L I S T OF I L L U S T R A T I O N S

C H A P T E R I P I C TU R E S

Figure 1: London Triumphant, List of drawings by Author, 2022.

Figure 2: London Triumphant, Chapter locations by Author, 2022.

Figure 3: Chaper I Location Map by Author, 2022.

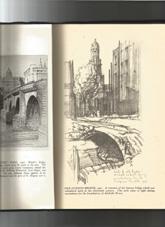

Figure 4: Old London Bridge by Sydney R. Jones, 1921.

Figure 5: Lower Regent Street Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928.

Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022.

Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

Figure 9: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C Historical Map (19241951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 10: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall, Historical Map (1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 11: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall (1924-1951) by Sydney R. Jones, 2022.

C H A P T E R II I R R E G U L A R I T Y

Figure 12: Chaper II Location Map by Author, 2022.

Figure 13: Narrow streets in The City of London by Author, 2021.

Figure 14: Gray’s Inn Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933.

Figure 15: Gray’s Inn Square and Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933.

Figure 16: South Square Gray’s Inn by Sydney R. Jones ,1933.

Figure 17: Gray’s Inn Hall, Historic Map(1924-1951).

Figure 18: Images depiting approach to Gray’s Inn Hall, from Northern entrance by Author, 2021.

Figure 19: Diagrams illustrating approach to Gray’s Inn Square from West by Author, 2022.

Figure 20: Gray’s Inn Hall, Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 21: New Court from Fountain Court, Middle Temple, 1930.

Figure 22: Lombard Street by Sydney R. Jones, 1922.

Figure 23: Lombard Street Historical Map by Author, (1924-1951), 2022.

C H A P T E R III: M O V E M E N T

Figure 24: Chaper III Location Map by Author, 2022

Figure 25: Lloyds Leadenhall street Historical Map by Author, (1924-1951), 2022.

Figure 26: Lloyds Leadenhall street by Sydney R. Jones, 1928.

Figure 30: London Triumphant, Pictures, Irregularity, Movement, by Author, 2022.

Figure 27: Bush House, Strand by Sydney R. Jone, 1931.

Figure 28: Bush House, Strand Historical Map by Author(1924-1951), 2022.

Figure 29: The Institution of Civil Engineers, Great George Street, Westminster by Sydney R. Jones, 1936.

Figure 30: The Institution of Civil Engineers, Great George Street, Westminster by Sydney R. Jones, 1936.

Figure 31: London Triumphant, Pictures, Irregularity, Movement, by Author, 2022.

7

8 [ VIII] [ I ] [ VI] [IX] Figure 1:

London Triumphant, List of drawings by Author, 2022.

9 [ II ] [ III ] [ I V] [ I V] [ I V] [ VII] [ V]

10 Figure 2:

London Triumphant, Chapter locations by Author, 2022.

[I] [II]

11 N S C A L E 1: 15000 [III]

IN T R O D U C T I O N

[THE] P I C T U R E S Q U E P I C T U R E S I R R E G U L A R I T Y M O V E M E N T

T O W N S C A P E

[THE] A R T I S T: S Y D N E Y R. J O N E S

A R T I S T: S Y D N E Y R. J O N E S

Sydney Robert Flemming Jones (SRJ) was born in Warwickshire, Birmingham in1881 and studied at the Birmingham School of Art from 1897-98, 189899 and 1901-02.1 The positioning of his education within history was long after the inception of the picturesque in the 18th century and just before the ‘Townscape’ movement had fully emerged in the 1940s. His contribution to the movement was exhibitions in different places documenting what he saw through the medium of drawing.

Having had the experience of working in an architecture practice, he was also a draughtsman, an etcher, painter and author. His work has been showcased at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, Royal Academy, Walker Art Gallery and others. He illustrated for The Times, Illustrated London News, London Transport and Studio Magazine. He has comprehensive experience in capturing Englishness within The Picturesque.

S.R.J is able to capture the essence of a place through a high level of detail and his ability to draw technically in accordance with the rules of perspective and orthographic drawings. Both of these factors create a more realistic impression. The drawings done in pencil appear loose and ephemeral, which creates an unforgettable nostalgic effect. All of these factors contribute to what makes his drawings so attractive.

He published his own books, which contained his drawings as illustrations and his personal commentary on what he observed, focused on what he was trying to communicate. These works include England in France, The Manor Houses of England, Thames Triumphant, London Triumphant and many others.

Cottage pattern books were a trend from the 18th century, continuing until the 20th century with varying popularity.2 They were a means for architects without funding/benefactors to trade the skills that they had to middle-class clients, illustrating cottage designs. After reading London Triumphant (LT), it is clear that there was an agenda embedded within the narrative of the book. Unlike other pattern books that had the primary role of illustrating architecture, styles and the architect’s skill as an artist. London Triumphant appears to have the purpose of presenting London in a picturesque way, whilst Hitler and the opposition within the war are often referred to in a condemning way, S.R.J’s presentation of London is picturesque and therefore worthy of preservation, making it a valuable instance where the picturesque can be seen as being used in a more sophisticated way in conjunction with a narrative.

14 [THE]

I N T R O D U C T I O N

Out of all the books in his oeuvre, London Triumphant (LT) stands out. The drawings within are detailed, atmospheric and compelling. LT can be seen as a picturesque account of the city, its images are captivating and convey the city in a pleasant way. At the time of its publication in 1942, World War 2 had been ongoing for 8 years and would not cease for another 3 years. Sydney R. Jones describes the war-torn capital of the country within LT. The years are filled with blackout nights that have rendered the city in darkness and the atmosphere is equally low. It is no longer possible to experience the city as it once was as many locations have been permanently destroyed. S.R.J presents London as a picturesque location that exemplifies nobility and Englishness with the intention of instilling inspiration throughout the nation during the war.3

This dissertation will analyse the drawings within Sydney R. Jones’ book to ascertain if they are picturesque according to a set of criteria defined by picturesque theory and whether he uses The Picturesque as a tool to support the nation throughout wartime. I will be interrogating Picturesque theory concerning Pictures, Irregularity & Movement specifically.

[THE] P I C T U R E S Q U E

The term Picturesque was once considered to be a radical mixture of art and life, it began at the start of the 18th century when the language was taken from the activity of painting. Protagonists of the picturesque were Sir Uvedale Price (1747-1829), Richard Payne Knight (1751-1824) and Humphrey Repton (1752-1818), who all made considerable contributions to picturesque theory and within the 19th century, there then was an important development of the picturesque within Germany, Camillo Sitte published his book City Planning

According to Artistic Principles and Heinrich Wölfflin (1864-1945) developed the theory behind the term malerisch.4 Within the 1940s the Townscape movement served as a new vessel for old picturesque ideas however, today there is a popular picturesque that is described in the Cambridge dictionary as“(especially of a place) attractive in appearance, especially in an old-fashioned way”5 and there is a more accurate, complex definition of the picturesque that I will define to provide a framework of how we will understand ‘The picturesque’ within this dissertation. The Picturesque can be defined as having the qualities of roughness, sudden variation and irregularity.6

15

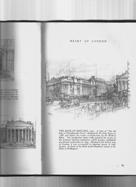

P I C T U R E S

Pictures are such a fundamental part of the ‘picturesque’ that the suffix ‘Esque’ at the end of picturesque suggests that the picturesque exudes the essence of pictures; opposed to pictures being a subordinate element related to the picturesque, but what are pictures?

The origins of the word ‘Picture(s)’ describes the physicality of the picture as an object which has value in itself as an artefact that is portable, but with this ability to move, also has the task of placing the viewer within the space of the scene, meaning the image (picture) displayed has the necessity of conveying the scene represented spatially and realistically.7

This understanding suggests that pictures, in essence, can be seen as a repository of the experience of different places. Generally, The picturesque defines 2 types of phenomenon. 1. When you see a place that embodies the qualities of the picturesque previously mentioned and 2. When you are looking at a picture and it portrays these picturesque qualities within it, thus making it picturesque. It is less common to refer to an object as being picturesque; rather it refers to a composition of things; whether in a picture or a place. Therefore, I will be reflecting on SRJ’s physical pictures and whether they are themselves picturesque and if the actual places do or may have been picturesque in their experience and time.

I R R E G U L A R I T Y

According to Camillo Sitte, The picturesque has to be based on the landscape and irregularities of the landscape. This natural topography is composed of peaks and troughs, brooks and streams and vast swathes of variety and irregularity that have formed due to differing conditions and factors. If these organic differences are respected and adhered to, then what emerges out of them will also display the characteristics of irregularity.

Camillo Sitte is considered to have been at the vanguard of the picturesque in urban planning and in his book City Planning According to Artistic Principles he describes the phenomenon of how fountains and monuments are placed within cities. He gives the apposite analogy, When snow falls, there are naturally

16

portions of snow that are untouched between the main naturally-occurring traffic routes. On these patches of snow, children build their snowmen as this is naturally where there is the most snow. Thus, in the same way, naturally emerging traffic routes have informed the placements of monuments, fountains and snowmen alike, equally the natural landscape when adhered to informs the picturesque.8

I will be using the principles he has established concerning the relationship between plazas, monuments and buildings. Rules such as; the centre of plazas should kept free and public squares should be enclosed entities, in order to analyse how these components present the Picturesque within S.R.J drawings and to test how these three principals influence or create picturesque conditions.9

MOVEMENT

The experience of the picturesque typically involves transitioning from one place to the next, this movement through space can be considered to be picturesque as it produces variety in visual experience.10

Yes, it is possible to experience a picturesque setting whilst static. However, this is not how we experience space or places that are picturesque. We have to arrive at them, move through them and leave them. It is this variety and position in space that is implied in relation to what has or will be travelled through which is what we experience in the picturesque. Thus, making movement an integral part of the experience of The picturesque.

Therefore, for the purpose of this dissertation, movement within SRJ drawings will be considered as pictures that suggest a place of transition. I will be using this principle to analyse whether Sydney R. Jones’ work is suggestive of movement within the picturesque representation of the city in London Triumphant.

17

T O W N S C A P E

Gordon Cullen is a British architect and urban designer; as a protagonist of the townscape movement, his most notable work was the book ‘Townscape: The Concise Townscape’ which was first published in 1961.

Almost 20 years after the publication of SRJ’s LT, which was published in the middle of World War 2. There is a distinct relationship between the two, where SRJ’s book overtly has the ambition of presenting London as a bastion for British ideals in opposition to Hitler.

Townscape was the new vessel for old picturesque ideas that were used with the intention of rebuilding post-war British cities. These ideas were solely focused on visual analysis and application concerning architecture and planning. Both S.R.J’s LT and the Townscape movement had the same agenda of preserving and restoring the nation’s cities, in this case, London. I will be using these ideas, specifically, Serial Vision, Concerning Place and Concerning Content as a means of analysing and understanding SRJ’s work in accordance with Townscape principles.

18

A B C

A

5: Lower Regent Street Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

26

Figure

0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N

A B C D

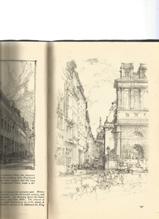

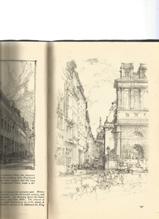

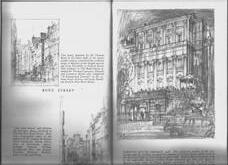

(Above) Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928. (Below) Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022.

(Above) Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928. (Below) Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022.

shading, being a mid-tone as it surrounds the two contrasts of light and dark. This attention to light and dark is called clair-obscur and the culmination of these three factors successfully serves to create a vivid picture of London at the start of LT by portraying it as a picturesque place.

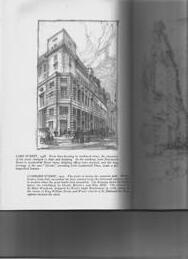

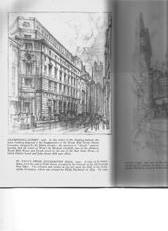

D R A W I N G II

Similarly, S.R.J’s rendition of Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C is an etching that is instantaneously eye-catching, as it has a quality of harmony within the drawing. The periphery of the etching on the right side is shrouded in darkness and unclear, due to its close proximity to the drawing vantage point, whilst the left side of the drawing is equally dark, the irregularity of the building plan in relation to the wall on the right side presents the details of the facade to the viewer. The building immediately behind this creates a sense of enclosure as it is just before the protagonist of the drawing, Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C. and blocks the view towards it. The subject of the study is a well-known church within The City of London which can be seen as a place that exudes the narrative of London that the author is trying to communicate of a place that is worth preserving. Still, according to the picturesque, the value of the painting lay not in the subject, but in the technique so how does S.R.J convey it through his drawing?

Throughout LT the illustrations are in the medium of etchings, pencil studies and pencil sketches and whilst the pencil is able to provide a more subtle variety of light/dark tones, S.R.J is able to convey this well in this etching. Within this drawing, there are a number of varying gradations of light and dark that create a sense of depth that is indicative of the architecture in this part of the city. The most striking feature of the drawing is the distinctive difference between light and dark, the picture is divided equally between these two tones based on where the light comes from and where the shadow falls within the drawing. This is a phenomenon that is characteristic of this built-up area of “The City” within London and through this, begins to communicate the overarching narrative that we spoke about, through the use of clair-obscur, unity through equal distribution of light and dark.

There are only two figures within the drawing that are used to demonstrate the enormity of the scale of the buildings in this scene. One figure appears to be slightly hunched looking at something obscured in darkness, while the other walks along the cobbled street. The drawing is an off-centred One-point

28

perspective that captures details of the detailed façade in the foreground, however, upon further inspection, it is clear that the drawing’s use of clair obscur is what is most captivating and communicates the picturesque. It appears as a united picture which was a necessary element of the picturesque. Therefore, this etching is successful in communicating the essence of the place represented.

Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

View Orientation

9: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C by Author (1924-1951), 2022.

30 Figure

0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N

31 Figure 10: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall Historical Map by Author (1924-1951), 2022. 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N View Orientation

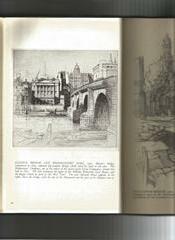

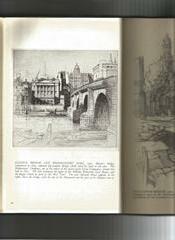

D R A W I N G III

In contrast to this, another etching by S.R.J is London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall which is less striking. Dark and light tones are not as evenly distributed and most of the surface of the picture is of the river Thames, a large water body that represents a space that receives direct light, with areas of shadow between the buildings and underneath arches. The dark tones are towards the centre of the picture’s surface and serve to add detail to the buildings that are affected by shadow, but it is still not as captivating at a glance as the etching of the church of St Michael when it does techically possess some of the same qualities of clairobscur. So why is this?

This mottled scene does not demonstrate clair-obscur as a whole, the drawing is less detailed than the former, elements that might benefit from being shaded are instead drawn with lines and despite the fact this is also a one-point perspective drawing, the image still appears to be flat and lacking depth. The built-up riverside, where Fishmongers hall sits below a lightly etched sky and above an entourage that you would expect on a river scene is lightly etched. Boats, bridge footings and small people are in the foreground. Despite the useful signifying things drawn of the place, the drawing lacks detail and appears as though the information is missing by comparison with the Church of St. Michael.

This is a good example of how a picture can contain instances of light and darkness within it, without them creating a unified whole. Despite its use in the appropriate places, there is a lack of that same level of detail across the entire drawing that leaves the drawing feeling unfinished. This may have been done by S.R.J in order to focus the reader on the buildings on the other side of the river, this combined with the one-point perspective view that is not very evident may have focused the gaze on the distant bank, however, the lack of detail is unsuccessful in unifying the drawing, communicating the activities of the people in place and is less successful at communicating The Picturesque than former drawings.

Within this drawing, there is a number of components of Gordon Cullen’s Townscape where he describes the experience of the progression through a built-up urban environment. Two key points of this are serial vision, where one’s progression through a space (Town/city) is made up of a number of stills along the journey that affect the viewer by the revelation of the streetscape. The

32

Figure 11: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

other element is the focal point which represents a signifying edifice that acts as a point in space to travel to.

The drawing appears candid, however, it also feels like it depicts a median between the two points of serial vision and focal point. Serial vision can be understood as the phenomenon of transitioning through space and it is represented by the series of images that are gradually revealed.21 The focal point is suggested by the skyline within the picture, it is usually indicated by a tall vertical element symbolizing a place of congregation.22 The fact that the detail of the drawing is in the distance is suggestive of both of these points.

Due to the fact the drawing is unfinished, the detail is further enough in the distance (smaller on the page) to require more information for a full image. Despite it having the ingredients to communicate the overarching narrative of the picturesque city, a place inspiring fondness, it leaves it lacking information that would otherwise communicate an accurate picture of the place.

Based upon the principles of the picturesque discussed relating to ‘pictures’ I conclude that LT makes a successful account of London in a picturesque way. S.R.J uses archetypal tools to convey charming moments such as the framed entrance onto Lower Regent Street. Potentially dank and intimidating spaces are conveyed in a charming way through the use of clair-obscur as explored when analysing his drawing of Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C and the fact that London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall was less successful than other drawings at the use of tools of the picturesque, is not necessarily a bad thing as it forms part of the visual variety required for the picturesque.

33

11

J. Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 22

12

William Gilpin, Three Essays: on Picturesque Beauty; on Picturesque Travel; and on Sketching Landscape, London, Printed for R. Blamire, 1792, p.42-46

13 Sydney R. Jones, London triumphant, London, Studio Publications, 1942, p.50-51

14 E. H. Gombrich, ‘The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape’, in Norm and Form, London, Phaidon, 1966, p.123-126

15 Marc Auge, non-places introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity, John Howe, London, Verso, 1995, p.77

16 Lexico Dictionary, coup d’œil definition, https://www.lexico.com/definition/coup_d’%C5%93il

17 J. Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 23

18 Ibid., p. 23

19 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 21

20 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, op. cit., p. 23

21 Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Arhitectural Press, 1961, p. 9

22 Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Arhitectural Press, 1961, p. 26

23 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities,

34

C H A P T E R I E N D - N O T E S

L I S T OF I L L U S T R A T I O N S

C H A P T E R I P I C TU R E S

Figure 1: London Triumphant, List of drawings by Author, 2022.

Figure 2: London Triumphant, Chapter locations by Author, 2022.

Figure 3: Chaper I Location Map by Author, 2022.

Figure 4: Old London Bridge by Sydney R. Jones, 1921.

Figure 5: Lower Regent Street Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928.

Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022.

Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

Figure 9: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C Historical Map (19241951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 10: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall, Historical Map (1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 11: London Bridge and Fishmonger’s Hall (1924-1951) by Sydney R. Jones, 2022.

35

36 Figure 12:

Chaper II Location Map by Author, 2022.

100m0 100m 200m 300m 400m 500m 1:5000 N IV V VIII

C H A P T E R

I R R E G U L A R I T Y

II D R A W I N G IV D R A W I N G V D R A W I N G VI

C H A P T E R II I R R E G U L A R I T Y

The main contradiction of the picturesque is that the process of achieving that which is picturesque is actually dependent not on pictures, that is to say how a place looks but on how buildings/ streets are laid out, which in turn influences how things come into view within the space.22

For clarity, it is important to define that S.R.J’s drawings, being 2d pictures that illustrate 3d space, rely on an understanding of what is happening within the plan of the space being illustrated in order to have an accurate representation that is picturesque. According to Nikolaus Pevsner, irregularity within the plan is what is needed for this as this is what actually dictates the representation of the picturesque scene. This suggests that the picturesque is an experiential phenomenon and not an observational one.23 So again, by representing London in this manner he reminds the viewers that it would not be possible for them to experience London as picturesque if it is not preserved.

Figure 13: narrow streets in The City of London by Author, 2021.

Since picturesque architecture is a phenomenal experience that is not purely about observation, John Macarthur states that its formal description is not possible as the experience requires a progression through space with a series of varying still pictures, where factors such as sequence and duration are relevant.24 However, around the 1940s, a process called townscape had begun which can be seen as the of old picturesque ideas that sought to implement the principles of the picturesque in order to plan the city’s landscape. Qualities that are similar to those promoted by Townscape can be found in the work of nineteenth-century Austrian architect, Camillo Sitte.

In Camillo Sitte’s book, City Planning according to Artistic Principles, each chapter is arranged into various principles that address the city in a different way. S.R.J’s drawings will be described and analysed in accordance with these principles in order to understand if these principles create irregularity within his work and whether his drawings can be considered to be picturesque.

38

It is variety within the picturesque that stimulates visual pleasure and creates aesthetic value, and this is inextricably connected to irregularity within the planning and layout of buildings, public squares, plazas, monuments and streets. Bold buildings are typically located around a plaza with monuments in the centre that could be celebrated. This principle is described as having unifying qualities that draw people to its centre. 25 As was mentioned earlier, the oldest areas containing monuments are usually the most irregular in form26 and views with monuments in them are most aesthetically pleasing when they are placed on the periphery of a plaza.27 Plazas and squares are designed to be experienced from their longest length in order to increase their dramatic effect and enclosing them preserves the character of the space. Additionally, irregular plans create views that are aesthetically pleasing as they appear organic, a subjective point of view from Camillo Sitte, nevertheless is suggested by Figure 13. Images of the winding streets of The City of London and the vistas created from the free-flowing streets. Plaza groupings within old towns frequently consisted of multiple places conjoined to form one, this phenomenon was widely done in order to create the ideal view of a prominent building within the plaza. Essentially, the chosen elevation dictated the layout of the plaza.28

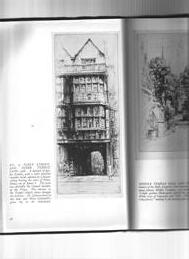

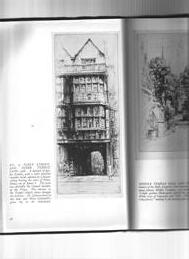

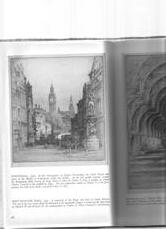

D R A W I N G IV

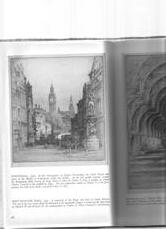

Gray’s Inn Hall, pictured on the next page, shows the “sharp perspective”29 of the buttressed windows and the view is indicated on the plan of the square. The Gestures of figures are roughly sketched in the foreground with the elevation of one of the periphery buildings in the background, where the perspective is guiding the viewer. An entrance to the square is suggested to the right of the drawing that is drawn in loose linework and legal buildings form a perimeter around the square with Gray’s Inn Hall, the most prominent building toward the South. According to Camillo Sitte, the forum, agora and public square served to frame public life,30 in the case of Gray’s Inn the square serves 1, as a transitional space and 2. as a place for lawyers occupying the periphery buildings to take lunch. The drawing captures the South pavement along with the elevation of Gray’s Inn and the street reflects the quiet nature of the ‘private’ square that is used primarily as a place to stroll through. However, a hallmark of the square that made it picturesque was its ability to frame and facilitate public activity. In the picturesque, some artists use a tool called appropriation to inhabit the scene, conforming to the picturesque standard of having a space

39

(Above) Figure 14: Gray’s Inn Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933. (Bottom left) Figure 15: Gray’s Inn Square and Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933. (Bottom right) Figure 16: South Square Gray’s Inn by Sydney R. Jones ,1933.

41 A B C D 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N Figure 17: Gray’s Inn Hall, Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022. Figure 18 Figure 19 Figure 14

42

(Top - Bottom) Figure 18: Sequential Images depiting approach to Gray’s Inn Hall, from Northern entrance by Author, 2021.

C D

Figure 19: Diagrams illustrating approach to Gray’s Inn Square from West by Author, 2022.

filled with life and activity,31 however, S.R.J chooses to articulate the true nature of the space accurately as a quiet space opposed to contriving what was not there.

Four archways frame entrances into the square along each perimeter, as indicated on the plan and photos, they intersect the periphery elevations creating tunnels into the square. This way there is no clear sightline outside of the square or any other entrance, allowing for a continuous elevation and unbroken sense of the character of the square. This artifice was taken from old city planning and was seen to create picturesque settings by allowing each square to retain its own character. The drawing of Gray’s Inn Hall is successful in suggesting the experience of the square’s turbine plan layout, where only one entrance is visible from a viewpoint. Although no entrances are directly visible in the picture, the layout and material context is implied. Within the picture, no monuments are visible, despite the monument of Francis Bacon Figure 16 being visible on the plan. Consequently, the view although dynamic due to the buttressed elevation of Gray’s Inn, lacks the excitement that Camillo Sitte describes when monuments are placed along the periphery of a square.

Camillo Sitte states that there are two types of a city square, deep vs wide, which are defined by the person’s position within the square and the direction of their sight in relation to the major building within the square.32 What is interesting about Gray’s inn Hall, the square is experienced from its four sides and from each entrance. The most dramatic of these is the entrance entering from the North that looks towards Gray’s Inn Hall, as the elevation of the hall offers the most dynamic façade of all the elevations and the entrance looks directly at the elevation. The second is from the entrance from the West that looks across the elevation of Gray’s Inn. As Visible in Figure 14, the buttresses that are captured in the sketch perspective are dynamic and add presence to the scene. Finally, the arrangement of the plan layout of the square itself is quite regular being a rectangle, however, the approach to the square from the neighbouring entrances can be seen to be irregular as the states of enclosure vary from narrow settings to open and the approach to the square is not necessarily linear either.

The approach from the East guides you towards the large external façade that has one small irregularity at its base which is the entrance to the square and although it is a linear approach, what the viewer encounters visually is a variety of views, each different from the last Figure 19. This effect when experienced

44

suggests the space beyond at the entrance and reveals the square beyond. The approach from the East has the same variety of exposure vs enclosure as the approach takes you from an open environment to an enclosed one through the narrow buildings, finally revealing the uniform square. Therefore, despite the fact, that the square itself is a regular shape the experience of the approach to it is quite irregular. This is not displayed within S.R.J’s drawings, however, he has chosen to illustrate moments within the square that do not show how regular it is. 33

D R A W I N G V

New Court from Fountain Court, Middle Temple shows the view North that is framed by two trees, one in the foreground and the other toward the middle of the composition. There is less detail toward the edges of the picture, gradually increasing past the boundary trees until the focus of the image (central to both trees), where windows and brick texture are accurately drawn in a light pencil that focuses your attention. Tree shrubbery towards the top of the drawing, although rough, is fitting as it provides a stark contrast to the detailed building façade in the background, steps leading to the neighbouring court, and the fountain and pavement in the foreground. Three figures are lightly drawn within the composition, not easily detectable but give a good sense of scale and occupation of the space presented. The court is an irregular shape as the boundaries that define the court are not the typical boundary you might expect. The Western boundary is articulated as the elevation of a building, however, the North and South boundaries are occupied by stairs and parapet that guards against a steep level change. The Eastern boundary is extended and continues until Middle Temple Lane. Essentially, the space is an amalgamation of two courts and S.R.J’s drawing illustrates a view of one from the other.

As spoken about earlier in this chapter, grouped plazas or public squares are often used as a tool to exemplify a particular building or feature contained within the space that is worthy of display. By giving the aforementioned entity distance, it can be viewed from the optimum vantage point as the surrounding context respects the feature. There is no such building or feature within New Court and Fountain Court, however, the space is enhanced because of its level changes. Whilst progressing through the space, each level

45

View Orientation

46 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N Figure 20: Gray’s Inn Hall, Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 21: New Court from Fountain Court, Middle Temple, 1930.

change creates a dramatically different impression from the former level within the plaza and even forms part of the feature of interest in S.R.J’s study of the courts. Figure 21 Is this obvious from S.R.J’s 2D drawing? It is suggested by the distance that he is able to capture within the image. Also, the fact that what is in detail is in the distance suggests that there is more to be discovered whilst moving throughout the space.34 The distance between the vantage point and the focus of the drawing pulls you into the scene. As the space is made up of two distinct shapes, each one has a different experience. Fountain Court has a long procession towards the fountain from Middle Temple Lane and it occupies the middle level in relation to the neighbouring New Court and lower level. This creates a picturesque moment as there is a break in the language of the plan. A moment of irregularity within the typical elevation. The shape of New Court

has less opportunity for dramatic effect as all four sides are a similar length and relatively small compared to Fountain court. However, its positioning after a sequence of narrow partially covered overheard and the busy roadside along Fleet Street provides a strong contrast as it is the end of this highly varied journey from North of the site, the opposite direction of the drawing. S.R.J captures the character of this space very well. It is a combination of the foliage within the scene, the level change, and the opposing qualities of spaces, (New Court being narrow and shaded, Fountain Court being open and light). It is not clear if S.R.J made a distinct attempt to document the area in detail with the intention of expressing the nature of the plan of the space and its irregularities, however, all of these factors are part of what makes this drawing so successful for communicating the picturesque and displaying irregularity in perspective.

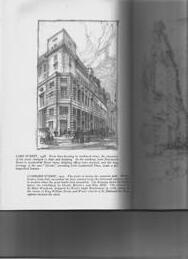

D R A W I N G VI:

Lombard Street is a view taken at the junction of King William Street and Lombard street that captures the vista facing East-South-East. The drawing shows the elevation of buildings on the left, receding into the distance, building details are partially drawn to give a sense of the architectural character. The elevation of St. Mary Woolnoth is to the right of this facing the surface of the page and provides a sense of symmetry as a façade drawn in detail. S.R.J’s position when taking reference for the drawing is elevated from street level, as the view gazes over people on the street in the foreground. Vehicles, people and street furniture provide context as you look into Lombard Street, where the perspective leads your vision with a church spire in the background. Lombard Street is one of seven main arteries that lead to Cornhill, present-day Bank. As mentioned earlier in the introduction, picturesque locations can often be attributed to the plan’s natural formation based on the existing topography. Within the city of London, there are many examples of this, there is a distinct character of the street here being narrow, skewed and winding both in plan and elevation that creates a unique visual experience. Figure 23.

The shape of the street is a concave form, splaying downward toward the South before curving up again when looking at the plan view (Right). Lombard street is a good example of the effect of the winding street as the building facades on the left of the page do not follow the linear perspective line due to their undulation and the street can be visibly seen to recede behind the

48

church of St.Mary Woolnoth. Thus the irregularity in the plan is visible in the perspective view and adds to the variety in the drawing. As well as the concave nature of Lombard street, the junction in the foreground also widens which provides functionality to the space for traffic and gathering. Today the space is predominantly pedestrianized with underground access. This allows a sightline up toward Lombard street and having visited the site myself, it appears to be an attractive vantage point in otherwise narrow streets. As represented in S.R.J’s drawing, St.Mary Woolnoth presents its detailed façade to the space in front, optimising its location and creating a place at this junction. This is not immediately evident when looking at the drawing, but the irregularity in the plan has created variety in the perspective scene such as the experience of elevations facing different directions, figures occupying the space in the foreground and the juxtaposed scene that derives directly from the planning of the street. In conclusion, Lombard Street is a successful personification of a space that possesses activity that reflects irregularity. Every element within the drawing suggests that there is a lack of uniformity. The people crossing the street, varying levels of shade and detail on building facades and the flecked effect of the pencil on the surface of the picture.

The drawings discussed within this chapter mostly display irregularity in the way they are drawn, fading towards the edges of the composition, with Gray’s Inn Hall as the exception, all drawings contain irregularity within them in this way. We can see that S.R.J does apply the qualities of irregularity by selecting locations where the planning techniques used to direct the user’s view promote places that are not uniform. In most cases, to the boldest building within the place (main characteristic building of the area), or conceal the user’s view and prolong the revelation of the view chosen. He adopts a similar technique with the order of his drawings, presenting a variety of pictures. Despite the fact that he often represents linear and regular forms, there is a free-hand quality to his drawings that also creates the instances of irregularity in his works.

49

View Orientation

50

Figure 22: Lombard Street by Sydney R. Jones 1922.

51 Orientation 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N Figure 23: Lombard Street Historical Map by Author, (1924-1951), 2022.

24

Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 110.

Anon , ‘ A Programm e for th e Cit y o f London’ , The Architectural Review 97 , no . 582 , Jun e (1945) ; Nikolau s Pevsner , ‘Visual Plannin g and the City of London’, The Architectural Association Journal LXI , no . 69 9 (1945); Nikolau s Pevsner , ‘Visua l Planning and the Cit y o f London’ , The Architects’ Journal 102 , no . 265 5 (1945).

25

26

Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Architectural Press, 1961, p. 17-19.

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p.146, 151-152.

27

28

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p. 160

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p. 162.

29

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p. 192193.

30 Sydney R. Jones, London triumphant, London, Studio Publications, 1942, p. 72.

31

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p. 151, 154.

32 Humphry Repton, The Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the Late Humphry Repton Esq., ed. John Claudius Loudon (London: 1840), p.601.

33

34

35

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p. 177.

Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Architectural Press, 1961, p. 25, 33, 69.

Camillo Sitte, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and

52

C H A P T E R II E N D - N O T E S

L I S T OF I L L U S T R A T I O N S

C H A P T E R II I R R E G U L A R I T Y

Figure 12: Chaper II Location Map by Author, 2022.

Figure 13: narrow streets in The City of London by Author, 2021.

Figure 14: Gray’s Inn Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933.

Figure 15: Gray’s Inn Square and Hall by Sydney R. Jones, 1933.

Figure 16: South Square Gray’s Inn by Sydney R. Jones ,1933.

Figure 17: Gray’s Inn Hall, Historic Map(1924-1951).

Figure 18: Images depiting approach to Gray’s Inn Hall, from Northern entrance by Author, 2021.

Figure 19: Diagrams illustrating approach to Gray’s Inn Square from West by Author, 2022.

Figure 20: Gray’s Inn Hall, Historic Map(1924-1951) by Author, 2022.

Figure 21: New Court from Fountain Court, Middle Temple, 1930.

Figure 22: Lombard Street by Sydney R. Jones, 1922.

Figure 23: Lombard Street Historical Map by Author, (1924-1951), 2022.

53

100m0 100m 200m 300m 400m 500m 1:5000 Figure 24: Chaper III Location Map by Author, 2022 N VI III II VII

M O V E M E N T

C H A P T E R

III D R A W I N G VII D R A W I N G VIII D R A W I N G IX

C H A P T E R III M O V E M E N T

The context in which the picturesque city is designed and experienced is one where the user moves throughout the space and it is this gradual movement from place to place that is intrinsically linked to the experience of a picturesque place.

The action of moving through space in a varied context, where not only everything within the user’s view has significance, but also that which has already receded out of view, or is yet to arrive in view is important. As we discussed in the last chapter, the connection to planning and layout, from one space to the next within the picturesque, means there is a link to ‘movement’, as this is the only way we can partake in this experience. However, here lies the contradiction and main source of confusion, how is it possible to convey movement in a static 2d picture? I will begin by aiming to articulate what this means and how this can be conveyed and understood in relation to S.R.J’s work.

Architects use space in the same way that a sculptor uses clay,35 movement is a privilege of space, and there are different possibilities with different amounts of space. For example, a grand plaza, a hall, or a small room, all have different possibilities, some of which are better suited to particular activities than their counterparts, the function of a piazza would not suit the needs of a bedroom as well as a small intimately lit room would, therefore it is not necessarily true that the larger or grander the space the better. The possibilities are what have value, they are what S.R.J’S drawings evoke by ways of imagination. In a way, the quality of a space (scale, atmosphere, etc). can be represented and understood by the architecture, which in turn represents factors such as value. Within LT it is clear that architecture’s true value lies in its ability to frame human life and facilitate a variety of activities where you could imagine yourself.

“Architecture imitates us in our capacity for movement, but not our actual passage through space, rather, the gestures through which we give movement a communicative and affective form.”36

Heinrich Wölfflin was a Swiss art historian and educator who developed concepts surrounding movement and form in relation to Baroque architecture.

56

His work suggests that ‘semblance’, which is when an entity resembles the qualities of another entity, in a way is a movement to that which is being represented, a nod to it if you like, what Walter Benjamin calls aura, the nonsensuous representation of something37

It is this process of identification that must take place in the 2d drawing of a 3d place. Where movement, as a fundamental part of the picturesque human experience and a dynamic/animated action must be expressed in a static image.

“Wölfflin describes his anthropopathic theory in the following way: (1) Every emotion has an expression, the physical manifestation of the mental act; (2) when we imitate the expression of the emotion, we also experience this emotion; (3) we then unconsciously transfer our emotional response to the person or object.”38

In the same way that a person might physically attempt to illustrate the actions of the thing they are trying to describe e.g. miming driving, when they do not have the ability to speak or hear, through the process of gesturing a turning, that process of representation is called signification and is the task drawings have when signifying the action of movement.62

Buildings are designed for the proportions of the human body meaning a static entity, but they also have to enable the activities for which they were designed, therefore it also has to facilitate the action of movement, a building’s shape is a consequence of what it is designed for, thus it is an expression of that. For example, a glove could be seen as an expression of a hand, or a shoe could be an expression of a foot and in that same way, a building, despite not being a literal concave mould of the human figure, or as robust as a glove or a shoe, still has the means to facilitate movement depending on the quality of the space. Thus a building is an expression of movement. I am looking at S.R.J’s work in order to understand how the buildings / streetscape within are shown to facilitate movement within the drawing.63 At the time of the publication of LT, this fundamental part of being human that we experience was being challenged by the war. As is the case within previous chapters that we have discussed, S.R.J aims to present London as a place worth preserving by highlighting the qualities of London that are cherished and could potentially be lost.

57

D RA W I N G VII

Lloyds Leadenhall street was a preliminary sketch for etching of the then-new building of corporate underwriters.64 The preliminary sketch shows the elevation of the building; vehicles appear in the foreground at the bottom of the page on either side of the frame. Immediately behind this are gestures of people that are clustered together at the entrance of Lloyds. Finally, the background and majority of the sketch’s composition comprise the Lloyds building elevation. Throughout the drawing, the linework is loose but suggestive and the gestures of human figures appear to be moving upward into the building. At the same time, the elevation has depth where the building elevation steps back. The drawing has a rough sketch effect, where the form of details is achieved along the edges of the drawing through gestural hatches. Detailed areas of the drawing are drawn in a thicker pencil.

The road at the bottom of the page is subtly suggested by markings that ground the vehicles on them, but together they imply movement as they appear reflective of the cars on top of them. Firstly, as an archetype, the road and the car are clear signifiers of transportation, but the way they are drawn is lightly blurred, maybe due to the fact this was a preliminary sketch but actually has a quality of motion to it. The placement of them on the page suggests they are appearing in motion along the road, across the front of the picture as the car on the right is partially out of the frame of view, while the left side of the page also displays a larger vehicle that is just coming into the frame of view. This is the most notable sign of movement in the drawing in contrast to the static elevation of the Lloyds building and effectively illustrates a dynamic scene. People in the centre of the drawing are very abstractly drawn, which is fitting to the level of detail in the drawing and although they do not have the same quality of motion as the vehicles, their abstract nature implies movement as well as the distance from the drawings vantage point. However, the positioning of them within the drawing makes it clear that there is a progression into the building on the other side of the road from where the drawing was taken. This is an excellent example illustrating how movement can be implied and understood in a 2d picture.

58

Figure 26: Lloyds Leadenhall street by Sydney R. Jones, 1928.

25: Lloyds Leadenhall street Historical Map by Author, (1924-1951), 2022.

59 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N View Orientation

Figure

D R A W I N G VIII

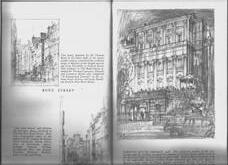

Bush House, Strand is a pencil drawing that was created in 1930-31 and captures the church of St. Mary and the American edifice, Bush House.65 The drawing’s vantage point is from the pavement as indicated in the plan and looks towards Bush House toward the left of the composition. The curved pavement and road occupy the centre of the composition with St. Clements Danes Church in the background as the focal point and the church of St. Mary on the right of the page. People and cars that reflect the time fill the centre of the composition and clouds are lightly suggested above between the two buildings on either side. There is a notable difference between light and dark within this drawing that is articulated through heavy lines, visible on the elevation of the church of St. Mary and the colonnades of Bush House, against light lines, as opposed to shading like S.R.J’s rendition of the Church of St. Michael in chapter one. The scale of the colonnades in relation to the simple gestures of people directly in front ignites the imagination of how people might have transitioned from the street across or into the building.

Again, the road is loosely drawn but these gestures are concentrated underneath vehicles, with dark values equal to the weight of what is reflected, the shading could indicate either shadow or reflection in the water and although the floor appears to have a sheen to it that resembles water, it appears to be representing floor shadows. The pavement floor below people walking is sketched in a lighter value but also only located under the entourage in the scene which implies that they are tracks left from the movement of the people and cars, this creates a juxtaposed scene. The pavement is filled with people, there are more discernible figures in the foreground, some appearing to be in a stride of movement, faintly sketched for an ephemeral appearance. Further in the distance the figures become denser and are more suggestive as they have less detail but serve in creating an impression of movement. However, it is not only the archetypal elements of travel that contribute to the signification of movement within the drawing. The tower of St Clement Danes Church in the distance resides as what Gordon Cullen coined the ‘focal point’, a point within the city that can be seen from afar and directs people towards it for congregational gatherings and within this drawing, given the orientation of traffic, it appears to be the destination for the figures that express movement.66 The placement of the church of St Mary creates an instance of punctuation, terminating the view

60

directly to St Clement Danes Church which creates a point of interest in the foreground of the drawing where activity and movement is concentrated.67

Through the use of archetypal figures and their relationship to buildings in the distance, specifically St Clement Danes Church, S.R.J is able to illustrate movement by suggesting an extrinsic relationship between the people in the foreground and buildings in the distance. As seen in many of S.R.J’s drawings, flecked line work with an ephemeral pencil technique also creates the impression of motion.

Figure 27: Bush House, Strand by Sydney R. Jone, 1931.

61

View Orientation

62

Figure 28: Bush House, Strand Historical Map by Author(1924-1951), 2022.

63 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N

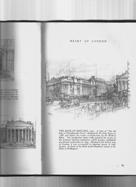

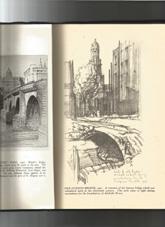

D R A W I N G IX

The Institution of Civil Engineers, Great George Street is a two-point perspective drawing with Big Ben in the background as the focal point.68 From this vantage point on George street, two elevations are visible, the entrance on the left that is facing the North and the West elevation which is partially shaded due to its close proximity to the neighbouring building. Three wide pavements form a T-junction at the point of the North-Western elevation intersection point with a road that runs across the entrance of the Institute of Civil Engineers.

Background buildings are slightly obscured in darker light values and cars and people are suggested as entourage within the streetscape. Unlike other drawings that have been analysed within this dissertation, this drawing is framed by the neighbouring buildings, whereas other drawings by S.R.J often fade in detail as you approach the sides of the picture. The building on the left is in the greatest detail, showing façade details and articulating them with shading that reflects the direction of the geometry. For example, vertical lines are shaded vertically and the right is framed by a building in the distance and is merely suggested as the corner stands in deep shade.

The view for this drawing is extremely powerful owing to the two-point perspective view chosen. The subject of the drawing is the Institution which does not appear to interact with the street in any way, apart from the framed entrance on the Northern elevation, however, the street / road is the most captivating element within the drawing. All of the instances of archetypal figures that represent movement only become clear with a close inspection as they are concealed in shade. It is the use of perspective that creates such a compelling suggestion of movement within the drawing. The lower left of the drawing illustrates pavement shading, sketched horizontally to ground the figures in the distance on the pavement that leads to a vanishing point.

Immediately beside this, the road has a series of lines that stem from the same vanishing point. What is interesting about these is that there should not be shading within the road where indicated as the light is coming from the opposite direction and there is unobstructed space between the source light and where this shading is shown according to the shading on the right of the page. This is the most accurate indication of the light source as the building opposite clearly shades the Western elevation of the institution. Thus, if the lines shown here are not illustrative of shade and the representation of what is there, they are contrived in order to communicate the narrative of the drawing.

64

With Big Ben in the background and figures and cars placed in the orientation of the road, the lines that follow the vanishing point clearly indicate movement along the street that sits so close to the institute but is distinctly separate. The figures within the drawing appear to move towards the Houses of Parliment. This communicates the unique nature of traffic within the busy built-up urban metropolis that is London. If we proceed with the understanding that the shading on the right of the page is accurate, then it can be understood that S.R.J is choosing to utilise the second vanishing point to represent that shading of the neighbouring building on the street in a way that expresses movement on the street in the most dramatic way possible.

The quality of movement in 2d drawings is typically expected to be expressed as figures or vehicles in motion, however, not all of S.R.J’s drawings have these signifiers and are still able to suggest a sense of movement. It is clear that this is achieved by a variety of means. Archetypal figures, the use of perspective whereby all lines, whether they are articulating a 3d object, water, shadows, etc relate to the respective vanishing point which suggests a transient state, articulating features in the distance and the foreground in detail to create a sense of here and there and finally a variety of drawing styles and medium. This final characteristic when looking at the book as a whole serves to create a juxtaposed sequence that is reflective of what one is able to observe in the picturesque city.

65

View Orientation 0 20m100m 20m 40m 60m 80m 1:1000 N Figure 29: The Institution of Civil Engineers, Great George Street, Westminster by Sydney R. Jones, 1936.

66

Figure 30: The Institution of Civil Engineers, Great George Street, Westminster by Sydney R. Jones, 1936.

C H A P T E R III E N D - N O T E S

Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986, p. 197.

36 Geoffrey Scott, Architecture of Humanism, Nabu Press, 2010, 227.

37

38

John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 234.

Walter Benjamin, ‘On the Mimetic Faculty’, in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978, 333.

39

Mallgrave and Ikonomou , Empathy, form, and space : problems in German aesthetics, 1873-1893 Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, Chicago, Illinois, 1994.

40 Lionel Bailly, Lacan A Beginners Guide, London, Oneworld Publications, 2009, p. 42-45.

41 John Macarthur, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007, p. 251.

42 Sydney R. Jones, London triumphant, London, Studio Publications, 1942, p.137.

43 Sydney R. Jones , London triumphant, London, Studio Publications, 1942, p.199.

44

Gordon Cullen, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Architectural Press, 1961, p. 26

68

L I S T OF I L L U S T R A T I O N S

C H A P T E R III M O V E M E N T

Figure 24: Chaper III Location Map by Author, 2022

Figure 25: Lloyds Leadenhall street Historical Map by Author, (1924-1951), 2022.

Figure 26: Lloyds Leadenhall street by Sydney R. Jones, 1928.

Figure 30: London Triumphant, Pictures, Irregularity, Movement, by Author, 2022.

Figure 27: Bush House, Strand by Sydney R. Jone, 1931.

Figure 28: Bush House, Strand Historical Map by Author(1924-1951), 2022.

Figure 29: The Institution of Civil Engineers, Great George Street, Westminster by Sydney R. Jones, 1936.

Figure 30: London Triumphant, Pictures, Irregularity, Movement, by Author, 2022.

69

70

Figure 31: London Triumphant, Pictures, Irregularity, Movement, by Author, 2022.

71 N

72

O

N C L U S I O N

C

This dissertation sets out to ascertain if the drawings within Sydney R. Jones’ book are picturesque according to a selected set of rules defined by picturesque theory and how he uses The Picturesque to encourage the nation to feel inspired in their capital. The selected principles as defined by the chapter headings are, firstly, Pictures, that the drawings present a picture of the overarching narrative, (the success of London) through the use of a balance between light and dark and whether this creates a unity of the entire object. Secondly, Irregularity, the drawings illustrate the irregularity that is present in the real context and how these irregularities are manifest within the drawings. Thirdly Movement, that the drawings convey movement or the opportunity for movement in the place being conveyed.

Right away it is clear that S.R.J has the task of conveying place in a believable way in order to capture that which is picturesque within the city. This requires not only recording the likeness of the place but also the actual essence of it. S.R.J conveys his narrative through pictures through the use of clair-obscur, to create a balance of light and dark within the drawing. This technique is widely used throughout all of his drawings, giving each illustration a sense of contrast, however, it is not always successful in creating an exact likeness as it is a tool that is required to be used consistently within the drawing and not partially. Instances where S.R.J creates faster or less detailed drawings are sometimes seen to lack the verisimilitude that is evident in drawings that have clair-obscur throughout.

Coup d’œil is another component that is instrumental within picturesque theory and key to creating drawings that reflect The Picturesque. S.R.J creates drawings that have an even distribution of detail of light and dark that is immediately attractive at a glance. Throughout LT there is a clear variety in the level of detail, time and attention paid to each drawing, however, they mostly convey coup d’œil, whether they appear to be an etching, a detailed pencil drawing or a fast pencil sketch. All of these tools used by S.R.J contribute to creating a united object (l’unite d’objet), meaning a picture that appears whole and is not lacking anything. Paradoxically, the book as a whole has the quality of a united object because there are instances where this is lacking.

With regard to irregularity, S.R.J’s choice of drawing locations is reflective of places that are picturesque due to their irregularity in the plan. Meaning that the plan is not even or linear but instead inconsistent. There is a clear pattern

74

C

O N C L U S I O N

where archetypal techniques that are representative of picturesque spaces, specifically looked at within this dissertation, the concave plan that creates winding paths or punctures in an elevation creating disjointed angles that frame the scene, are drawn in a way that emphasizes the most irregular parts of the plan, which in turn creates irregularity within his drawings. In this respect, the way that he portrays the city can be related more to Townscape with its rules that suggest that the picturesque is achieved through the variety encountered when progressing through the city. There is also irregularity in the level of finish across the drawings within LT that makes the book very engaging, having a variety of visual stimuli.

When it comes to movement being the third focus of this dissertation, S.R.J uses archetypal figures that signify movement such as people and vehicles that appear in motion. He expresses movement through a variety of media such as; signifiers of buildings that are not merely static but express their functionality which is to facilitate the experiential activity that takes place within or around them. Movement is also expressed through the use of perspective in relation to the vantage point that the drawing was taken from. By drawing key horizontal lines that recede in perspective to a vanishing point, S.R.J is able to suggest movement or motion, in some instances giving the impression that there is actual activity within the picture. As figures are sometimes drawn in an obscured way, it is not easy to locate them, this in addition to striations that follow perspective is indicative of a scene that has movement. Finally, he uses tools that were presented within the townscape movement, whereby buildings in the foreground and distance are drawn with equal detail in order to suggest places of departure and destination within a drawing. This successfully creates a picturesque place where there is a variety of possibilities that are suggested through the use of these tools.

Concluding, S.R.J is successful in presenting London as a picturesque city according to pictures, irregularity and movement, the three principles of the picturesque analysed within this dissertation. Presenting a variety of places in a unified way individually but also collectively, he is able to convey different places of London aestheticizing the city’s irregularities, creating the impression that the reader is moving throughout these dynamic scenes whilst progressing through the book.

75

B I B L I O G R A P H Y

Ackroyd, Peter, (2000) London: The Biography, London : Chatto & Windus

Anon , ‘ A Programm e for th e Cit y o f London’ , The Architectural Review 97, no. 582, June (1945); Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Visual Planning and the City of London’, The Architectural Association Journal LXI, no. 699 (1945); Nikolaus Pevsner, ‘Visua l Planning and the Cit y o f London’, The Architects’ Journal 102 , no. 265 5 (1945).

Bailly, L. Lacan A Beginners Guide, London, Oneworld Publications, 2009

Benjamin, W, ‘On the Mimetic Faculty’, in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1978.

Cullen, G, Concise Townscape, Oxford, Architectural Press, 1961. E. H. Gombrich, ‘The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape’, in Norm and Form, London, Phaidon, 1966

Jones. Sydney R, London triumphant, London, Studio Publications, 1942.

Macarthur, J, The Picturesque. Architecture, disgust and other irregularities, Abingdon, Routledge, 2007.

Mallgrave and Ikonomou , Empathy, form, and space : problems in German aesthetics, 1873-1893 Getty Center for the History of Art and the Humanities, Chicago, Illinois, 1994.

Marc Auge, non-places introduction to an anthropology of supermodernity, John Howe, London, Verso,

Price, U, An Essay on the Picturesque as compared with The Sublime and The Beautiful and on the use of studying Pictures for the purpose of improving real landscape, J.Robson, London, 1794.

Repton, H, The Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the Late Humphry Repton Esq., ed. John Claudius Loudon (London: 1840)

76

Gilpin, W, Three Essays: on Picturesque Beauty; on Picturesque Travel; and on Sketching Landscape, London, Printed for R. Blamire, 1792.

Scott, G, Architecture of Humanism, Nabu Press, 2010.

Sitte, C, City Planning According to Artistic Principles, George R. Collins and Christiane Crasemann Collins, New York, Dover Publications, INC, 1986

77

78

Figure 4: Old London Bridge by Sydney R. Jones, 1921.

Figure 4: Old London Bridge by Sydney R. Jones, 1921.

(Above) Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928. (Below) Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022.

(Above) Figure 6: Lower Regent Street from Picadilly Circus by Sydney R. Jones, 1928. (Below) Figure 7: Lower Regent Street Sequential Journey indicated on plan, by Author 2022.

Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.

Figure 8: Church of St. Michael Paternoster Royal & Innholders Hall E.C, by Sydney R. Jones, 1927.