It is with my own sense of profound optimism that I introduce our fourteenth issue of 3198.

With each issue of 3198, I am consistently struck by our theme’s nuance, viewed against the backdrop of the broader cultural and geopolitical landscape. The notion of optimism can often feel naïve or disingenuous when presented independent from and unencumbered by challenging and complex realities. In fact, optimism requires a sense of hope and belief in our future precisely when staring down these challenges.

You may recall from some of my other contributions to 3198 that I often struggle with the notion of scale when contemplating meaningful change. Whether casting one lonely ballot into a sea of electoral mayhem, diverting a single plastic bottle from an ever-expanding landfill, or mitigating one thermal bridge at the head of a window assembly, it can be easy to lose the thread of impact at a larger scale. Even within our studio, there may be moments when we all may feel detached from a larger mission, whether muscling through an unrelenting door schedule or cutting that last layer of topography on a steeply sloping hillside site model.

For our Optimism Design Friday, I presented Wil Srubar’s work developing carbon-neutral concrete.

I was struck by microalgae’s potential global climate impact and have continued to wonder what other hidden microscopic building blocks might hold incredible and unharnessed change potential. David’s thanksgiving email reinvigorated this line of thinking relative to our own studio – specifically the notion of our ‘AMD family.’

Perhaps this coincided a bit too coincidentally with my version of family theater over the holiday weekend, but the more I thought about this notion of family, the more its relevance came into focus for AMD. This notion of family is not meant to conjure a rose-colored sense of home and belonging. Families are anything but easy. Family suggests that we are all here for each other, through thick and thin. Families require hard work, trust and autonomy. They require many, many small intangible and thankless acts in good faith. And they require accepting each other with all of our differences and offering grace, space and the benefit of the doubt when we disagree or come up short in some way. Perhaps most importantly, families require celebrating successes and victories, no matter how significant and regardless of personal contribution. As 2022 winds down, AMD certainly has much to celebrate and be thankful for.

Thank you all sincerely for everything you bring to AMD, for your energy and passion, and your contributions to our work— small and large, seen and unseen. I am incredibly proud and grateful for our small family’s huge impact on our community. Please enjoy this fourteenth volume of 3198. Thank you to all of those who contributed.

Blanchard BenAbbey Woods

40 REFLECTIONS ON ARCHITECTURAL OPTIMISM, IN NO PARTICULAR ORDER

Stephan T. Hall

DOES A.I. HAVE A PLACE IN ARCHITECTURE?

Eric Kuhn

ARCHITECT AS CURATOR

Quinn Waites

QUIET OPTIMISM

A SERIES SEGMENT FROM SOMEWHERE IN THE MIDDLE Matt Joiner

OPTIMISM IN DESIGN IS OPTIMISM IN ITS PEOPLE

Kate Thomas

THE OPTIMISTIC ARCHITECT

Valerie Presley

THE BEST OF ALL POSSIBLE WORLDS

Paul Haack IN THE COMMUNITY

On September 17, 2022 AMD hosted a panel discussion on “Negotiation”, the third and final conversation in a series of events organized by NOMA’s Education Committee. The panel was moderated by Jennifer Lozano and Ben Blanchard, and featured four prominent architects and designers from our Denver design community: Joey Carrasquillo (Principal, AMD), Tania Salgado (Founder, Handprint Architecture), Keesh Pankey (Founder, Desibl) and Beth Mosenthal (Founder, C1 Architecture + Design). The conversation provided valuable insight into the fundamental goal of negotiation, helped unpack some of the toughest and most persistent challenges that many minority architects and design professionals face, and offered practical tools coupled with first-hand experiences to help the audience advocate for themselves moving forward.

AMD was honored to support the second annual lecture in the Mark Outman, FAIA Memorial Lecture Series, presented by the University of Colorado Denver, College of Architecture and Planning, Envisioning a New Public Realm with award-winning landscape architect Jim Burnett, FASLA (OJB) and learn more about Jim’s career creating vibrant and restorative parks and landscapes.

If you happened to miss the lecture, you can watch the this and last year’s full recording at amdarchitects.com/ the-mark-outman-memorial-lecture-series

Mark worked at Anderson Mason Dale Architects in the 1980’s between undergraduate and graduate school, later attending Yale University and then joining Cesar Pelli & Associates. Mark was known as a voracious reader and researcher, and the AMD studio now houses his truly remarkable and extensive book collection.

It takes a lot of optimism to be a traveler, especially post 2020. A lot can go wrong, things come up and fall apart along the way. But we plan and hope that it all comes together as dreamt. Our trip comprised of 4 countries over 14 days, and thankfully our optimism paid off. The catalyst being Oktoberfest in Munich, Germany. Images, of which, I have not included in this journal. But as you can probably imagine, it mostly involved beer steins, lederhosen and crowded tents.

For this journal I selected images I took at each destination, hoping to share my architectural lens and experiences.

SEPTEMBER 18, 2022

Our first stop, Bellagio Italy, the village jutting out into Lake Como. Our apartment was comfortable and sunny, with a 4’x4’ cut away in the gypsum board finish to expose the concrete wall beyond. Written with blue paint on that exposed square of concrete was a dedication message about the home:

“This house constructed with the help of a blessed god - a dream that has become reality for daring, tenacious will of mother seraphim.”

I tried and failed to find more information about if this type of note was standard in historic Italian homes. But nonetheless, I found it charming.

SEPTEMBER 24, 2022

We traveled from Lake Como by car, on a sunny day, through the alps to arrive at Therme Vals. The incredible mass of Swiss Alps surrounded the drive. Photographing Therme Vals from the exterior was quite difficult. The grass roof structure half buried into the hillside exposed just a peek of the Valser Quarzite slab facade to the visitor.

The interior, where photography is not allowed, was cave-like and calm. The expansion joints in the roof plane, which align with the baths on the interior, let streams of light through. The perspective is always controlled and layout of the vertical stone slabs either allows or denies the view to the exterior.

“The meander, as we call it, is a designed negative space between the blocks, a space that connects everything as it flows throughout the entire building, creating a peacefully pulsating rhythm. Moving around this space means making discoveries. You are walking as if in the woods. Everyone there is looking for a path of their own.”

-Peter Zumthor

SEPTEMBER 24, 2022

The warmth of the oak clad Thom Mayne hotel room was our retreat from the quartzite baths. The 215 SF room, along with the Ando, Kuma & Zumthor rooms, were completed as part of the 2016 interior retrofit to the existing building.

At the heart of the room is the double-curved, fritted glass shower piece designed by Morphosis – a sculptural object that stands in glowing contrast to the room’s natural surfaces. Admittedly, the beautifully curated space was spoiled by my suitcases sitting out with nowhere to tuck them away.

SEPTEMBER 29, 2022

Our day trip to Salzburg was defined by historical walking tours, funicular rides and neck craning photography. The narrow and winding streets of Salzburg’s historic center are lined with 17th and 18th century churches, houses, gardens and fountains erected in the style of the Baroque and Italian Renaissance.

The predominant architectural notes were the balance of robust, monumental forms with intricate adornments and glazing.

Right: Collegiate Church

Below Right: Franciscan Church

Below: Salzburg Cathedral

1. Generally speaking, Architecture is more accessible to more people around the world than ever before. We still have a long way to go.

2. Most people still don’t know what architects actually do. Revel in the opportunity to teach and inform.

3. More often than not we are put into roles where we get to listen and learn, it is imperative we do so.

4. Architects are required to move fast while projects go slow. This dynamic sometimes creates opportunity to guide clients toward greater impact and to making informed deliberate decisions while other times things don’t materialize this way, regardless our responsive efforts remains a crucial ingredient.

5. Our industry and clients will increasingly demand building all wood structures - CLT + Glu-lam timber buildings. Embodied Carbon goals are key to tipping the scales on this conversation. We’re not late to the game, there’s no need to have done it first, but strive for better, with care and tenacity. AMD is poised to have an all-wood structure built in 2024, with the Northglenn City Hall and another potential hybrid wood structure with the Westwood Rec Center.

6. The very real concern that we are not doing enough to stem climate change, has and will continue to drive us further to better our planet and evolve industry practices.

7. More clients are demanding high performance sustainable buildings. Even in regions traditionally thought of as moderate or ‘conservative’.

8. The message of ‘a Net Zero Building’ is simple and understandable (produce as much renewable energy as you consume.) It is a gateway to more nuanced and productive client conversations and goal setting.

9. The necessary, if challenging, conversations around DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) continues to be embraced with interest across many industries and organizations. For those organizations that are committed, the conversation will evolve and will be backed with initiative and actionable strategy.

10. The technology, production and tools of our industry will continually evolve to include exciting new capacities and techniques, but the technological evolution to-date has not replaced the fundamentals of our profession, on the contrary if anything they have reinforced the need for strong architectural frameworks and underpinnings.

11. Advanced AI (artificial intelligence)- at least for the foreseeable future - will require human experience and intuition to wield its potential.

12. The results of our work contain tremendous stories. It is a pleasure and privilege to curate, record and communicate these stories.

13. In a world of devolving credibility for many social media ‘influencers’, architects that have built and maintained their authenticity around substance and achievement continue to remain competitive. This does not mean short term marketing pitches from less than authentic firms don’t win out in the short term. Nor does this mean one can neglect strong marketing strategies and tactics, rather, authenticity is fuel for a firm’s brand to land with lasting credibility.

14. Trust, authenticity and track record is a most valuable asset. We build this collectively within our firm, where the final detail and project execution is as critical as the marketing narrative that reels in the project.

15. We can take pride in our authenticity and in the humility it takes to do what we do every day

16. We know how to enjoy a good meal, to a delight in a well crafted environment, to imbibe with good people. These are no small things.

17. We search for delight, serendipity and joy.

18. We could have to told Zuckerberg the Metaverse is no substitute for real connection to place and real connection to people. These are fundamental objectives of architecture because they are foundational to our evolution as humans.

19. Program. 20. Context. 21. Craft. 22. Character. 23. We know how to listen.

24. We hear and empathize with what clients aspire to achieve.

25. We inform clients what they can afford.

26. We are provocative and creative in discovering and delivering what clients cannot live without.

27. We cannot help but get lost in deep observation and research. The trick is shifting gears and knowing when the search must be pointed, productive and relevant.

28. We can take our work seriously but don’t have to take ourselves too seriously.

29. Our profession has a long memory and heritage. It’s a unique privilege and responsibility to pass along and receive such mentorship from collective memory.

30. We can look for good moments of architecture everywhere and at all scales, from a humble home to a new civic center.

31. We travel. We appreciate the privilege and delight of experiencing the world around and doing it with those closets to us.

32. At our best we are united by the most challenging of design problems and constraints.

33. While we need focus and solitude, we cannot work on an island.

34. We are fortunate to work in a profession predicated on gathering people in physical space.

35. Our client and collaborator relationships are forged, not over days or even over months, but often over years. When done right and served well, we have increased our own personal capacity for human connection, perhaps the greatest achievement of an architect over ones career.

36. We are inspired by the creativity and talent of the individuals in our firm.

37. Design-Build may be gaining traction with some clients / institutions, and although we have proven to be as competitive as most with this delivery method, there’s just as much likelihood that the pendulum will swing the other way.

38. Architecture is hard, but we’re not doing surgery here. Enjoy it.

39. Success in architecture can sometimes feel allusive. But time and time again it has proven more readily afforded to those (individuals and firms) who believe they can do hard things.

40. Effort, time and caring deeply are not-so-secret ingredients to doing hard things. As a firm, we are fortunate to share these burdens and successes.

At 2022’s Colorado State Fair in late August a piece of art was evaluated and given first prize for Emerging Artist: Digital Arts/Digitally Manipulated Photography. Jason Allen won for his piece, titled “Theatre D’opera Spatial”. The print depicts an expansive space, lit by an otherworldly circular window, ornately detailed walls and characters draped in what might be Victorian dresses. The scene is striking for its visuals, but it’s also striking in its origin – typed characters into an A.I. interface.

Théâtre D’opéra Spatial by Jason Allen. Made using A.I. Text to Image Generation.

Théâtre D’opéra Spatial by Jason Allen. Made using A.I. Text to Image Generation.

That win has sparked a backlash questioning the role of A.I. in creation, digitally and beyond. The New York Times, the Washington Post, NPR, Smithsonian Magazine, the local 9News – all of them and more featured articles to spotlight what seems to be a turning point in the collaboration between A.I. and designers. They also spotlight the ethical boundary of a tool that may be too new for some to understand, and therefore ripe for misuse by those willing and in the know.

The ethical debate is interesting and important, particularly to those of us working in a field based around intellectual property and copyright. AMD’s drawings belong to AMD, usually in perpetuity. Their design expressions, while open to public view, are fine serving as inspiration, but it would be unwise for someone to rubber stamp a facsimile of any particular pieces outside of the context in which they were conceived and now exist in. As designers, we might

be flattered to have a unique design feature influence a neighboring work, but the term ‘rip off’ comes to mind if it crosses into the realm of a copycat.

Called ‘MidJourney’, the cloud based A.I. platform Allen used was created from a massive database of images, tagged for the program to pull from, hybridize, iterate on and stylize to a user’s desire. It can create images, in a matter of seconds, of animated characters, realistic landscapes, futuristic paintings, or all of those at once – it simply takes experimentation with different text prompts. Tea party on mars…done. Same tea party but styled a la Monet? Also done. Not quite right? Hit the variation or redo buttons for something more to your liking.

While MidJourney seems to be the most popular for its realistic and striking image results, it competes with other A.I.-to-text platforms as well. Chief among them Open A.I.’s site ‘DALL E2’ and another called ‘Stable

Diffusion’. The community who uses them seem to say similar things, that MidJourney is sleeker, easier, and ‘creates’ more while DALL E2 is the more powerful, albeit less user friendly interface, allowing for more editing of the minutiae. Stable diffusion seems to create less artistic imagery with cleaner lines, but is just as powerful. All of them offer affordable subscriptions (think a monthly streaming service) and are open to anyone willing to use. And while most of the creators out there are creating for the pure pleasure of seeing words turned into visuals, others are creating artwork for sale, comics for download and inspiration for future worlds.

Within our own industry, particularly architectural visualization, the possibilities seem exciting. While some of the most striking imagery of architectural creations shared by creators like Hassan Rabab, a computational designer and construction industry professional are fantastical enough to be beyond the possibility or expense

of the present, others could be stepping stones to built designs.

Once your text prompts spit out something you know to be on the right track you can iterate (a verb most good designers are familiar with) almost infinitely. Architectural design often involves iteration – in sketch, model, rendering, mockups and drawings. It also involves the use of language to spark and guide ideas into being. Could designers who put a high price on authorship lean into a tool that is the ultimate thief – borrowing from millions of images to help create something new? Like most new tools, I believe the answer exists in the rules you create for yourself.

Architects and Designers of the built environment vary wildly in how they get from point A to point B, from project conception and design to detailing, construction, and eventual building use. Practitioners hone their skills

A DETAILED PHOTOGRAPH OF THE FACE OF AN ARCHITECT WEARING THICK BLACK PLASTIC GLASSES, REALISTIC PORTRAIT PHOTO, BLURRED BACKGROUND.

over the entirety of their careers. From the time fingers picked up a pencil to the time they get super glued in the model shop, from strained eyes drafting details to honed eyes in the field. Designers build skills and gut feelings and routines largely by observing what has come before – a drawing, a building, a plaza, a mindset – and improvising, and sometimes, although frowned upon, by outright plagiarism.

Context and originality converge with the tried and true to bring vision to reality. Avant-garde is rarely avant-garde anymore in the age of global social sharing and learning. Even the smooth curves of a scripted NURBS model responding to a climatic meta-data driven formula is built on a language repurposed from a predecessor. Within the spectrum of design creativity, we rarely see black and white, true original or true facsimile. Generally, we live between them, in the world of moderation, compromise, and balance.

How do we evaluate a process like Text-to-Image A.I. that samples seemingly infinitely? If it can take as many inputs as we can throw at it, iterate constantly and on top of it all – learn – how do we create rules for ourselves that honor the authorship of others when you’re not sure who the author is? That’s the exciting part – you have to use it. Again, you set rules for yourself based on the same ones that have guided design prior to the tool’s incorporation and then you put on your helmet and you go for a test drive. As a tool that could be given text and visual prompts it certainly would be a stretch to expect the socio-political, economic, and largely human issues of place to be part of the formula it uses to spit out images. And so it remains the responsibility of the user to recognize context – to use the tool as a tool, and not as a designer of the built environment.

As a designer excited about these tools I wanted to test them out – first and foremost to understand how difficult it may be to use, and evaluate what kinds of bias show up in these tools. I asked MidJourney to imagine a number of architectural prompts. I was curious how a system that is curated from web images would imagine an architect; or an ‘starchitect’ inspired interior; or more loosely “an architect’s playground.”

Often the collection of imagery comes from a western, WASP-dominated database. The first image set was created with the following prompt (along with some qualifiers to tell the system what aspect ratio and quality to render the images): “a detailed photograph of the face of an architect wearing thick black plastic glasses, realistic portrait photo, blurred background”.

It was created without any text indicating the architect’s race, sex, or age. And yet, it gives us four options of a middle-aged white male with graying hair. So I prompted it in the same way but asked for a female architect. The results are equally white, and it clearly thinks, wrongly or rightly that the profession often ages us with salt and pepper styling.

Another thing of interest. You can see that of the images available there seems to be one that is influenced by a copyrighted Shutterstock type image where watermarking text was picked up on. This begs the question of authorship, intellectual property, and copyright. We as designers often start with precedents just as these AI tools do, but how difficult is it for the AI to set a boundary where source material remains a source and not the end-product, blurred or tweaked with little noticeable differences from the original.

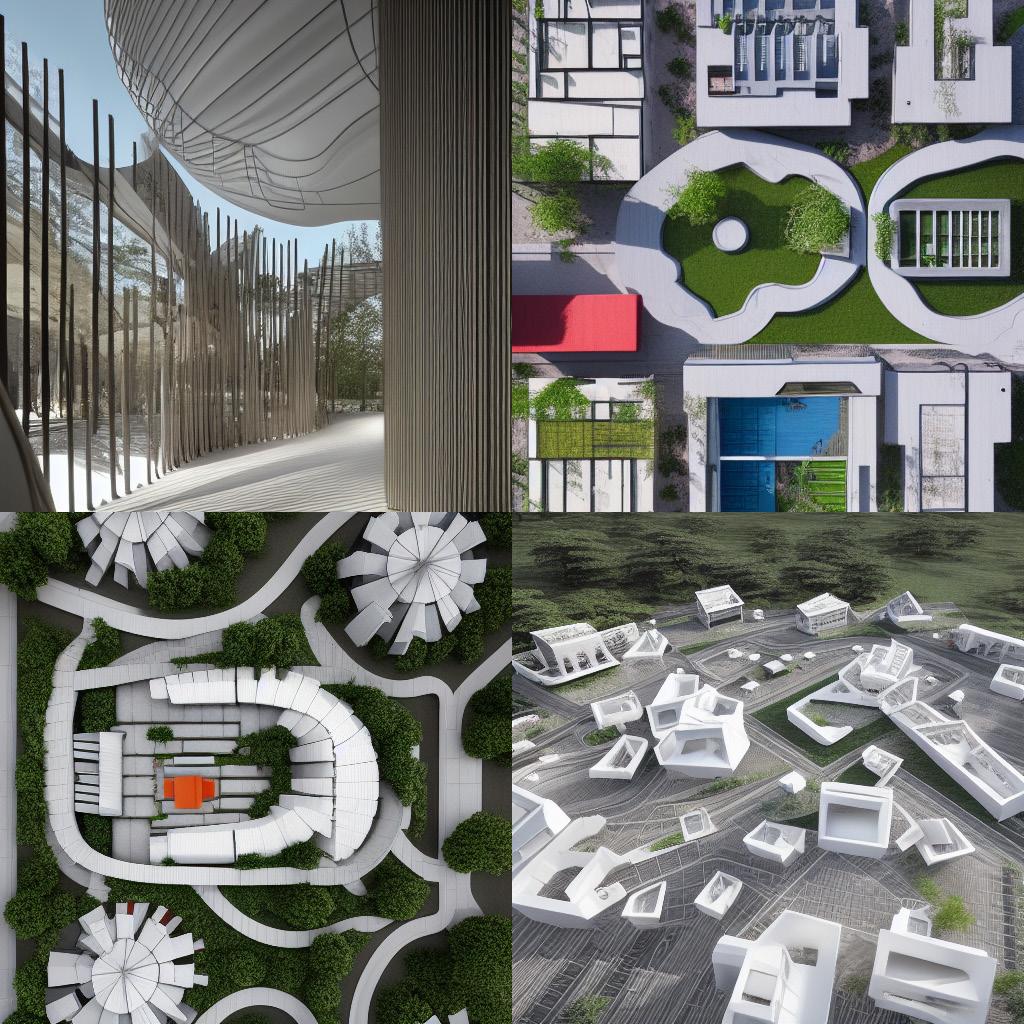

A ZAHA HADID ARCHITECTS INSPIRED INTERIOR SPACE, HYPERREALISTIC, OCTANE ENGINE, 8K DETAIL, TROPICAL PLANTS KITCHEN ROOM WITH SKYLIGHTS, OCTANE RENDER.

Walter Benjamin – a philosophical foe of Martin Heidegger – wrote in his 1936 essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ about the aura of an original. He argued that ‘even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” I won’t delve deeper into the phenomenological theories of the aura of the original but will say that fakes tend to be ‘you know it when you see it’ objects. It will remain the onus of the users to moderate what goes into AIs and what gets distributed from their outputs – it’s a responsibility that comes with many tools, but particularly one that borrows its inspiration 100% of the time.

The next imagery I’ll share is of the ‘starchitect’ inspired interior space. The prompt was: “a zaha hadid architects

inspired interior space, hyperrealistic, octane engine, 8k detail, tropical plants kitchen room with skylights, octane render.”

You’ll notice after the first clause that I asked for certain styling, then went on about the rest of the image and came back to the ‘octane render’ again, which is a rendering engine with a unique style that many users use in their prompts. I thought it would fit with the Zaha styling. In my opinion, the images are fantastic – creative, architectural, realistic, and I think, quite beautiful. If you were leaning towards a Singaporean model of futurism I think it would be worth doing some additional iterations and then begin thinking about how to design a working model.

The last set of images are more playful, less strict, and crafted using only three words: “An architect’s

An Architect’s Playground. Made using DALL E 2 A.I. Text to Image Generation.

An Architect’s Playground. Made using Stable Diffusion A.I. Text to Image Generation.

playground.” Because of the broadness of the prompt I wanted to reuse it, verbatim, in the two other AI Text-to-Image generators. The first foursome is from MidJourney, the next from DALL E 2, and the last from Stable Diffusion. You’ll notice the starkly different ways each has envisioned the playground.

With some practice, users can hone their prompt writing skills to insert the context and authorship that can push outputs beyond collage and copycatting. Without a doubt there will be hurdles to ensure AI’s proper usage, but the hope of this author is that the tool pushes designers to

imagine in new ways and to augment their design process, not skip other valuable steps along the way. Let’s play in the sandbox for now. Whether the sandcastles will stand or crumble is still yet to be seen. Personally, I’m optimistic they can be built with robust enough ideas to improve our architectural landscapes, not imperil them.

An Architect’s Playground. Made using MidJourney A.I. Text to Image Generation.

AN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN BUILT ON PROGRAM CONTEXT CRAFT AND CHARACTER A PROCESS OF EXPLORATION ITERATION AND DISCOVERY WITHIN WHICH UNIQUE AND TRANSFORMATIVE OPPORTUNITIES ARE REVEALED NURTURED AND INTEGRATED INTO A COHESIVE WHOLE WHERE THE VERNACULAR OF ARCHITECTURE IS ROOTED IN TECHNIQUES AND TRADITIONS OF ELEGANCE AND COHERENCE THROUGH THE CAREFUL CONSIDERATION OF MATERIAL SCALE PROPORTION PERFORMANCE AND HIERARCHY WHERE DIMENSIONS OF LIGHT TEXTURE COLOR AND SOUND LEAVE RESONANT AND MEMORABLE PLACES OF INDELIBLE DESIGN, ARCHITECTURAL SKETCH STYLE

AN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN OF A BUILDING BUILT ON PROGRAM CONTEXT CRAFT AND CHARACTER A PROCESS OF EXPLORATION ITERATION AND DISCOVERY WITHIN WHICH UNIQUE AND TRANSFORMATIVE OPPORTUNITIES ARE REVEALED NURTURED AND INTEGRATED INTO A COHESIVE WHOLE WHERE THE VERNACULAR OF ARCHITECTURE IS ROOTED IN TECHNIQUES AND TRADITIONS OF ELEGANCE AND COHERENCE THROUGH THE CAREFUL CONSIDERATION OF MATERIAL SCALE PROPORTION PERFORMANCE AND HIERARCHY WHERE DIMENSIONS OF LIGHT TEXTURE COLOR AND SOUND LEAVE RESONANT AND MEMORABLE PLACES OF INDELIBLE DESIGN, PHOTOGRAPHIC REALISM, HIGHLY DETAILED, 8K, OCTANE RENDER

Within the architectural industry the principal act of the architect is universally called design. To design or be a designer is thrown around casually to describe the act of forming spaces to people’s needs. Though this term carries certain baggage with it that should be addressed. A reframing is in order, for how it impacts the perceptions of lay people as much as the architect creators.

Definition of design - do or plan (something) with a specific purpose or intention in mind. - an arrangem ent of lines or shapes created to form a pattern or decoration1

By definition, design deals with creating objects from a narrowed: specific: selection of ideas. A practicing architect does this at times, however design via definition is experientially limited to those factors which it addresses or those ideas it uses as fodder.

As is, the act of designing encompasses all that an architect does when framing space. Though it is hard to claim that Architecture, is itself specific; the experiences one person has in a space vs. another are necessarily different. An apparent gap emerges here, between what is done, “designed” and what is experienced, for the concept of design doesn’t suggest an experience, rather it suggests an end product... Moreover, the term “design” has no universal verdict upon which its finished state describes.

In effect, designing is problem solving, whereas curating is “piece organizing”. Architectural space should not be seen as a solvable problem, for if it is, the poetic: sensory: narrative[s] of the space are easily lost to the burden of the more intractable parameters. We curate for experiences and design for problems.

The act of curating is highly experience driven. A curator curates principally for an exhibition. A curator chooses the paint, the way the text looks next to the pieces, how the space is organized, what the graphics look like. They are composers of experience. They work with what they have (a space and pieces) to achieve a specific purpose (an exhibition).

It is then, not a stretch to say Architecture could be a curatorial act, as all public Architecture functions as an exhibition of sorts and is itself a type of exhibitionist medium. A building opens and it closes— is no longer occupied or torn down— not unlike an exhibition.

Curating engages the preparation of an environment for things to be shown. To curate something is to think about the interrelationships between objects...

Design deals principally with organizing ideas based off their qualities, while curation deals principally with organizing objects on the basis of their ideas.

And what is the purpose of design, if there is no universal ending place of the designed? Design tends to emerge from the interval between the observation of lacking2 and the faith of an absolute solution. Importantly, there is nothing in those notions that suggests that people may design appropriately for others.

In fact, one could design things to intentionally separate people, such as border walls or prisons. Thus, the health of a society is effectively toned by the experiences and values of the designers and “architect designers”— curators.

The value of design comes from its relevance to the public, but what the public values cannot be adequately established without the creation of objects for them to engage. Thus, the spirit of a design is its solvency.

This “lack” that design attempts to resolve, posits: catalyzes: how that absence evolves: matures. There is a responsibility and implicit moral gravity to the designed object, as all the products of design effectively direct their participant: viewers: psyche towards some few things. Good design then, aims to both resolve problems and suggest additional social instruction. To condense this reflection— the only reason one should design, is to right the existing societal imbalances.

Curation too, aims to right existing societal imbalances, via the optimism of putting forth new experiences in an exhibition.

On the micro scale, design addresses inequity: absence: while on the macro scale, curation addresses the nature of an experience.

Shifting the perspective to ‘Architect as curator’ puts the architect in the role of a selector. Curating is also more transparent about the act of arranging pre-manufactured objects, as an architect principally does with windows, wall types and doors. Whereas ‘architect as designer’ suggests that solving the problem, starts from a zero ground and returns to a zero ground when completed, which is never the case, as making— “designing”— something always deals with referencing other things, such as the hand, eye or foot.

Moreover, design suggests a clarity in the generated object or space, which most often cannot actually be fully known by the “designer”. To call oneself a curator, puts one in the role of sculpting experiences, in a way that is empathetic to the experiences themselves. In another sense, design suggests that there is a “right” experience to have, while curation suggests that your being present is the only prerequisite to the validity of the experience.

Objects that directly interface with the human body are appropriately described as being “designed” for how they impart an obligatory direction on their participant. The designed object in space, is however, curated, for even though the body may directly interface with it at times, it is in most instances, not in immediate proximity to be engaged with.

There are very rarely spaces which could on their whole be considered “designed” as the architectural industry on the whole engages with a market of manufacturers that provide them with readymade objects. Those manufacturers function as the designers and the architect that chooses them, the curator.

There are points when architects may step beyond their role as a curator— they may request modifications to manufacturer’s products, but this is often more of a collaborative process than a solitary design on the architect’s part.

Definition of curate:

- select, organize, and look after the items in (a collection or exhibition) - select the performers or performances that will feature in (an arts event or program)3

Curation is itself an explorative act, it’s more open ended than design in the number of interpretations it produces. And though there is a definite point of an exhibition, it is widely understood— due to the design of museums— that people may wander through a gallery or enter it from another entrance.

Life and the experience within buildings, is inherently imprecise— living in a multiplicity of meanings— while design is very singular minded, as it is aimed to fit a solution. Specificity in the sense of designing is holistically unfit for buildings, as the more specific something becomes the less universal it also comes to be.

When you speak about architecture as curation, you’re acknowledging the “objectness” of the features that exist in a building. In the case of designing a door-handle, the hand is part of the design, as the handle has to fit the hand to be functional; but when “designing” a room, a hand is part of the body and not necessarily part of what is important to be “designed” in the room; you could

“design” a room for the hand, but the result may be a room that is not suited for the eye or foot.

It is unhealthy to think of buildings: spaces: as products: objects: as they are more dynamic: multi-faceted: than objects are, necessarily because a space is filled with objects. Like a Matryoshka doll, an object always sits within an environment, thus a building could only be seen as an object from the outside, not from the inside.

There is a sense of authority that comes with being a designer vs being a curator. A designer has a more active positioning; the designer makes the designed and the designed is nearly always seen with reference to the designer. In the case of the curator, the curation, is more about the curated and the curated for, than the curator themselves. This distinction is key in clarifying the role of the architect in framing space.

experiential. ideological. Another reason why curation should be used to describe the functioning of the architectural process is how it focuses the process of creation on the experientially driven nature of the space, as opposed to the ideological nature of design; this helps clarify to the architect and the public what the role of the architect is... to focus space though objects.

The experiential aspect of a final design could easily be lost in the process of working through the parameters: problems: of the project, such that you have a “designed” space with a prosaic or dull experience.

Design is too broad a term to describe the activities of an architect, for they neither make every object in a space, nor could they possibly think of all the possible outcomes of “designing” space. By approaching architecture as curation the experiential aspect of a final design is described more authentically as being nebulous. Moreover, the work doesn’t claim to be a narrow solution to a complex problem, instead a single out of many possible solutions.

1. Oxford English Dictionary

2. where lack is a function dependent on one’s experiences and values

3. Oxford English Dictionary

The most remarkable compliment I have heard given to Sage Living, came from a developer touring the facility with the builder, showing some of their recent work.

In the history of great architectural compliments, this might seem… underwhelming. If you are unfamiliar with assisted living projects, you could even think it was a knock. But to anyone who has designed care for the human population reaching the end of their lives, this kind of compliment should sound more like a triumph.

It is a quiet compliment, and it aligns appropriately with the story of Sage Living and how it came to be. From somewhere in the middle of an architectural career, this is a project story written from both my observation and participation — I joined the design team in design development and ultimately saw the project through construction. It is a story of optimism about some uniquenesses in how Sage Living came to be.

It is a generally optimistic subject to write about senior housing, end of life care, memory care, overcoming ageism,… all under an architectural filter. Architecture has such a powerful role to fill in these aspects.

When many of us recall visiting a senior living facility, the memories are vastly closer to institutions than housing, let alone living. I recall from my experiences visiting my grandparents the hard and plastic surfaces that describe the feel of the furniture as much as the walls and floors. I recall the quietness and stillness, like walking through an uninspired gallery of muffled time – the real emotions

must be pushed somewhere hidden away, unable to thrive on the bland, cleanable surfaces. Is there anything about this community that felt like home inside? It seems a desperate reach for me to recall any feelings that resemble or recall home from the environment I experienced. I have to guess that my experience is not rare and it is a reflection of many influential factors that architecture plays a part. Healthcare, not residence, is the dominant sphere of influence on senior living, which has particular influences on architectural decision making.

Healthcare is an incredible sector for architecture, harnessing the power of healing in spaces for care and repair, with systems and infrastructure, and interwoven with common design principles of space as well as less frequently utilized like biophilic connections to nature. In many ways healthcare design is an immensely complex problem to solve and it is no wonder many architectural practices specialize in it. It is no no wonder healthcare systems look to those practices with experience. In their eyes, a facility that works to the best of it’s ability means better treatment, seeing more in-need, and in the most extreme case, the difference to save a life. In the case of assisted living and memory care, a facility that works to the best of it’s ability might add numbers of days and make the quality of each of them as high as can bequantity and quality.

I was not present with the AMD team interviewed by St. John’s Health to earn the commission to design Sage Living. AMD does not have a deep history of designing assisted living facilities, maybe not even much housing at time - certainly not what we do now - and healthcare is not a sector I’ve known the office to compete in at all. What were we doing there then?

The logic of an MEP firm acting on-call for the hospital seems logical. The engineering systems of a health campus are already complex and logically in constant need of assessment. CatorRuma has overlapped with AMD on many projects, including many today. My understanding is that CatorRuma connected AMD with an opportunity for senior housing and a medical office building. The hospital had been long-served by a firm, Earl Swensson and Associates, with deep national healthcare practice. The relationship had evolved into frustration as the hospital felt it was not really being heard. We were introduced as a practice seemingly completely the opposite – natural listeners with a very limited healthcare practice. David Pfiefer and Paul Haack made an impression on the hospital’s staff and CEO to the extent that they were enthusiastic to hear from us.

In a recent conversation, David recalled bringing Paul onto the project after meeting the hospital with an instinct that Paul would bring a narrative and craft to conversation that the hospital had never experienced. Paul has long expressed that the program is a proposition, perhaps the most important design decision that can be made in establishing a project’s enduring lifetime. Indeed, along with former colleague Beth Mosenthall and assisted living consultation from another close contact, Bill Brummett, the team listened and conversed about the character of care to develop a program that developed through iteration and exploration.

Do you remember the compliment mentioned at the opening? It was in these early impressions that designing for dignity could lead to the best possible outcome. The AMD team brought ideas to differentiate housing for seniors with principals of community, suggesting repeatable spaces called “neighborhoods” outside a small cluster of resident rooms. These spaces allowed

something in between the private rooms, and fully common spaces like a town hall and shared living room. Designing for dignity could mean breaking down the sterile and institutional environments most commonly associated with senior living and care.

The hospital agreed this was compelling, and design of Sage Living began.

This is only the beginning of the optimistic story of Sage. The designs and iterations that ensued are numerous and full of aspiration and hope and curiosity. The exploration of program is a constantly evident. It may be felt in some conversations that what was ultimately constructed as Sage is only a fraction of what was imagined – what could have been. As the design team would soon begin to realize, institution in healthcare is deeply rooted. Achieving a vision of space to match the ambitions of the design team and the hopes and expectations of the owner would be met by challenges at every phase including

typical construction team antics, but adding unfamiliar and deeply entrenched healthcare industry forces that have an effect of becoming literal barriers to constructing anything but the prevailing typologies. I can dig more deeply into that story on a future issue of 3198 aiming for a less inspired and more practical tone, perhaps examining external spheres influence the practice.

On April 16, 2016, there was a 7.8 magnitude earthquake with several severe aftershocks in the coastal Manabí province of Ecuador. The earthquake killed 700 people and left more than 6,000 people severely injured with 700,000 in need of assistance. Approximately 35,000 homes were destroyed or badly damaged, leaving more

than 100,000 people in need of shelter. Water, sanitation, and healthcare facilities were also destroyed, totaling to 90 percent of infrastructure destroyed in some areas (worldvision.org). However, nearly all the infrastructure constructed of bamboo in these areas remained standing, largely unharmed.

Below: 7.8 magnitude earthquake aftermath in Manabi, 2016

Bamboo is local to the coastal regions of Ecuador and has been used as a building material traditionally in this area for thousands of years. This makes bamboo building in these regions both affordable and accessible. A community of many skilled maestros build this bamboo city together. Here, there are expansive forests of caña guadua bamboo, the species most commonly utilized for building. Not only is Guadua abundant, but has a much smaller environmental impact than wood building, and is stronger in the environmental conditions of this region. Guadua “has rapid growth and higher productivity, when compared with trees. Usually, the growth cycle of bamboo is a third of that of a “tree of rapid growth” and has double the productivity per hectare. Compared to oak, Guadua even produces up to four times more wood… The bending strength of most bamboo species varies between 50 and 150 N/mm2 and is on average twice as strong as most conventional structural timbers…it also captures CO2 and converts it into oxygen, 35% more than regular trees” (guaduabamboo.com). Guadua buildings are immensely strong in earthquakes due to their tensile strength and lightweight flexibility, making these structures incredibly resilient in these regions. However, before the 2016 earthquake, most larger buildings in the area such as schools and civic buildings were being built using more general practices and materials despite accessibility to bamboo and skilled builders. The damage of these public spaces continues to deeply affect these areas.

It is important to note that it would be naïve to believe that everyone in the community has the ability to hire a bamboo maestro to rebuild their home. While bamboo building is both affordable and accessible in this location, people in this area tend to build in the least expensive way possible with what they have or can find when working on this smaller scale. This is why organizations like the following are so important for rebuilding these homes. In July of 2019, I traveled with a group of students to study with the Regeneration Field Institute (RFI) at Los Arboleros Farm, a 71.5 acre organic tropical farm in the rural agrarian community

of Chone in the Manabi province of Ecuador. RFI was created “to streamline bamboo production, processing, distribution, and construction to make sustainable building an accessible option in coastal communities and generate local jobs” (regenerationfieldinstitute. com). In coalition with local reforestation, climate justice education, and programs working towards becoming an “Eco-City”, RFI has formed the Bahia Beach Construction movement. This movement aims to donate economically viable and seismically safe homes to families in the most vulnerable areas that were affected by the earthquake. RFI partnered with Los Arboleros Farm in November of 2017 to introduce global student learning and job training into this reconstruction. Los Arboleros is an organic farm utilizing regenerative farming practices such as compost making, crop rotation, agroecology, topsoil conservation, and watershed management (regenerationfieldinstitute.com). RFI and Los Arboleros Farm are reconsidering the site and utilizing all their local resources as a solution to rebuild. These organizations utilize the people of the community and the bamboo grown regeneratively on their farm to create jobs, provide displaced peoples with new homes built to last, and to reunite this immensely beautiful community after such a traumatic event.

This aids local economies by reintegrating traditional and resilient building into these communities. These organizations, cultivated and owned entirely by locals, utilize the optimism of their people to rebuild. When design has the intention of optimism, the results resound in multiple areas within a community, not just within the scope of a site. Local materials and artisans are utilized. The site is home. The designers are the client.

Take in contrast, the relief shelters that were provided for these areas by Quito, the mountainous capital of Ecuador. Many still scatter these areas today; they are strong, affordable, and accessible. However, they are made almost entirely out of sheet metal, which in Quito would likely be successful. Although, in these coastal regions, it is much hotter. The people of these communities are

WHEN DESIGN HAS THE INTENTION OF OPTIMISM, THE RESULTS RESOUND IN MULTIPLE AREAS WITHIN A COMMUNITY, NOT JUST WITHIN THE SCOPE OF

Los Arboleros Farm in Chone, Ecuador

Los Arboleros Farm in Chone, Ecuador

Typical structure of coastal Ecuadorian bamboo home.

Aside from the foundation, every piece of the home is constructed of bamboo cut in different forms.

not even able to stay in these relief shelters for an hour because they get immensely hot. These shelters are scattered around the region, abandoned. Contrarily, Shigeru Ban designed relief shelters that were sent to the area made of paper tube walls, grass roofs, and beer crate foundations (a material readily available in the area). Shigeru Ban and RFI gave extra care to give compassion, listen, and understand.

This is thoughtful design. These communities rebuilding their home the way it was meant to be built the first time is passionate design. Using community as the greatest tool is inspirational design. Sometimes, forward thinking in building can involve reevaluating modern

building practices and connecting back to the site more traditionally with grass roofs or bamboo structures. Or it can be taking the care to learn deeply about the communities we are designing for and the specific needs they may require. It is inspiring to know that in many cases, we as designers already know the solution to the problem, we just need the intention of understanding. A mindset of optimism.

www.worldvision.org/disaster-relief-news-stories/2016ecuador-earthquake-facts www.regenerationfieldinstitute.com

Left: My student group at Los Arboleros Farm

Below: Bus stop bench my team built during our stay at Los Arboleros Farm

Valerie Presley

Valerie Presley

It is an act of optimism to be an architect with eyes wide open. To know that building material accounts for half of global solid waste generated in a year. To learn this volume is expected to double to 2.2 billion tons by 2025.

To read the amount of man-made mass has reached over 1 trillion tons, exceeding the biomass of the entire natural world. To personally acknowledge that architectural outcomes are both constructive and destructive.

The former requires a great deal of skill and resources. Sustainability is important until it’s not in the budget. Then, it’s a matter of negotiation.

Architects operate in a world of Noes.

“No, photovoltaics aren’t in the budget.” “Yes, that material is less harmful, but no, we’re not going to use it.” “No, that amount of community space is unnecessary.”

This is all true and yet the Optimistic Architect endures, finding opportunity in the irony of architecture, building in less harmful ways - some even advocating for change through design.

Architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury is one such architect and optimist. His design of The Friendship Centre in Gaibandha, Bangladesh disrupts building, community and cost paradigms in ways that resonate with the optimist in us all.

The project has been described as a true manifestation of Louis Kahn’s notion of “Architecture of the Land,” derived conceptually from the nearby 3rd century BC ruins of Mahasthangahr, the earliest urban archaeological site found in Bangladesh, and built of local hand-made bricks by the community the center now serves and employs.

On a shoe-string NGO budget, Kashef engineered a passive system of earth-covered green roofs, open courts, pools and walkways that are passively ventilated and cooled.

Limited funds discouraged the typical architectural response to flooding - which would have required raising the site 8 feet above high flood level. Instead, Kashef observed an existing embankment near the proposed site that with some intervention would protect the center from cataclysmic floods during the tropical cyclone and monsoon seasons.

“Very few architects in Bangladesh have taken up the challenge of working either in the vast rural hinterland or the environmentally delicate flood plains. The Friendship Centre is conceived not as a building, but as a reorganization of the ground surface, involving excavation, mounding and berming.”

(Architectural Review, Kazi Khaleed Ashraf)

Rainwater and surface run-off are collected in internal pools. The excess is pumped to an excavated pond used for fishery.

The design relies on natural ventilation and cooling facilitated by courtyards, pools and earth covered roofs. An extensive network of septic tanks and soak wells ensures the sewage does not mix with flood water.

YET WITHIN EXTREME LIMITATION OF MEANS, THERE WAS A SEARCH FOR THE LUXURY OF LIGHT AND SHADOWS, OF THE ECONOMY AND GENEROSITY OF SMALL SPACES, AND OF THE JOY OF MOVEMENT AND DISCOVERY IN THE BARE AND ESSENTIAL.

‘the best of all possible worlds’, Anne Yuxi

To the optimist, the glass is half full; To the pessimist, the glass is half empty; To the architect, it depends on what is in the glass.

If you Google the definition of optimism, you will discover two similar but different meanings. The first, “hopefulness and confidence about the future or the successful outcome of something” is the more common understanding; the second, “the doctrine, especially as set forth by Leibniz, that this world is the best of all possible worlds” is a little more nuanced yet describes accurately architecture’s unique relationship to optimism.

A cursory review of Gottfried Leibniz’s philosophy reveals that he does not mean that the “best of all possible worlds” is composed of only the best or the most hopeful aspects of a given situation; instead, he emphasizes that some aspects of the world may not seem ‘good’ or ‘the best’ in themselves but are part of a larger totality that is better than all the alternatives. His definition (I am leaving out his theological and religious rationale) cast optimism within a specific time and place construct in which the whole is greater than the sum of its individual parts. This situational totality includes things that might seem less than optimistic, but in their combination with other aspects renders a unique response to a specific time, place, and cultural context. This is why architecture is fundamentally an optimistic act.

Architectural optimism isn’t defined by wishful or hopeful thinking, nor is it realized through a myopic positivism, excluding the messy contingencies of life in support of a grand singular vision. An optimistic proposition is one that recognizes the totality of an architectural construct – the best of all possible worlds. The totality of an architectural situation addresses all aspects of architectural experience, the best as well as those not fully realized. So how do we better understand architecture’s totality? What are the guideposts along the path that lead to the best of all possible worlds and make possible architecture’s optimism? To answer these questions, we must go beyond the subjective theories of architecture and explore the concepts that are consistently present in all great work. These concepts are objective and expansive. Their validity and relevance within an architectural proposition are difficult to debate while the expansiveness of their interpretation allows them to adjust to the specific architectural situation. These indispensable qualities of architecture are its virtues – considered together they represent architecture’s essence, which is revealed through discovery, exploration, and proposition. An architecture of optimism embraces this process and welcomes the complexities of a multifaceted architecture.

Architecture, as an optimistic act, is determined by the way architecture’s essence is revealed in a project, and how a proposition fulfills the promise of architecture’s virtues. As architects we all have had occasion to dismiss buildings as bad¬ – work that did not rise to the standard to be considered great architecture. We experience a

building, and then, with the confidence of a team of doctors recognizing an ill patient, shake our heads and agree that this building is, in fact, ill – it is not a great example of architecture. We offer a few known symptoms of what typically ails the building and a prognosis of the things that might have worked better. How do we come to this realization? What is it about architecture, its universal quality, that enables us to render these verdicts? The answer lies in how well a building embodies architecture’s virtues and the unique ways that those virtues are revealed through built form. To put it another way, there is a consistent set of aspirations (its virtues) for great architecture that are brought forth by architecture’s unique totality (its essence); it is the architect’s task to adhere to the former while discovering the latter. It is this task of architecture that makes it an optimistic act – its final result is not based on hope or confidence but on the realization that the ‘best of all possible worlds’ is one that addresses our specific situation in its totality.

When we think of being in the world (dwelling), we do so in the hope that we are always aspiring to something better, richer, or more profound; that is an optimistic undertaking. It is architecture’s essence – its virtues –that determine the extent and success of that optimism. Unlike values, virtues are objective aspirational goals that are unique to architecture. They are the qualities, that to some degree, are present in all great work. Some may be more completely formed than others, but it is the presence of all virtues that determines architecture’s totality and the pursuit of this is where architecture’s optimism resides.

For me, there is a consistent set of concepts that represent architecture’s virtues. Collectively they create a framework for architecture’s optimistic purpose. Life-enhancing, Appropriateness, Coherence, Wonder, Humility, Joy, Authenticity and Slowness are architecture’s virtues. Of course, there are many other aspects of architecture that come into play when designing a building; however, I believe that these are the universal aspirations that give architecture its optimism.

Perhaps the most important virtue of architecture is that it must be Life-enhancing – the very term embodies an optimistic outlook for architecture. Architecture ought to celebrate the specific rituals of life as well as an avenue to newer realizations of the human condition. Lifeenhancing architecture speaks to both the nature of the specific situation and the unknown possibilities of a more profound proposition related to that situation. It is the ‘what is’ and the ‘what can be’ of a meaningful proposition. Le Corbusier’s La Tourette, Kahn’s Salk Institute and Van Eyck’s Orphanage in Amsterdam are wonderful examples of how architecture can rise above the expected and give purpose and meaning to the people that experience these buildings.

Whether at the scale of the city or at the smallest detail of craft, great architecture exhibits an Appropriateness that connects our proposal within a larger architectural scheme – incongruities and contradictions are the exceptions rather than the rule. Appropriate architecture avoids whimsy; it seeks to ground our work within a larger context.

Giving purpose and meaning to those that experience these buildings

Connecting design to something greater than itself

A general way of fitting in

Inviting us to dwell and imagine new possibilities

Rather than asking if something is novel or exceptional, architects ought to ask whether their proposition is appropriate to the given context and task. Admittedly, it is a humble exercise; however, it is one that connects design to something greater than itself.

Coherence addresses architecture’s need to be accessible to all who experience the building. A building should not come with a user’s manual; instead, great architecture reveals its secrets of organization and craft in a coherent manner. Coherence is a building’s order in legible form. This order doesn’t suggest ‘orderliness’ but a general way of fitting in; the randomness of a Swiss farm settlement is as coherent as the church of San Lorenzo.

Wonder speaks to architecture’s depth. The ability of architecture to draw us in, to immerse us in a layered presentation of the beautiful, the meaningful and the sublime is at the center of architecture’s purpose. Who has not experienced a great building where we are utterly captivated; the building commands our attention and engages our senses, thoughts, and imagination. The solemnity of Asplund’s cemetery, the richness of the Doge’s Palace and the mysterious fabrications of the Brione Tomb invite us in to dwell and imagine new possibilities – they fill us with wonder.

There should be Humility in architecture that avoids the bombastic and pretentious. Architecture does not need to shout to be heard – it is often the silent melody of a quiet and sophisticated building that resonates the loudest and longest. All too often architects are quick to ‘think outside of the box’ yet it is the confines of the box where architectural creativity resides. When I visit the Denver Art Museum and the Clyfford Still Museum, it is the humility of the latter that draws me in and rewards me with a far richer experience.

Joy is the virtue in architecture that is responsible for our feelings of profound happiness and contentment when experiencing a building. Unlike wonder, it doesn’t necessarily involve an appreciation of architecture’s depth or nuanced qualities but rather its immediate and visceral pleasure. An architecture of joy is uplifting; it can quickly renew our spirit. I feel this when I step around a corner and see the Empire State Building or enter Sant’ Ivo alla Sapienza or come through the forest and discover Wright’s Kaufmann House – all of these experiences are joyful and fill me with a sense of optimism.

An architecture of Authenticity connects us to experiences and realizations that are real. Whether it involves the truth in a program proposition, the integrity of a place or the honesty of the craft, authenticity grounds experience in the world of objective facts. The ersatz reproductions that populate the contemporary world turn our cities into a ‘Disneyland’ of deception in search of a false optimism. When buildings deceive, our experience shifts from the authentic to the nostalgic and both the new constructions and the original precedents they try to copy are cheapened.

It is often the quiet and sophisticated building that resonates the loudest and longest

An architecture of joy is uplifting; it can quickly renew our spirit

When buildings deceive, our experience shifts from authentic to nostalgic and both the new construction and the original precedent are cheapened

Slowness in architecture allows us to dwell. Great architecture can remove us from the distractions of the world and immerse us in a contemplative state. The Pantheon, the Kimbell Art Museum and the Farnsworth House, perched within a bucolic landscape, slowly reveal their secrets and unlock our innermost selves. Contemplation and imagination are ignited because of the profound sense of slowness embodied in these buildings. More important, slowness enables us to savor an image and store it within our architectural memory. Milan Kundera recognizes this quality in life and has put forth an existential equation that suggests that the degree of slowness is directly proportional to the intensity of memory. This is also true of architecture.

An architecture of optimism, the best of all possible worlds, is made possible by architecture’s virtues. Their composition and degree within buildings is determined by the unique architectural situation: one shoe does not fit all. The extent and form of architecture’s virtues need to arise at the appropriate time, place and in different combinations to be meaningful. This is the underlying premise of “the best of all possible worlds”.

Slowness enables us to savor an image

The Proposal, a film by Jill Magid.

This is not a film review as I have no experience critiquing it, and so no business doing so. But I will recommend it, to fans of film for architecture, art, and documentary blended with motive and mystery...

Matt Joiner

Matt Joiner

In reading, this film was not conceived as an architectural feature. Luis Barragan — or rather the architectural legacy — of Barragan, is a vehicle for an intellectual exploration of domain over the work of a creative who has passed. We learn about Barragan, his work, the transferred ownership and care-taking of his work at his direction, and then a twist in an unforeseen sale of these rights to another entity. Many layers are baked into this twist – economic, political, emotional, social – that contribute to something that appears to be both extremely bizarre and yet a scenario that could easily occur again. With only a few exceptions, the professional archive of Luis Barragan (meaning the rights to his name and work and all photographs of it – complete and inconsequential) is owned by a sole individual in Switzerland and kept completely inaccessible to anyone who’s inquired for the last 30 years.

The film builds with documentary-like foundations from which protagonist and antagonist characters begin to form around controlling that history and memory. It goes a step beyond documentary when the producer, narrator and key character engages the dynamic directly as a participant, like a chemist conducting an experiment but sans scientific method. In the process she builds an affection for Barragan’s work and also a personal disposition to be successful – this is not a neutral experiment. Magid becomes emotionally invested and the

exploration becomes a lure, The Proposal, to challenge this impenetrable barrier of access.

The Proposal raises many interesting questions about which the answers will be individual and contextual. In my mind, it does not make the case that ownership of art is good or bad, right or wrong in legal, economical, or practical contexts. It does make a case from an emotional capital, which is a fundamental of experiencing art.

I would not have heard of the film were it not mentioned to me by our own Dominika Rotarski (also in attendance). It was presented by a collaboration between Denver Museum of Contemporary Art and Museo de Las Americas, in a surprising venue right in our own Highlands: the Holiday Theater. The film appears to be available for rent on Amazon and you can read more on the film from the artists website: http://www.jillmagid.com/film.