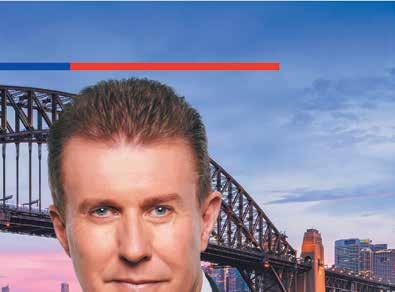

Sydney Harbour

What’s below the surface?

Captain Cook

A culture of music and dance

Cruising with COVID-19

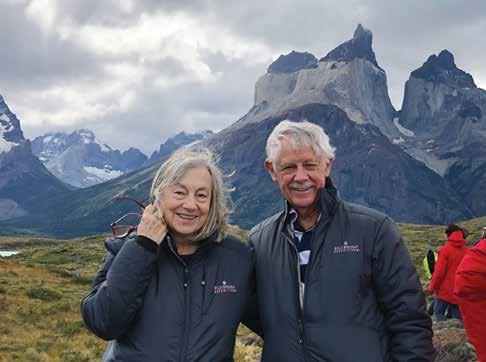

Lockdown off Chile

Sydney Harbour

What’s below the surface?

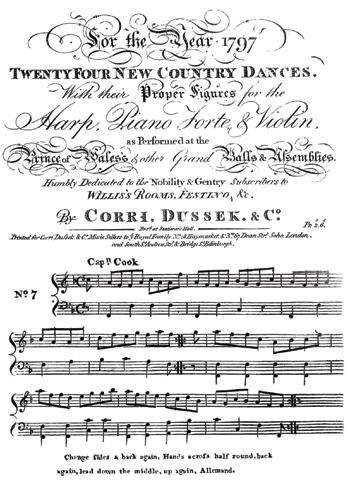

Captain Cook

A culture of music and dance

Cruising with COVID-19

Lockdown off Chile

Volunteers give more than 60,000 hours of service per year to the museum, both at our Darling Harbour site and across Australia. Pictured (from left) are Bronwyn Fitz, Gavin Napier, Michael Ward, Merideth Sindel, Stephen Goh, Werner Obernier and Kel Boyd. Image Andrew Frolows/ANMM

SINCE OUR TEMPORARY CLOSURE IN MARCH, I have spent much time thinking about what the museum world will look like in a new age of social distancing. Our museum has enjoyed many years now of growing audiences, revenue and reputation. But what will the recipe for success look like going forward?

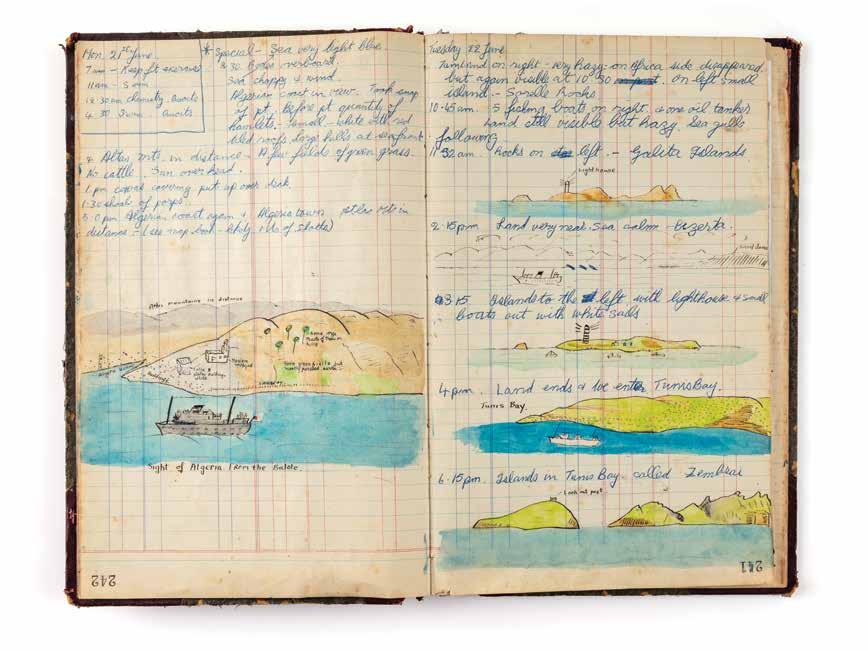

Traditionally, museums build reputations by excelling in four areas: curating unique collections, creating inspiring architecture and designing outstanding exhibitions, all of which are the creative and intellectual product of the fourth ingredient –passionate, dedicated and knowledgeable staff and volunteers. When blended together, these ingredients create truly memorable experiences for all our visitors. Without doubt we have expanded our collection, particularly in the Indigenous contemporary art arena, and acquired wonderful major pieces like the Bradley Journal and the magnificent SY Ena Architecturally we have enhanced Philip Cox’s masterpiece with a new foyer and Northern Gallery exhibition space and the award-winning Warship Pavilion by FJMT. We have had so many memorable exhibitions that it seems unfair to mention just a few, but my personal favourites have been Gapu-Monuk Saltwater – Journey to Sea Country, Bryant Austin’s stunning photographs in Beautiful Whale and the spectacular Escape from Pompeii: the untold Roman rescue. Wandering through the empty galleries while the museum is closed, it’s clear to me that there is still something missing other than visitors. What is lacking is that often-indefinable attribute which distinguishes one museum from another – or, in marketing jargon, our unique selling point. Some might say it’s the museum’s position on the water in Darling Harbour; others might point to HMAS Onslow or our replica HMB Endeavour. And while these are certainly vital ingredients, for me the museum’s unique spirit has always come from our staff and volunteers. The creativity, warmth, generosity and passion found in our galleries are a direct reflection of the makers and interpreters of these experiences.

So as I pass through our silent, empty foyer, I find myself smiling as I imagine again the hearty greetings, happy voices and warm invitations, particularly of our army of volunteers.

The museum’s 1,000-plus volunteers are based not just in Sydney, but right around Australia. All are ready to spring into action whenever Endeavour visits or when one of our travelling exhibitions lands in their home town. Every day 30 to 40 volunteers turn up at the museum to greet and inspire our visitors and, importantly, to carry out an enormous range of behind-the-scenes work. The museum’s volunteers are part of a massive army of more than six million volunteers across Australia who each year give their time, energy and dedication so freely to organisations like ours.

Each day begins the same for all of the museum’s volunteers, with an early-morning briefing. To listen to their banter, you know instinctively they are each other’s best friends, and sometimes much more – they are family. The chemistry, ribbing and hilarity are constant and an indelible part of the museum’s unique spirit. So as I look to the future and contemplate the museum’s reopening, it’s our wonderful volunteers that I most look forward to seeing and hearing again.

Kevin Sumption psm Director and CEOFor information on how COVID-19 has affected the museum and its events, and for details about online exhibitions and programs, please see pages 28 and 44–48.

Acknowledgment of Country

The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the Traditional Custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all Traditional Custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language. Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Number 131

Cover Discarded motorbike in Cabbage Tree Bay Aquatic Reserve, Sydney. Image Justin Gilligan

2 Submerged secrets

Sydney’s thriving waterways

10 Stories of migrants and members

Membership and Foundation news

14 Tasmania’s spotted handfish

Ceramics and science collaborate to save an endangered species

20 Cruising with COVID-19

A Member’s story of lockdown and escape

28 We’re reopening soon! A message from the museum

30 Dancing with Cook

Music and dance in Cook’s life and times

34 An eccentric curriculum

Crafting larrikins aboard the Nautical School Ships Sabraon and Vernon

42 ‘Not all beer and skittles’

Sydney’s marine pilots

44 Museum events for winter

Your calendar of online talks and family activities

46 Winter exhibitions

What’s online now and being planned for our reopening

50 Maritime Heritage Around Australia

Reconciliation Rocks, Cooktown, Queensland

54 Collections

Colonial aquatints; Indigenous contemporary art

64 Education

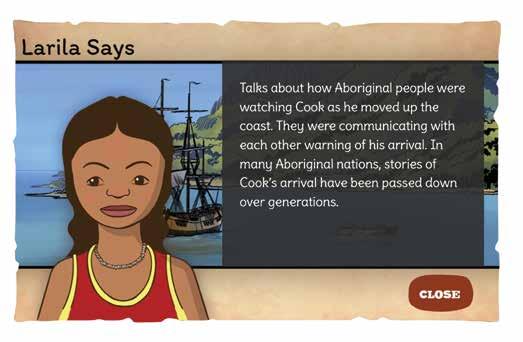

Museum educators; Cook’s Voyages Game

70 Tales from the Welcome Wall Faith, family and a warm welcome to Australia

74 Readings

My Cathedral in the Sea: a History of the Conway by Harley Stanton

76 Currents

Remembering the Christchurch attacks; vale George Bambagiotti

Beneath the surface of Sydney’s waterways and coastal strip is a surprising and wild marine metropolis waiting to be discovered, writes photojournalist and marine biologist Justin Gilligan.

It’s a dark, shadowy world in Sydney’s swimming enclosures and beneath the city’s jetties

SYDNEY’S SUN-SPANGLED WATERS are central to the city’s national and international reputation. But just how much life lies submerged, hidden away from the above-water pressures of Australia’s biggest city and its ever-sprawling human population, beneath our most iconic landmarks, beaches and headlands?

Geologically, Sydney Harbour is a river valley that was drowned as the sea level rose about 11,000 years ago at the onset of the present interglacial period. But from a marine ecology perspective, it’s one of the world’s most modified estuarine systems. Along with Port Hacking and Botany Bay to the south and Pittwater and the Hawkesbury River to the north, the harbour is one of a series of deep waterways in the Sydney Basin that all drain along a shallow coastal strip between Palm Beach and Cronulla.

Interconnected rocky reefs along this stretch of coast are separated by swathes of mobile sediment that have adapted to withstand large and powerful waves. In the shallows, these reefs are covered in forests of seaweed that shelter common sea dragons feeding on swarms of tiny mysid shrimp. Also living here are giant cuttlefish, which have pigment organs called chromatophores in their skin that change in an instant, both in colour and texture, to transform these behaviourally complex creatures from flamboyant billboards to masters of disguise. Down in deeper waters, the reefs are covered in a living veneer of colour created by gardens of sponges, ascidians and tunicates in all shapes and sizes.

Blue gropers are a recurring and much-loved element of Sydney’s coastal life, famed for their tame behaviour, large size (up to 40 kilograms), blubbery lips and peg-like teeth. Just one or two dominant males usually occur within an area, along with a larger number of females. When a male dies or moves away, the largest female changes sex to become a replacement male. Many of Sydney’s resident gropers – such as ‘Bluey’ off Clovelly Beach – have been affectionately named by adoring locals.

Seven aquatic reserves protect some of Sydney’s most accessible and biologically diverse coastal areas. Cabbage Tree Bay Aquatic Reserve at Manly is one of the most popular, where snorkellers can experience southern eagle rays, dusky whaler sharks and crimson banded wrasse, often swimming around the occasional discarded junk such as an old motorbike.

Within Sydney Harbour’s estuarine environments, waters are generally shallower, more sheltered and prone to the influence of tide and salinity. Here, softer sediments provide the perfect habitat for bizarre molluscs, polychaete worms, echinoderms and crustaceans. Three aquatic reserves also afford protection for some of Sydney Harbour’s estuarine habitat in Towra Point in Botany Bay and Shiprock in Pittwater.

Stands of marine vegetation – including mangroves, seagrass and saltmarsh – provide isolated oases for wading birds such as stilts and pelicans, and habitat for juvenile fish and marine invertebrates. Seven species of seagrass are known from Sydney Harbour, with most found at shallow depths in outer harbour areas. Knowing that mangroves have been a declining habitat worldwide, it’s reassuring to find that the total mangrove cover in Sydney Harbour has increased since European settlement.

Operation Crayweed’s Adriana Verges measures the growth of transplanted crayweed off Bondi Beach, an initiative working to restore this species along Sydney’s coastline.

02

The charismatic eastern blue groper is only found off south-east Australia, and is regularly encountered off Sydney’s rocky reefs.

Seven aquatic reserves protect some of Sydney’s most accessible and biologically diverse coastal areas

The harbour is one of a series of deep waterways in the Sydney Basin that all drain along a shallow coastal strip between Palm Beach and Cronulla

In contrast, however, the extent of saltmarsh has declined dramatically due to foreshore development, with only an estimated 37 hectares remaining.

These days the installation of marine infrastructure requires consideration of the marine environment through the planning and approval process. Developments over marine vegetation, for example, are heavily regulated, with significant penalties for unauthorised harm to plant species.

It’s a dark, shadowy world in Sydney’s swimming enclosures and beneath the city’s jetties. Differences in shade, orientation and water flow are strong drivers of marine plant and animal life around these artificial habitats. Such places have proved beneficial for species such as seahorses, which thrive on swimming enclosure netting as it provides increased food availability and refuge from predation.

Deeper in Sydney Harbour, the waters around Clifton Gardens are home to striate anglerfish. Perfectly adapted to the area’s soft sediment and low-lying sponge habitat, this species has exquisite camouflage and uses its fins like feet to walk along the seafloor. It also has a built-in lure for attracting prey and a large mouth to eat it. Common Sydney octopuses also occur here, their distinctive white pupils and orange-rust-coloured arms emerging from lairs under rock ledges.

Sydney’s marine environment is exposed to most of the threats faced by coastal cities globally, including habitat loss, foreshore development, pollution, stormwater run-off and introduced pests. But some plant and animal inhabitants appear to not only be coping with the shortcomings, but are also finding their own strongholds.

The harbour, for example, is extensively modified, with more than half of the shoreline replaced by artificial structures such as seawalls, jetties and piers. Researchers are now starting to deploy prototype structures in Sydney Harbour to better connect the built environment with the natural environment. An example is designing seawalls with niches and crevices to increase colonisation by marine species such as seaweed, barnacles, limpets and crabs. The design of these environmentally friendly seawalls makes them more like natural rocky intertidal areas, with increased habitat complexity and a gradually sloping face to dissipate wave reflection.

Sydney’s estuarine habitats have historically been polluted by industry, particularly shipping, resulting in a legacy of residual toxins trapped in sediment, notably in low-energy sheltered bays with limited tidal turnover. Some impacts have been so severe they still need to be managed today, such as a fishing enclosure cordoned off in Homebush Bay to prevent people from catching and consuming fish from that area.

There are a number of shipwrecks still visible in Homebush Bay, including the wrecks of colliers Ayrfield and Mortlake Bank, the tug Heroic, the steel boom defence vessel HMAS Karangi and several barges, dredges and lighters. These wrecks are the remnants of Homebush Bay’s former use as a shipbreaking yard, and have become overgrown by thriving mangrove thickets. The wrecks can be viewed from the shore from Bennelong Parkway at Homebush Bay and Bicentennial Park.

01

A veterinary surgeon at the Taronga Wildlife Hospital & Pest Control holds up a pied cormorant following surgery to remove ingested fishing hooks, visible in the x-ray.

02

Harriet Spark from Operation Straw inspires volunteers through organised beach clean-up events around Manly.

Sydney’s marine environment is exposed to most of the threats faced by coastal cities globally, including habitat loss, foreshore development, pollution, stormwater run-off and introduced pests

The quality of Sydney’s waterways improved significantly in the early 1990s with the relocation of coastal sewage outfalls to deeper offshore water. But it didn’t come soon enough for some species. Researchers blame poorly treated sewage and stormwater for the disappearance of a brown seaweed, known as crayweed, from Sydney’s coastline. The species occurs in shallow water, grows to a height of 2.5 metres and forms dense beds of spindly lime-and-yellow-coloured fronds. Historic photographs, herbarium records and early research observations suggest the species formed underwater forests between Palm Beach and Cronulla during the 1960s and ’70s.

Since 2011, a collaboration of researchers, students and community dive groups, known as ‘Operation Crayweed’, has been working to restore this remarkable underwater habitat to Sydney’s coastal waters. As a first step, Operation Crayweed began investigating the species’ importance as an ecological community. In areas of New South Wales further south, the team documented that up to 10 times more abalone was associated with crayweed, compared with other species of seaweed, and that crayweed also supports a unique community of invertebrates, whose absence is likely to have flow-on effects to other species in the ecosystem. The team’s findings were supported by evidence from Victoria that greater numbers of rock lobster are associated with crayweed than with other seaweeds. Recognising the importance of this marine plant, the team is now working to restore it along Sydney’s coastline.

It’s a testament to the health of Sydney’s waterways that they are home to the last mainland colony of little penguins in New South Wales. Its existence, in Sydney’s North Harbour near Manly, was kept a local secret for decades during the 20th century. As many as 70 penguin pairs arrive here between May and February to breed. It is one of more than 10 sites in the state where the species breeds, along with Lion Island in Pittwater.

Yet, according to staff of the Taronga Wildlife Hospital and Pest Control, debris has been identified as a major threat to the marine wildlife that end up in the hospital’s care, which includes penguins. They also regularly receive marine turtles that have swallowed plastics and shorebirds that have swallowed fishing hooks or have them embedded in their body or wings.

The team has documented plastics inside the intestines of turtles, such as plastic shopping bags – both single-use and biodegradable bags – and small plastics such as lids, ring-pulls and bait bags, as well as balloons and balloon string. These days, there are more plastics in the harbour, and with more humans come greater amounts of marine debris.

If the marine turtles that come to the wildlife hospital can be rehabilitated to the point of release, they are fitted with a satellite tag to monitor their survival and movement. Specifically, this technology is used to collect information on their migratory paths and determine habitat usage. Marine turtles are considered indicators of marine debris pollution and can be monitored fairly easily. Therefore, the team is working to identify vital feeding grounds and resting areas for these threatened species – information that can later be used to protect important habitats.

Marine turtles don’t return to their nesting beaches in tropical waters until they are more than 30 years old. The hospital’s tagging work has shown where and how these young turtles around Sydney spend their time before reaching maturity. Surprisingly, the turtles head into Pittwater and up the Hawkesbury River, which researchers now know are important feeding and resting areas for these animals.

Community groups around Sydney have recognised the significance of the marine debris issue and have passionately taken action into their own hands. ‘Operation Straw’ is one such volunteer-based citizen science project that collects plastic straws from Manly Cove, a popular dive site and hotspot for marine debris. The initiative was born when Harriet Spark began noticing discarded straws and plastics building up at her local dive site. Harriet finds that straws are the perfect starting point to convey the importance of reducing single-use plastics. She believes we can live without straws and other single-use plastics, and she has a strong belief in a future healthy marine environment for Sydney’s waterways.

In Harriet’s own backyard, the Cabbage Tree Bay Aquatic Reserve shows what can be achieved through protection and community support. Although there are many other places around Sydney that have marine debris issues, we can all play our part by making informed decisions as consumers. As a community we can do more to protect these beautiful areas by ensuring that we respect our often-overlooked underwater neighbours.

Justin Gilligan is a freelance photojournalist with an honours degree in marine science. He has worked on numerous projects with Australia’s Commonwealth and State Fisheries Agencies. Several of Justin’s images have also received international acclaim in prestigious international photography competitions; he is a finalist in Wildlife Photographer of the Year 55. For further information, see justingilligan.com.

During the museum’s temporary closure to the public, much has still been going on behind the scenes, including planning for an innovative international exhibition about migration.

WE HOPE THAT YOU ARE ALL STAYING SAFE AND WELL.

While the museum has been closed to the public, we have been taking this opportunity to phone our Members and reconnect with them. What we have learned is that you all love Signals, so we hope you enjoy this latest issue of your magazine.

A new project is afoot

As the end of the financial year approaches, we are excited to launch our tax-time appeal to support the museum’s Migration Heritage Fund.

Australia has one of the most culturally diverse populations in the world and our multicultural society is a vital part of our collective Australian identity. Since 1945, nearly eight million migrants have stepped ashore to infuse modern Australia with more than 200 different cultural and linguistic traditions.

One exciting new project is A Mile in My Shoes. In collaboration with the Empathy Museum (UK), it involves a mobile giant ‘shoe shop’ that houses a diverse collection of shoes and audio stories exploring our shared humanity. Visitors are invited to walk in someone else’s shoes – literally. Visitors borrow a pair of shoes and walk a mile in them while listening to an audio recording of their owner’s life story – and so being taken on both an empathetic and a physical journey.

A Mile in My Shoes has already proved popular in 30 locations throughout the world. One visitor named Cecile noted:

Such a great idea and so effective to steep your mind in someone else’s reality. The sound is so good, it’s as though the person is talking into your ear, confiding … I listened to a story of loss and resilience told in Victoria’s clear and poised voice – heartbreaking and inspiring. Many thanks for this one-off experience.

The Australian National Maritime Museum is a great match for this project, being a hub for telling migration stories through our Welcome Wall (onsite and online), Passengers Gallery, rooftop projections, touring exhibitions such as On Their Own – Britain’s Child Migrants and upcoming free exhibitions Faces of Australia and Migrant Belongings

We are also more than a museum – we create encounters and experiences that change people’s understanding of Australia. The museum is responsible for collecting and exhibiting the national migration story, to build social inclusion and community harmony and help combat racism, which is why projects such as A Mile in My Shoes are so important.

To support A Mile in My Shoes through the Migration Heritage Fund, please complete and return the slip included in this edition of Signals or go to sea.museum/migration-fund

Direct deposits to the museum can be made to BSB 062 000

Account number 1616 9309

For more details please contact Marisa Chilcott, Foundation Manager, at marisa.chilcott@sea.museum or phone 02 9298 3619. Marisa Chilcott Foundation Manager

Our calls to Members have also prompted some wonderful stories, two of which we would like to share with you.

Susan Tomkins has been a member since January 1992: I first thought of joining the Maritime Museum because I loved sailing and had always had an interest in early voyages to Australia.

I then thought there might be a business opportunity as well. I owned an antiquarian bookshop in Paddington in Sydney so approached the museum to find they were building up their collection of books after opening in 1990. I had at that time a few diaries and journals of early migrant trips to Australia in the 1880s. And yes they were interested.

I also dealt in maps and engravings, particularly specialising in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands as well as Australia, so this also helped to build up their collection.

Over the years I have visited the museum many times. I particularly like the section on migrant stories – some of them so poignant and sad, others full of hope for a new life in Australia. The special exhibitions are also always fascinating, so I can’t wait for the museum to open again.

We wish to thank our generous donors who have supported the restoration of the Orontes model. This painstaking work continues, and we look forward to welcoming all supporting donors to the museum to observe the model’s progress and see first-hand how their donations have been used.

Keith Owen has been a member since 2002:

I was first acquainted with the museum when based in Sydney as State Director of the then Immigration Department in the early 1990s. I met Kevin Fewster (then Director), who was very keen to link the migration story to the activities of the museum. I used to hold a number of official functions at the museum – such a wonderful venue. One gathering was to promote citizenship. The guest speaker was Kay Cottee, then the Chair of the museum. She spoke about what it meant to her being an Australian when she sailed up Sydney Harbour at the end of her circumnavigation on her yacht Blackmores First Lady Well, there wasn’t a dry eye in the audience (including me!)

I retired from the Department in late 1990 and Kevin invited me to be a consultant to the museum to establish the Welcome Wall. The story went like this. The museum had to build a boundary wall due to the construction of a ferry wharf to service the casino nearby. He saw it as a great opportunity to showcase the museum to the passing traffic, otherwise it ran the risk of being just another wall covered in graffiti. He had visited Ellis Island near New York, where migrants to the USA were processed. There he saw a memorial with migrant names inscribed. Why not turn the museum’s boundary fence into a celebration of Australian migration?

But there was a difference. The names on Ellis Island were inscribed in alphabetical order. This meant that when you got to Z you couldn’t go back and insert more names. We decided to list names as received and let the Welcome Wall grow. We also thought that the random nature of the listing of the names would portray the richness of multicultural Australia.

My wife and I are now in Townsville, having lived for 20 years aboard our yacht. But each year, we visit Sydney and the Maritime Museum, which is high on our to-do list. We walk along the boardwalk and I see the Tu-Do and I recall receiving such refugee boats in Darwin. Then on to the Welcome Wall. It continues to grow and I feel very proud to have been part of the project.

We thank Susan and Keith for sharing their stories with us. If you have any stories you would like to share, please send them to me at oliver.isaacs@sea.museum

Oliver Isaacs Manager, Members Museum member Susan Tomkins. Image courtesy

The Australian National Maritime Museum Foundation

COVID-19 has triggered dramatic changes in the operations of the Australian National Maritime Museum and many longstanding plans have had to be adjusted or shelved.

With the loss of up to $10M in self-generated revenue, roughly a third of our budget, the museum is looking to the Australian National Maritime Museum Foundation – and its donors – for extra help next financial year.

A recent study found that most museum-goers are unaware that museums are facing challenges due to COVID-19.1 Yet, when asked how they felt the loss of museums would affect them, either through closures or dramatically reduced services, most said they would be devastated:

Our museums help keep our collective memory alive. If we lost even one of these important institutions, it would be like someone had blown out a candle or turned out the lights on a vital piece of our society.

A huge blow to children’s education. These trips help spark curiosity.

Without these organisations telling the stories of marginalised communities, many of those stories won’t be widely shared at all.

The Foundation is requesting donations to:

• Acquire important objects for the National Maritime Collection

• Support a major new exhibition

• Support the conservation of precious objects

• Assist the museum with strategic projects such as the search for Cook’s Endeavour

Your tax-deductible donation will help with the museum’s recovery from COVID-19.

We are not alone and we know many other organisations are facing similar shortfalls and we greatly appreciate your support at this time.

For more information go to sea.museum/donate or contact

Foundation Manager Marisa Chilcott on 02 9298 3619 or email marisa.chilcott@sea.museum

Sailors plying Tasmania’s Derwent River or people on ships visiting Hobart might be surprised to hear that beneath their bows, installations of ceramic spawning habitat support a rare and charismatic fish. Jane Bamford and Dr Tim Lynch explain their roles in helping to save this endangered species.

Egg masses were observed over time and eggs successfully reached maturity in the field on the ceramic ASH

THE SPOTTED HANDFISH (Brachionichthys hirsutus) only exists in 12 sites in the Derwent River and surrounding coastal waterways. It was the first marine fish to be listed as critically endangered on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s Red List. Unlike many fish that spawn into the water column and let their progeny travel on the ocean currents as plankton, the spotted handfish spawns on habitats attached to the sea floor and, curiously, guards its egg mass for six to eight weeks until each egg hatches as a fully formed tiny fish.

The spotted and other handfish were first collected by François Péron in 1802 when he travelled to Tasmania on Nicolas Baudin’s scientific expedition. They obviously made quite an impression, as Baudin himself made note of this distinctive fish in his journal: ‘Amongst the fish, there is a little one which is rather unusual in that its foremost fins are exactly like hands, and that it uses them for clinging to rocks when it is out of water’. The River Derwent in the 1800s was a very different waterway from today. At the time of Baudin’s expedition, its pristine waters were traversed only by Aboriginal canoes. European settlement saw a massive increase in boat traffic, from the original convict ships, whalers and vessels plying their trade and transporting goods, to today’s cargo ships, cruise ships and yachts. This increase in boat traffic and the growing human population have had numerous effects on the health of the river – including a large (but now collapsed) scallop dredge fishery, heavy metal sediments, run-off, pollution and, as in all ports, the introduction of invasive species. In addition, anchorages have altered the condition of the seabed and affected the quality of the water. All of these factors have changed the spawning habitat of the once locally common spotted handfish, catapulting it into the category of critically endangered.

Currently the spotted handfish’s battle for survival relies partially on production and deployment of artificial spawning habitats (ASH), which replace the natural spawning habitat provided by stalked ascidians (Sycosoa pulchra). This beautiful marine invertebrate has also been almost wiped out locally as a result of grazing from the invasive northern Pacific seastar, which was introduced into the Derwent River in the late 1980s, probably through the discharged ballast waters of Japanese bulk carriers as they collected their cargo of woodchips. Since the late 1990s, the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) had been using artificial spawning habitats, initially small plastic sticks, to provide somewhere for the fish to spawn. While effective, these plastic ASH are a form of pollution and are easily displaced by fouling or being dug up by various animals on the seafloor.

In an effort to continue to support spawning, Dr Tim Lynch, senior research scientist at the CSIRO, and Jane Bamford, a Tasmanian ceramist, began to work together with the CSIRO’s spotted handfish team to design and produce a ceramic ASH option. This collaboration drew on a design process inherent to both science and art, as well as the expertise of other individuals from a wide range of backgrounds – technicians, scuba divers, PhD and Masters students, yachties, engineers and marine scientists – reflecting the team’s diversity of interests, as well as the colourful history of the Derwent River.

Consideration of scientific protocol determined that major features of the first design of ASH remained constant, while changing the material from plastic to ceramic. This enabled the CSIRO to test how the fish accepted the new material, while controlling for all other factors. Clay was chosen as a potential material due to its composition of natural materials, the stability of these materials in seawater and, once fired in a kiln to 1280°C, its latent biosecurity. Any ceramics that broke in the dynamic marine environment would result in something similar to an inert tumbled pebble over time, unlike plastics, which eventually break down into micro-plastic pollution that absorbs dangerous chemicals, which can enter the food chain in the river. Jane selected Southern Ice porcelain for its high durability and its white colour to match the hue of the stalked ascidian. It is a filter-pressed clay, which reduces the presence of mineral salts that might affect the ASH’s safety for the handfish to spawn on.

Since the late 1990s, the CSIRO had been using artificial spawning habitats, initially small plastic sticks, to provide somewhere for the spotted handfish to spawn

01 Each handfish has a unique pattern of stripes and spots, enabling individuals to be identified. Image Laura Smith

02

A wild adult handfish on a diver’s glove. Spotted handfish are small, growing to a maximum size of only 12 centimetres. Image CSIRO

Initially, Jane created ceramic ASH for the CSIRO tanks, intended for the captive breeding program in aquariums, which forms an insurance policy should numbers further decline. These ASH were designed and made with a stem – the potential spawning area for the female to attach her eggs – and, for stability, a small coil stand to be buried in the thin layer of sand present in the tanks.

The spotted handfish mating dance was witnessed in captivity for the first time in 2017. This gorgeous spectacle astonished the onlookers as a gravid female, with her fins extended like sails, circled the base of an ascidian, attaching and depositing her egg mass from her swollen belly. With heightened attentiveness she was tailed by a slightly smaller male, fertilising her abundant small clear egg sacs with his milt. The pair was known to the Hobart community as Harley and Rose.

In September 2017, a gravid female spawned around a ceramic ASH at Seahorse World in Beauty Point, northern Tasmania, in what is believed to be a world first. The eggs developed naturally, with spotted handfish young hatching and surviving at rates similar to those in natural habitats. This was very exciting, as it was the first sign that there could be success with ceramic ASH in wild populations, and that it might be possible to reverse the declining numbers of this critically endangered marine species.

The

spotted handfish mating dance was witnessed in captivity for the first time in 2017

In 2018, the CSIRO commissioned Jane to make 3,000 ceramic ASH for use in that season. The two components of ceramic ASH were designed and made to accommodate a shrinkage rate of 14–16 per cent when kiln-fired. Each upright was hand rolled to compress the clay and ensure it remained straight once fired. One end was gently tapered to fit neatly through the diameter of the hole in the disc, to assist with construction before each scuba deployment. The purpose of the disc was to add stability to the ASH in the river substrate. It was important to make the ASH easy to handle under water, as divers would work for long hours with thick gloves on in the late winter water temperatures off Hobart of 9 –11°C. A dedicated deployment system was devised by the CSIRO for divers to carry the ceramic ASH on the boats and assist in handling them under water while minimising breakage.

In June 2018, five sites were randomly selected and ASH planted along transects where the densest populations of spotted handfish had been observed in the past. Divers reported finding the ceramics easier to deploy than the plastics, as they are negatively buoyant. Astonishingly, the newly planted ASH had immediate interest from the spotted handfish, which was a very exciting and encouraging sign, and in September 2018 came the first report of egg masses on the ceramic ASH, brought by Alex Hormann, a University of Tasmania (UTAS) Masters student studying spotted handfish behaviour. Alex, Tim and CSIRO divers continued to dive on all the sites and collect data on spawning on both ceramic and plastic ASH, as well as on natural ascidian spawning habitat. Findings showed that the spotted handfish prefer to spawn on the natural ascidians, where present, but once ascidian numbers decline below a critical density they switch to the ceramic ASH. Most importantly, the fish preferred the ceramic to the plastic ASH that had been planted as controls, using the ceramics for breeding at nearly twice the rate of plastic. Egg masses were observed over time and eggs successfully reached maturity in the field on the ceramic ASH after the six-to-eight-week period that the female cared for them.

Astonishingly, the newly planted ceramic ASH had immediate interest from the spotted handfish, which was a very exciting and encouraging sign

The ceramic ASH part of the project was recognised in late 2019 by winning the ‘Design for Impact’ category in the Design Tasmania Awards

Ceramic ASH had a higher rate of losses than the plastic ASH, probably due to large skates and rays landing on the ASH arrays and snapping them off at the base. To try to improve durability, the ASH stems were increased in diameter. In January 2019, five new diameters of ceramic stems were stress tested with the assistance of Dr Assad Taoum and his team at UTAS Engineering. On the advice of Dr Taoum, the disc component – an obvious weak point – was removed, and Jane made the ASH longer. No one knew if the spotted handfish would use the largerdiameter stems, and observation from divers in the field was critical to the decision. From this, two larger-diameter ASH, of 9 and 11 millimetres, were chosen to be hand made for the 2019 breeding season deployments to replace the original ASH stem size of 7 millimetres.

Our initial results from 2019 suggest that durability has increased dramatically, with losses down from 37 per cent to as little as 3 per cent, which is even better than the 8 per cent loss rate of the plastic ASH. The new design also allows for very easy cleaning. The longer ceramic ASH can be pulled out of sediments; the exposed top section is easily cleaned with dive gloves and the already clean, previously buried section then provides a clear, white surface for the next round of spawning. CSIRO divers counted stalked ascidians earlier in the year and then targeted ceramic ASH planting only where needed. With the much-improved durability and ease of cleaning, these new ceramic ASH arrays have the potential to last over the longer term. This has improved the viability of the conservation project by keeping down the cost of ASH production, deployment and maintenance. The ceramic ASH part of the project was recognised in late 2019 by winning the ‘Design for Impact’ category in the Design Tasmania Awards.

The Derwent River contains many small bays and safe anchorages, offering protection to yachts from the prevailing winds and locations where they can have permanent moorings. The spotted handfish also inhabit these bays, and unfortunately every time the wind changes direction, the heavy chain used to moor a vessel is dragged along the seabed, destroying the fish’s habitat. To conserve handfish habitat, Lincoln Wong, a PhD student at the University of Tasmania and the CSIRO, is working on trialling and implementing environmentally sustainable moorings with citizen scientist volunteers.

01 Jane Bamford with two of the original-design ceramic ASH. Image Uffe Schultz

02

The female spotted handfish guards her eggs for six to eight weeks, until they hatch as tiny, fully formed fish. Image Alex Hormann

These new moorings, designed by CSIRO engineers, replace the damaging heavy chain with a rubberised strop and dramatically reduce the impact of the mooring on the seafloor, with attendant benefits not only for the spotted handfish populations but for all biodiversity in these shallow waters. It is very exciting to think that this initiative, which can help conserve spotted handfish habitat, may also have a more widespread positive legacy in reducing the damage caused by moorings all around the world’s coastlines.

The impact of ceramic ASH design and production will further protect the spotted handfish from extinction, stabilise existing populations and allow for recovery.

More generally, it demonstrates a successful synergistic collaboration between art/design and science. The many similarities between these two fields – the development of practice, iteration, repetition, design, experimentation, craft, observation and measurement – have merged seamlessly. In many ways the work is also a performance by the divers, the artist and the spawning spotted handfish, which are an icon of the Derwent River. Using one of our most ancient technologies, ceramics, and creating a beautiful and tactile handmade small-scale production object, the project invites us to imagine this unseen underwater spawning performance. Furthermore, this encourages us to consider broader perspectives of the anthropogenic epoch and beyond. Is it possible for the River Derwent to return to somewhere near the condition in which the sailors and naturalists of Baudin’s expedition found it? As we consider how science, creativity and design processes can actively work in collaboration to avert the spotted handfish’s extinction, we might also contemplate how an innovative and collaborative approach might assist many species presently falling into the Earth’s sixth mass extinction.

The spotted handfish project has been truly a community undertaking, with some of the key supporting partners being National Handfish Recovery Team, UTAS Centre for the Creative Arts, UTAS Engineering, NRM South, Derwent Estuary Project, Sea Life Melbourne Aquarium, Marine Solutions, Reef Life Survey (Tas), Marine Biodiversity Hub, Department of Environment (Commonwealth), National Environmental Science Program, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (Tas), Seahorse World, Clayworks Australia, Marine Life Tassie and Marine and Safety Tasmania. The project is part the larger handfish conservation project handfish.org.au/ For more information on Jane Bamford’s work, see @janebamford_ceramics on Instagram or visit janebamford.com

All

Cruise passengers in a Zodiac get a close look at the Garibaldi Glacier, Patagonia.

Cruise passengers in a Zodiac get a close look at the Garibaldi Glacier, Patagonia.

At 8.30 am on Wednesday 18 March, a LATAM 787 trundled down the regional airstrip at Puerto Montt in Chile at the start of what was probably the first trans-Pacific flight from this location. Although the plane’s capacity was more than 250, the only passengers were 16 Australians. The flight was the culmination of several days of boredom, frustration and high drama for most of the 150 or so passengers on the cruise ship Silver Explorer, as the COVID-19 pandemic began to bite in Chile. By Michael Waterhouse .

The cruise started uneventfully at Ushuaia, Argentina, on Wednesday 4 March, though against the background of growing global concern about the spread of the coronavirus COVID-19. All embarking passengers, including my wife Vashti and myself, had their temperature taken in Buenos Aires before flying to Ushuaia, with no one exhibiting any symptoms. Perhaps naively, we also took comfort from being at the other end of the world from China, the apparent epicentre of the virus.

The following few days were idyllic, the ship gliding gracefully back and forth through spectacular fjords, with Zodiac excursions to see glaciers and wildlife at close quarters. Nature at its most pristine.

The first township we encountered (Saturday 7 March) was Punta Arenas, its central tree-lined square dominated by a massive 19th-century statue of Ferdinand Magellan. This had been spray painted by demonstrators, and though cleaned, the residue was still evident. As the person who first opened up the area, Magellan is reviled by many as the man whose discoveries led eventually to the decimation of local indigenous tribes.

The museum, in a house once owned by a wealthy colonist (and so an oppressor of local tribes) had also been similarly defaced. Here and there on the walls of buildings, painted graffiti such as ‘Rebelion Popular!’ hinted at the potentially fragile nature of Chilean democracy.

We moved on up the coast of Patagonia, through more exhilarating fjords thick with ice floes, until we arrived at Puerto Natales (Monday 9 March) – the jumping-off point for Torres del Paine National Park. The scenery in the park was quite extraordinary and we’d been given enough geological information to make sense of it all.

Thursday 12 March: Next port of call was Tortel, a picturesque commune lining a fjord, with boardwalks winding irregularly around the waterfront. Back on board we were having lunch when the captain announced that a passenger who was suspected of having COVID-19 had been disembarked and flown to hospital.

Friday 13 March: A day at sea as we headed for Castro, with no idea of whether we would get ashore there – if the passenger tested positive, this would change everything. And so it proved. As we approached Castro on Saturday 14 March, news came that he had indeed tested positive and immediately after breakfast we were all asked to return to our cabins. This was day 1 of our confinement.

Fragments of emails which passed back and forth with our family in Australia convey a sense of how things played out.

Sunday 15 March (day 2): Vashti has a cold – blocked sinuses, runny nose and a slight headache. We thought it best to report this and did so this morning. However, although a Chilean medical team has been crawling all over the ship testing passengers, they haven’t been anywhere near us.

We haven’t been allowed out on deck for exercise and fresh air – we don’t have a balcony so no way of getting fresh air directly. Menus give us a limited choice from which to select breakfast, lunch and dinner. Food is of a high standard and you can request wine or beer. Its arrival is signified by a knock on the door and then you retrieve it once the masked crew member delivering it has gone.

Late this afternoon a flurry of activity, with the ship’s doctor ringing and a nurse visiting. Vashti’s temperature was up but within the ‘normal’ range. They’ve run out of swabs so will do this tomorrow morning.

Communication from the captain has been limited. We’re just sitting here, a few hundred metres out from shore (Castro, we think), with no idea of what’s happening.

(Later) As best I understand things, we’re officially in quarantine and can only leave when the Chilean government says so. Advice from the expedition leader Danny is that the US may deny us entry, and I guess this means others (Peru, Ecuador, Canada) may do likewise.

We see no-one, talk to few (by phone), watch films (good selection). As Vashti says, it’s amazing we’re still speaking to each other. Two days now without permission to step outside on deck, even when we’re right out at sea. We’re OK, really. Just frustrated at being confined to a 10 x 3.5 metre ‘prison’ (albeit one with excellent food) when people could easily be walking around the deck keeping a couple of metres apart. Apparently ‘protocols’ don’t permit this.

Cabin 323We see no-one, talk to few (by phone), watch films (good selection). As Vashti says, it’s amazing we’re still speaking to each other

Four passengers and one crew had been disembarked in Castro as they had shown some coronavirus symptoms

From our daughter (a doctor) in Sydney: The main thing to watch for is becoming breathless. As long as it is a blocked nose, cough, fever etc it’s probably staying in the upper respiratory tract (which is good) whereas breathlessness indicates it’s moved lower and this is more of an issue. If this happens, insist that they test you with a pulse oximeter (clip on finger that tells the oxygen in your blood).

Monday 16 March (day 3): Reception rang 10 minutes ago – at 4.10 am!!! – to say that Vashti had to be ready at 7 am for them to take her ashore in a Zodiac – probably a 10-minute ride – so she could be tested for coronavirus. Once I was fully awake and we’d had a chance to discuss it, I rang back and said this wasn’t going to happen, that Chilean officials had the whole day yesterday to check her but hadn’t, and that when a nurse checked her late in the day, her temperature and blood oxygen levels were within the normal range.

Initially, I understood that Vashti would just be going ashore for a swab, not realising that in fact she’d been asked to pack her suitcase. This was to be a permanent departure from the ship, though with no explanation given as to why it was necessary or where she’d be going. All we were being told was that she’d be going ashore. There was briefly a suggestion that I might accompany her on the helicopter, but they then equivocated as to whether there’d be room.

The risk of her being stuck in a regional hospital at Puerto Montt (near Castro) while the ship sailed away to God-only-knowswhere and then trying to sort out how to get back together again was just too great when there was no compelling medical reason for her to go. A little surprisingly, the Chilean health authorities didn’t press it. There was a flurry of increasingly impatient calls from reception and I was ready for guys with guns at the cabin door. If they were genuinely concerned, I’ve no doubt they would have forced the issue.

Vashti, in an email to our children in Australia: Didn’t appreciate being woken at 4 am and told to be packed and ready to go ashore at 7. But Michael took on the hotel lobby manager and the ship’s doctor and said he didn’t care what the Minister of Health said, I wasn’t going ashore. He even locked the cabin door but I daresay they would have beaten it down if they’d thought me really contagious. Those being disembarked were to be sent off in a helicopter and as M said, sitting with possibly contagious people in this would be risky.

(Later) At about 8.30 am the captain advised us that we would be moving off out to sea, though to an unknown destination. He said four passengers and one crew had been disembarked in Castro as they had shown some coronavirus symptoms.

We then sailed round and round in circles and are now headed back into Castro again. A few passengers, including ourselves, were given a chance to go up on deck, but asked not to tell others. Suitably rugged up, masked and gloved, and escorted by a crew member, we got 15 minutes to walk around the ship. It was terrific!

What happens when we get back to Castro is anyone’s guess, though I’ve just noticed we’re going out to sea again so it’s obviously not going to be for a while yet. I think cruise ships everywhere are being turned away and so we may end up like the Flying Dutchman, travelling round the world in perpetuity! Have just been asked for our requirements for medicines for the next 14 days. Not a good sign. I think it’s going to be a while before we get home!

Advice from Sydney: Silver Explorer is anchored off Puerto Montt. The locals do not want it to dock and let anyone off. Chile will agree to the ship docking only if countries with nationals on board each agree to repatriate their citizens –which means they have to arrange charter flights all the way home, not just accept you if you make your own way there.

01 Vashti and Michael at Torres del Paine National Park.

Tuesday 17 March (day 4), about 9 am: Captain’s just advised us to pack our suitcases as we could be leaving the ship at short notice. He asked us not to put anything out on social media. Two cabins nearby have yellow square stickers on them –presumably someone inside in quarantine. Modern equivalent to a red cross on the door in the Middle Ages when someone inside had plague!

Vashti: Having been kept in the dark so long it was a eureka moment when the captain came on this morning and actually SAID something. Up till now he’s been telling us nothing.

(Mid-morning): It looks like we will disembark in the next couple of hours. One of the crew told me we’d be going to another country, not Santiago. I had the impression that it will be a charter flight directly to Australia from Puerto Montt. If correct, we’ll be on our way this evening and back home tomorrow.

We continue to move aimlessly back and forth, our movements being closely monitored by a Chilean patrol vessel. Are they worried we’ll make a dash for the shore? No further announcements. Suitcases packed.

Lunch and now dinner have come and gone. Quality of food has declined, but it’s amazing they’ve been able to give us what they have, and even a choice.

(Later) From our daughter: I am told your flight will depart Puerto Montt @ 9am Chile time and arrive in Sydney @ 7.15pm Sydney time.

(11 pm): Announcement that passengers will be disembarking by Zodiac, beginning immediately, with people to be called by cabin number. Those suspected of having coronavirus to remain behind, their partners free to stay or leave. No indication about where we are to go.

Vashti and I were called in about the sixth group, about 11.30 pm. Temperature check: Pass. Mandatory face masks and disposable gloves on. Down the steps onto the Zodiac flopping back and forth, the glare of lights accentuating the inky blackness enveloping the ship. It was quickly apparent we were heading for a large car/bus ferry about 400 metres distant.

Our Zodiac pulled up onto a ramp at the rear of the ferry, quite unstable in the choppy water. Narrowly avoided a wet landing as we clambered out as best we could, assisted by men and women in gowns and masks, with several policemen nearby watching. No masks but pistols clearly visible.

Once on the ferry, and after a mad scramble for some carry-on bags we nearly left on the Zodiac, we were quickly hustled onto onboard buses, with instructions to sit separately – one person per two seats. There were six buses with perhaps 120–130 people. When everyone was in a bus, the ferry set off on what were told would be a 50-minute journey – destination unknown. In fact, it was more than 1½ hours before we pulled into what appeared to be a dimly lit industrial port a bit after 2 am (Wednesday 18 March).

Here were more police standing around, guns clearly visible, watching as the buses disembarked. A cameraman was running around filming in the dim light. Police were also filming on their phones.

The last bus finally ashore, we set off in a convoy – escorted by police cars with flashing lights – on a 40-minute ride along what appeared to be a series of back roads with the occasional house but mostly bushes and long grass. We assumed we were heading for an airport but still no word on where we’d be flying.

If Chile hadn’t taken the hardline stance it appears to have done, perhaps we’d be among the many Australians who were stranded in South America or on cruise ships long after we returned

Eventually around 3 am an airport emerged through the gloom, dim lights shining through fog, a large plane standing silently nearby. It was extremely cold, perhaps three degrees, as we were hustled into a terminal that was still under construction, and sealed off by glass from the rest of the building.

Given the secretive and impersonal nature of the process thus far, it was nice that someone, realising how cold it would be inside the terminal, had put out a blanket on each seat and a pack containing drinks and nibbles. I assumed we had Silversea to thank for this, as the Chilean government’s haste to get rid of us didn’t suggest they were into nice gestures.

After a certain amount of confusion, it was eventually explained to us that there would be three flights – one to Miami for the Americans, one to Sao Paulo and thence to London for British and Europeans and one back to Sydney for the 16 Australians. However, our suitcases had been left on board – Silversea later explained to us that ‘the Chile government would not allow the luggage to be transferred to your flight home’.

The Americans left almost immediately. Eventually, at about 5 am, the British and Europeans and ourselves split into two groups and left the terminal in our respective buses. We sat in ours near a LATAM 787 for what seemed like another hour before the 16 of us were allowed on. Eventually we took off at 8.30 am, almost 24 hours after we were first told to get ready to disembark. The flight was about 14 hours, skirting Antarctica and arriving in Sydney at 11.40 am on Thursday. More temperature checks, through passport control, into a car provided by Silversea, and then home. Exhausted, but home and into isolation.

For the first few days we were both exhausted. Vashti described it as the worst jet lag ever. Our daughter prevailed upon us to be tested for COVID-19 and later that day we were advised we’d both tested positive.

About a week later I developed a cough and as it became more severe, I was admitted overnight to St Vincent’s Hospital for tests. An X-ray and CT scan revealed that I had bronchopneumonia. With the benefit of antibiotics it cleared gradually, with no lasting effects. This and the extreme tiredness were the worst of our experience with COVID-19. Given what others have been through and the deaths of a number of people of about our age, we can only consider ourselves extremely fortunate.

As we convalesce at home, we’ve reflected on how differently this could all have played out. In all likelihood, had Vashti been tested on the ship in Chile – and it was only because they ran out of swabs that she wasn’t – she would have been positive.

In retrospect, our decision for Vashti not to leave the ship proved critical. Had she simply gone along with their request, as she was inclined to do as she wasn’t feeling well, she’d still be in Chile, in a hospital somewhere or perhaps discharged into some other accommodation.

It was evident from everything we heard and which occurred while we were on Silver Explorer that the Chilean government was single-minded in its efforts to ensure that those on the cruise ship did not infect the local population (a view soon adopted by many other countries, including Australia) and that the issue be resolved as quickly and as quietly as possible. Perhaps the ‘Rebelion Popular!’ graffiti in Punta Arenas highlights why the government may have been particularly sensitive to the mood of its nationals.

After we returned, I assumed that the Australian government had paid for our flight. Not so. It transpires that Silversea paid LATAM what must have been a considerable amount to fly us back to Australia.

Ironically, if Chile hadn’t taken the hardline stance it appears to have done, perhaps we’d be among the many Australians who were stranded in South America or on cruise ships long after we returned.

So the stars aligned for both Vashti and me when the outcome could so easily have been far worse. Watching TV footage of others on cruise ships, confined to their cabins and retrieving food left outside their doors, remains a discomfiting leitmotif.

Michael Waterhouse is an economist and historian.

His book Not a Poor Man’s Field. The New Guinea Goldfields 1942 – An Australian Colonial History was published in 2010. Vashti Farrer is an award-winning author.

Have you been on a cruise ship recently? Tell us your story

Cruise liners form an integral part of the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

Were you a passenger, crew member or responder on any of the cruise ships caught up in the recent public health crisis?

The Australian National Maritime Museum would love to hear from you about this important moment in our national maritime history. Memories, photographs, artefacts and memorabilia will help us tell this story. Please contact curator@sea.museum with your email or phone number and we will get back to you.

For more details go to sea.museum/covid-stories

The museum’s teams have been busy developing innovative ways to continue sharing Australia’s stories of the sea

On 24 March, the museum temporarily closed its doors as a response to the COVID-19 global pandemic. It is now preparing to reopen and welcome visitors once more.

AS SIGNALS GOES TO PRINT, the museum plans to re-open its doors on 22 June to visitors in a limited capacity. We are working through the arrangements to ensure the safe operation for both patrons and staff. These will include increased cleaning, distancing procedures, online bookings, timed visits and allocated times for vulnerable sectors of the community.

We are greatly disappointed that, due to the social distancing measures, some events – such as the popular Classic and Wooden Boat Festival – could not go ahead this year.

Sadly, we were also unable to proceed with the voyage of the HMB Endeavour replica around Australia or the accompanying travelling exhibition Looking Back, Looking Forward, designed to mark the 250th anniversary of James Cook’s charting of the east coast of Australia.

However, the museum has developed a wide range of online content to commemorate this event, which you can read about on pages 47–48.

With Australians staying at home and bans on international visitors, the museum’s teams were busy developing innovative ways to continue sharing Australia’s stories of the sea. We’ve created a virtual museum at sea.museum/ so you can explore many of our exhibitions, collections, vessel tours and library resources online. We’ve also created new digital offerings, such as games, behind-the scenes videos, past editions of Signals and a virtual edition of our popular Ocean Talks series. You can read more about these online talks on page 44.

Work continues on site to ready the museum to again receive visitors. We are installing a new permanent exhibition, Under Southern Skies (see page 46), which can be seen in person once the museum reopens. Online exhibitions currently available are Elysium Arctic, Sea Monsters, War Brides, Wildlife Photographer of the Year, Undiscovered: Photographs by Michael Cook, Waves of Migration, Sea of Rainbow, On Their Own: Britain’s child migrants, and War and Peace in the Pacific 75 For more information on these online exhibitions, as well as onsite exhibitions planned for once the museum reopens, please see pages 46–48.

Our Education team has created new online programs to support teachers, parents and students. They include content to create a deeper understanding of Cook’s voyage as part of the Encounters 2020 program and digital case studies in the museum’s key themes of migration and maritime archaeology.

There are also engaging videos for children, such as the lighthearted Pirate School with the museum’s resident pirate captain Grognose Johnny, plus plenty of kids’ activity sheets featuring puzzles and colouring activities, which can be downloaded and printed at home.

Please stay connected with the museum by following our Facebook page and visiting our website for our virtual content. We look forward to welcoming more back visitors to our Darling Harbour site in the coming months.

Michele Camilleri, Strategic Communications Manager

new permanent

For sailors, dancing on board ship had a long and established tradition and was a favourite entertainment

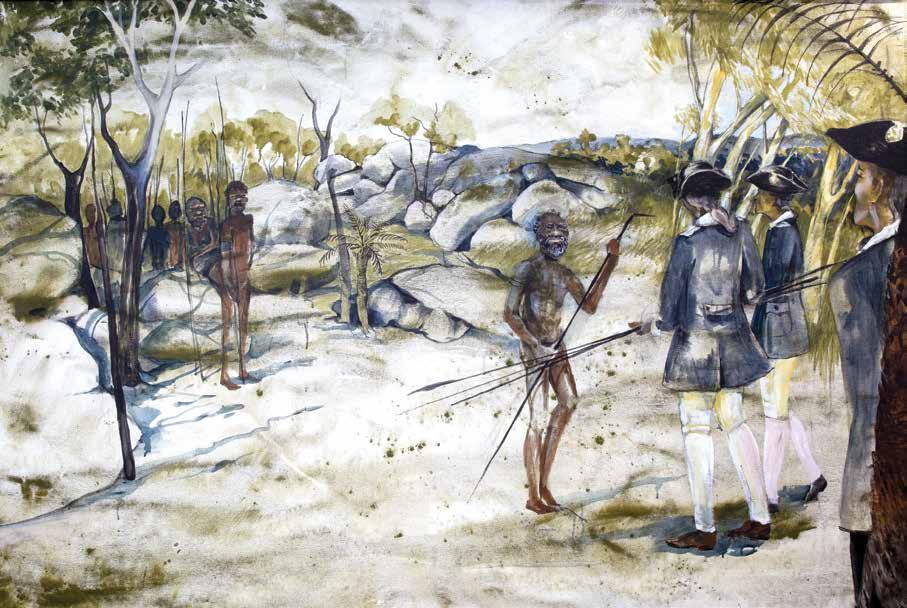

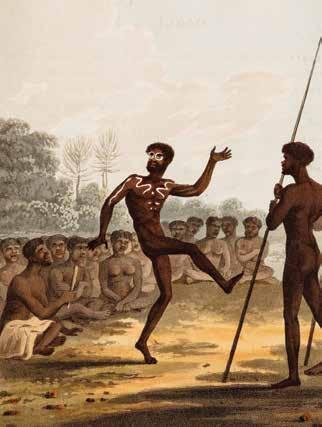

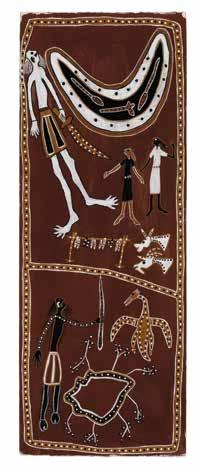

One perspective of James Cook that has rarely been examined is how music, theatre and dance were interwoven into his life and served to venerate him after death. He used music and dance to keep his crew healthy and to establish peaceful communications with people he encountered on his voyages, and his own life was commemorated in dance. By Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke .

Captain Cook wisely thought that dancing was of special use to sailors … it was to this practice that he mainly ascribed the sound health which his crew enjoyed 1

DURING THE 18TH CENTURY, the English were known as a nation of keen and accomplished dancers, from the king to the lowliest labourer. Indeed, it was one of the chief ways people entertained themselves. The English country dance was a highly social dance form; perhaps this accounts for its great popularity. Many new compositions were published each year to cater for the burgeoning demand, and their titles were inspired by current affairs of the world. Important events, famous people and significant places were all celebrated in music and dance. My research began with the discovery of The Transit of Venus in a collection of dances from 1775.2 This sparked an extensive study that traced Captain Cook’s life, achievements and death through the popular culture of the time.

and visiting women dance to a fiddler’s

deck

a ship. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection ID PAH7355

The enthusiasm for dancing in the Georgian era led to the building of so-called ‘assembly rooms’, constructed expressly for this purpose. It is fascinating to note that after his marriage, Cook chose a home for his young family next door to such a venue in Assembly Row, Mile End, east London – a place itself celebrated in the dance The Mile End Assembly. Assembly rooms were reserved for the upper and middle classes, while people lower down the social ladder danced in taverns. The English navigator William Dampier noted that his sailors learnt to dance in the ‘musick houses’ 3 in Wapping, the same dockside area in London where Cook’s in-laws kept the Bell Tavern.

For sailors, dancing on board ship had a long and established tradition and was a favourite entertainment. It was more than the drunken frolic that we in the 21st century might imagine; it was a skilful art requiring balance, co-ordination, strength and endurance. The best sailors were the topmen, who climbed high into the rigging and were regarded as the elite in the seamen’s hierarchy. They were also considered the best dancers.

Dancing was widely judged to have health-giving qualities, and Cook recognised these benefits and utilised them to good effect. According to the historian Carlo Blasis writing in 1830, Cook, ‘wishing to counteract disease on board his vessels as much as possible, took particular care, in calm weather, to make his sailors and marines dance to the sound of a violin, and it was to this practice that he mainly ascribed the sound health which his crew enjoyed during voyages of several years continuance.’ 4 Modern scientific research endorses dancing as one of the best forms of exercise, maintaining good physical, mental and emotional health, including as it does creative expression, co-ordination, musicality and social interaction.

On Cook’s voyages in the Pacific, the ability of sailors to dance added a positive and cheerful tone to encounters with Indigenous people. It was employed in cultural exchanges when Cook’s men danced hornpipes and country dances to entertain the islanders, in attempts to reciprocate their rituals of greeting. Music was provided by the ship’s musicians; on the Endeavour, the fiddler was Thomas Rossiter. On subsequent voyages the Admiralty arranged for a number of musicians to be part of the crew.

As Cook noted in August 1773 in Tahiti:5

When the king thought proper to depart, I carried him again to Oparree in my boat; where I entertained him and his people, with the bag-pipes (of which music they are very fond) and dancing by the seamen.

The president of the Royal Society, Lord Morton, issued ‘a list of hints’ to Cook and the gentlemen on the Endeavour. These hints include advice on how to approach the people they would meet – ‘not with the report of Guns, Drums, or even a trumpet ... but if there are other Instruments of Music on board they should be first entertained near the Shore with a soft Air’. The Admiralty supported this approach and on Cook’s second and third voyages organised a variety of instruments, including Highland bagpipes, French horns, hautboys (oboes), fifes and flutes. It was firmly believed music and dance helped to establish friendly contact, having the power to entertain, amuse and pacify: ‘I caused the Bagpipes and fife to be played and the Drum to be beat … this they admired most’, noted Cook in 1773 while in Dusky Bay, New Zealand.6

News of Cook’s travels and discoveries caused intense interest in Britain and throughout Europe. Before the era of film and television, it was difficult for people to visualise the places and people he had encountered. An important way to present the story of Cook’s voyages was through the theatre.

The first ballet to portray Cook was produced in Italy in 1784 and was titled Gl’inglesi in Othaiti (The English in Tahiti). It received dazzling reviews, was staged many times and was translated into German and Spanish.

The first English production was the pantomime Omai, or, A Trip Around The World. The title referred to the Tahitian man Omai, who had travelled to England with Cook in 1774 and achieved celebrity status before returning home two years later. The pantomime, staged in 1785 at the Covent Garden Theatre, London, was an immediate success – a blockbuster of the 18th century. The characters and scenery were drawn from the places Cook had visited, featuring authentic costumes, impressive stage designs and extraordinary special effects. The plot had little to do with Cook, but presented Omai as a Prince of Tahiti who fights the enchantress Oberea in order to regain his throne, before sailing for Britain to claim his bride ‘Londina’. A theatre critic from The Morning Chronicle wrote: 7

Every person who has read the history of Captain Cooke’s [sic] Adventures, should see the new pantomime Omai.

The manners of the natives in the new discovered islands being there pourtrayed [sic] to the life, and the soil, and culture of Otaheite, &c. picturesque beyond imagination, or what can be conveyed into the understanding by reading or plates.

01

Wapping by Thomas Rowlandson (1807) depicts a scene from a sailors’ tavern in London.

© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London ID PAF3823

02

Title page and dance instructions for Captain Cook’s country dance, published in London in 1797. Public domain

Assembly rooms were reserved for the upper and middle classes, while people lower down the social ladder danced in taverns

Following the great success of Omai, a new theatrical extravaganza was created, first in Paris, then in London: The Grand serious pantomimic ballet, The Death of Captain Cook 8 The story bore little resemblance to any actual event. It did, however, give an elaborate depiction of the people and places Cook had visited. The scene is set on ‘The Island of O-Why-e in the South Sea’ where the king of Hawaii is at war. Cook assists in defeating his enemies and although the ruler wishes to execute the prisoners, Cook saves them. Despite this he is attacked and murdered by the enemies, as they regard him as responsible for their defeat. The first performance evoked tears and hysterics when the audience saw the captain stabbed to death. This dramatic if fanciful representation of Cook’s death was an important factor in the ballet’s ongoing success and popularity throughout the British Isles, Europe and America. In the late 18th century it was common for plays, pantomimes and ballets to include dances that could be adapted for a social setting. The dance Omai was an example of this – it came directly from the pantomime and was published in Campbell’s 2nd Book of New and Favourite Country Dances (c1786). People across an increasingly industrialising Europe and North America were fascinated with Cook and with his travels in the exotic and remote Pacific region. We know of the numerous books and paintings created about the great navigator, but comparatively little about the number of dances created, such as Transit of Venus, South Seas, Island of Love, Trip to Ottahite (Tahiti), and Captain Cook’s Country Dance. It was in dance and song that people from all walks of life could venerate the great navigator.

1 Blasis, C, The code of Terpsichore. 1830, London: E. Bull.

2 Bride, Favourite Collection Of Two Hundred Country Dances 1775, London.

3 Dampier, W, A New Voyage Round The World. 1697, Printed for James Knapton ... London.

4 Blasis, op cit.

5 Cook, J, The three voyages of Captain James Cook around the world. 1821.

6 Cook, J, J C Beaglehole and S Hakluyt, The Journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery. 2, 2. 1969, Cambridge: Published for the Hakluyt Society at the University Press.

7 The Morning Chronicle. 1785 London.

8 The death of Captain Cook a grand serious-pantomimic-ballet, in three parts . 1789, London: Printed for T Cadell, in the Strand.

Dr Heather Blasdale Clarke is a dance teacher and historian specialising in early Australian colonial culture. She has carried out extensive research in this hitherto untouched area of social history, including doctoral research into the intriguing topic of convict dance 1788–1840. She has developed a free online resource: colonialdance.com.au/dancing-with-cook. A book and CD, Captain Cook’s Country Dances, have recently been released, as well as a unit for teachers aligned to the primary school curriculum; they can be purchased at the above website.

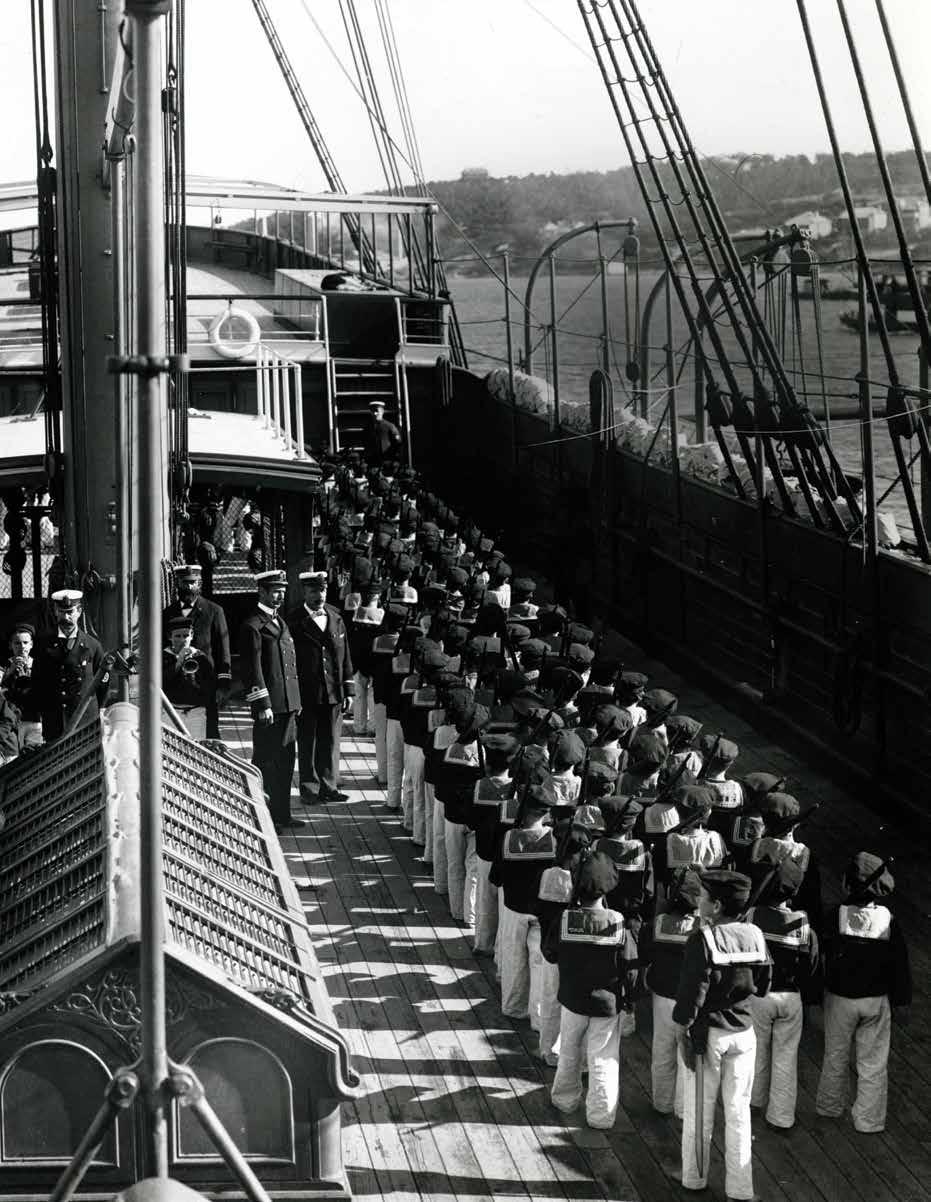

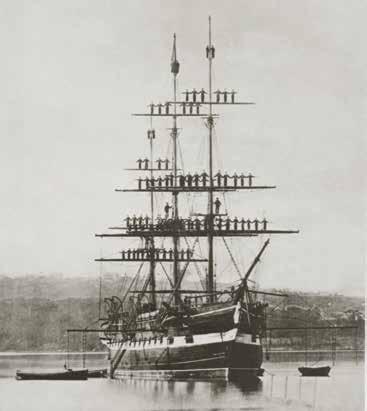

Boys performing drill aboard Sobraon ANMM Collection ANMS1096[205]

Boys performing drill aboard Sobraon ANMM Collection ANMS1096[205]

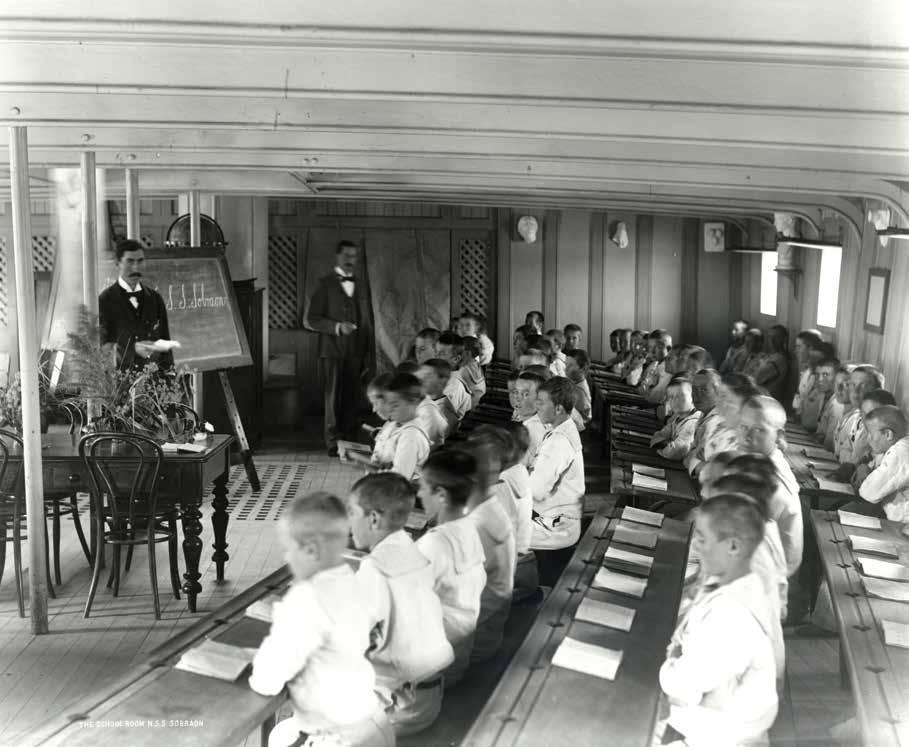

Delinquent boys, or ‘larrikins’, who were arrested and sent to Sydney’s Nautical School Ships Vernon and Sobraon between 1867 and 1911 were educated by an eccentric curriculum of academic lessons, trade-training and recreation, all designed to civilise them. Fascinating traces of these activities can be found today in items in the museum’s collection, writes Sarah Luke .

01 The manning of Vernon ’s yards –with the boys spidering up the masts in their neat sailor suits – was often the focus of photographic images of the era. ANMM Collection 00027245

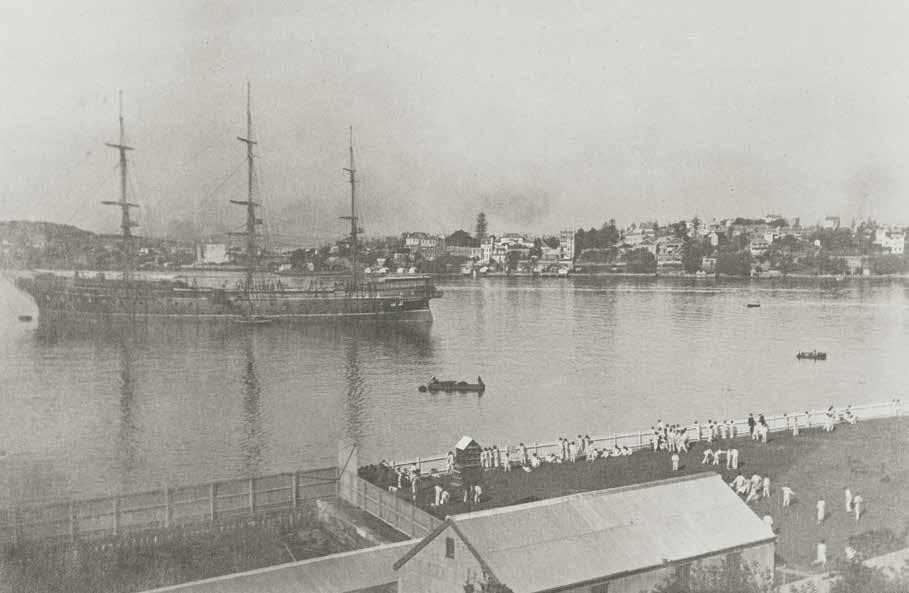

02 Recreation on Cockatoo Island, with the Sobraon anchored nearby. ANMM Collection ANMS0031[100]

One journalist from the time mused that visiting the Vernon was on many tourists’ lists of must-do activities

With the introduction of the Industrial Schools Act in 1866, being uncared for became a crime if you were a child or teenager

IN THE 1860S, SYDNEY’S WHARVES AND SLUMS were crawling with poor and neglected children. They spent their days shining the boots of the patrons of their parents’ ‘houses of ill fame’ (brothels), selling watercress and matches on the streets, and picking pockets. Some had homes – ramshackle houses devoid of furniture – and parents who were frequently drunk. Others were street orphans who were integral members of the city’s various gangs, or ‘pushes’. Some of these neglected youths might have had a little education – the well-meaning teachers at the Ragged Schools1 having managed to teach them the alphabet, at least – but most could not even write their own names.

In 1866 that all changed, with the introduction of the Industrial Schools Act . This legislation gave the police power to arrest children under 16 who had no job, who merely ‘wandered’ the streets, or who were being neglected by their parents. Being uncared for became a crime if you were a child or teenager.

To receive these boys, the state government purchased and fitted out a vessel, the Nautical School Ship Vernon, and anchored it permanently in Sydney Harbour. For some time the Vernon remained near Farm Cove (where the Sydney Opera House now stands), but by the early 1870s had found its permanent and famous home further west, beside Cockatoo Island. For the next few decades, Vernon ’s bugle-call frequently interrupted the working harbour as it signalled a change in the boys’ daily routine.

The floating institution quickly became an icon of the harbour. One journalist from the time mused that visiting the ship was on many tourists’ lists of must-do activities. 2 Bright purple tickets were issued to ladies and gentlemen keen to see the boys in the middle of their reformation from larrikins to useful, productive members of society. Visitors also revelled in dramatic militarystyle drill displays by the youthful cohort. Impressed visitors often sent treats to the ship – baskets of fruit, books and games.

Fresh sea air and strict naval-style discipline were what these boys were thought to need to catalyse their reformation. The Vernon had advantages in that escape was almost impossible should any boys desire to return to their old lives. It would require stealth to get into the water, and strength to survive the swim to shore – but the difficulty of escape also created in the public imagination the notion that the ship was akin to a juvenile prison hulk. This perception was – and still is today – difficult to shake off.

Naval-style discipline

Once brought on board, new recruits were installed into a strict routine. The boys’ days were divided between school, trade training – such as carpentry, sail-making, agriculture on Cockatoo Island, sailing and baking – and various types of recreation. After about a year on board, boys were then apprenticed somewhere in New South Wales until they were 18. On their 18th birthday they would be given the wages they had earned, with the intention that they could then look after themselves and find work in the trade in which they had been apprenticed.

It took some time for the ship’s order and routine to be established. The Vernon ’s early years were plagued by troubles: fighting between the staff – thanks to the inept first superintendent, Captain Mein – poor-quality food, and confusion about the purpose of the institution.

The first two teachers, in particular, were disastrous. The original one, Henry White, was arrested mid-lesson one day, charged with forgery. He consequently spent time in Darlinghurst Gaol, beside the parents of some of his former pupils. White’s replacement, John McSkimming, was cruel to the boys, often hitting them with rulers to wake them up after they fell asleep in his lessons. One day he went mad; described as a ‘dangerous lunatic’, he was taken to Gladesville Asylum.

Sobraon had a well-equipped gymnastic club and an impressive swimming club that turned out some champion athletes

Despite the perception that the ship was a prison rather than an industrial school, the Vernon continued to accept boys from all over New South Wales and was so well-populated that in 1892 it was replaced with the Sobraon, which was three times bigger. Immediately the numbers of boys began to swell. At peak capacity, in 1906, there were a staggering 425 boys. 3