10 minute read

Bullet Holes Lois Bushong

Bullet Holes

Advertisement

By Lois Bushong

The small apartment above the church, located a couple of blocks from the center of the city of Tegucigalpa, was dark. The old, unpainted wooden shutters were tightly shut. The large front door to the church property was locked with a heavy drop bar holding it securely shut. My brothers and I were strictly instructed to play inside and not open the shutters even a crack. No one was out on our street playing soccer. We were all safely locked up in our homes.

I could tell by the sober demeanor of the adults who had joined my parents in the apartment that this was serious stuff. This was not the time for our typical sibling squabbles or pranks. Small fighter planes could be heard flying low over the city and our apartment. From time to time we heard the loud explosion of a bomb or the sharp pops of machine guns. When that happened, everyone in the room got really quiet. Sometimes the gunfire was on our street, just outside the door to the church property. Yet I don’t remember being afraid. I only recall it was a time of no nonsense. My main focus that morning was beating my younger brother in Sorry, our new board game.

The next day, when we were finally allowed to go outside, I was amazed at all the bullet holes sprayed along the outside walls of the church property. I clearly remember tracing the bullet holes with my small finger. There were deep, small holes where bullets had exploded on the wall. It was clearly evident to my five-year-old mind why Dad had been so insistent we keep the wooden shutters closed and not venture outside.

This was how many Latin American countries transitioned from one government to another during that era. Today, transitions are more peaceful. Not to say there aren’t still times when the military breaks into the presidential residence and either deports the current president or assassinates him or her. A civil war is declared and key government buildings are vandalized or destroyed. I recall at least three such civil uprisings during my elementary years in Honduras.

Frequently I am asked if I was afraid. No, I really wasn’t afraid, because my parents did not seem afraid. I knew it wasn’t the time to push any parental boundaries, but I do not recall fear in the midst of an obviously traumatic time.

After years of working and studying trauma in my training as a mental health counselor, I have thought about my own traumatic experiences growing up as a third culture kid. Some areas of trauma have taken a lot of hard work to heal, while other experiences are an exciting adventure to use as fodder for a good story.

After college I returned to work in Honduras. During that time we went through several periods of civil war and violence, yet again. Thanks to the resiliency skills I learned as a TCK and feeling protected by my Honduran friends, I was not overly afraid.

One particular incident of mob violence stands out in my memory. The local university was protesting something—I don’t recall the exact cause—that set off the rioters. They were angry at the United States’ involvement in our small country. I accidently got caught in the middle of the chaos as I was trying to make my way back to the safety of my apartment in the suburbs from the high school where I was on staff. The high school was located in the center of the city. As I hurried down the sidewalk, I suddenly realized I was between the riotous mob and my bus station. The mob was carrying weapons, burning a United States flag, and yelling as they looted stores and broke windows on their way toward the central park. As they came in my direction, I was trapped and feared for my life.

As I stopped and tried to figure out what to do, a shop owner spotted me as he was closing the metal doors to his store. He quickly waved me inside. When the mob got to our block, the owner, several customers, and I all huddled together on the floor behind the glass counters, protected by the heavily fortified metal doors to the store. Once again, I felt safe.

When all was clear, the shop owner let us out and we each hurriedly walked to our individual homes in the suburbs of the city. It took me about an hour to walk home, as I had to continually skirt the streets where mobs were protesting. It certainly was not safe to ride the city bus home as I typically did. I was more fortunate than some of my friends who were blinded from clouds of tear gas as the military restored peace to the city streets. For them it was more of a challenge to get home, as their eyes burned and their sight blurred. They talked of fearing for their lives while they blindly stumbled home. We talked about that day for weeks, comparing our different experiences with the riotous mob. Trauma hits all of us from time to time, in all shapes and colors and in all corners of the world.

As a mental health therapist, I work with many adult third culture kids. I have listened to their many stories of horrific trauma. I have listened to experiences of trauma unique to those growing up in more remote cultures or under corrupt dictatorships. I have felt pain and anger from stories of traumas due to civil wars, sexual abuse, kidnappings, rapes, natural disasters, murder, tropical disease, and armed robbery. Each trauma is unique and brings tears to my eyes as I am flooded with many emotions. I hurt with those who have had to experience these horrors.

Sadly, there are other traumas that are often well hidden beneath the surface and missed by some professional counselors. Those are the deep, soul-jarring traumas of being left in boarding school at a very young age, or the heartbreaking stories of growing up in a home where there was emotional neglect because parents were distracted by their world or profession. In other situations, children and youth were shamed and guilted for showing natural feelings such as grief due to transitions or saying goodbye forever to a best friend. They talk about the trauma, although some do not recognize it as trauma, of leaving all that was known and moving to an unknown world. These traumas, often missed by your average mental health provider, are just as impactful as civil war.

I have worked with TCKs who were silenced by family or organizational systems, unable to talk about the painful events they experienced. This is often due to the systems’ fear of looking bad, the loss of power or job, or financial repercussions. Emotions are messy, resulting in TCKs who are highly anxious, guilt ridden, or depressed. Sadly, these TCKs become emotionally frozen at the age when the trauma took place; they are not emotionally free to mature into their true potential.

How can parents help children who experience trauma move forward in a healthy manner, thus lessening its impact on them as adults? What have I learned as I reflect on my own history with traumatic events in Central America?

1. Children reflect the mood of their parents.

If my parents had been highly anxious during those times of civil war, I believe I would have been anxious, too. Some of my peers show signs of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) today, many years later, because their parents were anxious during times of civil war. The parents were unable to manage their own emotions, resulting in their children feeling unsafe. Good resiliency skills were not modeled to them. Some have developed very unhealthy coping skills such as addictions, lack of boundaries, denial, personality disorders, becoming people pleasers, or struggling with anger management, etc., in order to deal with the perpetual anxiety they experience, even during non-traumatic events. It is like they can’t turn off the “trauma” switch in their brain. Everything becomes a traumatic experience, where they are constantly hyper alert, stuck in the original traumatic event.

2. After the trauma has taken place, let children talk, feel, draw, or play out their emotions.

Recognize this as normal and healthy. This is how children walk through their many normal emotions to healthy functioning on the other side of a traumatic event. My brothers and I often played “guerilla warfare” with fireworks, sling shots, or BB guns as we crawled through our brush forts or bombed our small metal Matchbox cars off the small dirt roads in our crudely constructed towns we carved in the dirt. We always won in our reenactment of guerrilla warfare!

When I work with TCKs who are now adults and stuck emotionally, I have to use additional techniques such as intense therapy, EMDR (eye movement desensitization reprocessing), or long-term therapy. If they don’t go back and deal with the trauma, they often fall into one of the following defense-coping skills: Fight (anger, controlling, bullying, critical); Flight (denial, workaholic, perfectionist, anxious); Freeze (shut down, depression, detached, can’t make decisions); or Fawn (people pleaser, no boundaries, can’t stand up for themself, conflict avoider).

Today when I watch the news of riots or mob violence taking place in my own passport country, I have to take care of myself so I don’t develop a harmful coping style. My number-one way of coping with all of the craziness is to limit the amount of time I watch the news. I have to remember I am safe. This is called “grounding.” Daily, I go outside into the world of fresh air and take a walk in nature so I can clear my head and breathe in fresh air and listen to the sounds of nature. Whenever I sense my anxiety starting to climb, I focus on my deep-breathing skills, maintaining my normal sleep schedule, and eating healthy foods. And most of all, I either journal my feelings or talk to an understanding compassionate, friend who is not over the top with their own anxieties.

As I watched the news of rioters on January 6th descending on the United States Capitol building, I could not help but reflect on the various civil wars I went through in Honduras and the many bullet holes on the side of our property walls. The news that afternoon was a real trigger for me. I was a little girl once again, putting my finger into the holes left by the bullets. Yet I know I am okay here in my small midwestern town.

What trauma(s) do you trace with the fingers of your memory? After you remember, are you okay? Never forget that tomorrow you can once again pick up the soccer ball from its spot near the front door and safely play on the street in front of your home.

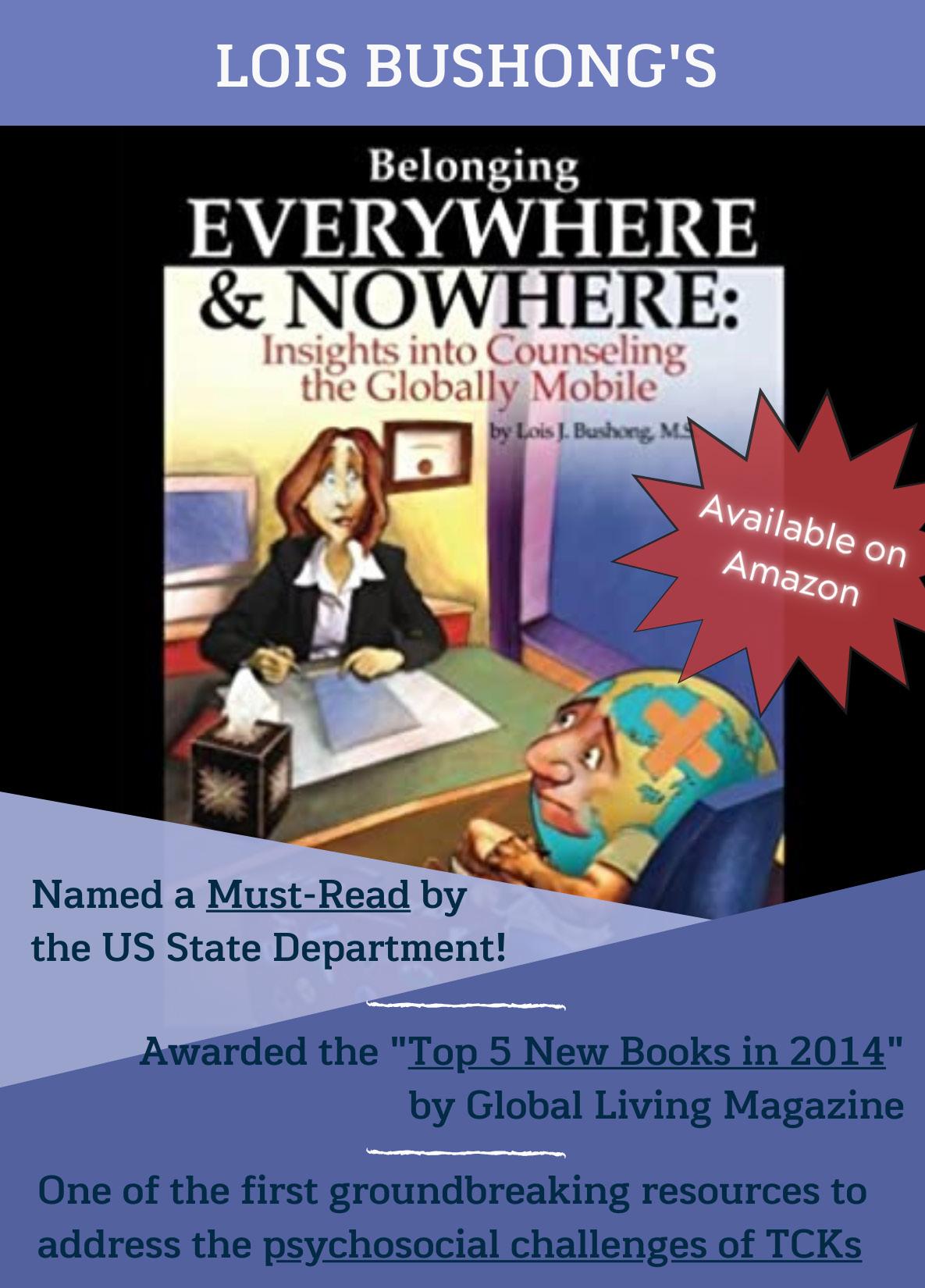

Lois Bushong is a third culture kid who grew up in Latin America. She is the author of the book Belonging Everywhere & Nowhere: Insights into Counseling the Globally Mobile. She is available for speaking and writing engagements on TCKs, expatriates and navigating transitions. Recently Lois retired as a licensed marriage and family therapist and is now working on a limited basis in her own practice in Indiana. Her clients have been internationals, TCKs, and families in the midst of transition. Website: www.LoisBushong.com. Find her by name on LinkedIn and Instagram.