Tasmanian Hydrowood

Operation

Tasmanian Hydrowood

Operation

WELCOME TO THE SUMMER EDITION of Signals, a summer celebrating exploration.

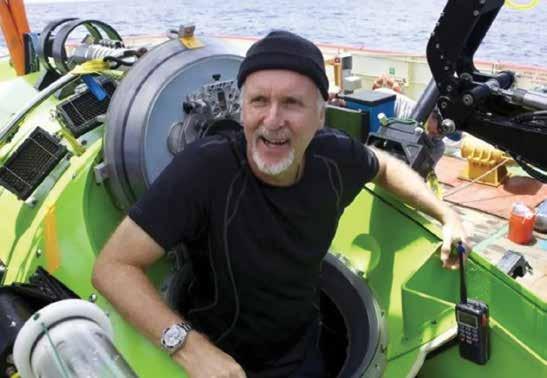

It’s been an exciting few months, with the return of James Cameron – Challenging the Deep delighting guests of all ages, the launch of our brand-new Chains of Empire and Inundated exhibitions, the unveiling of a new panel on the National Monument to Migration, and the longawaited launch of our revamped museum website.

We are thrilled to once again host the Ocean Photographer of the Year exhibition, showcasing over 100 exquisite images taken by some of the world’s leading professional and amateur ocean photographers. The winning image pictured above, taken by Rafael Fernández Caballero, is just a taste of the spectacular images on display in this stunning exhibition.

A highlight for summer is our brand-new exhibition Ultimate Depth: A Journey to the Bottom of the Sea, which explores the five zones of ocean. The show will feature James Cameron’s incredible DEEPSEA CHALLENGER, a remarkable piece of submersible technology tested in Australian waters and used by Cameron to navigate to the deepest place on earth, the Mariana Trench. This is a not-to-be-missed exhibition, so we look forward to welcoming all to immerse themselves in this exploration of all that lies beyond the ocean’s surface.

We are also excited to be celebrating the 150th anniversary of the Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse, which coincides with its 30th anniversary here at the museum. We look forward to properly honouring this milestone now that the renovations to our boardwalk are complete and access to the lighthouse is no longer restricted.

The opening of our freshly renovated harbour boardwalk has brought new life to the museum, providing patrons with greater accessibility, a greener environment and a beautiful space to soak up the summer sun while exploring our harbourfront. We appreciate your patience while the renovations were ongoing, and hope that this new space can be enjoyed by all.

As always, I would be delighted to hear from the museum family about what matters to you, so please, if you have any ideas, drop me a line to thedirector@sea.museum

I may not be able to respond directly to every person, but please be assured, different voices are both welcome and encouraged.

Daryl Karp AM Director and CEO

The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language. Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The museum is proud to fly the Australian flag alongside the flags of our Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea Islander communities.

Cover Merche Llobera was Highly Commended in the Ocean Wildlife category of Ocean Photographer of the Year with this image taken at Baja California Sur, Mexico. In a dual view of a frenzied hunt, pelicans dive from the sky, while under the water, mahi-mahi chase sardines. See more on page 66. Image © Merche Llobera

2 Tasmanian Hydrowood

An entrepreneurial harvest from drowned forests

12 Calling for entries for $10,000 maritime history prizes

Nominations are now open

14 Operation Navy Help Darwin Commemorating the 50th anniversary of Cyclone Tracy

22 100 years of Halvorsens in Australia

A personal view of a Norwegian–Australian family of boatbuilders

30 Black reefs: friend or foe?

Underwater cultural heritage and marine ecosystems

38 A lifesaving sentinel

The Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse turns 150

46 Preserving our maritime culture

The latest grants and training courses from MMAPSS

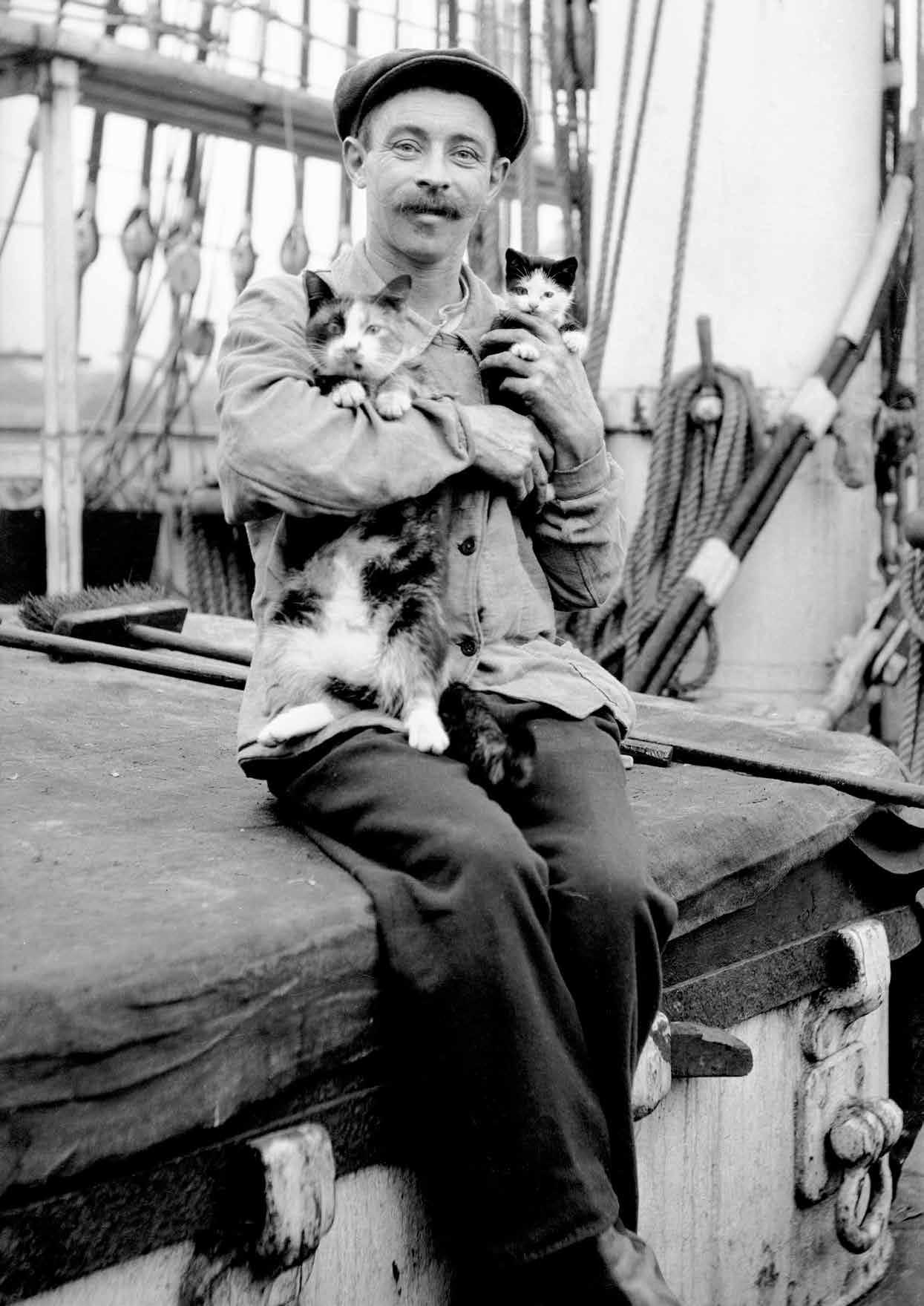

52 Feline seafarers

A history of Australian ships’ cats

58 Foundation news

Supporting sensory-friendly sessions for people with hidden disabilities

60 Our summer program

A preview of events and activations over summer

64 Members news and events

Talks, tours and more

66 Exhibitions

What’s on show this season

70 A new muse

Into the abyss with James Cameron and DEEPSEA CHALLENGER

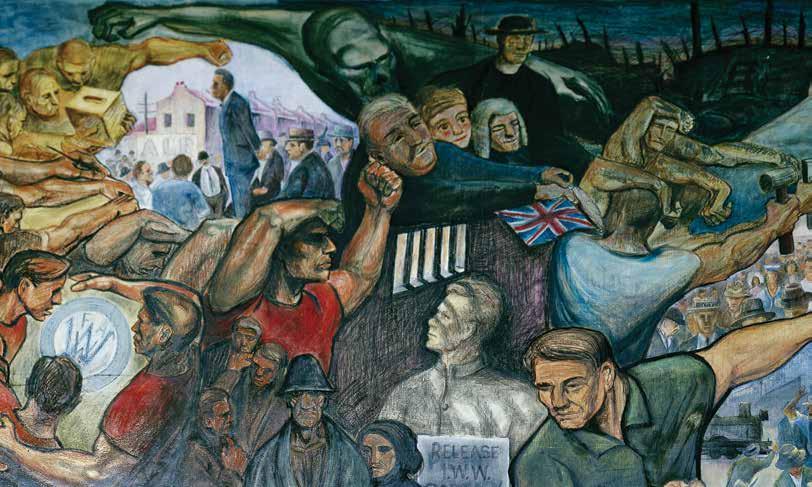

72 Settlement Services International Unlocking the ‘billion dollar benefit’ of skilled migrants

74 Viewings

Seavoice website: exploring the collision of culture and climate

76 Readings

Maritime periodicals; Rock and Tempest: Surviving Cyclone Tracy

82 Currents

Vale Graeme Andrews; Bass Strait Maritime Centre’s new exhibition

When remote Tasmanian river valleys were flooded half a century ago to create the state’s hydro-electricity scheme, countless trees were drowned. An innovative Tasmanian forestry company is now harvesting these beautiful and sometimes rare timbers and giving them new purpose, writes Claire Bennett .

The cold, dark environment of the lake prevents degradation and keeps the timber perfectly preserved

WHEN YOU THINK ABOUT BOATING PURSUITS, forestry is probably far from your mind. And you would largely be right. But in Tasmania, an island famous for its maritime activities, an innovative company is using boats and barges to salvage timber from forests submerged beneath the surface of the state’s hydro lakes. Aptly, the company is called Hydrowood, and it’s making waves.

Hydrowood’s world-first technology uses an excavator atop a barge to reach into the depths to harvest and bring to the surface ancient forest trees, including Huon pine that could be up to 3,000 years old. These dead trees were once part of a lush forest growing beside the Pieman River in a deep valley that was flooded to create Lake Pieman, a hydro-electric dam on Tasmania’s remote west coast. Hydroelectric dams make Tasmania’s energy 100 per cent renewable, and Hydrowood ensures that the forests sacrificed to allow this worthy achievement don’t go to waste.

How Hydrowood began – a flight of fancy Hydrowood co-founder Dave Wise, a pilot, was flying over Lake Pieman following a trip to British Columbia in 2011 when the idea for Hydrowood first sparked: In British Columbia, they float logs out of the forests down rivers. And sometimes, the logs sink. Later these logs can be salvaged, dried, cut and sold, even if they’ve been on the river floor for a very long time. It’s the coldness of the water that preserves the logs. With this knowledge fresh in my mind, I was flying over Lake Pieman looking at the tall treetops reaching out of the lake, and I wondered if they too would be salvageable.

Dave returned home and, over a beer with his friend and later co-founder Andrew Morgan, floated the idea. Andrew recalls:

I think I replied, ‘That’s a bloody stupid idea’ or something to that effect. But never one to shy away from a challenge, and being a few beers in, I soon said, ‘Let’s find out’ and like that, Hydrowood began.

The two entrepreneurs sent divers down to salvage some timber and then engaged the University of Tasmania’s specialist timber research team to see if the timber would be viable. And it was. The university ran many tests to determine the best way to dry the waterlogged timber, but essentially, due to the cold, dark environment of the lake, it was perfectly preserved, just like in British Columbia. ‘The bugger was right!’ says Andrew.

After logs are harvested from beneath the lake, they are transported back to a landing by a

Hydrowood’s specialised operators know both commercial maritime operations and forestry

Today Hydrowood has many investors and is looking to extend its operations into additional lakes in Tasmania and potentially nationally and internationally

Hydrowood was founded in 2012, and Andrew and David have spent over a decade testing the timber in a variety of projects and applications to ensure its quality and durability.

Driving the harvesting barge Hydrowood 1 requires a rare and specialised range of skills. Its skipper needs to hold a Master 5 qualification, which requires six months of sea time and AMSA-approved courses to obtain. Hydrowood 1 captains of recent times are also fishermen; when they’re not harvesting logs from under the water, they might be catching your dinner. It also helps to have experience in forestry because, apart from driving the barge, they need to manoeuvre the harvesting head on the barge-mounted excavator to remove the tree from the water.

Even driving the tugboat Snipe and the other smaller vessels on the operation requires a coxswain’s certificate (three months of sea time and a two-week AMSA course), so Hydrowood is glad to have some experienced personnel who know both commercial maritime operations and forestry.

Today Hydrowood has many investors and is looking to extend its operations into additional lakes in Tasmania and potentially nationally and internationally. It has perfected the salvage and drying process, and the beautiful and sometimes rare timbers are featured in high-end architectural and furniture projects across the globe.

After the precious logs are gathered from beneath the surface, the daily ‘catch’ is towed back to a landing by a tugboat driven by a coxswain. The logs are stacked on the landing before being transferred to the green mill for processing into boards. The boards are then dried to remove the excess water from the timber, with regular monitoring of the timber’s moisture content.

The harvested logs start at around 50 per cent moisture content. They are sawn and racked for 12 months to air dry them, which brings the moisture content down to around 20 per cent. The wood is then placed in a kiln dryer for 6–72 hours to bring the final moisture content down to 8–10 per cent to meet Australian standards. The timber is then sorted and taken from the air-drying facility to the dry mill, or finishing facility, where it is dressed into the final product.

London-based, Tasmanian-born designer Brodie Neill has used over three kilometres of Hydrowood to create ReCoil, an oval dining table. It features veneers of Huon pine, Tasmanian oak, celery top pine, sassafras, myrtle and blackwood, all native to the Pieman River valley. His method uses the smaller and forgotten pieces, such as those discarded from panel production and other processes. Image Mark Cocksedge

Hydrowood is on a mission to ensure that the forests submerged beneath the world’s lakes are brought to the surface and given new life in meaningful ways

The finished timber products perform the same as traditionally harvested timber of the same species

01

Perched on the side of a hill in the seaside town of Lewisham, Tasmania, this tiny house, showcased on Grand Designs Australia, features floor-to-ceiling Hydrowood Tasmanian oak and a custom-made Hydrowood Tasmanian oak veneer couch.

Image Adam Gibson

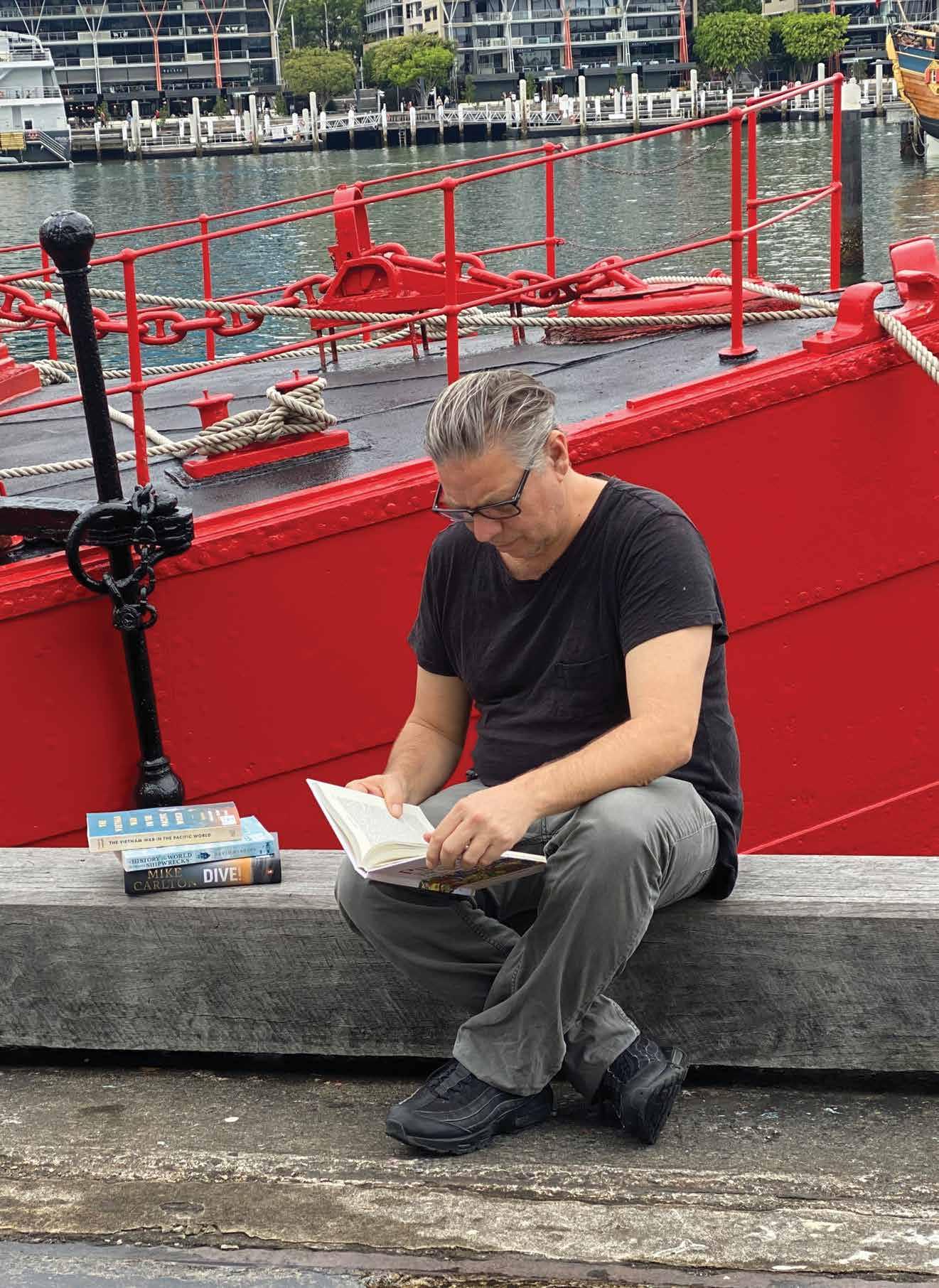

02

Even the smallest pieces of Hydrowood are not wasted, and are crafted into serving boards and small domestic items.

Image Alice Bennett

National and global projects

Hydrowood has achieved significant recognition in Australian projects such as Macquarie House in Launceston, TAS; Limestone House, Toorak, VIC (John Wardle Architects); The Seed House, Castlecrag, NSW (Fitzpatrick + Partners); Lewisham House, Lewisham, TAS (featured in Grand Designs Australia), and Tasmania’s Parliament Square Buildings. In addition, brand partnerships with Snøhetta, Brodie Neill, Jon Goulder, The Museum of Old and New Art (MONA) and a collaboration between Levi Jeans and David Jones have seen the timber brand achieve international recognition. Andrew explains:

The finished timber products perform the same as traditionally harvested timber of the same species. The cold, dark environment of the lake prevents degradation and keeps the timber perfectly preserved. There is no rot or damage of any kind. Andrew notes:

In some cases, the colours are a bit richer from the tannins in the lake, but otherwise, there is no visible trace that the timber has been submerged for decades. With timber in such high demand globally due to its environmental credentials, it would be tragic to let such large volumes of timber go to waste.

Hydrowood is on a mission to ensure that the forests submerged beneath the world’s lakes are brought to the surface and given new life in meaningful ways. It is estimated that up to 300,000 cubic metres of wood may be submerged in lakes Gordon, Mackintosh, Pieman and Murchison on Tasmania’s west coast. The company hopes to work with Hydro Tasmania to ensure the trees under these lakes can also be reclaimed and utilised. And beyond Tasmania, Andrew notes, ‘there are an estimated 300 million submerged trees worldwide, with an estimated value of $50 billion.’

Not only is the timber beautiful, but we’re pulling up species that aren’t readily available from other sources, like Huon pine, blackheart sassafras and celery top pine, which is sought after for its boatbuilding qualities. Plus, people just love the story.

Tasmanian special species timbers are now mostly secured in the state’s vast national park reserves where forestry is prohibited. The most prominent species that Hydrowood harvests are Tasmanian oak and myrtle. With terrestrial forestry operations now only occurring in a small area of younger regenerated forests, supported by plantation-grown eucalypts, the slowergrowing special species timbers are rarely produced.

According to Andrew:

Provenance is such a big part of brands, giving the product meaning that customers can relate to. People are drawn to Hydrowood. They love the idea of sitting around a dinner table talking to friends about where their table’s timber came from and the new life they have given it.

For more information and to find out where to purchase Hydrowood, visit hydrowood.com.au

Claire Bennett is Managing Director and CMO of The Claire Bennett Agency, a multi-award-winning marketing agency based in Tasmania.

Writers, publishers and readers of maritime history are invited to nominate works for maritime history awards totalling $10,000, sponsored jointly by the Australian Association for Maritime History and the Australian National Maritime Museum. Nominations for the next round close on 31 March 2025.

The 2025 Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize of $8,000

EVERY TWO YEARS, the Australian National Maritime Museum and the Australian Association for Maritime History sponsor two prizes: the Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize and the Australian Community Maritime History Prize. Both prizes reflect the wish of the sponsoring organisations to promote a broad view of maritime history that demonstrates how the sea and maritime influences have been more central in shaping Australia, its people and its culture than has commonly been believed.

The major prize is named in honour of the late Professor Frank Broeze (1945–2001) of the University of Western Australia, who has been called the pre-eminent maritime historian of his generation.

This will be the 13th joint prize for a maritime history book awarded by the two organisations, and the seventh community maritime history prize.

To be awarded for a non-fiction book treating any aspect of maritime history relating to or affecting Australia, written or co-authored by an Australian citizen or permanent resident, and published between 1 January 2023 and 31 December 2024. The book should be published in Australia, although titles written by Australian authors but published overseas may be considered at the discretion of the judges. The prize is open to Australian authors or co-authors of a book-length monograph or compilation of their own works.

Fictional works, edited collections of essays by multiple contributors, second or subsequent editions and translations of another writer’s work are not eligible.

The 2025 Australian Community Maritime History Prize of $2,000

To be awarded to a regional or local museum or historical society for a publication (book, booklet, educational resource kit, DVD, film or other print or digital media, including websites, databases and oral histories) relating to an aspect of maritime history of that region or community, and published between 1 January 2023 and 31 December 2024. The winner will also receive a year’s subscription to the Australian Association for Maritime History and a year’s subscription to the Australian National Maritime Museum’s quarterly magazine Signals

Publications by state-run organisations, physical exhibitions and periodicals such as journals are not eligible.

To nominate for the Frank Broeze Memorial Maritime History Book Prize, complete the form at www.sea.museum/history-prizes and provide THREE photocopies or PDFs of the following:

• dust jacket or cover

• blurb

• title page

• imprint page

• contents page

• the page showing the ISBN

• one or two representative chapters of the publication (up to 10 per cent of the contents), including examples of illustrative materials.

A copy of the book may also be included, but may not substitute for these materials. Books will not be returned. Copies of any published reviews may also be included.

To nominate for the Community Maritime History Prize, complete the form at sea.museum/history-prizes and send to the address below, along with:

• For print publications or DVDs – include a physical copy.

• For digital publications such as websites, databases, online exhibitions or apps – include 250–300 words explaining the vision and objectives of the digital media, plus data indicating its success. For websites and databases, also provide the URL or download details.

• For an app or other digital media – submit it on a USB or via a file transfer system.

Copies of any published reviews may also be included.

Multiple nominations may be made, but each must be for one category only. Nominations for both prizes close on 31 March 2025. They should be posted to:

Janine Flew Publications officer

Australian National Maritime Museum Wharf 7, 58 Pirrama Road Pyrmont NSW 2009

Alternatively, email them to publications@sea.museum

Judging process

Following an initial assessment of nominations, shortlisted authors or publishers will be invited to submit three copies of their publication. These will be read by a committee of three prominent judges from the maritime history community.

The judges’ decision will be final and no correspondence will be entered into.

The winners will be announced in the summer 2025 issue of Signals and via other channels in December 2025.

For more information, see www.sea.museum/history-prizes

To mark the 50th anniversary of Cyclone Tracy’s destruction of Darwin, Dr Peter Hobbins outlines the critical role played by the Royal Australian Navy in alleviating the chaos.

‘THIS IS THE NOISE OF THE CYCLONE’, remarked Bishop Ted Collins during an audio recording made on 25 December 1974. ‘It’s almost unbelievable’.1

Disbelief was universal across Australia that Christmas Day. News gradually filtered out of Darwin that a tropical cyclone named Tracy had obliterated the city. The thunderous roar recorded by Bishop Collins heralded winds reaching 300 km/h, with flying wreckage creating a veritable food processor that mashed anything in its path. By dawn, survivors found barely a building standing. Of Darwin’s total population of 47,000, nearly 90 percent became homeless, and three-quarters were evacuated to centres around Australia.

Among the 66 lives lost that night were two Royal Australian Navy (RAN) personnel from HMAS Arrow and three family members of another Arrow sailor. It was one of four Attack class patrol boats that attempted to ride out the storm in Darwin Harbour. When these vessels entered service in the late 1960s, naval architect John Follan advised that ‘their sea keeping qualities are quite good’. 2 Given that HMAS Assail rolled up to 80 degrees during Cyclone Tracy, its commanding officer, Lieutenant Chris Cleveland, likely agreed.

Through skilful seamanship and a little luck, Assail was the only patrol boat to escape with minor damage, by running into the wind and avoiding the many other vessels being blasted across the harbour. Under the command of aptly named Lieutenant Peter Breeze, HMAS Advance – now in the museum’s fleet – suffered gearbox damage and bent blades on its port propeller, while the deck awning was wrenched off. Negotiating the black night without a functioning gyro compass or radar, Lieutenant Paul de Graaf was attempting to avoid a prawn trawler when HMAS Attack went aground at Doctors Gully. All three crews survived, although Attack ’s executive officer broke his foot during the tumult. 3

Of Darwin’s total population of 47,000, nearly 90 per cent became homeless

N7-221

HMAS Arrow, sadly, bore the brunt. After breaking its mooring at 2.45 am, overheating engines left commanding officer Lieutenant Bob Dagworthy with few options. The radar aerial was torn away as he attempted to beach Arrow and the patrol boat slammed into Stokes Hill Wharf.4 With the superstructure crushed and his vessel sinking, Dagworthy ordered ‘abandon ship’. The crew leapt onto the wharf, many being lacerated by oyster shells and coral. For assisting five crewmates to safety, Able Seaman Robert McLeod earned the newly instigated Bravery Medal. Dagworthy himself took to a life raft and was only rescued on Christmas afternoon. Tragically, as author Gary McKay relates, ‘Petty Officer Les Catton was struck by flying cargo, knocked unconscious, and blown back into the water, where he drowned. Another sailor, John Rennie, suffered a similar fate’. 5 After making his way ashore, Arrow ’s Able Seaman Geoff Stephenson returned to the demolished married quarters at HMAS Coonawarra, where he found that his wife Cherry, stepson Kenneth and six-month-old daughter Kylie had been killed.6 Police officer Robin Bullock later recalled ‘the effect it had on him, he was just a shattered man’.7

Having recently taken up the role of Naval Officer Commanding Northern Australia, Captain Eric Johnston had to dig his way out of the rubble of Naval Headquarters. With the RAN transmitting station destroyed, along with most of Coonawarra, he found the navy’s northern bases had little intact infrastructure and no contact with the outside world.

Within hours, Operation Navy Help Darwin was under way, enlisting 13 warships, nine helicopters and 3,000 officers and sailors

‘No one knows better than sailors how to scrub out’

Word of the calamity was, however, relayed across Australia. Within hours, Operation Navy Help Darwin was under way, enlisting 13 warships, nine helicopters and 3,000 officers and sailors.

By Christmas afternoon, numerous units were being stood up and personnel recalled, including HMA Ships Melbourne, Brisbane, Hobart, Vendetta, Stuart, Stalwart and Supply, plus 725, 817 and 851 Squadrons Fleet Air Arm. Within hours the Stores and Victualling branches were procuring fresh, preserved and frozen provisions, alongside bedding, clothing, building supplies and a Bailey bridge. Less than 24 hours after the alert, Melbourne, Brisbane and Stalwart got under way. 8

Yet the first outside naval personnel to arrive in Darwin were medical crews flown in from HMAS Albatross aboard RAN Hawker-Siddeley HS748s, delivering a blood bank on Boxing Day. Just hours behind them were Clearance Diving Team One, led by Lieutenant David Ramsden. His 12-man squad encountered appalling diving conditions: ‘debris of all kinds, combined with poor visibility and the fast flowing tidal streams would have deterred all but the most determined’. 9 They located wrecks, recovered bodies and ammunition, and commenced the salvage of HMAS Arrow. 10

The most urgent necessity was evacuating Darwin’s population. Most residents were airlifted out by Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Lockheed C-130 Hercules and RAN HS748s, alongside commercial airliners.

From 27 December, several hundred evacuees, including naval dependants, were offered transit accommodation at HMA Stations Kuttabul, Watson and Penguin in Sydney. Many just needed a hot drink, a shower, clean clothes and rest. Even one day’s assistance made a big difference to the traumatised survivors, who were ably tended by Women’s Royal Australian Naval Service personnel, navy social workers and wives of Sydneybased sailors. The effectiveness of these measures was soon shown when children became bored and rapidly found ways to create mischief on naval premises.11

Back in Darwin, clearance divers located Arrow on 27 December, subsequently attaching pontoons to the battered hull so that the wreck could be towed to Frances Bay. A post-recovery survey led to the boat being written off and sold, later being scrapped by its overly ambitious civilian purchaser.12

On 30 December, as the first Navy Help Darwin vessels approached the devastated city, the Fleet Commander informed all personnel that the ‘Australian public has very few opportunities to see how their sailors can react in an emergency situation. We are now going to show them’. Specifically, stated Rear-Admiral David Wells, ‘there will be hard, hot and dirty work to be done … We are in Darwin to clear up and no one knows better than sailors how to scrub out’.13

01

A sailor from HMAS Vendetta cleans up a battered Darwin home. Image National Archives of Australia A6180 28/1/75/15

02 Officers and sailors from destroyer HMAS Vendetta plan the initial disaster recovery work. Image National Archives of Australia A6180 28/1/75/24 02

The most urgent necessity was evacuating Darwin’s population

01

The salvaged wreck of HMAS Arrow lying derelict after being sold off in 1975. Note the painted-out vessel number ‘88’ on the stern.

Image Library & Archives NT PH0091/0164

02 Albert Dixon took this photograph of HMAS Advance on Darwin’s cyclone-damaged slipway in January 1975.

Image Library & Archives NT PH0778/0005

Importantly, navy efforts were selfsustaining and did not draw upon fragmented local resources

First on the scene

Guided missile destroyer HMAS Brisbane was earliest on the scene and rapidly enhanced the communications net. The first ship to actually enter the disaster zone, on 31 December, was the recently commissioned hydrographic survey vessel HMAS Flinders, tasked with the essential role of establishing clear approaches and anchorages.14 Extreme caution was required, owing to floating trees, submerged wrecks and the possibility that sandbanks had shifted from previously charted positions.

Offshore, aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne carried seven Westland Wessex helicopters, with two more embarked aboard destroyer tender HMAS Stalwart The first task ashore was to establish a safe landing zone for the helicopters, followed by weatherproofing adjacent buildings to secure landed stores. A similar beachhead was also required for the heavy landing craft (LCH) Balikpapan, Betano, Brunei, Tarakan and Wewak, which transported large cargo items and provided general ferry services.

Both the LCH and Wessex crews worked doggedly. Over the following weeks, the helicopters conveyed 7,832 passengers and 90 tonnes of cargo.15 In addition to providing a welcome overhead presence for survivors, they also conducted searches. On 2 January, for instance, a Wessex crew reported a range of wrecked boats and dinghies that had been driven ashore, albeit with ‘No sign of life in vicinity’.16

Importantly, navy efforts were self-sustaining and did not draw upon fragmented local resources. As vessels anchored and landed sailors, clearance and reconstruction efforts were focused on designated areas to ensure maximum impact, particularly in the suburbs of Nightcliff, Rapid Creek and Casuarina. Working in parties of 15 sailors under a senior sailor or officer, specialist skills were put to work in restoring plumbing and electricity, and making dwellings weatherproof. These tasks occurred alongside general cleanup of debris and the nauseating task of burying rotting food.

An under-appreciated service was rendered by Melbourne ’s darkroom, which rapidly processed photographs for daily assessments and briefings. The well-equipped workshop aboard Stalwart was singled out as a major asset for the rebuilding effort.17 Stalwart also provided secure storage for recovered valuables, while Petty Officer Christopher ‘Timber’ Mills filled in as a guest DJ once local radio station 8DN went back on the air.18

Given the damage to their Darwin base, the three surviving patrol boats could not be repaired locally. An RAAF aircraft delivered a new propeller for Advance, but on 14 January it was determined that ‘both Advance and Assail should be subjected to full hull and principal equipment survey’.19 They proceeded together to Cairns, with Advance utilising only its starboard engine. Attack followed under tow from the frigate HMAS Stuart Once Attack was overhauled, Advance was next on the slip for a total repair bill of $16,539.74. 20

HMAS Stalwart with Wessex N7-221 embarked. Image taken in 1987, during the operation to transport the Cape Bowling Green lighthouse from Queensland to the museum (see story on page 38).

Image Michael Pitcher

Operation Navy Help Darwin provided a welcome publicity boost for the RAN in the fractious years after the Vietnam War

Sailors put in two gruelling weeks ashore, amid the heat, humidity, disarray and stench. By mid-January it was time to pass the baton to the army, the newly formed National Disasters Organisation and civic authorities. HMAS Melbourne departed on 18 January. By local request, Stalwart – with two 725 Squadron Wessexes –remained the last RAN vessel on station, departing with Brisbane on 31 January.

Operation Navy Help Darwin provided a welcome publicity boost for the RAN in the fractious years after the Vietnam War. Flagship HMAS Melbourne ’s contribution was particularly appreciated, given the controversies surrounding its fatal collisions with HMAS Voyager in 1964 and USS Frank E Evans in 1969. 21 ‘Clearly relief operations of the magnitude required by the Darwin emergency could not be foreseen’, asserted Rear Admiral Neil McDonald in May 1975. Yet ‘the ad hoc organisation worked very well indeed, due in no small measure to the dedication of the personnel concerned’. 22

RAN sailors ‘were all part of a team that can only be described as magnificent’, declared Dr Rex Patterson, Minister for the Northern Territory. 23 ‘As the full horror of Tracy became known to Australia’, stated local MP Sam Calder, ‘Navy personnel, both men and women, mobilised to assist in the biggest peacetime operation of the Navy’s history’. 24 When the RAN departed, the Territory’s Administrator, Jock Nelson, wrote to Rear Admiral Wells that ‘the Navy had a tremendous influence on maintaining morale amongst the population and setting Darwin on the road to recovery’. His only complaint was that ‘the people wish the Navy had remained longer’. 25

One of them did. Acclaimed for his energy and integrity throughout the crisis, Captain (later Commodore) Eric Johnston returned to serve as Northern Territory Administrator from 1981 to 1989, and the demolished Naval Headquarters building was rebuilt as his Administrator’s Offices. 26

1 Ted Collins, Cyclone Tracy audiorecording, 25 December 1975. Vaughan Evans Library 363.3492 CYC.

2 JJ Follan, The design of patrol boats for the Royal Australian Navy Sydney: Royal Institute of Naval Architects, 1968, discussion p 5.

3 Tom Lewis, ‘Cyclone Tracy on the attack’, Signals 69, 2004, pp 25–6; Gary McKay, Tracy: The storm that wiped out Darwin on Christmas Day 1974. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin, 2001, pp 64–7.

4 Jack Loney, The price of admiralty: Ships of the RAN lost, 1914–1974 Geelong: Marine History Publication, 1975, p 29; Allen Lyne, Lost: The stories of all ships lost by the Royal Australian Navy Moana Heights: Allen Lyne, 2013, p 294.

5 McKay, Tracy, p 68.

6 National Archives of Australia (hereafter NAA) E794 LIST.

7 Sophie Cunningham, Warning: The story of Cyclone Tracy. Melbourne: Text Publishing Company, 2014, p 67.

8 NE McDonald, ‘Operation Navy Help Darwin’, 20 May 1975, p 3, NAA E499 2-2-4.

9 RS Blue, United and undaunted: The history of the Clearance Diving Branch of the RAN. Garden Island: Naval Historical Society of Australia, 1976, p 29.

10 ‘Clearance diver’s life is not all blowing bubbles’, Navy News , 28 February 1975, p 7.

11 NE McDonald, ‘The Darwin emergency. Assistance provided by HMAS Kuttabul’, May 1975, p 3, NAA E499 2-2-4.

12 Lewis, ‘Cyclone Tracy on the attack’, p 28.

13 Teletext, 30 December 1974, NAA E499 2-2-4.

14 Teletext, 26 December 1974, p 1, NAA E499 2-2-4.

15 David Stevens, The Royal Australian Navy. South Melbourne: Oxford University Press, 2001, p 236.

16 Teletext, 2 January 1975, NAA E499 2-2-4.

17 Chiefs of Staff Committee, minutes of meeting held 15 January 1975, p 4, NAA E203 291/1/D2.

18 Peter Hobbins, ‘When the navy sailed to cyclone-ravaged Darwin’, National Archives of Australia, 14 January 2020, https://www.naa. gov.au/blog/when-navy-sailed-cyclone-ravaged-darwin

19 Teletext, 14 January 1975, NAA E499 2-2-21.

20 Equivalent to $142,300 in 2023. The repairs were fairly modest compared with the impact on HMA Ships Arrow and Assail

21 Timothy Hall, HMAS Melbourne. Sydney: George Allen & Unwin, 1982, p 213.

22 NE McDonald, ‘Operation Navy Help Darwin’, 20 May 1975, p 6, NAA E499 2-2-4.

23 Teletext, 14 January 1975, p 1, NAA E203 291/1/D2.

24 ‘Navy thanked for Darwin effort’, Navy News , 28 March 1975, p 6.

25 JN Nelson to Rear-Admiral Wells, 31 January 1975, NAA E499 2-2-4.

26 Paul Rosenzweig, ‘The role of the RAN and Captain Eric Johnston in the recovery of Darwin, 1974–75’. Sabretache 27, no 4 (1986): 30–2.

Dr Peter Hobbins is the museum’s Head of Knowledge.

Was it due to nature or nurture that I feel tied to the sea, that being on the water brings me peace?

By the age of eight, I was up early to catch and clean fish for breakfast. My grandmother, Bergithe, joined us on our idyllic holidays on Halvorsen hire boats. All images Randi Svensen

Lars Halvorsen arrived in Australia a century ago, establishing a dynasty of highly esteemed boatbuilders and champion sailors. His granddaughter Randi Svensen reflects on growing up in this Norwegian–Australian family.

AS 2023 CLICKED OVER TO 2024, the personal significance of the new year hit home for me. I am Lars and Bergithe Halvorsen’s grand-daughter and this year marks the centenary of the Halvorsens in Australia. It’s been a year of reflection for me. Where do I fit in? Was it due to nature or nurture that I feel tied to the sea, that being on the water brings me peace? Why do I dislike swimming in the ocean? A mantra repeats itself in my head: ‘We like to be on the water, not in it’. Where did that come from? Was I taught the mantra, or is it a remnant of my Viking ancestors’ fear of what may lurk beneath?

I am genetically 100 per cent Norwegian. My mother, Margit Elise Halvorsen, married Norwegian merchant seaman Arnold Svensen, who landed in Sydney during World War II and stayed ashore after an asthma attack. Papa went on to join the Norwegian foreign service and was posted to Australia for decades, so my childhood, and that of my siblings, was unusual. We were born in this country but because of Papa’s job, we were raised as Norwegians. Not fully assimilated, but likewise not living in the country we thought of as ‘home’.

My mother’s childhood had been more of the usual migrant one, of trying to fit in with other ‘new Australians’, but her marriage to my father required that she return to her Norwegian roots. We spoke Norwegian at home and sometimes, when Mama and I were in public, she would speak to me in Norwegian and I’d reply in English, attracting some very puzzled looks. Even our food was different. I was the only kid in my class who actually loved Brussels sprouts, and I still crave fish, as if it’s something my body must have.

The other anniversary of significance to me in 2024 is that it is 20 years since the release of my family history, Wooden Boats, Iron Men – the Halvorsen story, which was published with the support of the Australian National Maritime Museum. I wrote it with the permission and co-operation of my mother, uncles and aunt. When I began researching the story, in everyone’s eyes I was still ‘little Randi’, the youngest child of the baby of the family. But I knew it had to be done then, or the stories would be lost or, worse, bastardised. The result was intended only for family consumption, but I ran the manuscript by Jeffrey Mellefont, then-publications manager of the museum, and he thought the story had significance for Australia. He encouraged me to take it further.

What followed surprised me. The manuscript was published by Halstead Press and the first print-run sold out in weeks. Two more print-runs followed. I don’t claim credit for that: it was the Halvorsen name and legend that interested my readers – the romanticism, if you like, the derring-do. And, of course, the beautiful boats.

Lars’ pronouncements included, ‘If you can build a boat, you can build anything’

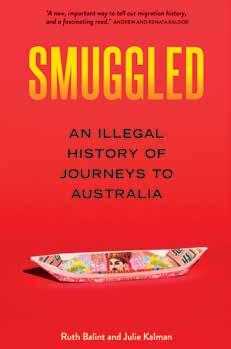

These photos show my great-grandfather, Karl Klemmetsen (Bergithe’s father), my great-great-grandfather, Hans Arentz Andersen, and my great-great-greatgrandfather, Johan Petter Juell, who were all sea captains. Bergithe is the older child in the lower middle photo, with her brother Magnus. The baby is Bergithe’s sister Karoline. Sadly, neither Magnus nor Karoline survived beyond infancy.

As part of my research, I had traced Bergithe’s line back 500 years. Learning more about my forebears has explained some of the mystery of where my uncles’ sailing ability came from. Bergithe’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather were sea captains. I have a photograph of my great-great-great grandfather, Captain Johan Petter Juell, who was born in 1797 and who lived to 90, and a letter copy-book kept by my great-great-grandfather, Captain Hans Arentz Andersen, which dates from 1860 to 1864, his letters sent from far-flung ports. Captain Karl Klemmetsen, my greatgrandfather, was said to have made it as far as Australia, although sadly we have no proof of it.

On Lars’ side, the birth of Halvor Andersen’s tenth child, my grandfather Lars Gustav, was the catalyst for Halvor learning boatbuilding at the age of 58. At first it was to supplement his income from farming, but demand for his high-quality vessels soon saw him focusing on his new trade, one that Lars took up when he left school, ultimately setting up in competition with his father. From family lore and my reading of Lars’ extensive scrapbook, Lars was driven, dogged and strict, but also kind. He was passionate about polar exploration but also seemed to have a sense of humour, as shown in the clipping of a long alliterative piece, in Norwegian, about a seaman and his love. Lars’ pronouncements included, ‘A boat is only as good as its bilge pump’ and ‘If you can build a boat, you can build anything’, and they entered the family lexicon. His unexpected provision of sails and ropes on the first boat he built for Burns Philp created a family saying ‘sails and ropes’ to describe going the extra mile.

It’s important to remember why Lars and Bergithe left Norway. In 1919, anticipating a demand for ships after World War I, Lars built, on spec, the 350-ton wooden cargo vessel Nidelv. But the ship didn’t sell, so Lars partnered with a ship’s chandler to operate it with a paid crew. When Nidelv was stranded on a sandbank in Wales in 1921, the ship was wrecked, although the crew were able to simply walk ashore to safety. But due to a huge increase in insurance premiums as wooden ships were being abandoned in favour of steel, Nidelv was then uninsured and Lars lost everything, including the land that had come through Bergithe’s family and on which they had built a house and substantial boatbuilding yard. Lars owed money to the local community bank, and many of his friends and neighbours suffered after the loss of Nidelv. It must have been mortifying for both Lars and Bergithe, who had close ties to the community.

When Bergithe was pregnant with her seventh child, my mother, Lars travelled to Cape Town, tasking his wife with selling what she could and bringing the children (Margit then only two months old) to join him. Two years later, having heard great things about Sydney Harbour, Lars again upped sticks and travelled to Sydney, arriving in late 1924. The eldest son, Harold, then 14 and old enough to help his father, arrived shortly after. Bergithe and the other six children arrived in February 1925. The first substantial Australian-built Halvorsen boat, the 30-foot yacht Sirius, was launched in June 1925.

While I documented the story in Wooden Boats, Iron Men as well as I could with the information I had, one thing that has since come up changes some of the narrative. In the book, I described Lars’ death as being from osteomyelitis of the spine. That was the diagnosis in 1936, but my later research put the most likely culprit as Potts disease, a spinal infection caused by the tuberculosis (TB) bacterium. In his desire to help visiting Scandinavian seamen, a couple of years before he fell ill, Lars had brought home a young man who had advanced TB. TB bacteria can lie dormant before manifesting in the spine, and I now believe this was the most likely scenario.

As a child, I was close to ‘the uncles’, particularly Bjarne, Magnus and Trygve, and I still miss them – their counsel, their humour and their company. To be in their orbit was to feel safe and loved. While they are often referred to as ‘the Halvorsen boys’, they had very different personalities: Harold, Managing Director of Lars Halvorsen Sons because he was the eldest, always seemed to me to be just a little aloof. Carl was vibrant and outgoing. Elnor was serious but nurturing and kind. Bjarne was a personality writ large, with a wonderful belly laugh. In school holidays, I sometimes ‘helped’ in Bjarne’s boatbuilding yard office and, at age 12, was entrusted with counting and delivering cash wages to the workers. Bjarne gave me self-confidence and called me ‘little one’. Magnus gave me snippets of life advice and called me ‘cuz’. Trygve was cheeky and fun, but was always willing to teach me how to read the wind or judge the depth of the water. He showed me how a well-set sail should look and I remember my lessons in how to achieve a smooth finish with varnish. I was probably seven years old at the time. Uncle Trygve pronounced my name ‘Rundy’ in his guttural southern Norwegian accent.

01

My brother Paul, family friend Tom Jensen and I used to love sitting on the foredeck as we motored to our favourite destinations of Refuge Bay and Coasters Retreat. We always slept very well with the salt air and the sounds and smells that are unique to a timber vessel.

02

Co-skippers Magnus (standing) and Trygve departing for Hobart on Saga in 1946. This photo graced the bulkhead of my own classic yacht, also named Saga After my uncles’ deaths, the first time I boarded it felt as if they were waving a final farewell to me.

02

As a child, I was close to ‘the uncles’, particularly Bjarne, Magnus and Trygve, and I still miss them

I saw nothing strange about going sailing on Sydney to Hobart–winning yachts

With the naivete of childhood, I thought my uncles would win any race they entered (and they almost always did) and I saw nothing strange about going sailing on Sydney to Hobart–winning yachts or spending a couple of weeks a year on one of the hire cruisers, along with my mother and grandmother Bergithe. When my brother Paul and I were planning to build a cubby house or billy cart, Mama would take us to the yard at Ryde to collect timber offcuts for our creations. Since we went on weekends, the yard was empty, so Paul and I would climb onto half-finished boats to explore, and slide across the floor in skips that were on rails. One of our favourite projects was a retired dinghy that sat in our backyard and which Paul fitted out with two cabins. Even to this small fiveyear-old, it was cramped, but it was such an adventure, pretending we were at sea!

Spending time in the snow was another Norwegian ritual, and every year we spent two weeks at ‘Telemark’, a mountain hut built by Papa, my uncles and a few friends in Perisher Valley in 1952. I was skiing not long after I could walk and by age five was expected to eschew the dog sled and ski the three kilometres from Smiggin Holes to the hut, my child-size rucksack on my back. There was no electricity, and food was kept in a cage outside in the snow so the foxes couldn’t get it. We could see their red eyes outside at night. Cooking was done on the massive granite fireplace and light was provided by oil lamps. The uncles hand-made our little skis.

01

Paul and I had sailing adventures, even on land!

02

Despite looking terrified in this photo, I loved our sailing outings with Uncle Trygve, who taught me how to ‘read’ the wind and water.

03

Uncle Carl with my son Carl, who was named for both his great-uncle and his great-great-grandfather, Karl Klemmetsen (the spelling was interchangeable). When ‘young’ Carl began as an apprentice shipwright, Uncle Carl was visibly moved, proudly declaring, ‘Båtbygger ‘[boatbuilder] Carl!’

While it was Lars and his father’s passion for craftsmanship that made the boatbuilding legend, it was Bergithe’s seafaring ancestors who were the link to her sailing sons. I can see Lars’ dogged determination in my son, Carl Juell, who trained as a shipwright. ‘Young’ Carl has a perfectionist’s eye and a passion for working with wood. And I see Bergithe’s strength in my daughter, Camilla Bergithe, who not only physically resembles her namesake but is just as fiercely intelligent and tenacious.

How much is nature and how much nurture?

I still don’t know.

Randi Svensen is the author of Wooden Boats, Iron Men – the Halvorsen Story (VEL 623.82 HAL); Heroic, Forceful & Fearless: Australia’s tugboat heritage (VEL 623.8232 SVE); Nuts and Bolts and Petticoats: how the Nock and McCathie families shaped retailing in Australia; and A Changing Tide: the history of Berrys Bay, Sydney Harbour, 33.83S, 151.18E (VEL 623.8209941 SVE)

Reef-top anchor at Boot Reef with its concretion layer generally well intact. Note the flash rusting in a damaged small area in the foreground. The anchor is not near the edge of the reef which is most exposed to wave action, as the wreck seems to have been pushed over the reef for quite a distance before it broke apart. Image Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation

A cultural heritage object, including a shipwreck, has depth, meaning, connection and impact beyond what is initially evident

‘Underwater cultural heritage’ refers to items and artefacts that end up on the sea floor. Whether as small as a nail or as large as a ship hull, they can affect their environment in different ways, one of which is the phenomenon of ‘black reefs’. Irini Malliaros explains.

A SHIP IS WRECKED, resulting in chaos, tragedy and loss. Yet, given enough time, the shipwreck and its story can become a source of wonder, a reason for adventure and discovery, a site full of potential and a source of creative inspiration.

We often think about what a ship and its wrecking event mean to humans – those on board at the time, or their families and descendants; those who owned, salvaged or bought the wreck; or those who, decades or centuries later, rediscovered it. The consequences of a wreck, however, extend far beyond the human world.

An artefact – whether large, such as a ship, or small, such as an object it carried – is like the centre of a web. As someone whose profession is investigating such webs, I often perform a thought experiment; I imagine the whole story from different points of view, such as that of an object lost in the wreck, or of a fish or a coral that lives near where the shipwreck rests. To what end, one might ask; why think of it this way? Well, put simply, a cultural heritage object, including a shipwreck, is not just a thing – it has depth, meaning, connection and impact beyond what is initially evident. Applying this thought experiment gives us a more holistic view.

Let’s take, as an example, vessels that run aground on reefs. The crest of the reef is its highest and therefore shallowest part, often exposed at low tide. This is where ships are most likely to come to grief or to spill onto after hitting the upper reef slope. Reef crests are generally dynamic environments, experiencing the strongest winds and roughest wave action. A wooden vessel is likely to break up relatively quickly by the actions of physical, chemical and biological agents, particularly if it struck the side of the reef that is exposed to prevailing weather and seas. The components of a wooden vessel that usually survive the longest are composed of inorganic materials such as metals (anchors, sheathing, metal fasteners, iron knees, chain), ceramic or glass. If the vessel has an entirely metal hull, it will usually remain relatively intact for a longer period.

Now, let’s transfer our point of view to that of a fish living on the reef. One stormy night a big ship crashes onto the reef and becomes so damaged that it is abandoned by the humans on board. Over the next days, weeks or months, the abandoned vessel is pushed and shoved onto the reef by wave action, rolling back and forth, crushing and gouging out large sections, causing mechanical damage to the very structure of the reef. Finally, the vessel may break apart enough for sections of it to detach and drift off, in the case of a wooden vessel. Or, if it is a metal ship, it may eventually dig itself into a spot and settle in. But what happens after a much greater span of time, such as 150 years or more?

Over time the wreck, or parts of it, begin to affect the surrounding habitat in different ways. This is particularly evident in the case of iron components, as sea water causes iron to corrode. As years turn into decades and even centuries, the corroding iron is released into the water column around and down-current of the wreck.

Iron is a limiting resource in natural environments, meaning that organisms that thrive on it are constrained by its supply.1 Iron occurs naturally in some areas of the ocean, but in relatively small quantities, and many coral reef environments are generally iron poor. The presence of large iron objects – anchors, knees, chain, even an entire ship hull – increases the amount of iron available. This enables the prolific growth of organisms that are otherwise limited by its supply, such as seaweed and cyanobacteria – often to the detriment of others, such as corals.

01

A metal-hulled shipwreck from the 1950s on Palmyra Atoll, central Pacific Ocean, was actively deteriorating with flash rusting, causing a phase shift in its surrounding environment. The US Fisheries Pacific Region intervened and removed 126 tonnes of the rusting material. Image Susan White/ US Fisheries Pacific Region

02

A single Admiralty pattern anchor from the 1850 wreck of the British barque Jenny Lind, on Kenn Reefs in the Australian Coral Sea Territory. Note the blackened area all around it. Various wrecks on Kenn Reefs were investigated by a team from the museum and Silentworld Foundation in 2017. Image Irini Malliaros/Silentworld Foundation

Is the impact of underwater cultural heritage on its surrounding environment positive in any way?

The term ‘phase shift’ 2 is given to dramatic change, be it immediate or gradual, from a coral-dominated reef ecosystem to one that is depleted of hard coral and dominated by macroalgae (seaweed) and/or corallimorphs (soft corals).

Events such as extreme weather (including cyclones), pollution or run-off can disturb an ecosystem sufficiently to cause such phase shifts. 3 ‘Black reefs’ is the term given to a shift related to the presence of iron in an otherwise iron-poor environment. The term accurately describes the change that occurs, as the organisms that come to dominate the new environment near the wreck are brown to black. This colouration contrasts with the unaffected parts of the reef.4

The phenomenon of black reefs has been noted and studied at some sites of modern shipwrecks dating from the 1970s onwards. 5 However, little work has been done on the effects a historic wreck may have on its surrounding environment over a longer time – so we now adjust our lens to focus on sites from around the 1870s or earlier.

In 2017, archaeologists from the Australian National Maritime Museum and Silentworld Foundation noted the dark colouration typical of ‘black reefs’ on satellite imagery following an expedition to Kenn Reefs in the Coral Sea. These dark areas were directly associated with shipwreck sites 170 years and older that had been ‘ground-truthed’, or physically sighted and recorded during field work, by the team (see image 02 opposite).6 At the time, we aimed to use the concept as a predictive model while planning future expeditions to identify sites of interest for ground-truthing while on location. We put this plan into action at the end of 2018 on the very next expedition to Boot Reef, where the black reefs effect as seen on satellite imagery was extremely subtle. The wreck was not near the weather edge of the reef and the imagery had been obtained following an extreme weather event that had caused coral die-off and a consequent change in the colour of the reef top, making it difficult to clearly pinpoint areas of black reef.7

01

Porter-patent anchor with coral growth. Recovery from the ‘black reef’ phenomenon – essentially a reversal of the phase shift – is possible and was observed on deeper sites at Kenn Reefs. Possibly due to its depth, the site was not reached by regular wave action and therefore the concretion (the underwater cultural object plus the mass of natural growth attached to it) remained intact. This ensured that very little iron was released from it, so the iron-dependent species numbers were kept lower and the conditions were suitable for coral recruits once more. Image Julia Sumerling/Silentworld Foundation

02

A satellite image of the black reefs phenomenon: wreck artefacts on remote Kenn Reefs in the Australian Coral Sea Territory are indicated by the presence of black streaks, caused by iron objects disintegrating into the water column. Satellite image DigitalGlobe Imagery; overlying notation Silentworld Foundation

Underwater cultural heritage: positive or negative?

Since that time, my understanding of this field has grown, as has my view of its potential. Wearing both my maritime archaeologist and biologist hats simultaneously, I am inclined to take a more deeply probing approach to try to explore and understand the full potential of the interaction between underwater cultural heritage (UCH), including but not limited to shipwrecks, and the surrounding ecosystems to produce data that can inform a wide range of interrelated research facets with realworld applications.

For example, is the impact of UCH on its surrounding environment positive in any way? UCH in some cases is viewed as potentially creating habitat for organisms. We are now asking questions that fling us into the wider parts of that web radiating from the object – does the object’s surface provide a substrate for the development of a habitat that is appropriate and suitable? 8 Is it attracting and accommodating indigenous organisms or is it a structure that either introduces or recruits non-native species? 9 Does the UCH habitat attract mobile indigenous species away from their nearby natural habitat and, if so, what impact does this have on them and the habitat they have abandoned? 10

The phenomenon of black reefs has been noted and studied at some sites of modern shipwrecks dating from the 1970s onwards

Growth around the Boot Reef anchor – some small corals and green and brown slimy-looking algae on the shank and on the dead corals beside it. Image Irini Malliaros/Silentworld Foundation

Where UCH is in near-shore environments, it may be used for heritage tourism, which may be of benefit to the local community. In addition to the income generated from visitors, the fish populations that aggregate on the site may be of value to local fishers. However, are the fish on site appropriate for human consumption, are they absorbing harmful substances from the UCH, or are they displacing fish of a higher economic value? 11

Conversely, how are the surrounding environment and its processes affecting the cultural heritage item? Are crashing waves degrading it? Are organisms slowly destroying it? And what of human activities – are fishers or divers or human-generated pollution contributing to its degradation?

Most of the work conducted, and still continuing, on these and related topics has been carried out on modern shipwreck sites. But what is the impact of all these factors if the object remains on location for 150 years and more?

Logically, we can begin assessing older sites by applying some of the methods used to investigate recent wrecks and by using studies on artificial reefs. Collecting and collating comprehensive data in this manner will inform and assist us to actively monitor and manage underwater cultural heritage on coral reefs and in other habitats.

1 A Butler (1998). ‘Acquisition and utilization of transition metal ions by marine organisms’, Science no 281(5374): 207–9; B Entsch, R Sim and B Hatcher (1983). ‘Indications from photosynthetic components that iron is a limiting nutrient in primary producers on coral reefs’, Marine Biology 73: 17–30.

2 TJ Done (1992). ‘Phase shifts in coral reef communities and their ecological significance’, Hydrobiologia 247: 121–32.

3 B Hatcher, R Johannes and A Robinson (1989). ‘Review of the research relevant to the conservation of shallow tropical marine ecosystems’, Oceanography and Marine Biology 27: 337–414.

4 This article focuses on the effects of shipwrecks on reefs, but it should be noted that shipwrecks are not the only source of increased availability of iron in reef environments.

5 B Hatcher (1984). ‘A maritime accident provides evidence for alternate stable states in benthic communities on coral reefs’, Coral Reefs 3(4): 199–204; R Schroeder, A Green, E DeMartini and J Kenyon (2008). ‘Long-term effects of a ship-grounding on coral reef fish assemblages at Rose Atoll, American Samoa’, Bulletin of Marine Science 82: 345–64; TM Work, GS Aeby and JE Maragos (2008). ‘Phase shift from a coral to a corallimorph-dominated reef associated with a shipwreck on Palmyra Atoll’, PLoS ONE 3(8): 2989; LW Kelly, KL Barott, E Dinsdale, AM Friedlander, B Nosrat, D Obura, E Sala, SA Sandin, JE Smith and MJ Vermeij (2012). ‘Black reefs: iron-induced phase shifts on coral reefs’, The ISME Journal 6(3): 638–49; S Mangubhai and DO Obura (2018). ‘Silent killer: black reefs in the Phoenix Islands Protected Area’, Pacific Conservation Biology 25(2): 213–14; V Van der Schyff, M Du Preez, K Blom, H Kylin, NSCK Yive, J Merven, J Raffin and H Bouwman (2020). ‘Impacts of a shallow shipwreck on a coral reef: A case study from St Brandon’s Atoll, Mauritius, Indian Ocean’, Marine environmental research 156: 104916 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2020.104916

6 J Hunter and I Malliaros (2017). ‘Wreck of the Jenny Lind: The Kenn Reefs archaeological survey’, Signals 119: 8–13; I Malliaros and J Hunter (2017). ‘The Colours of Wrecks’ in Ongoing Projects Blog, Silentworld Foundation <https://silentworldfoundation.org.au/the-colour-ofwreck/>, accessed 12 August 2024.

7 K Hosty, J Hunter, I Malliaros and P Hundley (2019). ‘Black reefs and the “Jardine Treasure” – The Boot Reef Project 2018’. Signals 126: 19–25.

8 JHR Burns, KH Pascoe, SB Ferreira, H Kane, C Kapono, TL Carrell, A Reyes and A Fukunaga (2023), ‘How do underwater cultural heritage sites affect coral assemblages?’, Remote Sensing 15(8): 21–30.

9 A Hylkema, QCA Hakkaart, CB Reid, R Osinga, AJ Murk and AO Debrot (2021). ‘Artificial reefs in the Caribbean: A need for comprehensive monitoring and integration into marine management plans’, Ocean & Coastal Management 209: 105672.

10 J Bohnsack (1989), ‘Are high densities of fishes at artificial reefs the result of habitat limitation or behavioral preference?’, Bulletin of Marine Science 44: 631–45.

11 NL Crane, MJ Paddack, PA Nelson, A Abelson, J Rulmal and G Bernardi (2016). ‘Corallimorph and Montipora reefs in Ulithi Atoll, Micronesia: documenting unusual reefs’, Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation 21(2016): 10–17.

Irini Malliaros is the founder and director of I AM Archaeology: Habitat & Heritage.

Transplanted from its original Queensland location after it was decommissioned, the Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse has stood on the museum’s waterfront for 30 years.

ANMM image

This year, the museum commemorates the 150th anniversary of the Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse and 30 years since it reopened on the museum site at Darling Harbour in Sydney. Curator Inger Sheil relates episodes in the life of the lighthouse and the ships that it relied on it.

A SOUTHERLY BREEZE WAS BLOWING as SS Grantala departed Townsville at around 4 pm on 23 March 1911. The Adelaide Steamship Company’s 3,655-ton coastal steamer was southbound from Cairns, calling at ports on route to Melbourne. ‘Good steaming weather’, one of her officers described it, but as the ship approached Cape Bowling Green, 70 kilometres to the south, at 7.30 pm that evening, Captain James Sim was alert to a change in the weather.1 The wind had picked up, the barometer was falling and it was cyclone season – a week before, a devastating storm had struck Port Douglas, killing two people and destroying most of the town. Sim decided to seek shelter in Bowling Green Bay.

The light station at Cape Bowling Green was the second in a series of lighthouses built to the same ‘ironclad’ design

Since 1874 the Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse had stood watch over this stretch of coast, alerting marine traffic to the 22-kilometre low sandy spit that could be difficult to distinguish from its surrounds until it was too late. A history of ships running aground in the vicinity had prompted the people of the newly founded settlement of Townsville to call for a lighthouse. The light station at Cape Bowling Green was the second in a series of lighthouses built to the same ‘ironclad’ design, comprising a local hardwood frame clad with iron plates imported from Britain. The ironbark frame was assembled at the Union Saw Mill in Maryborough then disassembled in June 1873 for transport to Cape Bowling Green, and the plates were prefabricated in Brisbane before being affixed to the re-erected frame on site, ensuring an economical construction in a remote, inaccessible location.

The Rooney Brothers, who had previously built the light towers at Sandy Cape and Lady Elliot Island and were familiar with the construction techniques involved, were awarded the contract to build the light tower. Work commenced in July 1873, overseen by John Rooney, and was completed on 3 October 1874.

More wreckage from the ship would drift ashore along the coast in following days

01 Coloured postcard of the Adelaide Steamship Company’s SS Grantala, date unknown. ANMM Collection ANMS0047[113]

02 Plan of Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse, drawn by David Payne in 2003. ANMM

Thirty-six years later, Captain Sim ordered Grantala into a position 11 kilometres west-northwest of the sentinel lighthouse, staying well clear of the shallows that extended far out from the shoreline, dropping both anchors in preparation for the night to follow. His decision proved wise as the wind built to cyclonic strength, accompanied by heavy squalls of rain. Grantala ran out 100 fathoms (180 metres) of cable to ride out the storm at anchor. The cyclone reached its height in the early hours of the morning; so strong were the rain squalls that, at intervals, they even obscured the Cape Bowling Green Light’s 13,000-candlepower beam that would normally be visible at 25 kilometres. 2 But as crew and passengers waited through the night, Grantala held its own against the onslaught, on a night that Sim would later describe as one of the worst he had ever experienced. 3

Conditions were no less alarming in the light station itself. In the three lightkeepers’ cottages, the keepers and their families were at the mercy of the deteriorating weather. The cottages shook and the beds rocked on the floor; Superintendent John Kidd, head lighthouse keeper since 1902, feared the roof would lift or the structures might be carried off in their entirety. The following morning, he found his small garden buried in sand up to the top of the one-metre paling fence that surrounded it, and two metres of sand piled up against the walls of the cottage.4

The lonely job of tending to the light in the 22-metre tower in the early hours of the morning fell to Assistant Keeper Thomas Carter, who had 16 years’ experience in lighthouses. Struggling to stay on his feet as the light tower shook and vibrated violently, he thought it was the wildest night he had yet seen. In addition to the movement of the tower, the drop in pressure had made it more difficult to keep the kerosene-fuelled light burning, and he had to keep a constant watch lest the vital flame go out.

But the storm passed, the wind came around towards the north and the barometer rose. Normal operations could proceed, and by the following morning Grantala was once again under way. As they reached the mouth of the Brisbane River late on 27 March, they were signalled by the keepers of the Moreton Bay Pile Light, urgently asking if they had seen anything of Grantala ’s sister ship, SS Yongala, which was overdue. 5

01

Captain John Anderson Kidd and his wife, Esther Jane Prance Kidd, at the Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse. John Kidd was the lighthouse superintendent from 1902 to 1912. Image Burdekin Shire Council Library Services

02 Lanterns at the Yongala wreck site as shot by Ron and Valerie Taylor during filming of their documentary on the shipwreck in the early 1980s. ANMM Collection ANMS1458[018] Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Valerie Taylor in memory of Ron Taylor

03

Unidentified lightkeeper and family in front of a Cape Bowling Green Light Station cottage c 1914. Australian Maritime Safety Authority Collection

In the three light keepers’ cottages, the keepers and their families were at the mercy of the deteriorating weather

Yongala was last seen heading north on the evening of 23 March by the keepers of the Dent Island Light. The keeper on watch noted the time as 6.30 pm and observed that the steamer was on its usual track and in its usual trim. It was in sight for 20 minutes until passing out of view, obscured by the squalls sweeping the coast.6

In the following days searchers were dispatched and vessels at sea kept a keen lookout for any sign of the missing ship. Early on the morning on 28 March, the keeper on watch in the Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse noticed what appeared to be wreckage in the water. Superintendent Kidd’s daughter, Essie, patrolled the beach in the following hours and found bags of chaff, bran, pumpkins and pollard rolling in with the waves. Kidd telegraphed the Adelaide Steamship Company’s Townsville office,7 which confirmed that the markings on the bags corresponded with cargo stowed in Yongala ’s lower, number three hold. 8 This was not deck cargo that might have been washed overboard – its location deep in the holds indicated a catastrophic accident had befallen the ship. It was the first real confirmation that Yongala had been lost.

Although more wreckage from the ship would drift ashore along the coast in following days, it was not until 1958 that the wreck was located, lying 22 kilometres east of Cape Bowling Green. The site is the final resting place of 122 passengers and crew, among them

Matthew Rooney, his wife Katherine and their daughter Elizabeth. Matthew was one of the founders of the Rooney Brothers firm, builders of several Queensland lighthouses, including the Cape Bowling Green Light.

Some stories connected with the lighthouse had happier endings. In early September 1874, as work neared completion on the light station, John Rooney and the first Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse keeper, Henry Lander Pethebridge, were startled by the sudden arrival of an open boat with eight shipwrecked sailors. Their ship, the 1,021-ton Guinevere, had wrecked on Pocklington Reef in Papua New Guinea and its 29 crew were forced to take to three open boats. They made the daring decision to sail south to the Australian coast, a voyage of some weeks in which the boats became separated. One boat did not sight land until coming to Palm Island, north of Townsville. The crew were unaware of any European settlements further north than Bowen until they came alongside Cape Bowling Green and saw the welcome site of a new lighthouse. 9 Rooney and Pethebridge met the crew and provided what hospitality they could before directing them on to Townsville.10 Over the following days the other two boats made landfall as well, having made the 1,300-kilometre voyage without a single fatality.

Superintendent Kidd’s daughter, Essie, patrolled the beach and found bags of chaff, bran, pumpkins and pollard rolling in with the waves

In the following months changes will be coming to the lighthouse 01

Cape Bowling Green Light Tower being re-erected on site at the museum. ANMM image

02

Cape Bowling Green Lighthouse, pictured in 1987, watched over its original location for 113 years. Image Mike Lorimer, Ove Arup and Partners

Cape Bowling Green Bay, today part of a national park that includes diverse landscapes ranging from mountain ranges to coastal estuaries, presented some unusual challenges to the families that lived there. The mangroves near the lighthouse provided an abundance of both stinging insects and – far more welcome – mud crabs, but were also a habitat for more dangerous predators. By 1892, erosion had necessitated moving the keepers’ cottages 335 metres away to safer ground. At high tide the keepers used a skiff to cross to the lighthouse. On the night of 27 August 1892, Assistant Keeper James Rose was making the crossing when he was attacked by a crocodile. Rose escaped the terrifying encounter by climbing a telegraph pole, from which Superintendent Richard Cole was able to rescue him with a dinghy.11

As the lighthouse approaches 30 years at the Australian National Maritime Museum, conservation and curatorial staff have developed an object management plan to document the history and material fabric of the tower, manage future conservation works and develop new interpretations for visitors. Among other initiatives, the museum commissioned a comprehensive structural engineering report from heritage experts Partridge to document the current condition of the light tower and identify any major issues.

In the following months changes will be coming to the lighthouse, from new interpretation panels sharing the narrative of the light and the community that developed around it, to a more discreet security barrier enabling better visitor flow. We are exploring ways of using innovative technology to make the lighthouse accessible for a wider audience online. Visitors will be able to enjoy new digital experiences, exploring the view from the top with a virtual tour, zooming into the details with 3D photogrammetry and discovering new stories on our updated website. We invite you to explore the rich history of this lighthouse that stood through storm and rain, and the people who kept the light going no matter how much their world rocked and the tower trembled beneath their feet.

1 ‘Grantala ’s Experience’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 31 March 1911, p 9.

2 Ibid

3 ‘Voyage of the Grantala ’, The Age, 28 March 1911, p 6.

4 ‘More Wreckage at Bowling Green’, Queensland Times , 31 March 1911, p 5.

5 ‘The Yongala ’, The Evening Telegraph, 30 March 1911, p 6.

6 ‘Grantala ’s Experience’, op cit

7 ‘Passed All Right’, Daily Telegraph, 30 March 1911, p 7.

8 ‘More Wreckage at Bowling Green’, op cit

9 ‘Wreck of the Guinevere ’, Evening News , 26 September 1874, p 2.

10 Ships’ Mails, The Sydney Morning Herald, 8 October 1874, p 4.

11 ‘Attacked by an Alligator [sic]’, Warwick Argus , 30 August 1892, p 2.

For almost 30 years, the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme has assisted maritime museums and heritage institutions across Australia to develop, present, preserve and interpret their collections.

Peter Drogitis profiles three projects that were successful in the latest round of grants.

SINCE 1995, THE AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT has funded an annual program of small-scale grants and internships through the Australian National Maritime Museum and the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts. To date, the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme (MMAPSS) has provided more than $2.5 million in funding for over 550 projects and facilitated 85 museological training courses at the Australian National Maritime Museum.

The Australian landscape is threaded with rivers, lakes, estuaries and other bodies of water, and our home is also ‘girt by sea’, as our national anthem famously states. Within all these waters the history of our continent stretches back millennia. Through MMAPSS, many maritime bodies have gained funding to provide greater opportunities for the public to engage with the country’s maritime history.

Past grants have aided the restoration and conservation of significant vessels and helped to develop many exhibitions, from those exploring Aboriginal connections with land and water to others on the history of shipwrecks around our coast.

This year’s scheme provided $130,000 to be dispersed across multiple institutions nationwide

01

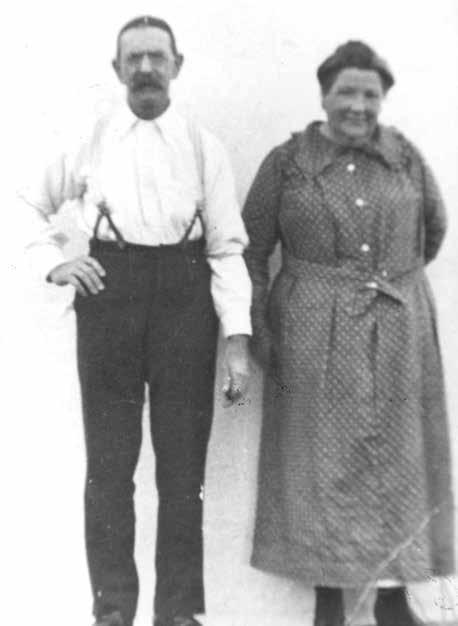

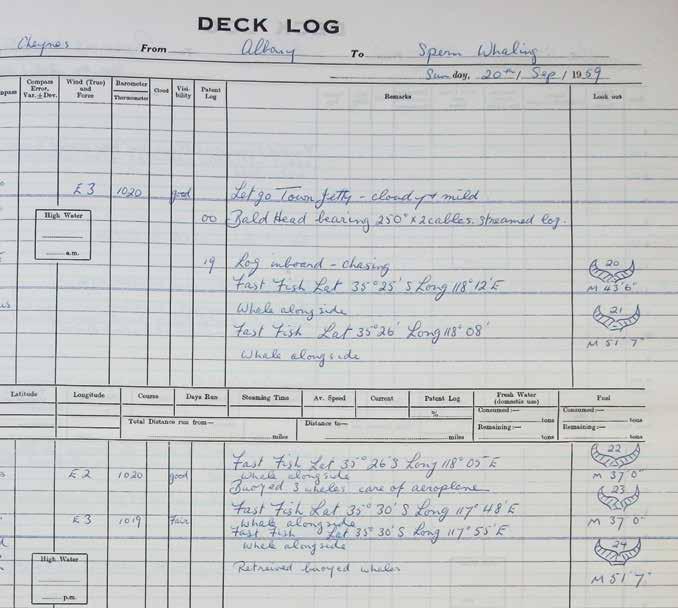

A deck log from the whale chaser Cheynes , from September 1959, records its positions and, in the far right column, details of its catch.

02

Logbooks owned by Discovery Bay Tourism Precinct, WA, chronicle the lives and actions of Norwegian whale chasers.

Images Discovery Bay Tourism Precinct

Past grants have aided the restoration and conservation of significant vessels and helped to develop many exhibitions

01

Maiwar, the boat Tom Robinson designed, built and launched in Peru, and which he was forced to abandon in the eastern Coral Sea. It was later found on the island of Panawina, Papua New Guinea. Tom is recognised by the Guiness Book of Records as the youngest person to row across the Pacific Ocean and is one of the maritime adventurers featured in the Queensland Maritime Museum’s Making Waves exhibition. Image QMM

02

Lisa Blair is another mariner profiled in Making Waves . She was the first woman to sail solo around Antarctica, and she also set the record for its circumnavigation. Image Callum Sherington

This year’s scheme provided $130,000 for dispersal across multiple institutions nationwide. There were 16 successful applicants and 10 training courses were awarded. Three of the projects that received assistance are outlined below.

The Discovery Bay Tourism Precinct was awarded $8,265 to complete their project of translating and digitising logbooks in their possession. These logbooks are key to understanding the history of Discovery Bay. They chronicle the lives and actions of Norwegian whale chasers as they served aboard the steamship Toern Local residents crewed these ships for more than 26 years, and the vessels were significant to the industry and economic development in the area.

The funding will help preserve the books and will allow interpretive imagery of them to be created. The project aims to inform the local community, as well as national and international researchers, of the history of this ship and community, including how the vessels helped facilitate Norwegian migration to and settlement in Australia.

The Queensland Maritime Museum received funding of $12,994 to help develop and create a new exhibition dedicated to significant Australian maritime adventurers, including those who have sailed around Antarctica, rowed across the Atlantic and circumnavigated the globe. This exhibition will remind visitors of the achievements of Australian people and our inescapable connection to the sea. It will illuminate the importance of Australians in maritime sport, recreation and recordsetting, and will educate the public about challenging journeys of ocean exploration, historical lives at sea and maritime technologies such as sail-making and navigational and safety equipment.

Glenelg Shire Council – Portland Maritime Museum, SA: First Nations Gallery

Glenelg Shire Council – Portland Maritime Museum was awarded $14,990 and in-kind support to create a First Nations Gallery focusing on the region’s Gunditjmara people. Co-curated by the local traditional owners’ group, it will tell of their connection to sea country, informing the local community of the Aboriginal presence and stories still present within it. A mural by a Gunditjmara artist will mark the entrance to the exhibition space. The Gunditjmara hold a unique and significant relationship with the sea and especially to whales; a whale skeleton will be central to the exhibition, and other objects will also be displayed.