10 minute read

D R A W I N G III 32

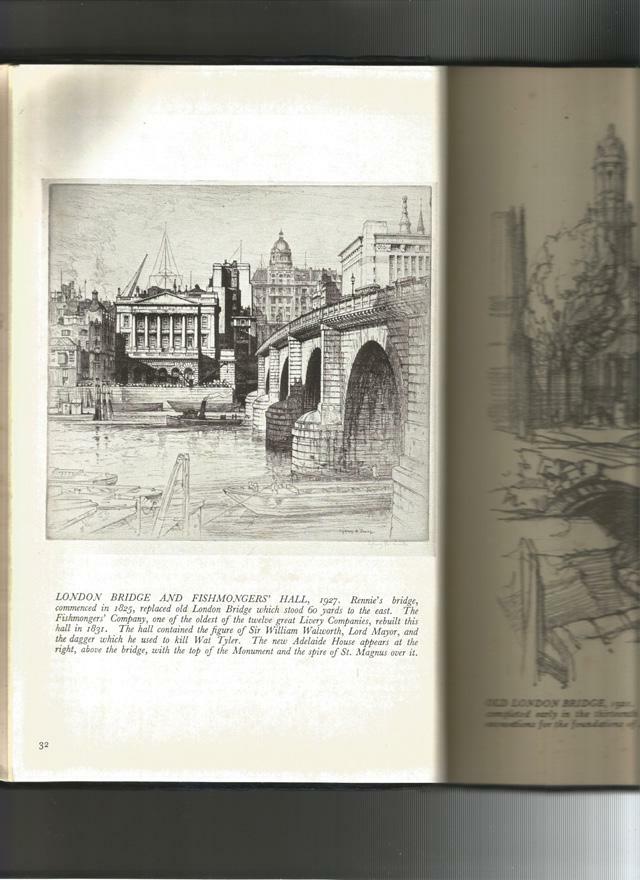

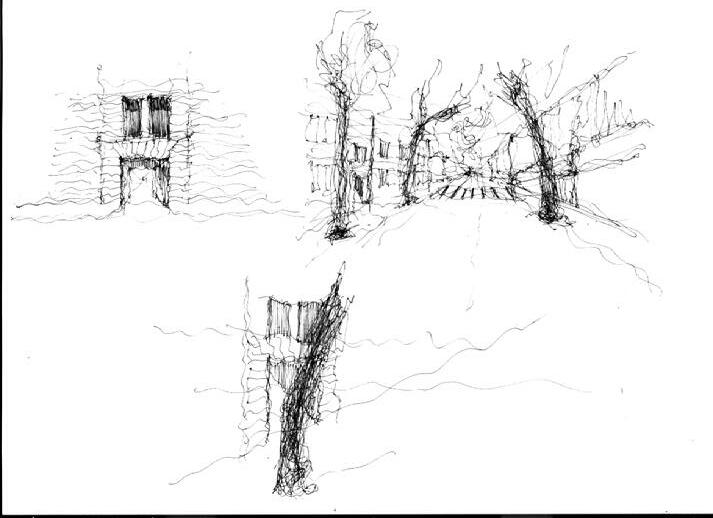

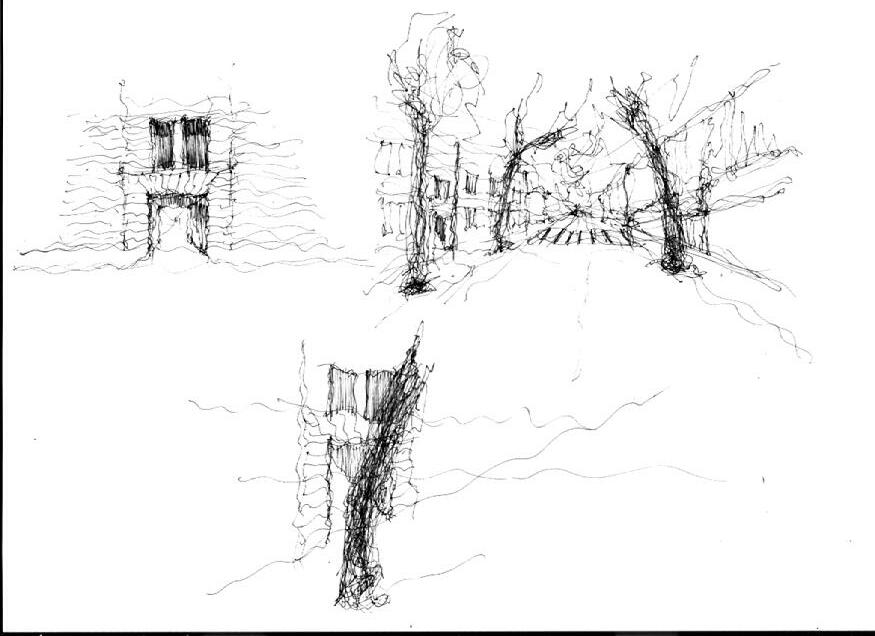

Figure 11: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

other element is the focal point which represents a signifying edifice that acts as a point in space to travel to.

Advertisement

The drawing appears candid, however, it also feels like it depicts a median between the two points of serial vision and focal point. Serial vision can be understood as the phenomenon of transitioning through space and it is represented by the series of images that are gradually revealed.21 The focal point is suggested by the skyline within the picture, it is usually indicated by a tall vertical element symbolizing a place of congregation.22 The fact that the detail of the drawing is in the distance is suggestive of both of these points. Due to the fact the drawing is unfinished, the detail is further enough in the distance (smaller on the page) to require more information for a full image. Despite it having the ingredients to communicate the overarching narrative of the picturesque city, a place inspiring fondness, it leaves it lacking information that would otherwise communicate an accurate picture of the place.

Based upon the principles of the picturesque discussed relating to ‘pictures’ I conclude that LT makes a successful account of London in a picturesque way. S.R.J uses archetypal tools to convey charming moments such as the framed entrance onto Lower Regent Street. Potentially dank and intimidating spaces are conveyed in a charming way through the use of clair-obscur as explored when analysing his drawing of Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C and the fact that London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall was less successful than other drawings at the use of tools of the picturesque, is not necessarily a bad thing as it forms part of the visual variety required for the picturesque.

C H A P T E R I E N D - N O T E S

11 J. Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 22

12 William Gilpin, Three Essays: on Picturesque Beauty; on Picturesque Travel; and on Sketching Landscape, London, Printed for R. Blamire, 1792, p.42-46

13 Sydney R. Jones, London triumphant, London, Studio Publications, 1942, p.50-51

14 E. H. Gombrich, ‘The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape’, in Norm and Form, London, Phaidon, 1966, p.123-126

15 Marc Auge, non-places introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity, John Howe, London, Verso, 1995, p.77

16 Lexico Dictionary, coup d’œil definition, https://www.lexico.com/definition/coup_d’%C5%93il

17 J. Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 23

18 Ibid., p. 23

19 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 21

20 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, op. cit., p. 23

21 Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Arhitectural Press, 1961, p. 9

22 Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Arhitectural Press, 1961, p. 26

23 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities,

C H A P T E R I P I C TU R E S

Figure 1: London Triumphant, List of drawings by Author, 2022. Figure 2: London Triumphant, Chapter locations by Author, 2022. Figure 3: Chaper I Location Map by Author, 2022. Figure 4: Old London Bridge by Sydney R. Jones, 1921. Figure 5: Lower Regent Street Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022. Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928. Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022. Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927. Figure 9: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C Historical Map (19241951) by Author, 2022. Figure 10: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall, Historical Map (1924-1951) by Author, 2022. Figure 11: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall (1924-1951) by Sydney R. Jones, 2022.

IV

VIII

V

1:5000

100m 0 100m 200m 300m 400m 500m

C H A P T E R II

I R R E G U L A R I T Y

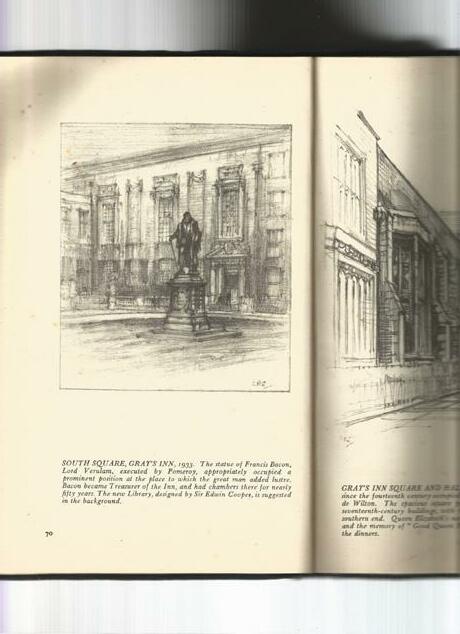

D R A W I N G IV

D R A W I N G V

D R A W I N G VI

The main contradiction of the picturesque is that the process of achieving that which is picturesque is actually dependent not on pictures, that is to say how a place looks but on how buildings/ streets are laid out, which in turn influences how things come into view within the space.22

For clarity, it is important to define that S.R.J’s drawings, being 2d pictures that illustrate 3d space, rely on an understanding of what is happening within the plan of the space being illustrated in order to have an accurate representation that is picturesque. According to Nikolaus Pevsner, irregularity within the plan is what is needed for this as this is what actually dictates the representation of the picturesque scene. This suggests that the picturesque is an experiential phenomenon and not an observational one.23 So again, by representing London in this manner he reminds the viewers that it would not be possible for them to experience London as picturesque if it is not preserved. Since picturesque architecture is a phenomenal experience that is not purely about observation, John Macarthur states that its formal description is not possible as the experience requires a progression through space with a series of varying still pictures, where factors such as sequence and duration are relevant.24 However, around the 1940s, a process called townscape had begun which can be seen as the of old picturesque ideas that sought to implement the principles of the picturesque in order to plan the city’s landscape. Qualities that are similar to those promoted by Townscape can be found in the work of nineteenth-century Austrian architect, Camillo Sitte.

In Camillo Sitte’s book, City Planning according to Artistic Principles, each chapter is arranged into various principles that address the city in a different way. S.R.J’s drawings will be described and analysed in accordance with these principles in order to understand if these principles create irregularity within his work and whether his drawings can be considered to be picturesque.

Figure 13: narrow streets in The City of London by Author, 2021.

It is variety within the picturesque that stimulates visual pleasure and creates aesthetic value, and this is inextricably connected to irregularity within the planning and layout of buildings, public squares, plazas, monuments and streets. Bold buildings are typically located around a plaza with monuments in the centre that could be celebrated. This principle is described as having unifying qualities that draw people to its centre. 25 As was mentioned earlier, the oldest areas containing monuments are usually the most irregular in form26 and views with monuments in them are most aesthetically pleasing when they are placed on the periphery of a plaza.27 Plazas and squares are designed to be experienced from their longest length in order to increase their dramatic effect and enclosing them preserves the character of the space. Additionally, irregular plans create views that are aesthetically pleasing as they appear organic, a subjective point of view from Camillo Sitte, nevertheless is suggested by Figure 13. Images of the winding streets of The City of London and the vistas created from the free-flowing streets. Plaza groupings within old towns frequently consisted of multiple places conjoined to form one, this phenomenon was widely done in order to create the ideal view of a prominent building within the plaza. Essentially, the chosen elevation dictated the layout of the plaza.28

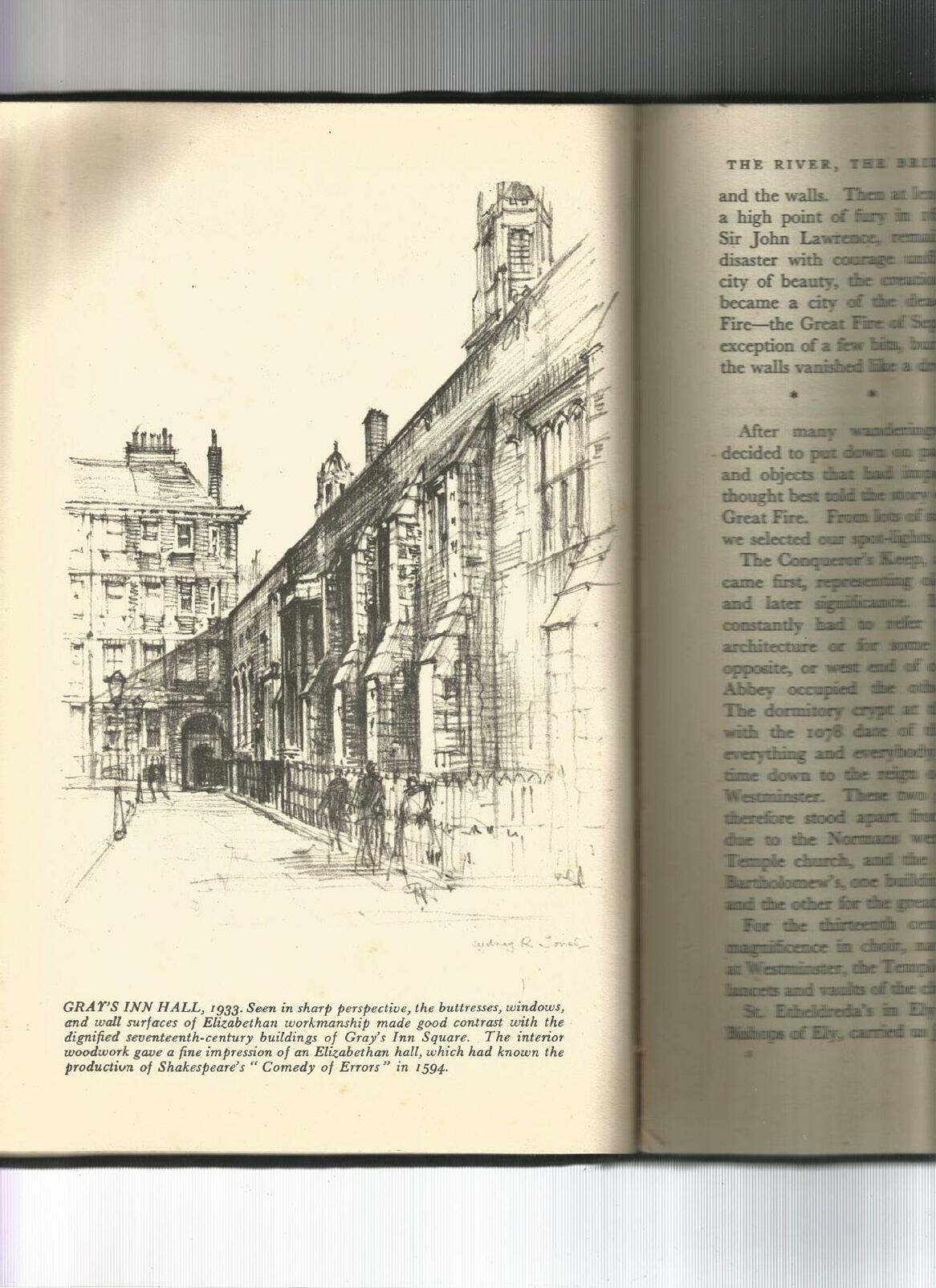

D R A W I N G IV

Gray’s Inn Hall, pictured on the next page, shows the “sharp perspective”29 of the buttressed windows and the view is indicated on the plan of the square. The Gestures of figures are roughly sketched in the foreground with the elevation of one of the periphery buildings in the background, where the perspective is guiding the viewer. An entrance to the square is suggested to the right of the drawing that is drawn in loose linework and legal buildings form a perimeter around the square with Gray’s Inn Hall, the most prominent building toward the South. According to Camillo Sitte, the forum, agora and public square served to frame public life,30 in the case of Gray’s Inn the square serves 1, as a transitional space and 2. as a place for lawyers occupying the periphery buildings to take lunch. The drawing captures the South pavement along with the elevation of Gray’s Inn and the street reflects the quiet nature of the ‘private’ square that is used primarily as a place to stroll through. However, a hallmark of the square that made it picturesque was its ability to frame and facilitate public activity. In the picturesque, some artists use a tool called appropriation to inhabit the scene, conforming to the picturesque standard of having a space

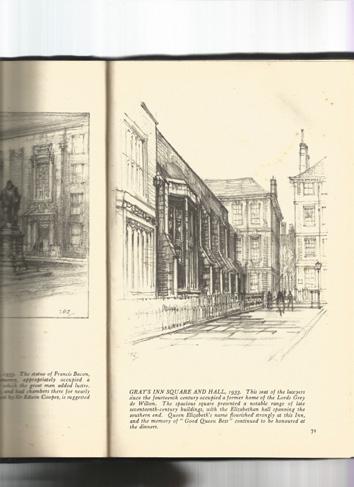

(Above) Figure 14: Gray’s Inn Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933. (Bottom left) Figure 15: Gray’s Inn Square and Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933. (Bottom right) Figure 16: South Square Gray’s Inn by Sydney R. Jones ,1933.

Figure 18

Figure 14

D

Figure 19

C

B

A

1:1000

20m 0 20m 40m 60m 80m N

100m

(Top - Bottom) Figure 18: Sequential Images depiting approach to Gray’s Inn Hall, from Northern entrance by Author, 2021.

A

B

C

D

filled with life and activity,31 however, S.R.J chooses to articulate the true nature of the space accurately as a quiet space opposed to contriving what was not there.

Four archways frame entrances into the square along each perimeter, as indicated on the plan and photos, they intersect the periphery elevations creating tunnels into the square. This way there is no clear sightline outside of the square or any other entrance, allowing for a continuous elevation and unbroken sense of the character of the square. This artifice was taken from old city planning and was seen to create picturesque settings by allowing each square to retain its own character. The drawing of Gray’s Inn Hall is successful in suggesting the experience of the square’s turbine plan layout, where only one entrance is visible from a viewpoint. Although no entrances are directly visible in the picture, the layout and material context is implied. Within the picture, no monuments are visible, despite the monument of Francis Bacon Figure 16 being visible on the plan. Consequently, the view although dynamic due to the buttressed elevation of Gray’s Inn, lacks the excitement that Camillo Sitte describes when monuments are placed along the periphery of a square.

Camillo Sitte states that there are two types of a city square, deep vs wide, which are defined by the person’s position within the square and the direction of their sight in relation to the major building within the square.32 What is interesting about Gray’s inn Hall, the square is experienced from its four sides and from each entrance. The most dramatic of these is the entrance entering from the North that looks towards Gray’s Inn Hall, as the elevation of the hall offers the most dynamic façade of all the elevations and the entrance looks directly at the elevation. The second is from the entrance from the West that looks across the elevation of Gray’s Inn. As Visible in Figure 14, the buttresses that are captured in the sketch perspective are dynamic and add presence to the scene. Finally, the arrangement of the plan layout of the square itself is quite regular being a rectangle, however, the approach to the square from the neighbouring entrances can be seen to be irregular as the states of enclosure vary from narrow settings to open and the approach to the square is not necessarily linear either. The approach from the East guides you towards the large external façade that has one small irregularity at its base which is the entrance to the square and although it is a linear approach, what the viewer encounters visually is a variety of views, each different from the last Figure 19. This effect when experienced