Leveraging Boston's Building Boom to Advance Equity

Andrea Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea P. Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea P. Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea P. Leers with Anthony Averbeck

Andrea P. Leers with Anthony Averbeck

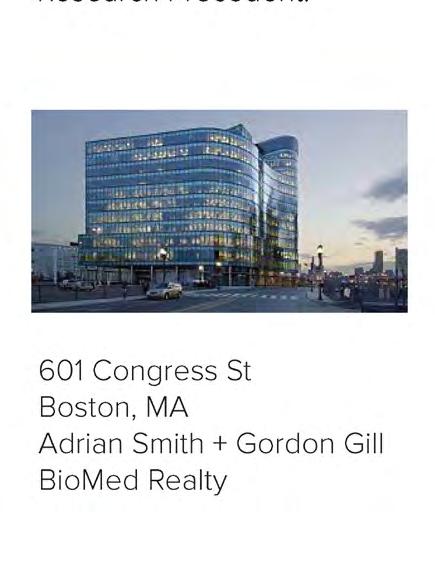

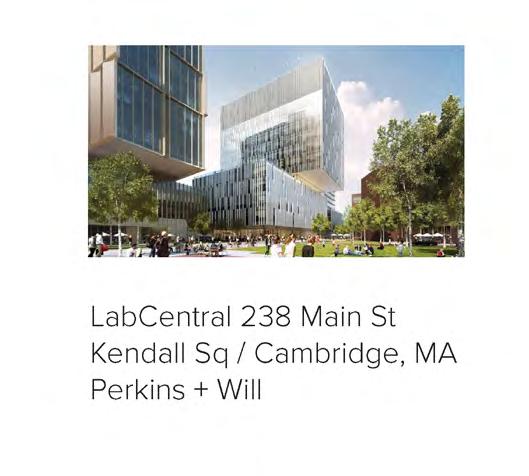

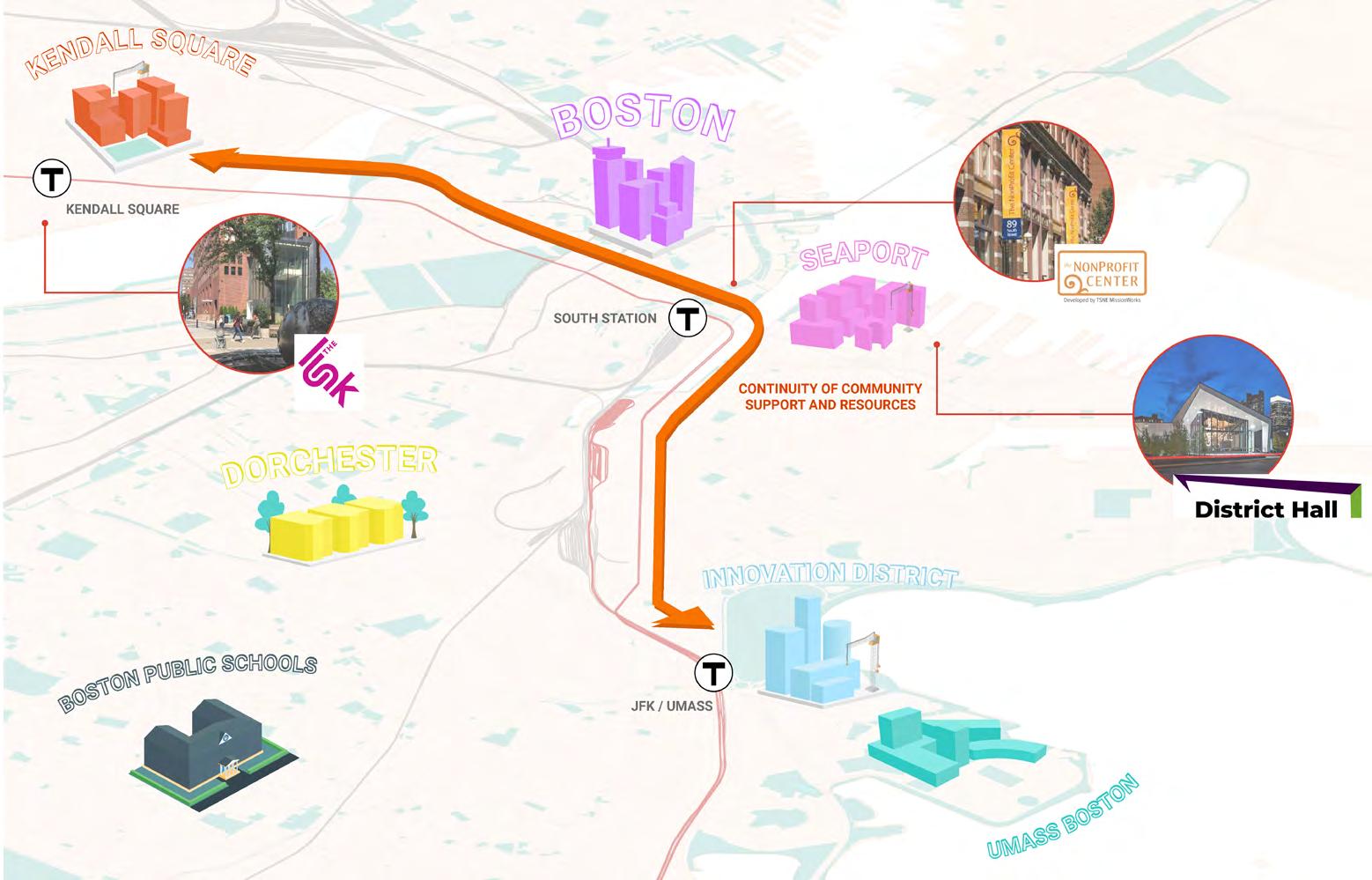

For the past ten years, the Boston metropolitan area has seen explosive growth due to its global attraction as a center for technology innovation. Development for “meds and eds” (major hospitals and research institutions) is fueling enterprise districts such as Kendall Square, the Seaport, and the planned Allston Enterprise campus. The challenges each district face center on keeping them attractive and welcoming for all, providing access for jobs and housing to surrounding communities, and maintaining the quality of urban design for which Boston is justifiably admired.

Report Editors

Andrea P. Leers

Anthony Averbeck

Pinyang Chen

Instructor

Andrea P. Leers

Teaching Associate

Anthony Averbeck

Students

Saad Boujane

Pinyang Chen

Danny Kolosta

Adriana Lasso-Harrier

Dianne Lê

Zhuoer Mu

Naksha Satish

Midreview Critics

Yun Fu

Gary Hilderbrand

Alex Krieger

Final Review Critics

Shannon Bassett

Shauna Gillies-Smith

Alex Krieger

Rahul Mehrotra

Peter G. Rowe

Claire Weisz

Sarah M. Whiting

Studio

Andrea

P. Leers Anthony AverbeckWe would like to thank all of those who helped in the preparation, support, research, and advancement for the studio and its related activities. We appreciate the learning opportunities these engagements provided us, and we offer this document as a stimulus to future reflections on the site and on the program of enterprise and innovation districts.

Frank Baker Boston

City Councilor, District3

for sharing his vision for the development and the interests of his constituents in Dorchester.

Matthew Fenlon

Assistant Chancellor, University of Massachusetts - Boston

for his valuable orientation to the present site conditions and the interests of UMass, along with his warm welcome during our site visit.

Sarah M. Whiting Dean, Harvard Graduate School of Design

Rahul Mehrotra Chair of Department of Urban Planning and Design, Harvard Graduate School of Design

for their support and guidance for the work of this studio and its research.

Alex Krieger

Professor in Practice of Urban Design, Emeritus, Harvard Graduate School of Design

Emily Mueller De Celis Partner, MVVA

for enlarging the perspective of the studio through lectures and contributions to the integrated ressearch investigations.

As one of the elected officials representing this area, I know that the Dorchester Bay site can bring unprecedented innovation and investment to this neighborhood of Boston, and I looking forward to seeing it come to fruition. I have appreciated the opportunity to comment on the Dorchester Bay City (DBC) proposal for the Columbia Point peninsula. The current development proposal (DBC) is planning to provide approximately 5.9 million square feet of new, mixed-use development on this site. The asphalt parking lot that currently exists would be transformed to a multi-use community, resulting in multiple pathways to economic opportunities for residents.

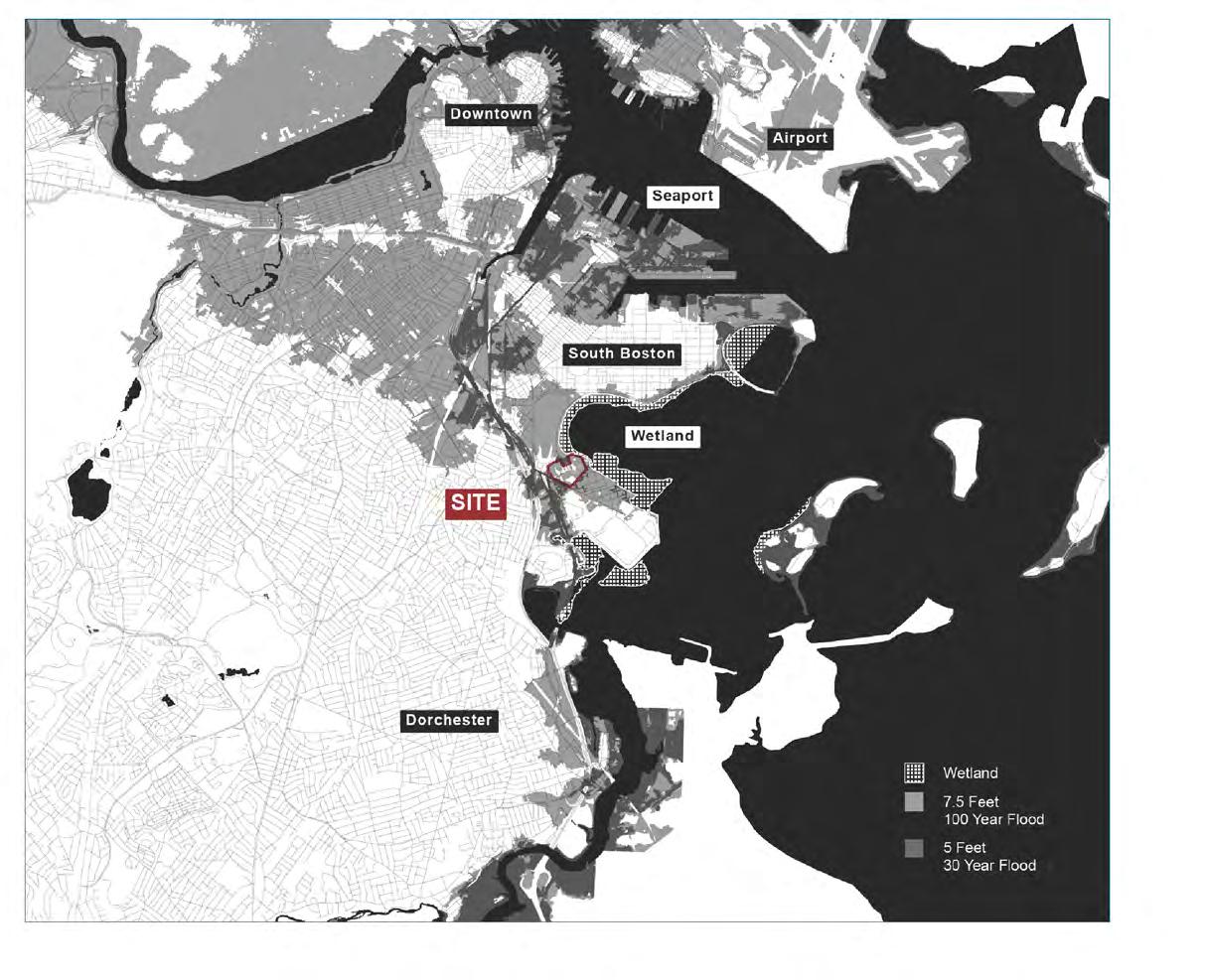

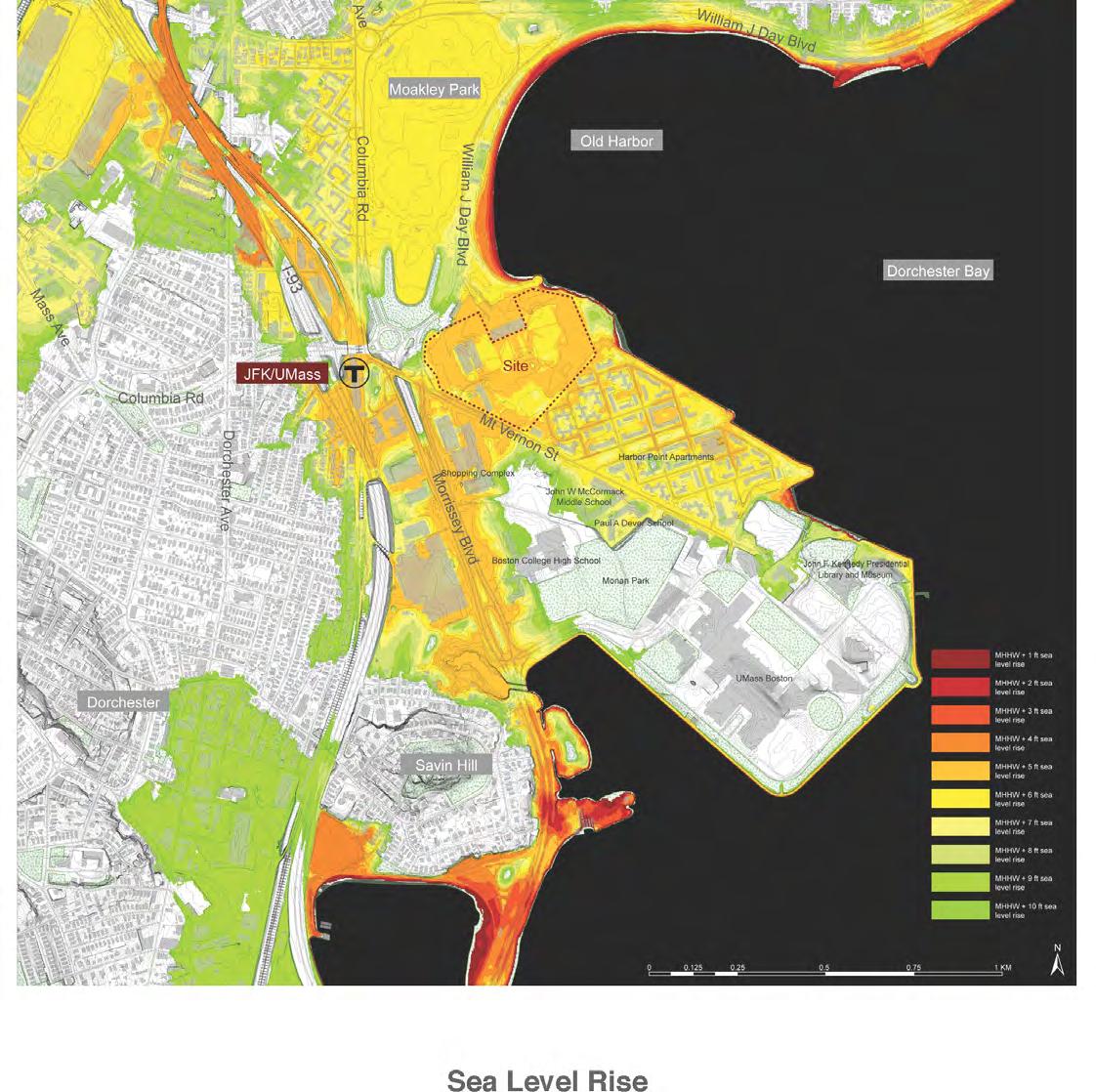

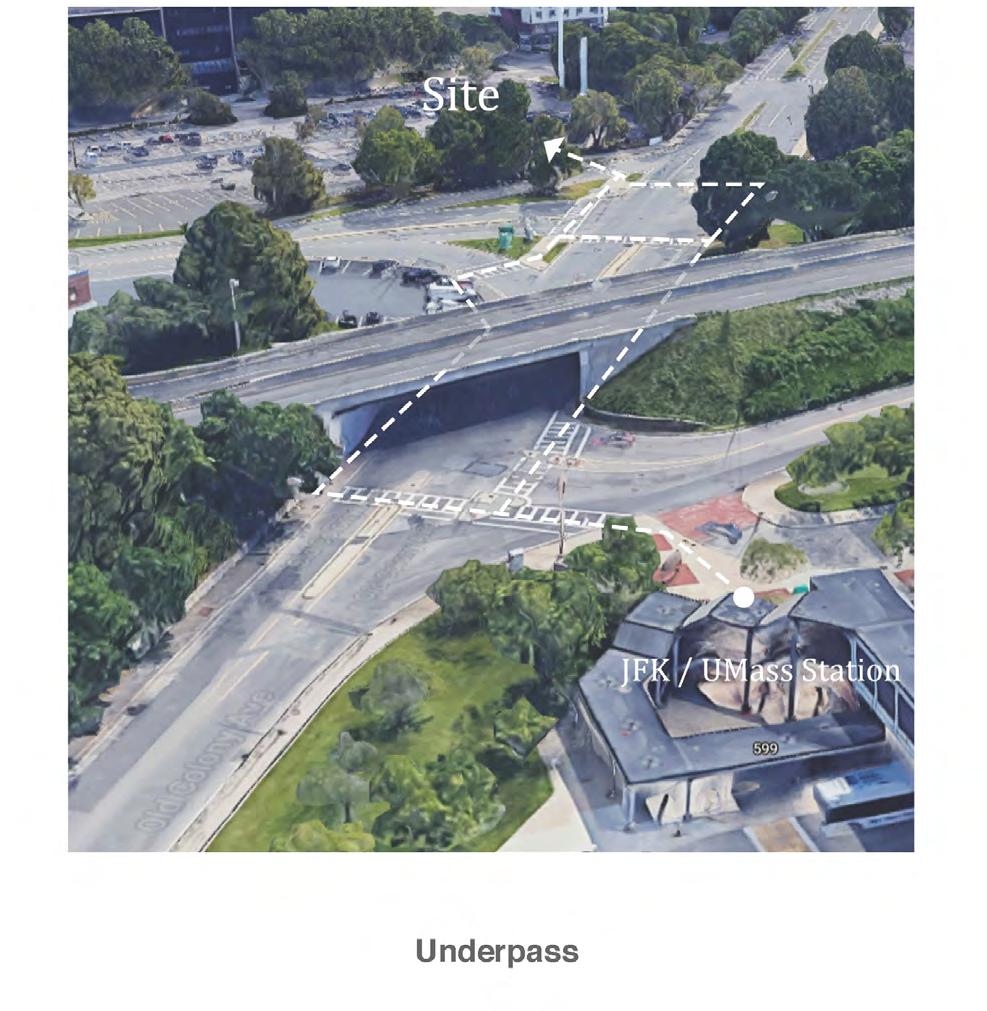

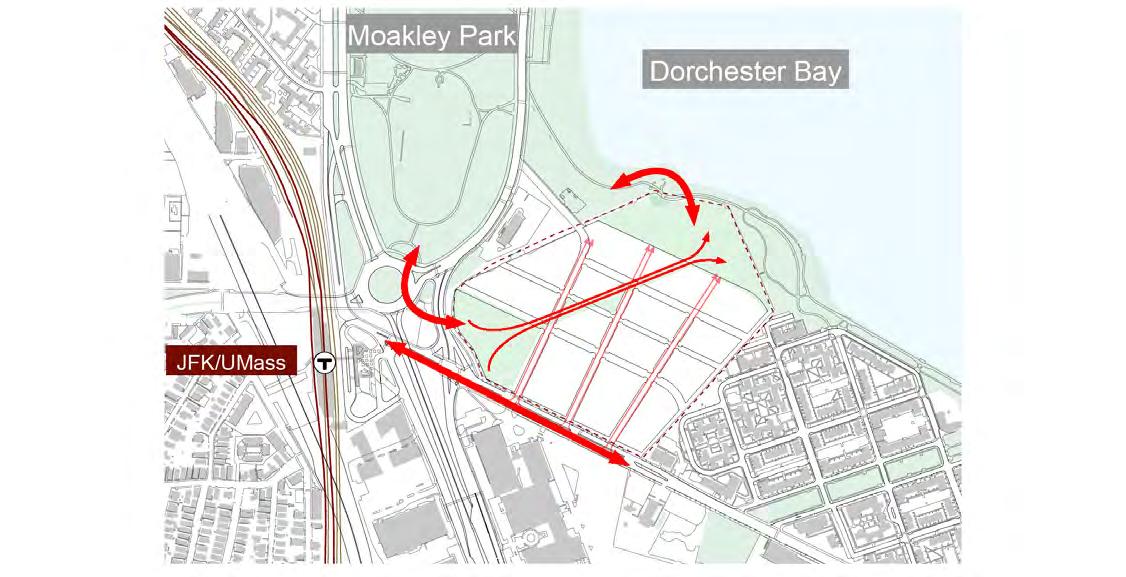

Equally important, DBC has the potential to unlock much-needed transportation, pedestrian, and infrastructure improvements, such as: permanent solutions to Kosciuszko Circle; improvements at the JFK/UMASS train station; and investments in Morrissey Boulevard. For decades, there has been a disconnect between the Columbia Savin Hill neighborhoods to the water and this project has the potential to open the connections to the waterfront for residents. Without these transportation improvements, we on that side of Kosciuszko Circle will be stuck. With this development, there is an opportunity to construct both on and off-site affordable and workforce housing, while creating economic opportunities through workforce development and job training for residents. Dorchester Bay City can enhance open space and access to waterways, while incorporating climate resiliency measures and protections from the future of sea level rise on Columbia Point.

Frank Baker Boston City Councilor, District 3It is within this context that I was honored to welcome and speak with the Harvard Graduate School of Design studio led by Andrea Leers. Although the studio approached a slightly different site boundary and introduced new ideas about programming the site, the fundamental goals of the DBC project were met and exceeded through the dedication and creativity of the students and instructors. Through analysis and comparison with other innovation and enterprise districts as well as a close examination of the site constraints, the students developed original ideas that enhance our thinking about the site. Many thanks to the students and instructors for having closely engaged with and inspired us.

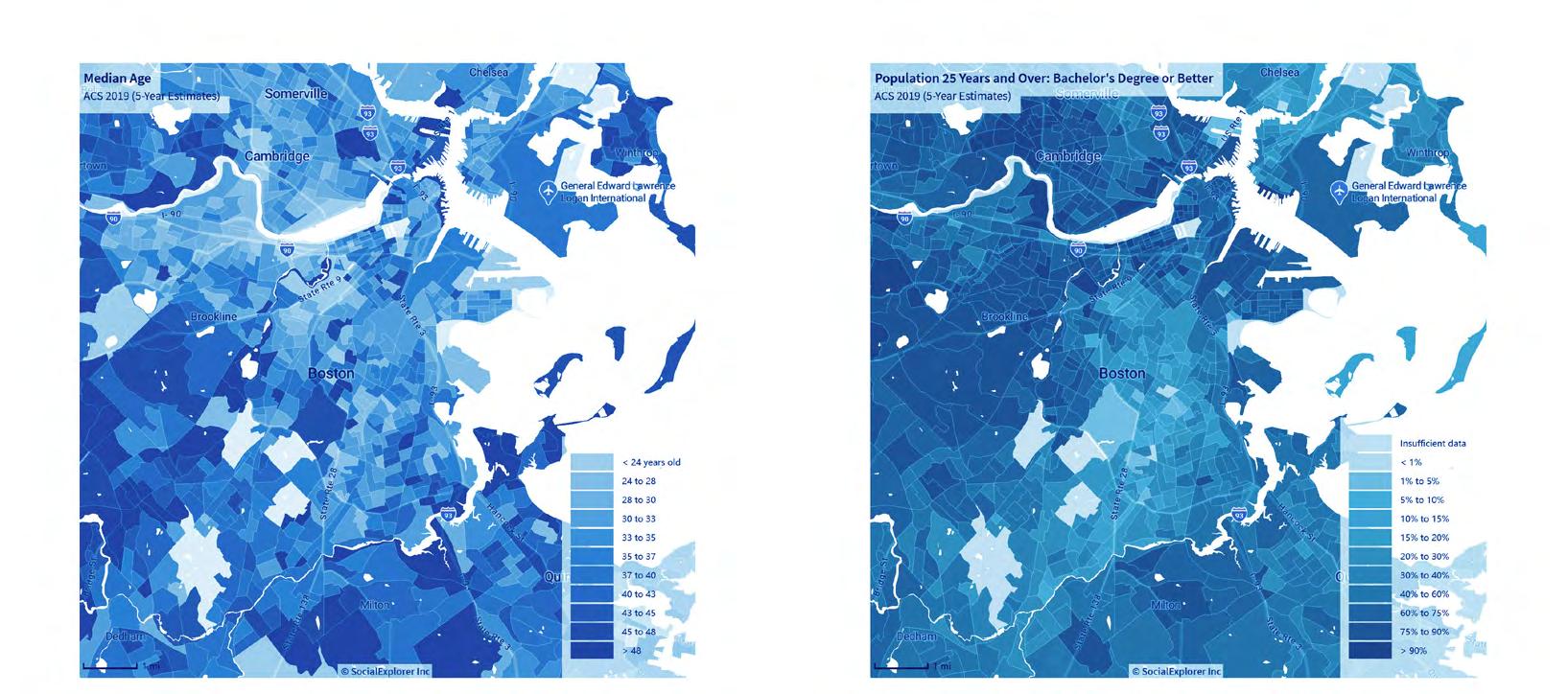

For the past ten years, the Boston metropolitan area has seen explosive growth due to its global attraction as a center for technology innovation. Development for “meds and eds” (major hospitals and research institutions) is fueling enterprise districts such as Kendall Square, the Seaport, and the planned Allston Enterprise campus. The challenges each district face center on keeping them attractive and welcoming for all, providing access for jobs and housing to surrounding communities, and maintaining the quality of urban design for which Boston is justifiably admired.

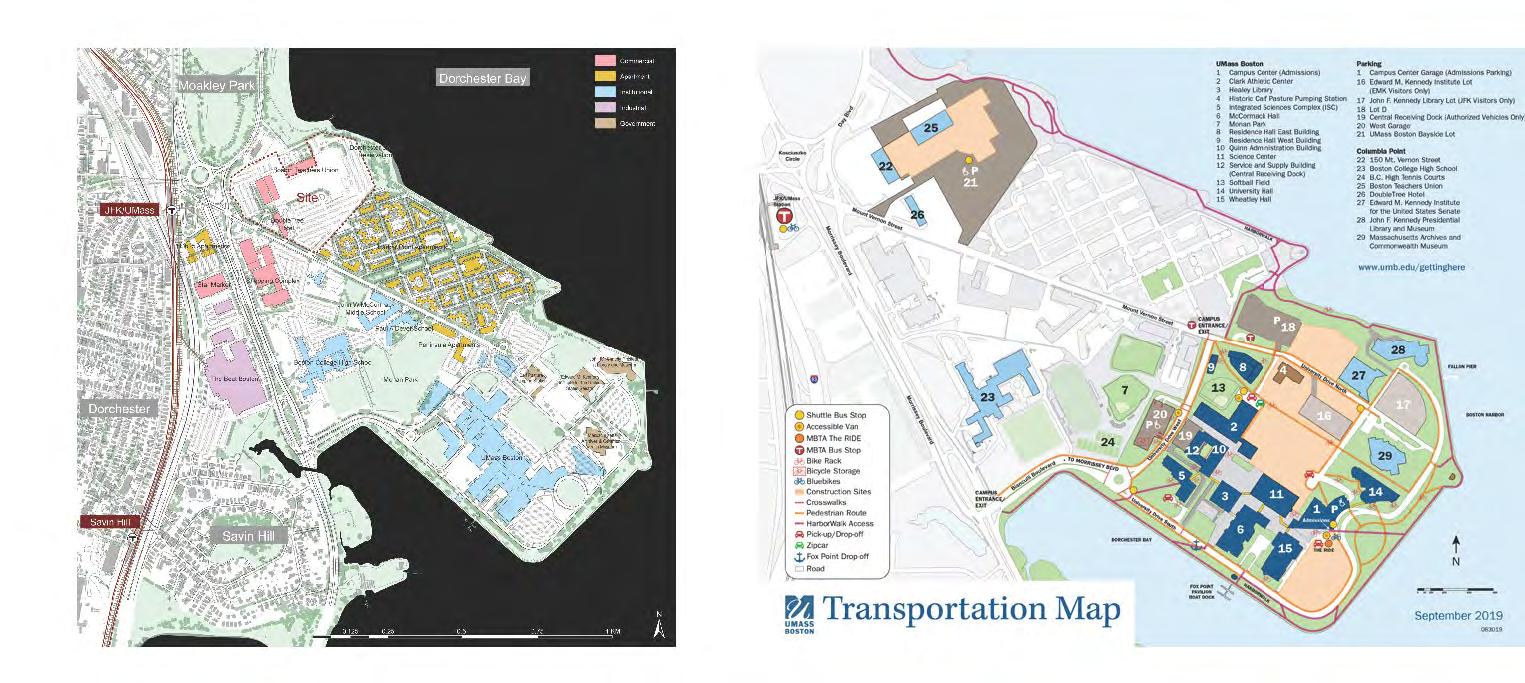

Site Background and Goals

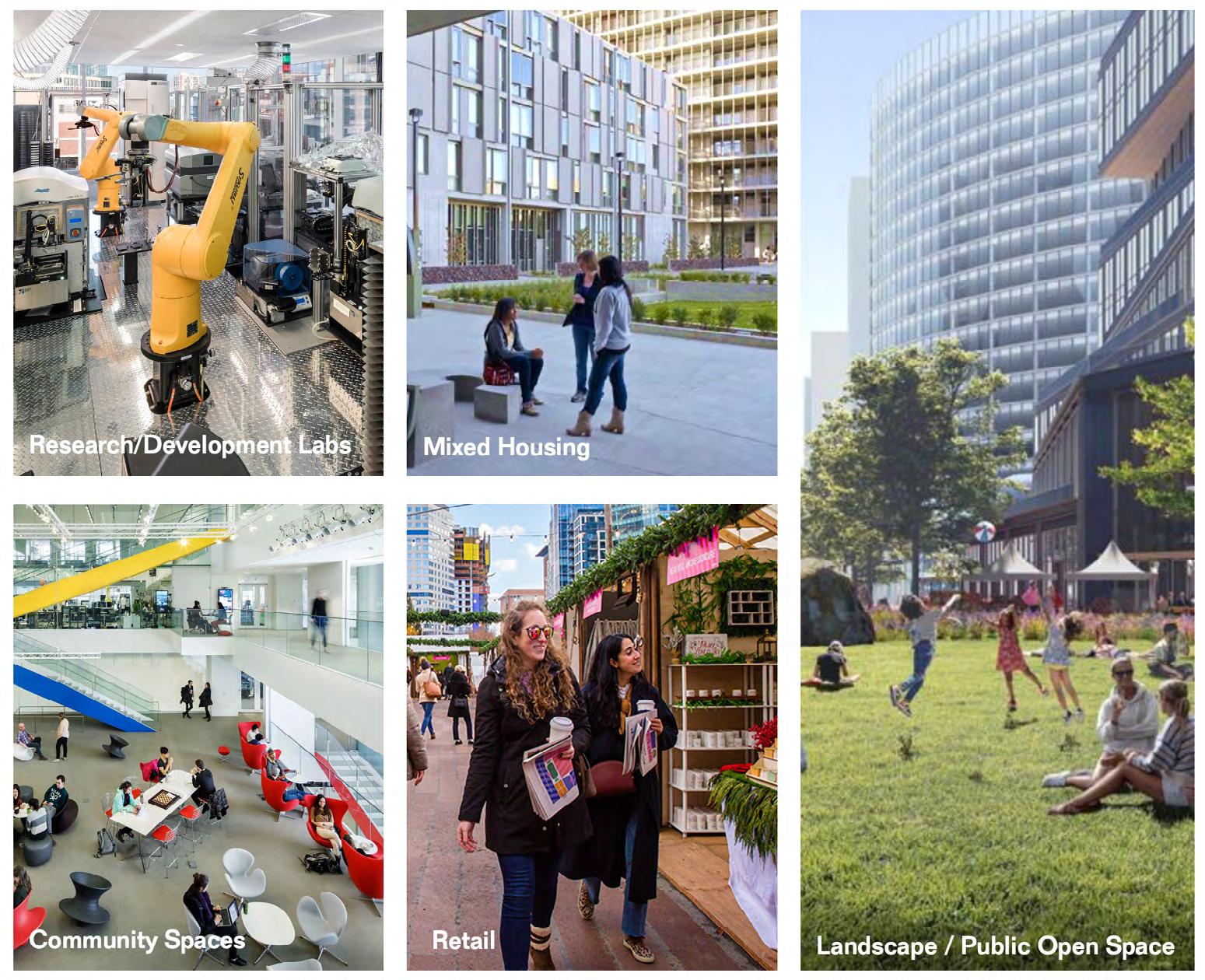

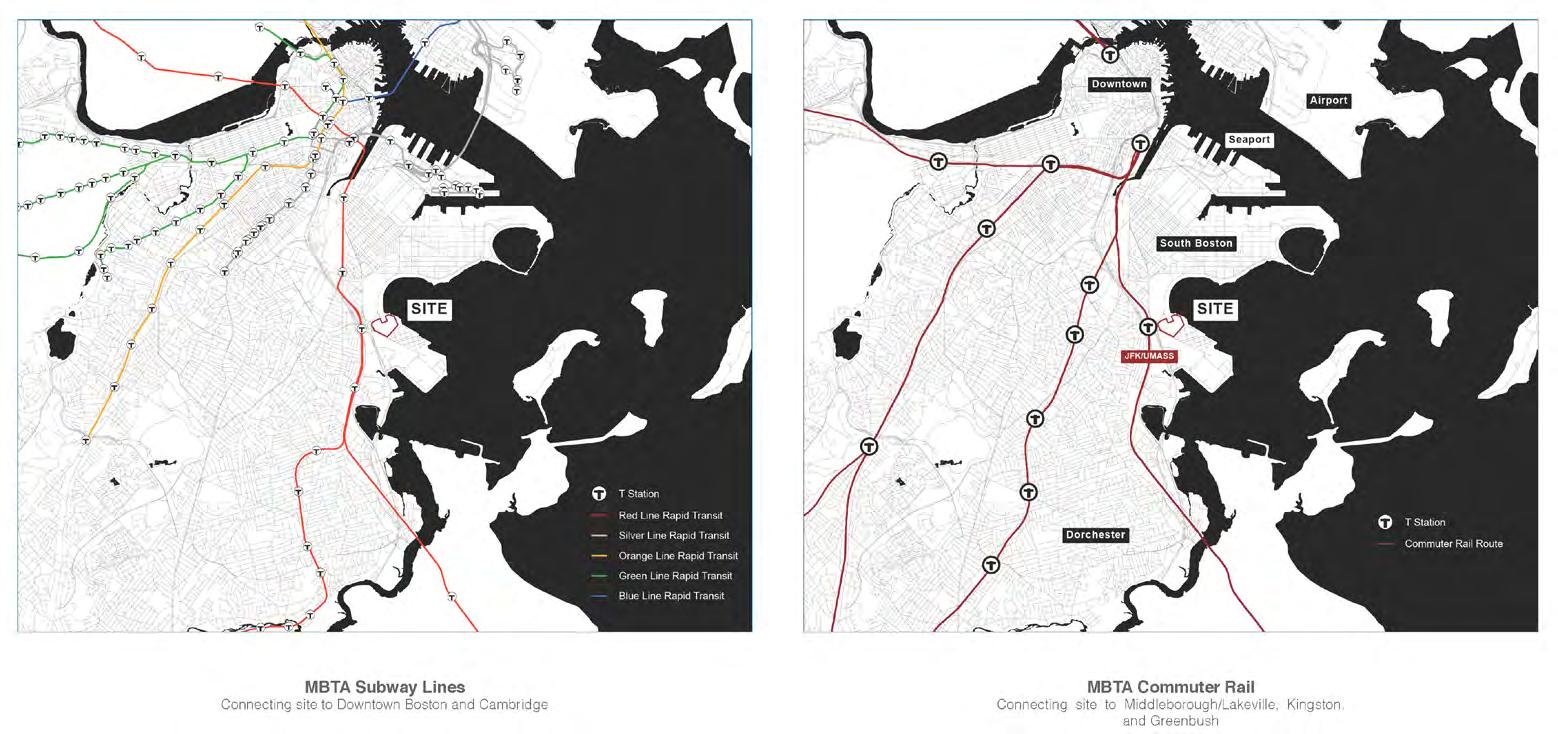

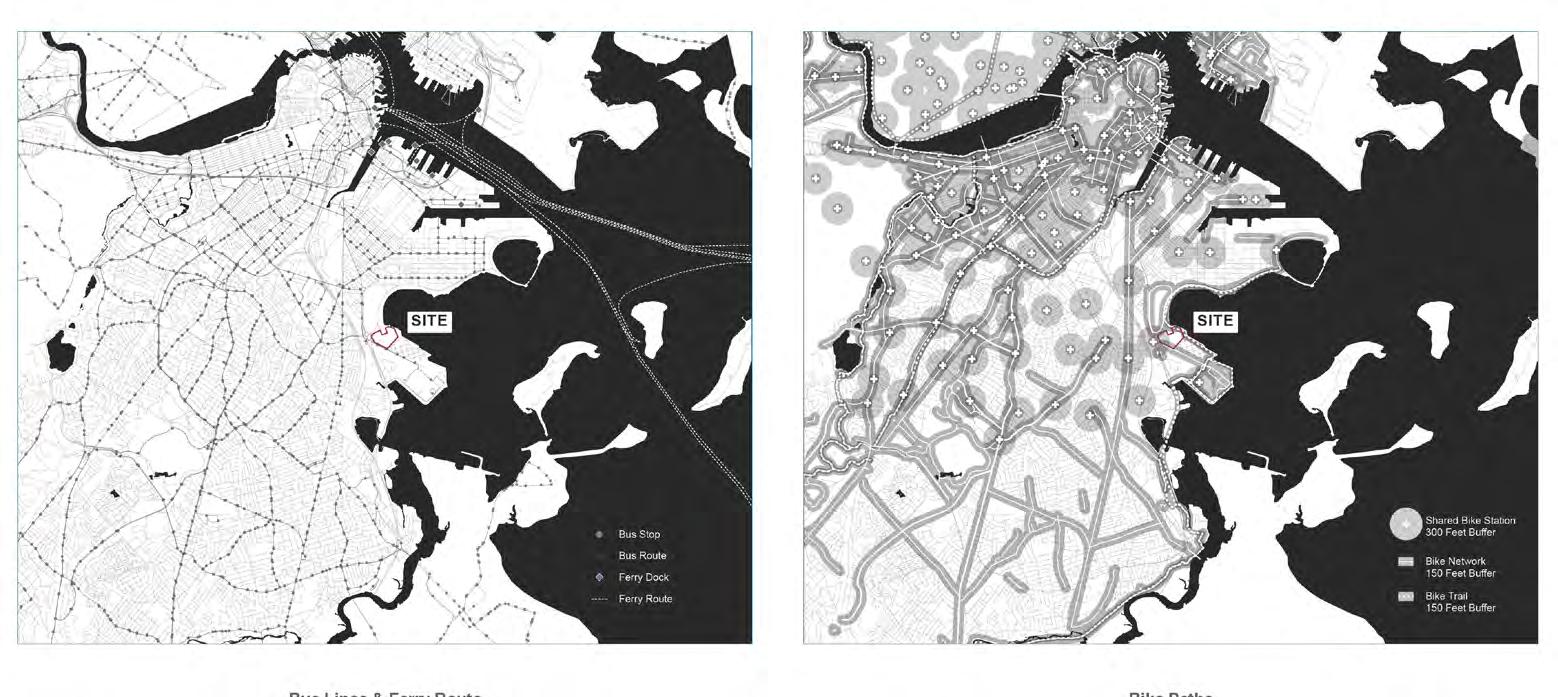

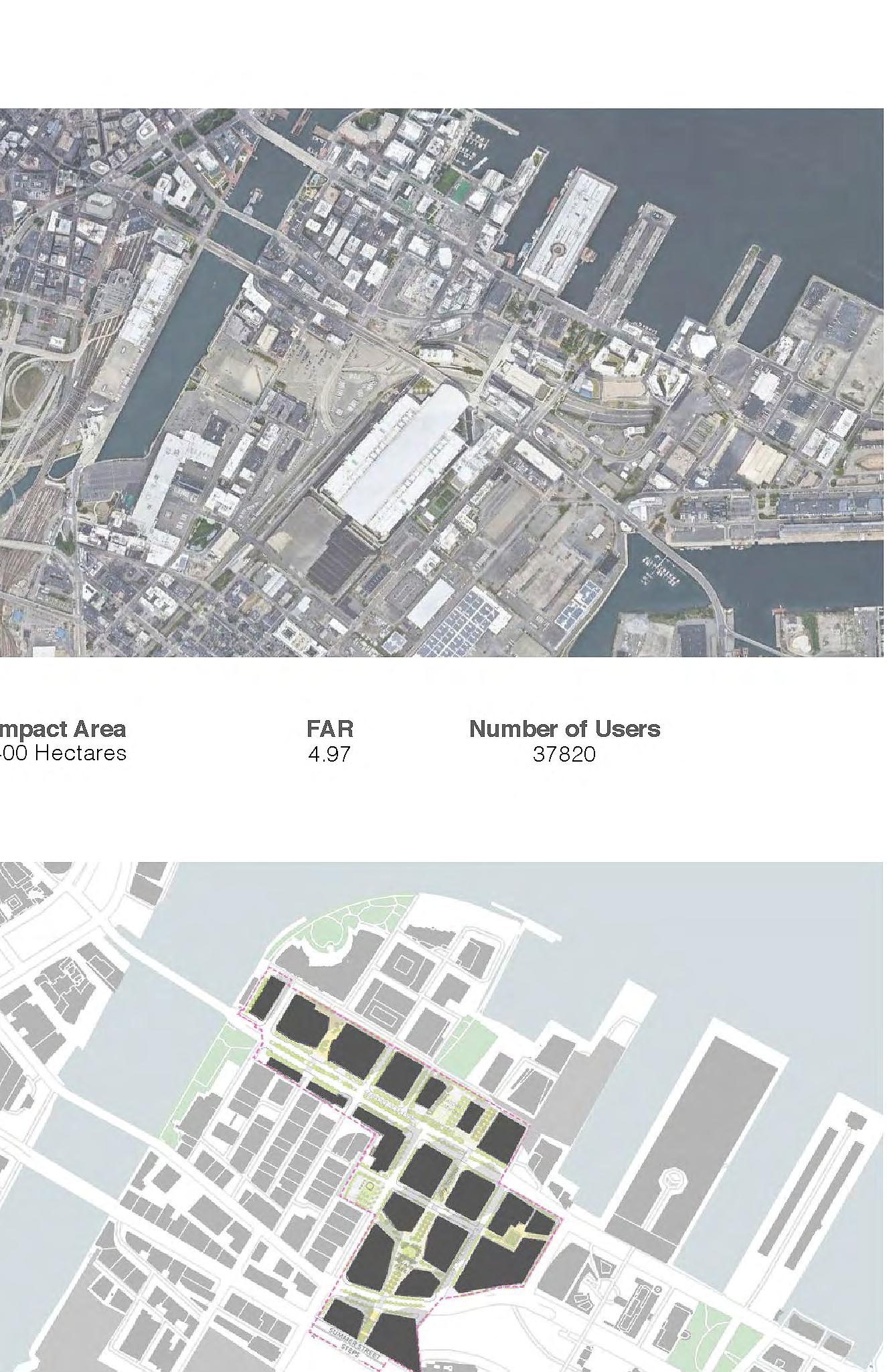

Our site for developing a mix of R+D lab space, housing, retail, and community services was a 25-acre parcel of land immediately adjacent to the JFK red line station, where metro, commuter rail, bus, and bikeways all make it extraordinarily accessible. Facing Dorchester Bay and the Harbor Walk, the site is part of the Columbia Point Peninsula—the home of UMass Boston, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, the Edward M. Kennedy Institute for the United States Senate, Boston College High School, and the Massachusetts Archives. Presently containing approximately 1,300 surface parking spaces, the site is underutilized and adjacent to vacant development sites owned by private parties, as well as a low-scale office building and a hotel. Responding to issues of resilience and flooding was key to imagining the potential of this landfill site. The goal of the studio was to unlock the potential of this extraordinary site to provide economic opportunity through employment, access to services, new community facilities, and connecting the neighborhoods to the water.

In contrast to an insertion or transformation of an established urban fabric, our studio in Dorchester Bay explored strategies for the creation of a new urban fabric; integrating the architectural, urban, and infrastructural scales. It sought to incorporate public transportation, open space, and mixed program zones into a viable urban district. Deliberate shifts in scale of study between site and building advanced understanding of the integral relationship between large territorial thinking and the design of specific structures.

Site

25 acres

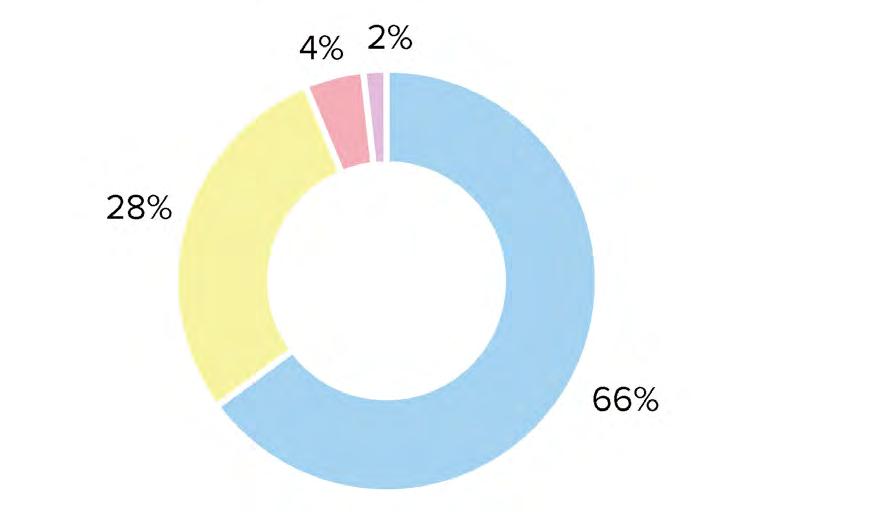

The site program contains a mix of research and development labs, mixed housing typologies, community spaces, retail, and landscape/open space. Approximately 75% of the total program will be the anchor (R&D lab space and its supporting functions (offices, open work space, administration and support). The below breakdown illustrates a general guiding framework for students, assuming the as-of-right F.A.R. of 2. Students were encouraged to explore higher densities for viable development.

The integration of program is critical; particularly how the anchor programs of an innovation district (research and development labs and offices) integrate with housing and community programs. This close integration of program is key to defining an urban district, and importantly, making an innovation and enterprise district a good neighbor to adjacent neighborhoods, the city at large, and the greater metropolitan region.

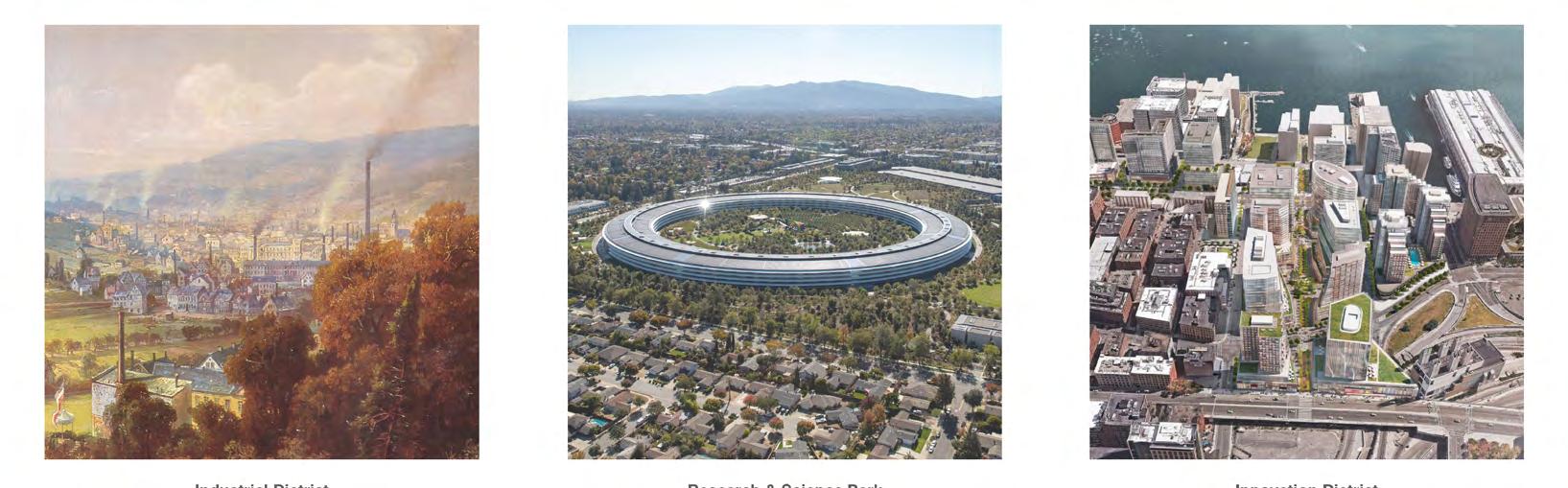

“Innovation and Enterprise Districts,” as they are commonly known in the United States, are a recent product of the market and not a well-established urban type. As the United States has emerged from the Great Recession, a new typology of urban development has shifted the spatial geography of “innovation” away from suburban corridors of spatially isolated business campuses accessible only by car, having little attention placed on quality of life or any integration of work, housing, and recreation, and back toward urban centers. Characterized by Brookings Institute researchers as “geographic areas where leading-edge anchor institutions and companies cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators, and accelerators,” such districts are physically compact, accessible to transit, and offer mixed use housing, office, and retail program.

Following a long history of 19th and 20th century industrial districts, company towns and later technology campuses, enterprise and innovation districts are described by a Brookings Institute published a report in 2014 as “the manifestation of mega-trends altering the location preferences of people and firms, and in the process, re-conceiving the very link between economy shaping, place making, and social networking.” [1]. From coast to coast, these concentrations are generating economic development and a resultant building boom around knowledge-intensive sectors of the economy. Innovation districts are delivered and advocated for by a varied composition of leaders in the United States and abroad. Brookings identifies mayors and local governments as the primary drivers, citing former Boston Mayor Tom Menino, along with Joan Clos of Barcelona and the municipal government of Stockholm.

Additionally, real estate developers and land owners form critical partnerships with anchor companies, such as Amazon in Seattle’s South Lake Union and Quicken Loans in Detroit. The report also cites the importance of non-profits, NGO’s, community groups and other philanthropic partners to advocate for equity and community services. The future of design in such districts is thus collaborative and situating; global in reach yet highly local in impact. They leverage the distinct economic, cultural, and geographic strengths of their location. As such, innovation districts have the exciting potential to leverage distinctive place characteristics along with global economic trends to shape more accessible and equitable future cities.

“Innovation districts are still an early trend that, because of their multi-dimensional nature, has yet to receive a systematic analysis. Yet we believe that theyhave the unique potential during this pivotal postrecession period to spur productive, inclusive, and sustainable economic development.”Andrea P. Leers, Anthony Averbeck

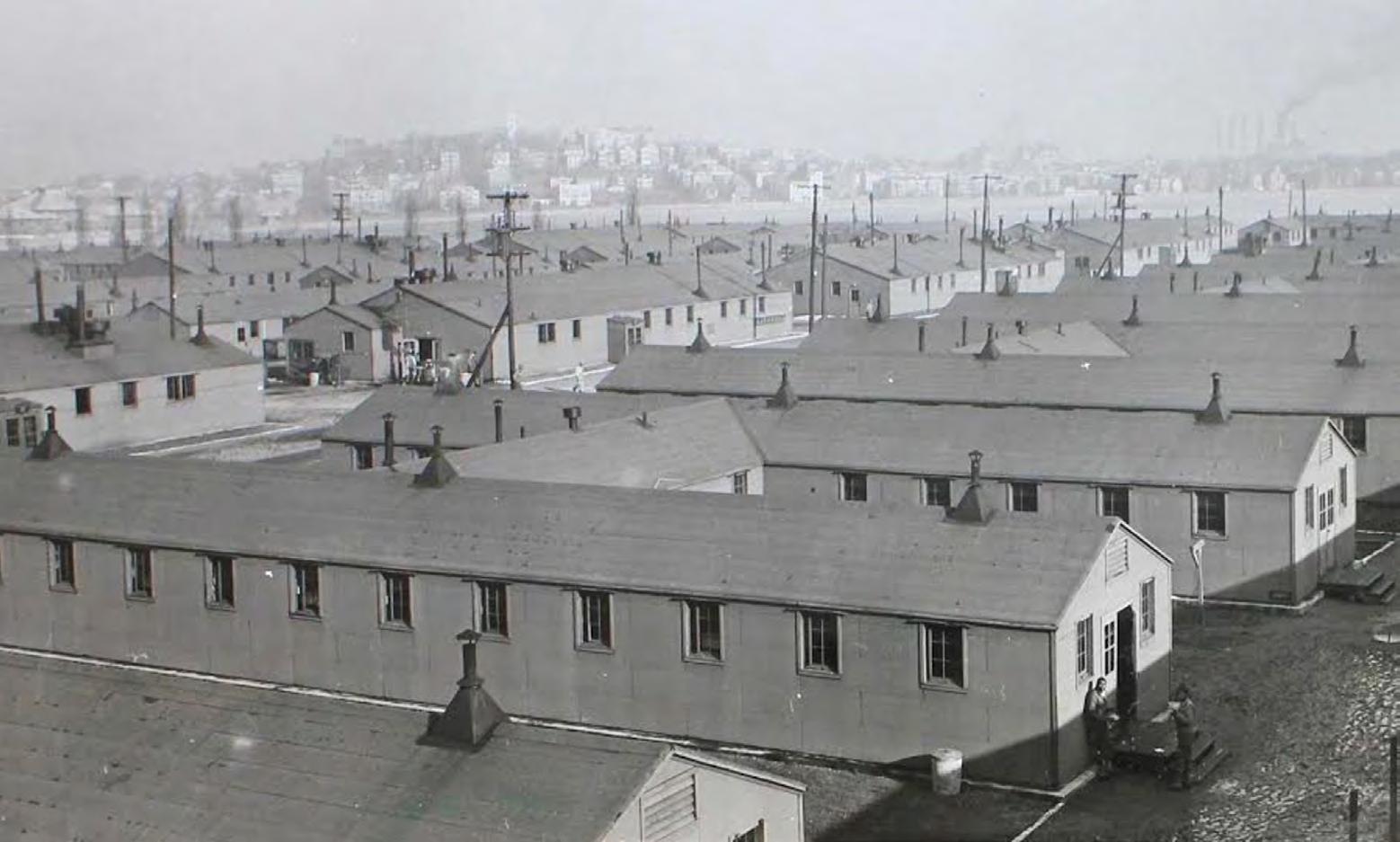

The land presently known as Columbia Point, a peninsula extending off the mainland of the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston, was the landing place for Puritan colonizers in the early 1600s. It was known by the indigenous Massachusett peoples as “Mattaponnock,” and was where settlers brought livestock to graze. Over time, it was used as a trash dump and pumping station for the growing metropolis. Despite sparse land use, major infrastructural arteries and basic utlities were extended onto the site, as can be seen in the photo at left from ca. 1920, in anticipation for the site’s future development.

During the Second World War, the site began a second life as an internment camp for Italian prisoners of war, with legions of barracks constructed across the open site. The barracks were dismantled by 1960 (see aerial photograph on pages 26-27), when subsidized housing was constructed on the site. These housing blocks were later retrofitted and replaced by the Harbor Point mixed housing that remains on Columbia Point, leaving a portion of the site for commercial development.

In 1967, a 275,000 s.f. shopping mall was constructed on the site, featuring major retail tenants Woolworth, Zayre, and Stop & Shop among others, with a large accompanying parking lot. Due to crime and low sales, the mall closed just five years later in 1972. The building would remain vacant for a decade until it was converted to the “Bayside Expo Center,” which opened in 1983 following a $15 million redevelopment effort. Events and trade shows would be hosted at the complex for nearly three decades. The sign in the foreground of the photograph at right would remain, becoming a recognizable feature of the site for decades to follow.

The University of Massachusetts-Boston acquired the site in the 2010 and demolished the expo center building to make way for surface parking. The following year, the Boston Planning and Development Agency approved a 25-year master plan for Columbia Point. Several proposals for the site would follow, including the Olympic Village as part of Boston’s bid for the 2024 Summer Olympics. At the time of publication, the site remains surface parking; serving primarily as a commuter lot for students, faculty, and staff of the nearby UMass campus. Traces of the convention center’s foundations remain, a reminder of the city as palimpsest.

Housing Project on Morrissey Boulevard, Boston College High School on Columbia Point ca. 1960. Photo by Lenscraft Photos, Inc. for the FayFoto Boston photographs collection (1955-1964) to document cities and towns in New England. Source: Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. The studio site is where the foundations of the barracks are visible on the lower left corner of the image.

Housing Project on Morrissey Boulevard, Boston College High School on Columbia Point ca. 1960. Photo by Lenscraft Photos, Inc. for the FayFoto Boston photographs collection (1955-1964) to document cities and towns in New England. Source: Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections. The studio site is where the foundations of the barracks are visible on the lower left corner of the image.

Saad Boujane

Pinyang Chen

Danny Kolosta

Adriana Lasso-Harrier

Dianne Lê

Zhuoer Mu

Naksha Satish

The first two weeks of the studio were devoted to an analytical and investigatory component, in order to develop a springboard of knowledge from which to develop intervention strategies. A studio site visit during the first week informed the analysis. Research and documentation was divided into three tracts of investigation—the Dorchester Bay Site Area, Innovation District and Harbor Edge Precedents, and program components of the Innovation District (summarized below). This investigatory work was completed jointly with the objective of producing a studio-wide shared database and resource.

Microclimate conditions

Topography, hydrology, vegetation

Existing and historic land use and key recent alterations

Existing/ proposed mobility infrastructure/ site access (transit, bicycles, cars, pedestrians)

Existing urban design guidelines

Analysis include district framework, street system, open space network, architectural language, figure/ground comparisons with the Dorchester Bay site area. Possible examples of study include but are not limited to the following:

Seaport Square, Boston

Kendall Square, Cambridge

Assembly Square, Somerville

Harvard Enterprise Research Campus, Boston

South Lake Union District, Seattle

the Innovation District

Overview of the component institutions

Graphic display of programmatic elements

Development of proposed innovation district programs

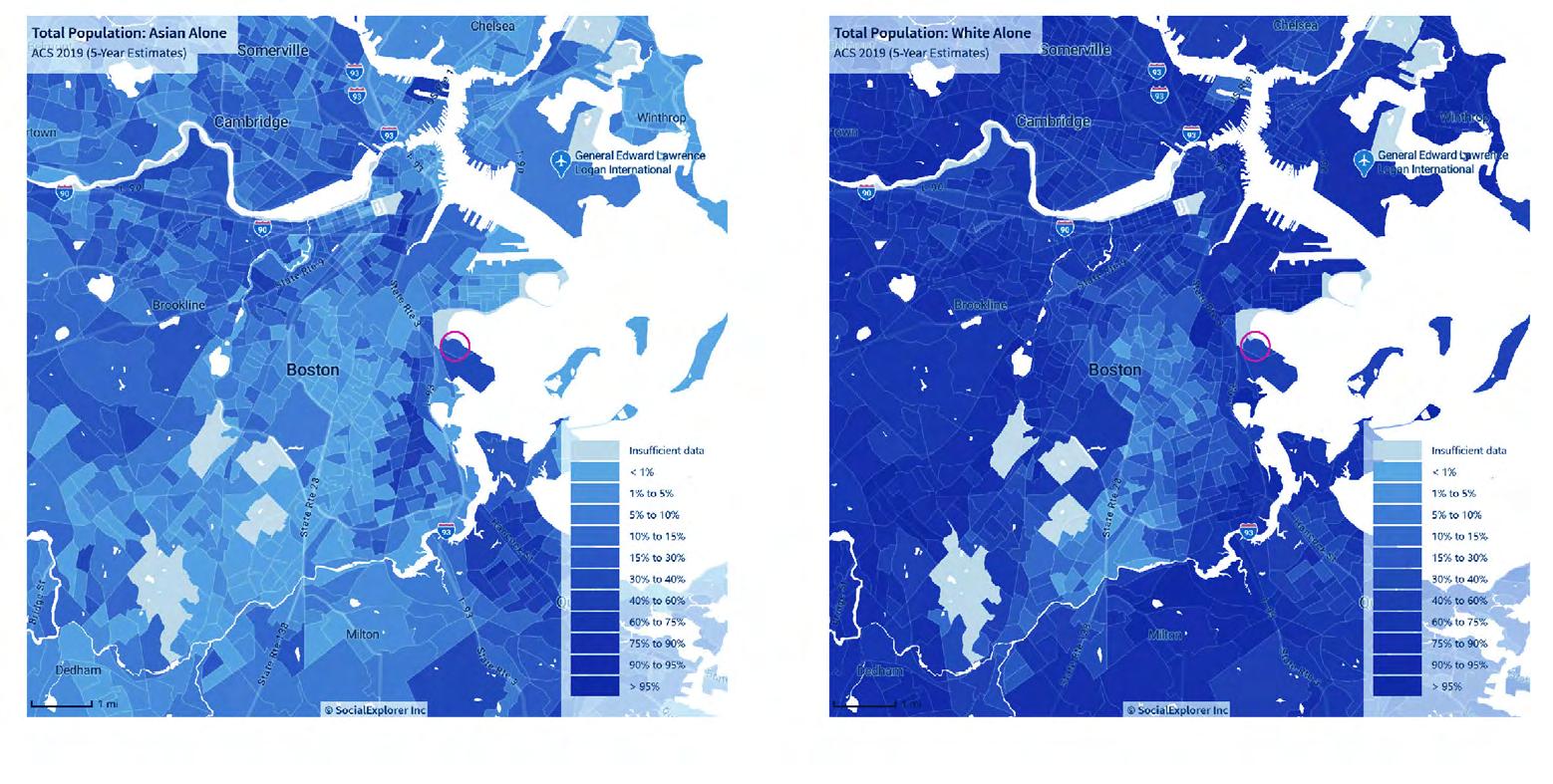

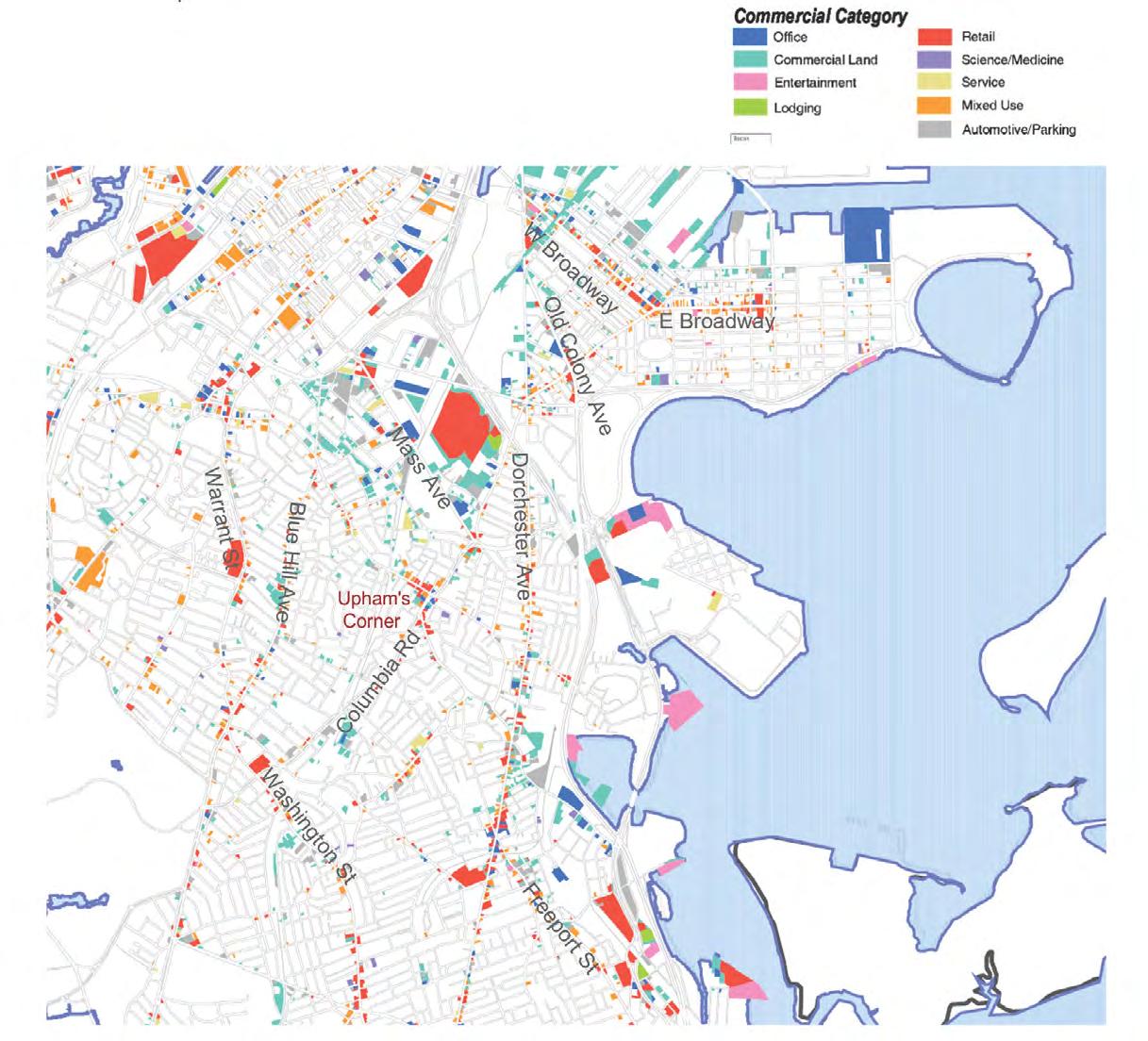

Our site is a 25-acre parcel of land immediately adjacent to the JFK/UMass red line station, where metro, commuter rail, bus, and bikeways all make it extraordinarily accessible. Facing Dorchester Bay and the Harbor Walk, the site is part of the Columbia Point Peninsula—the home of UMass Boston, and the JFK Library. Responding to issues of resilience and flooding will be key to imagining the potential of this landfill site. Through mapping and ethnographic research, we identified the following key opportunities and challenges for the site:

Multimodal access to public transportation

Connection to the waterfront and the greenway network

Adjacency to educational facilities

Proximity to diverse neighborhoods

Resilience and flooding

Infrastructure and walkability

Community facilities and retail space

Data Source: Alex Krieger and David Cobb with Amy Turner, “Mapping Boston” (2001)

Roads and Bridges

Infrastructure and Walkability

The following research questions inform our understanding of innovation districts and their relevance in shaping the contemporary city. An historical typological analysis follows.

What is the history of the typology?

What variants of the typology exist globally? How have these different types related to larger urban and regional planning movements and theories?

What are the programmatic components that make up an innovation district?

Innovation Districts are the confluence of academic institutions, research and practice industry and society to enable stronger exchange and promote sustainable holistic growth of communities.

Innovation districts are intended to help spur job growth by creating places where people can share ideas and establish new and innovative businesses.

Saad Boujane, Adriana Lasso-Harrier, Naksha Satish

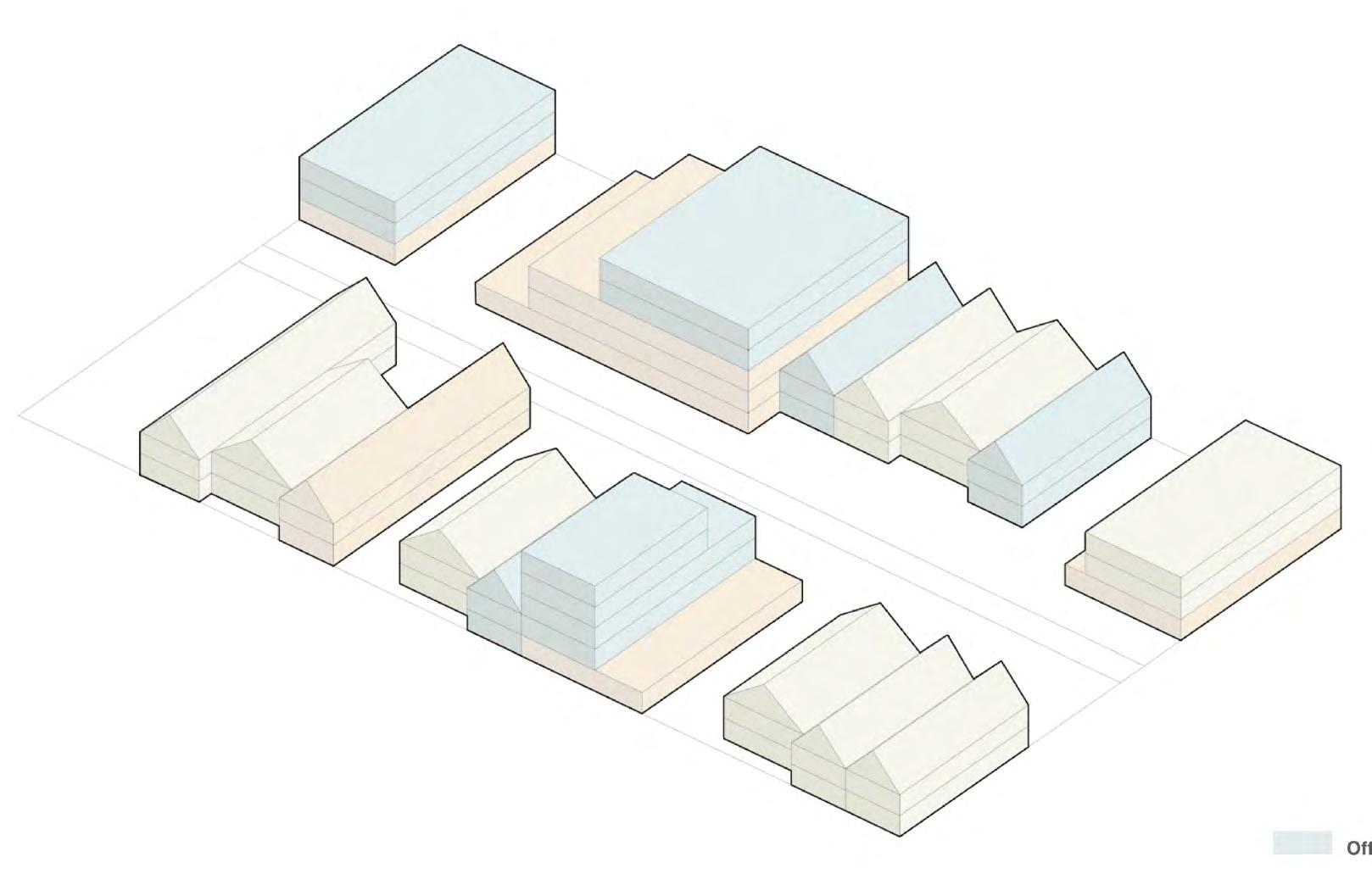

Recreational: 2,000 sqft

Office/R&D: 1,170,000 sqft

Housing: 530,000 sqft

Retail: 235,000 sqft

Academia: 320,000 sqft

Block Area: 680,000 sqft

FAR: 3.29

Adriana Lasso-Harrier, Naksha Satish, Saad Boujane

Recreational: 2,000 sqft

Office/R&D: 1,170,000 sqft

Housing: 530,000 sqft

Retail: 235,000 sqft

Academia: 320,000 sqft

Block Area: 680,000 sqft

FAR: 3.29

Adriana Lasso-Harrier, Naksha Satish, Saad

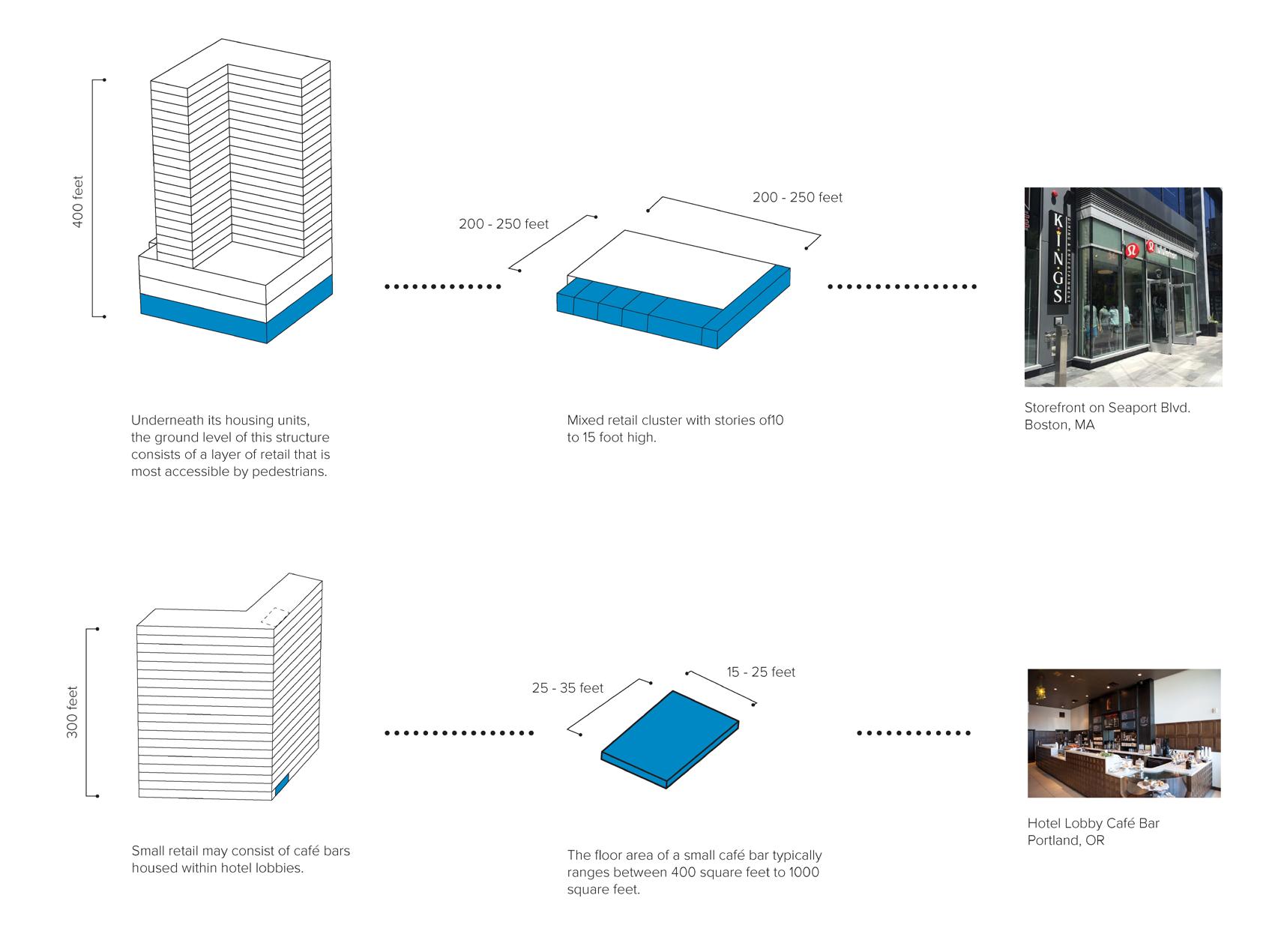

Like Harbor Point, the Seaport was a waterfront tabula rasa, cut off from the rest of Downtown Boston by dilapitated bridges and an above-grade highway (pre-Big Dig). The Seaport provides an inspiration for how to leverage private capital, powerful innovation driver companies, and creative activation of the public realm in order to create Boston’s “newest neighborhood” seemingly from nothing. But the Seaport has received extensive criticsim for its inability to meld to the greater South Boston neighborhood, its expansiveness/lack of inclusivity, and developments that are at high risk of flooding.

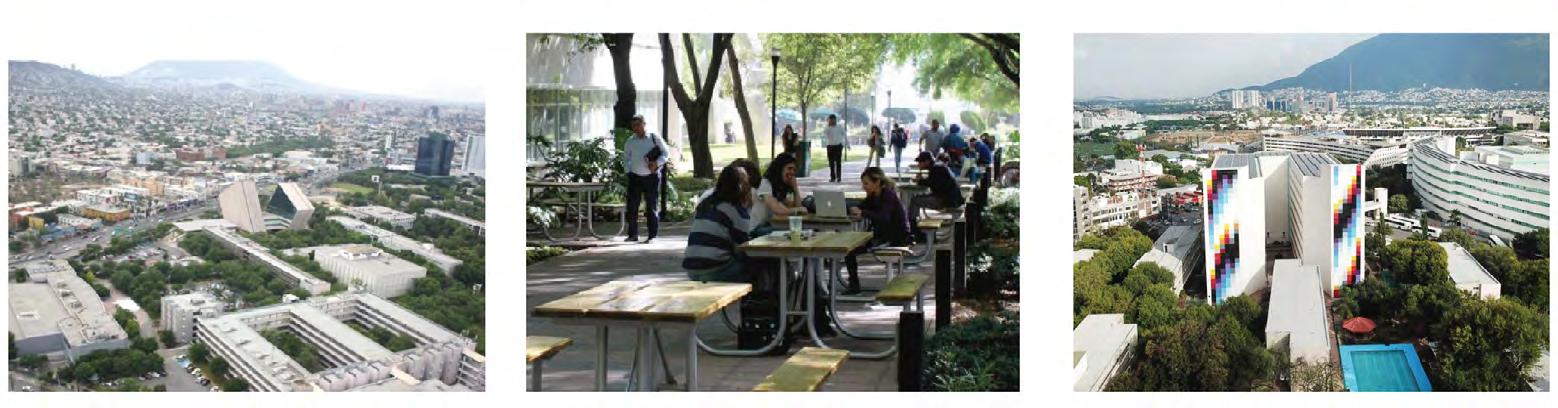

DistritoTec exemplifies how a nearby university can drive planning at a district level, rather than merely within its own campus. Spurred by violence that affected its students and the City of Monterrey overall, Tec University used its influence, capital, and centrality to solve issues of connectivity, street safety, and neighborhood representation. The result was a campus that shed its walledoff structure to one that knit the neighborhood together.

Residents of Pittsburgh’s Uptown neighborhood had endured decades of disinvestment and decline -- but found their voice through the extensive community engagement that informed the plan for the Ecoinnovation District. As we make our own plans and design our own site this semester, we can learn how planners addressed community complaints about traffic, pollution, and pedestrian safety within their vision for a more environmentally and economically friendly Uptown.

University for the Common Good

A Campus Block Morphology

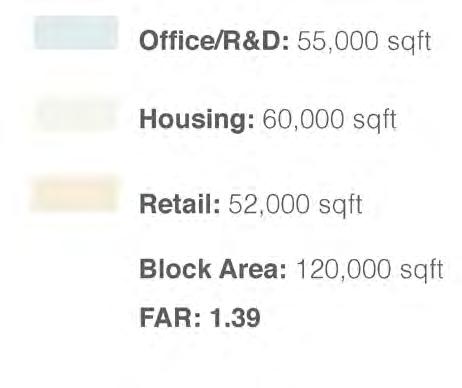

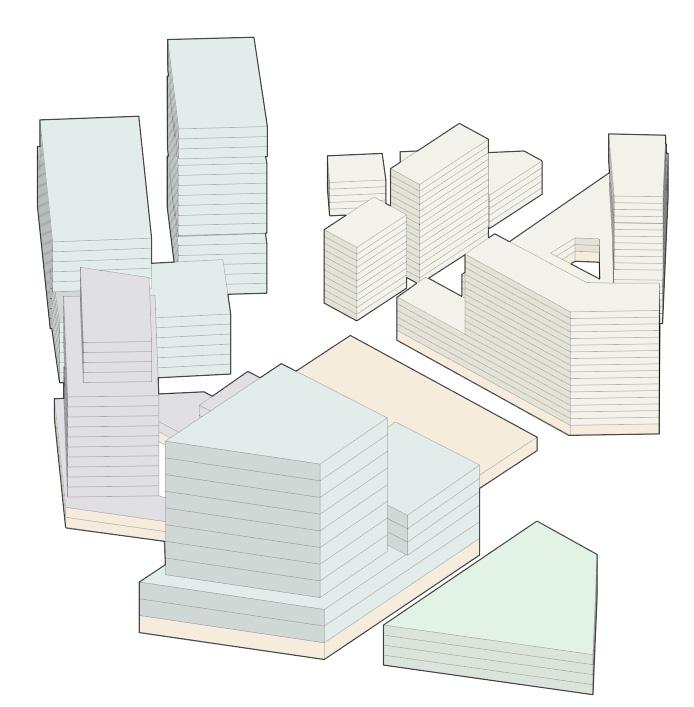

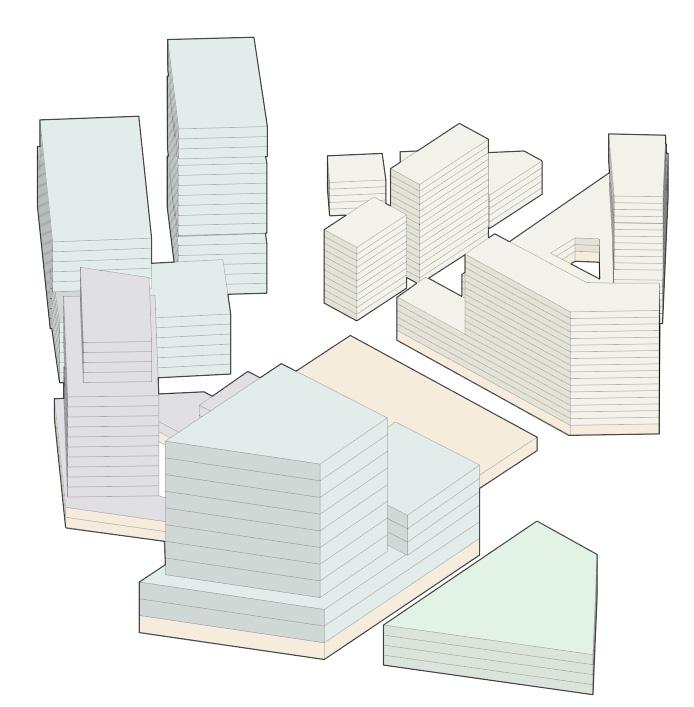

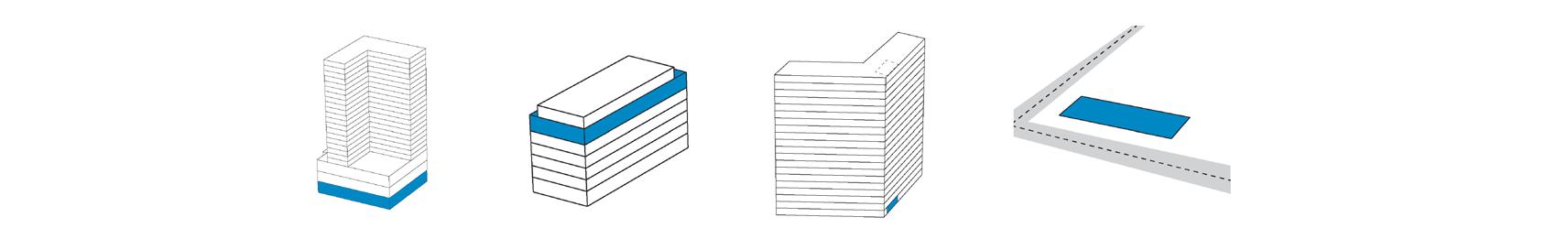

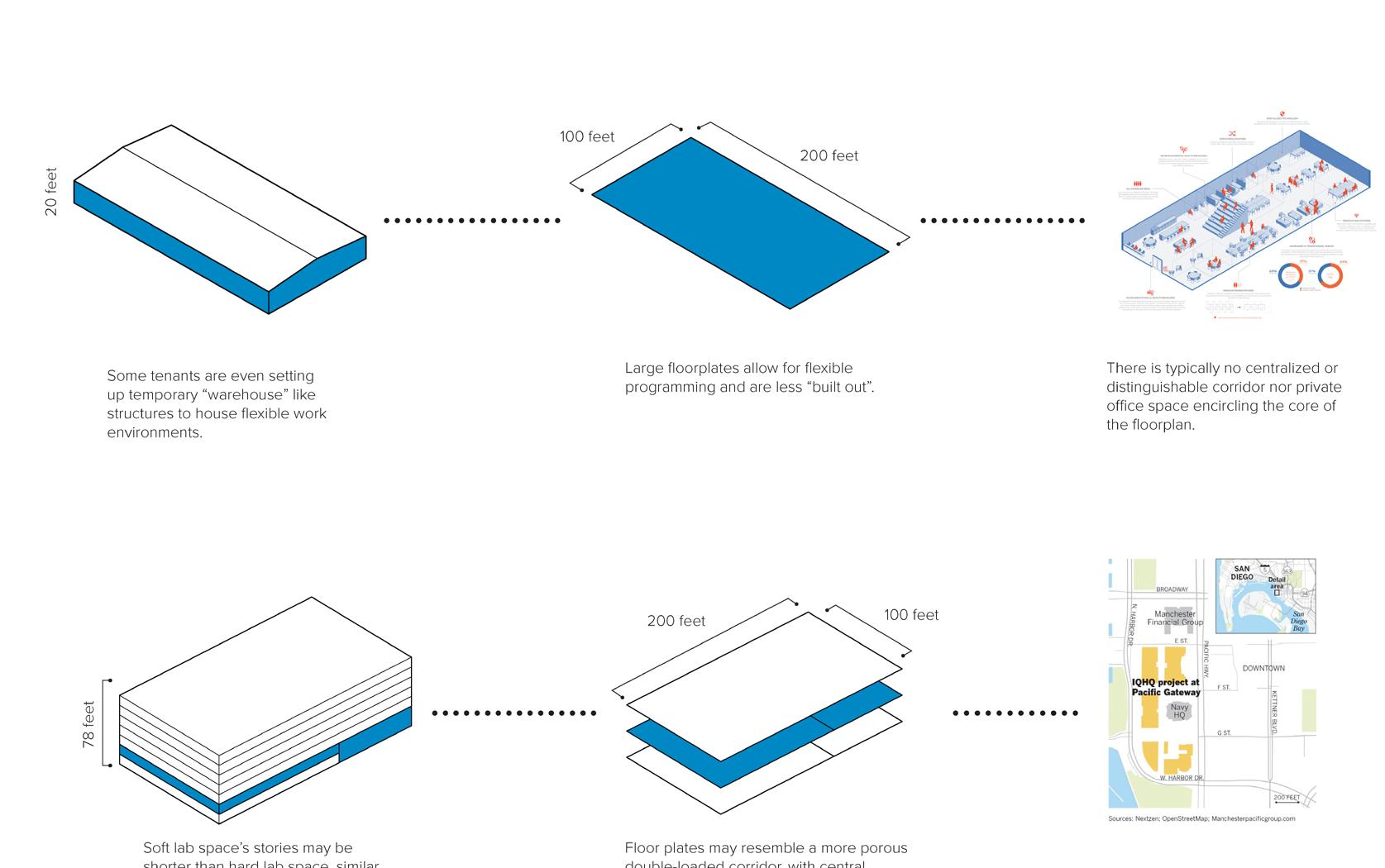

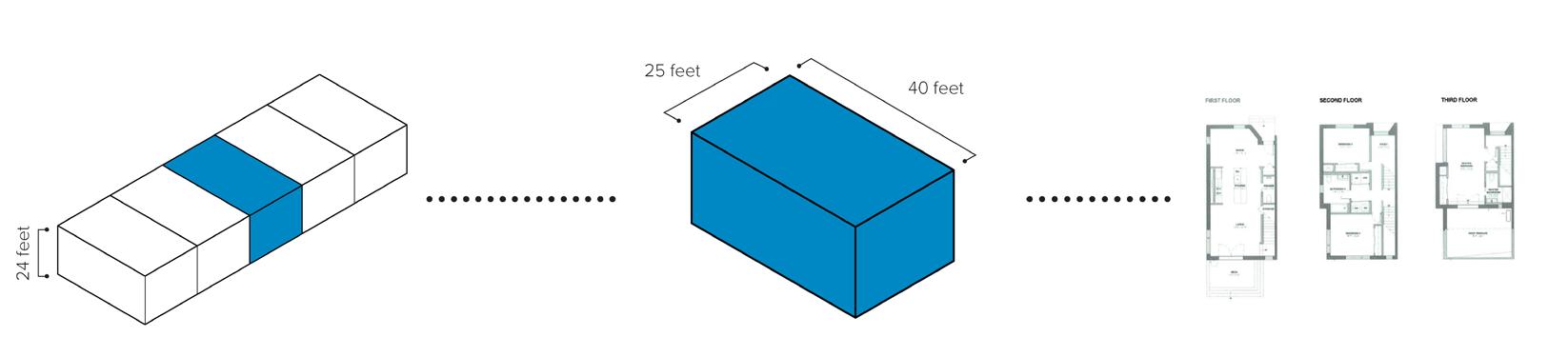

This research tract of phase 1 seeks to catalogue development typologies that typify an innovation district. While typologies among various innovation districts may be nuanced, certain core components exist: commercial, housing, community, retail, and open space uses. We investigated the characteristics of the parts that comprise the whole so that design teams could access this catalogue as a repository of data to leverage when planning and designing their sites. One key discovery was the increasing emergence of innovation district hybrid development typologies that fuse two or more uses together, and transcend the traditional mixed use development.

Programming Components

Parts of the Whole

Commerical Anchors

Collective Housing

Community Engagement

Open Space (Public)

Office Tower (highest density)

Medium-Density Office Buildings (12-14 stories)

Single-Story Free Plan Office Buildings

Soft Lab v. Hard Lab Space (shorter floor-toceiling heights)

Walk-Up

Townhouse Apartments

Low/Medium Density Apartments

Low/Medium and High Density Mix

Museum Lab, Pittsburgh

(Adaptive Reuse)

Superkilen

Copenhagen, Denmark BIG, Superflex, Topotek

Suffolk Downs

Boston, MA

Stoss Landscape Urabanism

Open Space Core for an Evolving City

Guangzhou, China Platform Design Associates

Harbor Way

Boston, MA

James Corner Field Operations

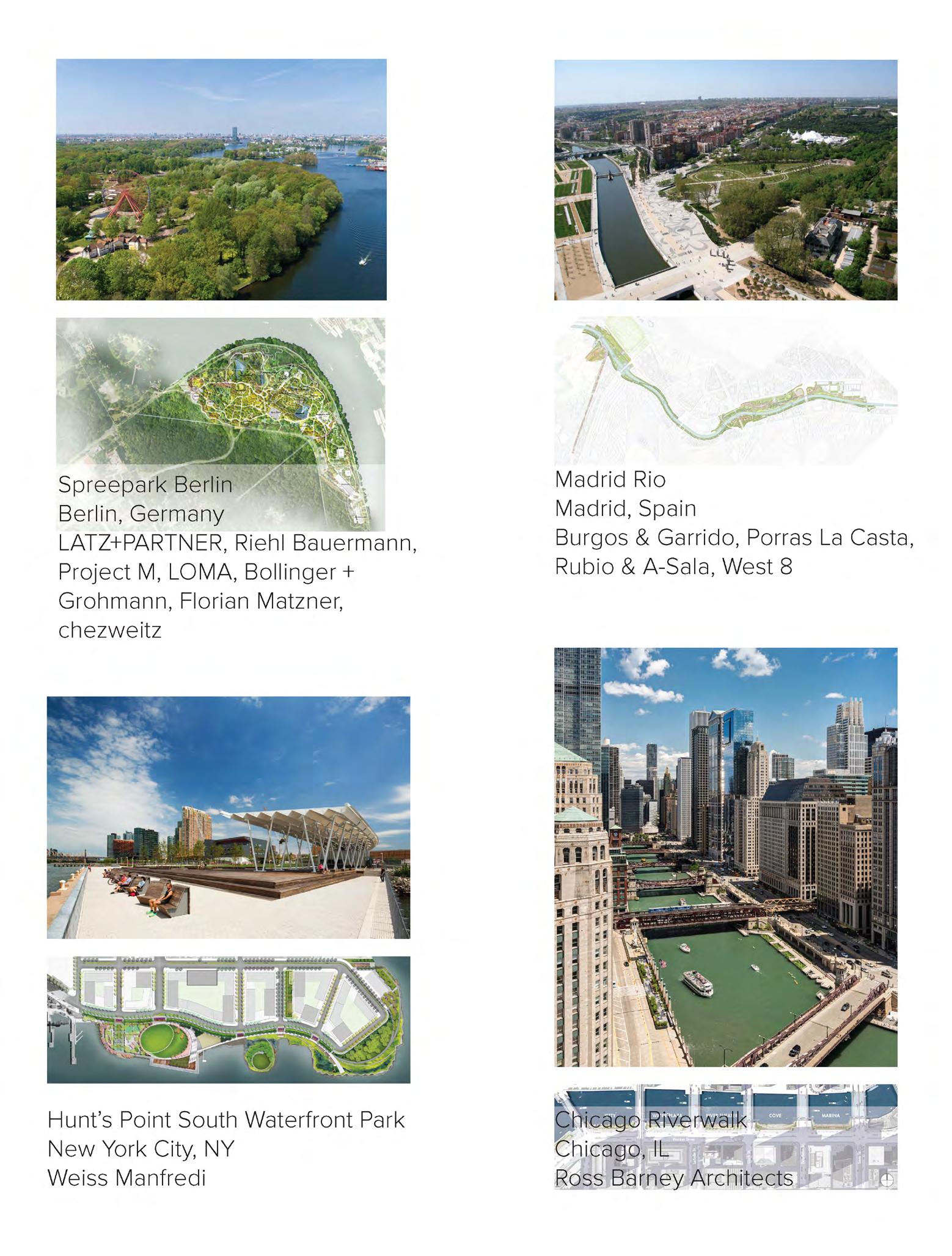

Spreepark Berlin

LATZ+PARTNER, Riehl Bauermann, Project M, LOMA, Bollinger and Grohmann

Madrid Rio

Burgos and Garrido, Porras La Casta, Rubio & A-Sala, West 8

Hunt’s Point South Waterfront Park New York, NY

Weiss Manfredi

Chicago Riverwalk

Chicago, IL

Ross Barney Architects

Columbia Point Public Housing Project, 1966.

Photograph by Grant Spencer.

Source: Digital Commonwealth

Columbia Point Public Housing Project, 1966.

Photograph by Grant Spencer.

Source: Digital Commonwealth

After the research and analysis of the Dorchester Bay site, precedents in innovation districts and harbor edge development, and analysis of possible programmatic elements, students worked in teams to develop an innovation district concept, informed by the realities of site and uses observed during the site visit. The goals of the site strategy phase were the following:

1 Develop a clear strategy for the innovation district precinct; its streets and public spaces; its new building and open space strategy; and its integration with existing structures, ecological conditions (i.e. the harbor), edges, etc.

2 Identify principal points of entry to the district, and clarify its boundaries with respect to the existing public housing, Columbus Park, and the harbor.

3 Define the role and placement of public facilities to catalyze community engagement and advance equity and inclusion (Boys & Girls Club, recreation center, etc.)

4 Consider an appropriate density for the district as a framework urban massing scheme, giving particular consideration to the scale of open spaces. Use the precedent studies as a guide to your proposals.

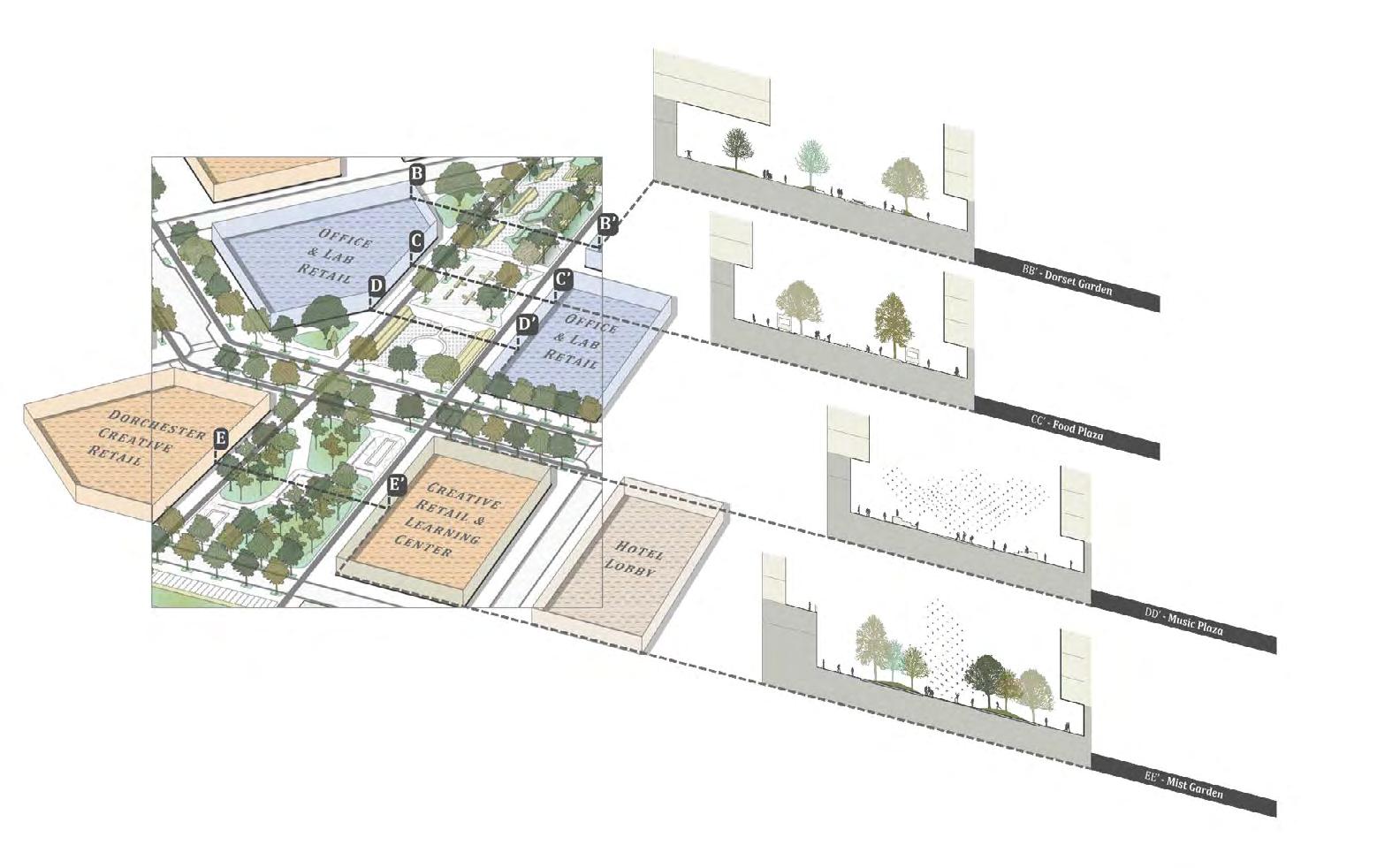

For the remainder of the semester, the teams tested their innovation district concepts through the development of architectural projects and their associated outdoor public spaces and the projects engaged issues of building form, materiality, access and entry, as weldl as programmed open space and ground material. Research and development labs and housing, along with a shared public facility such as a Boys and Girls Club or school – were the basis for this study, but other programmatic elements such as retail or dining services, were included, as they are central to the Innovation District concept. In the architectural and/or landscape development of a part of an urban district, the intent was to explore specific qualities which will contribute to the vibrant life of the place; drawing researchers, students, faculty, businesspeople and the community-at-large together for exchange and informal gathering.

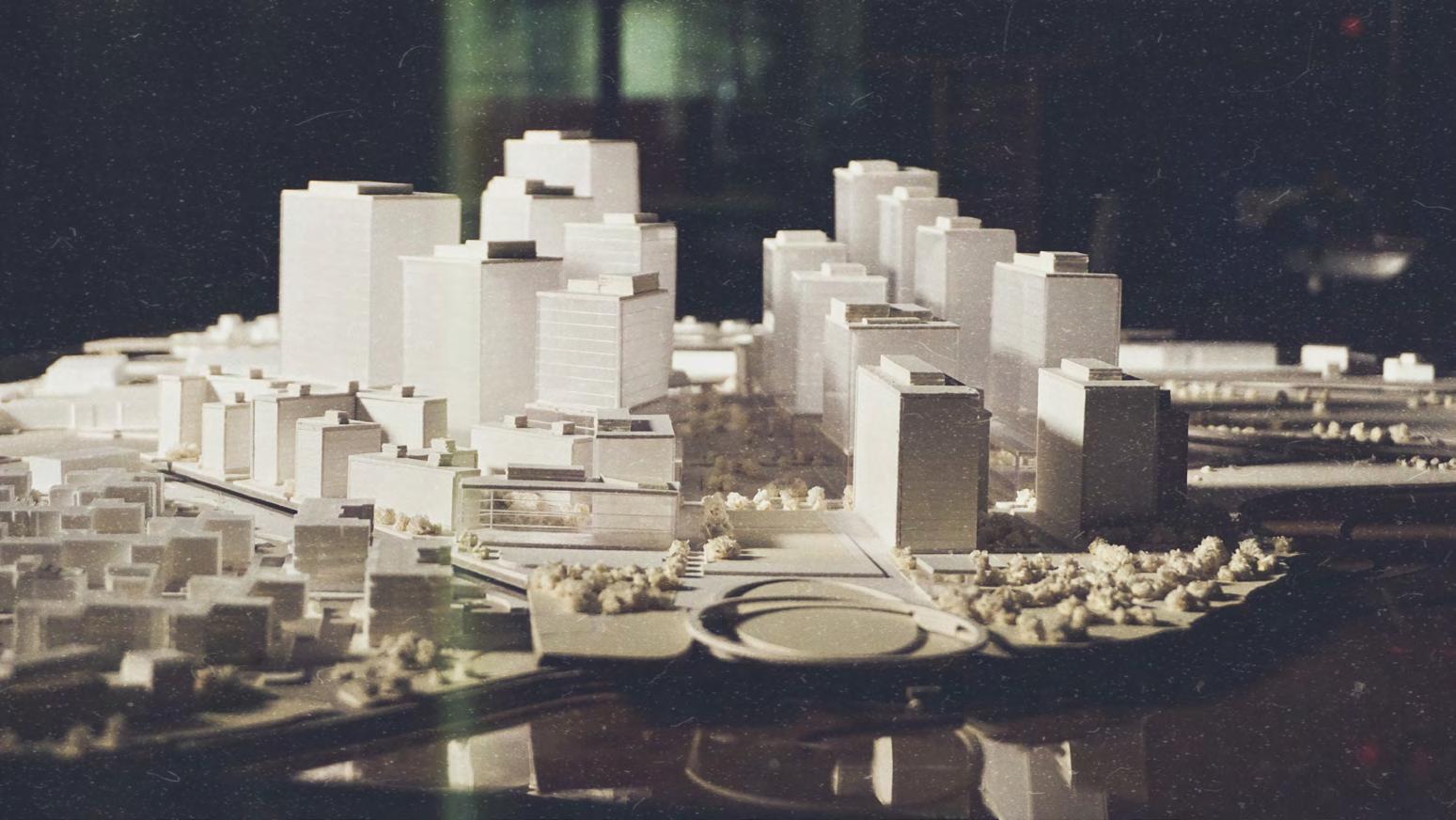

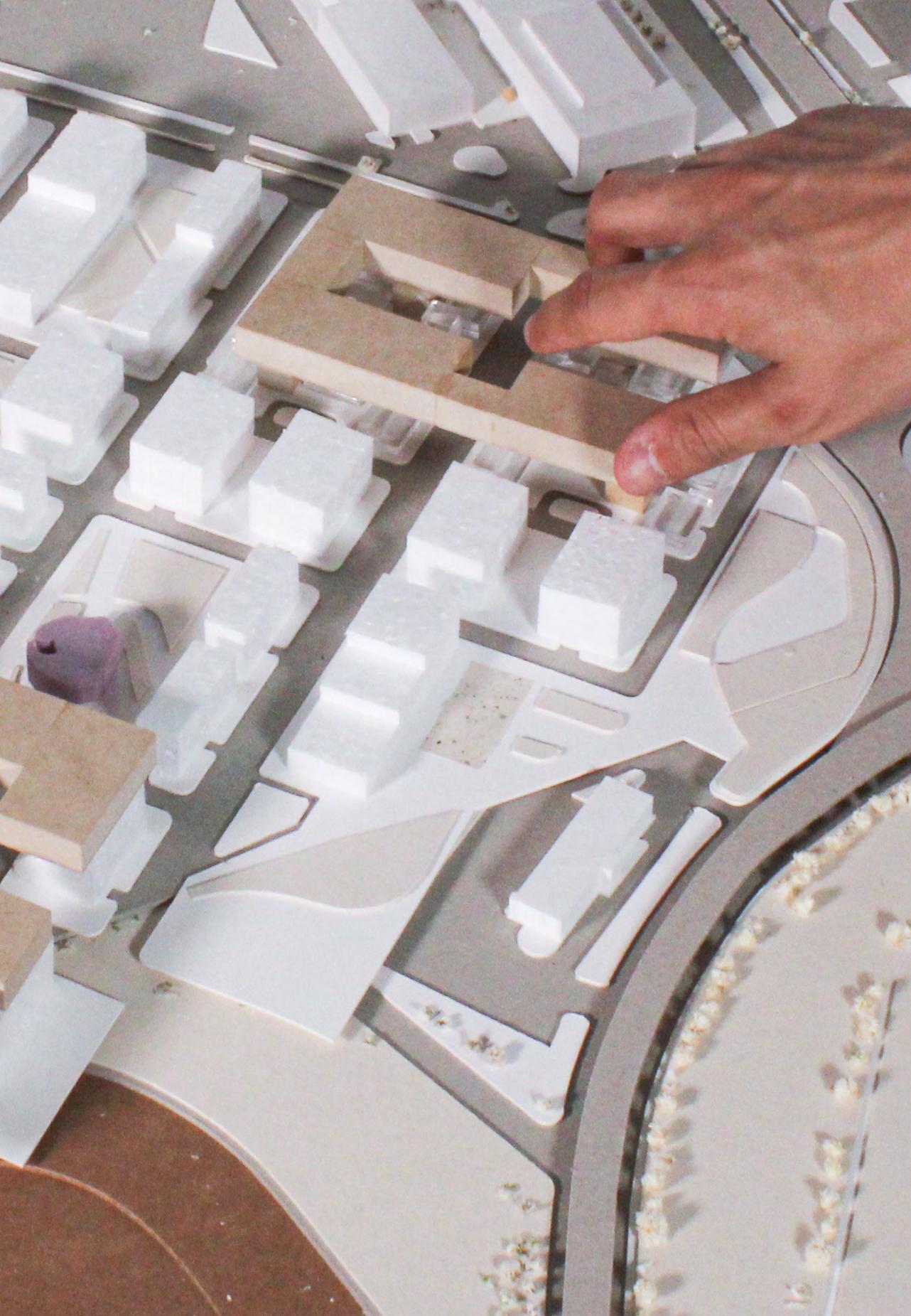

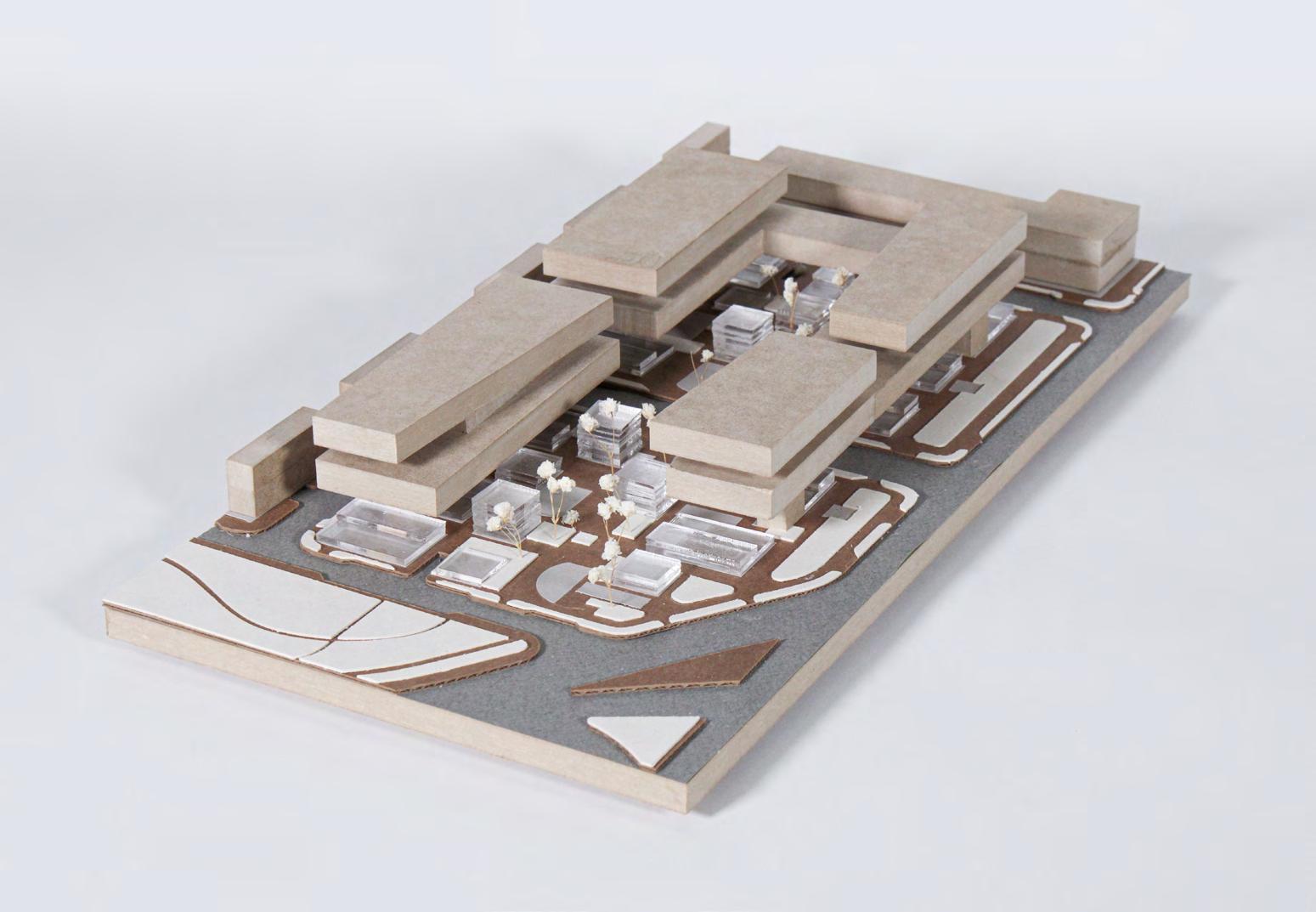

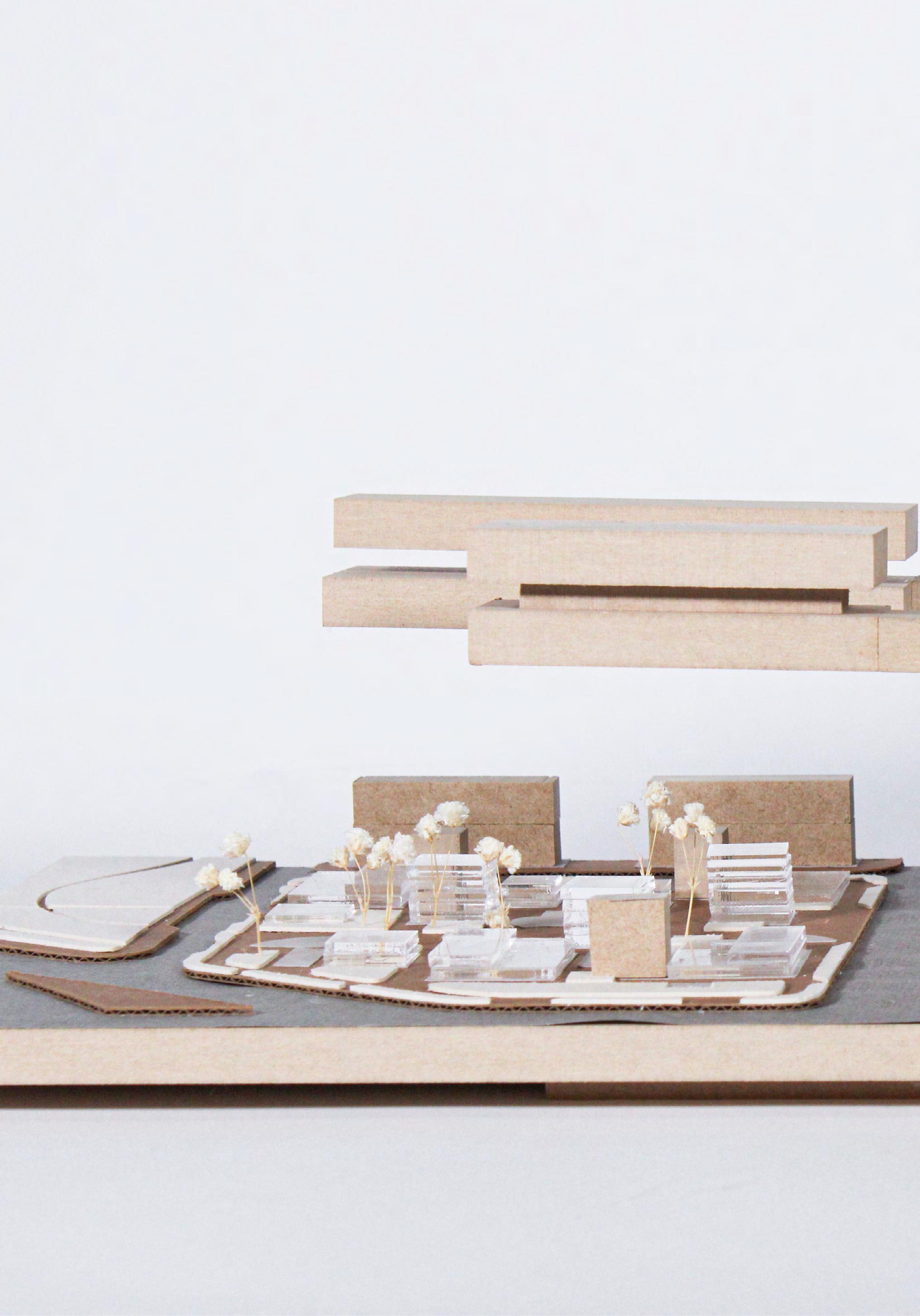

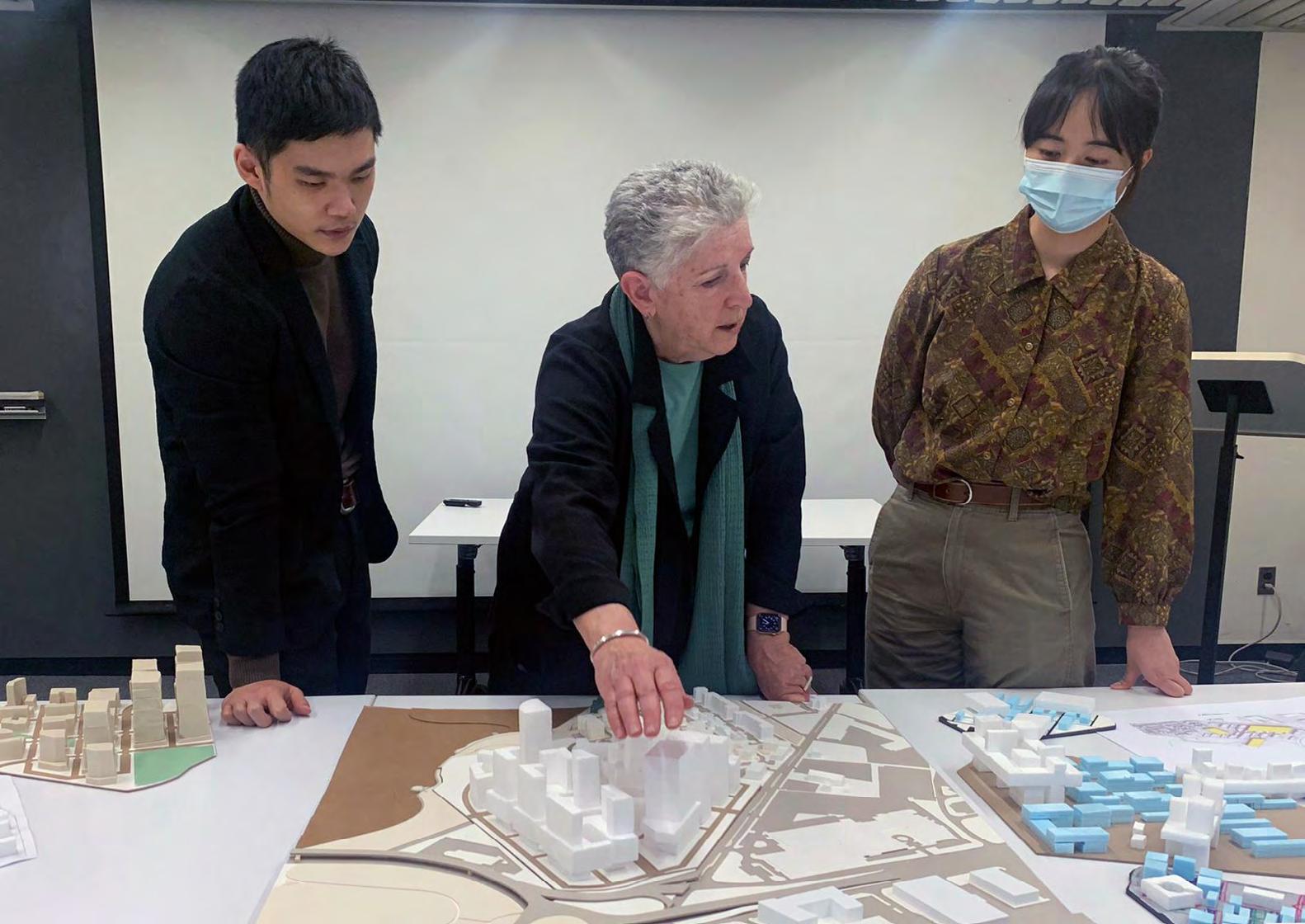

Exploration of the architectural/open space projects began with studies at 1:500 showing the project in its ensemble. Further studies at 1:200 were encouraged to explore principal interior spaces and building envelope and ground plane development. Physical models were the principal tools of study, amplified and supplemented by drawings, particularly experiential views. In developing site strategies, students were asked to explore various floor area ratios for the site, from as-of-right to proposed higher densities.

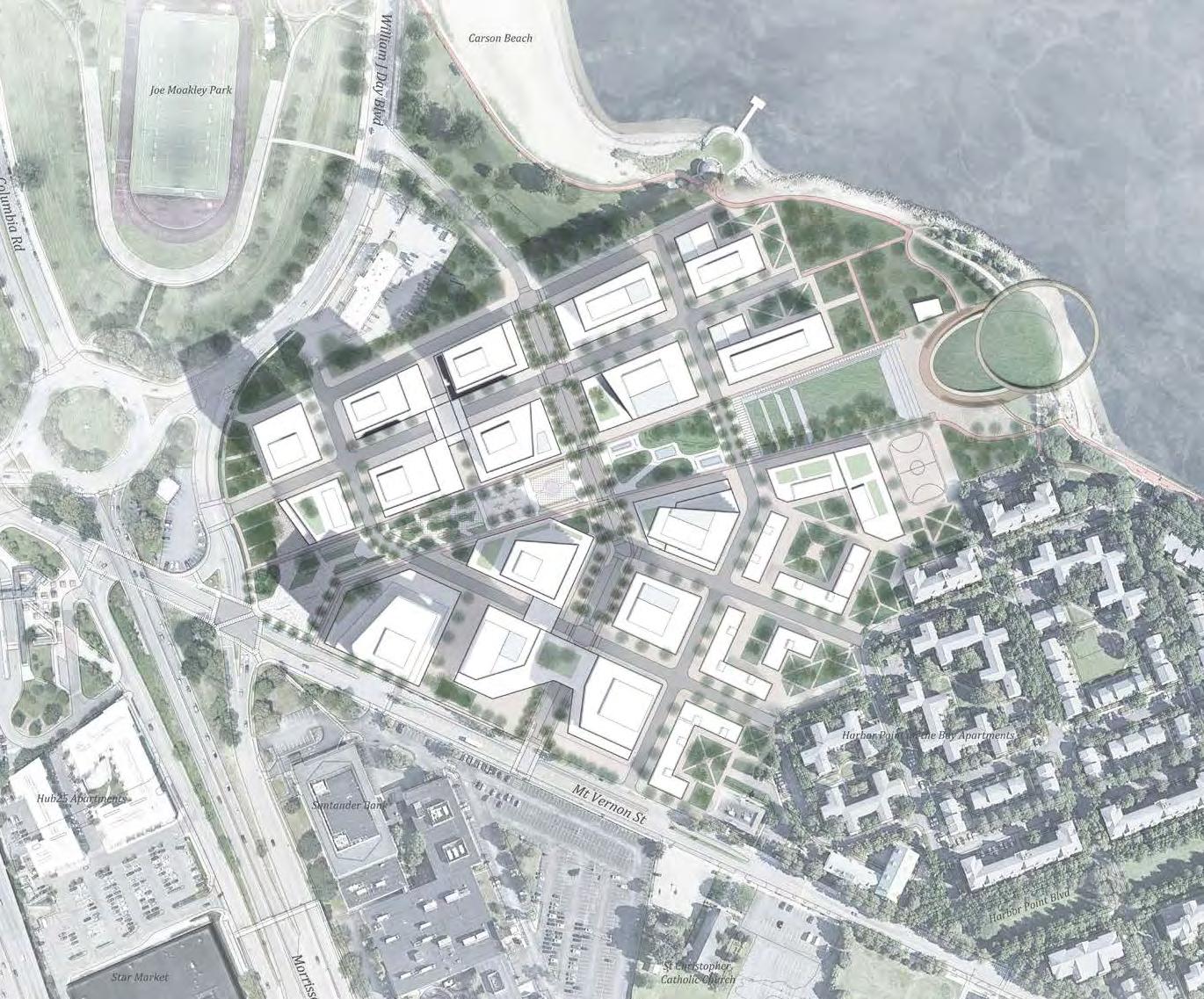

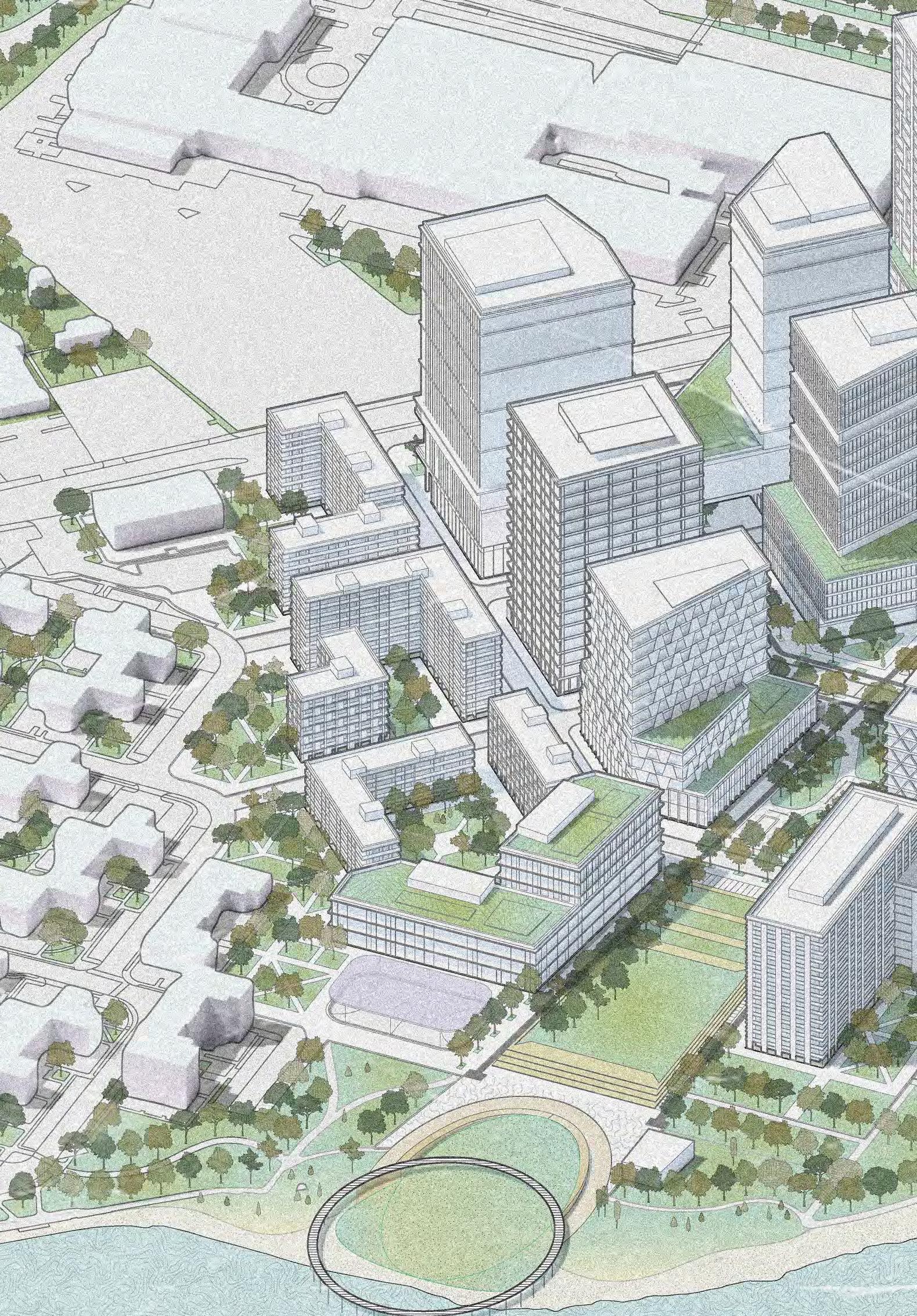

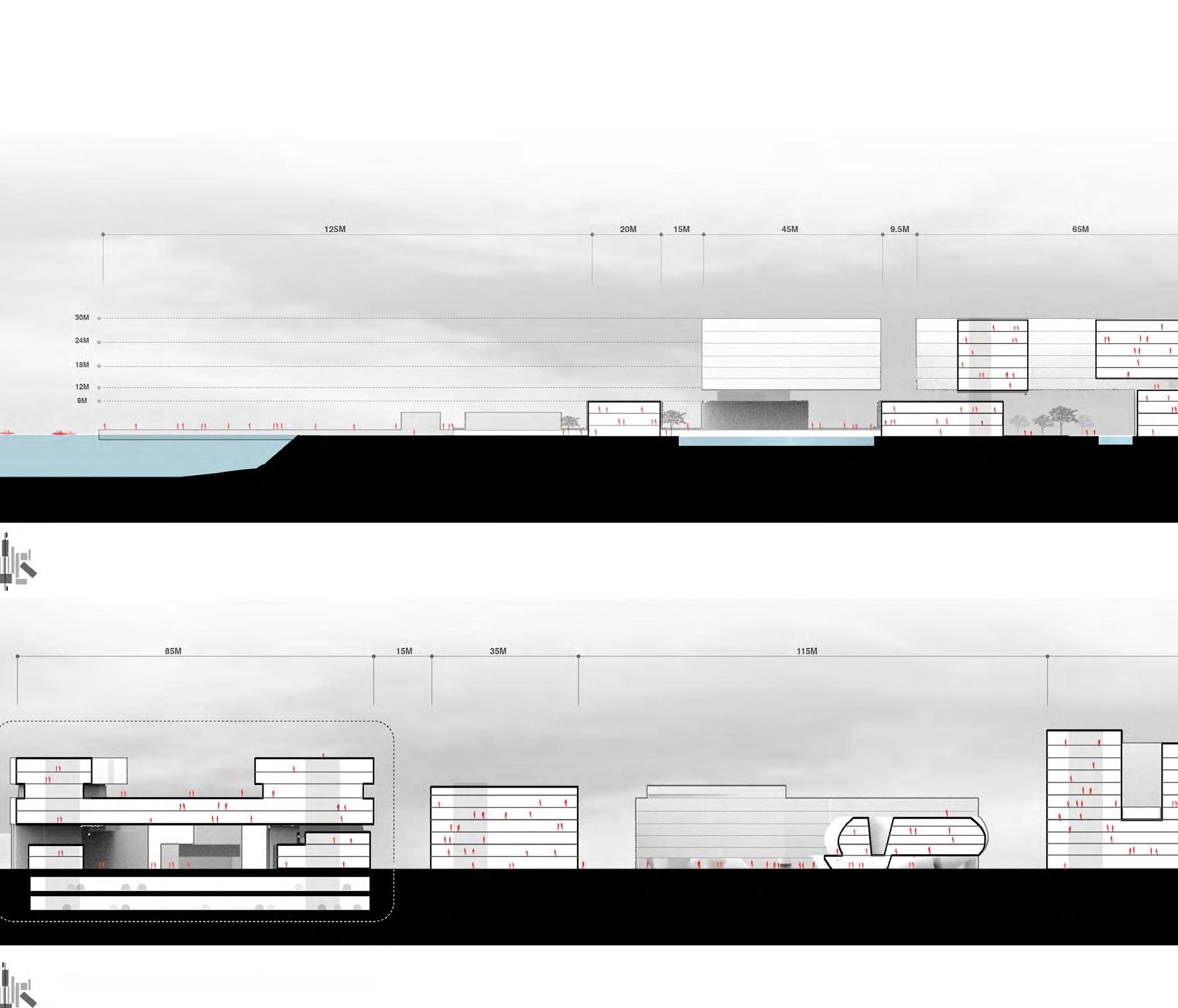

By establishing a new grid that merges existing grids on the site and generates new connections, Dorchester Innovation Commons (D.I.C.) is centered around the introduction of a central boulevard and greenway that connects the Dorchester neighborhood to the waterfront. The resultant block structure establishes a language of tall towers and shorter bars, stepping down from the street to the harbor, culminating in the “Bay Ring” functioning as a waterfront public space.

D.I.C. addresses density and includes climate resiliency measures responding to sea-level rise and flooding hazards by waterfront and ground plane earthwork designs. D.I.C. examines the innovation economies with a financially feasible development model that strategically transforms the underutilized industrial land into a vibrant neighborhood hub.

Top Right: Context Plan

D.I.C. is a mix-used development of office, R+D lab, housing, retail, academic, and community service spaces in a 30-acre land immediately adjacent to the J.F.K. red line station, where metro, commuter rail, bus, and bikeways make the development extraordinarily accessible.

Bottom Right: Plan D.I.C. provides over 800,000 SF of total ground floor open space, including a pedestrian-only mall and a street network accommodating bicyclists, vehicles, ground-floor retails, restaurants, and other uses for a vibrant destination.

Floor Area Ratio 3.72

Construction Phase 5

Construction Period (Years) 15

Educational Space (SF) 152,950

Community Space (SF) 190,865

Total Open Space (SF) >800,000

Keys at One Hotel (Units) 436

Diverse Residential (Units) 735

Dorchester Innovation Commons

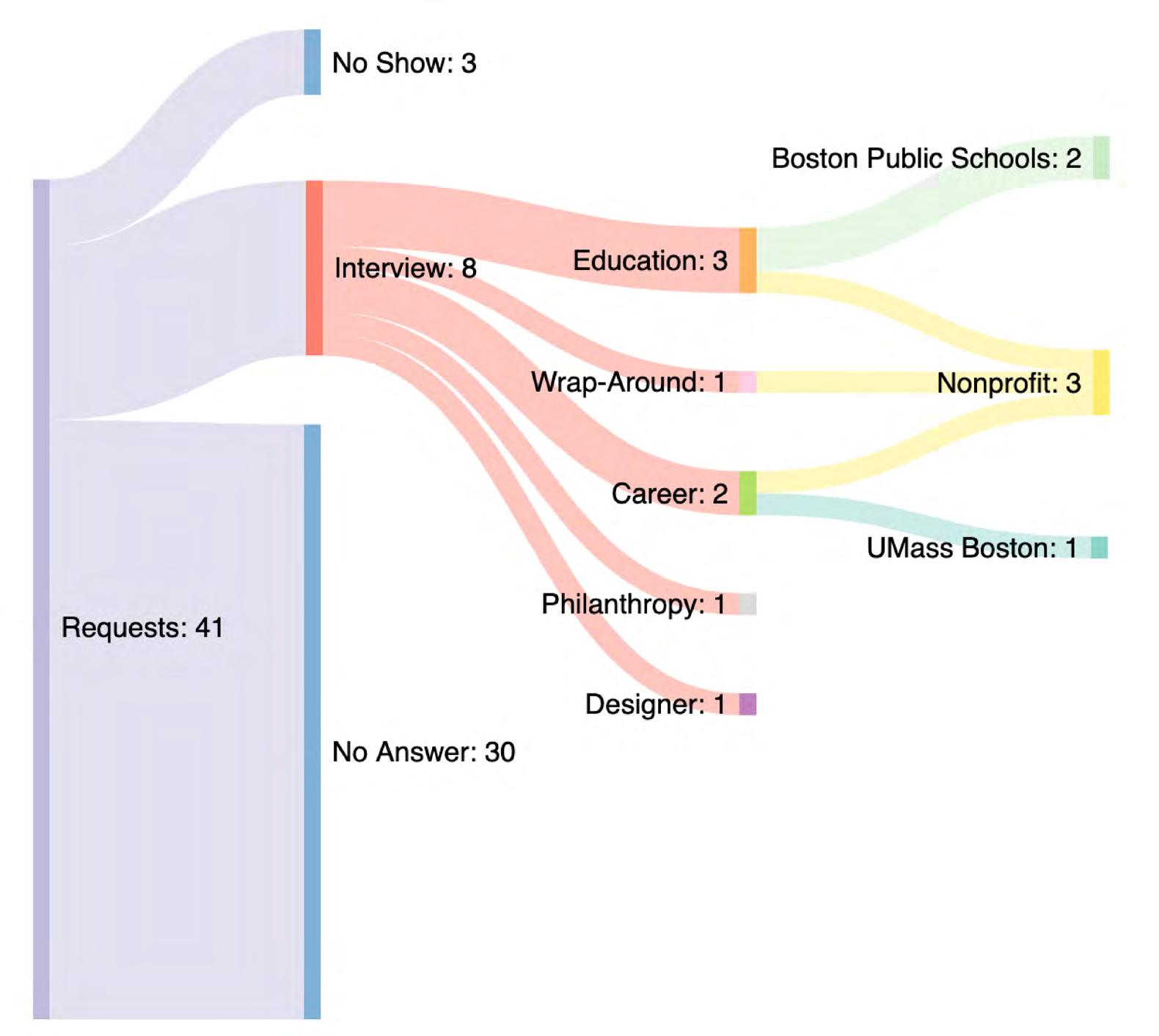

What resources do Boston’s youth and adults need in order to access pathways into the Innovation Economy?

What are the real challenges that Boston’s educators and service providers currently face?

How can we leverage an innovation district’s unique qualities to make it the optimal site for educational enrichment and career advancement?

“Kids love anywhere they can just congregate and hang out for hours. They were always going to the movie theater after school, but I don’t think they ever really watched any movies.”

Teacher, Boston Public Schools

“We need to provide mentorship to students and show them real life examples of what they want to achieve. Some of my students express big dreams for the future, but I don’t think they know what it takes to get there.”

Teacher, Boston Public Schools

“Boston’s education and job training ecosystem excels in that it has great relational strength. But at the same time, there’s a mismatch between supply and demand for the Innovation sector.”

Researcher, Boston Private Industry Council

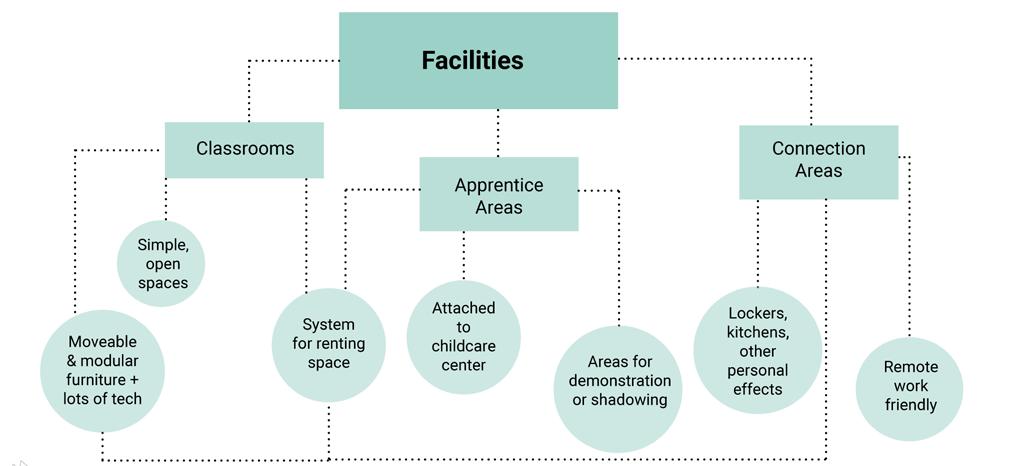

Participatory Innovation: Pathways to Prosperity for Bostonians

An Adult Learning and Career Training Center with Hands-On Apprenticeship

Participatory Innovation: Pathways to Prosperity for Bostonians

Youth (18 and under) Enrichment, Offering After-School and Summer Classes and Career Development

Greenway to the Bay sets up a new grid for the site that takes cues from the various existing grids, organized around a primary axis connecting Mt. Vernon Street with the harbor. The project creates two large public spaces as anchors to cap the new green boulevard, and places lower-rise housing blocks adjacent to the Harbor Point housing to the east, with taller commercial and R&D buildings with ground floor retail to the west and organized around the central spine. It is thus the landscape through a network of programmed public green spaces, that ultimately organizes the site and links architectural elements.

Participatory Innovation: Pathways to Prosperity for Bostonians

Participatory Innovation: Pathways to Prosperity for Bostonians

Urban Grid

Urban Form

Birdseye Looking North

Birdseye Looking South

The well-tempered grid attempts to construct a new spatial identity and experience of an innovation district through addressing the tran¬sition from industrial-age urbanism to information-age urbanism, probing for the decentralization of work in the city, and redressing the programmatic stratification through hybridization. By confronting the Columbia Point site morphologically and typologically, the project stands as a decentralized scheme.

The new continuous urban fabric is a residential one that is disrupted by three distinct micro-environments that are strategically placed to respond to their immediate adjacencies. First, is the district gateway, housing biotech, and pharmaceutical labs. Second, the learning commons extends the existing harbor point housing to create a shared communal institution. Finally, the eco-innovation hub retains the existing boardwalk from UMass to Moakley Park, providing an aquatic ecology institution that projects into the water.

Saad Boujane, Naksha Satish

The Well-Tempered Grid

Saad Boujane, Naksha Satish

The Well-Tempered Grid

The projects in the studio represent the collaborative, interdisciplinary efforts of urban design and planning, architecture, and landscape architecture students. The projects reflect diverse approaches with respect to density, building scale, and heights, architectural expression, and urban frameworks; each creating a dynamic innovation district that clusters R&D lab space, housing, retail, and community services to create a district that is equitable and well-connected to its surrounding neighborhoods and the city at large. While the projects propose a diversity of approaches, they suggest a consensus about certain critical elements. Moreover, the studio was among the first to return to in-person learning following the COVID-19 pandemic moving courses online for the 2020-2021 academic year. The opportunity to engage a close analysis of the physical site through in-person field work and to attend seminars with stakeholders and expert lectures was a critical aspect of the studio. Finally, the studio offered a unique opportunity for the GSD community and Harvard University to engage closely with and give back to its home city. The following key considerations were learned from the research and design work:

1 An “enterprise and innovation district” is a recent product of the market and not a well-established urban type. As such, clever programmatic integrations and the creation of good public spaces are critical to making them vibrant, well-connected places.

2 As such, the heights and configuration of buildings are less important; the projects demonstrate a range of medium to high densities are convincing, from 4-6 story to taller buildings.

3 The integration of program is critical, and how the anchor programs of an innovation district (lab spaces, retail, etc) integrate with housing and community service programs (Boys and Girls Club, community art and education, childcare facilities, etc) are the key to making innovation districts good neighbors to the city at large and avoid becoming gated economic communities. Programming to support community needs should include training centers, no-fee indoor activity spaces, family-oriented recreation and outdoor spaces, and inviting access to the waterfront.

4 Site strategies that are most convincing, then, conceive of the site as a critical link between the Dorchester neighborhood and the waterfront. As such, they treat the ground plane as an urban meeting grounds and connective tissue. The projects demonstrate that a coherent urban grid and its ability to weave together these entities, is therefore critical.

Principal and co-founder of Leers Weinzapfel Associates in Boston MA, Andrea Leers is an internationally recognized leader in urban, campus and civic design. A pioneer in mass timber design for academic settings, her practice is honored with over 100 international, national, and regional design awards, including the 2007 AIA National Firm Award. A monograph on the firm’s work “Made to Measure: the Work of Leers Weinzapfel Associates was published in 2011 by Princeton Architectural Press.

She is the former Director of the Master in Urban Design Program and Adjunct Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and has taught at Yale, University of Pennsylvania, University of Virginia, and the Tokyo Institute of Technology. She was Chaire des Amériques at the University of Paris, Sorbonne, Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome, and NEA Japan-US Friendship Commission Fellow in Tokyo. Her recent book “Welcoming the West; Japan’s Grand Resort Hotels” was published in 2017 by JOVIS Verlag Berlin.

Andrea is the current Chair of the Mayor’s Boston Civic Design Commission, and a member of the University of Washington Architectural Advisory Commission, and the Harvard University Design Advisory Pool. She holds a Bachelor of Arts in art history from Wellesley College, and a Masters of Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Fine Arts.

Anthony Averbeck is an urban and architectural designer, academic, author, and researcher who has taught at Harvard University, the University of Virginia, and Northeastern University. He has coordinated and taught several architecture and urban design studios, led seminars on architectural representation and theory, and has co-taught summer programs in early design education, including GSD Design Discovery and the UVA Summer Design Institute (SDI).

Averbeck has collaborated with leading design practices in Boston, New York, Minneapolis, and Charlottesville; including Somatic Collaborative, Arctic Design Group, Leers Weinzapfel Associates, and Bjarke Ingels Group. He holds a Master of Architecture in Urban Design, with Distinction, from the Harvard Graduate School of Design (2022), a Master of Architecture from the University of Virginia (2016), and a Bachelor of Science in Architecture, with High Distinction, from the University of Minnesota (2011).

Anthony is the recipient of numerous scholarships and grants for academic merit and research scholarship; including from the Dean’s Merit Scholarship, the Edelstein Family Foundation, the Stary Foundation, and the Center for Global Inquiry and Innovation. He is published in the Harvard Urban Review and LUNCH Journal, and is co-author of a forthcoming book titled “Collective Living and the Architectural Imaginary.”

Leveraging Boston’s Building Boom to Advance Equity

Instructor

Andrea Leers

Design Critic in Urban Planning and Design

Teaching Associate

Anthony Averbeck

Report Editors

Andrea Leers

Anthony Averbeck

Pinyang Chen

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah M. Whiting

Chair of the Department of Urban Planning and Design

Rahul Mehrotra

Copyright © 2022 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2022 by their authors.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

Harvard University

Graduate School of Design

48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu