service, 2010

Donald J. Orth’s encylopedic Dictionary of Alaska Place Names (USGS, 1967), which traces its roots to the 1902 USGS publication Geographic Dictionary of Alaska, notes the probable origin of the name ‘Woodchopper,’ as applied to the roadhouse and the creek for which it was named:

“Local name found on a manuscript by E. F. Ball dated 1898 and on a fieldsheet prepared by A. J. Collier, USGS, in 1902. The name may allude to woodchopping on the banks of this stream to furnish fuel for river steamboats.”

Woodchopper was also the name of a mining camp established in 1910 to mine coal in the area. The Circle Mining District records a list of 320 individuals whose names appear connected to claims on Coal Creek, Woodchopper Creek and their various tributaries. Coal claims were the first claims staked in the drainages, as steamboats plying the Yukon River between St. Michael on the Bering Sea and Dawson City and Whitehorse in the Yukon Territory would burn upwards of a cord of wood each hour, and the transportation companies saw coal as a potential alternative to wood, provided it could be located in sufficient deposits, mined and transported to the riverbank.

Cabin South and East Sides - Woodchopper Roadhouse, by Jet Lowe.

[Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress HABS AK,23-CIRC.V,3–3]

The first placer gold mining claim was filed on Coal Creek in mid-November 1901, by one Daniel T. Noonan, of Delamar, Nevada. Noonan located his 20-acre claim on the right limit of Coal Creek on August 23, 1901. The same day, Daniel M. Callahan also located a 20 acre mining claim in the vicinity of Noonan's claim. Over the next 48 years there were 565 claims filed on Coal and Woodchopper Creeks. According to the 2003 publication, The World Turned Upside Down: A History of Mining on Coal Creek and Woodchopper Creek, Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve, Alaska, by historian Douglas Beckstead (U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service), "During 1905, L. M. Prindle, of the USGS, reported that Coal Creek, Woodchopper Creek, Washington Creek and Fourth of July Creek produced at least $15,000. According to several unsubstantiated reports, the figure had a potential to rise as high as $30,000. Alfred H. Brooks, also of the USGS, reported the same year that the majority of this production came from Woodchopper Creek."

Woodchopper Creek was known to provide fuel for the 75 to 100 steamboats plying the nearby Yukon River at that time. The steamship companies contracted with woodchoppers to have the wood ready, and various woodyards were established along the Yukon River. On one upriver trip in 1905, a steamer stopped three times between Circle and Eagle to take on a total of 54 cords of wood. The cordwood piled on the bank in a 1926 photograph of Woodchopper Roadhouse indicated that Woodchopper was a regular stop on the steamboats’ route.

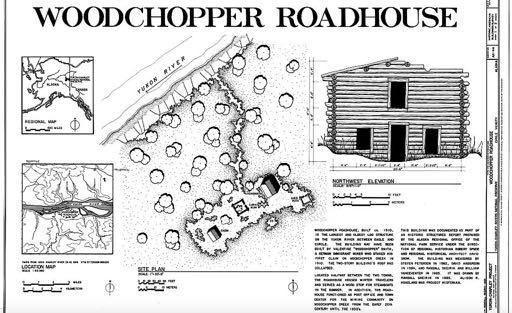

Woodchopper Roadhouse, built ca. 1910, was the oldest and largest log structure on the Yukon between Eagle and Circle. Located halfway between the two towns, on the left bank of the Yukon, approximately one mile upriver from Woodchopper Creek and 55 miles upriver from Circle, the roadhouse housed winter travelers and served as a wood stop for steamboats in the summer. In addition, the roadhouse functioned as the post office and town center for the mining community on Woodchopper Creek from the early 20th century until the 1930s. No exact date can be attached to this structure, but it is thought that this building was built at about the time the mining on Woodchopper Creek began to thrive.

Woodchopper Roadhouse as seen from the Yukon River, June, 1929.

The two-story building is constructed of round logs, saddlenotched. The second floor was partitioned into four rooms. The interior walls and ceiling were covered with a canvas or linen material, and the board floor was covered with linoleum, which has been destroyed by flooding. Moss chinking between the logs was covered with cement sometime after construction. Outbuildings appearing in a 1926 photograph include a gable-roofed shed west of the roadhouse, a cabin west of the shed which appeared to be for residential use, dog barns west of the cabin, and a shed northeast of the roadhouse which had lapjointed corners.

In the 1917-18 Polk's Directory, Valentine Smith, a miner, was listed as running a roadhouse on Woodchopper Creek, which was probably this building. Born in Germany in 1861, Valentine Smith immigrated to the U.S. in 1883, first staking a gold claim on Colorado Creek, a tributary of Coal Creek, in 1905. He later staked more claims in association with Frank Slaven and others, and in 1910 he staked his first claim on Woodchopper Creek. It is not known exactly when he began running the roadhouse, but on July 20, 1915, Art Reynolds, on a trip upriver from Circle, “stopt at Mr. Smith’s awhile. He gave us a salmon. Came about four miles above his place, camped for night.”

In 1919 Valentine Smith turned the running of the roadhouse over to Fred Brentlinger, also a miner, who, with his wife Flora, owned a number of lots in Circle, including the Tanana Hotel and Restaurant that they operated in 1911-12. They continued to become increasingly involved in the business community in Circle, with Fred Brentlinger serving as a notary public. Between 1919 and 1929 the Brentlingers left Circle and ran the Woodchopper Roadhouse while staking claims on Caribou, Coal, and Woodchopper Creeks.

When Fred Brentlinger passed away in 1930, Jack Welch and his wife Kate purchased the Woodchopper Roadhouse from Flora Brentlinger. She went to Manley Hot Springs where, along with Miner George McGregor wrote to his former partner, Frank Rossbach, in July, 1933: "A fellow by name of Jack Welch and his wife runs the roadhouse now, or at least she runs it, she is certainly the boss. Welch himself is a pretty good fellow. But different with her. She also has the post office."

C.M. "Tex" Browning, she purchased the Manley Hot Springs farm from Frank Manley. They retained the farm until 1950 when Bob Byers, operator of Byers Airways, bought it from them.

“U.S. mail leaving Woodchopper Creek. January (?), 1912. Beiderman, driver.”

NPS photo.

It is unclear how long the Welchs had lived in the North Country, as no record was ever located for when they arrived. Jack held the winter mail contract between Woodchopper and Eagle, and he would run his dogteam through the roughest weather to see that the mail got through. But Jack lost the mail contract sometime around the late 1930s, as airplanes were replacing dog teams for carrying mail. Undaunted, the Welchs stayed on at the roadhouse.

The owners of the Ed Biederman Fish Camp held the mail contract from 1912 to 1938 with only a few interruptions, and they used the Woodchopper Roadhouse as a winter stopover on the mail trail, which followed the frozen Yukon River. The numerous dog barns and dog houses at Woodchopper were used to house the Biederman dog team as well as those belonging to the owner and other visitors.

A visitor to Woodchopper in 1934, Elizabeth Hayes Goddard, was traveling the Yukon River alone and wrote in detail about her stay at the Woodchopper Roadhouse, noting that Kate Welch’s “goodnatured husband is tall and bent, [and] an unruly mop of black and grey hair sticks out over his forehead.”

Elizabeth Goddard described the accommodations as well: “Welch's home is made of logs, inside and out... In one corner are shelves of the store which sells canned milk, tobacco, candy, gum and other small articles. In another corner stands the desk which comprises the Woodchopper Post Office. In the third corner is the cooking range. A tin washbasin with towels for community use stands in the fourth corner near the stairway leading to the sleeping room above. A long dining table is near the stove.”

One spring a huge ice dam piled up in Woodchopper Canyon, five miles below Coal Creek. Miners Ernest Patty and Jim McDonald were spending the night in a cabin located at the mouth of Coal Creek, and in his book, North Country Challenge (D. McKay Co., 1969) Patty described the breakup: “At about three o'clock in the morning, loud crashing sounds woke us up and we jumped out of bed. The river had gone wild with the crushing force of the breakup. Normally the Yukon, at this point, is less than a quarter-mile wide. While we slept, the water level had risen fifteen feet. Rushing, swirling ice cakes were flooding the lowland on the opposite bank, crushing the forest of spruce and birch like a giant bulldozer. Before long ice cakes were being rafted up Coal Creek and dumped near our cabin.

“Then at the same moment we both turned and look at each other. The rapid rise of the river could only come from a gigantic ice dam in Woodchopper Canyon, some five miles downstream. Jack Welsh and his wife lived in that canyon. Their cabin must be flooded and probably it had been swept away. There is no way of knowing if they had been warned in time to reach the nearest hill, half a mile from their cabin. No outside help could possibly get to them now.”

Jack Welch, left, Ed Biederman, right

The entire tragic tale of Jack and Kate Welch is told in chapter two of The World Turned Upside Down, and author Douglas Beckstead continues the story: “As it turned out, the howling of their dogs awakened the Welchs. They found ice water covering the floor of the roadhouse. Jack ran outside and cut the dogs loose allowing them to reach higher ground on their own. Some made it. Some did not. Jack returned with his boat intending to take his wife and make a run for higher ground himself. At that point, the bottom floor of the roadhouse was under water and the second floor already awash. As huge cakes of ice slammed against the outside walls, Welch tied the boat to a second story window deciding that it would be better to stay with the cabin until the very last moment because the ice could crush his boat. Jack used a pole in an attempt to deflect ice cakes from hitting the cabin. As they waited, the water and ice continued to rise higher and higher until it finally stopped and slowly began to drop. This meant the ice dam was beginning to break. Now the ice cakes were coming with increased frequency and force. In the end, both the roadhouse and the Welchs survived. Years later, Ernest Patty noted that ‘perhaps it would have been more merciful if they had been swept away.’”

Beckstead explains why: “The terror these two elderly people experienced left deep scars. Neither fully recovered from this night of rising floodwaters and crashing ice. Consequently, Mrs. Welch became bedridden. As time passed, people began to comment that Jack was ‘getting strange.’”

Due to the terrors experienced that awful night, and perhaps exacerbated by his penchant for drinking to excess, Jack Welch began suffering from nightmares, and one night he awoke trembling, in a cold sweat, believing that the German Army was marching down the frozen Yukon River, coming for him. He decided that he was losing his mind and would be better off dead, and so attempted suicide with his .22 rifle, but only managed to wound himself. Although crippled with rheumatism, Kate hobbled two miles over the winter trail through the snow to seek help from their nearest neighbor, George McGregor.

Beckstead continues the story: “McGregor hitched up his dogs, and placing Mrs. Welch in the sled they returned to help Jack. After giving him first aid, McGregor loaded Jack into the sled, making a run up Woodchopper Creek to the mining camp where the winter watchman sent a radio message to Fairbanks. Several hours later a plane arrived and took Jack to the hospital in Fairbanks. Within a month Jack was up and around again. Nevertheless, the shock was too much for Mrs. Welch. She lingered on for a short time after Jack left the hospital until her tired old heart finally gave out.”

Kate’s death further unhinged Jack’s mind. Unable to accept that she was gone, he returned to the Woodchopper Roadhouse, expecting to find her waiting for him. When she wasn’t there Jack became distraught, and his concerned friends and neighbors radioed the U.S. Marshal's office in Fairbanks requesting that they come and take him back to the hospital.

But it wasn’t to be. Before the authorities could arrive Jack disappeared down the Yukon River in his boat. Some time later reports filtered back from villages along the lower Yukon of a mysterious elderly white man drifting down the river in a small boat, unresponsive to attempts at communication. Eventually reports came back from some Natives hunting on the Yukon delta of a man standing in a boat, shielding his eyes against the harsh western sun while looking out to sea. Jack and his boat floated out into the Bering Sea and were never seen again.

Jack Welch cutting salmon on the Yukon River, 1934.

After the Welches were gone the roadhouse was abandoned to the elements. The history of the roadhouse continues in outdoorsman Dan O'Neill's book, A Land Gone Lonesome: An Inland Voyage Along the Yukon River (Basic Books, 2008): "The Woodchopper Roadhouse was salvageable when Melody Webb surveyed it for the Park Service in 1976. As the largest structure in the preserve to still have its roof on, she recommended it be restored 'if a lodge is ever needed for the Park. A National Register would give added protection.' But by 2003, the roadhouse lay 'in ruins, the roof caved and the upper story fallen in,' according to a Park Service pamphlet." ~•~

Woodchopper Roadhouse, Yukon River, Circle, Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska.

Historic American Buildings Survey, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540. HABS AK,23-CIRC.V,3- (sheet 1 of 2)