Bearings

From the Director

WELCOME to our autumn edition – the 150th issue of Signals

We had a wonderfully busy summer – a season of exploration with two James Cameron–related exhibitions, Challenging the Deep and Ultimate Depth – A Journey to the Bottom of the Sea, alongside Ocean Photographer of the Year Challenging the Deep continues its world tour, with its next venue closer to home, in Townsville.

Our new boardwalk became the centre of activity outside the museum, providing a solid base (pun intended) for patrons as they explored our vessels or the Halvorsen Centenary Flotilla or dropped into Ripples for a great coffee.

Ocean Photographer of the Year will conclude on 27 April. It’s really very special and I strongly encourage you to visit. It will be followed by Wildlife Photographer of the Year in mid-May.

We were delighted that Endeavour could be the lead attraction of the Australian Wooden Boat Festival in Hobart in February, and that both legs of the journey to and from Hobart were fully booked. The museum is proud to be a major partner in the festival. Sailing Endeavour remains a priority, and plans are under way for the next voyage.

On the sailing front, Duyfken will recommence its harbour sailing season in March, sailing Fridays and Saturdays. These sails are always very popular, with details and bookings available via the museum’s website.

We recently opened a small exhibition in Wharf 7 entitled Secret Strike – War on our shores. This exhibition features the stern section of the Japanese midget submarine M22 (kindly on loan from the Royal Australian Navy), which took part in the attack on Sydney Harbour in 1942. The exhibition will also feature a range of materials about the strike, including new works by Ken Done. This exhibition, along with a range of other museum initiatives, is being held to mark the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in the Pacific.

And finally, on this our 150th edition, I invite you to make a $150 tax deductible donation (or any amount you choose) to the museum to support our good work. Details can be found at www.sea.museum/donate. Or if you would like to discuss additional ways to support us, please contact the museum’s Foundation at foundation@sea.museum

Wishing you a fabulous 2025.

Daryl Karp AM Director and CEO

The museum’s revamped boardwalk provides extra seating and shade. Image Jasmine Poole/ANMM

Contents

Autumn 2025

Acknowledgment of Country

The Australian National Maritime Museum acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora nation as the traditional custodians of the bamal (earth) and badu (waters) on which we work.

We also acknowledge all traditional custodians of the land and waters throughout Australia and pay our respects to them and their cultures, and to elders past and present.

The words bamal and badu are spoken in the Sydney region’s Eora language. Supplied courtesy of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council.

Cultural warning

People of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander descent should be aware that Signals may contain names, images, video, voices, objects and works of people who are deceased. Signals may also contain links to sites that may use content of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people now deceased.

The museum advises there may be historical language and images that are considered inappropriate today and confronting to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The museum is proud to fly the Australian flag alongside the flags of our Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea Islander communities.

2 A cavalcade of classic craft

Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2025

10 A vibrant achievement

Celebrating 150 issues of Signals

14 A navigator’s last journey

Matthew Flinders returns to his home town

18 Royals by sea

Regal voyages to the ends of the Empire

26 Meet Bikpela Binatang

A hydrothermal chimney dredged from the deep

30 A view from a window

Charmian Clift – ‘an affinity with the sea and ships’

36 Oh! What a lovely war

Prisoners in Arcady

44 The remarkable tale of the Estramina

A colonial Spanish vessel wrecked in Australian waters

52 Adventure Bay

The safe haven on Hobart’s doorstep

60 One free woman

The true story of convict Hannah Rigby

66 Charting a sustainable future

The winners of the 2024 NSW Sustainability Awards

70 Members news and events

Talks and tours this autumn

74 Exhibitions

What’s on show this season

78 Collections

A model of Tu� Do joins the National Maritime Collection

80 National Monument to Migration

A special panel to honour our Vietnamese migrants

82 Foundation news

A new location for T ∙ u� Do

84 Readings

Admiral VAT Smith, father of Australia’s Fleet Air Arm

88 Currents

Prestigious awards for our former curator Lindsey Shaw

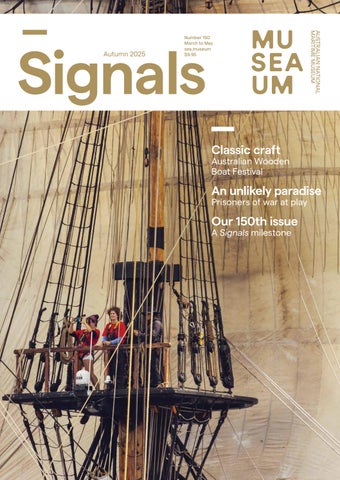

Cover Endeavour in Hobart for the Australian Wooden Boat Festival. Pictured aloft during the opening Parade of Sail are voyage crew members Caroline Kane and Jemima Carey and professional crew member Paula Tinney. Image John Bowen

A drone’s-eye view of some of the vessels that took part in the festival. Image Stuart Gibson/ AWBF

Classic craft converge on Hobart

Australian Wooden Boat Festival 2025

Boats and visitors from near and far gathered in Hobart in February to share stories, skills and knowledge, and celebrate the living history of maritime traditions.

THE AUSTRALIAN WOODEN BOAT FESTIVAL is Tasmania’s largest free event and the biggest celebration of wooden boats and maritime culture in the southern hemisphere. It began in the early 1990s, when three friends had the idea to celebrate and promote their state’s superlative boatbuilding timbers and its tradition of fine shipbuilding. Those aims are still at the heart of the festival, and continue to be enthusiastically embraced by local, interstate and international attendees. This year’s Australian Wooden Boat Festival (AWBF) attracted more than 380 vessels from countries around and beyond the Pacific and an estimated 60,000 participants of all ages.

A Pacific focus

The theme of this year’s festival was the Pacific, and guests from Aotearoa New Zealand, New Caledonia, Hawaii, Tahiti, the Marshall Islands, Japan, the US West Coast and Niue shared their unique maritime stories through captivating demonstrations, interactive workshops and engaging displays. The Pacific Seafarers Precinct offered talks and presentations from esteemed shipwrights, curators and adventurers. Festival-goers were invited to try their hand at traditional art forms such as wood-block rubbings with artist Michel Tuffery and diverse weaving techniques with weavers from Samoa, Niue and Aotearoa New Zealand.

The festival spanned more than 30 venues across the waterfront and into the city and beyond

Cultural institutions from Pacific nations were also represented. The Tino Rawa Trust, founded in 2007, is committed to preserving Aotearoa New Zealand’s classic yacht and launch heritage, and focuses on conserving and restoring historically significant vessels, often employing traditional boatbuilding techniques and materials. The New Zealand Maritime Museum Hui Te Ananuia Tangaroa welcomed visitors to drop in and join the korerō (conversation) to explore the nation’s voyaging history and discuss the ancient art of Pacific navigation, the significance of first encounters and the diverse narratives that have shaped their nation. The Pacific Traditions Society (PTS), founded in 1988 by Dr Marianne (Mimi) George and Dr David Lewis, teaches young people cultural knowledge about the ocean through voyaging, believing that ancient wisdom about the ocean, climate, and biodiversity, developed over millennia of voyaging in Oceania, is crucial for sustainable living and cultural survival.

01 Entertainment offerings included live theatre, roving music performances, captivating exhibitions, a Pacific Film Festival and plenty of active and hands-on activities for families and kids.

Image Michelle Bowen

02

A fine display of smaller craft at Constitution Dock.

Image Ben Cunningham/AWBF

The Australian National Maritime Museum once again sponsored the Wooden Boat Symposium

01

In the Shipwrights Village, festival-goers had the chance to ask questions of expert shipwrights from the Franklin Wooden Boat Centre, chat with current and former students, and even get hands-on experience with traditional tools and Tasmanian timbers.

Image Scarlet English/AWBF

02

The ever-popular Quick ‘n’ Dirty Boatbuilding Challenge tasked young people with building a craft with limited materials and in limited time, then racing it under sail and oar.

Image Michelle Bowen

03

The festival’s Pacific theme drew attendees from New Zealand, New Caledonia, Hawaii, Tahiti, the Marshall Islands, Japan, the US West Coast and Niue.

Image Alex Nicholson/AWBF

The Wooden Boat Symposium

The Australian National Maritime Museum once again sponsored the Wooden Boat Symposium. Over three days and two nights, a distinguished line-up of professionals and passionate enthusiasts shared their expertise, exploring traditional watercraft, Pacific voyaging and maritime history, social and environmental issues within the region, and ambitious restoration projects. ANMM Manager of Indigenous Programs Matt Poll spoke about engaging communities in Indigenous collections research. Former Curator of Historic Vessels David Payne discussed an ANMM research project to document and showcase the sophisticated, functional and beautiful traditional watercraft of Papua New Guinea. Ben Hawke talked of the Pacific of the 1940s to the 1970s through the eyes of his grandfather Jack Earl, a yachtsman and artist who sailed on Maris and the wooden gaff ketch Kathleen Gillett, which is now owned by the museum.

Popular sessions at the symposium concentrated on adventure stories and restoration projects

Other presenters of Pacific themes included Darienne Day, who discussed canoes as vessels of wisdom and how they promote learning through voyaging; Dr Mimi George, who related how an ancient Polynesian voyaging vessel is built and used today as sustainable sea transport; and Alson Kelen and Hoturoa Barclay-Kerr, who spoke of Pacific projects that address social and environmental issues through seafaring.

Other popular sessions concentrated on adventure stories and restoration projects. Tony Stevenson spoke of the ‘South Sea vagabond’ Ngataki, an iconic Depression-era yacht and its adventures that inspired a generation of New Zealanders. Larry Paul discussed the remarkable recovery of the schooner Daring , beached during a storm in 1865 on the west coast of New Zealand’s North Island then buried in sand dunes for 153 years. Leo Goolden detailed the ambitious Tally Ho rebuild that started with a $1 rotten hull and became a crowdfunded YouTube sensation.

01

The Tasmanian Vintage Diving Group demonstrated the art of old-style diving with authentic gear.

Image Ben Cunningham/AWBF

02

A Tasmanian ningher, or rolled-bark canoe, was an appropriate vessel for a row around Constitution Dock.

Image Michelle Bowen

03

Endeavour and James Craig in the Parade of Sail, the traditional start to every festival, in which participating vessels sail together up the Derwent River then congregate at Constitution Dock. Image Michelle Bowen

Traditional skills

The preservation and promotion of traditional maritime skills have always been a cornerstone of the festival. The Shipwrights Village is one of its major attractions, offering a first-hand look at the craftsmanship behind wooden boat building. Live demonstrations showcased time-honoured skills like caulking, roving, rope work and figurehead sculpting, while festival-goers could see boats built on site, explore the materials and techniques that have shaped this craft for centuries, and try their hand at various skills.

Multi-day workshops on and off site catered for those who wished to delve more deeply into a particular skill. Under the tutelage of master craftspeople, participants could make a hollow wooden surfboard or wooden handboard for bodysurfing, try their hand at Japanese joinery and wood crafts, create a boat fender or traditional ocean plait mat from rope, or be introduced to the tools and techniques of turning wood on a traditional foot-operated spring pole lathe.

A wide reach

While the festival centred on boats and Hobart’s waterfront, it spanned more than 30 venues across and beyond the city, providing exposure and a commercial outlet for artists, craftspeople, stallholders, food and beverage providers and varied community interest groups.

Biennially, the AWBF injects around $4 million directly into the wooden boat industry and its supporters. The ripple effect generates a further $25 million for tourism and the local economy. The festival’s success is made possible by the dedication of over 400 volunteers, whose tireless efforts ensured the seamless operation of this world-class event.

AWBF General Manager and Festival Director Paul Stephanus said:

AWBF is Tasmania’s most beloved festival, driven by passionate individuals and community groups dedicated to preserving our maritime heritage. While some may view it as a niche event for wooden boat enthusiasts, they’d be mistaken. This is a celebration for all, uniting our community and visitors to share in the craftsmanship, joy, and stories that make this event truly special.

Compiled by Signals editor Janine Flew from materials provided by the Australian Wooden Boat Festival.

A vibrant achievement

Celebrating 150 issues of our flagship publication

FEW MAGAZINES CAN CLAIM the healthy longevity that Signals enjoys. As the museum’s flagship publication, even its name has stood the test of time!

Well before the Australian National Maritime Museum opened its doors to the public, in 1986 a rather slim ANMM Newsletter was instigated to keep our stakeholders up to date. Editing this periodical was soon passed to public affairs officer Jeffrey Mellefont, who conceived a bigger vision and a bold new title. In 1989 he launched Signals, ‘to flag that this would be the very model of a modern maritime museum’.

And so it has been. Signals reported on the museum’s opening in 1991, plus our anniversaries over three subsequent decades. We have boasted visits by prime ministers and presidents, rock stars and sporting legends, ambassadors and performers, artists and seals (yes, seals).

‘Signals gives the museum’s people a vibrant medium to present their work to a wider, general readership,’ enthuses Jeffrey.

‘It welcomes everyone into our fascinating world of maritime and naval histories, cultures and heritage.’ From the outset, the magazine has introduced audiences to the foundations of our institution: volunteers, staff, exhibitions, collections, programs, research and – of course – vessels.

The evolving design of Signals , from a four-page newsletter to today’s quarterly of 80 or more pages.

Image Jasmine Poole/ ANMM

A perk of editing Signals is publishing articles on your particular areas of interest. For founding editor Jeffrey Mellefont, it was Indonesian seafaring history and culture; for current editor Janine Flew, it’s textile arts, ceramics and natural history. Image Jasmine Poole/ANMM

The museum’s fleet looms large across 150 editions. Pride of place goes to Endeavour, from the building of the replica in Perth, to reportage of its global voyages, then the exultant day when this tall ship came to call Sydney its home port. Readers have learned of the bark’s history, construction, crew, character and quirks. This issue is no exception, with Endeavour sailing home from Hobart as we go to press. Duyfken has likewise graced these pages, alongside cameos from the entire fleet, from diminutive Thistle to the grey bulk of HMAS Vampire.

But more than anything, diversity is the key to the ongoing success of the magazine.

‘I first started reading Signals back in 2002,’ recalls Randi Svensen, ‘and was immediately drawn to the variety and quality of the articles, many of which introduced me to new and fascinating subjects’. Randi subsequently became a regular contributor, sharing her expertise from Halvorsens to tugboats, obituaries to recollections. Behind the scenes, Randi is also the magazine’s longtime proofreader, eyeing off accuracy and expression. She has also taken the helm several times to edit entire issues. ‘It was a daunting prospect but also very exciting,’ she recalls, ‘even if sometimes it felt as if I were trying to juggle one too many balls!’

Signals has taken readers into the depths of the museum, from the conservation laboratory to kids’ programming, yet it also looks outwards. We regularly feature new craft added to the Australian Register of Historic Vessels, as well as stories on colleagues around the country who participate in the Maritime Museums of Australia Project Support Scheme. Then there have been the nawi-building workshops on Sydney Harbour, as well as visiting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities on Country. Our maritime archaeology team has regularly showcased wreck sites from around the world, from Gallipoli to Papua New Guinea, Indonesia to Victor Harbor, Rhode Island to the South China Sea.

Shipwrecks have unsurprisingly surfaced with regularity, especially Australia’s first two submarines, AE1 and AE2 Signals furthermore affirms that Australia is a maritime nation in the Indo-Pacific region, sharing the watercraft traditions and cultures of our near neighbours. That embrace of global journeys and stories has also characterised the many features from the Welcome Wall – our National Monument to Migration. Add in maritime arts and stunning photography, and there’s never any shortage of variety.

‘Turning that into a magazine each quarter is always a pleasure,’ says Jo Kaupe, who with her partner Jeremy Austen has designed Signals from number 82 in 2008. ‘Since that first issue, we’ve mainly worked with two great editors, Jeffrey and Janine. As we’re Jo and Jeremy, we make up what we call the “J-Team”,’ she adds. It’s a slick operation, with Jeffrey Mellefont handing over the reins to the current editor, Janine Flew, after delivering issue 104. ‘As soon as I saw this job advertised in 2012, I knew it had my name all over it,’ says Janine. ‘I grew up around boats, I’ve sailed competitively and I enjoy the challenge of making each issue unique and relevant.’

When I came to the museum in 2021, my proudest moment was knowing that Signals was a key responsibility within my faintly comical job title of ‘Head of Knowledge’ (just add ‘Big’ in front of it!). Having already published in Signals myself, I was aware of the high standards expected for research and expression, as well as the magazine’s immersion in the vibrant fields of maritime history and heritage. This is a place to publish exciting new finds, fresh interpretations of established stories, the exuberance of acquiring objects for the National Maritime Collection, or insights about how our exhibitions come together. No wonder we have attracted impressive research from Jeffrey and Randi, as well as our past and present curatorial team, including Dr Nigel Erskine, Dr James Hunter, Dr Stephen Gapps, Emily Jateff, Kim Tao, Kieran Hosty, Dr Roland Leikauf and Inger Sheil.

So where to from here? We are brimming with ideas, including more about our rivers and lakes, the visceral pleasures of sailing and diving, and the aquatic pursuits that unite Australians, from fishing to surfing. There are also many communities we want to visit, from the River Murray to Channel Country – and Antarctica! But most of all we want you – our readers – to tell us what will keep you turning the pages of Signals for another 150 issues.

Dr Peter Hobbins is the museum’s Head of Knowledge. His job title still makes him chuckle.

To share your suggestions for the future of Signals , please write to the editor at publications@sea.museum

A navigator’s last journey

Bringing Matthew Flinders home

More than 200 years after he died, explorer Matthew Flinders has been laid to rest in his home town in Lincolnshire, UK. By Margie Brophy of the Bass and Flinders Maritime Centre in George Town, Tasmania.

ON 13 JULY LAST YEAR I was fortunate enough to be a part of history being made. I attended the reburial of Matthew Flinders in Donington, Lincolnshire, UK. How could this be possible, you might ask, when he died in 1814? Matthew Flinders was originally buried in the churchyard of St James, Piccadilly, but as the city grew, Euston Station was built on top. People knew he was there, but was he under platform 4 or platform 7? In 2019, as a new line of the London Underground was being created, archaeologists dug the site and, among the 60,000 graves, found Matthew Flinders’ coffin. It had a lead breastplate on top with the words ‘Captain Matthew Flinders RN died 19th July 1814 Age 40 years’.

A committee, called Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home, was formed in Flinders’ home town of Donington to organise a reinterment service and celebrate his life. When we arrived in July, the village was decked out in style, with window displays and flowers and flags from both Australia and the UK lining the streets. We arrived a couple of days early so we could meet with schoolchildren and chat with locals. Everyone was very welcoming –in fact, local people couldn’t believe we had come from the other side of the world to take part. The Bass and Flinders Maritime Centre in George Town, Tasmania, had established an initial relationship with the village back in March, when we cut two birthday cakes simultaneously – one at the centre and another in Donington – to celebrate Flinders’ 250th birthday.

Matthew Flinders was originally buried in the churchyard of St James, Piccadilly, but as the city grew, Euston Station was built on top

Matthew Flinders’ coffin being lowered into the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood, Donington. Image Stephen Daniels

The Hon Nick Duigan MLC gave us a Tasmanian flag to present to the committee, and it is now proudly hanging in the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood next to the stained-glass window commemorating Matthew Flinders, George Bass and Joseph Banks.

The day arrived with sunshine and church bells. Crowds gathered as we were interviewed by BBC, ITV and Lincolnshire Independent. There was a real buzz as officials assembled at the church and service people lined the streets. The Bishop of Lincoln Cathedral, The Right Rev Dr David Court, led the procession, followed by The Hon Frances Adamson AC, Governor of South Australia; mayors and deputy mayors from Lincoln and Boston, in the UK, and Port Lincoln, South Australia; the Australian Deputy High Commissioner, Elisabeth Bowes; and naval officers, including Dr (Capt) Peter Martin from Hobart. The flag draped over the coffin was half British and half Australian, to represent the strong links between the two countries.

After the coffin was lowered into the grave inside the church, sand from three different beaches in South Australia was poured in, along with soil from London and Donington. Laurie Bimson represented Bungaree, the Eora man who circumnavigated Australia with Matthew Flinders. Into the grave Laurie placed a boomerang engraved with a stingray, Bungaree’s totem, and the choir sang Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’ with special additional verses about Flinders.

Later, descendants Susie Flinders-Beatty and Rachel Flinders-Lewis presented the breastplate from the original coffin to the South Australian governor to be taken to South Australia for touring and display purposes. We hope one day to have an opportunity to bring the breastplate to Tasmania.

Finally, a marble grave ledger will be placed over the grave, recording Matthew Flinders’ voyages – including his circumnavigations of Tasmania and Australia –and depicting his beloved cat Trim draped over the top.

The flag draped over the coffin was half British and half Australian, to represent the strong links between the two countries

Luckily, the marble carver’s father in-law is Tasmanian and mentioned, ‘Whatever you do, don’t miss King and Flinders islands off the map!’, and I’m pleased to say they are both there.

It was an amazing opportunity to be present, along with volunteers Vince Brophy, and also Craig Dixon and Tom O’Byrne, who helped to build the replica of Flinders’ boat Norfolk and sail its replica voyages. Craig said that for him:

This is such a highlight after having been involved with the replica Norfolk for 30 years. It’s just a shame Bern Cuthbertson [who re-enacted all of Norfolk’s journeys in the replica vessel] wasn’t around to enjoy it as well.

Now we feel an extra link to our replica Norfolk here at the Bass and Flinders Maritime Centre in George Town. Why not come for a visit yourself? We’d be delighted to tell you more stories.

bassandflindersmuseum.com.au

01

Craig Dixon and Margie Brophy, from the Bass and Flinders Museum in George Town, Tasmania, being filmed by the BBC. Images Vince Brophy unless otherwise stated

02

Her Excellency the Hon Frances Adamson AC , Governor of South Australia, and other dignitaries enter the Church of St Mary and the Holy Rood for the reinterment service.

03

The coffin plate from Flinders’ original grave, which was uncovered in 2019 under Euston Station in London, and has now been presented to South Australia. Image Flinders University

04

Craig Dixon inside the church with a Tasmanian flag presented by the Tasmanian visitors to the Matthew Flinders Bring Him Home Committee. The stained glass window commemorates Flinders (centre), Joseph Banks and George Bass.

Royals by sea

Regal voyages to the ends of the Empire

While indexing ships’ postcards for the Vaughan Evans Library, Janet Halliday learnt that HMS Ophir carried royalty here in 1901. In a search for other royals who have visited Australia by sea, she found voyages that took months or even years, and which were marked by woeful organisation, protests, chaos, fatalities and even an assassination attempt.

Prince Alfred, second son of Queen Victoria, was the first royal to visit Australia. He arrived as the 23-year-old commander of HMS Galatea, here depicted in Sydney Harbour (left foreground). Hand-coloured print from The Illustrated London News , 11 April 1868. ANMM Collection 00039567

It was time to show the colonies that the Crown and Mother England loved their family

BRITANNIA FAMOUSLY RULED THE WAVES – and, until 1901, it also ruled Australia. Although pleased to call us part of their empire, for the first 79 years after colonising the country no member of the royal house graced our shores. That changed in 1867, when Queen Victoria sent one of her sons, Prince Alfred. There were only five more such visits over the next 87 years, and the first visit by a monarch wasn’t until 1954. All these trips were by sea. The last 70 years have seen more than 50 royal tours, but the old imperial and leisurely appearances have become more businesslike, shorter – and by air.

The second son of Queen Victoria, Prince Alfred had been in the navy since he was 12, and at the age of 23 was commander of HMS Galatea, a 3,500-ton, 26-gun, wooden screw frigate. Ordered to take the ship on a world tour, including India and New Zealand, he arrived in Melbourne in 1867. It was time to show the colonies that the Crown and Mother England loved their family. Alfred’s instructions were vague and the planning of his tour was woeful. In Queensland there were far too many engagements and even poor accommodation, which annoyed the prince. In capital cities, elaborate archways festooned the main streets and people were enthusiastic about the visit, but disaster followed disaster. Three boys climbed up on a procession float depicting the Galatea and set off fireworks that caused a fire, killing them.

A planned ball had to be cancelled because the hall burned down. Alfred attended what was supposed to be a loyal welcome, but which was embarrassingly disrupted by violent protests outside. Noisy Irish republican songs were sung and a boy died in the melée. When a free public banquet on the Yarra River attracted 40,000 people instead of the expected 10,000, Alfred cancelled his visit, annoying the crowd and resulting in mayhem. The tumult was fortified by a wine fountain supplied from a 500-gallon (2,200-litre) cask.

Sydney did its best to outdo Melbourne, with its own archways and fulsome declarations of loyalty, but did not manage to improve on security. The prince was shot by James O’Farrell at a picnic held at Clontarf. He spent a few weeks recovering at Government House, but the New Zealand tour was cancelled and Alfred sailed home.

In 1881 Prince Albert, aged 17, and Prince George, aged 15 (later George V), were sent on a three-year worldwide cruise on HMS Bacchante, on which they were both midshipmen. But Queen Victoria was worried that the vessel might sink and her grandsons drown, so before the boys joined the ship, Bacchante was sent out in a gale to prove itself fit for the task. A 4,070-ton iron-clad corvette with a crew of 450, Bacchante was screw-propelled and armed with muzzle-loading guns, torpedo carriages and machine guns.

The teenaged princes were expected to fulfil two roles –to be both young midshipmen and royal ambassadors 02

As the princes were part of the ship’s company, some restraint was supposed to be put on their activities. Their tutor accompanied them to keep them in check, and their shipboard activities were treated as part of their education. It was presumed that activities on land would be a holiday for them. Not so. Yet again, civic leaders paid little attention to planning and almost no heed of the boys’ youth. Local worthies exhausted the princes with the many balls, dinners, receptions, foundation stones and loyal addresses. By the time they arrived in New South Wales, the boys had had enough.

A big part of the problem was that they were expected to fulfill two roles – to be both young midshipmen and royal ambassadors. On the morning they arrived in Sydney, for example, they faced the ordeal of a practical navigation examination paper, after which they had an appointment to visit the governor. Too late, it was realised that the boys were tired and couldn’t manage everything on their program. People were peeved. The princes’ own thoughts on the matter are not recorded. They were required to keep a diary, but this consists almost entirely of tactful descriptions of what they had seen.

In 1901 things improved with a visit by the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York. The duke was Prince George, who had been aboard Bacchante; he and his duchess later became King George V and Queen Mary.

01

Sketches of life on board HMS Bacchante, from The Graphic, 20 September 1879, pages 288–9.

02

Prince Albert Victor (left) and Prince George of Wales dressed in mining rig. From their account of their voyage, The Cruise of HMS Bacchante 1879–1882, Vol 1, page 512.

What was supposed to be a loyal welcome was embarrassingly disrupted by violent protests outside

By today’s standards the speeches were long winded and some activities would not now be countenanced

Unlike the first two royal tours, this one was not on a naval vessel, but rather an Orient Line passenger ship commissioned as a royal yacht: the HMS Ophir of 6,910 tons. The visit was much better planned, though by today’s standards the speeches were long winded and some activities would not now be countenanced by the royal person or the public. The focus was to give a royal presence to the opening of the first Federal Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia in Melbourne. Civic leaders were, of course, to the fore. In Sydney, where a reception was held for the duke, he was required to shake hands with all and hear addresses by no fewer than 24 corporate bodies. The duke and duchess were given a very enthusiastic welcome in Melbourne, as was the crew. Illuminated shops and specially built arches contrasted favourably with Sydney’s meagre decorations and small crowds. Sydney was also viewed disparagingly by a crewman, who thought it badly paved, with narrow streets. Much admired, however, were the Australian ships in the harbour displaying a waterfall of fireworks cascading from their upper decks into the water. The royal couple’s reception in Sydney might have been lacklustre, but people were probably jaded, having just celebrated the Commonwealth inauguration. Much bigger crowds turned out to farewell the couple.

After World War I, George V thought that Australia should be thanked for its part in the conflict, so Edward, Prince of Wales, was sent off in HMS Renown in 1920, accompanied by the young Lord Louis Mountbatten. Edward appears to have accomplished this task with considerable enthusiasm. At the equator he was the target of elaborate ‘crossing the line’ ceremonies, part of long-hallowed naval tradition. King Neptune came aboard at 9 am, and lengthy poems were recited with gusto by participants, including Edward. The jollity continued until early next morning.

01

The Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) being tossed into Ophir ’s pool as part of a ‘crossing the line’ ritual, as recorded by Harry Price in his account of the voyage.

02

The image that started the author on her search of royal visits by sea: a postcard of HMS Ophir, from the Roy Fernandez postcard collection in the museum’s Vaughan Evans Library –part of his larger collection donated in October 2017.

In many ways these ocean voyages were a holiday for the royals, as long as they were not part of the ship’s crew. Inevitably, however, all endured a very hectic round of engagements once they arrived in Australia. There was also much gift-giving.

Gifts, not always very suitable, have always been presented to royal visitors. The Prince of Wales’ views are unknown, but one wonders whose idea it was to give him a pair of yellow silk pyjamas, made by girls who had each contributed one stitch. When the Duke and Duchess of York (later George VI and Queen Elizabeth) also came on Renown seven years later to open the provisional Parliament House in Canberra, they were given canaries, parrots, parakeets, ‘flying squirrels’ (probably sugar gliders) and a pair of wallabies. The menagerie only gave Renown ’s crew extra work.

Another of George V’s sons, Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester, arrived in Australia in 1934 on HMS Sussex A County class heavy cruiser of 13,315 tons, the ship carried plenty of armament and a crew of 650.

The visit of 67 days included kangaroo hunts, but its main purpose was to open celebrations of the centenary of Victoria. At Ballarat Henry was given a gift that few would sneeze at: three gold ingots, one of which he later gave to his cousin, the young Princess Elizabeth. In Sydney he became the first British royal to attend a surf carnival. In early 1945 he came again, this time as Governor-General. As it was still wartime, he and his family travelled in a blacked-out passenger liner.

Queen Elizabeth travelled by sea to Australia in the 1950s, as did thousands of non-regal passengers over the years. Many made the voyage aboard RMS Otranto, an ocean liner that plied the route between England and Australia. This printed menu card from 1956 is the last of a series of six featuring queens of England. ANMM Collection

ANMS0497[031] © P&O Heritage

02

SS Gothic docked at Circular Quay, Sydney, during the 1954 royal tour of Queen Elizabeth II. Image NSW State Archives NRS-21689-2-5-GPO2_05211

The royal visit by Queen Elizabeth II in 1954 was a blockbuster –the first by a reigning monarch

The next royal visit was in 1954, and it was a blockbuster – the first by a reigning monarch, Queen Elizabeth II.

For what was to be the last royal visit made by sea, no expense was spared. The ship, the SS Gothic of 15,902 tons, was escorted in our waters by two Australian naval ships. Gothic had been painted white and extensively refitted, especially its accommodation. Extra radio equipment was installed to meet the demands of state, navy and the press. There were also three BBC entertainment programs available on board, together with recording facilities.

The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh joined the ship in Jamaica with a huge entourage: two ladies in waiting, three private secretaries, one press secretary, one Acting Master of the Household, two equerries, 20 officials and staff, 72 naval staff, nine members of the press and a band of the Royal Marines. There was also eight tons of baggage.

The royal party visited 57 towns and cities in the 58 days they were in Australia. It must have been exhausting and repetitious, but the enthusiasm of the crowds was enormous everywhere. In Sydney hundreds of boats were lined up in the harbour as Gothic arrived, and over half a million people gathered on the foreshores.

And, at last, the planning was meticulous. Very detailed communications, maps and diagrams were created –for welcomes at government houses, parliament houses, town halls, airports and railway stations. Children were not forgotten. Many thousands were gathered in cities to wave as the Queen drove past at about 30 kilometres per hour. Adelaide and Melbourne held pageants with children spelling out the words ‘loyalty’ and ‘welcome’. In Sydney 120,000 children sweltered for hours in the heat at Centennial Park and the Sydney Cricket Ground, including this author.

The heyday of the empire, when Britain ruled the waves, had long passed by 1954, but very strong links remained between Commonwealth and Crown. Times have now changed. The House of Windsor still wants to retain what’s left of the British Commonwealth, and royal visits demonstrate this soft diplomacy as they have always done. Television coverage enlarges their audience but has dulled the excitement. There have been so many royal visits since 1954 that the mystique has faded. Visits are now streamlined, much shorter – with no holiday cruises on route – and are usually clearly focused on a particular event, after which the royal personage gets on a plane and is back at the palace in less than a day.

Janet Halliday volunteers in the museum’s Vaughan Evans Library. She formerly owned a boat in Europe and spent a year living on board, exploring canals and rivers in The Netherlands, Belgium and France.

Catt, Emily, ‘The 1954 royal tour’ (blog post). National Archives of Australia <https://www.naa.gov.au/blog/1954-royal-tour>.

Crossing the Line with HRH the Prince of Wales in HMS Renown , Friday–Saturday April 16-17, 1920. No author but ‘by authority’. Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1920.

With the ‘Renown’ in Australasia: the magazine of HMS Renown , December 1919 to October 1920. Australasian Publishing Co Ltd, Melbourne, no date. Vaughan Evans Library 910.45 WIT

Maritime Radio, ‘1953–54: SS Gothic as a royal yacht’ <https://maritimeradio.org/ship-stations/gothic-mauq/1953-1954royal-yacht/>.

Nautilus International, ‘Gothic’ <https://www.nautilusint.org/en/newsinsight/ships-of-the-past/2022/june/gothic/>

Pike, Phillip W, The Royal Presence in Australia 1867–1986 Royal Publishing, Adelaide, 1986.

Price, Petty Officer Harry, The Royal Tour: Or the cruise of HMS Ophir being a lower deck account of their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York’s voyage around the British Empire, 1901. Webb & Brown, Exeter, 1980. Vaughan Evans Library 910.09171241 PR. Price’s handwritten journal is full of his honest appraisals and watercolour paintings.

The Cruise of Her Majesty’s ship Bacchante , 1879–1882. Compiled from the private journals, letters, and notebooks of Prince Albert Victor and Prince George of Wales, with additions by John N Dalton. Vaughan Evans Library call number 910.45 CRU

Wallace, Sir Donald Mackenzie, The Web of Empire: A diary of the imperial tour of Their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York in 1901. Macmillan, London, 1903.

The chimney was carefully craned into place as a keystone object in the new exhibition Ultimate Depth: A Journey to the Bottom of the Sea

Meet Bikpela Binatang

A hydrothermal chimney dredged from the deep

The deepest reaches of our oceans are little known to science and difficult to study. A chance and extremely rare find 25 years ago – a huge hydrothermal chimney –is now a feature of our new exhibition Ultimate Depth: A Journey to the Bottom of the Sea, writes Emily Jateff.

TWO YEARS AGO, I was on board SY Ena for a VIP cruise associated with the inaugural Ocean Business Leaders Summit. There I met Professor Elaine Baker from the University of Sydney. Professor Baker told me a story about a hydrothermal chimney that had been recovered intact during a CSIRO voyage a couple of decades ago. While she wasn’t sure where it ended up, my interest was piqued.

Hydrothermal vent communities are usually found near volcanically or geologically active sites. Hydrothermal chimneys are formed when seawater seeps through holes in the earth’s crust and meets superheated magma. The collision of hot and cold pushes up the crust and shoots boiling seawater infused with minerals and chemicals back into the ocean. Living on the sides of and around hydrothermal chimneys are thousands of microbes that harvest energy from the chemicals and minerals spewed by the chimney in a process called chemosynthesis. It should be impossible for anything to survive here. Yet hydrothermal vent sites support life not only on and around the chimney structures, but even beneath the surrounding volcanic crust.

Jumping forward to 2024, I was hard at work on a new exhibition investigating the five zones of the ocean. While we have several objects in our collection that relate to the upper levels of the ocean (up to 1,000 metres depth),

and we knew we were getting the DEEPSEA CHALLENGER submersible to illustrate the hadal zone (6,000–10,000 metres), I had very little to show that anything lived in the abyssal zone (4,000–6,000 metres). A hydrothermal chimney would be perfect.

Fragments of hydrothermal chimneys are rare, and complete specimens are hardly ever recovered. I knew of only one other full cross-section on display in a museum worldwide – a partial chimney vent held by Museums Victoria on permanent display. However, it was not available for loan. Where was the other half? Then I remembered Professor Baker’s story.

Enter Dr Joanna Parr, Executive Manager, Operations at the CSIRO–Kensington Australian Resources Research Centre (ARRC) in Perth, Western Australia, where the other half has been on display in the foyer since its recovery in 2000. Dr Parr and the CSIRO generously facilitated assessment of the chimney by museum conservation staff and, after throwing it a farewell party, allowed it to travel back across the country to share its story with the public. In November 2024, it returned to Sydney for the first time in 24 years, and was carefully craned into place as the keystone object of the abyssal zone in the new exhibition Ultimate Depth: A Journey to the Bottom of the Sea

Hydrothermal vent communities are usually found near volcanically or geologically active sites

01 Active sulfide chimneys in the Bismarck Sea, Papua New Guinea, at an average depth of 1,640–1,740 metres.

02 Where it broke at the base, the chimney was brightly coloured and stained, with fragments of glassy volcanic rock indicating that the entire structure was recovered intact.

Images courtesy Dr Ray Binns/ CSIRO

Dr Parr also introduced me to Dr Ray Binns, who was chief scientist on board the CSIRO research vessel Franklin voyage to Manus Basin, Papua New Guinea, in 2000, when the hydrothermal chimney was recovered. At the time, the Australian government was investigating the option of mining hydrothermal vent fields to extract the valuable minerals they contain, particularly those with 10–20 per cent copper and high amounts of gold.

In his cruise report, Dr Binns records the find:

Tuesday 25th April 2000, Day 12 (Anzac Day), extract from daily narrative (amended):

Dredge MD-133 deployed after nightfall to sample microbes from active chimneys in the Roman Ruins hydrothermal vent site. On hauling, the dredge immediately became anchored. It was freed after 50 minutes, and on emerging from the water in darkness a giant chimney was precariously balanced across the ring of the dredge. It was quickly and carefully brought inboard. The chimney specimen, which we named Bikpela Binatang (Big Bug in Tok Pisin [a language of Papua New Guinea] ) was a tapered cylinder 2.7 metres long, 2.0 m in circumference at the base and 1.3 m at the top. Its weight, estimated at 800 kg, was later measured at RAAF Darwin as 970 kg.

Bikpela was a little different from the usual type of sulfide chimney as it is relatively low in sulfide minerals, containing more berite and silica with a thin black manganese oxide crust partly dislodged by handling. It contained significant gold, silver and zinc, but was low overall in copper and lead. The basal fracture on which the chimney broke was brightly coloured with orangered and yellowish iron oxide staining, and possessed fragments of glassy volcanic rock indicating the chimney was basically torn out by its roots.

Microbe samples were taken from many locations on the chimney, and also from its interior using a cordless electric drill. Fluid dripping from the chimney on recovery was sampled for microbes and geochemistry. Its acidity indicated the structure was active when recovered. Small pieces of stained dacite, several live gastropods (slugs and snails) and some galatheids (crustaceans) were also present in the chain bag of the dredge.

On return to port in Darwin, the Royal Australian Air Force provided air transport of the chimney from Darwin to CSIRO’s Sydney laboratories, after which it was trucked to Perth and sawn lengthwise by David Vaughan (Common Ore Pty Ltd, Western Australia). The smaller part was donated to Museums Victoria, and the larger piece stayed with CSIRO.

And that’s the story of the hydrothermal chimney Bikpela Binatang so far, now on display in our exhibition Ultimate Depth: A Journey to the Bottom of the Sea Come see it for yourself.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Dr Ray Binns for his generosity in sharing his notes, images and expertise. Getting a large object across the country and into an exhibition on a tight timeline is a lot to ask in the museum world. For their help with this, I would like to thank Dr Joanna Parr, Professor Elaine Baker, Rheanon Thornton, Alayne Alvis, Cameron Mclean, Rhondda Orchard, Agata Rostek-Robek, Sally Fletcher and Peter Hobbins.

References

Binns, RA. CSIRO Exploration and Mining, Investigation Report Number P2005/227, Cruise Summary, R/V Franklin FR03/00, Binatang-2000 Cruise, Manus Basin PNG

Binns, RA. 2014, ‘Bikpela: A large siliceous chimney from the PACMANUS Hydrothermal Field, Manus Basin, Papua New Guinea’, Economic Geology vol 109, pp 2243–59.

Emily Jateff is the museum’s Curator of Ocean Science and Technology.

A view from a window

Charmian Clift – ‘an affinity with the sea and ships’

Charmian Clift (30 August 1923–8 July 1969) was Australia’s foremost essayist of the 1960s, publishing more than 200 pieces in the Melbourne Herald and The Sydney Morning Herald. She also published two travel memoirs and two novels, and co-authored many others with her husband, George Johnston. In 1964 Charmian returned to Australia with her family, after ten years living and writing on the Greek islands of Hydra and Kalymnos. They first settled in Mosman with a window view that inspired this essay, which was published in The Sydney Morning Herald on 25 March 1965.

ON THE WINDOW LEDGE in front of my work table stands a shipwright’s model of an Aegean cargo caique. It was made about a century ago by a man named Stephanos, a shipbuilder of Hydra –which is an island of some maritime distinction in the Mediterranean.

The original paintwork of the model has long since faded to nondescript – the sort of bleached and weathered look a working boat wears at the end of a long journey – and some of the planks have splintered slightly, but its shape is beautiful, round-bellied and wide like a split melon, and its detail is a marvel.

Through the hand-carved blocks and the faithful intricacies of the Aegean rig I look out across the sea. Australian waters, not Mediterranean. But the model does not look alien. It sits well against its background.

Here too there is an affinity with the sea and ships. Not perhaps in that intimate friendly backyard sense that belongs to home waters studded with islands, where all communication, trading, and transport depend upon the familiar little boats that are known individually to everybody. It is all on a grander scale here – ships and seas, distances, dangers. More total, in a way.

‘considerably more than half the country’s population lives in sight of an ocean or within reach of one’

Sydney Harbour by James R Jackson was painted in 1965, the same year in which this essay by Charmian Clift was first published. It depicts a scene that would have been very familiar to Clift, looking across Taylors Bay to Rose Bay and Point Piper. Oil on canvas, Mosman Art Collection, donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program by Neil Balnaves AO, 2011. Image Tim Connolly courtesy Mosman Art Gallery and © the artist

There are nearly three million square miles of land enclosed within this enormous freehand scrawl that describes the continuous coast of our country – three million square miles with no seas at all and scarcely even a lake worth speaking of. On the face of it we would not seem to be entitled to much of a nautical heritage, but the fact remains that every one of our biggest cities dips her skirts in the sea, as if for reassurance, and considerably more than half the country’s population lives in sight of an ocean or within reach of one.

For all our great open spaces our touchstone is the sea. Sydney’s harbour seethes with maritime traffic. Melbourne’s suburbs look out on cargoes of lives and freight negotiating the South Channel. In Brisbane, as in Sydney, and Melbourne, masts and derricks and coloured smokestacks make brave romantic cul-desacs of city streets. Millions of urban dwellers have an easy acquaintanceship with things like Gellibrand and Pinchgut and buoys and beacons and channel markers and leading lights and the busy fuss of tugs. And with waterfront pubs with ship prints on the walls, and tide tables, and tattooed men drinking beer. Conrad’s world, this. Stevenson’s world. Still recognisably there.

At weekends and holidays the rigging of my old Aegean caique rules angles across casual blue acres of pageantry that I would not exchange as a spectacle for the Field of the Cloth of Gold. Hundreds of white sails skimming, hundreds of heraldic spinners curved taut and blazoned before the wind. They form and reform in changing patterns, bunch together, stream out in procession, swoop and challenge and leap forward in single pride. Beyond the visual delight one feels such pleasure in order and discipline, in the fine austerity that underlies the airiest things.

And all the time through this gadfly carnival commerce moves with deliberation and dignity, more soberly heraldic but displaying its own precise designations, which I am learning to recognise now. A black stack with two blue bands is Norwegian and its name begins with a ‘T’. Grey hull with red and black stack, and that must be Port Something-or-other, although the ships called City of Something-or-other belong to Ellerman and Bucknall and you know them by their yellow, white, and black. I’ve learned to pick the ‘Marus’ and to tell a tanker from an ore boat, and to know that a Blue Star ship has a ‘Star’ in its name and signifies chilled beef. I’ve learned the Union green, the Orient yellow, the British-India black. And that a Blue Funnel liner means good luck. This is enchantment.

It is more than that, of course. It is for me a re-learning, or re-appreciation, of a traditional sense of isolation. In spite of all the marvels of modern communication one is conscious here of distance – vast distance – and of a bred-in-the-bone dependence upon ships that cannot easily be discarded.

It is not really so very long ago that ships were our only link with the rest of the world. Before the invention of radio and submarine cable the only news Australia had, or could have, of ‘outside’ came by ship, a month old, three months old, six months old, happenings already remote in time as in space. How weirdly opaque the rest of the world must have seemed then. (Even when my husband was a young shipping reporter there was still, he says, this tremendous sense of urgency and excitement in going out with the pilot to board the incoming liners and hear the news of Europe by word of mouth. As if it might be more credible that way.)

Darling Harbour and Pyrmont Bridge, David Moore, c 1948.

‘Sydney’s harbour seethes with maritime traffic’, Charmian Clift notes in this essay. The area depicted here now includes the site of the Australian National Maritime Museum. ANMM Collection 00018900

‘In Brisbane, as in Sydney, and Melbourne, masts and derricks and coloured smokestacks make brave romantic cul-de-sacs of city streets’

‘For all our great open spaces our touchstone is the sea’

All our history has a seasoning of ocean salt. One pretty reminder of this is in the iron-lace balconies and grillwork and railings that have lately been rediscovered as decorative treasure. Ironware junked from the cottages of early Victorian England and shipped out here as ballast for clipper ships coming out to race home again with the wool clip. As ballast it was junked again and grabbed by builders poverty-stricken of materials. It is charming, I think, that the junked ballast from the golden days of sail should be now so high chic.

One can be carried away by this sort of thing. Sail. Clipper ships. Grain races. Sometimes, looking out through the rigging of Stephanos’ caique and across the moving blue miles that darken imperceptibly towards the rim of the horizon, it seems that the merest blink of intent might really reveal the ghosts that still haunt these waters. The immigrant packets with their topsails backed, hove-to for the pilot – the Blackwall and the Kent and the Windsor Castle and the Dunbar ; the greenhulled clippers coming in – Thermopylae and Salamis and Aristides; and the little Blackadder and the Cutty Sark ; Joseph Conrad’s own Otago; the Liverpool ships of the gold rush days – Lightning and Red Jacket and Flying Cloud

Charmian Clift on the terrace of the Hydra house she shared with her husband, George Johnston, c 1956. Images courtesy Charmian Clift Estate. Reproduced with permission

There is a headland juts into the view from my window, a scrubby promontory scarred with grey and orange that tumbles down to weedy shoal. Perhaps one day I will be tempted to blink twice, and through Aegean rigging suddenly out-of-focus I might see – rounding the headland cautiously in a white whirl of gulls – some little bluff-bowed ship that will need no heraldry for identification. Sirius, say. Or the brig Supply. With the paintwork faded to nondescript – the sort of bleached and weathered look a working boat wears at the end of a long journey. A very long journey.

Text © Charmian Clift Estate. Reproduced with permission. Clift’s final, unfinished novel, The End of the Morning , has just been published by NewSouth Press: https://unsw.press/books/the-end-ofthe-morning/

01

Charmian Clift in her house in the Greek island of Hydra, 1957.

Oh! What a lovely war

Prisoners in Arcady

The internees used bush timbers and bark slabs to construct 49 riverside huts and clubhouses complete with jetties for their home-made boats

A boat decorated for the 1916 Venetian Carnival on the Wingecarribee River with the internees’ Heideheim Villa in the background.

All images Berrima District Historical & Family History Society

In the earliest days of World War I, crew members from the German cargo steamship Pfalz and the infamous raider Emden were interned in the small New South Wales town of Berrima. There they spent the remainder of the war in industrious peace, constructing a village, building and sailing a variety of eccentric craft and establishing a thriving and harmonious community, writes Bruce Stannard AM .

AUSTRALIA’S INVOLVEMENT in the First World War began on 4 August 1914. The declaration was made in London at 11 pm GMT, which in Melbourne was 9 am AEST on Wednesday 5 August. Earlier that morning, Captain Wilhelm Kuhleken, master of the 6,500-ton Norddeutscher Lloyd cargo steamship Pfalz, prepared to depart No 2 Victoria Dock under the guidance of the Port Phillip Pilot Service’s Captain Frederick Henry Robinson. With the official declaration of war expected at any moment, Captain Kuhleken was anxious to proceed to sea. Heavy traffic on the Yarra River delayed Pfalz getting clear of the river and she steamed slowly toward The Heads. Near Portsea, the Pfalz was released from naval inspection, and with no legal impediments to her departure, she was free to head out into Bass Strait. But at that moment, the Royal Australian Artillery Garrison at Fort Queenscliff, on the opposite side of The Heads, received news by telephone and heliograph that the federal Solicitor General, Sir Robert Garran, had at last signed the official legal instrument authorising military action. Then came the unequivocal order: ‘Stop her or sink her!’

The naval officers from the Emden built Emden Villa, their own clubhouse with its impressive veranda commanding splendid views over the river

01 German mariners interned at Berrima pose beside the rustic log cabin they built on a rocky outcrop overlooking the Wingecarribee River at Berrima.

02

Under painted paper lanterns and boughs of scented boronia, German merchant service officers sit down to Christmas dinner in the sandstone confines of the old Berrima Gaol.

As the Pfalz passed through The Rip, Captain Kuhleken ignored the flag signal to ‘heave-to’ and despite the pilot’s protests, he insisted on steaming toward The Heads and the open sea beyond. German consular officials came onto the bridge and cheered what looked certain to be their narrow escape. Their jubilation was short lived. On board the Naval Examination Service vessel SS Alvina, an alert young midshipman, Richard Veale, smartly hoisted the white and red International Signal Flag H –identifying the Pfalz as a hostile vessel. That signal was followed by an immediate response from Fort Nepean’s artillery crew. Bombardier John Purdue opened fire with a booming warning shot that saw a 100-pound shell from a 6-inch gun strike the water close to the steamship’s stern. A huge plume of white spray showered the bridge. The pilot immediately ordered ‘full astern’, but when Captain Kuhleken insisted on ‘full steam ahead’, the pilot, Captain Robinson, warned that the next shot would very likely be aimed directly at the ship.

It was only when a second warning shot was fired from Fort Nepean that Captain Kuhleken reluctantly ordered the Pfalz to stop. It was then 12.45 pm on Wednesday 5 August 1914. In London it was 2.45 am GMT the same day. Thus, Fort Nepean earned the dubious distinction of discharging the first shot fired by the British Empire in World War I. The Pfalz struck her black, white and red German tricolour in surrender and Captain Kuhleken and his crew were taken into custody as prisoners of war. The Pfalz was seized and forfeited as a war prize.

Throughout ‘the war to end all wars’ the federal government maintained prisoner-of-war detention camps at Holsworthy, Bourke, Molonglo in Canberra, at Trial Bay on the north coast of New South Wales and at Berrima in the NSW Southern Highlands. In these camps thousands of men designated as ‘enemy aliens’ were interned for the duration of hostilities. In the tiny village of Berrima, 329 German prisoners were housed within the formidable sandstone walls of the 19th-century gaol overlooking the pellucid waters of the Wingecarribee River. Among the Berrima internees were Captain Kuhleken and the officers and crew of the Pfalz. They were interned together with the surviving sailors and officers from the German commerce raider Emden, which was wrecked in the Cocos Keeling Islands on 9 November 1914 during her epic battle with the Australian light cruiser HMAS Sydney

Many of the internees wrote of their sadness at leaving ‘this wonderful place’ by the river where they had spent four years in peace and tranquillity

As capable seafarers, the German sailors naturally formed a cohesive and resourceful community. They were well educated, well disciplined and closely bonded by their proud maritime cultural heritage.

Mustered at Sydney’s Central Station, the internees were taken by steam train to Moss Vale in the Southern Highlands and marched along the nine kilometres of dusty country lanes to Berrima, the village founded in 1831 on the meandering Great South Road, then the main road linking Sydney and the inland city of Goulburn. The village was essentially unchanged since the colonial era in which the impressive gaol and the adjacent sandstone courthouse were built. Although the internees quickly dubbed the gaol ‘Castle Foreboding,’ the mariners were not unduly fazed at the prospect of living cheek-by-jowl in cramped, dimly lit and musty quarters. Each prisoner was issued with two woollen blankets and a straw-filled palliasse. Their two-metresquare cells were certainly spartan and freezing cold in the depths of the Highland winters, but the uncomplaining seamen soon installed their few personal possessions and made their cells habitable.

The Berrima camp was organised by a committee made up entirely of elected German officers and NCOs. The internees were each week well supplied with excellent quality beef, lamb and pork, freshly slaughtered locally.

The sailors soon refurbished the gaol’s cast-iron ovens, creating a wood-fired bakery turning out loaves of fresh bread and cakes. The authorities gave the internees permission to roam freely within a threekilometre radius of the gaol. A high fence was erected around the perimeter and within this sylvan setting, which included the broad Wingecarribee River and its rich alluvial flats, the men established their own flourishing vegetable gardens and orchards.

They used bush timbers and bark slabs to construct 49 riverside huts and clubhouses complete with jetties for their home-made boats. The ships’ officers built Erholung, an elaborate cottage for their exclusive use. The naval officers from the Emden built Emden Villa, their own clubhouse with its impressive veranda commanding splendid views over the river. There, in the privacy of a grassy, brush-walled solarium, the naturists among the Emden survivors indulged in naked sun-bathing. The heath-and-sapling huts along the river bank were given nostalgic German names: Schloss am Meer (Castle on the Sea), Heideheim Villa and Alsterburg. In this bucolic setting far from the sea there were no fewer than six high-ranking German captains, all of whom had no difficulty maintaining good order and discipline.

01

The paddle-wheeler Emil, propelled by a cranked axle turned by the coxswain’s feet.

02

In a masterpiece of German engineering, 12 internees form a carefully constructed ‘tower of strength’ on the banks of the Wingecarribee River, c 1916.

03

The bicycle boat, an ingenious pedal-powered paddle-wheel catamaran.

The mariners wasted little time in building a flotilla of watercraft, including impressive rowing skiffs, slender lightweight kayaks and a large gaffrigged dugout canoe

01 Captain Hannig’s hydroplane entry in the internees’ boating carnival on the Wingecarribee River, c 1918. The boat won first prize. It was his adaption of a bicycle boat built earlier, pictured on page 41.

02 Internees boating on the Wingecarribee River, c 1916. In the background are huts that they built, with washing on the line.

The beautiful Wingecarribee River became their Grosse See (Big Lake) – the centre of their existence. The mariners wasted little time in building a flotilla of watercraft, including impressive rowing skiffs, slender lightweight kayaks and a large gaff-rigged dugout canoe, big enough for five seated paddlers. They named the canoe Störtebeker after the notorious German pirate who plundered Hanseatic trading ships in the late 14th century. The mariners swam in the river and staged regattas and elaborate aquatic carnivals. On Kaiser Wilhelm II’s birthday (28 January), the river became the venue for a spectacular waterborne frolic with all manner of fanciful craft, including Hansa, a floating Zeppelin; a beautifully accurate two-man model of Hanover, the Kaiser’s luxurious steam yacht; a ‘submarine’ complete with a mock cannon mounted on the foredeck; a dragon boat; a Venetian-style gondola; and a bicycle-powered catamaran affectionately named Emil. There was also a superb two-man largescale model of the mighty five-masted, full-rigged ship Preussen, ‘the pride of Prussia.’ The first prize was awarded to a floating biplane emblazoned with the German military emblem, the Teutonic Schwarzes Kreuz (Black Cross).

Profits from the camp’s bakery were channelled into the purchase of musical instruments for a band. When the sailors weren’t messing about in boats, they were singing in their camp choir or involved in producing German comic theatre and gaiety musicals to which the Berrima people were always invited. After the Armistice was signed on 11 November 1918, an air of despondency descended and became more pronounced in the succeeding months as the onerous terms for war reparations were exacted by the victorious Allies.

It was not until 1919 that the German government chartered a ship to bring the internees home. A train took them direct to Darling Harbour, where the White Star liner SS Ypiranga waited to return them to their war-ravaged homeland. Many of the internees wrote of their sadness at leaving ‘this wonderful place’ by the river where they had spent four years in peace and tranquillity.

Today there is no trace of the old German encampment at Berrima. On the eve of their departure, the internees destroyed their huts and their boats. Only the hull of their cherished dugout canoe Störtebeker was left on the riverbank. Now, 110 years later, a forest of whitebarked gums has reclaimed the tranquil riverbanks. It was there that lines from Wordsworth’s famous sonnet came floating back to me: ‘As I cast my eyes I see what was, and is and will abide. Still glides the stream and shall forever glide.’

Bruce Stannard AM is a renowned maritime author and a Life Member of the Australian National Maritime Museum.

Hydrographic chart entitled Part of Hunter’s River (or the Coal River) surveyed by Lieutenant Charles Jeffries [sic] Commander of HMG Brig Kangaroo, 1816 The location of three shipwreck sites, including that of Estramina, appear on this chart. Image State Library of New South Wales

The remarkable tale of the Estramina

A South American vessel wrecked in Australian waters

On 19 January 1816, His Majesty’s Colonial Schooner (HMCS) Estramina wrecked on the notorious Oyster Bank at Newcastle, New South Wales, while attempting to depart the Hunter River. Its loss marked the end of a distinguished and eventful career that began in Spain’s South American colonies and included hydrographic surveys, piracy, convict transportation and a coup d’état. Dr James Hunter reveals the story of one of Australia’s few shipwrecks of legitimate Spanish origin.

ON THE EVENING OF 16 NOVEMBER 1800, the Spanish fifth-rate frigate Santa Leocadia approached Santa Elena, a small coastal community near the entrance to the Rio Guayas and port city of Guayaquil, an important mercantile and shipbuilding centre in the then-Viceroyalty of Peru. Under the command of Capitán de Navío (Captain) Antonio Barreda and armed with 34 guns, Santa Leocadia was a capital warship in Spain’s Armada del Mar del Sur (South Sea Navy) and at the vanguard of a convoy of naval and merchant vessels sailing to Panama. Within the frigate’s hold was the situado (military payroll) for the Spanish garrison at Panama City and several merchant consignments, totalling more than a million pesos in gold and silver specie. The ship also carried four passengers and 34 British prisoners.

Santa Leocadia sailed ahead of the convoy to reconnoitre Puntilla de Santa Elena, the westernmost point of continental South America, when it ran aground on an uncharted reef around 8.30 pm.

The ship quickly began to break up, resulting in the loss of 140 of its crew of 301. Forty-eight other crewmen were injured. Incredibly, no passengers or prisoners were injured or killed and all were safely transferred to Panama. Over the course of eight months, extensive salvage operations recovered more than three-quarters of the specie, as well as 28 of the ship’s 34 cannons. Salvage also targeted Santa Leocadia itself, including the removal of accessible ship’s timbers and other elements of its hull architecture.

Within a year, several of Santa Leocadia ’s salvaged timbers would find new life in the hulls of two naval schooners under construction at the Guayaquil shipyard of León Aycardo. Both were specially built to conduct hydrographic survey work along the Pacific Coast of Spain’s South American colonies. Their names were San Juan de Mata (more commonly referred to as Alavesa) and Extremeña

Extremeña was the first to slide down the ways, on 13 October 1802, and sailed to Callao the following month, where it was commissioned a Goleta de Guerra (armed schooner) under the command of Teniente de Navío (Lieutenant) Mariano de Isasbiribil y Azcárate. The 102-ton vessel measured 70 feet (21.3 metres) overall. Six hundred quintals (approximately 28 tonnes) of ballast were placed in the schooner’s hold to stabilise the hull. Although pierced for 12 cannons, Extremeña was only armed with four 4-pounders when commissioned, and during its subsequent hydrographic voyages in Spanish naval service.

The schooner embarked on its first hydrographic survey voyage in April 1803, sailing to Valparaíso as an auxiliary to the Spanish naval brig Peruano. The two vessels’ crews drafted a chart of Valparaíso’s port, then proceeded north along the Chilean coast and undertook surveys of the ports of Quintero, Papudo and Pichidangui during October 1803. A second hydrographic voyage the following month travelled south, visiting the Chilean ports of Chiloé, Valdivia, Talcahuano and Santa María Island, before returning to Valparaíso in March 1804.

On 20 June 1804, Extremeña and Peruano again sailed north to survey the port of Coquimbo. Seven days later, Peruano was damaged during a storm and forced to return to Valparaíso. Isasbiribil was ordered to continue to Coquimbo and survey adjacent bays and harbours between Lengua de Vaca and Punta de Teatinos. In late July, Extremeña returned to Coquimbo with orders to remove four foreign sealing vessels suspected of illegal fishing and smuggling. With the port cleared of interlopers, the schooner journeyed north and conducted a series of coastal surveys before arriving in the port of Huasco. It then continued to Copiapó (modern-day Caldera, Chile), arriving on 16 September 1804.

Although pierced for 12 cannons, Extremeña was only armed with four 4-pounders when commissioned

On 29 September, Isasbiribil received intelligence that a heavily armed British privateer had attacked Coquimbo five days earlier and taken possession of the Spanish merchant brig San Francisco y San Paulo Extremeña ’s four cannons were brought out of the hold and mounted on carriages, and preparations made to leave Copiapó and search for the British vessel. However, contrary winds prevented the schooner’s departure, and Isasbiribil was still awaiting favourable conditions when an unidentified brig arrived at the mouth of the port the following morning.

The unfamiliar vessel was Harrington, a 180-ton snow operating under a Letter of Marque from the Presidency of Fort Saint George (an administrative subdivision of British India) and armed with six 12-pounder carronades, as well as six 6-pounder and two 3-pounder long guns. Harrington ’s captain, William Douglas Campbell, was a Sydney-based merchant who had conducted illegal trade along the Chilean coast in 1802 and 1803 on behalf of a Bengali trading house. He was returning to do more of the same in September 1804 when he heard in Tahiti that war had erupted between Spain and Great Britain. This information proved false, but Campbell saw it as an opportunity to harass Spanish shipping and take prizes. While at Más Afuera (modern-day Alexander Selkirk Island), Campbell discovered Peruano and Extremeña were operating off the Chilean coast and decided to seek out and engage them. Harrington attacked and seized San Francisco y San Paulo shortly thereafter.

Draught of an armed schooner of the Spanish Navy, c 1800. Extremeña would have been built according to similar lines and resembled this vessel.

Image Archivo Histórico de la Armada JS de Elcano, Madrid

Extremeña embarked on its first hydrographic survey voyage in April 1803, sailing to Valparaíso as an auxiliary to the Spanish naval brig Peruano

Extremeña returned to Coquimbo with orders to remove four foreign sealing vessels suspected of illegal fishing and smuggling

Hydrographic chart titled Plano del Puerto de Pichidangui, Levantado por los Oficiales del Bergantin Peruano, y Goleta Extremeña, Ano de 1803 (Plan of the Port of Pichidangui, Surveyed by the Officers of the Brig Peruvian, and Schooner Extremeña, in the year 1803). This chart was one of several generated from Extremeña ’s survey work along the South American coast before it was seized by the Harrington. Image Spanish Ministry of Culture, Biblioteca Virtual del Patrimonio Bibliografico

Isasbiribil quickly realised his vessel was disadvantaged, not only in terms of firepower, but also its ammunition stock, which only comprised 21 round shot. Nevertheless, he ordered Extremeña prepared for action and anchored close to shore to ensure a successful retreat should the battle be lost. Extremeña fired the first shot at 9 am, which was immediately answered by a volley from Harrington. Isasbiribil and his crew acquitted themselves well and kept up steady fire for about an hour, but ultimately ran out of ammunition. At this point, Campbell ordered a boarding party to take Extremeña and cut off the crew’s escape. The Spanish captain had prepared for this possibility and commanded his vessel be beached and set on fire to prevent capture. Most of the schooner’s crew were then evacuated ashore with Isasbiribil’s commission and other sensitive documents, while he and a small group of officers spread sulphur throughout the cabin and set it alight.

The fire proved ineffective, and the boarding party was able to put it out. A prize crew took charge of Extremeña, and it departed Copiapó with Harrington and San Francisco y San Paulo. The three vessels set a course for Tahiti and then split up, with Harrington reaching the islands in November 1804, and the Spanish vessels arriving the following month. Extremeña then sailed to Jervis Bay, about 150 kilometres south of Sydney, where the prize crew hid it from sight and awaited further instructions from Campbell. Instead, they were discovered by the crew of His Majesty’s Armed Tender Lady Nelson on 5 April 1805 and apprehended while attempting to leave the bay.

The schooner was brought into government service and rechristened with the Anglicised name Estramina

01

02

of Lt

of the

The last recorded mention of this remarkable vessel occurred on 3 May 1817, and in subsequent years, Estramina disappeared beneath the waves

News of Campbell’s activities on the Chilean coast reached New South Wales Governor Philip Gidley King shortly before Harrington ’s return to Port Jackson in March 1805, and he determined that Spain and Great Britain were not at war at the time Extremeña and San Francisco y San Paulo were seized. This meant their capture was illegal and King responded by detaining Harrington, Campbell and the crew. Extremeña, flying the Spanish ensign and escorted by Lady Nelson, arrived at Port Jackson on 9 April, after which King ordered it surveyed and fitted out as a supply vessel for Norfolk Island and settlements in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania). The schooner had completed several voyages on the colonial government’s behalf by April 1806, when official news of war between Spain and Great Britain reached Sydney, and it was claimed as a prize by the British government. However, the Vice Admiralty Court ruled Extremeña was not a legal prize and should be put up for auction, with the proceeds placed in trust. King found the vessel so useful he ordered the colonial government to lodge a bid of £2,100, which was successful. The schooner was brought into government service and rechristened with the Anglicised name Estramina after undergoing repair and refit, including the addition of new copper sheathing.

Two years later, the schooner was involved in two significant events. The first was the Rum Rebellion against Governor William Bligh, which commenced on 26 January 1808. On the following afternoon, one of the leaders of the coup d’etat, Major George Johnston, ordered Estramina ’s commander, John Apsey, to lower Bligh’s Broad Pennant. This action visually symbolised the end of Bligh’s authority in the colony – an insult exacerbated by the coup leaders’ suggestion he immediately embark aboard the schooner and leave New South Wales. Bligh refused, owing to its small size and reportedly poor condition.