Vol. XXXVI, No.1

March 2019

FOUNDED IN 1937 BY THE VOLUNTEERS OF THE LINCOLN BRIGADE. PUBLISHED BY THE ABRAHAM LINCOLN BRIGADE ARCHIVES (ALBA)

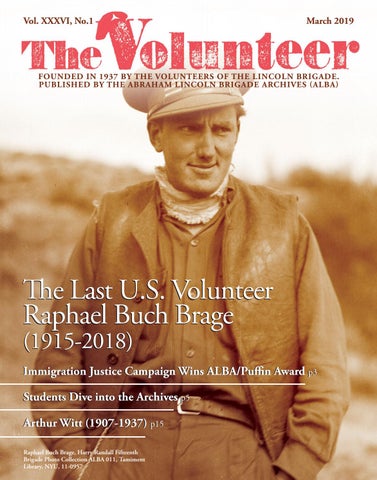

The Last U.S. Volunteer Raphael Buch Brage (1915-2018)

Immigration Justice Campaign Wins ALBA/Puffin Award p3 Students Dive into the Archives p5 Arthur Witt (1907-1937) p15 Raphael Buch Brage, Harry Randall Fifteenth Brigade Photo Collection ALBA 011, Tamiment Library, NYU, 11-0957