Liz Hirsch

If we can, let us imagine emptiness recalibrated, space unfolded toward smooth and slippery and nonconforming use. American cities, in particular, are full of overstuffed assemblages waiting to be unpacked.

—Jill Stoner, Toward a Minor Architecture

A fold is always folded within a fold, like a cavern in a cavern.

—Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque

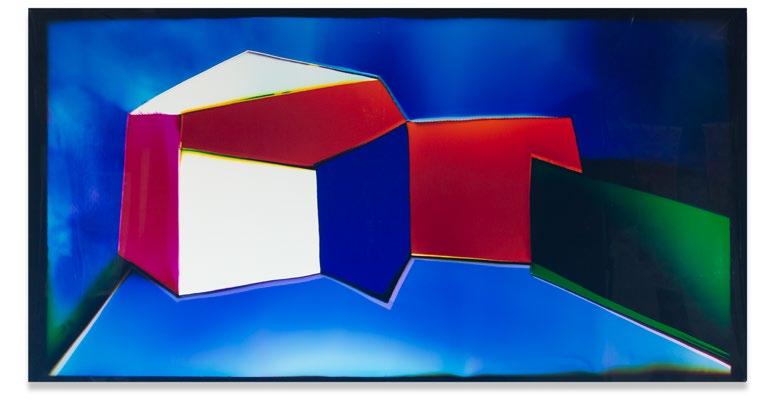

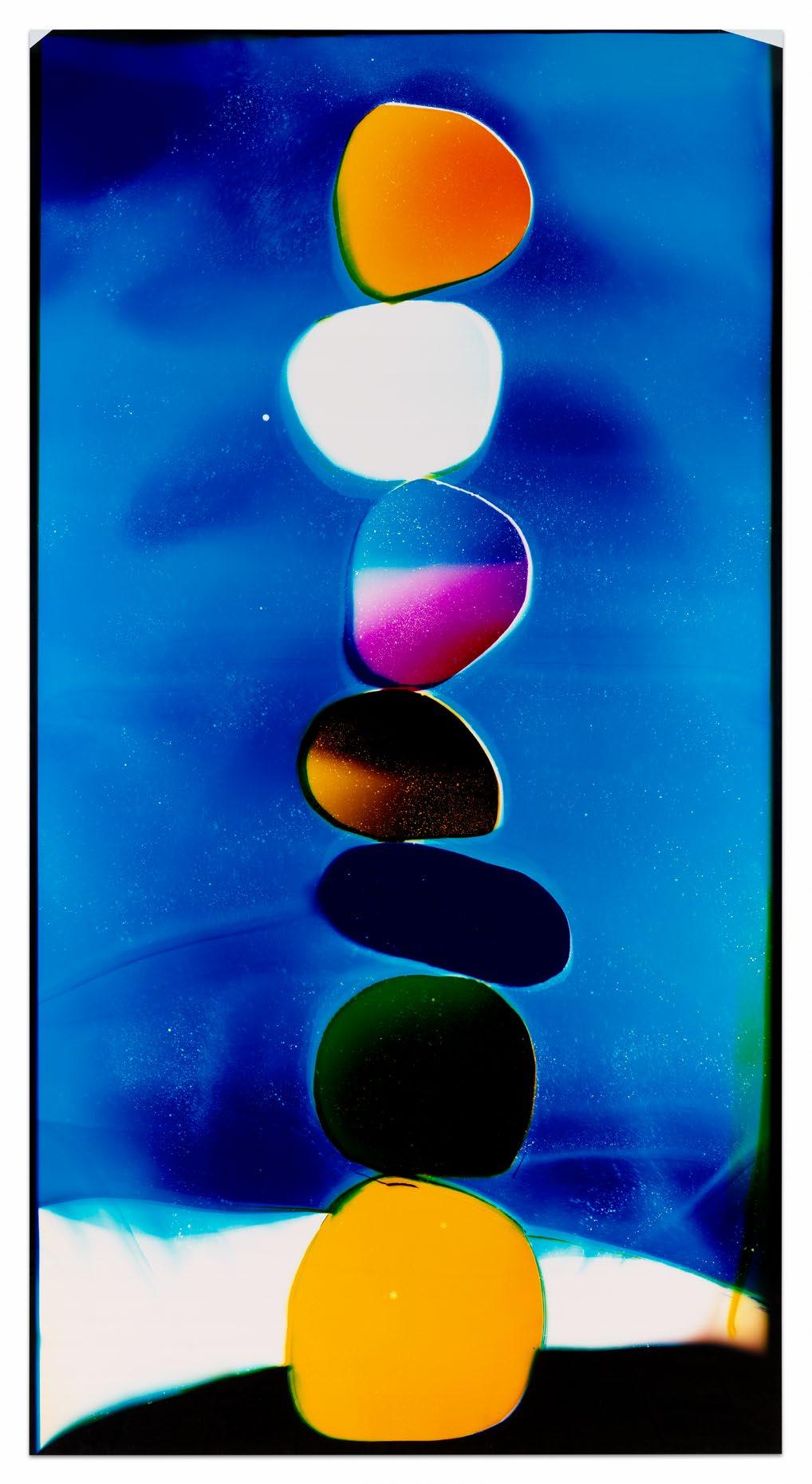

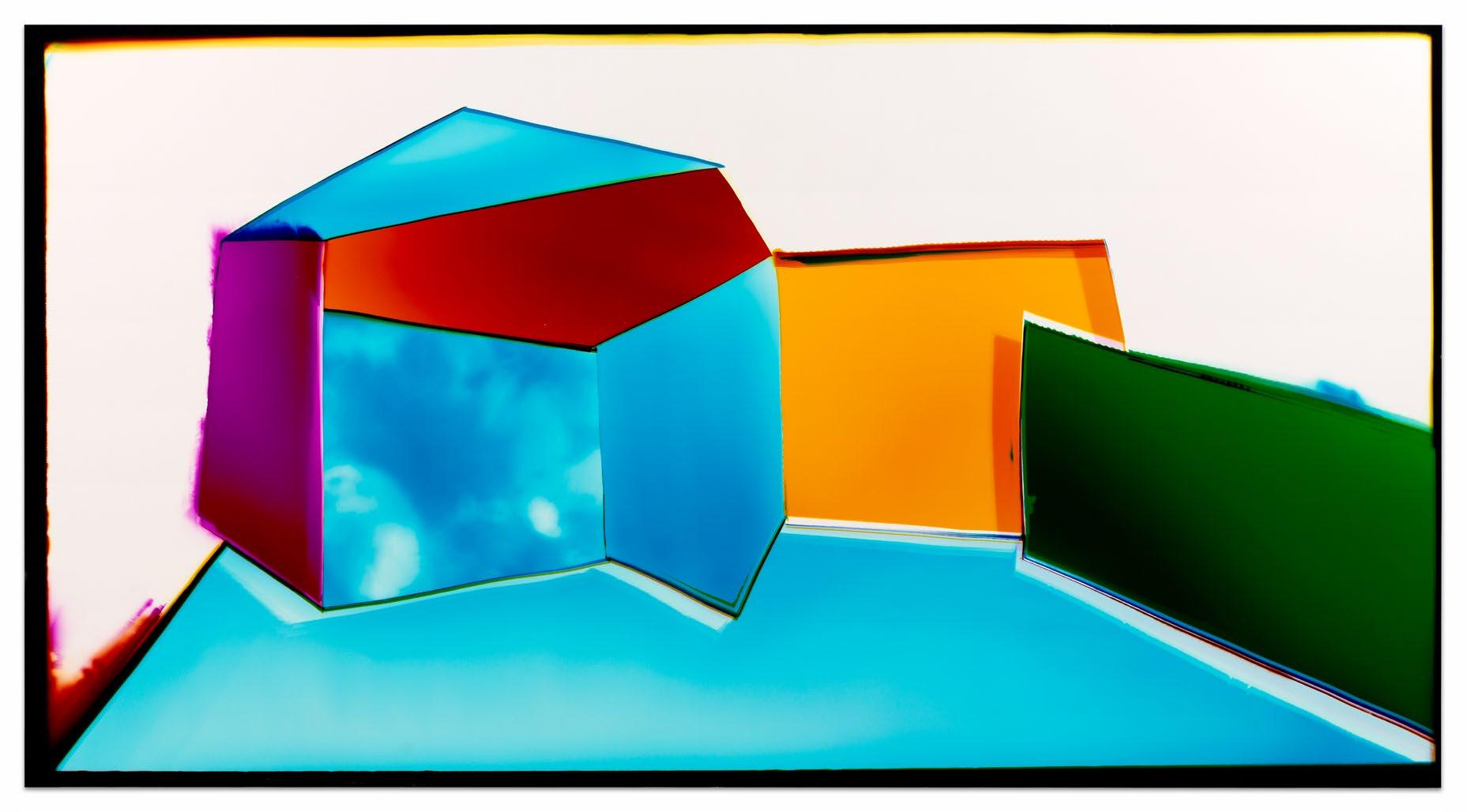

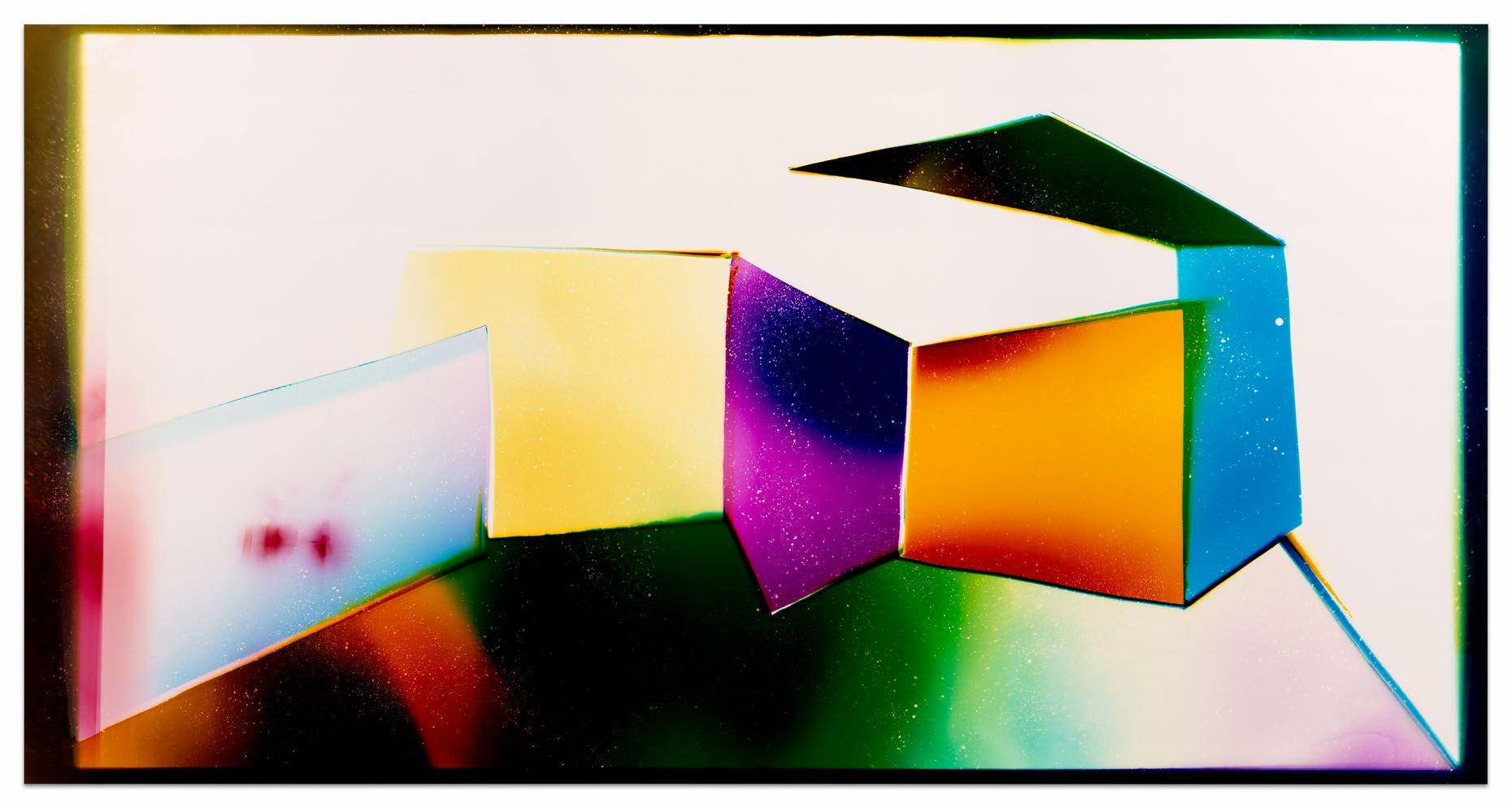

In a nondescript landscape, a sequence of planes appears: magenta, white, navy, crimson, then hunter green, all set against a cerulean expanse (fig. 1). The colors pulsate with vivid intensity—the planes angling in and out like architectural pleats, forming structures reminiscent of walls and a roof. Liz Nielsen’s Folded Architecture series of photograms evokes built space through a medium that paradoxically requires no building. Here, interiority and exteriority blur, suggesting a perpetual folding of spatial dimensions that echoes the philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s conception of the baroque: a way of understanding existence as a fluid, interconnected process rather than a fixed essence.

Through its unique photographic process, Nielsen’s work embodies the material traits of folding that Deleuze identified. It simultaneously conjures what Jill Stoner describes as a “recalibration” of space. In doing so, Nielsen offers a formal exploration at the intersection of painting, photography, philosophy, and the built environment, challenging our perceptions of how space can be imagined, represented, and experienced.

Nielsen’s images represent a significant departure from traditional photographic techniques. In an analog darkroom, she produces cameraless images using a process best described as light painting or photograms. The method has evolved from the early days of 19th-century photography (Greek for drawing with light), when pioneers like William Henry Fox Talbot produced “photogenic drawings” that recorded the delicate branching of plant stems or whorls of lace. In the 20th century, surrealists like Man Ray and Maurice Tabard experimented with using the photogram to assemble layered, multivalent images often predicated, sometimes to a sinister extent, on the objectification and fragmentation of the female body.

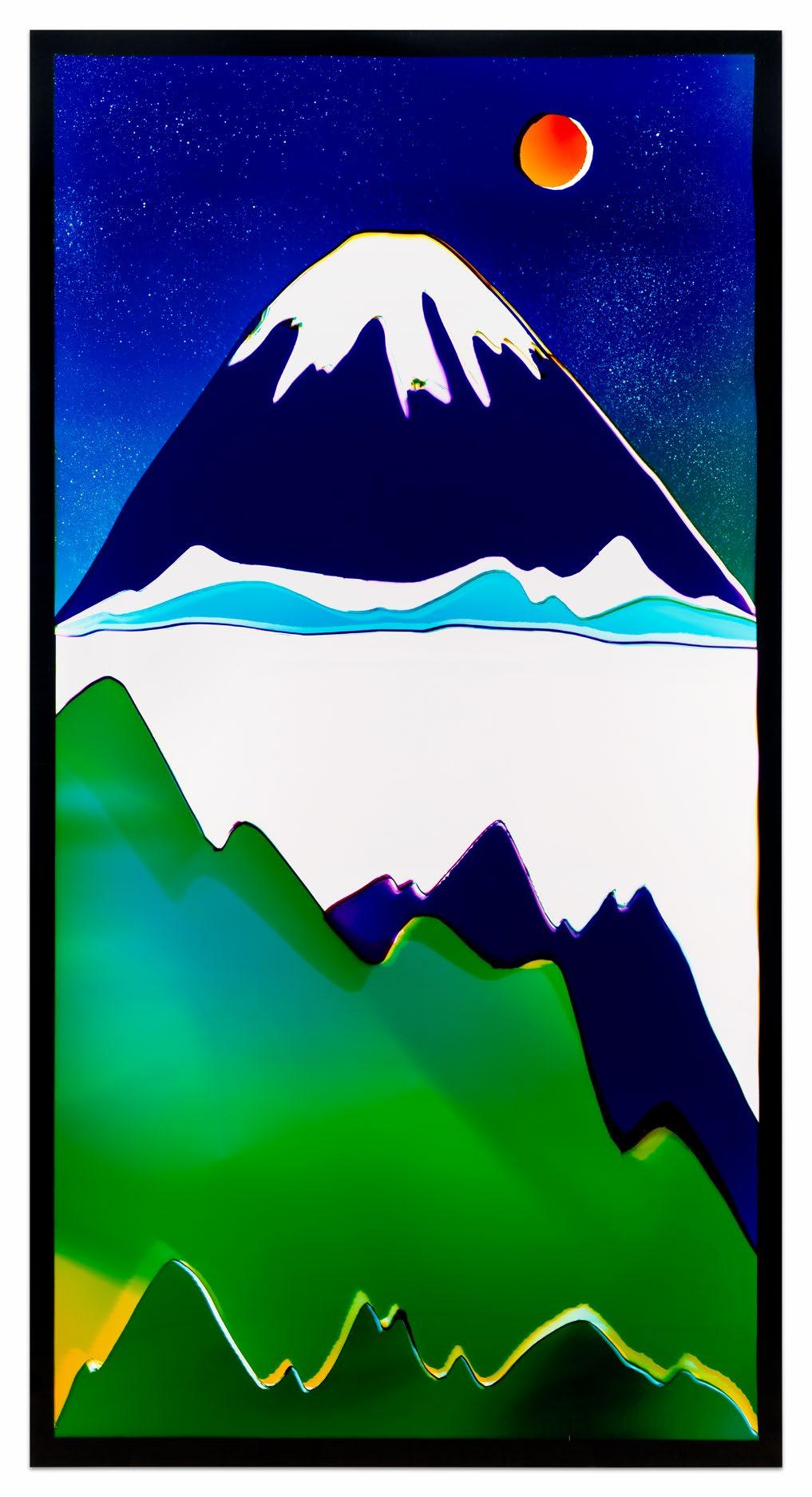

Nielsen’s Folded Architecture (2024, fig. 2) is another Folded Architecture image that mirrors the composition mentioned above. The palette differs: a teal infused with yellow, gold, plum, royal blue, and an emerald green that the artist explains is particularly tricky to achieve, as one must negotiate the extremes of the visible spectrum. Here, the “sky” is a flat white tinged with grey.

The shapes again amount to a simple arrangement of planes on a horizon—a collection of imaginary buildings; of smooth, impenetrable surfaces reflecting light.

While photograms have traditionally been intimate in size—such as Talbot’s prints or, fast-forwarding to the 1980s, the collage-based photograms of Mark Morrisroe—Nielsen’s photograms are large. Her 50-inch silver halide prints augment the genre. The scale shift challenges our perception of photography’s relationship to spatial reality, and a focus on composition is maintained. Nielsen is not alone in her use of photograms. Wolfgang Tillmans prints abstract cameraless images, sometimes at a monumental size, though his surfaces are often marked with luminous washes of color that convey weightlessness. Other contemporary artists like Mariah Robertson or Josh Kolbo utilize cameraless photography to explore the limits of its materiality. Liz Deschenes mines its capacity for producing unique optical effects. Within such company, Nielsen focuses on spatial composition and an expression of crystalline form and color to create a distinctive narrative.

Light is both essential and anathema to the darkroom—the domain for Nielsen’s careful manipulation of light and shadow—and this tension is Deleuzian in another sense. Deleuze describes a black marble room as the baroque architectural ideal: “... light enters only through orifices so well bent that nothing on the outside can be seen through them.…” This space of controlled illumination, where Nielsen stages her compositions, parallels the philosopher’s concept. Further, Nielsen’s imagery in the Folded Architecture series—opaque structures without windows or doors—extends the spatial metaphor into a symbolic register.

Paul Klee’s color-gradation pictures from the early 1920s correspond to his experience as an instructor at the Bauhaus, where he emphasized color theory. However, in works like Three Houses (1933, fig. 3), shape and line are equally significant, two elements Deleuze saw as indicative of Klee as a kind of modern baroque artist. Klee’s approach to space and form, particularly in his architectural subjects, offers a precedent for Nielsen’s Folded Architecture. Both artists create a sense of depth and movement through the interplay of color and geometric forms, challenging traditional notions of perspective and representation.

Fig. 3 Paul Klee, Three Houses, 1922, Watercolor on paper, bordered with watercolor, 7 7/8 x 11 7/8 inches (20.1 x 30.2 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Berggruen Klee Collection, 1984.

In Nielsen’s work, this Klee-like sensibility is evident in how she constructs the picture’s premise. For instance, the planes of color in Folded Architecture (2024, fig. 2) echo Klee’s abstracted buildings, creating a similar sense of spatial ambiguity and rhythmic composition. Nielsen’s use of color gradients and sharp geometric forms recalls Klee’s technique of building complex visual structures from simple elements, a practice Deleuze identifies as quintessentially baroque in its multiplicity and continuous variation.

When one looks closely, Nielsen’s prints sometimes reveal a subtle but crucial element: an atomized layer of “visual snow” across the image. This speckled texture adds depth and dimension to a schema ostensibly defined by flatness. It creates a sense of vibration or potential movement—as if the forms could shift or reconfigure, aligning with the fold, per Deleuze, as a state of perpetual becoming.

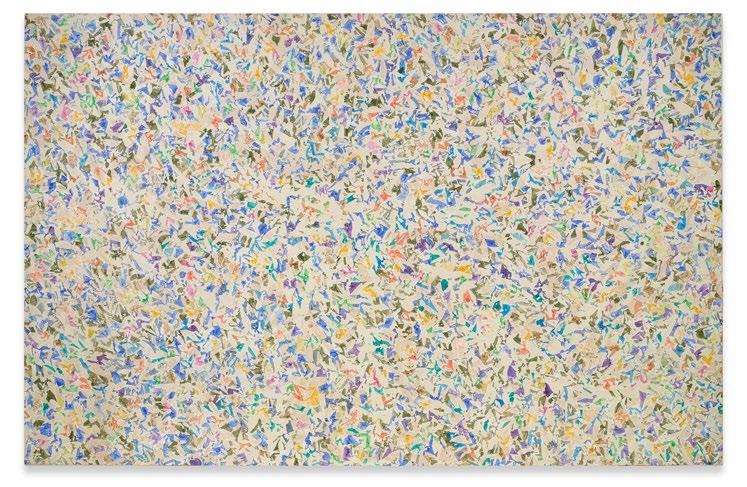

The pliage, or deliberate folding, of Simon Hantaï presents another possible point of comparison. Hantaï, whom Deleuze fondly identified as a proponent of the fold, took a highly technical and tactile approach to figure and ground (fig. 4) in a way reminiscent of Nielsen’s approach.

Fig. 4 Simon Hantaï, Untitled (Suite “Blancs”), 1973, Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 120 1/4 x 183 inches (305.3 x 466.5 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, Acquired through the Carol Buttenwieser Loeb and Arnold A. Saltzman Funds.

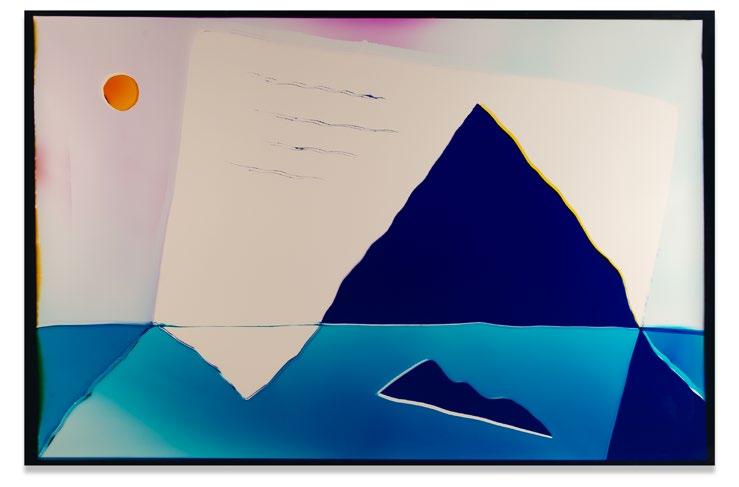

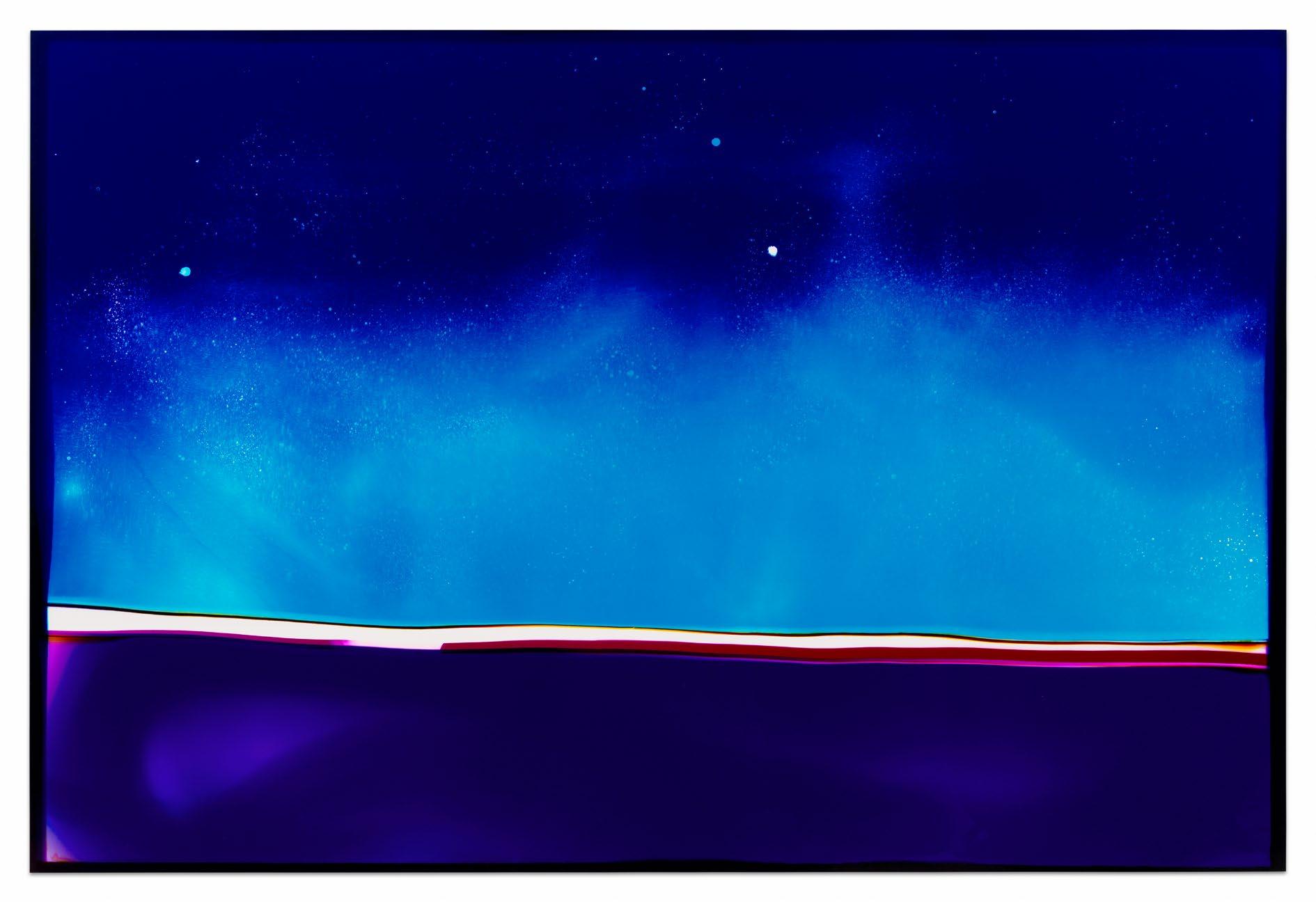

5 Liz Nielsen, Notebook Landscape, 2025, Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique, 50 x 73 inches (127 x 185.4 cm)

Hantaï’s method of folding, painting, and unfolding canvas created works that blurred the distinction between positive and negative space, much as Nielsen’s photograms blur the line between light and shadow, figure and ground. Questions around authorial control—and the modernist preoccupation with how much to let chance determine one’s outcome—also pervade these practices. Nielsen’s work, like Hantaï’s, embraces a degree of chance and material agency, allowing the properties of light and photo- and chromo-sensitive paper to contribute to the final composition in ways that are not entirely predictable.

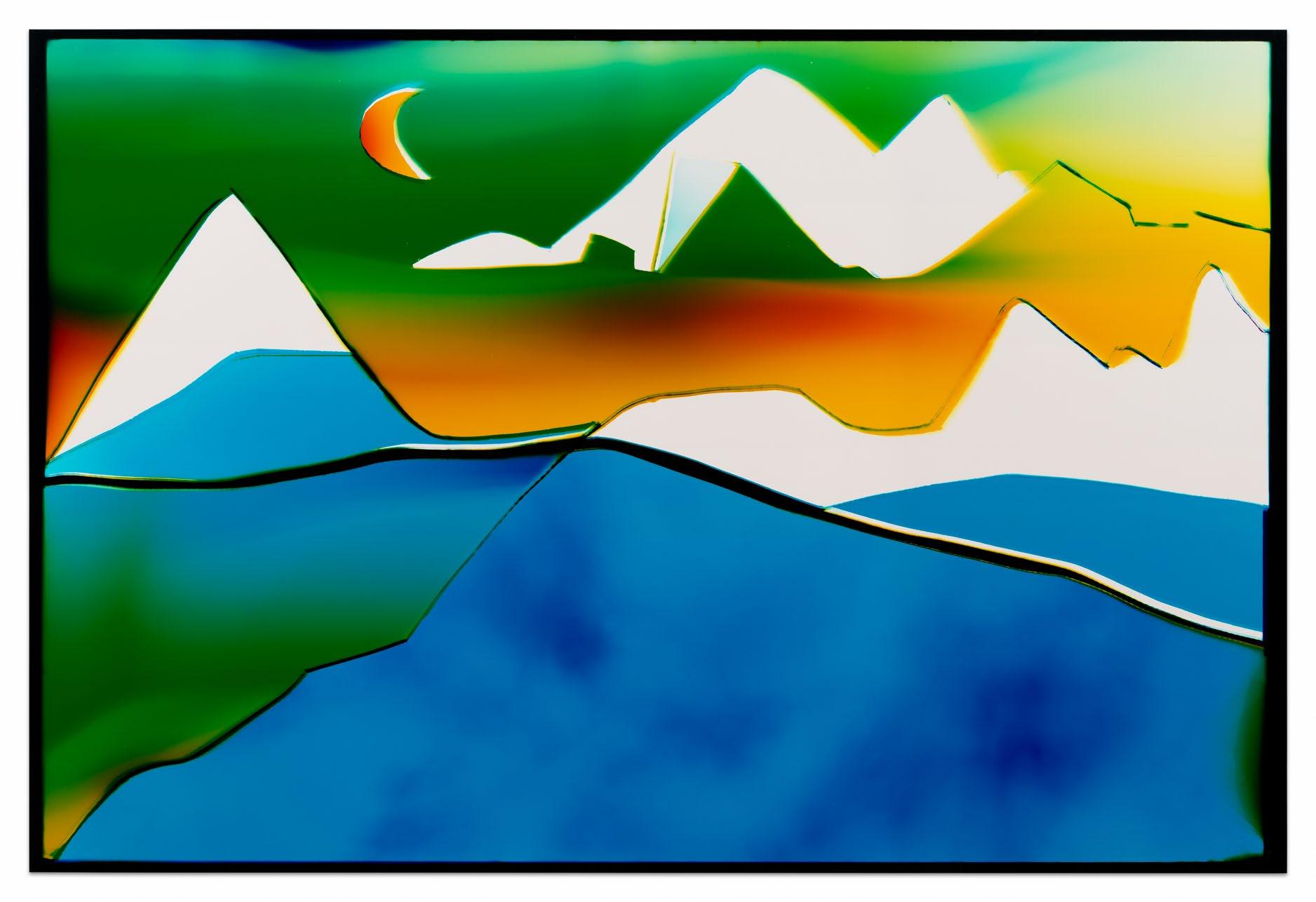

This element of unpredictability is further explored in Nielsen’s iceberg composition Notebook Landscape (2025, fig. 5). Here, the artist presents a striking visual metaphor for folding in physical and conceptual space. The image depicts a horizon line separating a blue-pink sky from water (comprised of various blue shades). A navy-blue triangle emerges from the water, and a white rectangle (perhaps a square of light) backs the triangle and appears to plunge into the depths. A small, round, orange sun occupies the upper-left corner, seemingly illuminating the scene.

In this work, Nielsen achieves a different kind of folding, one that collapses the distinction between figure and ground, surface and depth. The geometric forms—triangle, rectangle, circle—become abstract signifiers of landscape elements, their relationships shifting and folding into one another. This visual strategy recalls the fold to understand the relationship between the inside and the outside, the visible and the hidden. The constructed nature of the landscape stands out to us; we are aware of its artificiality, of the limits of its denotation.

An image of an iceberg adds an additional temporal dimension to Nielsen’s exploration of folded space. The sun, positioned high in the frame, suggests a moment of transition—perhaps dawn or dusk—implying the folding of time into the spatial composition. This adds another layer to Nielsen’s engagement with spatial arrangements, suggesting that her Folded Architectures not only reconfigure space but also fold time into the abstract.

Within her broader compositions of color and form, Nielsen incorporates moments of literal in-darkroom “light drawing.” These precise, linear elements of the work contrast with the work’s more prominent color fields, creating a beautiful interplay between different modes of photographic mark-making. This technique emphasizes the constructed nature of these landscapes, reminding viewers that the landscapes are not renderings of actual locales but are carefully crafted visions of potential space.

Nielsen describes the aforementioned double landscapes as “entangled pairs.” These side-byside photograms exhibit bilateral symmetry and generate associations with the natural world. This approach to duality draws inspiration from the concept of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon believed to have been described as “spooky action at a distance” by Albert Einstein. The theory asserts that one particle of a once entangled pair will continue to connect with and rely on the other regardless of how much distance separates them. Recent experimental proof of quantum entanglement adds a layer of scientific relevance to Nielsen’s artistic exploration of this poetic link.

Returning to Stoner, her concept of “minor architecture” provides a valuable framework for understanding Nielsen’s recent practice. Drawing on Deleuze’s and the philosopher Félix Guattari’s notion of “minor literature,” Stoner proposes an architecture that emerges from the margins, challenging dominant structures and narratives. Nielsen’s photograms, with their reimagining of space through light and color, resemble works of architecture proposing alternative ways of conceiving built and organic forms. The artist relates this to the cruising ground, or the cruising pathway, that anonymous zone of intimate physical contact and resistance to the confines of entrenched heteronormativity.

Nielsen pushes boundaries; she makes work that tests our understanding of space, light, color, and representation. Hers is a semi-baroque sensibility, one marked by layered exposures and enigmatic spatial relationships that contribute to a sense of infinite folding. In this way, the artist offers a coherent perspective on how we might both build and escape from new working forms.

Liz Hirsch is a writer and art historian based in Los Angeles, California. She is an Assistant Professor of Contemporary Art/ Media Studies at Otis College of Art and Design. She holds a Ph.D. from The Graduate Center, CUNY, and specializes in contemporary art, cultural intersections, and artist networks. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Hyperallergic, Art in America, ARTnews, The Brooklyn Rail, and Frieze

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

97 1/2 x 52 3/4 inches

248 x 134 cm

Sea, 2024

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

53 3/4 x 78 inches

137 x 198 cm

Stone Arch, 2024

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

53 3/4 x 71 1/2 inches

137 x 182 cm

Folded Architecture (Cloud), 2024

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

44 x 77 1/2 inches

112 x 197 cm

Folded Architecture (Mysterious), 2024

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

43 3/4 x 80 1/2 inches

111 x 205 cm

Mountain of Consciousness, 2024

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

87 x 47 1/2 inches

221 x 121 cm

Landscape in the Sky, 2025

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

53 1/2 x 78 inches

136 x 198 cm

Moonlit Lake, 2025

Analog Chromogenic Light Painting, on Fujiflex, Unique

53 3/4 x 78 inches

137 x 198 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

20 March – 3 May 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery 511 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2025 Liz Hirsch

Photo Credits

p. 6: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY p. 7: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-4670-9

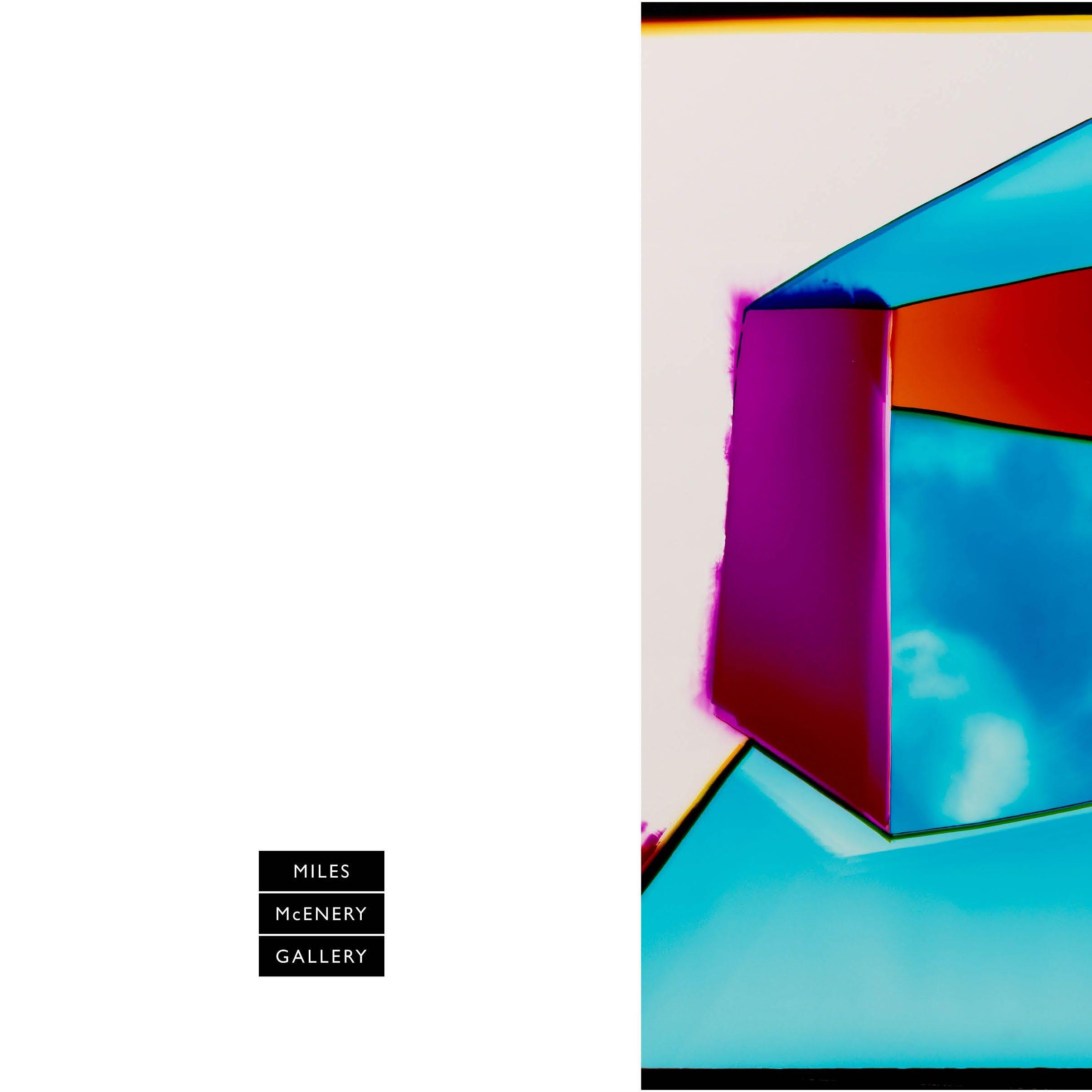

Cover: Folded Architecture (Cloud), (detail), 2024