14 minute read

BUILDING THE ALASKA RAILROAD 1902-1923

Workers on completed spans of the Matanuska River railway bridge, August 23, 1916. [Photograph by Alaska Engineering Commission photographer P. S. Hunt]

Gold, coal, timber and other natural resources were the motivating factors in the construction of early railroads in the territory of Alaska, and there were many railroads, by one count over thirty, from the far western reaches to the Panhandle. Many of these railroads were built and operated by mining interests, others were funded by farsighted groups or individuals who understood the potential profitability of steel rails providing reliable access to a new and growing land.

Advertisement

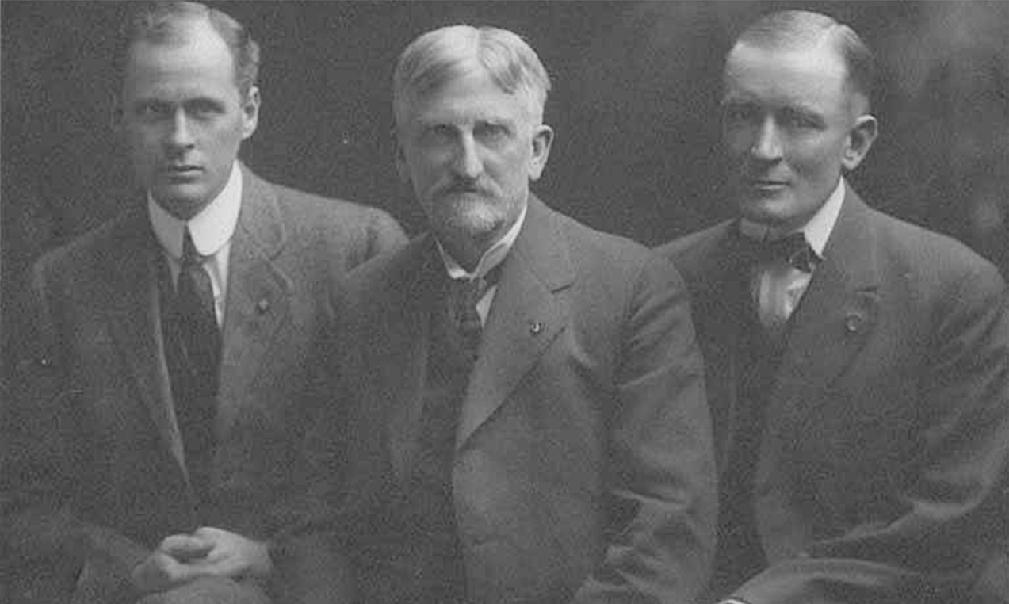

Alaskan Engineering Commission, created in 1914 to arrange for and facilitate construction of the railroad. L-R: Frederick Mears, William C. Edes, and Thomas Riggs, Jr.

[Alaskan Engineering Commission photo]

President Wilson appointed the Alaskan Engineering Commission in May, 1914, under the authority of the Secretary of Interior Franklin K. Lane, who appointed three men to the new Commission:

• William C. Edes, Chairman and Chief Engineer, a senior railroad engineer who had been locating and building railroads for 40 years. Edes had been the chief engineer on the Northwestern Pacific Railroad in California since 1907.

• Lt. Frederick Mears had been a railroad engineer for the Great Northern Railway. He fought in the Philippines before turning to the construction and operation of the Panama Railroad in Central America, where he was promoted to General Superintendent.

• Thomas Riggs, Jr. joined the Klondike gold rush in 1897, prospecting near Dawson City. He was the chief surveyor on the International Boundary Commission, locating the border between Alaska and Canada between 1906 and 1913, and he advanced to U.S Engineer-in-Charge as the team surveyed the rugged boundary from the Pacific to the Arctic Ocean. Riggs was wellknown in Alaska, and he would later serve as Territorial Governor of Alaska from 1918 to 1921.

The task set before these three experienced and very capable men was to reconnoiter and survey the potential railroad routes in Alaska. There had been sharp debating in Congress over the best route for the new government railroad, and survey parties were sent forth to assess every possible route, while all of the territory held its collective breath to see which would be selected, and where the rails would run from tidewater to the Interior of Alaska.

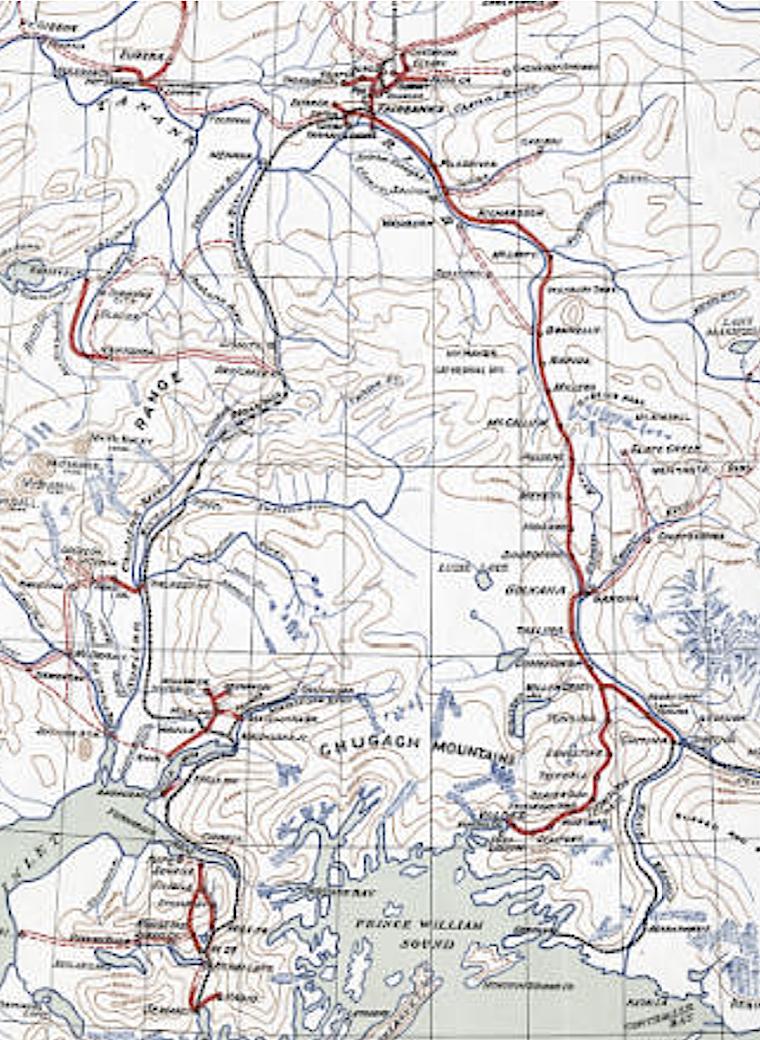

During the summer of 1914 there was thorough analysis of the Alaska Northern and Tanana Valley Railroads in the west, and the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad to the east, with both options ending in Fairbanks. There were also reconnaissance trips to the Iditarod and Kuskokwim areas, and a study of the potential for tunneling through the mountains at an old portage point at the head of Turnagain Arm to access an ice-free port at the head of Passage Canal.

The “City of Tents” on Ship Creek, 1915. Businesses include White Road House.

[Marie Silverman papers, Archives and Special Collections, Consortium Library, University of Alaska Anchorage]

Edes and Mears both recognized the great potential of the Ship Creek site at the head of Cook Inlet, being close to the coal fields at Matanuska, and having thousands of acres of eminently developable land, wooded in valuable birch and spruce, adjacent to a port which would be open for at least six months of the year.

In April, 1914 President Wilson announced his decision, selecting the western or Susitna route, beginning at Seward and including purchase of the Alaska Northern Railway, proceeding northward around Cook Inlet, across the Matanuska and Susitna Valleys, through the Alaska Range at Broad Pass, and crossing the Tanana River to end in Fairbanks.

Tents and buildings next to Alaska Railroad track at Wasilla, May 4, 1917.

[Alaska Engineering Commission photo by Phinney S. Hunt]

Sixteen days after the president signed the order, Commission Chairman Edes - now Chief Engineer for the project - had selected Seward as his headquarters for railroad operations, Lt. Mears was landing men and supplies on the banks of Ship Creek, and Thomas Riggs had gone north to take charge of the survey parties working from Broad Pass to Fairbanks.

In support of their efforts to get underway with the building of the railroad, tremendous mountains of supplies and materials were being shipped to Alaska, and small armies of men were gathering.

Anchorage dock, November, 1919.

A.E.C. photo

The railroad route was split into three divisions, the Seward Division, Anchorage Division, and Fairbanks Division, and each Division was broken down into Districts.

There were official efforts to prevent a stampede to the railroad construction center at Ship Creek, but when Frederick Mears arrived on April 26, 1915, he was greeted by a city of white tents which stretched along both banks of the creek, right where he intended to built his railroad construction camp and the main terminal. Undaunted, Mears set to work, and the ceremonial first spike was driven three days after he arrived.

A 350-acre site on the plateau south of Ship Creek was platted just as railroad towns in the American West had been, in a neat grid of streets running north-south (named alphabetically) and east-west (named numerically), with the notable exception of Christiansen Road, which cut a long angle up the steep bluff from the creek. The townsite developers reserved lands designated for a school, a cemetery, parks, federal buildings, and for Indian possessions, and the city of Anchorage became the first of several towns the U.S. government would survey and build in conjunction with the railroad construction. ‘

Trail above Turnagain Arm, February, 1917.

A.E.C. photo

Equipment and materials used in building the Panama Canal were transported north on freighters and used in building the Alaska Railroad, including four locomotives, two steam shovels, 15 flatcars, a large dredger, and thousands of tons of materials and machinery.

The first order of construction was to reach the coal fields along the Matanuska River at Sutton and Chickaloon, and before the summer was out thirteen miles of steel rail had been laid in that direction, to the high trestle and bridge which crossed the glacial Eagle River. By the end of summer, 1914, another 35 miles, across Peters Creek and the Eklutna River and arcing around the head of Knik Arm, had been cleared and graded, ready for work in the spring, and an additional 40 miles across the broad Matanuska Valley had been cleared of brush and timber.

To the south, Commissioner Edes was overseeing repairs to the Alaska Northern Railway from Seward to mile 72. Because the U.S. government was only leasing the railway, pending settlement of grievances between the litigious American and Canadian bondholders, Commissioner Edes ordered that only the necessary work be done to make the tracks safe for use by gas-powered railcars. Edes would later tell Secretary Lane that the Alaska Northern was in worse shape than they had first thought, and that bridge and tunnel timbers which appeared sound were riddled with rot. Even with the repairs, during the winter of 1915-1916, until April 25, the mail, freight, passengers and other traffic which would have traveled by train was carried by dog teams along the railroad route between milepost 35 and Anchorage.

Between Potter Creek and Rabbit Creek, Mile 104 near Potter, July, 1917.

[P.S. Hunt photo]

To the north, Commissioner Thomas Riggs and his engineers were surveying the route through the Alaska Range toward Fairbanks. The locating surveys of 1914 had shown the general route, but now the line needed detailed surveys and the final locations marked on the ground for the construction groups who followed.

With horses packing their equipment and supplies across the wilderness, the survey parties slept in tents or just on the ground at night, cooking over campfires and fighting hordes of mosquitos as they slowly made their way north. To assist in river travel and moving supplies and equipment, and to avoid the increasingly high prices charged by private carriers, the Alaskan Engineering Commission arranged for the construction of a 50- foot sternwheeler, the Matanuska, which plied the waters of the Susitna River and its tributaries.

The work of building bridges, trestles, laying ties and extending the rails over them was paid by the hour, which in 1915 was reported to be thirty-seven and a half cents an hour for laborers. Skilled carpenters could expect forty to sixty cents an hour. In his book, 'Railroad in the Clouds' (Pruett Publishing Co., 1977), railroad historian William H. Wilson drew an especially poignant portrait: “Fading gray photographs capture the dull sameness of their daily lives. The laborers stand against a boreal background, usually stiff and unsmiling under broad-brimmed hats. Wide galluses over rough shirts, denims tucked into heavy boots, were the working clothes of the men whose toil built the railroad.”

On May 26, 1916, the surveyors and engineers working under Commissioner Thomas Riggs in the Fairbanks Division reached the wide Tanana River at a point 70 miles downstream from Fairbanks. Here a Native village sat alongside the river, just east of its juncture with the smaller Nenana River. The government workmen built a wharf and erected a few frame and log buildings, including a main office and a large two-story commissary, and set up a hospital in two great white tents. They then set about platting a townsite for Nenana, and lots would be auctioned to the highest bidders, just as they had previously been auctioned for Anchorage, Matanuska, Wasilla, and Talkeetna.

Reaching navigational waters at Nenana meant supplies and materials could be shipped via steamboat and stockpiled until needed, and the vessels of the Northern Commercial Company brought cargo along the Yukon and Tanana Rivers, from the west via St. Michaels, and from the east via Whitehorse. Overland, the best time for transportation was in winter, when the land was frozen, and freight teams of horses could move wagonloads of equipment, materials and supplies.

The narrow gauge Tanana Valley Railroad, which ran from Chena to the gold fields at Chatanika, was purchased by the federal government in 1917 for $300,000, providing a head start on the rail line south to Nenana. Historian William H. Wilson explained the details in his well-written account of the times, Railroad in the Clouds: The Alaska Railroad in the Age of Steam (Pruett Publishing, 1977): “By buying the destitute little line, the Commission reduced its own rail charges from Chena and gained the first leg of a narrow gauge link with Nenana, where coal from the lignite fields could be rushed to Fairbanks’ fuel-starved mines.

Alaskan Engineering Camp No. 88, Turnagain District, 1917.

[A.E.C. photo]

In April, 1917, the United States entered the First World War. The major powers of Europe had already been fighting for three years, but President Wilson had kept the U. S. neutral as he worked to find a peaceable solution to the bitter conflict. Finding none, he reluctantly declared war against Kaiser Wilhelm’s German forces.

Although far removed from Alaska, the war would have a devastating and long-lasting effect on the railroad effort, especially in Fairbanks. Judge Cecil Clegg declared the war set Fairbanks back ten years by draining the area of its young, capable workforce and thereby slowing construction of the railroad.

Laying track at Matanuska, 1916.

A.E.C. photo

In the Anchorage Division, AEC Commissioner Frederick Mears received a promotion to the rank of Major from the War Department, and upon returning to active duty he was given orders to recruit, train and equip 1,000 men for the construction and operation of military railroad lines in France.

Mears gained permission from Secretary Lane to solicit men from the Alaskan Engineering Commission for his regiment, and the response was a hearty one. Between the men joining Mears and those leaving for more lucrative wartime work in the States, the railroad’s work force was decimated by half. Work continued on the railroad, but the average monthly number of employees dropped from 4,466 in 1917 to 2,550 in 1918.

On September 10, 1918, the only remaining gap in the rails between Seward and Anchorage was closed when the last rails were laid and, at a formal ceremony marking the event, Commission Chairman William C. Edes drove the final spike.

To the north, the end of track reached mile 373, just south of Nenana, by January, 1919, but little work was done on the railroad until late summer due to a lack of appropriation from Congress. By the end of the year there was still a gap of 122 miles between the Anchorage and Fairbanks divisions. In August, 1919, shortly after returning from his wartime duties and assuming the position vacated by Commissioner Edes, that of AEC Chairman and Chief Engineer, Col. Frederick Mears issued a reorganization order which consolidated the administration of the government railroad into one functional operation, with headquarters at Anchorage.

Tanana River bridge under construction, Nenana, Mile 411.7, October 27, 1922.

A.E.C. photo

The Hurricane Gulch bridge was, according to many sources, one of the most difficult construction projects involved in the building of the railroad. At 918 feet in length and soaring 296 feet above Hurricane Creek, a tributary of the Chulitna River, it was the longest and highest span built, and an engineering marvel. It was one of the few construction projects given to an outside contracting firm, the American Bridge Company, of Gary, Indiana. Actual construction would be started in March, 1921, and completed on August 15, 1921. By 1921 two unfinished bridges, at Riley Creek, Milepost 347, and over the Tanana River between Mileposts 411.7 and 413.7, were all that prevented steel rail from meeting between Seward and Fairbanks.

In June, 1923, the twenty-ninth President of the United States, Warren G. Harding, and his wife, Florence, set out on an epic journey, to cross the country to Seattle and then go north to Alaska and take the much-touted Great Circle Tour, stopping in Nenana to drive the Golden Spike to signal completion of the Government Railroad.

At Seward, the Presidential party, including 23 government officials, their wives, 32 press members and 30 railroadmen, boarded the train, making the first stop in Anchorage, where they received an enthusiastic welcome.

Tanana River bridge at Nenana, Mile 411.7, January 5, 1923.

A.E.C. photo

They spent three hours in Anchorage before boarding the train again for the journey north. At the Wasilla stop, President Harding took the throttle of Engine 618 and gleefully drove the train 26 miles, to the Willow station. The Presidential party spent that evening at Curry, and the next morning ‘Alaska Nellie’ Neal served heaping plates of sourdough pancakes in her warm roadhouse kitchen, commenting, “Presidents of the United States like to be comfortable when they eat, just like anyone else!”

President Warren G. and Mrs. Harding, 1923.

The following day, July 15, 1923, President Harding drove the golden spike in a formal ceremony, marking the completion of the Alaska Railroad and dedicating the Government transportation system to public service. After 21 years and an estimated cost of $60 million, the ocean ports of the North Pacific were connected with the navigable waters of interior Alaska by two narrow bands of steel.

The Alaska Railroad, owned by the State of Alaska since 1985, winds four hundred and seventy miles through the very center of The Great Land, from the coastal waters at Seward to the Golden Heart of the state at Fairbanks. Along the route the terrain is constantly changing, from climbing through the beautiful Kenai Mountains to edging along the tidewaters of Turnagain Arm, then wending through the Anchorage bowl and the Matanuska and Susitna Valleys, and crossing the formidable Alaska Range just east of Denali—the Great One.

Regularly scheduled service provides transportation for almost half a million passengers every year, and the Alaska Railroad’s scenic routes, such as the Coastal Classic, the Denali Star, and the Glacier Discovery, are popular travel options for tourists—and for residents seeking to share Alaska’s unequalled beauty with family and friends.

Perhaps the most unique feature of today’s Alaska Railroad is the flag-stop service on the Hurricane Turn, north of Talkeetna. One of the last flag-stop railroad routes in the United States, this service provides invaluable transportation for residents of the roadless area between Talkeetna and Hurricane, where the railroad meets the Parks Highway just before crossing Hurricane Gulch. Passengers can flag down the train anywhere along this route by waving a large white flag or cloth, and the option is popular with hikers, hunters, fishermen, weekend cabin owners, and especially those who live along the route and depend on the train to obtain food and supplies.

Hurricane Gulch, July 21, 1921.

A.E.C. photo

The railroad has a vital role in transporting Alaska’s natural resources such as oil, coal, and gravel, hauling over five million tons of freight each year, and the Alaska Rail-Marine Service between Whittier and Seattle ensures seamless travel between Alaska and the lower 48 with a fleet of rail container vessels. The hardy pioneer workmen who built The Alaska Railroad one hundred years ago could not have imagined the speed and luxury with which today’s travelers can cross the state, but today’s travelers likewise can scarcely imagine what it must have been like for those stout-hearted souls who braved the elements to build the railroad.

Whether we utilize the railroad today for business, pleasure, transportation, or simply pause alongside the tracks and thrill to the thunderous passing of those gold-and-blue cars, we owe a nod of gratitude to the far-sighted builders of The Alaska Railroad. We are all immeasurably richer for the great treasure they gave us. ~•~

[From the book, The Alaska Railroad 1902-1923, by Helen Hegener. Northern Light Media, 2018.]