Table of Contents

Jefferson Island Education Center

Placed on the site of a 1980 mining disaster in New Iberia, LA, this project seeks to inform visitors on the uniqueness of Jefferson Island and the mining disaster through the museum experience and its design.

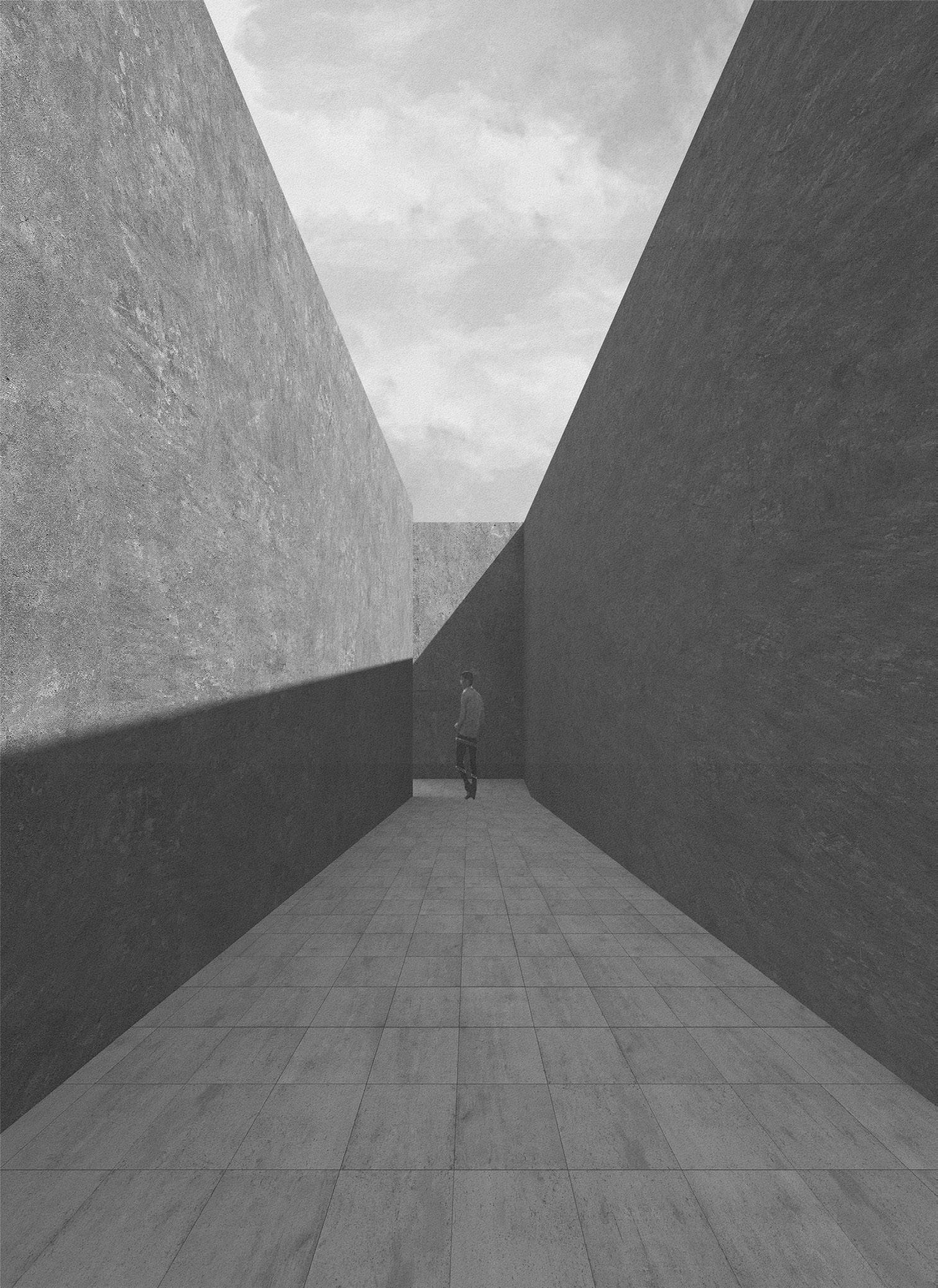

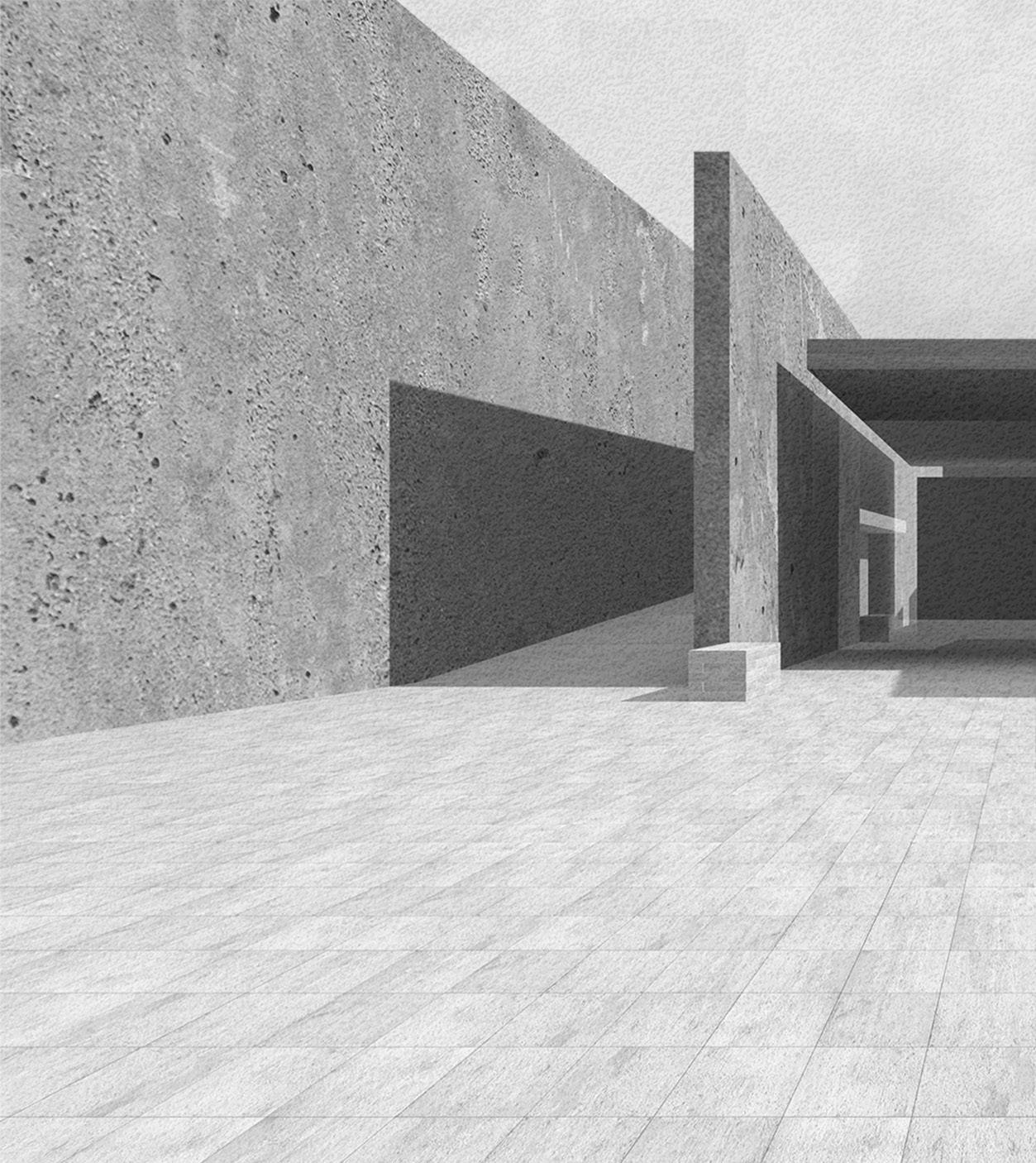

The entry sequence of the museum is situated on the above-ground footprint of the former mining operations. Arriving on to an expansive plaza memorializing the former mine building, visitors to get a sense of the scale of the mining operations, before descending into experience, walking along a retaing wall marking the datum between built and natural environment.

Visitors will circulate between a system of retaining walls that slowly disintegrate towards the water line, opening up at the end of the experience. These retaining walls dictate every aspect of the experience, from

circulation to light permeation, and even interior vs. exterior space. As visitors descend, they are greeted by the first of three interior spaces - the lobby - all of which are slotted between the retaining walls, and enclosed with glass planes on the ends. This allows the interior and exterior to blend, eliminating the presence of a threshold As they exit the lobby, they once again go outside to ramp down to the main gallery and video room.

After going through the gallery, visitors descend through the walls one final time, bringing them to the social terrace, cafe and reading room. As the visitors near the end of their experience, the terrace opens up, allowing for views to the lake through the disintegrating walls.

Ramping down into the experience

Above: Inside the lobby

Below: Section A-A

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

The Big Shift

A collective housing project

The bank of the Mississippi in New Orleans is, put simply, a controversial area. What was at one point the main connector of industry and goods has fallen into disrepair. However, with climate change threatening the entire New Orleans area, city officials have started planning a major shift in the city. Moving the port to a less central location, allowing the river bank to be revitalized as a park, simultaneously protecting the city environmentally and financially.

This housing block is a space that fosters community growth, through an open, permeable ground floor with community rooms, a local restaurant, and a covered market facing the new commercial corridor of Tchoupitoulas St. The patio culture of the South is extended to these apartments, with patios punching holes into the facades of the buildings, even in the stairs. This openness allows residents to interact with eachother, and with the community on the ground, creating a sustainably minded community geared towards contributing to the changing scop of New Orleans.

Top: Approaching the market from Tchoupitoulas Street

Top: Approaching the market from Tchoupitoulas Street

On the housing levels, each apartment is divided into a series of rooms starting at 9’x12’, slotting between the bearing walls. The homes start to break the divisions in bigger units, acting like tetris blocks sliding into place.

Top: Typical Unit plans

Bottom: From the inside looking out

The Sectional Home

The culmination of a 4 week housing exploration, this single family home brings 3 generations together through designed diagonal views an integrated patios.

Tasked with the challenge of creating a ‘mushroom’ shaped home for a 3 generation family, this home only has a footprint of 240ft2 but expands in the above levels to accomade the necessities of the family.

A series of identical rectangular volumes, all shifting on different axes create the ‘mushroom’ condition, while also opening up patio access throughout the house. Repeating these identical volumes throughout the house allows for the interior to be carved out in section, creating interior balconies, and giving the family an oportunity to interact between levels.

In such a vertically oriented house, the stair cannot be treated solely as a mode of vertical circulation; it must function as a connector, bringing the family together across floors. To inspire this interaciton, the stair is oriented around the primary public spaces - the patios. Doing this also incorporates the stair as a part of the home rather than a separate aspect, placed in like an afterthought.

How can dynamic views be created through the aggregation of a single volume?

Combining volumes and carving out redundant space creates more private interior balconies, introducing a spatial relationship in section, while moving the public spaces to the outdoor stairs and patios

The Inhabited Stair

A short design excercise further exploring the idea of the stair as a programmed public space, an inhabitable connector.

Created as an oasis, this stair serves more as a stepped garden than a conventional stair. Visitors ascend up to the top of the structure before making their way down to the main pool, meandering with streams of water that define the circulation as it flows into the main pool.

Incorporating the stair into the primary structure, and even letting it take over and become the focal point allows this oasispark to become a multilevelled stepwell, and creates different secluded pockets within it to socialize and sit.

Room with a View

A one room artists-studio for Photographer Charles Gaines, designed around one taskframe a view. In this case, the view is one of Gaines’ most famous photographs, Walnut Tree Orchard Set D.

Situated in the orchard of this famous photograph, this studio aims to hide and fake the view as much as possible, before finally opening up and revealing the carefully composed view. Greeted by an enclosed tree, visitors of the studio immediately understand that the room is meant to show off the orchard, and the view. As visitors are compressed through the entryway, they see other works by Gaines, and getting glimpses of the other trees outside. As carefully placed light bars lead them through the hall into the room, they ramp down slightly, lowering to the correct eye-height to properly take in the view.

Finally, when the space opens up into the room, visitors are greeted by the view, along with Gaines’ workspace. Upon exiting the studio, visitors enter on to an outdoor courtyard, inset into the ground at floor level, that encloses another tree, truly allowing the orchard to take precedent over the studio, and easing visitors back into their surroundings, just as they were eased into the space.

Site plan showing the location of the studio, highlighting the fireld of view

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

Site plan showing the location of the studio, highlighting the fireld of view

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

Sections, showing different conditions between the entry, the room, and the exit

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

Sections, showing different conditions between the entry, the room, and the exit

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

Top: Perspective inside the room

Top: Perspective inside the room

The Horizontal House

A 1200 sq. ft. patio home for a 3 generation family of 5. The first part of a 4 week housing exploration.

With today’s increasing population and decreasing land area, high density housing is becoming more necessary, both as a real-world condition, and as a pedagogical tool. The ability to design small homes for families while maintaining the privacy and quality of life that comes with a larger home is becoming extremely important.

This home was designed from the inside out with the needs of the family taking precedent over the design. Constrained to only 900 sq. ft. of living space and 300 sq. ft. of patio space (1200 sq. ft. total), this home explores how a space shift and slide to create privacy.

Based around a 9 square grid, this home slides sections of the grid to create private wings, while breaking down the walls between squares to create spacious public areas with a smooth flow. The outdoor spaces occupy the voids created by these shifts, creating natural light within the 1200 sq. ft. square

The Vertical House

A tower home with a 240ft. sq. footprint housing a group of 5 students. The second part of a 4 week housing exploration.

High density housing in an urban context is an increasingly important aspect of housing design. Building up rather than out becomes necessary when land is at a premium, but with this comes challenges, most notably, creating a sense of community and fostering interpersonal interaction in such a separated home.

In such a tight space as this, the main form of circulation - the stair - is forced into a central position of the design. This called for a rethinking of the stair’s role, turning it into the primary public space, with the landings stemming off to create rooms, as opposed to the rooms stemming off to the stairs.

Using a switchback stair maximizes the centrality of the stair while promoting a cross-level interaction. In this way, the stair can divide program with more private rooms on one side and more public rooms on the other, while still keeping all the roommates connected.

Tulane Depot

A multipurpose space for research, display and archival storage consolidating all of Tulane University’s collections.

Placed on the abandonded Piety Wharf in New Orleans, LA, this is a multipurpose space full of constraints. The space has to hold ample archival materials, multiple research rooms, offices for researches, and display selected artifacts from Tulane University’s 7 collections - all in a 100’x100’ area. In order to fit all of this programming, circulation and hierarchy are key.

Visitors will wind through the rows upon rows of archival material, being able to pick up and further examine anything that interests them. As they walk through, selected displayed artifacts, along with selectively placed apertures, will guide visitors through the circulation, eventually leading to the main exhibit space.

Hidden upon entry by the research offices, the main exhibit space is both rotated and slightly raised, allowing visitors to truly separate this special space from the rest of the Tulane Depot. Though there are subtle hints along the circulation path, this special moment is hidden as much as possible to surprise and attract visitors into this larger, rotated space.

Plan Mashup

Precedents: Casa Malaparte, Adalberto Libera; Villa and Pavilion, Aldo Rossi; House in a Plum Grove, Kazuyo Sejima; House With A Void, Studio Sean Canty; Brick Country House, Mies Van Der Rohe

Orthographic drawings (plans, sections, elevations) all have one inherent weakness: they can never be true to the essence of their subject. No matter how faithfully or accurately drawn, orthographic drawings fail because, in the end, they are two-dimensional representations of a three dimensional object.

The failure to holistically represent architecture in orthographic projection creates a departure from reality. One that makes orthographic drawings into separate, illusive drawigs, highlighting space and inclosure above all else. Their use in architecture comes with their legibility and delivery of these conditions.

In this exercise, plans were used as independent objects, and as tools for ordering parts. Different precedent plans were chosen, drawn, and combined to create a new space showcasing a new condition: Plan with Courtyards.

The Plan Mashup with surrounding imagined land, creating a plan with courtyards

Bird’s Eye Axonometric: The Monastery

The Monestary - 1/16" = 1'-0"

Alex Cohen

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

Alex Cohen

Portfolio | Alex Cohen

The Monastery

Bird’s Eye Axonometric

Axonometric drawings are the most comprehensive types of paraline drawings. That is, all drawings projected into 3 dimensions on paper using parallel projectors perpendicular to the picture plane. In all types of axonometric projection, one of the three axes is drawn to scale. This preservation of scale, along with their ability to show all 3 dimensions makes axonometric drawings extremely useful for displaying information, both technical and pictorial.

Inspired by the graphic representation techniques of a precedent drawing (Iffy Prints, Chibbernoonie), this drawing continues to build on the decisions made in the Plan Pattern, creating the idea of an imaginary monastery, focusing on methods of representing depth, material, and plane (horizontal and vertical) change.

Boom!

Artistic Reimagining of Piazza D’italia

Designed by the famous postmodern architect Charles Moore, and initially completed in 1978, Piazza d’Italia is a symbol of 2 things: The postmodern ethos, and Southern deterioration. Upon completion, this plaza, intended to be a “surprise” plaza in the rapidly developing downtown New Orleans, was deemed a postmodern masterpiece and recieved widespread acclaim. However, the plaza fell into disrepair and obscurity as the downtown area developed without the intended surroundings of the plaza, becoming an unfortunate symbol of development in New Orlearns - deteriorating and often unfinished.

Directly translated, Gesamptunstwerk means ‘total work of art.’ Semantically, this definition gives the essence of this drawing: re-present and reimagine Piazza d’Italia as one illustration, using the site as a place for speculation and meditation on a new identity.

Tapping into the inherently unique traits of postmodern architecture, and using Bernard Tschumi’s depiction of his seminal works of postmodern architecture, this drawing captures the rarity and quirkiness of a place like Piazza d’Italia. Exploding the individual pieces of the plaza into space allows us to appreciate Piazza d’Italia for its extremely one-of-a-kind architecture, rather than focusing on the poor physical condition it holds today.

Top 3: Photos of Piazza d’Italia

Top 3: Photos of Piazza d’Italia

Boom! Alex Cohen

Boom! Alex Cohen