A New View Of

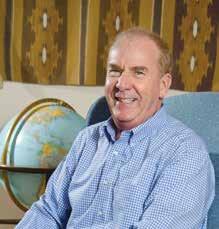

Moundville Some archaeologists are concluding that this Mississippian capital was in fact something else. By Alexandra Witze In the thirteenth century Moundville, located just south of present-day Tuscaloosa, Alabama, was one of the Mississippian culture’s most impressive settlements. It was home to 1,000 or more people at its peak, making it second in size to the great city of Cahokia. Moundville’s residents lived alongside the Black Warrior River, among at least 30 mounds protected by a large encircling wall. An all-powerful chief oversaw every aspect of community life, from scheduling the planting of maize crops to overseeing the flow of valuable goods. Smaller, outlying settlements funneled people and materials to Moundville. Such was the old view of Moundville. Now, excavations over the past two decades have led to a different interpretation of this remarkable site. Rather than a single political leader dictating everything that happened in the settlement, Moundville may have had a more dispersed set of managers. “It’s not that there weren’t powerful leaders — it’s just that it wasn’t all one chief telling everybody what to do,” said Vincas Steponaitis, an archaeologist at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill and co-editor of the new book Rethinking Moundville And Its Hinterland.

20

In fact, the leaders may not have been chiefs at all, but rather priests who wielded strength through religious influence. “Moundville as a spiritually powerful place may have been just as important as Moundville as an economic and politically powerful place,” he said. People began to settle at Moundville after the year a.d. 1000. At first they spread out, constructing a mix of buildings and earthen mounds on high ground in the river valley. But around 1200 they leveled the landscape, razing structures on high ground and dismantling and burying them in the low spots. In their place rose a new, more formal moundand-plaza arrangement, according to Jera Davis, an archaeologist at the University of Alabama Office of Archaeological Research at Moundville. “This was a tremendous building project,” she said. “The plaza, in particular, was fundamental to this process.” In 2010, researchers conducted a magnetometer study of Moundville that was one of the biggest ever done in the history of American archaeology. They surveyed about sixty percent of the site and revealed many previously unknown buried features. Davis went on to lead excavations of a few

winter • 2016-17