6 minute read

Snapshots on the Edge of Chaos

Snapshots on the Edge of Chaos

By Michael V. Pollock, Executive Director of Interaction International

Advertisement

"Boys, I know this is going to be hard, but President Kenyatta has died, and for the next three days, you can’t run, shout, or ride your bikes or skateboards outside. You can be in the yard if you are quiet, but I don’t want you going to the dukas* or out with your friends. Do you understand?”

*dukas: small shops

It was August 1978 in Kijabe, Kenya, and my brothers and I were standing in the living room of our house which was attached to the tenth-grade dorm. We were ten, eleven, and twelve years old and wide-eyed.

“Yes, Dad,” was the only correct answer. He went on to explain that a three-day period of mourning had been declared across Kenya and that no one really knew what would happen next. Jomo Kenyatta was the first president of Kenya and many doubted that the transfer of power would be without violence. My father underlined that our compliance was out of respect to our community and to the nation where we were guests; we also didn’t want to give anyone with a grievance against the expat mission community a reason to accuse. Tensions were already heightened.

I’ll never forget standing in line for hours in the equatorial sun outside of Nairobi to pay respects to Kenya’s courageous leader who had stood up to Britain for the sake of freedom and independence. It was the first time I’d seen a human body without life.

“MOVE to the OTHER SIDE of the CAR!” My heart was pounding in confusion as my Teen Mission teammates and I were yelled at by soldiers with red, angry faces and rifles.

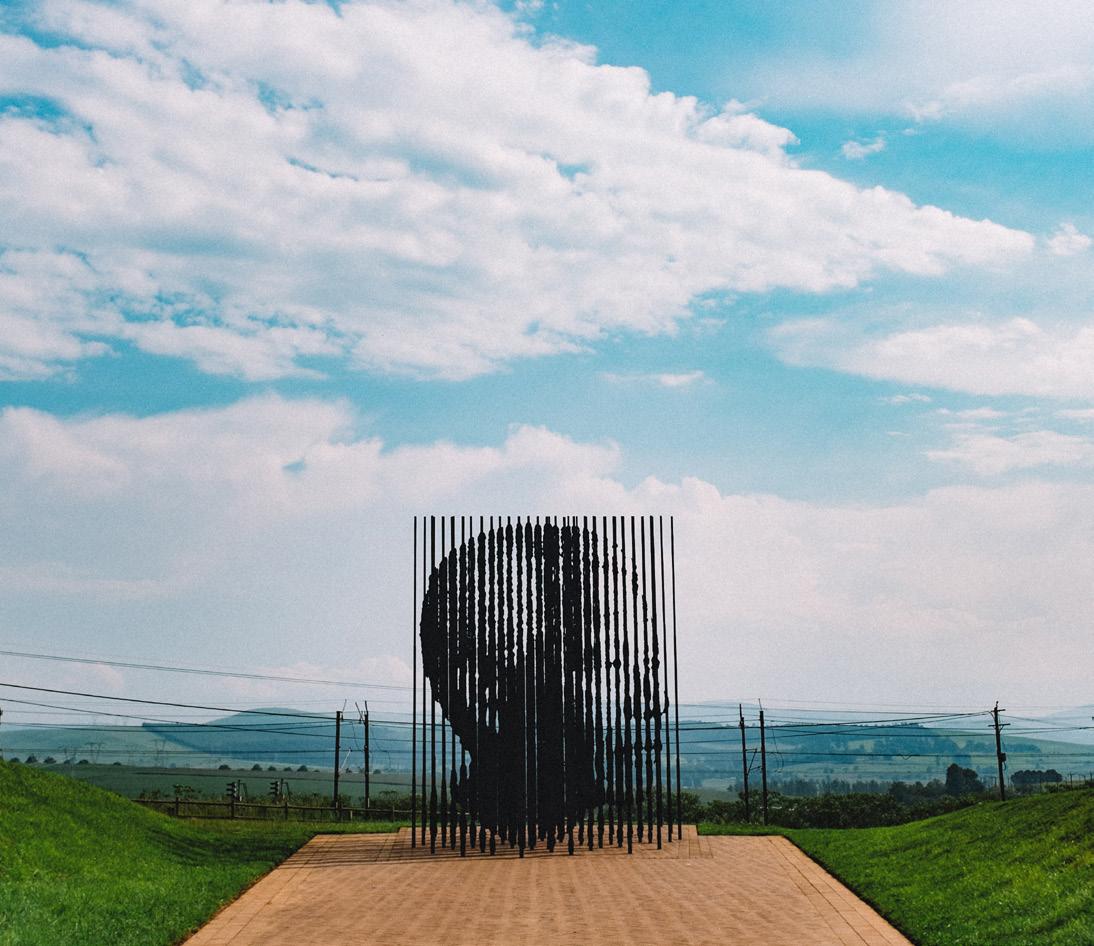

It was the summer of 1982 in Johannesburg, South Africa. My team of thirty-six Americans jumped a train for Durban where a truck would take us on to Port Shepstone. Our destination was a camp where we would do construction and programming for a group that—we would later learn—was working to break down the walls of the racial divide within the system of apartheid.

We had inadvertently made the mistake of rushing pell-mell onto a train car that was marked “Non-Whites.” (We often don’t see the things we don’t expect to see—even when we have been “prepared” to see them.) As we were herded to one side of the car, the non-white passengers were forced to the other and the soldiers created a wall with their bodies and weapons between us.

Perhaps the white soldiers thought we were doing this on purpose, as protest movements were growing and the country was tense after several bombings earlier that summer. Later, as we debriefed the experience, I felt unease at the “heroic” tone some of our leaders gave to the event; as if we had struck a blow against the “evil empire”—and as if lynching, segregation, and Jim Crow laws were not a part of our own recent past. All I knew for sure as a fourteen-year-old TCK was a sickening feeling that we had caused the other passengers distress and maybe put them in danger with our carelessness.

Throughout that summer news reached us from other parts of South Africa of shootings, bombs, and attacks of various kinds. I remember a “rest day” from physical labor at the beach preceded by numerous warnings and accompanied by hawk-eyed vigilance from our leaders. We returned to camp, and work, with a sense of relief.

Considering the stress of South Africa’s sociopolitical situation, I was deeply grateful that at the end of the summer we would pass through Kenya and visit Rift Valley Academy. I was relieved and looked forward to introducing my teammates to a country I love—where “Harambe!” (pull together) was the motto and where people lived in peace with each other.

“Welcome to Flight 543 from Johannesburg to Nairobi! We have confirmed that we will land at Jomo Kenyatta International airport where we will refuel, without deplaning, by orders of the government.”

That Sunday, August 1, 1982, a group of Kenyan Air Force officers instigated a coup attempt. The country was on lockdown. My sense of Kenya as an “island of calm” in the midst of other, more turbulent continental stories was crushed. Worse, my friends planned to meet us at the airport and I had no way of contacting them. On the runway, I stared out the window at the tarmac dotted with military vehicles, so that my seatmates wouldn’t see my tears. I would learn later that Scott Gration, an adult missionary kid (MK) who grew up in East Africa and was then an Air Force captain training Kenyan pilots, saved lives and kept innocent pilots out of trouble that day.

Our team flew on to Israel to debrief our summer experience, landing at Tel Aviv’s Ben Gurion International airport, which seemed jam-packed with soldiers in mirror shades and carrying Uzis. Being in Jerusalem felt like watching a little kid play with matches next to an open gas tank. The following month forces seeking the PLO committed the Sabra and Shatila massacre. It was tense for a reason.

In each of these snapshots, I was exposed to the realities of social and political upheaval, aware that there were many tensions and issues under the surface, aware that something powerful could erupt and situations might become violent. My elders lessened the impact of these “little t” traumas through the examples they set and through debriefing, even if done imperfectly. I was fortunate in that regard.

When the images from Washington, DC, began to flow across our screens on January 6th of this year, these snapshot memories from my mobile childhood bubbled to the surface. When I heard people asking, “How could this happen here?” I may have wondered, briefly, why it hasn’t happened sooner. The world is full of powerful, violent, and armed people who desire more power, more subjugation of others to their will, and for their own glory. The myth of American Exceptionalism is just that—a myth.

Far from making me cynical or fearful, the experiences of the past give me hope. I remember Kenyans mourning and moving ahead. I see in my mind the South Africans who risked retribution by reaching across racial and social lines. I remember Kenyan leadership dealing with a coup attempt with justice and mercy. I remember the not-unkind smiles of Israeli soldiers who teased me that my duffle bag was as big as I was. And most recently, on January 6th, I witnessed brave police officers stand in harm’s way to protect the US Congress and Constitution.

My experience has taught me that those who love others with open hearts and humility— who serve others with gracious care, who protect others with sacrificial courage, who give honor and glory to a something bigger than themselves—are the ones everywhere who keep their families, communities, tribes, and nations from sliding toward the abyss of chaos.

My hope for us, the tribe of TCKs, is that we would strive to be those people.