e annieryan@gmail.com

w annieryan.org

t 650-804-0944

e annieryan@gmail.com

w annieryan.org

t 650-804-0944

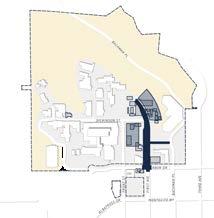

Campus Master Planning / Page / Project Manager / 2017 - 2019

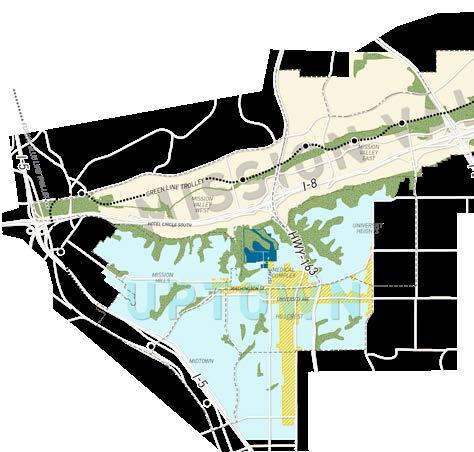

The Long Range Development Plan (LRDP) update for UC San Diego’s academic medical campus provides a redevelopment framework for the entire campus through 2030 and integrates new revenue generating mixed-use residential development and multi-modal circulation improvements with state of the art health care and medical research facilities.

As the only academic medical center (AMC) in the San Diego region, UC San Diego Hillcrest serves not only UCSD students and faculty, but also a wide range of patients from the greater San Diego region. Located in the Hillcrest neighborhood in the heart of San Diego, the campus is a unique and vital urban health center where research, patient care, and education converge, and where all of its stakeholders—physicians, students, and patients alike—expect comprehensive and innovative care and research.

In order for the campus to serve as a cornerstone of UC San Diego Health’s innovative and world-class health mission, this LRDP proposes new physical planning principles that will align future campus development with both UC San Diego, University of California, and City of San Diego smart growth and sustainability targets. With a context-driven approach, this LRDP identifies new strategies for physically and socially integrating a complete hospital redevelopment with its neighborhood surroundings, and provides a new model for academic medical centers that puts people and communities first.

The Hillcrest campus is located roughly 13 miles south of UC San Diego’s main campus in La Jolla, which hosts the bulk of UC San Diego Health academic and healthcare programs.

The distance between the two campuses creates significant challenges for faculty, staff, and students, and highlights the need for a robust inter-campus transportation strategy.

UC San Diego Hillcrest sits at the intersection of several diverse and rapidly evolving neighborhoods and community planning areas, with underlying urban design and regulatory conditions that create a unique future development framework for this central San Diego region.

Together, these conditions help define the kind of integrated urban community health facility that UC San Diego Hillcrest could become.

Site and timing for the replacement hospital facility have been the driving factors in this phasing strategy. The replacement hospital requires a significant footprint with access for both the public, service, and emergency vehicles, a new OSHPD Central Utility Plant, and direct access to parking. The seven-phase development strategy shown here illustrates how critical facility, transportation, and infrastructure improvements could be incorporated over a 15-year period without disrupting patient access to high-quality healthcare.

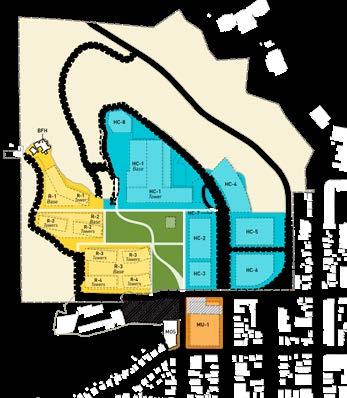

This LRDP proposes a 45% increase in total healthcare program and the addition of up to 1,000 residential units on campus. These projections are based largely on the fact that new healthcare development will be located within more intentionally designed buildings with new development codes and building technology that allow for more efficient building layouts.

Providing new housing and community-oriented uses on campus can help integrate the campus with the urban fabric of its surroundings, reduce vehicle dependency, for trips to and from campus, and help to ensure long-term financial success for the campus’s health-care services.

The future campus should include new active groundfloor and community-oriented uses that both provide daily amenities for the many people who work and live on the campus, as well as those who live and work in the surrounding neighborhood.

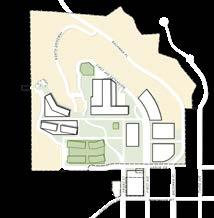

The new campus will feature a range of open space types, with varying levels of intended programming and public access. New open space types include public open spaces for recreation and community events, more contained spaces for quiet mediation, and preserved habitat areas that are not intended for human use.

A strategic sequence of demolitions and construction will begin with improvements to the campus arrival experience along First Avenue, and culminate with the construction of the final phase of multi-family residential units. In between, a new hospital building will be constructed, along with a new outpatient facility, a multipuposed facility, a community wellness center, and more multi-family housing.

Campus Master Planning / Page / Project Manager / 2018 - 2019

In crafting its marine science research campus master plan, San Francisco State University envisions a dynamic and transformative new campus experience where science, art, humanities, and the bay environment all converge. Recognized as one of the most ethnically diverse public universities in the county, and boasting a legacy of social justice and activism, San Francisco State has a unique opportunity to train a more diverse generation of marine scientists and bring new voices to the climate change conversation.

Further, given the campus’s proximity to the Bay, future site and programmatic design will offer new opportunities to study and witness the impacts of sea level rise, an introduce a more resilient shoreline.

Today, the campus hosts a combination of research, academic, and community programming. Most of these activities are operated directly by San Francisco State University’s Esutary and Ocean Science Center, an interdisciplinary program for scientific study of the sea and coastal communities.

SF State faculty and students split their research activities and courses between both Romberg Tiburon and the City Campus in San Francisco. Most faculty and students affiliated with Romberg Tiburon and the EOS Center are based within the College of Science and Engineering, although numerous other SF State colleges have relationships with the campus. This existing multidisciplinary spirit highlights the broad reach of climate change and the further need for creative, interdisciplinary strategies for addressing its impacts in the future.

The campus also hots several partner organizations, with the primary being the SF Bay National Esturarine Research Reserve (NERR) and the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC).

Today, the campus is largely comprised of centuryold buildings dating back to the site’s occupation by the US Navy. Many of the buildings are either grossly underutilized or entirely vacant due to decades of deferred maintenance.

Access to the campus is a challenge for all campus users, regardless of their point of origin. Located in a realtively remote part of southern Marin County on the Tiburon Peninsula, there is no direct transit access to the campus, nor are there pedestrian or bicycle facilities along Paradise Drive, the single point of access to the campus.

Driving can take over an hour and requires reliable access to a vehicle. With public transit, travel time from the City Campus takes at least 75 minutes across three different travel modes.

And yet, RTC’s location along the Bay offers unique potential for exploring more innovative transportation modes, particularly water access.

The existing campus topography, building conditions and uses, stormwater drainage patterns, and circulation system converge to create five key subareas for organizing the campus. Detailed existing conditions mapping offers helpful insights into how the campus is utilized today, how existing and changing natural systems like water flow and sea level rise impact the site, and how future campus design could leverage these conditions to create a more resilient and thoughtful development pattern.

An existing space analysis of the campus helps to reveal patterns of existing uses, and where larger pockets of vacant or underutilized space exists. The bulk of the campus’s active lab and resrearch space is located within the Science Core, while the Historic Cluster features the greatest proportion of vacant or red-tagged buildings out of all the subareas.

Small pockets of lab/research space scattered between upper and middle campus

Steep slopes, uneven surfaces, and few ADA elements combine to create an exceptionally difficult pedestrian environment on campus, despite its relatively walkable scale. Pedestrian access on campus is further convoluted by a lack of clear nodes or gathering spaces where several building entrances converge.

Steepest and narrowest routes, shared by cars

Master in City Planning Thesis / Dept. of Urban Studies and Planning, MIT / San Francisco, CA / 2017

Given the rapid rate at which income inequality and low-income displacement is transforming the power dynamics in many San Francisco neighborhoods, the Tenderloin serves as a vital laboratory for observing and questioning how it has resisted similar types of transformations over the last 50 years.

I employed a mixed methods research approach to catalogue the unique urban and social conditions of the neighborhood and review the impacts of critical historical events and top-down planning interventions in the neighborhood.

Relying heavily on data recorded over the course of a two-week field study, in addition to spatial analysis and stakeholder interviews, I found that the Tenderloin exhibits a profound agglomeration of poverty that has only grown more pronounced over the last five years since the start of a Mid-Market area tax break for tech companies. There is also an abundance of public life playing out in the neighborhood’s streets and sidewalks, but the public realm itself is highly restricted

From these findings, I developed three potential urban design strategies in which future public realm and tactical urbanism projects could be applied to the Tenderloin incrementally

Streets serve as open space for neighborhood residents. Boeddeker Park is popular with children, but overall most socializing and recreation is happening on the streets.

Not all corners are the same. Within 1 block, corner characteristics shift from hang-out spots for residents to more drug-oriented activity.

Street dwelling concentrates around large NPOs. Street dwelling does not occur randomly, and most larger clusters align with locations of major NPOs providing critical services.

STATIONARY ACTIVITY OBSERVATIONS AND PUBLIC REALM MAPPING

Stationary activities observed over two week period in spring 2017, between 9 AM and 7 PM, categorized by observed user type.

EXISTING TENDERLOIN DEMOGRAPHICS AND TAX BREAK FINDINGS

$25,895

Estimated Median Household Income (2015 ACS)

Tenderloin

Tax Break Area

San Francisco

45% of residents were born outside United States (2015 ACS) 52% of residents speak languages other than English (2015 ACS)

$33.7 million Money saved by Tax Break companies (2011 - 2014) ~$8 million Tax Break company donations to local NPOs (2011 - 2016)

RHYTHM OF PARCELIZATION WITHIN BLOCKS

The neighborhood’s present-day block structure shows clear signs of its original 1851 block network and parcelization, despite decades of redevelopment in the neighborhood. The persistence of the original parcelization highlights the irreversible implications of this rigid design, and the burden it places on new development to follow a predetermined design order. Change must always occur within an increment or multiple of the original lot proportions.

TYPOLOGIES OF AFFORDABLE HOUSING

The 15,770 total housing units present in the Tenderloin, all fall within one of three categories: market rate units, rent “stabilized” units, and affordable units.

Over half of the housing stock in the Tenderloin is considered ‘rent stabilized’, due to the effect of either a city-wide rent control protection or an SRO conversion ordinance on the property.

2011 TO 2017 CUMULATIVE EVICTION NOTICES EXISTING KEY JURISDICTIONAL BOUNDARIES

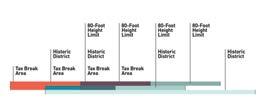

The Tenderloin sits within the boundaries of three distinct development restriction and economic incentive boundaries that have impacted the rate of physical and social change within the neighborhood for over four decades

Recent increases in the rate of eviction notices issued in the Tenderloin since the Tax Break began in 2011 indicate that these overlay tools have a profound impact on the Tenderloin. Further, when looking solely at the Tax Break Area, the total number of buildings effected by eviction notices drops while the density of notices within single buildings increases, suggesting a recurring pattern of eviction at key sites.

PARCELS CONTROLLED BY NON-PROFIT ORGANIZATIONS

Over 25% of the Tenderloin’s total parcel area is controlled by NPOs. Unlike Mid-Market tech companies which can uproot at anytime, these NPOs have multi-decade-dependent relationships with the neighborhood, and many occupy multiple properties within the Tenderloin.

PROPOSED HOUSING PROJECTS BY TOTAL UNITS

Total Units

Proposed

In San Francisco, market-rate developers must provide either on-site affordable units or fees to help finance the development of units elsewhere in the city. As it exists today, this policy presents a flawed scenario for the Tenderloin where market-rate development along its borders is both helping to ensure new affordable development within the neighborhood, and also helping to drive up land values and consequently encouraging land owners to seek a range of loopholes for evicting low-income tenants to take advantage of the land value.

Nearly one-half of all properties in the Tenderloin are controlled by long-term tenants or occupied by full-block developments

But public streets make up 30% of the neighborhood’s total land area, and together form a network of new potential open spaces.

STRATEGY 1

Nearly all Tenderloin SROs exist in a sort of development purgatory, where the cost of the renovations the existing building demands outweigh the revenue its rental income could generate. This scenario presents an opportunity for a new kind of SRO zoning overlay that would aim to accomplish what the original SRO Conversion Ordinance did not: preserve the SRO as a quality affordable housing model.

STRATEGY 2

At its core, tactical urbanism is about standing up to conventional planning practices that do not favor the user and offering tangible solutions that can evolve and grow over time. It is also about equity and recognizing when existing planning strategies create imbalances within a city.

Traditionally, tactical urbanism is introduced in places with an abundance of space but a lack of programming to guide people through it. By comparison in the Tenderloin, there is a critical need for space that can appropriately organize the public life and social programming that already abounds.

Off-street, private properties could provide more targeted, resource intensive activations that address the needs of existing residents’ regardless of housing status. Further, they could offer space for Tenderloin-based organizations to develop their own solutions for addressing neighborhood needs through lower risk, lower investment strategies.

New and proposed housing development in the Tenderloin largely leaves existing SROs untouched.

Shipping containers as pop-up storage or medical kiosk

serving free grab-and-go meals

Safe offstreet area for more sheltered and private resting

But if developers were encouraged to finance SRO renovation projects, rather than exclusively financing new construction...

...the overall density and quality of the neighborhood’s affordable housing stock would increase...

...without requiring the procurement of new land.

Neighborhoods like the Tenderloin present crucial opportunities to develop new street design practices that go beyond mobility and embrace the role of sidewalks and streets as dedicated forms of open space. The result could be a new type of complete street, where ‘complete’ refers not only to the types of mobilities served, but the types of social services and public amenities provided for stationary activity as well.

New designs for the Tenderloin’s sidewalks and streets could take on a pluralism approach with streetscape standards that offer targeted approaches for different block segments depending on whether longterm land uses or building owners are present.

By locating certain types of interventions where ownership change is less likely to occur, these tactical urbanism installations could become context-driven, public realm extensions of social service organizations and SROs.

By combining physical and programmatic building factors with the long-term land holder status of a parcel, the Tenderloin’s public realm could become an intentional and flexible network of open spaces that respond to the parcels they abut.

Station Area Plan / PlaceWorks / City of Mountain View, CA / 2013-14

The San Antonio Precise Plan is a blueprint for transforming development in the Plan Area from existing regional commercial into an accessible mixed-use core in proximity of multiple transit services and one of the Peninsula’s most heavily traveled corridors. The diagram to the right illustrates how San Antonio fits neatly into an existing chain of pedestrianoriented commercial corridors along the Peninsula that branch off of the Caltrain rail line and feature active pedestrian street life from morning to evening throughout the week.

A large portion of the Plan Area is within San Antonio Center, a 60-acre regional retail development sitting within an uninterrupted “super block” of parking lots, driveways, and large footprint retail buildings. As a place of limited human scale, the Plan presents a unique opportunity for more focused density within walking distance of train and bus stations. This plan is intended to serve as an accessible and highly graphic guide that will help public officials, residents, developers, and local advocacy groups understand the area’s underlying conditions and its potential for new integrated mixed-use development.

Station Area Plan / PlaceWorks / City of Walnut Creek. CA / 2012-14

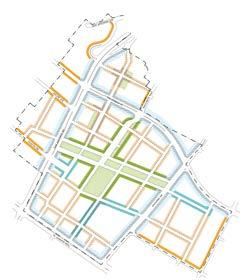

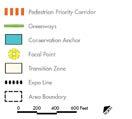

The West Downtown Specific Plan aims to provide a new kind of urban environment in Walnut Creek that encourages walking and bicycling for local trips, and accommodates higher intensity mixed-use development all in walking distance of the Walnut Creek Bay Area Rapid Transit station.

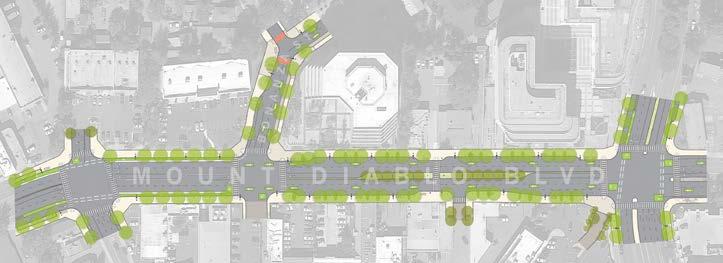

Improved streetscape facilities that complement adjacent mixed-use and higher density development are a key component of this transit-oriented Plan. The conceptual streetscape concepts (far right) illustrate the pedestrian and bicycle facility improvements that would transform Mount Diablo Boulevard from a high-speed, vehicle-oriented expressway into a more accessible, enjoyable, and human-oriented experience. The streetscape concepts are intended to serve as the templates for future public improvements that will occur alongside new private development within the Plan Area over the next 10 to 15 years. They incorporate bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure best practices tailored to the unique conditions of Mount Diablo Boulevard as a major regional corridor for the area.

Introducing bicycle facilities within an existing rightof-way becomes a study in “give and take”. Residents in Walnut Creek expressed strong desire for new bicycle facilities along Mount Diablo Boulevard, but not at the expense of the pedestrian. The proposed multi-modal streetscape design addresses these concerns by imagining the street as two distinct zones: one which prioritizes bicycle traffic and facilitates protected bicycle travel between the BART station and existing bicycle routes in the city; and another zone which caters to the pedestrian experience and extends the streetscape experience of Downtown Walnut Creek further to the west.

Open space locations are strictly conceptual. With the exception of the green space shown at the intersection of Oakland Blvd. and Trinity Ave., the location of open spaces will likely be determined with the coordination of specific development projects.

Proposed new streets are strictly conceptual. They would occur upon private redevelopment and may not occur in the exact locations shown on this map.

Existing land uses adjacent to the Plan Area Boundary are shown for reference and are not part of the Plan.

Station Area Plan / PlaceWorks / City of Santa Monica, CA / 2011-13

With the opening of the Expo Light Rail connecting Downtown Los Angeles to Santa Monica, the Bergamot Plan Area—already a cutting-edge, unique collection of places and activities—is poised for an additional flurry of new activity and development. The purpose of the Plan is to lay out a vision for how the Bergamot Area will be transformed in a way that benefits the community, and to provide a road map for how that vision can be achieved.

The Plan examines new transit-oriented development opportunities for an area renowned for its eclectic mix of creative arts and manufacturing industries, and includes innovative form-based development and streetscape standards that will provide realistic guidelines for developers while still addressing the community’s concerns related to development intensity and design quality.

Santa Monica has a long tradition of envisioning its streets as extensions of the public realm and as viable sources of open space and recreation. Frontage and streetscape standards for the Bergamot Area Plan will ensure that new development and open spaces work in harmony with the existing street network and also reflect the unique character and scale of the varied street types found in the Plan Area.

B.4.01 Ratio for Large Projects. For parcels of over 120,000 square feet in area in the Mixed-Use Creative District, projects shall provide a mix of commercial and residential uses as shown in Table 5.03. The ratio is expressed in floor area and can vary from the ratio up to 10% in either direction for flexibility. The mix of uses can be achieved as vertical mixed-use (on top of each other) or horizontal mixed-use (in neighboring buildings) (see Figure 5.05 for illustration).

B.4.01 Ratio for Large Projects. For parcels of over 120,000 square feet in area in the Mixed-Use Creative District, projects shall provide a mix of commercial and residential uses as shown in Table 5.03. The ratio is expressed in floor area and can vary from the ratio up to 10% in either direction for flexibility. The mix of uses can be achieved as vertical mixed-use (on top of each other) or horizontal mixed-use (in neighboring buildings) (see Figure 5.05 for illustration).

B.4 Mix of Uses

B.4.01 Ratio for Large Projects For parcels of over 120,000 square feet in area in the Mixed-Use Creative District, projects shall provide a mix of commercial and residential uses as shown in Table 5.03. The ratio is expressed in floor area and can vary from the ratio up to 10% in either direction for flexibility. The mix of uses can be achieved as vertical mixed-use (on top of each other) or horizontal mixed-use (in neighboring buildings) (see Figure 5.05 for illustration).

B.4.02 Ground Floor Commercial. Residential projects shall have a commercial component on the ground floor along street types that require active ground floors (see B.10 StreetBased Frontage Standards).

B.4.02 Ground Floor Commercial. Residential projects shall have a commercial component on the ground floor along street types that require active ground floors (see B.10 StreetBased Frontage Standards).

B.4.02 Ground Floor Commercial. Residential projects shall have a commercial component on the ground floor along street types that require active ground floors (see B.10

Based Frontage Standards).

B.5 Building Modulation of Top Floors

B.5 Building Modulation of Top Floors The top two floors of new Tier II or Tier III buildings shall adhere to set standards for maximum footprint. They are limited to a percentage of the largest floor plate in the building, which may or may not be the ground floor. One- and two-story buildings are exempt from these standards (see Table 5.03 and refer to Figure 5.06 for illustration).

The top two floors of new Tier II or Tier III buildings shall adhere to set standards for maximum footprint. They are limited to a percentage of the largest floor plate in the building, which may or may not be the ground floor. One- and two-story buildings are exempt from these standards (see Table 5.03 and refer to Figure 5.06 for illustration).

The top two floors of new Tier II or Tier III buildings shall adhere to set standards for maximum footprint. They are limited to a percentage of the largest floor plate in the building, which may or may not be the ground floor. One- and two-story buildings are exempt from these standards (see Table 5.03 and refer to Figure 5.06 for illustration).

B.6 Maximum Building Floor Plate

B.6.01 In order to create an attractive and pleasant environment that is respectful of human scale, floor plates of new buildings are limited to the maximum square footage set in Table 5.03.

Maximum Building Floor Plate

B.6.01 In order to create an attractive and pleasant environment that is respectful of human scale, floor plates of new buildings are limited to the maximum square footage set in Table 5.03.

B.6.01 In order to create an attractive and pleasant environment that is respectful of human scale, floor plates of new buildings are limited to the maximum square footage set in Table 5.03.