AMONG WORLDS

You Are Not Alone: The Power of Shared Experiences

Tanya Crossman

Finding a Way Home N. Bhyat

Risky Relationships… Casey Bales

Safety Never Promised Marilyn Gardner

Risk-taking in the Wilderness Michael Pollock

Spotlight Interview: Ryu Spaeth

Risks in the Shallows Rachel E. Hicks

Confessions from My Comfort Zone Haddie Grace

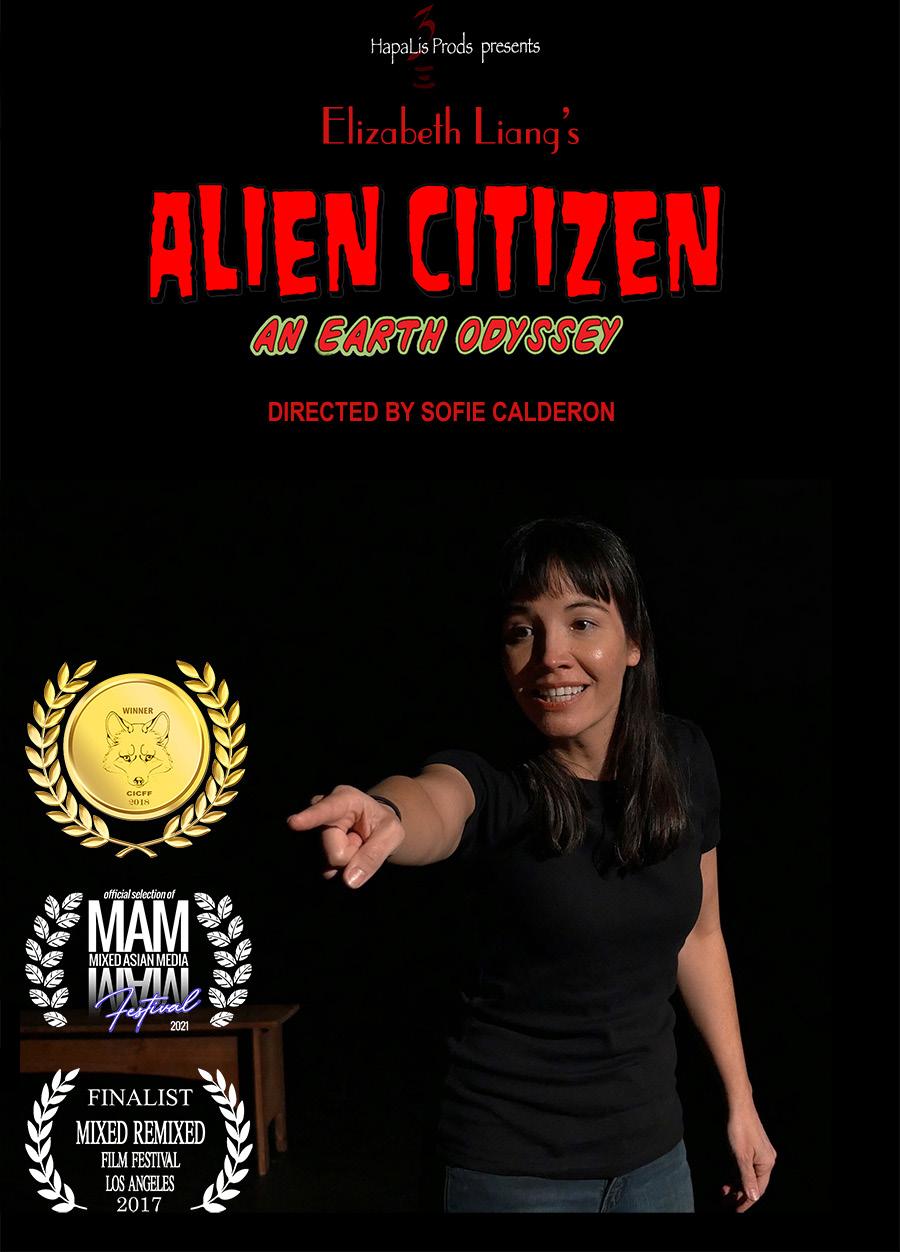

Review of Alien Citizen Danau Tanu

Cultural Chameleons

Zoe Krueger Weisel

Just Me

Beth Anne Wray

Operational Risk

Zike Pollock

December 2022 • Vol. 22 • No. 4

Cover Photo by Sylvain Mauroux (Unsplash)

Editor: Rachel Hicks

Copy Editor: Pat Adams

Graphic Designer: Kelly Pickering

Digital Publishing: Bret Taylor

You could say my life started out risky. A couple of days after I was born, I rode home from the hospital cradled in my mom’s arms—on the back of my dad’s motorcycle. (And I’ve loved being on two wheels ever since.)

A litany of memories runs through my head as I think about the risks of my TCK upbringing:

• the threat of leopards in the Himalayan foothills of my early childhood;

• daring friends over the rail at an alligator pit in the Sindh desert outside Karachi;

• bribing hotel guards in Kinshasa to let a group of us have a picnic in a penthouse undergoing renovation (we may or may not have brought spray paint with us);

• sheltering inside from violence & looting in Kinshasa, followed by an evacuation;

• riding public transportation alone as a preteen/teen in unfamiliar cities;

• and I could keep going…

“

…And when I keep going, I find myself thinking about risks I’ve allowed in the lives of my own TCK kids:

• driving my electric scooter with my three- and five-year-old wedged in behind me;

• camping and hiking on an island in the Borneo rainforest with young children (and green vipers, and beer-stealing monkeys, and saltwater crocodiles, and who knows what else);

• hiking straight up a slippery mountain in the rain for my kids’ first backpacking trip;

• living in earthquake-prone Sichuan province, China;

• and my mother-in-law probably remembers us telling her more such escapades…

Yet against all this evidence, I don’t consider myself to be someone who is comfortable with

So, will you take this risk with us and join us at our new home?”

risk. Do some situations just seem “normal” to me because of how I grew up, and so I downplay the risk? It’s hard to say. What is “normal,” anyway, especially for TCKs? One thing I do know, though, is that sometimes risk turns into fun, especially when we look back on those memories!

Among Worlds is on Instagram!

Follow us at amongworlds.

The mission of Among Worlds is to encourage adult TCKs and other global nomads by addressing real needs through relevant issues, topics, and resources.

So, in the spirit of risk and fun, I’m excited to share with you all that Among Worlds, the original and longest-running publication for third culture kids and global nomads, is transitioning from a quarterly magazine to our new website home!

Why, you ask? We want to continue to be responsive to the needs of our TCK community. When AW relaunched in 2019 from print to a digital format, we did so to meet the needs of highly mobile and international TCKs, who are scattered all around the globe. While the magazine and AW’s Instagram account (amongworlds) have enjoyed a growing audience, we realize that having much of our content behind a paywall discourages engagement, especially from young adult TCKs (ATCKs).

Among Worlds goes directly to the heart issues many adult third culture kids face: relationships, grief, transitions, home, values, and many more. AW fills a real need by addressing issues that are relevant to ATCKs today, and it “reunites” them with others of similar experience. AW also helps parents, educators, and others to better understand the needs and experiences of the TCKs whose lives they touch daily. Moving our content to a paywall-free website will enable us

to interact more with our TCK community and will hopefully foster connections among TCKs. In addition, we are excited to be able to upload all the content from our digital issues to our new blog, making articles easily searchable according to topic.

What about your upcoming issues? Our December 2022 and March 2023 issues will still be available in our beautiful digital magazine format—for FREE—but the content from these two issues will also be simultaneously added to our new online home, amongworlds.com. Our March 2023 issue will be our last digital magazine issue, published on Issuu—all future content will only be in our searchable blog format.

So, will you take this risk with us and join us at our new home? Check us out at amongworlds.com!

You can also always reach out to us via email at amongworlds@interactionintl.org. We’d love to hear from you!

Journeying with you,

RachelAMONG WORLDS ©2022 (ISSN# 1538-75180) IS PUBLISHED QUARTERLY BY INTERACTION INTERNATIONAL, P. O. BOX 863 WHEATON, IL 60187 USA. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED WITHOUT THE PRIOR PERMISSION FROM THE PUBLISHER. WE LOVE WORKING WITH INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS AND NGOS AND WILL NEGOTIATE A RATE THAT WORKS WITHIN YOUR BUDGET. CONTACT US AT AMONGWORLDS@ INTERACTIONINTL.ORG OR CALL +1-630-653-8780. THE VIEWS EXPRESSED IN AMONG WORLDS DO NOT NECESSARILY REFLECT THE VIEW OF AMONG WORLDS OR INTERACTION INTERNATIONAL.

By Tanya Crossman

By Tanya Crossman

Growing up in a business family, attending six schools as we moved four times through three cities on two continents, I didn’t know there was such a thing as a “third culture kid.” I felt the stress of acculturation, re-entry, and the grief of lost relationships without having words for these experiences. I assumed I just didn’t fit in, couldn’t cope with life as well as others did.

I learned the term TCK when I was twenty-three, volunteering with a youth group in China. Two years later I realised this term applied to me, too—this vocabulary explained my struggles. It was a relief to learn I wasn’t just a person who “couldn’t cope,” but that mine were common, understandable reactions shared by many others who experience childhood mobility.

In my thirties I became a researcher, collecting the stories and experiences of TCKs from around the world, sharing their perspectives and giving voice to their thoughts.1 Now, at forty, I am delving even deeper into TCK experiences that have not been brought to light before. Together with my colleagues at TCK Training, I am researching the risks of TCK life.

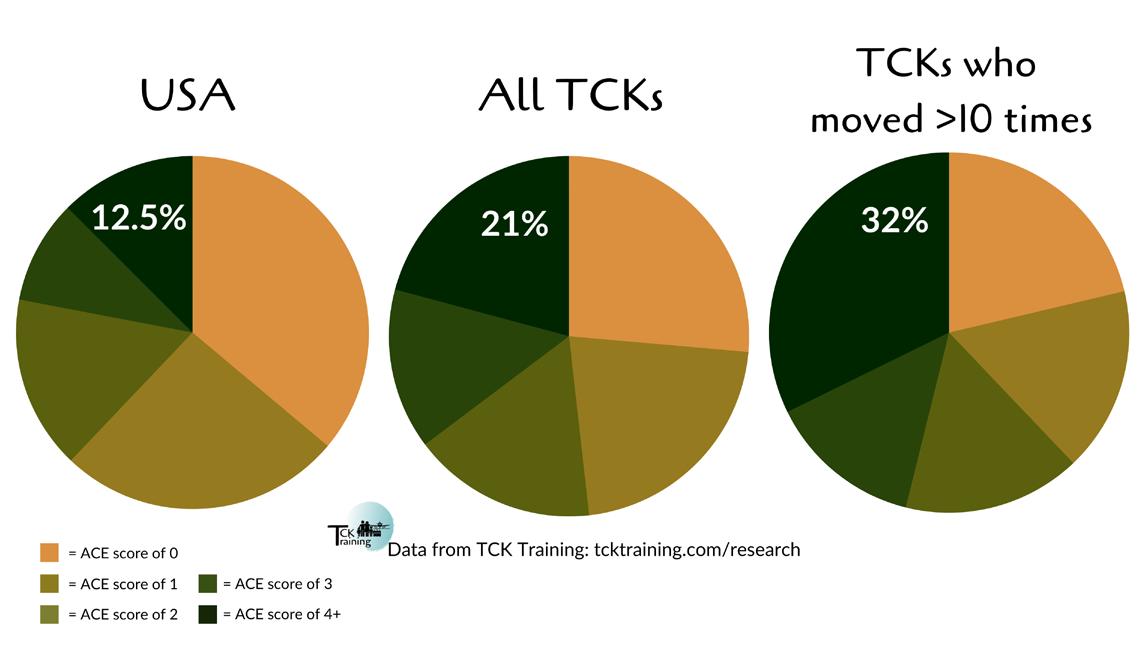

outcomes increases, often dramatically. In a survey of 17,000 Americans, 12.5 percent were at risk. Twenty-one percent of the 1,904 TCKs we surveyed were at the same risk—significantly higher than the rate of Americans.2 One in five TCKs had so many Adverse Childhood Experiences they were considered at high risk of negative outcomes in adulthood. One in three TCKs who experienced extreme mobility were at the same high risk, suggesting that mobility is in itself a risk factor.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are a way of understanding the risks of certain childhood experiences and have been researched for decades. When more than three of ten specific experiences are present, the risk of negative physical, psychological, and behavioral health

There are many reasons we may convince ourselves to downplay the risks of our globally mobile childhoods. Many adult TCKs I’ve interviewed over the past ten years have shared with me the fear of failure they developed: the pressure they feel to live up to high expectations. Some even recognised their pain but did not share it for fear of upsetting their loving parents.

Discussing the difficulties we experienced with people who were part of our support network— our parents, caregivers, and friends—can feel very risky. Childhood risks are in the past—why pile additional relational risk on top by addressing past fears now? Engaging with the deeper emotions swirling beneath the shiny exterior often feels like a no-win situation.

Where prevention and protection were absent, or inadequate, we need restorative care.”

There are so many great things that come with international life, but if we fail to discuss the potential risks, we aren’t telling the whole story. “High risk, high reward” still involves high risk. And when there is high risk, there should be high levels of protection and preventive care. Where prevention and protection were absent, or inadequate, we need restorative care.

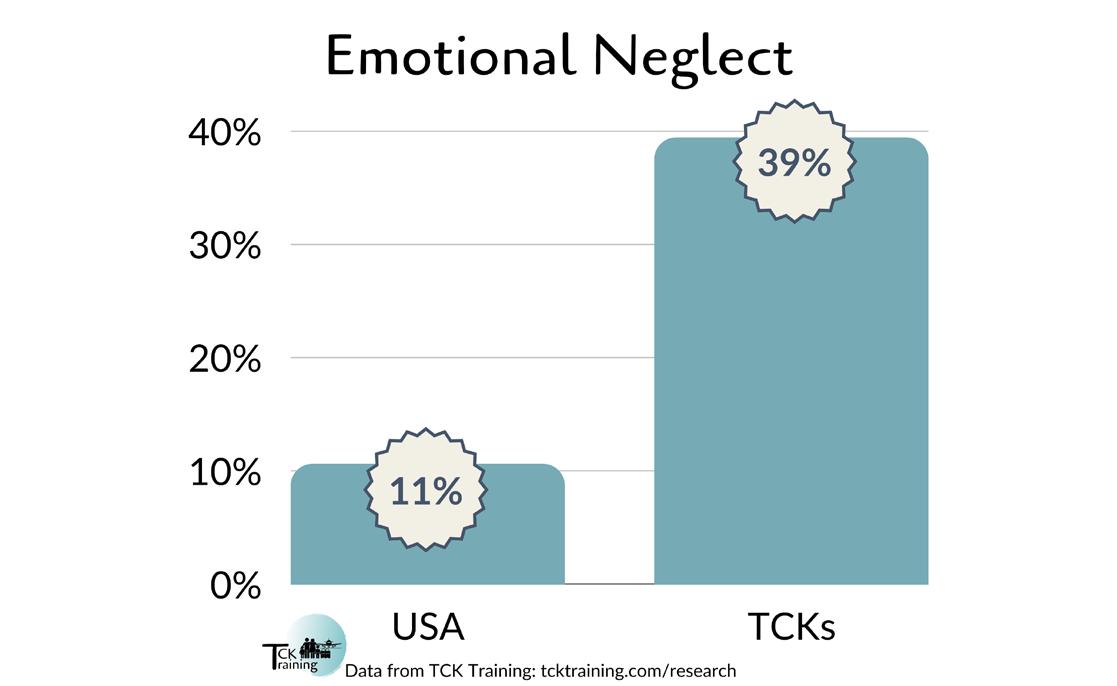

Here is one example from our research. Two out of every five TCKs we surveyed indicated they were emotionally neglected as children.3 We didn’t ask if they were neglected. We asked if as children they felt they were not loved, not special, not important, or that their family was not close and supportive. If you felt that way as a child, you are not alone. Thirty-nine percent of adult TCKs felt the same way as children. Lacking this emotional safety as a child is called emotional neglect, because the deep need we all have for emotional safety was not met.

If you had twenty TCK friends growing up, this research suggests that eight of them were emotionally neglected—that their need for emotional safety was not met. Maybe you were one of them. That’s a lot of kids in one group. It means that many TCKs may have considered a lack of emotional safety at home normal. “Maybe some people have that, but we shouldn’t expect it.” Maybe we don’t recognise emotional safety when we see it in another home because it’s a foreign concept to us.

If emotional safety is a foreign concept, if we can’t recognise it from our childhoods, how might that affect our romantic relationships as adults? How do we recognise an emotionally safe relationship when dating? How do we know we deserve to be emotionally safe in a relationship if we don’t see emotional safety as normal?

How might it affect our parenting? Even if we understand and want to provide emotional safety to our own kids, learning to do something that wasn’t modelled well in our homes or communities can be difficult.

This is what happens when we tease out the implications of just one of the Adverse Childhood Experience findings from our research.

Recognising the difficulties of TCK life doesn’t mean we throw out everything. I can acknowledge difficult things, uncomfortable things, and terrible, horrible, no good, very bad things—without letting go of beautiful things, joyful things, and wondrous things. I can live what Lauren Wells describes as “the ampersand life” by embracing the reality of both.4

What I really want you to know is this: you are not alone. Your struggles, then and now, are not because something is wrong with you. Many people have been through what you have been through—even if you haven’t heard those stories yet. The idea of Adverse Childhood Experiences and how they are interrelated with the third culture kid experience may be brand new to you—you are not alone there, either!

Many TCKs may have considered a lack of emotional safety at home normal.”

I was twenty-five when I realised that the term “third culture kid” applied to me. I was thirtyfour and the author of a TCK book when I truly internalised that I was a TCK—mostly because Ruth van Reken herself told me to own it, and it’s hard to argue with Aunty Ruth! (She is the coauthor of Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, Third Edition.)

Maybe you, unlike me, grew up with the term “TCK.” But when did you realise that there were risks associated with TCK life? When were you able to apply those risks to your own experience? When were you able to internalise that knowledge? Maybe it hasn’t happened yet. Maybe it is happening today.

If so let me be your big sister or your Aunty Tanya. Let me say to you: you can take this on board and claim it as your experience. You don’t need anyone else to justify it for you. You know the difficulties you have faced, and you deserve comfort and compassion as you process them. There are those of us who have been there, who understand, and who will stand with you.

You are not alone.

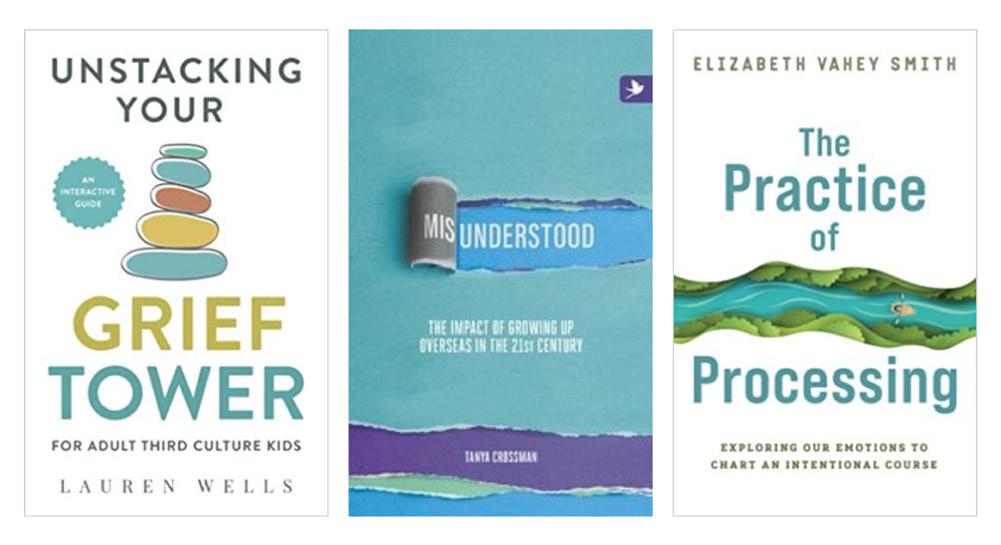

And you don’t have to go through it alone. TCK Training has built a foundation of research showing that others have shared your experiences.5 We have developed tools for adult TCKs to process these experiences.6 I particularly recommend Lauren’s short book, Unstacking Your Grief Tower.

Acknowledging the risks we were exposed to and the difficulties we experienced during childhood can be painful. Integrating the wonderful parts of our international lives with the hard parts—especially when it was all a result of decisions outside our control—can be difficult. Processing brings peace, however, and none of us journey alone.

1Caution and Hope: The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids 2022 white paper

2Crossman, Tanya. Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing Up Overseas in the 21st Century.

3Research-Based TCK Care 101

4Wells, Lauren. Unstacking Your Grief Tower: An interactive guide to processing grief as an Adult Third Culture Kid.

5TCK Training Research

6TCK Training services for adult TCKs

Tanya Crossman is the Director of Research and Education Service at TCK Training, and author of Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing Up Overseas in the 21st Century. She grew up in Australia and the US, then lived most of her adult life in China and Cambodia. Tanya began working with TCKs in 2015 and since then has become an author, researcher, and trainer focused on understanding and sharing TCK/ ATCK experiences and advocating for preventive care to improve their long-term outcomes. Learn more at https://tanyacrossman.com or https://www. tcktraining.com .

Instagram: misunderstoodtck Twitter: TanyaTck

are not alone.”

One minute I was high in the branches, the next I hit the dirt with a thump that raised red dust and walloped the air from my lungs. I looked up at the leaves as my friends shimmied down fast enough to leave skin on the bark.

“I’m going to tell your mother!” one yelled, staring down at my blank face, while the other melted indoors, certain we’d be in trouble.

Alone, after a few minutes, my breath steadied. Deciding I was only half-dead and not impaled by sharp sticks, I struggled up and stumbled home amid air sweet with the scent of burning grass. My ribs hurt and it was a very long walk.

This wasn’t my first accident running, climbing, or cycling, nor was it the last long walk home. A running fall led to a knee injury, a tour of the Dutch emergency medical system, and the near cancellation of my breakout role as a shepherdess in the class nativity play. A bike crash led to metal jabbing into my palm and a tetanus shot. Activities where things might go colorfully sideways were, it seemed, my specialty.

With age, I began to understand that mental or emotional risks could be involuntary and more impactful than gravity. Returning to my

passport country, Canada, for example, was far more intimidating than climbing the thin waving branches of a monkey puzzle. The school year didn’t sync up with my old year, and in the middle of the semester when I arrived, the rules of baseball, music notation, and French grammar all eluded me.

“J’ai regardé, tu as regardé, il a regardé. Mais faites attention! Je suis allé, tu es allé, il est allé, nous sommes allés!”

Conjugating irregular verbs proved harder and more tedious than gaining language by rough immersion and hearing the syllables clang against your ear. More complex still were the invisible social rules of my school, which didn’t follow any rules that I knew. How was I supposed to know what brands were hot, what music was cool, and what paper-bag lunches were either acceptable or gross?

On afternoons when I left our red brick school, kicking at piles of red, orange, and yellow leaves under trees that grew sparse and spindly, so unlike the tropics, my backpack pressed heavily onto my shoulders and the walk home felt longer than the day I fell from the tree. There were no friends to run for help here: I needed to make new friends who didn’t mind hanging with a weird new kid who didn’t know anything a local was supposed to know.

Splashing down onto home turf felt uncomfortable, too, in ways I didn’t expect. It took concentrated effort to uncramp my writing that jammed pages of foolscap in a thicket of narrow, illegible sticks.

I’d spent years in a place where paper was in short supply and wasting it drew the teachers’ wrath: “This is not the place to indulge your loops and whorls! That is for the fairground!”

By contrast, paper forests in my passport country rolled to the horizon and my classmates’ pens skimmed the page as loose and lazy as dragonflies.

Moving home turned out to be an extended lesson in learning, unlearning, sorting through much of what I’d learned overseas, and stowing it away in mental boxes high on a disused shelf.

I developed a new skill to navigate the natural hazards lurking in the social hierarchy of my school. Falling from a tree hurt, but tumbling from the heights of complex social structures could injure worse. Like many TCKs, I understood to avoid mentioning my years abroad or risk being tagged as weird, strange, or suspiciously foreign and best kept at arm’s length. In some instances, it could prompt my classmates to recoil like a chorus of hissing mambas.

“OMG! You lived in one of those poverty countries!”

More than one, but I left that out. It was impossible to explain vast swaths of the world to classmates with hazy impressions of many places all squeezed together and only glimpsed in news clips of chaos and disaster.

Other natural hazards proved harder to sidestep. One year, our teacher asked an

artistic classmate to draw logos for us to use as signatures on poems we would all write and illustrate. My classmates’ logos highlighted their personalities. The artistic classmate beamed as she presented mine and I smiled back.

“This one means the color black,” she said, “because that’s what I think about when I think of you.”

My classmate and I had sat in the same class for over a year and toasted gooey marshmallows at a birthday sleepover where the burned sugar made me think of sweet smoke and burning grass. Our friend’s sleepover was how I knew how loud she snored. Yet in my classmate’s eyes, I was known solely by color and was supposed to feel complimented by it.

That day, the walk home smelled of damp leaves and rotting snow.

My classmate wasn’t the only adult or child to express ideas like hers, along with a universe of incorrect assumptions that went with it. TCKs are adept shapeshifters and code-switchers but there was no shifting or adapting to such narrow boxes, which held a destructive, limiting impact that seeped inside.

When I submitted my poem, the teacher wrote, “You didn’t include a logo. -2 marks. Take care to complete your work.”

I couldn’t begin to explain it to the teacher. Like falling from a tree, the risk stung but it was worth a silent protest to remain, even if only to myself, a full person in three dimensions.

My home country became more cosmopolitan over time and the world reopened at university in an international residence. Most of the students there were international or locals whose lives had crossed cultural boundaries in some way. In the icy dark, we tobogganed on plastic cafeteria trays down steep hills

and laughed and debated late at night. It was serendipitous risk-taking and one of the best decisions of my life.

After graduation, I bought a plane ticket and went to work in the lands of monkey puzzles, hoopoes, and other places. Airplane seats and rolling wheels held a deep and comfortable familiarity, down to the salty meals with foil lids. No longer a young TCK with a tiny backpack, I was a different person, and, in the time since, shifting demographics had washed some international influence over my home country. I buckled my seatbelt, pushed back into the seat, and inched onto a new branch.

I had no idea if the tree I was climbing in this new chapter had lush foliage, broad branches or smooth bark, nor how far up I could go. I did know that if I fell, many long walks in many places had taught me how to find a way home.

N. Bhyat is a TCK who lives in Canada and grew up in the Netherlands, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. She has since worked and studied in parts of Asia, Africa, and Europe and still has an interest in colorful risks and cross-pollinating connections.

From age three to age nine, I was raised in Tokyo, a city with neon-lit streets, crowded sidewalks, and towering skyscrapers. Walking through this metropolis, especially when underground, made me feel insignificant within the endless waves of people going about their daily business. Despite the mass of people, I couldn’t help but wonder in awe at the regard the Japanese had for others. When I was around eight years old, I remember Mom accidentally leaving her purse at a bus stop in the district of Sangenjaya and then returning hours later to look for it. To her relief—and surprise—the purse was still there with everything inside it. Of course, that was the early nineties and things may be different now. But this Japanese collective behavior had a strong impact on my moral upbringing as it taught me about honesty and doing one’s best not to inconvenience others.

When I left Hawaii and returned to Japan in 1997 at the age of eleven for my mother’s new teaching destination, we moved to a small farming village surrounded by rice fields. I

enrolled in a country elementary school for fifth grade. I was considered a kikokushijo (returnee child) and was expected to assimilate back into the Japanese educational system without a hiccup. It was challenging, to say the least.

Located in Niigata prefecture northwest of Tokyo, on Japan’s largest and most populated island of Honshu, Nakajo was a small, rural farming town famous for cultivating koshihikari rice. It’s now known as Tainai City. My walk to and from school was long: one hour there and one hour back. I trudged through several feet of snow, past white blanketed rice fields in winter and grassy green paddies during early summer.

As a family, we were an enigma in Japan. My step-father, Wade, looked like a Japanese national yet could not speak the language. I looked like a foreigner, but I could speak Japanese like a native. Often, in a restaurant, a waiter or waitress would approach Wade only to end up speaking with me. A Japanese man who owned a local restaurant once raised his voice

at Wade when Wade stayed quiet as I spoke for him. I guess the man felt shunned by Wade’s silence. Or maybe he’d just never come across a Japanese-looking man being spoken for by a fluent young (foreigner) child.

It was great to be back in Japan, but it was still difficult fitting in with the local kids. They were country boys; I was a gaijin city kid—and I had just come from America. Having small scuffles during recess and cleaning time was common. I grew accustomed to not only verbal but physical abuse as well. After school, boys would throw snowballs spiked with rocks at me and shout, “Go back to America!” Wade understood the challenge I was going through and advised me on handling difficult situations, like when a group of boys tried to ambush me on a quiet backroad. He volunteered to meet me after school and accompany me home on foot or bicycle whenever he thought I might be in trouble. In many ways, as I became Wade’s personal translator, he became like my personal Mr. Miyagi from the 1984 film The Karate Kid—Wade even caught a fly with his chopsticks once.

I moved again in 1998 for sixth grade when Mom accepted a teaching position at Kanazawa Institute of Technology, an engineering university. With a fifteenth-century castle overlooking the city and well-preserved Edo-era architecture, Kanazawa is located on the west coast of Japan’s central island of Honshu, along the Sea of Japan. I was much better at making friends here. However, I do remember it wasn’t perfect. As is typical at Japanese schools, students were required to exchange their outdoor shoes for indoor shoes upon entering the building. Each student had their individual shoebox where they would store their footwear. Twice at the end of the school day, I was met with piercing pain when I placed my foot into a shoe filled with thumbtacks. I asked my male friends, and they suspected it might have been some of the girls who didn’t think so well of me and wanted me to quit going to the school. Lucky for me, I bonded with my sixth-grade teacher and became

obsessed with playing sports, especially soccer. I developed close friendships with several of my male classmates, with whom I later entered junior high school. It was in junior high school that I remember being ecstatic to win a relay event at the school’s annual undokai (sports day) for my red team. Those same good friends later traveled to Indiana to visit me.

My team and I win the tire-pulling relay race during the seventh grade sports festival, Kanazawa City Takanawadai Middle School.

I felt comfortable at Takaodai Junior High School in Kanazawa wearing the required gakuran, a uniform modeled on the uniforms of the European navy. It consisted of long black pants and a jacket with a standing collar. The jacket fastened from top to bottom with golden buttons embossed with the school emblem. Wearing this uniform was a sign of earned maturity and educational promotion all over Japan. It was at this time that I became obsessed with drawing intricate mazes, which probably reflected the path of my life up to that point. I spent hours alone in my room creating passageways that connected, blocked, surprised, and led to various adventures.

During my seventh-grade year at Takanawadai Junior High School, I was elected class president.

There were two factors that led up to this moment. First was when a couple of students and I were called to the front of the class to write kanji (Chinese characters) with the correct stroke order. I was the only one to write them in the correct order even though I was not Japanese. That impressed the teacher and my classmates. Second, it was probably my newfound popularity and blond hair. As young teenagers, we rebelled by doing things naughty young boys typically do, like smoking cigarettes or buying an adult magazine. I knew we were breaking cultural rules of conduct, but risks are only scary when you don’t have friends taking them along with you.

Living in Kanazawa was a time I really felt at home. When asked my nationality back then, I often said I was Japanese, not American. The evening before our flight back home to Indiana from Kanazawa in 2000, I asked Mom to drive me to my junior high school for one last time. The building was dark and empty. It was late at night.

I sat silently in the car, staring at the campus, with only the schoolyard spotlights illuminating the dark buildings. Sadness fell upon me like a coastal fog. These walls housed some of my fondest memories yet; I needed this last goodbye.

The long flight to Indiana the next day felt like heading for outer space. I was flying to a complete unknown. I’d formed a lasting bond, not only with my friends but with Japan and a culture that had become second nature. When people cross borders and get to know one another, it closes the door to hatred forever. I had finally adjusted to my second culture, and I didn’t want to leave.

Casey Bales lives his destiny as a bridge between America and Japan. He spent ten of his formative years being schooled in the Japanese educational system in Japan and later continued his Japanese education in the United States—thereby completing his entire K-12 education as the only non-Japanese in each grade level. Having grown up as a third culture kid (TCK), Casey is continuing his adult cultural journey in Tokyo, Japan, with his wife, Yuki.

*This piece is an excerpt from Casey’s memoir, Invisible Outsider: From battling bullies to building bridges, my life as a Third Culture Kid (Summertime Publishing, 2022).

https://www.caseybales.com/ https://www.instagram.com/mixedoutsiders/

The first conversation in the United States about safety that I remember came after 9/11. Suddenly “the enemy” had come to our soil and we were no longer safe. Money, big houses, security systems, fat retirement accounts, and good jobs were not enough. Most of those killed on 9/11 had those and more, but it did not save them.

The solution was war. No matter what lawmakers and politicians say now, the consensus made by the powerful of the land in the United States was that war was warranted, war was justified. And so, we went to war.

But it did not make us safer, and it did not take away our fear. “The enemy” moved closer. The enemy was now at our borders. Those who would take our jobs and bring in drugs must be stopped. Those who would bring their ideology to disrupt our “way of life” had to be kept out. So we proposed walls and fences, bans and limited entry.

But it did not make us safer, and it did not take away our fear.

ISIS emerged, a real threat to people living in Syria, Iraq, and Turkey, but arguably not so much to those watching the nightly news on their plush, comfortable couches. There was more fear. The world was a scary, scary place. A formation of a broad international coalition was designed to defeat the Islamic State and ISIS went undercover to emerge only randomly.

But it did not take away the fear.

As my husband and I periodically went to the Middle East to work with humanitarian aid groups on the ground, the number-one question people would ask us was, “Is it safe?” I never knew how to respond.

The number-one question people would ask us was, ‘Is it safe?’”

In the essay “The Proper Weight of Fear,” my friend Rachel Pieh Jones writes what is a fitting response to that question:

Of course we were safe. Of course we were not safe. How could we know? Nothing happens until it happens. People get shot at schools in the United States, in movie theaters, office buildings. People are diagnosed with cancer. Drunk drivers hurtle down country roads. Lightning flashes, levees break, dogs bite. Safety is a Western illusion crafted into an idol and we refused to bow.

And then came 2020. Suddenly “the enemy” was no longer over there, far away from our homes and our television screens. The enemy couldn’t be kept out through a wall or closed borders. Instead, the enemy was everywhere. It was a virus, a virus that could be anywhere at any time, floating through the air, ready to randomly attack. But it was more than a virus. The enemy was our neighbor. It was anyone who was not wearing a mask. It was the spring break revelers and COVID partiers. It was the people who did not take the virus seriously. It was the person passing us who coughed. The enemy was the person who shopped at our grocery store and chose to go the wrong direction, defying loud orange arrows. Danger was everywhere and our fear was out of control.

But even when we wore masks and did all the right things, people were still afraid. Afraid and deeply angry at those who did not do the right things.

It turned out that no one was safe. Sons and daughters, husbands and wives, uncles and aunts, random strangers—they were all potential carriers of this virus that rocked the world. We learned that no place and no one was safe. As much as we wanted to carve out our little utopias where everyone was safe, where the enemy was far away, and fear was nowhere to be found, it was not possible. Instead, everywhere we looked there was danger. It didn’t matter how big our houses were or how much we scrubbed our groceries, we were not safe. We couldn’t build walls to keep people out. We couldn’t create wars to send a message. Our own families became our enemies. We were victims of a virus much smarter than us.

So, we created vaccines. The vaccines would solve the crisis were the words from the leaders. We would all be safe. We could begin living.

Vaccines were created—but they did not take away our fear. Some chose not to get vaccinated, and they became the enemy. And then “the Omicron” came. And even if we were vaccinated, even if we were boosted, Omicron invaded our households and took hold of our news sources. An insidious enemy, you didn’t know where it was, and you didn’t know how to avoid it. Locking doors didn’t help. Cleaning didn’t help. Isolating didn’t help. Even the vaccine couldn’t keep us safe from the virus. We needed boosters. And more boosters. And still more.

The savior vaccine had failed us, and it did not take away our fear. Could it be that we have safety all wrong, that we will never be truly safe as long as we live on this earth? Could it be that safety was never promised, that the nature of being human is one

of risk, one that will ultimately lead to death on this earth for everyone?

What do we do in a dangerous world when we crave and long for safety? What do we do in a world that demands risk-taking just by existing?

We keep on going. We keep getting up, even when it’s difficult, oh so difficult, and we dread the day. We keep on loving, even when it hurts so much. We keep on taking risks, because life itself is a risk and trying to live risk-free is a terrible and impossible life to live. We keep on going from strength to strength, because really—the only truly safe option is recognizing that we are not safe.

“

If we strive to be safe, we will never, ever win. That’s the reality of life. We were never promised safety, we were never promised a life without difficulty.

My faith tradition confronts me with two realities: The first is the reality that bad things will happen. But there’s a second reality that I’ve not only seen, but I’ve experienced in times when I have felt fear rise and the desire for safety overwhelm me. And that is the reality of a God who never promised safety, but always promised his presence. As I was writing this, I remembered these words by Madeleine L’Engle, and I leave them with you as a benediction, a reminder that I was never promised a life of safety but the powerful love of a God who cares.

“If I affirm that the universe was created by a power of love, and that all creation is good, I am not proclaiming safety. Safety was never part of the promise. Creativity, yes; safety, no.” (Madeleine L’Engle, And It Was Good)

Marilyn Gardner is a public health nurse and writer who lives between worlds, but mostly in Boston. She is an adult TCK who was raised in Pakistan, and she went on to raise her children in Pakistan and in Egypt before moving to the United States. She has lived in Pakistan, Egypt, the United States, and the Kurdish Region of Iraq. Marilyn began writing in 2011 after participating in a humanitarian aid trip to Pakistan. Revisiting her childhood home and working in this relief effort awakened a long dormant desire to communicate what it was to live between worlds. Her writing and speaking come from a place of knowing what it means to live between. Marilyn is the author of Between Worlds: Essays on Culture & Belonging and a memoir, Worlds Apart: A Third Culture Kid’s Journey, and she is the editor of a recently published community cookbook project called One Cup at a Time: Recipes for Recovery. You can also find her writing in Plough Magazine, Fathom Magazine, A Life Overseas Blog, and her own blog, Communicating Across Boundaries.

Could it be that we have safety all wrong?”

What first came to mind when I was invited to the “Canadian wilderness” to help lead a Wilderness Camp for adult third culture kids this past July was the book Hatchet by Gary Paulsen.

In that story an adolescent boy is flying in a small prop plane to visit his father in Canada when the pilot has a heart attack and crash lands in a lake in a remote forest. The plane sinks, making rescue even more difficult, and the boy must survive using his wits and a hatchet, his parting gift from his mom. Cold, hunger, mosquitos, porcupines, a moose, (did I mention MOSQUITOS?), and other challenges make for a palpable, harrowing tale.

All spring I relished these thoughts: an adventure of “humans against the elements” with a group of young adult TCKs and ATCK co-leaders who “got it.” Overcoming challenges together is a great way to bond quickly, and with other ATCKs, I knew those bonds could form quickly in the right setting. Having grown up in the mountains of Vermont and in the highlands of Kenya, hiking, camping, paddling, and climbing in wild places is revitalizing to me.

We were headed into all the key elements of adventure: horseback riding, rock climbing, kayaking, and hiking in the mountains where elk, moose, and grizzly bears roamed, living in tents that had just been resurrected after a literal crushing storm. In between, we would split wood and help with cooking, and immerse ourselves in outdoor life—axe throwing and bonfires, outhouses (let’s be real) and camp cooking, fastchanging weather, and the sweetest air you could imagine. For me, that kind of life isn’t about a contest so much as it is about finding harmony with elements that can give wonderful gifts and can also kill you. Risk in its essence.

Even getting there was challenging: two flights to arrive in Calgary, an overnight in the home of a friend of a friend, then a five-hour drive up into the Blue Brona Wilderness. On July 1st, as we approached the last fifty kilometers, entering gorgeous valleys and increasingly dramatic geology, our trip leader, Ben (an ATCK himself) said, “Go ahead and text or call your family; in a few kilometers the only cell coverage will be at the top of one of these mountains.” After leaving a message for my wife and texting my kids the

connection was gone. And then it began to snow—in July. Really.

The soon-arriving ATCKs had similar stories: mud, rough roads, a broken bumper and headlight, and several other multi-hour delays that resolved themselves finally with everyone fed and warm around a fire, under cover of a high canvass roof. Ben had beautifully crafted our opening so that we established a sense of welcome, care, safety, and an invitation to transparency and vulnerability.

After a deeply chilling night, despite the small wood stoves in the ten-person tents, the day began with “cowboy coffee”—hot, strong, and black. Breakfast around the fire, music, sharing stories, affirming the story-sharers, a short encouragement, and then solitude-protected, intentional time to be alone with our thoughts, our senses, and our spirit. We encouraged each person to remember and to connect with themselves and also to that which is much bigger than ourselves: nature and the eternal Mind and Spirit.

After lunch (prepared by angelic volunteers who coordinated meals all week!), some campers split wood, some hiked a waterfall, and others took to horseback—learning to curry, saddle, and ride a diverse stable of mounts. My first day was on a sassy, black Morgan mix and she was strong, sure-footed, and fearless, even when the lead horse shied from grizzly bear scat on the trail. I felt sure that if there were a need, she and I could outrun a grizzly. Fortunately (or disappointingly?), attempting such a feat was not necessary.

Our days fell into a rhythm of solitude, community, and challenges to overcome, on the banks of a frigid mountain stream under skies that went from sunny to cloudy to rain and back in quick succession and were slathered in stars at night.

As third culture people often do, we quickly established rapport, told each other stories, shared talents in art (charcoal drawings), music (guitars, cajon, and voices), wilderness skills, and pure courage (two women immersed themselves first in the iciest stream this side of the Arctic… and liked it).

It was at this point, still early in the week, that real personal RISK raised its dreadful, wonderful

head—and it wasn’t about the grizzlies, or the rock climbing, or the fog that enveloped our hike as we approached some cliffs. Not only were “life stories” being shared, but we began to talk to each other—on hikes, around the fire, currying horses—about our lives, our hurts and traumas, our joys, sorrows, and agonies, our beliefs, and our lived experience.

Our sharing, still peppered with laughter, took deep and bumpy paths around abuse, gender and sexual attraction, confusion over local and global politics, questions of faith or the lack thereof. One on one, in small groups, or all together, we listened to each other pour out, through tears, tales that included crushing loneliness, anxiety, depression, and harmful coping strategies. Marvelously, in the next breath, there were also stories of rescue, redemption, belonging, healthy coping and healing. Somewhere between were the ongoing narratives of doubt and delight, fear and courage, searching for answers, and sometimes getting glimpses of what could be insight. We acknowledged the struggle that is life and the particular struggles encountered by people like us who grow up mobile and cross-cultural. Together, we confessed our limits and mistakes, and celebrated our gifts and victories.

In the end, the big risk was not so much facing the Canadian wilderness; the risk was in trusting each other with our stories; opening up some windows in our souls to allow others to really see us, to share empathy and curiosity and care. From my perspective, there were powerful rewards. We left with new friendships—people who could show up at our door knowing they would be welcomed, fed, sheltered, and celebrated. There was new freedom, a sense that one could be known and loved, regardless of the scars one carries. And there was relief in knowing that not one of us is alone in this crazy wilderness of life, even when we feel, metaphorically, like we are on the back of a horse we just met, in the middle of a rain-swollen river, surrounded by potential friends, getting our feet wet.

It was absolutely glorious; I can’t wait for next summer.

Michael Pollock , an adult TCK with Kenya, US, South Africa, and England a part of his developmental years, has also been an educator in the US and China. He leads Daraja, meaning “bridge” in Swahili, as a coach, advocate, and consultant for global TCK care. Michael is an author of Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds (third edition). A dad of three amazing TCKs, he believes third culture people are uniquely and powerfully poised to impact the world for good.

In this issue, we introduce to you writer, journalist, and TCK Ryu Spaeth. Ryu is an editor at New York Magazine . He was born in Hong Kong and grew up in the Philippines and India. In addition to being a TCK, Ryu is also a cross-cultural kid (CCK), as his parents are different nationalities/ ethnicities. In this conversation, Ryu describes an experience that many of us have had: first grappling with TCK identity issues upon returning to his passport country for university. In talking about the concept of home, he explains how living in a big city like New York reminds him of other big global cities he’s known. Besides New York Magazine , Ryu’s writing has also appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, and The New Republic . Enjoy getting to know Ryu Spaeth!

My father is an American from New York who moved to Tokyo in the late 1970s to work at the Yomiuri Shimbun , one of the country’s largest newspapers. He met my mother there. After they married, they moved to Hong Kong, where I was born, then the Philippines, then India, where I graduated from high school in 1999.

I think I probably was aware of the concept in high school, but it didn’t really resonate until I moved to America for college, when it became clear that I was neither an American (which was what my passport said) nor an Indian (where I had spent the bulk of my life) nor Japanese (my mother’s country). I felt very much that I was in a no man’s land between places, without a home to call my own, and that feeling stemmed from spending my formative years as a third culture kid.

Tell us a bit about your experience as a TCK.

When did you learn about the concept of being a TCK? Did it resonate with you?

What early interests guided you into your chosen career?

I’ve always been a reader, and I was always interested in literature and history, two subjects that are of great importance to journalists.

Growing up in India and traveling all over the world have been vital in giving me a perspective that a lot of American journalists don’t have. This was my true education, much more so than anything I learned in university. I think it has probably had a similar impact on my personal life, though it’s also an alienating experience that not a lot of people can relate to. I’ve always felt a bit of an outsider in that respect.

Absolutely. I feel like I am less susceptible to notions of American exceptionalism, to name one example, and I opposed the Iraq War when I was in college not because I knew anything about geopolitics really, but because of some vague, visceral sense that America was behaving arrogantly and badly. Going to an international school also instilled in me a deep respect for pluralistic diversity and a tolerance for all kinds of people, principles that are unfortunately valued less and less in India these days under [Prime Minister] Modi and the BJP [his party].

I think being able to see life from other perspectives is important. Knowledge of different cultures also just makes you a more sophisticated person, more worldly; and journalists pride themselves on knowing things, on being people on whom nothing is lost.

I felt very much that I was in a no man’s land between places.

How have you experienced your background as an asset in your career?

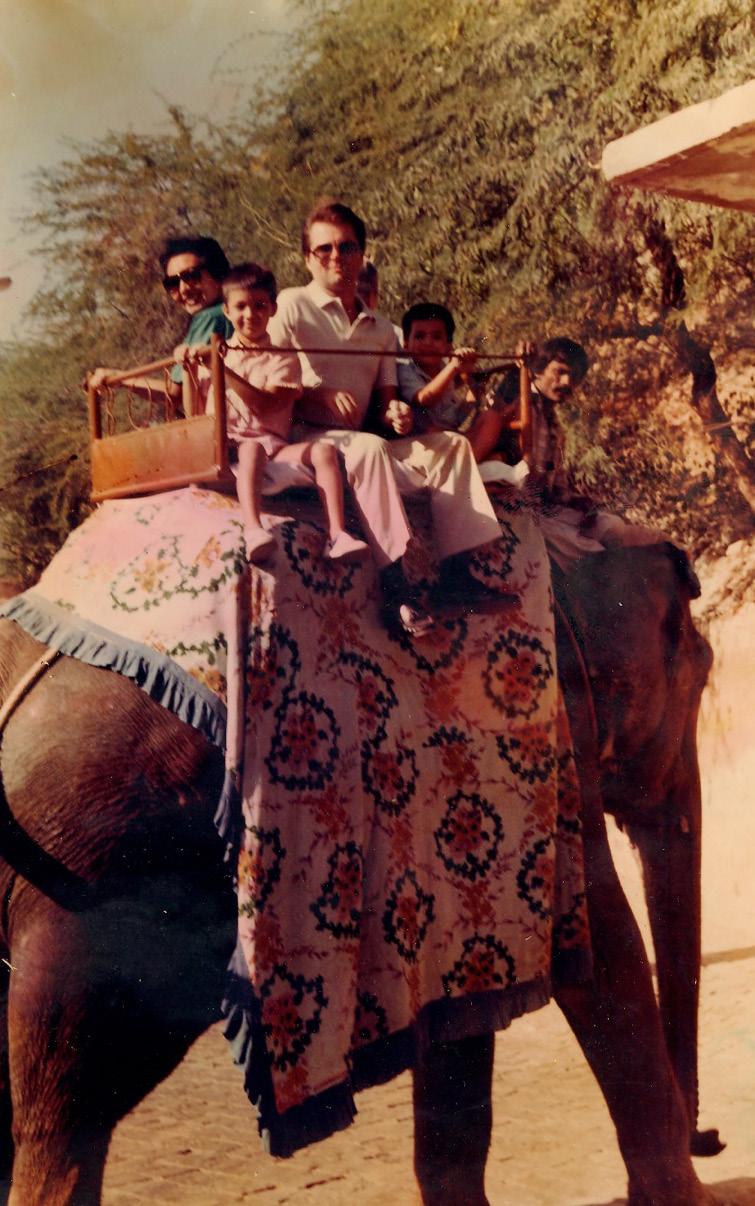

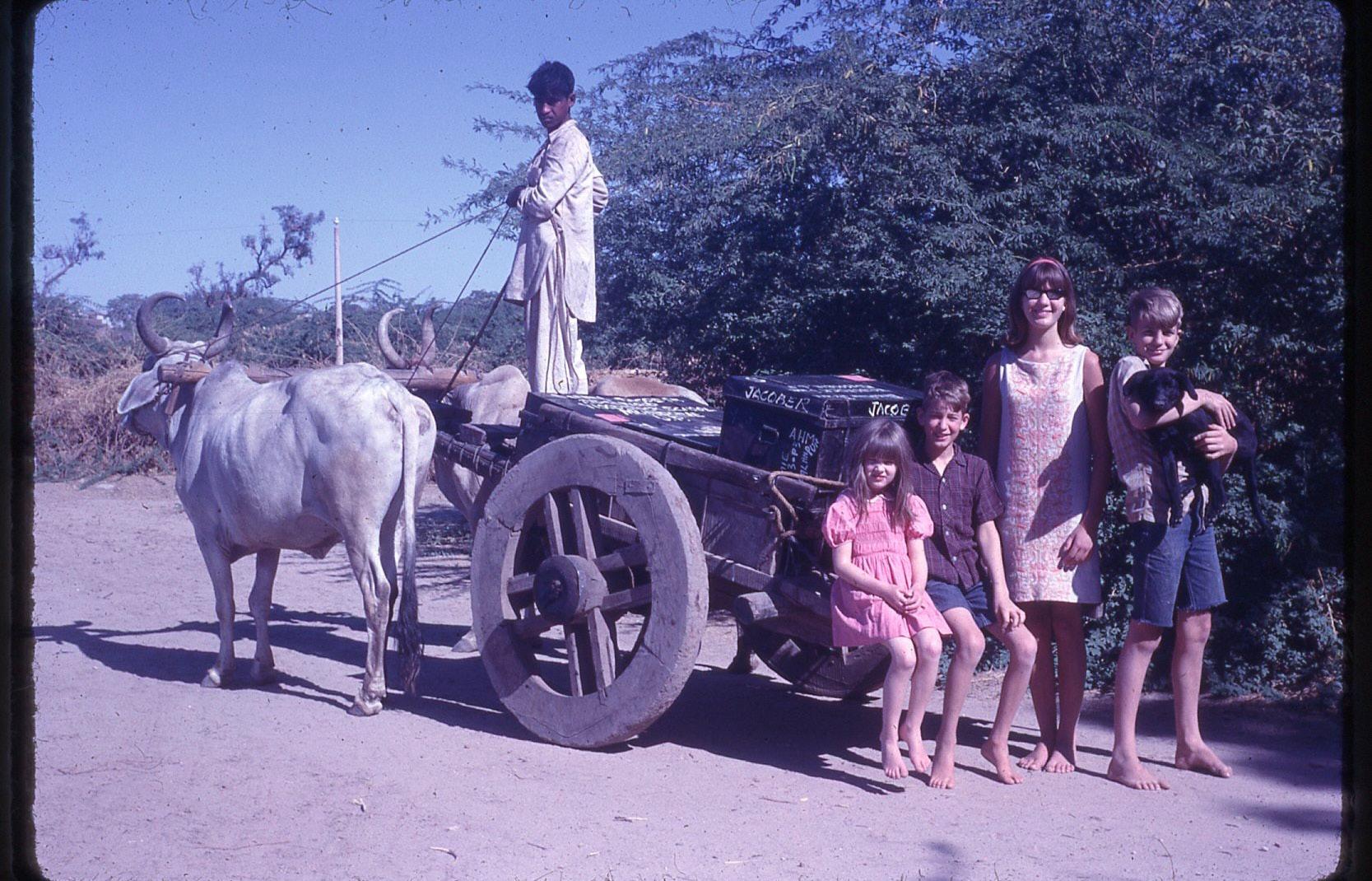

Did your childhood/teen years affect how you think politically, especially in terms of world politics?Ryu and his family in India.

There are vast swathes of American pop culture (particularly television) that are completely unfamiliar to me, which is a hindrance for anyone who wants to write about American life.

Have

I very much wanted to put down roots after college; I didn’t want to roam the earth forever looking for a home. I found that home in New York City, in no small part because it is reminiscent of the places where I grew up. The noise, the bad smells, the chaotic energy remind me of New Delhi, while Chinatown could be a simulation of Hong Kong. And you can find some of the best ramen in the world here, too.

I did not feel like an insider for a very long time, but now I suppose I am, in the sense that I occupy a senior position at an elite New York institution. New York is the only place that feels like home, with the exception of Japan, where I spent long summers in my youth and where my relatives live.

This issue’s theme is “Risk.” Tell

I suppose the greatest risk I took was becoming a writer. Journalism is a difficult profession even in the best of times, and I could so easily have failed and grown bitter. But if I’ve achieved a modicum of success there’s no guarantee it will last. So, I’ll say the jury is still out on the question of whether I’ve flopped or not—as Montaigne said, “Count no man happy until he’s dead.”

What about your background creates hindrances to your work (creative or professional)?

you struggled with or embraced the idea of “settling down” in one location? What does that look like for you?

Your writing sounds like you could be an NYC “insider”—do you feel you are? Does it feel like home to you? If not, where is home for you?

us about a time you took a big risk (and if it succeeded or flopped).

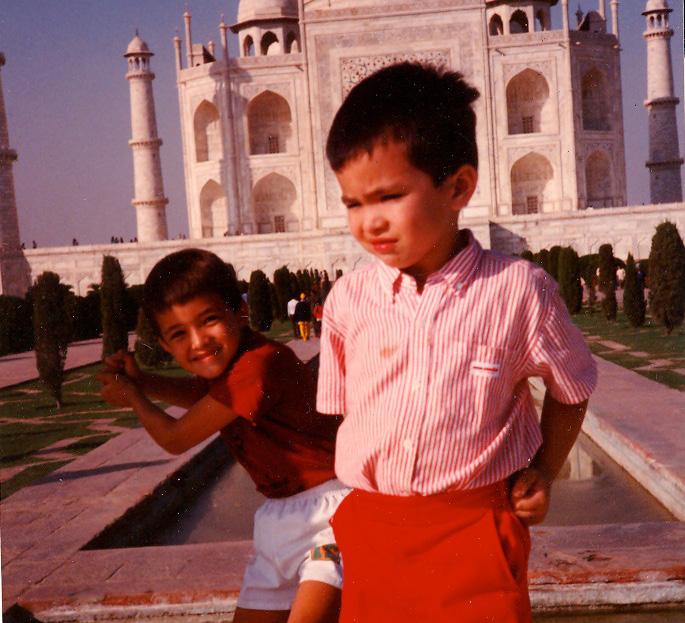

I didn’t want to roam the earth forever looking for a home.Ryu (left) and his brother at the Taj Mahal.

It was a gorgeous, slightly chilly spring evening. My husband Jim and I were taking a walk around the neighborhood with friends, a couple and their baby, whom we’d known for several years. I was quietly enjoying our conversation, enjoying their presence. Time spent with them was always heart-warming—they’re the kind of friends with whom you can laugh and goof off, but also share deeper stuff.

And suddenly, they did. “We’re thinking about moving to Georgia,” one of them said.

Immediately I could hear a huge metal gate inside me crashing shut.

My chest tightened and I took a slow, deep breath. I was thankful that Jim intuited what was happening inside me, and he bought me some time by asking follow-up questions. I managed some wows and mm-hmms and oh, okays and soon we were parting ways to head to our respective homes, where I slumped onto the couch in a predictable funk.

If you’re a TCK with a highly mobile past, you probably know exactly what happened. It’s what happens to most of us when someone we’ve been friends with or getting close to says they’re moving away: that friendship gate slams closed to protect our hearts from yet another painful parting. While we go through the motions of perhaps another long goodbye, we’ve already pulled away inside.

I didn’t want to lose this in-person friendship. I was almost mad at myself at first for letting these dear friends into my life and heart, for letting down my defenses. My impulse was to shut up my heart.

But what kind of a life does that make? Annie Dillard once said, “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives.” If I spend my days closing up my heart, I will spend my life with a closed heart. Of course.

A life of high mobility can make us shallow— relationally and in terms of knowledge and understanding. It’s an “occupational hazard.” If we’re often moving from city to city or country to country, we may become familiar with many places, cultures, and people. We think we know them, but our knowing doesn’t go very deep. Part of this is because of the lack of time spent, and part of it is because our hearts try to protect us.

We make and then lose relationships, over and over again. We lose touch with people. Even if we do stay in contact over distance, the relationships are often more shallow and less satisfying than they were in person. When we reminisce with old friends, the memories sometimes feel paper thin.

Or we live somewhere new for a while. We learn enough of the language to get around using public transportation or to order food. We take pictures of ourselves at all the key landmarks and attractions. And we’re aware the whole time—like an undercurrent—how shallow our knowledge of that place and people really is.

Energy—emotional and mental—is required of us for really seeing others (places or people); and only when we truly see can that seeing lead to knowing and loving. How much energy do we have to spend on yet another new place or person? How do we not exhaust our energy “reserves,” or at least find a way to fill them up again when they are depleted?

And the time- and energy-suck of social media exacerbates this, even if it also—paradoxically— helps us to hang onto friendships scattered across the globe.

Staying in the shallows is risky. It feels easier, and maybe it is in some ways. But the big risk is we may arrive at our later years realizing that what we missed out on was, in fact, life. Years into adulthood, we may find that we have become shallow people. We’ve either forgotten or haven’t ever learned how to attend to people or things around us. We’re just flitting on the surface of everything.

That’s a jolting realization.

But becoming aware of the risk of shallowness doesn’t mean we know what to do about it.

I’m going to offer a few things that may help us. They are mostly all practices. So, you’re probably not going to do them unless you decide the shallows are riskier than the deeps; unless you find some courage inside you to launch out beyond where it feels safe, beyond where your feet can touch.

And, by the way, when I say practices, I refer to the word in the sense it’s often used in religious communities or ways of life: habits and orders of daily life that we choose in order to slowly shape ourselves into a different kind of person.

You already do this. You already have orders or

We may find that we have become shallow people.”

routines in your daily life, in your daily activities, that are shaping you. You just may have never examined what those practices are and how they are shaping you—what kind of person they are shaping you into. It’s good to examine those things; it’s good to ask, “Who or what is forming me?” and “Am I OK with that, or does something need to change?”

So, here we go:

I mentioned attending a moment ago. Learning attentiveness is a practice. As I said before, before we can know or love, we have to learn to see. Pay attention. Try to nurture in yourself curiosity in others—grow in listening. Begin to notice facial expressions, body language, eyes that light up in delight. Let others surprise you with their otherness. (Forget about yourself for a while as you do all this.)

Wherever you are, take in sights, smells, tastes—not in the consumerist way a tourist does, but just to delight in what you hear and see and smell. You don’t have to own this place in some way. Just be there and notice it. Learn what you can. Don’t rush through each moment.

This is somewhat revolutionary. What I mean is this: Stay. Commit.

That highly mobile life you’ve been leading? And to which you have perhaps become addicted? Maybe your life would be richer if you decided to stop moving and actually stay. Plant yourself somewhere specific. Go deep into that community—let it become a part of you. Grow a root or two. Experience what it’s like to develop a longer history with the people around you.

Learn the unique beauty of deep, rather than the thin beauty of broad. You can’t be an

expert on every place or everybody. Instead of trying to, become an expert on this place and/ or these friendships.

This applies to relationships in other ways, too. Stay in the moment of a hard conversation. Be willing to sit in that discomfort long enough to push through to a reconciliation, or at least to an understanding. Commit to that in-person relationship long enough to experience—and even learn to be grateful for—its long and varied seasons.

Last summer, I heard writer Lauren Winner drop this nugget of wisdom at a conference: voluntary confinement can lead to inner spaciousness. Let that percolate in your brain for a bit…

I’m pretty sure most of us have ADHD by now. If we weren’t predisposed to it, our tech habits have doomed us. You’ve probably read at least some of the alarming studies that show how our use of media and technology is actually rewiring our brains so we can’t pay deep attention anymore. (I mean, how many of you are still reading this essay?)

But can boredom be a practice? And even if so, why is it something we should try to cultivate? OK, maybe I don’t actually mean learn to be bored—what I mean is, don’t try to fill every single moment of your waking life with stimulation or input. When you’re in line, or on a train, or in the doctor’s office waiting room, don’t reach for your phone, or turn on the radio, or grab a magazine. Believe it or not, there’s a lot more going on in your mind than you imagine. Give your brain time to rest, to wander, to let some things surface and some things sink. Our brains need time to recharge beyond just when we sleep. Often, periods of what might look like boredom end up leading to creativity, new ideas, and surprising revelations.

My kids would always roll their eyes at me when I would say, with a wink, “Only boring people get bored.” Let your mind surprise you with all the magical and interesting things it can do if you just let it be, not seeking to prod it with external stimulation all the time. A practice of enjoying “boredom” can actually lead us to richer, fuller lives.

I’m an English major, a former English teacher, and a poet and writer, so I know I am seriously biased in prescribing this practice. I won’t go on about it but will just say briefly that reading good literature is formative, whereas reading nonfiction is informative. When you read a well-written piece of fiction, you live vicariously through others, learning to see what and how they see. This often leads to an increase in empathy, which can make us deeper and wiser. OK, that’s all.

(Quick caveat: When we are in the midst of trauma or crisis, these practices are very difficult, if not impossible. There will be time for these later, once healing comes.)

All of these practices involve a cost, usually in terms of time and energy. But inattentiveness and shallowness also cost us. The question is, which price would we rather pay? For my part, I want the practices that lead to more human flourishing, to that perhaps messier but richer, deeper life that makes living worthwhile.

Our brains need time to recharge beyond just when we sleep.”

Rachel E. Hicks is a TCK who has lived in India, Pakistan, Jordan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Hong Kong, the USA, and China. She is the editor of Among Worlds. She is also a poet and freelance copyeditor. Read more about her work at rachelehicks.com .

35 Among Worlds Haddie at Lake Louise, Alberta.

35 Among Worlds Haddie at Lake Louise, Alberta.

Ihave a confession to make. For a third culture kid, I am not particularly adventurous. I haven’t spent much time outside of the countries where I’ve lived, and I don’t really want to. I don’t like to try new things. If you want a travel buddy who will fly with you on a whim somewhere faraway to bungee jump, scuba dive, and gobble up unfamiliar street food, you will need to recruit elsewhere.

My favorite place in the world is the safe and cozy center of my comfort zone. I am not a risktaker. I stop at yellow lights. I buy mild salsa. I have never broken a bone. I paid a painful amount of money for a consulting session with a cross-border tax professional and had my taxes professionally filed in both the US and Canada because I was so concerned about unintentionally making a mistake. (When you are required to report to two revenue services, that’s when you absolutely should not take risks.) If I am feeling unusually reckless, I come home from the grocery store with actual Nutella instead of budget-friendly, generic brand chocolate hazelnut spread. And that’s about it.

When I moved to rural Cameroon for an undergraduate internship at age nineteen, people praised me for being so adventurous, so brave. The real story is that I had wanted to go back to Senegal, where I grew up, but my university faculty felt it didn’t meet my program’s international internship requirement because it wouldn’t be a new experience for me. The university offered options for two countries on two continents I had never been to, with languages I didn’t speak, and that terrified me.

I independently found an opportunity in Cameroon and begged them to let me go. I spent five warm months in the familiar shade of banana trees, drinking my favorite hibiscus iced tea, eating fresh mangos, speaking French and English, and taking the same brand of malaria prevention pills I had taken in Senegal. A more courageous woman would have gone with the other options, braving steeper linguistic and cultural challenges. I chose my comfort zone.

To be honest, when I moved to Alberta, Canada, at age twenty-one, I was far more apprehensive.

I seriously questioned whether I could withstand Alberta’s brutal winters. Winter is about six thousand miles from my comfort zone. Give me the choice between the occasional tarantula found in the house or having to scrape ice off my car in negative-forty degrees Fahrenheit and I will pick the tarantula every time. I wouldn’t necessarily say I prefer sub-Saharan dust storms over prairie snow squalls, but I certainly have more experience with the dust. I’m a homebody at heart. I have no ambitious plans to backpack around Europe or hike the Himalayas. I don’t see myself ever visiting Machu Picchu or camping in the Australian Outback. At restaurants I don’t order calamari or frog legs “just to try it at least once.” I am not eager to use Duolingo for five weeks and then head out on the streets of Seoul to practice my Korean.

An unexpected houseguest, Eastern Cameroon

“

In the TCK world, you might as well call me ‘adventure-averse.’”

But I am about to move for the ninth time in a period of eight years. I know exactly three people in my new city. I’m leaving in one week, I signed a lease for a studio apartment I’ve never seen in person, and I’m only taking what will fit in my small car for the two-thousand-mile drive.

Haddie throws boiling water into the air, December 27, 2021. Windchill index on this day reached -56°F (-48°C).

One of my most exciting stories from my time in Alberta is the story of my first (and only) moose encounter. A young bull quietly and uneventfully crossed the road in front of my slow-moving car and I did not shut up about it for a year. I told that story with the same enthusiasm you would expect from someone who had climbed on its back and rode all the way to Saskatoon. In the TCK world, you might as well call me “adventure-averse.”

I’m going to attend a graduate program at a university I’ve never visited—the only program I applied to because it was the only one I was truly excited about, so I figured it was this or nothing. I have no idea what I’m going to do once I graduate, or even what country I’m going to live in.

But I’m a TCK, and TCKs know all too well that sometimes staying in our comfort zone is not an option. So, you take a picture of the tarantula and text it to your mom with no caption (for fun). You learn about car block heaters and down-filled parkas and the magic of merino wool. You use Google Street View to check out your new neighborhood on the other side of

the country and map out the transit routes for your daily commute. And then, when it all gets overwhelming and exhausting, a well-timed spoonful of budget-friendly, generic brand chocolate hazelnut spread brings you back. I’m a TCK. And I love my comfort zone. But I don’t get to live there, and I don’t really want to. I’ll adapt and adjust and I’ll figure things out along the way. I know I will. I always do. And when I look back, this part of my story may not be nearly as thrilling, fulfilling, or momentous as the time I encountered a moose in central Alberta (did I tell you about that??), but I guess that’s a risk I’ll have to take.

Haddie Grace has US citizenship, grew up in Senegal, graduated from university in North Carolina, met her Québécois husband in Cameroon, and immigrated to Canada in 2019. She currently lives in Montréal, where she is a full-time PhD student.

A TCK is an individual who, having spent a significant part of the developmental years in a culture other than the parents’ cultures, does not have full ownership of any culture. Elements from each culture are incorporated into the life experience, but the sense of belonging is in relationship to others of similar experience.

– David C. Pollock

by Elizabeth Liang

by Elizabeth Liang

Alien Citizen: An Earth Odyssey is like an anthem for those who grow up internationally, but its genius has thus far escaped the attention of the international school community. Elizabeth Liang’s gripping film and performance is a godsend for international educators grappling to find creative ways to address difficult, complex issues relating to racism and inequalities that speak to both children and adults.

Written and produced by Liang, Alien Citizen opens with a booming voice taunting her on stage to answer the unanswerable questions that third culture kids and mixed-race children often hear: “Where are you from? … What are you?” It then follows Liang’s childhood of moving internationally with her “Guate”-Chinese-IrishEuropean-hodgepodge-American family, partly to escape the civil war in Guatemala in the 1970s at first, and then later as a “business brat” when Xerox posted her father up, down, and across the Atlantic Ocean.

Liang—the sole actor in Alien Citizen—seamlessly switches from one character to another as she humorously unearths a hoard of deep-seated

pain that many children experience but have no words with which to express. After moving to Fairfield County in Connecticut, USA, she notices that “Nobody on TV looks like me, except maybe Spock on the Star Trek reruns!” Just as Liang is feeling culturally displaced and needing a sense of belonging, she begins losing her Spanish, the language that connected her to her father’s large and loving extended family in Guatemala.

But she does not stop there. Liang deftly places those same issues that have been covered myriad times in expat memoirs squarely in the middle of a world riddled with social inequalities spanning across centuries. Liang spares no one from critique, not even herself.

shows that when children are overwhelmed by language barriers, they sometimes express it in ways that look like the behavioural problems of a spoiled, privileged brat, such as by punching their classmate or yelling “Shut up!” at their teacher (Tanu, 2018).

It is not lost on the adult Liang that “Filomena left her home in the highlands of Guatemala” out of poverty to take care of her privileged family in “the coldest, unfriendliest town in New England.” Later, Liang alludes back to Filomena as she makes fun of her beloved Chinese Guatemalan family elders who were horrified by the dark tan she had picked up from playing in the sun at her next home in Panama because they were “obsessed” by anti-indigenous colorism (see Knight, 2015).

Liang’s brilliance lies in her ability to convey the child’s deep sense of loss at the exact same time she exposes the absurdity of the prejudice borne out of vast global inequalities. While many with similar international childhoods to hers struggle to go beyond addressing identity or transition issues in generic terms, it is not so for Liang, who is far too talented and fiercely honest for such a myopic focus.

A teenage Liang realises how tender she feels towards Egypt when she witnesses a group of Egyptian boys playing soccer appearing helpless in the face of one European boy taunting them with “fake Arabic.” Liang delicately addresses the ambivalent feelings that emerge when social class hinders a child’s desire to build meaningful relationships with the local community.

In a poignant scene, after trying and failing to speak Spanish to their housekeeper, five-year-old Liang takes a broom in an attempt to hit their housekeeper, Filomena, while her older brother tries to stop her. My own doctoral research

In high school, Liang becomes “excellent friends” with Hamed, a local student who does not “speak any language without a foreign accent”—not even Arabic, thanks to his international schooling— and seems out of place in Egypt despite having never lived anywhere else. According to the psychologist Dr. Doug Ota, “stayers” are often forgotten by school transition programs even though they are repeatedly left behind by “expat”

classmates who come and go as though through a revolving door (2014).

The goofy Hamed became my favourite character even though the Grease-loving Liang (Grease, the film) won’t dance with him at a school dance because he is not “cool”—never mind the fact that the teenaged Liang was just as awkward— because… high school is high school. Be prepared to cry and laugh (hard) at the same time.

The film is a dynamic viewing experience thanks to director Sofie Calderon and editor Daniel Lawrence. Shot at different angles in front of a live audience, the energy of the performance and the editorial pacing are top notch. Audio effects enhance the atmospheric storytelling while visual effects add welcome texture, with scenes changing to the sound of a Xerox photocopy machine.

What’s more, because Liang is a master storyteller of childhood emotions, international school students will instinctively pick up on the complex issues more than you might anticipate. In fact, Alien Citizen gives voice to what these students already know but are rarely invited to talk about. Indeed, it is a film that you “feel” as much as you see.

It was a crisp evening in March 2014 near Washington D.C. when I reluctantly dragged my jet-lagged body to the hotel ballroom of the Families in Global Transition conference to watch a live performance of Alien Citizen for the first time. I had initially thought, “What can one woman in a black T-shirt and jeans possibly do on a near-empty stage?” I entered late and slumped into my chair.

In all this, Liang never loses sight of the child bewildered by the constantly changing world around her. As she takes the audience with her from Guatemala to Costa Rica, the US, Panama, Morocco, and Egypt, we see a young child gradually shut down from “transition fatigue” as she turns into a teenager in her sixth country. All the while, her adolescent body is subjected to regular sexual harassment that she could neither fend off nor comprehend at that age. Covering everything from mobility, identity confusion, racism, class prejudice, and sexism to eating disorders, Liang distills the essence of these difficult and deeply personal experiences and presents them in a manner no scholar possibly could. And she does it with superb comic timing.

But by the time the stage lights faded on Liang to signal the end, a third of the 142 attendees were bawling out our eyes.

“It hit you hard, huh?” It was the American international school educator who had been sitting next to me. He looked amused. I was a dripping wreck of snot while he looked curiously as fresh as when he first sat down. So, I glanced around. The ones sobbing seemed mostly to be those who identified as having spent their childhoods “growing up among worlds.”

It was the first time we had heard our stories told with such compassion and brutal honesty.

*This review was first published in the EARCOS Triannual Journal Fall Issue 2022.

Alien Citizen: An Earth Odyssey is available on DVD and digital streaming in Individual (home use) and Institutional versions: www.aliencitizensoloshow. com. The DVD includes a Q&A with Elizabeth Liang and director Sofie Calderon, and interviews with Liang’s brother and parents. The Institutional DVD and Streaming License both include a digital toolkit with over 35 clips from the film, each followed by questions to promote learning and discussion.

Knight, D. (2015). What is colorism? Teaching Tolerance, Fall(51), 45-48. Retrieved from www. learningforjustice.org/magazine/fall-2015/whatscolorism

Ota, D.W. (2014). Safe Passage: How Mobility Affects People and What International Schools Can Do About It. Stamford, Lincolnshire: Summertime Publishing. www. safepassage.nl/the-book

Pollock, D., Van Reken, R.E. & Pollock, M. (2017). Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds (3rd ed.). Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing. (See also www. crossculturalkid.org)

Tanu, D. (2018). Growing Up in Transit: The Politics of Belonging at an International School. New York: Berghahn Books. www.berghahnbooks.com/title/ TanuGrowing

Danau Tanu, PhD, is the author of Growing Up in Transit: The Politics of Belonging at an International School. She is currently in Tokyo as a Japan Foundation Research Fellow at the Waseda University Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies (WIAPS). Learn more about Danau’s work at www.danautanu.com or via Twitter/Instagram @danautanu.

Elizabeth Liang (aka Lisa) is an actress, writer, producer, speaker, and workshop leader. Her onewoman show, Alien Citizen: An Earth Odyssey, toured internationally and is now an award-winning film. Lisa is an autobiographical storytelling workshop leader; published essayist; co-host of the longest-running podcast on the multiracial experience; bilingual actress on stage and screen; and keynote speaker on intercultural and intersectional storytelling. She grew up in Guatemala, Costa Rica, Panama, Morocco, Egypt, and Connecticut, and is a graduate of Wesleyan University.

Website: https://elizabethliang.com/HapaLis-Prods Instagram: @hapalis

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ AlienCitizenSoloShow/ Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/ interculturalstorytelling LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/elizabethliang-intercultural/

When it comes to the third culture kid’s personal characteristics developed via his or her unique childhood, there are aspects which can be seen as advantages and challenges simultaneously. One such aspect is adaptability as opposed to a lack of true cultural balance, which has led to the coinage of the term “cultural chameleon” (Pollock et al. 2017).

This can be related to sociologist Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical theory (1996), where life can be compared to a “play” one must engage in by taking on a certain role, depending on who one’s counterpart is at any given moment. An important part of socialization is learning how to behave in certain situations or, to put it in terms TCKs know well, becoming a cultural chameleon. To avoid standing out and being different in their host cultures, TCKs quickly learn to adapt to new cultures by learning their languages or by changing their appearance and cultural practices, for example. According to Goffman, this adaptation process can be referred

to as “impression management.” TCKs do this to better blend in with their new environments so they are not seen as outsiders. This character trait does not just help them survive the struggles of their daily interactions in new places but can also be very useful and beneficial to their later lives as they can easily adjust to new schedules and changing circumstances and switch between cultures as quickly as necessary (Pollock et al.). Research has even suggested that TCKs themselves “describe their capacity to adjust as cultural understanding, attitudinal robustness and a belief or self confidence that they will be successful on future international assignments” (Westropp et al. 2016).

However, this skill of quickly being able to adapt to new cultural environments can also lead to the challenge of not experiencing a sense of true cultural balance. While they may externally appear to fit in with the crowd and culture surrounding them, the individual may internally be going through a challenging process of trying

to understand the new culture, always wondering if they are giving a convincing performance within their life’s play or not.

Additionally, TCKs may “have trouble figuring out their own value system from the multicultural mix they have been exposed to” (Pollock et al.). This means that it may be hard for them to differentiate their own set of morals and convictions from those of the “hive mind mentality” of the culture they are in currently. This may also lead to a sort of identity crisis within TCKs, since they may not know what to believe or who they are, apart from their current cultural identity (Pollock et al.).

Being TCK chameleons may not just present an internal struggle but also may attract skepticism from people surrounding them. Since others could observe them while they are switching cultural practices from one moment to the next, TCKs may come across as untrustworthy. TCKs might struggle to control their manner of interacting and the image they are emanating, which can clash with their idea of impression management. This can make it difficult for them to convince people of their authenticity, since they may tend not to be completely familiar with their current culture in a way that seems natural to observers. Since TCKs are seemingly characteristically unpredictable, it could be hard for people with more culturally conventional backgrounds to understand how their upbringing may have influenced their behavior in this regard.

Due to their status as cultural chameleons, however, TCKs may develop the characteristic of an expanded worldview. Because of their internationally mobile upbringing “[t]he TCK’s awareness that there can be more than one way to look at the same thing starts early in life” (Pollock et al.). They experience cultural differences around the world firsthand while also being able to observe people viewing life from many different perspectives philosophically, politically, and socially (ibid.).

However, this wide range of perspectives can also lead to TCKs developing confused loyalties regarding “such complex things as politics, patriotism, and values” (ibid.). They could, for example, not know which country to be supportive of during world sports, be conflicted when supporting their home country’s policies if they might harm their host country, or maybe not know how to react when friends talk badly about the other country they feel loyal to in one way or another (ibid.).

Furthermore, it can be argued that TCKs do not necessarily feel a sense of belonging within a nationality or place but rather by having “a community, an ‘interstitial culture’ to which they belong” (ibid.). Research has indicated that their “sense of belonging [is] three times stronger to relationships than to a particular country” (Fail et al. 2004). Since they may not have a “sense of home” in the classical definition of the term, they often find other ways to determine their belonging independent from geographical borders (Pollock et al.; Westropp et al.).

TCKs are also said to identify more often with their school surroundings than with their parental home environment while growing up (Fail et al.). The reason for this may be that they are often sent to boarding schools (Pollock et al.), where they spend most of their upbringing, but also due to the fact that the school and the educational environment in general represent the Third Culture for many. It seems to be the case that no matter what approach one takes analyzing third culture kids, it always leads back to them feeling most comfortable within the Third Culture itself, creating their cultural identity through shared experiences with other TCKs and a mixture of both their home and host countries.