Research Issue

personal and cultural renewal in the 21st century

Waldorf Education, Rhythms at Threefold A Library’s Timeless Conversation Steiner as Artist, American Destiny Humanity in Dying, in Prison, in Need

www.centerforanthroposophy.org

Celebrating Rudolf Steiner’s 150th Anniversary: 1861-2011

Renewal Courses

Week I: June 26–July 1 • Week II: July 3–8

Two weeks of five-day retreats bringing together Waldorf teachers and others for personal rejuvenation and social renewal through anthroposophical study and artistic immersion.

Karine Munk Finser, Coordinator

Week 1

Van James Drawing Course, Grades 1-12

Christof Wiechert Health-Bringing Curriculum

Georg Locher

Exploring Study of Man, Balance in Teaching, and Curriculum Painting

Douglas Sloan

Encountering Evil

Tobias Tuechelmann, MD Healing Traumatic Childhood Experiences

Leonore Russell & Carla Comey AWSNA Mentoring Course for Experienced Eurythmists

Elizabeth Auer Artistic Projects for Children Aged 7-12

Iris Sullivan Veilpainting

Marcy Schepker Needlefelting for Classroom and Community

Lorey Johnson & Kati Manning World Languages in Grades 6, 7, and 8

Juliane Weeks & Monica Amstutz Music in the Light of Anthroposophy

Week 2

Virginia Sease

Celebrating 150 Years of Rudolf Steiner

Jennifer Greene

Understanding Water

Aonghus Gordon & Master Craftsmen Education through Craft and Rhythm

Philip Thatcher

The Parzival Story

Janene Ping

Bee Man of Orn in Puppetry

Jamie York

Making Math Meaningful in Grades 6, 7, and 8

Leonore Russell & Torin Finser

Personal and Organizational Renewal

Georg Locher, Douglas Gerwin, & Hugh Renwick

Transformation of Self

Evenings include:

Music

Lectures

Eurythmy Performance

Artistic Café-Soirees

Slides of R. Steiner’s Blackboard Drawings

Waldorf High School Teacher Education Program

July 3–29, 2011

Douglas Gerwin, Director

Three-summers program of pedagogical courses, artistic workshops, and specialized subject seminars in

Arts/Art History with Patrick Stolfo

English with David Sloan

History with Meg Gorman

Life Sciences with Michael Holdrege

Mathematics with Jamie York

Physical Sciences with Michael D’Aleo

Pedagogical Eurythmy with Leonore Russell

Humanity’s Path of Evolution Leads Through Each of Us

Our first word this time must be, “Thank you!” for your warm reception of our first, special issue. Fred Amrine’s lead article on Rudolf Steiner was especially praised for clarity and forthrightness. For longtime admirers of Steiner and his work it demonstrated that his importance for human civilization can be well and clearly stated. The new layout by Seiko Semones was praised for its spacious and welcoming simplicity. Some concerns reached us about the stylization of the cover and inside portraits of Dr. Steiner, and they were not outwardly as reverent as customary. As David Adams once again reports inside, Steiner was and is a force in the arts and culture generally, and worked with contemporary impulses all his life. Our portrayals aimed to suggest the dramatic inner worlds into which this great explorer ventured again and again: environments he described, here and there, in such dramatic terms as “putting one’s head into an anthill.”

This second issue of being human focuses on research. The editor’s thoughts are presented inside; here we would like merely to point out one of anthroposophy’s staggering perspectives: that the evolution of humanity as a whole is proceeding now through the hearts, minds, and wills of each of us individually. In that sense, “being human”—when it is self-conscious and intentional—is the growing edge of what we, and the Earth with us, shall become. And “research,” which in traditional Western science would exclude the human element completely if possible, is central to how we attempt that personal development which becomes part of humanity’s development. In a culture flooded with trivialities, it is not easy to take in something this large and consequential. Just to think such a thought sets in motion changes...

The articles inside touch on several aspects of anthroposophical or spiritual-scientific research. Special note is made of the Research Institute for Waldorf Education, and of the continuing rebirth of research at the Threefold Educational Center. Two public conferences connected with sections of the School for Spiritual Science are described up front in line with the theme. Rudolf Steiner

Library Newsletter material begins with a very short but significant piece by Judith Soleil on the history and conceptual organization of the library itself. David Adams then reviews two large European exhibition catalogs devoted to Rudolf Steiner’s influence and role in modern art. And Walter Alexander reviews another very interesting historical juxtaposition by Kevin Dann.

General Secretary Torin Finser gives a report (p.34) of the annual general meeting of the worldwide Anthroposophical Society just held in April. Members of the Anthroposophical Society will find a supplement with the annual report of the worldwide society, along with the international study theme for the year.

In the Thresholds section we remember Lexie Ahrens and Hilde Maria Frey, two exemplary doers and builders of anthroposophical life in America. The News & Events section has much to preview and report on, but only a fraction of what is going on in this energized year of Rudolf Steiner’s 150th birthday, and short notices of new books and messages from our greatly appreciated advertisers complete this issue. Yes, it is shorter than the first issue, which was a special, celebratory double issue.

Our authors: Bill Day is development director for the Threefold Educational Center. Kevin Dann has taught history at the university level and is the author of several books, one of which is reviewed in this issue. Judith Soleil is librarian at the Rudolf Steiner Library in Ghent, NY. David Adams writes about and teaches art history, is a former Waldorf teacher, and is a member of the council of the Art Section of the School for Spiritual Science in North America. Walter Alexander writes about health, is contributing editor for Lilipoh, and is co-president of the New York branch of the Anthroposophical Society. Next issue we expect to include authors’ email addresses; for now write to them at editor@anthroposophy.org.

Online: Costs of printing limit our pages, but much more is being posted in the Articles section of our website, anthroposophy.org. With the next issue we will begin to list some of them here.

John BeckBeing human, briefly noted

Love in Action - Truus Geraets

This small, important book by healing eurythmist Truus Geraets and her soul mate Dawud (David Anglin) is a painful, truthful, intimately human look at the enormous and disastrous US correctional system. It gathers real symptoms for thoughtful students of societal failure, and it is a lifeline to those inside and out, an affirmation that “we are all on a path of development.” We received it shortly before a close friend was to be released on parole, after five “bids,” from the NY state prison system, and quickly sent it to him. Its authenticity moved and reassured him. How important that someone knows and cares to write about the terrible stress inflicted hourly on almost every inmate! And about the catch-22’s and prejudgments which fill life on parole with anxiety and frustration.

“To believe in the higher self of the other as much as of one’s own, isn’t that another expression of LOVE?” asks Truus in the Foreword. She found that belief unexpectedly with Dawud while giving eurythmy lessons in a Michigan prison over thirty years ago. We learn of her strength, Dawud’s unforseen capacities, and then how caring for someone in prison pulls at and expands one’s horizons. Marriage, release, divorce, new charges—all unfold against the background of Truus’ work across the USA and in Africa and Dawud’s struggle to endure the system. Love in Action is a tough handbook for how to hold onto hope inside, and to sustain another person with belief, from outside, in their true being. — Available online at www.trafford.com and other major book sites.

Most Excellent Dying - Nancy Jewel Poer

The Most Excellent Dying of Theodore Jack Heckelman is a new, award-winning film by Nancy Jewel Poer. It was a gift from big brother Jack to his sister, Nancy, who after many other important efforts over decades now works to help individuals and families “live into dying.” Finding himself faced with an aggressive cancer early in his eighties, Jack decides to give his dying to his community: family, friends, fellow social activists. He becomes in the process a real elder in the traditional sense: someone whose conscious, purposeful approach to birth into the next life becomes a sacred exercise of the capacity to love, for himself and all his people.

The contents of this film are almost too perfect; as fiction it might have been over-reaching. In fact it is all the most genuine home video, real folks speaking and singing not perfectly but from the heart, while Jack’s high ideals, spoken beautifully from a lifetime of social activism, are edged by the emotional strain of letting go and approaching the unknown. And along with sister Nancy there is Jack’s younger second wife Linda Bergh, who had already experienced and learned to work with the devastating death in a car accident of her daughter and a close friend. Through these and many other threads a web of destiny is revealed, which Nancy as filmmaker explores with great artistry. — Available at www.nancyjewelpoer.com, along with the book Living Into Dying

Anthroposophy Social Forum

Truus Geraets is also working with Ute Craemer, Aban Bana and Ben Cherry towards the realization of an Anthroposophical World Social Forum which would highlight the many social projects and initiatives which have arisen on anthroposophical foundations and the thousands of people in inhumane conditions touched by them, in medicine, education, agriculture or other fields. A first social forum was planned for April 2011, leading into the Asian-Pacific Conference in Hyderabad, to meet others who carry this initiative and learn from them. Truus Geraets will be celebrating her 80th birthday. (From Thomas Stöckli in Anthroposophy Worldwide.)

Waldorf WOW Day

For sixteen years European Waldorf schools have devoted a day each year to raising funds for educational projects in developing and emerging countries worldwide. Organizers hope for this to spread to the USA. In 2011 WOW (Waldorf One World) day is set for September 29th. To learn more visit www.wowday.eu (and click on the little British flag), email na.wowday@gmail.com or contact Truus Geraets (949-646-6392) or Leslie Loy (503-819-3399).

Note

Author’s reply to Keith Francis’ review of Metamorphosis – Evolution in Action

Darwin’s historical achievement lies in grounding, or incarnating, the idea of evolution. The fact that aspects of his work need to be corrected hardly diminishes the greatness of this achievement. Nor is it diminished by the circumstance that he drew his concept of the survival of the fittest from the social thought of his time and applied it to non-human nature. The concept was formulated by Thomas Malthus in his writings on the upheaval and conflict arising from the industrial revolution in England. Darwin had already developed the idea of evolution but had not yet been able to resolve the question of natural selection, i.e.: What are the factors that determine which species of plants or animals survive while others become extinct?

Darwin was referring to Malthus’ sociological treatise An Essay on the Principle of Population when he wrote of his own book, The Origin of Species : “This is the doctrine of Malthus applied to the plant and animal kingdoms.” Elsewhere Darwin is yet more explicit: “In 1838 I was reading the book by Thomas Robert Malthus for pleasure. I was well prepared to accept the struggle of existence, and the book convinced me that, in this struggle, well adapted species would survive and the less well adapted would be destroyed… Now I had a theory I could work with!” (Charles Darwin, Life and Letters, London, 1887)

Today we know that the factors at work in evolution are not the competitive struggle for existence and mutual exclusion but rather on the contrary differentiated associations within nature as a whole. The science of ecology – unknown at Darwin’s time – has since identified the actual ordering structures in living nature: symbioses and synusiae such as those arising between plants (the “producers”) and other organisms (the “consumers”) who nourish themselves from the vegetable substances plants have produced. At their death, the physical substance of all organisms is reintroduced into the universal life cycle by the “destroyers” – fungi and microbes. Thus one group of organisms provides the basis for the existence of others. When carnivores are depicted as the enemies of their prey, the inadequacy of such a concept becomes evident in light of the fact that, though they decimate them, they never do so to the extent that they destroy them. Their

prey remain the basis of their own existence. In the last analysis, both the carnivores and their prey are parts, or “organs,” of one super-ordinate organism. Neither could exist without the other! Further examples could be cited ad infinitum.

In this broader ecological context, the principle of the struggle for existence loses its validity. It turns out to be an anthropomorphic concept that has no place in natural science and, worse still, falsifies the relationships that actually exist in nature.

Seen in the context of Darwin’s central discovery –the idea of evolution – Malthus’ theory can now be seen as an aberration of the times that appeared so convincing because of its “human” connotations.

Much remains to be done in developing a deeper ecological understanding that will provide the basis for a non-exploitative, nurturing relationship to nature. This also needs to become an essential aspect of how life sciences are taught in schools. In the future, the further development and elaboration of the idea of evolution will reflect the evolution of human culture itself.

To sum up: Darwin’s significance – his extraordinary significance – lies in the fact that he introduced the idea of evolution into human consciousness. In the light of this great achievement, the erroneous aspect of his theoretical explanation is of negligible importance especially as it only illustrates the fact that the idea of evolution is itself capable of evolving.

Andreas Suchantke(Editor’s note: the review to which this letter responds, printed in Evolving News’ Research Issue 2010, is available at anthroposophy.org under Articles.)

Symeon the New Theologian

Janet Clement of Richmond, Maine, sent “thanks for the quote from Symeon the New Theologian,” in the report of the 2010 conference of the North American Council for Anthroposophic Curative Education and Social Therapy. Jaimen McMillan quoted these thousand-year-old lines which anticipate Rudolf Steiner’s picture of “the Christ” as a cosmic being offering to all a renewal of life forces. Symeon’s words:

And let yourself receive the one who is opening to you so deeply.

For if we genuinely love Him, we wake up inside Christ’s body where all our body, all over every most hidden part of it, is realized in joy as Him,

and He makes us utterly real, and everything that is hurt, everything that seems to us dark, harsh, shameful, maimed, ugly, irreparably damaged, is in Him transformed and recognized as whole, as lovely, and radiant in His light we awaken as the Beloved in every last part of our body.

Anthroposophy as Biographies

L. Ahrens of Chestnut Ridge, New York, sent two typed pages of excerpts from Anthroposophy in the 20th Century: A Cultural Impulse in Biographic Portraits , edited by Bodo von Plato, an 1100 page volume in German from 2003 with short portraits of almost a thousand anthroposophists. August Bier, a famous Berlin surgeon born the same year as Steiner, followed biodynamics but never joined the society. Louis Locher, the youngest person at the Christmas Foundation Conference, later led the section for mathematics and astronomy and died in a fall in the Swiss Alps. Of those deceased, the average lifespan was 75, with the 25 eurythmists averaging 82 years. American Olin Wannamaker lectured to members in Los Angeles when he was 97.

Ten Commandments of Black Love

Editor’s note: “black” in the following context refers not to an ethnicity but to an experiential condition of life.

I’m the singer/songwriter for the Los Angeles band Black Love—we make music about loss, specifically the loss experienced when a relationship breaks up. Inspiration and hope are often in short supply when that happens, and so I’ve written these Ten Commandments of Black Love.

Thou shalt not talk thyself out of thine own power.

Thou shalt love thine own voice.

Thou shalt not give the game away.

Thou shalt follow thine own star.

Thou shalt not fear loneliness.

Thou shalt embrace awareness in all its forms.

Thou shalt not lose perspective.

Thou shalt continue to care.

Thou shalt not reject the good will of others.

Thou shalt never forget.

With these commandments, I’m telling my audience not to give in to depression or anger, not to give in to feelings of lack, to be strong and proud for having lived through something inescapably traumatic that will

ultimately make them better individual adult human beings. Seeing as now there’s “The Ten Commandments of the Mafia,” “Financial Happiness,” and even “Driving,” I thought it might be beneficial to return to the purity of the current. I appreciate how rare it is for rock musicians to actively seek out other spiritual points of view—even the anthroposophical view—but I did want to reach out to you in some small way and bridge the gap with these ideas. We may not see eye-to-eye on all things, but I’ve always wanted to create art that strives towards both the living of a good life and transcendence—something I know we can all contemplate and appreciate. Thanks for your time and consideration, keep up the good work.

David CotnerPunk & Porn, Ahriman & Lucifer

The following exchange of letters is directed toward our sister publication, the Journal for Anthroposophy, which does not have space to accept letters. At the suggestion of the editor of the Journal’s “Classics” series, it is printed here. In Rudolf Steiner’s depiction of spiritual forces challenging and opposing (and potentially aiding) human evolution, Ahriman and Lucifer form a dynamic polarity.

The article by Michael Howard on beauty in the Michaelmas 2008 issue of the Classics from the Journal for Anthroposophy argues that pornography is luciferic and the “punk look” is ahrimanic. I appreciate the attempt in the article to describe these things, but I think it errs. While listening to Brahms the day after reading the article I was suddenly moved to speak: I feel strongly this statement is backwards, or at least oversimplifying things, and understanding the truth of the matter would help the anthroposophic cause in general. I am not a well-versed anthroposophist, and I don’t know these terms as well as the experts, but I do know something about punk and something about porn.

The punk look is from a luciferic impulse of selfabnegation and is feeling-based, an unfunded expression of that grief which the wearer feels the culture has not acknowledged. Pornography is ahrimanic—it is very sustainable in a worldly sense, since you will never lose financially at opening a brothel, but there is no attempt to leave worldliness in porn. There is no ideology aimed at, no feeling that is being expressed, but rather the sup-

pression of feeling for the sake of the dollar. Women who actually enjoy their sexuality and their beauty display it in a wholly different way, a way that includes romance; those who chose to be objects for pornography numb out all romance in themselves for pragmatism and efficiency.

The “beauty” in pornography is destructive to the other, and in punk it is sacrificing of the self. At the same time, of course, each thing has elements of the other, too. But the implication that punk is unfeeling, detached, and worldly is really a mistake. Those who make talismans that are closest to the Other World in Africa in particular make them as ugly as possible—they are terrifying to look at for the human in us, but the spirit recognizes them as coming from our true home. The comparison is of apples and oranges—punk is a deliberate approach to life, whereas porn makes no attempt to be anything. A better comparison would be to look at the beauty of the factory and the beauty of the pornography printed in it.

Anonymous Unschooler

Reply from Michael Howard: Thanks very much for your email. Even though you are voicing a critique on an aspect of my essay, nevertheless, I am gratified to know it has engaged your interest sufficient to motivate you to write.

I certainly don’t have any issue with the implication that human experience is complex and that often luciferic and ahrimanic qualities are interwoven. I certainly see the point that pornography has an ahrimanic side, particularly in creating it. I was probably thinking more of the voluptuous, expansive and compelling attraction that pornography can evoke.

By the way, I use the word pornography not only in the literal sense but with the meaning James Joyce uses in his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man , to describe all that makes us unfree through compelling attraction—which seems to me a good characterization of what Steiner means by luciferic. That which makes us unfree through compelling loathing or revulsion, Joyce calls the didactic—which seems to me to point in the direction of the ahrimanic.

So it was in this sense that I must have latched onto the “punk look” that strikes me--rightly or not--as intentionally anti-beauty, that can evoke revulsion and loathing. It was in that sense that I used it as an example of the ahrimanic. But in reading your descriptions, I realize speaking about punk was a bad choice given that I do not

know it from the inside as you clearly seem to.

Given the spiritual complexity of human nature, your comments support the view that, in any given situation, we have reason to look for the gesture and activity of both the ahrimanic and luciferic spirits. That assumes we have a growing feel for the qualitative attributes of the luciferic, as compared to the attributes of the ahrimanic. As a starting point, I understand the luciferic is that which makes us unfree through being over-expansive, warm, lightfilled and lifted out, while the ahrimanic is contracted, cold, dark and heavy. The luciferic is full of self, proud and over-confident, so that one sees only oneself and not the other. It is over-idealistic, living in fantasy that disdains reality. The ahrimanic is for me more complicated, because on the one hand it appears as compelling fear and anxiety, and self-abnegation. But on the other hand the ahrimanic manifests as cold, unfeeling logic that acts with mechanistic precision, and most especially, is driven by power to control nature and other human beings.

From what you say, I see how some aspects of the ahrimanic do not apply to the punk culture. The only place that does not ring true to me is your equating the self-abnegation of the punk attitude with the luciferic.

As much as I think we are meant to learn to work with these terms luciferic and ahrimanic, similar to the way it is essential for a painter to discern warm colors from cool colors, I certainly do so cautiously, in the assumption that I may misapply them in a given situation, or that I may be over-simplifying a more complex reality.

So thanks for your stimulating reflections, and I hope you likewise may be motivated to continue refining your capacity to discern the activity of these spiritual forces in every domain of life.

Michael HowardAnonymous Unschooler replies:

I really appreciate that all of you took the time to write back to my email. I guess I do want add two things:

I think the article has helped me see something about myself, that I have tended to lean toward the ahrimanic much more than my perception of myself told me I did, and that that has repeatedly cost me and others. [And] having a dialogue about it helped me in a way that I can’t necessarily explain, certainly not in the time I have right now, but it is generally more helpful to me to have a dialogue with an author than simply to read.

Anonymous Unschooler

Research, Science, & the Human Being

by the Editorthe h uman Being

The first “basic” or foundational book by Rudolf Steiner was A Philosophy of Freedom . Already this title invites us into a small research problem, since Steiner indicated that English “freedom” did not adequately translate the German “Freiheit”; its suffix, “-heit,” points to an active capacity, while “-dom” indicated a defining condition. The missing English cognate would have been “freehood”—like “womanhood,” “manhood,” “brotherhood,” “sisterhood.” The suffix “-dom” aligns more with “kingdom” or “fiefdom” or “serfdom.” So the title is sometimes rendered “a philosophy of spiritual activity”—but that loses the “free” to which we Americans feel so connected. Such questions of the human inner life are central to anthroposophy.

With this issue we take up for the second year the question of anthroposophical research: what is it, how is it faring, where might we lend a hand. Rudolf Steiner’s first foundational book is important to this research in two ways. First, it is a record of his own fundamental research path. Page by page it reflects Steiner’s exploration of his own consciousness. He hoped for the book to be taken up by deeply committed and self-aware seekers: human beings looking for the way forward in human evolution. Americans are misled, again, by the title, since our impulsive culture does not see in the word “philosophy” the forward-driving enterprise which it was for Steiner. Interestingly it was, according to Steiner, some American anarchists in Europe who first “got” what he was saying. (A true anarchism is not mere lawlessness, but a search for how human beings can be both social and free.)

The second importance of A Philosophy of Freedom for research is that it shows us something essential about anthroposophy, as Rudolf Steiner developed it. The word “anthroposophy” had been around, but had never established itself clearly. Meanwhile, the similarly old word “anthropology” was being given its modern sense: a comparative study of human beings and cultures in different

places, with emphasis on the exotic and “primitive,” and across different times. This was, as G.K. Chesterton put it later, a science not so much of human beings as of anthropoids. In the dominant culture, that body of concerns and that view of the human being which would be a true inquiry into our own human place and significance in the cosmos was dismembered and parceled out among a dozen or more emerging sciences, with no central unifier.

So anthropology fit itself into a modest place in a broad and materialistic scientific enterprise, being neither more comprehensive nor more central to “science,” to human understandings, than zoology or botany. It could not be otherwise under materialism, when the specifically human elements that differentiate us from animals and plants and minerals are located in consciousness, mind, spirit. Moreover, since the early 1600s “hard” science sought to pull the human being back to the sidelines of research, a cool and detached observer. “The experimenter stands apart from the experiment!” That was the hopeful cry of those trying to objectify science and free it from petty human emotions and personal ambitions.

It was a further problem in Steiner’s youth that this “objective” science had come to certain limits. In 1872, when he was eleven, the German physiologist Emil du Bois-Reymond gave a famous lecture On the Limits of Natural Science (Über die Grenzen des Naturerkennens) and followed in 1880 with a speech to the Berlin Academy of Sciences where he presented seven “world riddles,” three of them “transcendent” or insoluble. Essentially these “boundaries” remain today in the questions, “What is matter?” and “What is consciousness?” They defy science’s hope to make all of reality knowable, thinkable.

Resea R ch s cience & the h uman Being

With his scientific training and natural clairvoyant experiences from childhood, Rudolf Steiner set out to find a way through these limits, and A Philosophy of Freedom is his research report and guidebook. What he found was that the dead-ends of modern natural science can be overcome only by placing a view of the human being back in the central, fundamental position of all research. To solve the riddles of the world, we must solve the riddles of the human being, as he states plainly in the 1918 preface to the revised edition.

Turning from the beginning to the end of his life’s work, at the end of 1923 Rudolf Steiner established a School for Spiritual Science at the Goetheanum in Switzerland. In this school and in the Anthroposophical Society which supports it, ancient, esoteric knowledge flows together with the fruits of modern natural and human sciences on the basis of an evolutionary strengthening of the human being’s soul forces. Rather than exclude the human being, include it—and take personal responsibility for that choice! So after three centuries of pushing the essentially human to the side, it is a science of mind and spirit —a Geisteswissenschaft, where “Geist” means both mind and spirit (but usually rendered in anthroposophical writings just as “spiritual science”)—which assumes a new, central role in overcoming the limits to knowledge.

A Call for Research

In 1991 Henry Barnes, one of the preeminent figures in the first century of anthroposophy in America, recalled and repeated Rudolf Steiner’s 1923 appeal for this new research to be developed as rapidly as possible.

It was the next to the last morning of the Christmas Conference for the Founding of the General Anthroposophical Society, December 31, 1923. The two morning talks dealt with aspects of scientific inquiry. The first, by Rudolf Maier, concerned “The Connection of Magnetism with Light,” and the second, by Dr. Lily Kolisko, dealt with the “Physical Proof of the Working of Microorganisms.”

Rudolf Steiner introduced Dr. Kolisko’s talk with the following observations:

“If it should become possible for anthroposophy to give to the different branches of science impulses of method which lead to certain research results, then one of the main obstacles to spiritual research existing in the world will have

been removed. That is why it is so important for work of the right kind to be undertaken in the proper anthroposophical sense.”

After her talk he continued:

“These experiments are, from an anthroposophical point of view, details leading to a totality which is needed by science today more urgently than can be said. Yet if we continue to work as we have been doing at present in our research institute, then perhaps in fifty, or maybe seventy-five years we shall come to the result that we need, which is that innumerable details go to make up a whole. This whole will then have a bearing not only on the life of knowledge but also on the whole of practical life as well.

“People have no idea today how deeply all these things can affect practical daily life in such realms as the production of what human beings need in order to live or the development of methods of healing and so on. Now you might say that the progress of mankind has always gone forward at a slow pace and that there is not likely to be any difference in this field. However, with civilization in its present brittle and easily destructible state, it could very well happen that in fifty or seventy-five years’ time the chance will have been missed for achieving what so urgently needs to be achieved...”

Rudolf Steiner concluded by saying what it would mean if it were possible for anthroposophical research to achieve in five or ten years what, he foresaw, would take fifty to seventy-five years at the speed at which work was then going forward. And he ended by saying:

“I am convinced that if it were possible for us to create the necessary equipment and the necessary institutes and to have the necessary colleagues, as many as possible to work out of this spirit, then we could succeed in achieving in five or ten years what will now take us fifty or seventy-five. The only thing we would need for this work would be 50 or 75 million francs, then we would probably be able to do the work in a tenth of the time.”

Henry Barnes followed this recollection with a forceful appeal, sixty-eight years later (and just after the fall of the Soviet empire in East Europe), for this research work to be taken up more energetically in the USA.

Two questions immediately arise: What is spiritual-scientific research? and: How

can it be furthered?

In response to the first question, we should bear in mind Rudolf Steiner’s observation quoted above that it is the “’impulses of method leading to research results that are so badly needed.” Once the method of inquiry has been opened up, it then becomes possible for colleagues in the field, who are of open mind and of good will, to share in the detailed investigations. As we know, the methods of spiritual-scientific research have been described by Rudolf Steiner in many places and, especially, in such fundamental works on the path of knowledge as Knowledge of Higher Worlds and its Attainment, and Occult Science, Chapter V.

In these descriptions we find three stages: in the first, we take the results of spiritual-scientific investigation and, as students, make them our own through the activity of clear and selfless thinking, which we have prepared to become the first instrument for higher knowledge. These living thoughts are ours because we have experienced them. In the second stage, we enter the realm of life, and, through meditative exercise, we acquire the capacity to perceive the living world as it begins to reveal itself in the language of imagination. At this stage of experience, the living images we perceive are the projections of supersensible reality, mirrored within our soul, not yet the immediate reality of spiritual experience itself. It is only when the third stage is reached and we have the inner strength of activity to erase the pictured world from consciousness that we are able to enter that stillness of being, deeper even than outer silence, in which the spiritual world itself begins to speak and sound within our soul. Beyond this experience of inspiration, as Rudolf Steiner describes it, there lies, as we know, the realm of experience in which being knows being in the immediate cognitive experience of intuition.

As one becomes familiar with the anthroposophical path of inner schooling, one discovers that what distinguishes spiritual-scientific research from the investigations of natural science is that, in the former, it is the researcher himself who is both instrument and knower, whereas in natural science the data is supplied by sense perception, extended through the use of technical instruments and theoretical models, which are then analyzed by the intellect, itself also a “given.” Responsibility, therefore, rests with the spiritual-scientific investigator to a degree unknown in natural scientific research. With these brief reflections on the nature of the method of anthroposophical research in mind, let us turn to the second question: how can it be furthered?

In a certain sense, everyone who is working with anthro -

posophical insights, whether as an individual on the path of self-knowledge, or as a colleague in some one of the practical enterprises which have their origins in anthroposophy, is already engaged in spiritual-scientific research! However, we are rarely conscious of this fact. We are constantly learning, comparing the results of previous investigations with the next new insights we have gained, and through this activity also expanding our capacities as a “knower,” as one who is engaged in research! Clearly, however, Rudolf Steiner had something else in mind when he spoke to the members gathered in Dornach nearly sixty-eight [now eighty-eight] years ago. He was pointing to the urgent need to free qualified individuals from their daily tasks so that they could devote themselves on a full-time basis to the work of research. He was thinking of institutes in which teams of individuals would work together, approaching the same questions from different sides, with the needed equipment at their disposal. [Emphasis added.]

Where We Stand in North America

As reported in our first research issue (Evolving News, 2010, #2, p.17), a fund for anthroposophical research has been created in Henry’s name. This helpful stimulus joins other significant developments since 1991, some of them reflected on the following pages:

First, a Collegium in North America of the School for Spiritual Science has grown to maturity and is carrying consciousness and fostering collaboration for all the sections of the school in our continental context.

Second, independent research institutes have been established: the Water Research Institute of Blue Hill, Maine (1991), the Research Institute for Waldorf Education (1996), and the Nature Institute, in Ghent, New York (1998). More recently, the Threefold Educational Center has resumed a research role. For many years Ehrenfried Pfeiffer had a research laboratory at Threefold for his work in biodynamics.

Third, practical research is done by anthroposophical pharmacies, doctors, therapists, biodynamic groups, RSF Social Finance, and small initiatives; by faculty at Rudolf Steiner College, training institutes, and Waldorf schools, in Camphill, the Rudolf Steiner Fellowship Community, and other intentional communities.

Fourth, there are notable efforts by individuals (Dennis Klocek, Frank Chester, and Richard Tarnas, for example), and by artists whose research flows into and is expressed by their creative work.

Resea R ch s cience & the h uman Being

And finally, it is all documented and disseminated by SteinerBooks, small publishers, and libraries.

Anthroposophy fosters a culture of research based in personal responsibility. As Henry Barnes noted in 1991, it begins with the individual student, of whatever age, who is “raising” and enlarging her consciousness. And this new approach to research flows together from disparate fields—natural science, social science, humanities, arts, esoteric streams, spirituality—around one unifying element: the strengthening of human consciousness by meditation and exact imagination, inspiration, intuition.

Research Institute for Waldorf Education

In direct response to Henry Barnes’ appeal there emerged a research initiative for Waldorf education in North America. Though devoted to one field of initiative, its value is very broad. Education, after all, is central to all human becoming.

Education is also the focus of tremendous social pressures. Financially it is a big business. Being sponsored in the USA largely by local, state, and federal governments, it is also an area of accountability for politicians and public servants. And tens of millions of parents and grandparents take education very seriously, because it enhances or limits the lifetime possibilities of their children and grandchildren. The children, too, take an interest!

Waldorf education is immediately appealing to many parents, especially those with young children. Even so, the beautiful concepts underlying Waldorf need serious research to support them.

Douglas Gerwin and David Mitchell are co-directors of the Research Institute for Waldorf Education, which receives “support and guidance from the Pedagogical Section of the School of Spiritual Science and financial support through the Association of Waldorf Schools of North America (AWSNA), the Midwest Shared Gifting Group and the Waldorf Schools Fund and The Waldorf Curriculum Fund.” It has supported research on “essential contemporary educational issues such as attention-related disorders, trends in adolescent development and innovations in the high school curriculum, learning expectations and assessment, computers in education, the role of art in education and new ways to identify and address different learning styles.”

The institute’s work takes shape in a twice-yearly Research Bulletin, colloquia, conferences, extensive free resources at waldorfresearchinstitute.org and the On-

line Waldorf Library at waldorflibrary.org, and further notice in Renewal magazine. It has supported the hugely challenging work of Waldorf teachers and given the movement and its schools a significant grounding and credibility. Asked on short notice for a few recent samples of the Institute’s work, we received a wonderfully diverse collection. Pride of place must go to “Standing Out without Standing Alone: Profile of Waldorf School Graduates.” This extensive survey of North American graduates gives a very definite sense of what Waldorf has to offer.

For teachers, there is “Creating a Sense of Wonder in Chemistry,” an excerpt from David Mitchell’s book. There’s a review by Dorit Winter of The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes, the noted biographer of Romanticism, “academically impeccable” but also “making the life of the subject experiential for the reader.” From a different angle comes “Soul Hygiene and Longevity for Teachers.” Waldorf teaching expects much of teachers, and the article gives a series of concrete self-development and hygienic processes to support them. For educators and parents there is “Social-Emotional Education and Waldorf Education,” bringing home the broadly if intermittently recognized truth that “Children’s social-emotional development is as important as their intellectual and physical development.” And another essential and very “hot” topic: “Assessment without High-Stakes Testing: Protecting Childhood and the Purpose of School.” Finally there are “reflections on a recent visit” to Russia where a hopeful first growth of Waldorf education is now learning to live with challenges from government, church, and economic and social dysfunction.

In the chaos of Europe, the millions for investment that Rudolf Steiner once hoped for did not materialize. Human-centered spiritual research—creative and deeply responsible—has still, tenaciously, taken root in North America. May we all participate and help it to flourish!

Living Research at Threefold Educational Center

by Bill DayAt the 1924 Christmas Foundation Conference, Rudolf Steiner placed spiritual scientific research at the center of the work and mission of anthroposophy. In 1926, Threefold Farm in Spring Valley, New York, was founded as a living laboratory for spiritual science in social threefolding, biodynamic farming, and the arts. Threefold’s

mission was codified in 1965, when the Threefold Educational Foundation was chartered by the State of New York Education Department “to establish, conduct, operate and maintain conferences, programs of research and adult education in all fields of human endeavor emphasizing the principles and methods enunciated by Rudolf Steiner.”

We recognize that research is not a luxury, it is a necessity—life itself depends on it. However, research, like any living thing, requires a convergence of essential elements in appropriate amounts. These elements include: qualified researchers carrying worthy questions; time and space in which to do research, and means for researchers to live on; and a social and physical setting that is supportive of the researchers’ work. In short, what is urgently needed is for qualified researchers to be paired with appropriate institutional, social and financial support.

Over the past eighteen months, Threefold Educational Center has consciously acted on its task as an anthroposophical institution, which is to create and foster

the conditions necessary for spiritual scientific research to take place. A series of conferences hosted by Threefold have brought together interested parties from all over North America and Europe, in part to investigate and discuss the nature and meaning of such research in the past and going forward. A community of researchers and a constellation of questions have been identified. The institution continues to develop its physical facilities to create appropriate spaces for working, meeting, exhibiting and performing, a process that evolves as new needs and opportunities arise.

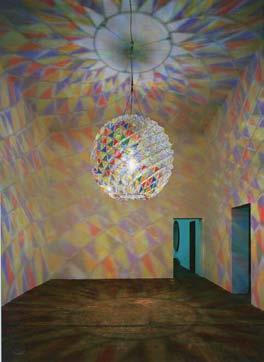

A major step in this effort was the creation in 2010 of the Threefold Researcher in Residence program. Our first Researcher in Residence, artist and geometrician Frank Chester, worked with a team of eleven research fellows at Threefold from September 19 to October 30. Frank and his co-workers constructed a truly collaborative learning community: a common language (alchemical transformation), common content (forms arising from the platonic solids), and a common research protocol (the lawful working of the four elements through geometry).

The work of this team of researchers culminated in an exhibition at Threefold Auditorium, “Art as Research and Scientific Inquiry as a Creative Act.” The exhibition included sequences of geometric forms built in paper, clay, cardboard, Plexiglas, wood and various metals; photographs; spinning forms; models of interior planes; a journal examining the relationship of music to form and health; forms in edges dipped in soap solution; an alchemical explanation of the chemistry behind that soap solution; sculptures weaving the elements with human development through birth, death and resurrection; and a “geomation” short film made up of almost 2,000 still pictures. All the pieces on display were works in process,

artifacts of each researcher’s line of inquiry that also offered a window onto the group process as a whole.

The exhibit’s opening on November 5 coincided with a symposium, co-sponsored by Threefold and the Collegium of the North American School of Spiritual Science, entitled “How Do I Research My Questions?” Presentations by physician Gerald Karnow, educator John Barnes, scientist Henrike Holdrege and eurythmist Dorothea Mier set the tone for a weekend of explorations into the nature and meaning of spiritual scientific research, starting at the level of each individual’s personal questions: How do individuals identify and begin to work on our life questions? Can pursuing this intimate, personal process help us develop a methodology for spiritual scientific research? How can we connect our personal quests with our responsibility to all of humanity, and to the cosmos?

Threefold’s Researcher in Residence program will continue in 2011 with a two-week fellowship led by Frank Chester and Dorothea Mier on the theme “Into the Center of Our Heart.” As in 2010, a dozen applicants will be

selected to work and study with Frank and Dorothea at Threefold beginning in late September. The fellowship will culminate in a symposium that will provide rich and unusual opportunities to experience some of the results of the residency and further explore the themes in a social setting.

Visit www.threefold.org/research for more information about the Threefold Researcher in Residence program, including details on how to participate in the 2011 program. To get updates about the 2011 program sent to you, join the Threefold email list and check the box indicating your interest in the program.

Rhythms of Spiritual Scientific Research at Threefold

by Kevin DannThe title page of The Book of Lambspring (1599) – an alchemical text by Nicolas Barnaud, a member of Rudolf II’s Prague alchemical circle – bears an illustration of a venerable grey-bearded man holding a staff in his right hand, while his left hand rests upon a threefold furnace. The prefatory text below vows to unveil “the one substance/In which all the rest is hidden,” and encourages the reader, through “Coction, time, and patience,” to doggedly pursue the alchemical philosopher’s art, but then pulls back to warn of the derision that he will receive if he shows his hard-won knowledge to the outside world. “Therefore be modest and secret,” the author counsels. A series of polar emblems follows: two Fish swimming opposite to each other; a battle between a Dragon and a Knight; the meeting of a Stag and a Unicorn in a forest clearing; a Lion and Lioness walking together; a fight between a Wolf and a Dog. The text accompanying each emblem gives specific spiritual instruction, but again, there are warnings: “Hold your tongue about it”; “Let those who receive the gift enjoy it in silence.”1

In a cave-like side chamber at the opening reception for the research exhibition “Art as Research and

Scientific Inquiry as a Creative Act,” researcher-artist fellows Dan Wall and Simeon Amstutz gesture at the figures on their chalkboard diorama rendering of The Book of Lambspring. “The very first page of the book says to keep the knowledge secret,” they exclaim in puzzled disbelief, as they conduct an enthusiastic show-and-tell of their own process of discovery in transforming a 16thcentury alchemical text into a stop-motion film. In the main room, nine other researchers point and poke and spin geometrical models; hold up sculptures for close inspection; gesticulate before complex handmade charts, eagerly sharing their discoveries with the uninitiated audience. What would Nicolas Barnaud say to all this

public proclamation of the Alchemical Art?

Since its founding by Ralph Courtney and Charlotte Parker in 1926, members of the Threefold Farm (now Threefold Educational Center) community have struggled mightily to penetrate and communicate the secrets of Nature and History. When, in 1933, the 33-year-old Ehrenfried Pfeiffer delivered his first American lecture at the first Anthroposophical Summer School Conference, he chose as his topic “Making Visible the FormativeForces in Nature.” His teacher, mentor, and friend Rudolf Steiner advised Pfeiffer on his course of college study, and, for the last five years of his life, closely collaborated with him on his research. In a large circus tent set up in the oak grove beyond the Threefold Farm garden and barns, Pfeiffer began his 1933 Summer Conference address by condemning contemporary natural science’s relentless endeavor to turn Natura into a corpse, and society’s reckless use of the subearthly forces of nature – electricity, magnetism, and gravity.

Back in 1920, Pfeiffer (then a young engineering student) had asked Rudolf Steiner if there might be some way of using the constructive, synthetic forces as the foundation of a new altruistic technics that would have within itself the impulse of life rather than death. In response, Steiner set his student to the task of demonstrating the etheric forces in visible form, by developing a substance that would react with the Bildekräfte (etheric formative-forces) in plants and human blood. Though the odds against success were incalculable, Pfeiffer – with the help of Erika Sabarth, who discovered copper chloride as the proper reagent – made the formative forces visible through the process of sensitive crystallization. He attributed this success to their having followed Rudolf Steiner’s advice to make the laboratory a place where the elemental beings of nature would feel comfortable, through a spiritual atmosphere of prayer and meditation.

A meditative state was also required to interpret the crystallization images, which to the untrained eye of the flesh appeared as little more than crystalline Rorschach blots. Pfeiffer distinguished subtle differences in the crystallizations, but when he reported his results to Rudolf Steiner, Steiner interpreted them as indicating that the time was not yet right for humanity to make use of the etheric forces; that time would come about only when the appropriate social conditions had been established in at least a few regions on earth. 2 Until then, no experiments toward an etheric technology should be conducted. Already by 1933, when he addressed the very group of

anthroposophists who had pioneered American efforts in founding social threefolding in New York City and then at Threefold Farm, Pfeiffer doubted that he would see the advent of the necessary conditions in his own lifetime, and felt sure that he would go to his grave keeping secret what little knowledge he had gained about the role of the etheric forces on existence in the sense-perceptible world. This was a decade before the most deadly sub-earthly force was discovered, with the splitting of the atom; in his biweekly lectures beginning in 1946 (Pfeiffer came to live and work at Threefold Farm in 1944), Pfeiffer repeatedly warned of the dangers of atomic radiation fallout, not so much for the immediate future, but for long-term Earth evolution. 3

As Rosicrucian initiates who were working far into the future in their spiritual scientific researches, both Rudolf Steiner and Ehrenfried Pfeiffer constantly found themselves quite alone, without sufficient financial support or a circle of colleagues capable of taking up and extending their initiatives. In a single lecture in 1952, Pfeiffer touched on numerous researches indicated by Rudolf Steiner: working with absolute zero temperatures to realize “warmth energy”; the study of plant ashes vs. mineralized ashes, in relationship to a study of the etheric light emitted by the eye; “peptonization,” the creation of remedies by experimenting with day and night rhythms (Ehrenfried Pfeiffer said that he believed 100 Ph.D. theses could be written on this!); and superimposing ultraviolet upon infrared light. In this same talk, Pfeiffer returned to the subject of the “Strader Machine” or “Keely Motor,” and once again spoke of the secrecy surrounding more recent efforts to develop a technology based in the etheric. 4 Three and a half centuries after The Book of Lambspring author cautioned about making esoteric knowledge public, this principle still held, not because of the potential for public derision, but because of the absence of the necessary social crucible into which this knowledge might be received.

The arc of Ehrenfried Pfeiffer’s life ended in frustration and disappointment, his work cut short largely for reasons beyond his control. When one looks upon the artifacts – the elegant mahogany- and glass-cased Fisher Scientific lab scales; fading photographs of plant experiments; didactic charts on soil physiology – from Pfeiffer’s laboratory, it is possible to feel wistful that this prodigious research project ended incomplete. Unlike the alchemists of old, the modern spiritual researcher can’t work in isolation, because his research can only rise and flourish in

the context of a social “soil” that is capable of receiving it. But even though Ehrenfried Pfeiffer had to curtail his work during his lifetime, in a sense it has been carried forward ever since by the ongoing efforts of the Threefold Community (individuals and the institution as a whole) to realize Ralph Courtney’s ideal of a “Threefold Commonwealth” that would be fully engaged with the deep mystery of American destiny. True, the manifestations of this work are not always outwardly visible, and progress may not be immediately perceptible, but the eager acceptance of the very exoteric work on display at “Art as Research and Scientific Inquiry as a Creative Act” showed Threefold at its best, as an eager incubator of spiritual investigation.

In the last emblem in The Book of Lambspring, a Father and Son sit on either side of “the Ancient Master”: “They produce untold, precious fruit/They perish never more,/And laugh at death.” New researchers and new impulses of research continue to arise, take form, and give way to succeeding generations, and the visions of the

standard-bearers of the past achieve renewed life in the hands of their successors.

1 Nicolas Barnaud’s text was originally published in Latin in 1599 in a collection of alchemical texts known as Quadriga aurifera . Arthur Edward Waite included the text as The Book of Lambspring in volume 1 of The Hermetic Museum, Restored and Enlarged (James Elliot and Company: London, 1893).

2 Using the crystallization method, Pfeiffer developed the ability to diagnose the nature and location of inflammations, infections, even cancer. Alla Selawry, Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, A Pioneer in Spiritual Research and Practice: A Contribution to His Biography (Mercury Press: Spring Valley, NY, 1992), p. 52.

3 See Pfeiffer, Notes and Lectures, Volume I, pp. 68, 85, 127, and in Volume II, his November 20, 1961 letter regarding atomic radiation.

4 Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, “Consciousness and Research Attitudes,” in Volume II of Notes and Lectures.

The Agriculture Course

An Intensive Midwinter Study of the Origins and Future of Biodynamics at the Pfeiffer Center by Bill Day

For the 2011 midwinter intensive study at the Pfeiffer Center of Rudolf Steiner’s 1924 agriculture lectures, the subject was the horn preparations, 500 and 501. As in past years, this weekend gathering featured challenging talks, a eurythmy performance, and convivial meals. New this year were small-group sessions that elicited questions and observations about the horn preps. The talking and sitting was leavened with group artistic activities with Deborah Lothrop (charcoal drawing) and Natasha Moss (eurythmy), prep making (grinding silica for 501), and hands-on experiments with water.

The two horn preps are alike (and unique) in that they are made by burying a substance in cow horns. In nearly every other

respect, they are not only different from each other, they are polar opposites. The cow dung that becomes 500 is dark, while the ground silica of 501 embodies light; 500 is buried in fall and spends the winter underground, while 501 is buried in spring and dug up in the fall; 500 is typically sprayed in the afternoon, with large drops directed at the soil more than the plants, while 501 is sprayed in the early morning, in a fine mist directed to the plants more than the soil. In their similarities and their differences, 500 and 501 remind us of siblings, tightly bound together yet emphatically distinctive, one from the other.

In talks that opened and closed the weekend, Pfeiffer Center Director Mac

500 and 501 remind us of siblings, tightly bound together yet emphatically distinctive...

Mead drew a line connecting the earliest stages of Earth evolution to our time. As depicted in Occult Science, the Earth’s evolution is measured in cycles of expansion and contraction, warmth and coolness, light and dark, order and chaos. These cycles manifest today in the rhythms of nature. Human beings are highly emancipated from the rhythms of nature, and the horn preps, if understood and used in the right way, give us an opportunity to bring those rhythms into our service. Mac suggested that we start by understanding the differences between metamorphosis (a movement from one state to that state’s polar opposite) and enhancement (a process of unfolding), two phenomena that exist throughout nature and also throughout the preps.

Malcolm Gardner’s talks on “The Logic of Horn Manure” and “The Logic of Horn Silica” were an attempt to “recover the rationale” underlying Rudolf Steiner’s indications. On their face, the preps do seem bizarre, but Rudolf Steiner did not arrive at them through trial and error, or by guessing, but through a rational penetration of the workings of nature. The rational aspect is not readily apparent because of the discursive nature of Steiner’s lectures, but Malcolm’s talks were on one level a clinic on how to tease out the logic underlying Steiner’s indications. That logic in turn suggests a path toward the “real science” that will emerge when science at last takes hold of unquantifiable forces. Yes, the elements such as carbon, nitrogen and oxygen are at work in nature’s household, but “for Steiner it’s not about the substances, it’s about the forces.” It is through diligent study of the forces at work that we can learn what it is the substances want to do—what processes of metamorphosis and enhancement they seek, for example, when they take up and throw off other substances, or change from solid to liquid to gas.

Forms and forces work hand in glove to make up the world around us. Where Malcolm took us deeply into the realm of forces, Steffen Schneider led us to consider the cow horn, a natural form that Rudolf Steiner put at the heart of the horn preps. What exactly are cow horns, and why do cows have them? What can we learn about horns by studying their form with an open mind, heart and will? How is a horn different from an antler, and how is the cow different from an elk or a deer? What does the form of the horn (which constantly changes over the life of the cow) tell us about its hidden functions as organs and sheaths— its role as an organ of perception, and its role in the cow’s metabolic life? Steffen’s personal explorations of these questions showed how much there is to ponder and learn

from even the most mundane objects in nature.

Stirring is central to making and using 500 and 501, but how often do we think about the properties and behavior of water? Jennifer Greene’s workshop on the subject included illuminating hands-on experiments as well as demonstrations that vividly illustrated how water creates sheaths in motion, generating an environment of almost unimaginable complexity every time we stir preps.

Mac Mead opened the weekend with this startling observation: “None of us has scratched the surface of what the preps are all about.” That may not be what we want to hear from our teacher, or even think about ourselves, but the level of humility it expressed created a mood entirely suitable for one’s own ideas and understanding of the horn preps to undergo metamorphosis and enhancement.

Next year’s midwinter weekend intensive at the Pfeiffer Center is scheduled for January 13-16, 2012. Mark your calendar, and watch www.pfeiffercenter.org for news and registration information in the fall.

Redeeming the Realm of Rights

A public conference sponsored by the Social Sciences Section

Along with financial and environmental crises, we are facing a crisis in democracy and human relations. Most notably, financial and corporate interests take priority over the rights of the people, resulting in human and environmental exploitation and international strife. This is not simply the result of defective outer arrangements, but is equally a failure of human beings to develop capacities needed for a true democracy and a healthy social life. Our institutions and social forms are a reflection of thoughts and feelings that people carry within them. Therefore, meaningful change requires not only transformation of the outer structures and arrangements but also an inner transformation of the people who are active within them, including developing enhanced listening and speaking and a greater interest in others.

The social threefolding ideas of Rudolf Steiner will provide a framework for this conference to explore our political heritage, some of the most pressing political is-

sues of our times, and the outer forms and inner capacities that we will need in the future to redeem the realm of rights. Along with presentations we will employ artistic exercises and focused and free form conversations to gain insights and develop new capacities.

Some of the confirmed topics we will consider are the social pathology of income inequities, rights in an intentional community, money as a right, school choice as a civil right, the right of access to land, transcending political parties, and rights as an earthly task. The confirmed list of presenters, conversation leaders, and artists at the time of writing include Peter Buckbee, Michelle Bourassa, Steve Burman, Jennifer Daler, Alice Groh, Trauger Groh, Sarah Hearn, Michael Howard, Seth Jordan, Gary Lamb, John MacManus, John Miller, Luigi Morelli, Patrice Maynard, Ulrich Roesch, Penelope Roberts, John Root, Jr., Channa Seidenberg, Christopher Schaefer, Denis Schneider, and Douglas Sloan.

Organizations collaborating to host this conference include the Berkshire Taconic Branch of the Anthroposophical Society, Center for Social Research at Hawthorne Valley, Think OutWord, and Banjo Mountain Café.

To make this conference affordable to as many people as possible the fee is on a sliding scale from $100 to $300. Complete conference information is available at www.rightsconference.org or by contacting Gary Lamb at garylamb@taconic.net or 518-672-7500, ext. 223.

Intrinsic Nature of Water

The Water Research Institute of Blue Hill is pleased to announce a conference, “Steps Towards Discovering the Intrinsic Nature of Water,” led by Jennifer Greene, Director of the Water Research Institute of Blue Hill, with Wolfram Schwenk and David Auerbach. This conference will begin Sunday evening, July 31st and end Friday, August 5th at 5pm. (On Saturday, the 6th is the wellknown Eggemoggin Reach Regatta, a true water event!)

Jennifer Greene is an educator and has led acclaimed water workshops nationally and internationally. Until his recent retirement, Wolfram Schwenk was the water biologist and senior scientist at the Institute of Flow Sciences in Herrischried, Germany. This Institute was founded by Theodor Schwenk, his father, author of Sensitive Chaos,

which Jacques Cousteau called the first phenomenological treatise on water. David Auerbach, PhD, worked many years at the Max-Planck Institute of Flow Sciences, in Göttingen, Germany.

Amidst the beauty of Maine’s Blue Hill Bay and Acadia National Park with its waterfalls, boiling springs and beach, this hands-on, experiential conference will consist of water phenomena, artistic activities, conversation and field trips, offering participants an opportunity to experience how movement, form and rhythm in water flow becomes the “language of its fluid nature”. We will endeavor to reach the kind of “fluid thinking” that is needed to become conscious of water as an element for life, its role in the natural world, and how it can teach us to understand ourselves as knowers and participants in the classroom, in nature, and in the world around us.

This workshop stands at the crossroads of the present debate around the nature of water. Native peoples the world over hold water to have sacred value as an element of life—all life without regard to rank. The modern world views water as a commodity to be moved and used to serve the greatest need of the consumer, very often to the detriment of nature and humanity. How we “see” water dictates how we manage it. It is hoped that by taking up the journey of allowing water to teach us, our attempts to understand “the language of water’s intrinsic nature” may help us to contribute to this dialogue.

This conference is for naturalists, educators, scientists, and anyone who has a passion for deepening their participation in the natural world around them. It is dedicated to the memory of Marjorie Spock, who lived many years on the Maine coast and was a deep friend of the Institute of Flow Sciences and the Water Research Institute.

For a full program contact Jennifer Greene at jgreene@waterresearch.org or call 415-254-9567.

Natural Science Section Meeting

The section’s annual meeting will take place at The Water Research Institute of Blue Hill (WRI), in Blue Hill, Maine, in order to take advantage of Wolfram Schwenk’s visit for the WRI conference. The NNS meeting, for members of the First Class only, will begin Thursday evening, July 28th and go to midday, Sunday the 31st, followed by the week-long water conference described above. David Auerbach and Wolfram Schwenk will be present for both meeting and conference. For more information, please contact the Section Council members: Jennifer

Greene at jgreene@waterresearch.org or 415-254-9567; Barry Lia at barrylia@comcast.net or 206-522-1937; or John Barnes at adonis@fairpoint.net or 518-325-1113.

Metamorphosis & Resurrection

Beginning in 2009, members of the Literary Arts and Humanities Section in North America have given special attention to the theme Metamorphosis and Resurrection as reflected in the Literary Arts and Humanities. Members have already discovered that this is a theme that can be productively engaged in a great many ways. For example, in Montréal Denis Schneider and Michel Bourassa bring creative writing activities that nurture processes of metamorphosis and resurrection in biography work, counseling, and special social events for the wider community; one of their initiatives is the “Peace Group”, which works co-creatively to portray and respond to current events.

Section members also are active in developing and presenting programs on a wide variety of topics for members and friends of the Anthroposophical Society here and abroad; often these projects are undertaken together with members of other sections of the School for Spiritual Science, such as the sections for the visual and performing arts. Many members serve the Anthroposophical Society and the world as translators, editors, creative writers, historians, and students of literature and language. Much of their activity results in written contributions to mainstream publications, to anthroposophical books and periodicals, and to the Section’s own newsletter.

Research as a Timeless Conversation

A Short History of the Rudolf Steiner Library

by Judith SoleilMuch has man learnt. Many of the heavenly ones has he named, since we have become a conversation and have been able to hear from one another.

—Hölderlin

There has been an anthroposophical lending library in the United States nearly as long as there have been anthroposophists. Pioneering member Caia Greene of the St. Mark’s Group created a lending library in New York around 1910 and “mailed books to interested persons all over the country and as far away as Honolulu….” In 1974, Fred Paddock began creating the library as we know it today.

Fred suggested that a true anthroposophical library, with philosophical works at its core, should also reflect anthroposophy’s calling to bring spiritual insights into various fields of activity: education, agriculture, medicine, the arts and sciences, philosophy, religion, and so on. His vision for the library was informed by a sense that the Anthroposophical Society’s future lies in “growing together with the world.”

Hipolito, Placentia, CAThe section’s work in North America is guided by its collegium: Fred Dennehy (fdennehy@wilentz.com), Bruce Donehower (bdonehower@yahoo.com), Jane Hipolito (janehipolito@earthlink.net), Douglas Miller (millerdoug@comcast.net), Marguerite Miller (margueritemiller@comcast.net), and Denis Schneider (dschneider@sympatico.ca). Any of them will gladly supply further information about the Literary Arts and Humanities Section and its activities. — Jane

More online: The text of Henry Barnes 1991 appeal, and an article by Michael Howard about the work of sections in the Anthroposophical Society, are posted at anthroposophy.org under Articles.

So, as well as a complete collection of books and lectures by Rudolf Steiner in English and German, the library would also aim to collect all translated and original English-language works by other anthroposophical authors and a good selection of original anthroposophical works in German. The library would also carefully select some of the best non-anthroposophical books in areas where anthroposophists are strongly active, including those by thinkers that Steiner himself had studied and spoken

about, such as Meister Eckhart and Jakob Boehme, and works by contemporary thinkers that Steiner would likely be reading were he alive today: for example, Richard Tarnas, Emmanuel Lévinas, Albert Borgmann, and Martha Nussbaum.

The library’s move from cramped quarters in Manhattan to Harlemville, New York, in 1982 allowed room for significant growth, and Fred Paddock enthusiastically began filling out the collection. He recognized that one of the library’s important tasks was to encourage and support anthroposophical initiatives such as Waldorf education and biodynamic agriculture. Fred sought materials to support teachers’ intensive preparation for main lessons: for example, collections of fairy tales, Bible stories, and Greek, Norse, and other myths; resources on ancient, medieval, Renaissance, and modern history; and background materials on the Grail legends. There was also demand for books in the sciences: botany, zoology, and physics; and books on arithmetic and more advanced mathematics.

As the library expanded, Fred recognized the emergence of an organizing structure that reflected the relationships among the different subject areas. He characterized these relationships as a living entity that asserted itself:

When you apply the concept of life, of livingness, to texts, what you are really referring to is conversation. I began to see that within the different sections, a conversation was going on… in the philosophy section… Descartes was carrying on a conversation with Scholasticism (and ultimately, with Thomas Aquinas). Aquinas was carrying on a conversation with Augustine and Aristotle; Aristotle was carrying on a conversation with Plato and Plato with Socrates, the pre-Socratics, and the poets. Proceeding from Descartes we hear the British empiricists, especially Hume, carrying on a conversation with Descartes, and hear Kant being “awakened from his dogmatic slumbers” by Hume. We then experience Hegel in deep conversation with Kant, and Marx conversing with Hegel. Nietzsche (as well as Montaigne and Pascal) can’t be understood outside his conversation with the great Stoic thinkers. And today, Heidegger can’t be grasped outside his struggles with Nietzsche, Kant, and the Greek thinkers… [E]ach of these thinkers was conversing with dozens of contemporaries and predecessors. The ancient texts remained alive because those who came after them, right up to our contemporaries, kept conversing (struggling, arguing) with them—interpreting them…. It was the living conversing with the dead that gave the dead life. If the

conversation ceases, not only the current, most topical texts will be missing, but the early texts will begin to die because they depend upon the living to keep them alive through conversation.

The library stands as a witness to the fact that as a human race we are a single conversation. What is essential to protect our very humanness is the conversation that has gone on for millennia between the generations, the centuries, the constant conversation between the living and the dead…. It is living libraries that preserve texts in such a way that they can become a conversation; and very special libraries, indeed, that preserve these texts as parts of a single conversation.

Another significant step occurred in 1991 with the creation of the Rudolf Steiner Library Newsletter. It began with annotations and short reviews, and gradually included translations of articles from German anthroposophical journals and longer reviews of new acquisitions. In 2008, the content of the newsletter was incorporated into the society’s quarterly publication, Being Human Fred Paddock retired in 2002, and since then Judith Soleil and Judith Kiely have cared for the library, striving both to honor Fred’s vision and to modernize operations so that new generations might discover the library and benefit from its resources. Today, the library belongs to a regional library consortium, the Capital District Library Council, is the proud recipient of a preservation grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and has created an online public access catalog where people around the world can browse the library’s holdings. We invite everyone to join the conversation!

View the library’s catalog online at rsl.scoolaid.net. Questions? Email rsteinerlibrary@taconic.net or telephone (518) 672-7690.

Rudolf Steiner and Contemporary Art

Markus Brüderlin and Ulrike Groos, eds.

Cologne: DuMont Buchverlag, 2010, for Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, 224 pages.

Rudolf Steiner— Alchemy of the Everyday

Mateo Kreis and Julia Althaus, eds.

Weil-am-Rhein: Vitra Design Museum, 2010, 336 pages.

Review by David Adams

These two books are significant exhibition catalogs documenting and elaborating on two large, related, current exhibitions in Germany that represent an unprecedented public presentation and reconsideration of Rudolf Steiner’s work and his influence on art and society today. Both are large-format, hardbound publications in English with extensive color illustrations, and the contributions by multiple authors are concerned with Rudolf Steiner’s work and anthroposophical art from both anthroposophical and non-anthroposophical perspectives.

These exhibitions and publications build on a number of previous publications and sometimes associated exhibitions—primarily in German-speaking countries (all as yet untranslated)—that have risen like a wave since the contemporary art world’s discovery of Steiner’s blackboard drawings in the Goetheanum archives in 1991 by artists (and pupils of Joseph Beuys) Johannes Stüttgen and Walter Dahn. With assistance from Walter Kugler of the Steiner archives in Dornach, these publications and exhibitions have been gradually rehabilitating Rudolf Steiner’s reputation for contemporary art.

For the amount of effort, time, and money that clearly went into these new projects, the results are both exhilarating and, at times, disappointing. Particularly, Rudolf Steiner and Contemporary Art, while raising many intriguing questions, too often lacks adequate or accurate insight into (or, in some cases, even acquaintance with) many aspects of Rudolf Steiner’s work and thought – particularly in many of the contributions by nonanthroposophists.