Rudolf Steiner’s Calendar of the Soul

A 100 Year Celebration of Rudolf Steiner’s Calendar of the Soul for 2012 and Beyond

W ith Deepening Pract ices and Pe rspectives

To Birth Yo ur Sp irit Self through the Seasons of the Soul

with the Calendar of the Soul invites us to listen to an that can be heard within our attentive awakening in the present moment, between past and future, between our soul and and the Creator I of the World. The freshly Rudolf Steiner’s Calendar of the Soul verses includes 100 year perspectives and practices to support us to wakefully cross the threshold from supersensible experience of the content. We can then light from the inner Sun or Star within our own threshold dialogues can then begin to reveal themselves to us .

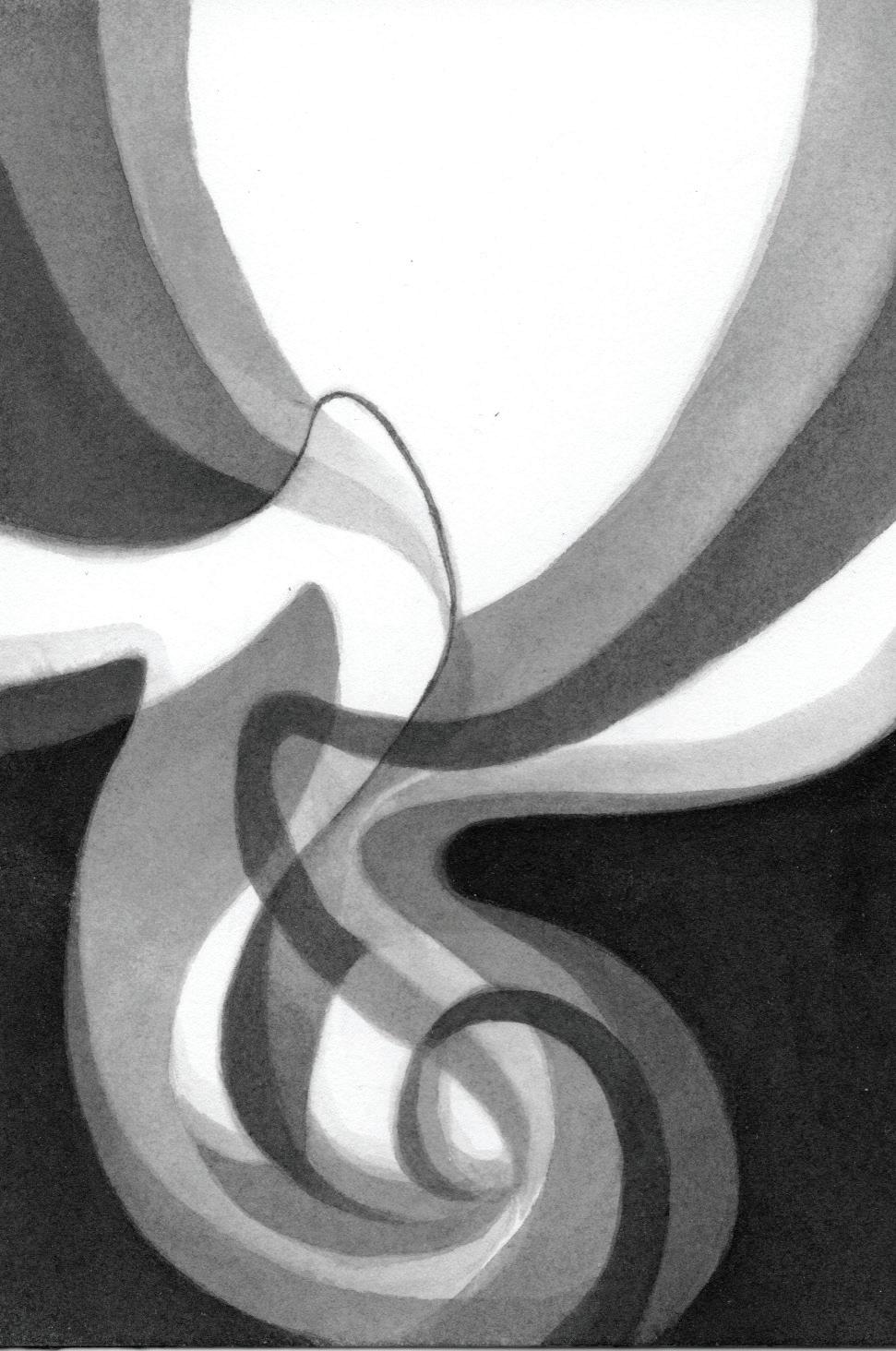

Artistic glyphs show the musical unfolding rhythm of the verses.

Follow Your Guiding Star with the Calendar of the Soul invites us to listen to an unfolding Threshold dialogue that can be heard within our attentive awakening hearts - in the present moment, between past and future, between our soul and World Soul, and between our I and the Creator I of the World. The freshly translated version of Rudolf Steiner’s Calendar of the Soul verses includes 100 year perspectives and practices to support us to wakefully cross the threshold from reading the verses to the supersensible experience of the content. We can then begin to see, hear and intuit the light from the inner Sun or Star within our own hearts. New threshold dialogues can then begin to reveal themselves to us Artistic glyphs show the musical unfolding rhythm of the verses.

and compiled by Vivianne Rael and Henry Passafero. Verses and excerpts by Rudolf Steiner .

Written

and compiled by

Vivianne Rael and Henry Passafero. Verses and excerpts by Rudolf Steinerreceive a Bonus Downloadable Yearly Journal Calendar of 1912. Makes a great gift!

Pre-Order now before Jan. 1, 2013 and receive a Bonus Downloadable Yearly Journal with elements of Steiner’s original Calendar of 1912. Makes a great gift!

www.FifthStream.com

For More Info and to Order Visit : www.FifthStream.com

Dec. 28th, 3-5pm EST

100th Anniversary Conversation, Friday, Dec. 28th, 3-5pm EST

Create Our Future in Light of:

To Heal Our Past, Connect in the Present, and Co-Create Our Future in Light of:

riginal Founding of the Anthrosophical Society ur Past to open Possibility for the Future

The 100th Anniversary of the o riginal Founding of the Anthrosophical Society as we e mbrace the karma of our Past to open Possibility for the Future

nniversay of the Michael Age and Rudolf Steiner’s

The 133 year or 4x33.3 year Anniversay of the Michael Age and Rudolf Steiner’s Breakthrough Thoughts in 1879

Anniversary of Rudolf Steiner’s 1912 Calendar and the Birthing of our fold Spirit Child of Anthroposophia

The 100th Anniversary of Rudolf Steiner’s 1912 Calendar and the Birthing of our indiviudal Spirit Child and the 3-fold Spirit Child of Anthroposophia

the Map to Cross the Gap from now to 2023

The Christmas Conference as the Map to Cross the Gap from now to 2023

(Only $5)

www.FifthStream.com

Sign Up Now to Reserve Your Place ! (Only $5)

www.FifthStream.com

nformation to attend via p hone from any location. A recording will be made available to all registered participants.

You will receive your call information to attend via p hone from any location. A recording will be made available to all registered participants

Support for the Courage to Follow Your Star in Our Emerging Threefold CommonWealth

FIFTH STREAM: Support for the Courage to Follow Your Star in Our Emerging Threefold CommonWealth

the New York Branch of the Anthroposophical Society in America

138 West 15th Street, NY, NY 10011 (212) 242-8945

“The word ‘anthroposophy’ should be interpreted as ‘the consciousness of our humanity.’” – Rudolf Steiner

spirituality, health, education, social action, esoteric research, human & cosmic evolution

self-development, biography, therapies, rhythms & cycles, threefolding, economics

exhibits, workshops, talks, museum walks

Rudolf Steiner’s therapeutic art of sacred movement

music, theater, festivals, community celebrations

free, weekly and monthly, exploring transformative insights of Rudolf Steiner, Georg Kühlewind, Owen Barfield and others

SOME UPCOMING PROGRAMS at 7pm except as noted; details at www.asnyc.org

Lloyd/Lorensen: Sacred Geometry – Wed 11/7, 12/5

Light & Darkness in Charcoal Drawing – Thu 11/8, 12/13

Seasonal Craft Workshops – Sun 11/11, 12/9, 2pm

Rhythms & Cycles of the Logos – Wed 11/14, 12/12

Dr. James Dyson: lecture/discussion – Sat 11/17

Glen Williamson: Mystery of the Logos – Fri 11/30

The Holy Nights, free evening events – 12/26-1/5

Eugene Schwartz: Harry Potter & the Secret Brotherhoods – Sat 1/26

Browse dozens of works by Steiner and many others on education, science, health, art, spirit, biodynamics. Open Tues-Wed & Fri-Sat, 1-5pm.

therapeutic, world, & ‘outsider’ art

The Christian Community is a world-wide movement for religious renewal that seeks to open the path to the living, healing presence of Christ in the age of the free individual. Learn more at thechristiancommunity.org

4 DVD Set

This seminar explores how human prenatal development expresses the essence of human spiritual unfoldment. Understanding the stages of embryological development provides a basis for therapeutic recognition of embryological forces in all later stages of life. This seminar is a rare opportunity to hear a world authority on modern embryology through a unique synthesis of scientific and spiritual principles.

Available exclusively at

PortlandBranch.org

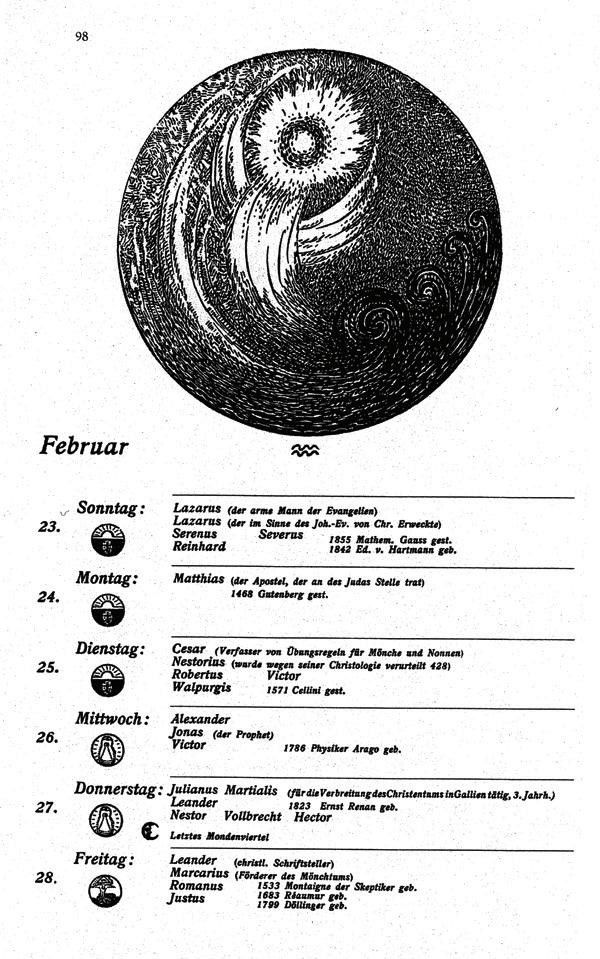

We’re in a season of centennials. We celebrated eurythmy in the Spring issue. This issue we take note of the deeply satisfying Calendar of the Soul which Rudolf Steiner created along with artist Imma von Eckharstein for the year 1912-1913. Half of the original calendar has been relatively unknown, despite a fine facsimile edition in 2003 from SteinerBooks. In this issue we have a treasurable literary essay about the calendar from Gertrude Reif Hughes which first appeared in Orion magazine in Fall 1999. Artist Ella Manor Lapointe (some of whose work you see in the special eurythmy issue) shares her way of working visually with the calendar. Herbert O. Hagens, whose workshops on this subject have been popular for many years, relates the calendar to the autumn Michaelmas festival. And then in “Notes on the Calendar of the Soul ” we have a little banquet-buffet of other approaches and ideas about the calendar, most of which have further substance appearing online.

We have also arrived at the 100th anniversary of the Anthroposophical Society itself. On page 37 “That Good May Become” shares General Secretary Torin Finser’s opening talk at the recent August conference of that name. He works quite esoterically into the special life and character of this society to which most of our readers belong. On page 19 is a very exoteric look at anthroposophy’s place in world history from yours truly. It brings my personal concerns with historical context and suggests why we experience both that “anthroposophy failed” and that it is on the verge of great success.

Also from the conference, “Beyond Our Borders” is filmmaker Jonathan Stedall’s fine talk (very lightly edited for space) on his experience in making the tremendous film, The Challenge of Rudolf Steiner.

This issue features reviews of three books available from the library: Functional Threefoldness in the Human Organism and Human Society, by Johannes Rohen; Medi-

tation and Spiritual Perception , selected and introduced by Gertrude Reif Hughes; and The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus, by Gary Lachman.

In her review of Mr. Rohen’s book, Sarah Hearn examines the basis of the book’s analogy between functional threefoldness in human life processes and in the spheres of social life, focusing on both its creative insights and its limitations. She also notes that the analogy may fall short when the focus turns to “what can we do?” She suggests, candidly, that at the level of activism, there is simply no workable analogy.

Gertrude Reif Hughes’s selection of essays concerning meditation and spiritual perception is a treasure for anyone even remotely hospitable to anthroposophy. All ten of the “Classics” volumes are superb; they serve to remind us how vibrant anthroposophy has been in the last several decades in the English-speaking world, particularly in the USA. Readers should be aware that the entire “Classics” collection is available as a boxed set from the Society and would serve as a gift for a friend (or for one’s self) that will not lose its luster.

Gary Lachman’s book, The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus: From Ancient Egypt to the Modern World , is representative of any number of eclectic or syncretist books today that, while exploring the very questions most vital to any reader willing to listen to an esoteric viewpoint, may seem to fall short in rigor and depth. Such books are urgent in their questioning. They force us to look twice at our own answers, and to seek new forms of resistance to the taboos against meaning that dominate the intellectual landscape today. Reality, as Georg Kühlewind phrased it, is “the last secret,” and may be attained only through more and relentlessly more “conscious questioning.” Lachman’s finely woven storytelling not only stimulates thinking, but persuades us that the habitual assumptions of what Owen Barfield called “an unimaginative man at about ten o’clock in the morning” need not serve as the starting point for those who ask the fundamental question of why there is something rather than nothing.

Frederick J. DennehySample copies of being human are sent to friends who contact us (address below). It is sent free to members of the Anthroposophical Society in America (visit anthroposophy.org/membership.html or call 734.662.9355).

To contribute articles or art please email editor@anthroposophy.org or write Editor, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104. To advertise contact Marianne Fieber at 734-662-9355 or email mfieber@anthroposophy.org.

being human digest covers news and ideas from a range of holistic and human-centered cultural initiatives. Items are brief, suggestions welcome. Write editor@anthroposophy.org or “Editor, being human, 1923 Geddes Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI, 48104.”

Waldorf schools (teachers, students, parents) especially in northern California and folks from Rudolf Steiner College made a special effort to attend the Bioneers conference in October. It’s a long-running annual event held in Marin County north of San Francisco. Bioneers has a biodynamic presence most years, and RSF Social Finance was a sponsor this year. Why Waldorf Works explained:

“‘Bioneers’ are people, of all diversities, working collectively in crafting solutions to the world’s environmental and bio-cultural challenges. At their 23rd Annual National Bioneers Conference, you’ll join global thoughtleaders, experts and advocates in exploring breakthrough solutions for a sustainable world. Education programs focus on ecological literacy and youth leadership. The

conference will feature well-known leaders such as Paul Hawken, Ai-Jen Poo, and Bill McKibben, as well as ‘the greatest people you’ve never heard of.’”

A casual reminder in an email exchange led to a considerable outpouring of reminiscences about John F. Gardner, who would have been 100 on July 3, 1912. He died just after his 86th birthday. The full sharings, a timeline of his life and excerpts from his writings, are at anthroposophy.org under “Articles” along with pictures from his youth to old age.

John Gardner is remembered as person of strength of character, insight, and eloquence; a champion of the Transcendentalist stream in American life and thought; a pioneer of Waldorf education in America; a mentor and friend. His daughter Elizabeth Lombardi writes:

We are a Rudolf Steiner inspired residential community for and with adults with developmental challenges. Living in four extended-family households, forty people, some more challenged than others, share their lives, work and recreation within a context of care.

Daily contact with nature and the arts, meaningful and productive work in our homes, gardens and craft studios, and the many cultural and recreational activities provided, create a rich and full life.

For information regarding placement possibilities, staff, apprentice or volunteer positions available, or if you wish to support our work, please contact us at:

PO Box 137 • Temple, NH • 03084 603-878-4796 • e-mail: lukas@monad.net

lukascommunity.org

“Just as my father could place logs for a fire so that they would have just the right relationship and flow of air, he brought many fine people together and lit the spark of enthusiasm for significant and worthy endeavors. As with his compost piles, he prepared the soil in Waldorf Education for future blossoming and fruiting.”

From Jeff Kofsky: “John was a devoted student of Rudolf Steiner and a master teacher of his work, yet he was unlike any other prominent anthroposophist I have known, for John lived by the Direct Approach. When you eat lettuce and carrots you do not become a little lettuce and a little carrot, he said, you digest and transform substance so that it becomes your own. So be it with the wisdom of those who have gone before. Eat freely, let the world of ideas light up in yourself and express that which would be born in you. This is the essence of Intuition that Rudolf Steiner put forth in his Philosophy of Freedom , and John was a master of it.”

From Nancy DeSylva: “One of the greatest gifts [John] was able to give was his ability to see into the very heart, to instill confidence in one’s ability to do, to overcome, and to live from the Christ-Self. I felt he was able to honor each individual for who they truly are. He helped to awaken that in me, and that is perhaps the greatest

Theater: Kaspar Hauser

blessing I could have ever received.”

From David White: “The whole Waldorf School (of Garden City) was pervaded with a quality hard to put into words, but a place I sensed where I could grow and clarify my goals and ideals… John helped many to enter into a process of becoming their true selves; loving and free in serving.”

From Aggie Mitchkoski: “On one visit I sat at the kitchen table with [John and Carol Gardner]... and proceeded to tell them all the reasons why they shouldn’t think so highly of me. They listened. Then John very seriously said, ‘How can you say anything you’ve done was a mistake when everything you have done has brought you to this point?’ It was a ‘woman at the well’ moment...

From John Bickart: “I think John appreciated the relief from a conviction that he serve almost every person he met as a mirror and a measure of their own inner conviction... Sometimes we could sit back and seriously laugh at life and at ourselves—at how we actually think we know something.”

From Douglas Gerwin (GCWS class of 1968): “Those of us who were his pupils in the classroom experienced facets of his teaching that were largely hidden from the wider public... his biology main lesson in the seventh grade... a Noah’s Ark of the imagination... John’s taste for vaudeville: imagine him in a chorus line of three tall teachers, twirling a cane and raising a straw boater, cracking jokes and singing witty refrains... John Gardner at the blackboard, often well before class began, forming those little gem-like drawings... John remained a personal mentor to many students long after they had graduated. To them he showed... a surprising gentleness and love of nature, a simplicity of lifestyle, a deep interest in the striving of others.”

200 years after his birth on Michaelmas Day 1812, Kaspar Hauser’s story—“The Open Secret of the Foundling Prince”—is coming to life in performance across the USA, in the UK and Canada. Storyteller and acclaimed actor Glen Williamson has created this one-man show to raise to awareness a pivotal figure in European and German history—the abducted infant, heir to a throne, deprived of companionship, movement, language, education. An incredible human story is joined to deeper historical mysteries. The schedule of performances is linked at http://mysite.verizon.net/GlenWilliamson/id3.html

The Rudolf Steiner Mystery Drama performances and conference get stronger each year at Threefold Educational Center in Chestnut Ridge, NY. Producer/director Barbara Renold is helping people engage these lengthy and unusual plays with a cast including some fine professionals and a full conference to penetrate the significance of what is at the same time the personal challenges of

the individual characters, a revelation of karmic backgrounds, and a battle for humanity’s development.

One of this year’s conference speakers, Els Woutersen, drew the parallel with the story of Siegfried in Wagner’s Ring des Nibelungen. “The brave hero Siegfried has to overcome a fierce and mighty dragon. This dragon however exists within himself. It is the dragon of desires, of the lower passions, of everything of a lower nature within him... Overcoming these lower passions and by further purifying himself through the magic fire, Siegfried is able to meet Brünnhilde, who is none other than his higher self who has awakened within him.”

RC Oelhaf reported that “the production was graced with some excellent eurythmy, used to good effect to represent spiritual beings.” Steve Usher spoke to the question of humanity’s choices, to raise the intelligence we have found in nature back to creative sources, or to surrender it to spiritual impulses toward power over others or personal vanity. — www.threefold.org

Louise Drosse Hadley, MA, has organized The Pioneer Valley Muse Group (www.pvmusegroup.org ) to bring anthroposophically-inspired arts and performances

July 15th –

August 4th, 2013

Join native Scots tour leaders as we trace threads of spiritual history in the land- and soul-scape of Scotland. Story, song, eurythmy & informal talks will guide us into the unique cultural climate of this beautiful and infinitely varied country. We will visit Neolithic stone circles of the Outer Hebrides, Highland glens and mountains, the sacred island of Iona, the Findhorn community, Robert Owen’s social initiative at New Lanark, historic and beautiful Edinburgh, and much more.

to her central New England area. “I attribute much of the healing I have experienced in my own life to my encounter with anthroposophical music and arts. It seems to me that these wonderful things are like a hoarded treasure, kept largely in Waldorf schools and anthroposophical circles, and I want to do my part to bring them out into the wider world.” Coming up: A Christmas Carol , with David Anderson of Walking the Dog Theater, “Raphael’s Madonna Images with Lyre Interpretation,” with Channa A. Seidenberg, and “The Incarnation of the Logos: An Epic Tale of Christ’s Coming to Earth,” with Glen Williamson.

I believe that miso belongs to the highest class of medicines, those which help prevent disease and strengthen the body through continued usage. . . Some people speak of miso as a condiment, but miso brings out the flavor and nutritional value in all foods and helps the body to digest and assimilate whatever we eat. . .

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

—Dr. Shinichiro Akizuki, Director, St Francis Hospital, Nagasaki

Anthroposophic nurses have been working independently for many decades across the United States and Canada. However in recent years there has not been a cohesive association. The Kimberton Nurses Association along with Elizabeth Sustick and Anke Smeele has helped launch the North American Anthroposophic Nurses Association (NAANA). The web site is listed under AAMTA (American Anthroposohic Medical Therapies Association, www.aamta.org ). In May of 2012, at the International Physicians Medical Training, five Nurses received their Anthroposophic Nurse Certification. NAANA is in the process of receiving 501c-3 status. We meet regularly via conference call to study, inspire each other, and meet our agendas. Email brigettefitzgerald@yahoo.com for more information.

Dr. Ross Rentea of True Botanica and its new foundation wrote us some months ago. “We have all heard of homeopathic medicines which are made by a process of serially diluting a particular substance—only then do the

Come with us, March 25th 2013 – April 10th 2013, visit the sacred places of this ancient civilization: the Sphinx and Pyramids, the Valley of the Kings, Luxor, Karnak, Dendera, the community of Sekem... Cruise the Nile in a dahibiya, celebrate Easter Day at Abydos!

Contact Gillian: 610 469 0864 gillian_schoemaker@yahoo.com

desired therapeutic effects come about. Also, most of us realize that the majority of anthroposophical remedies are produced by a principle of serial potentization that is very similar, but not identical to, the homeopathic serial dilutions. The problem that has been around for centuries, literally, is to figure out what the appropriate ‘potency’/ dosage for each remedy in each situation should be. It turns out that Rudolf Steiner was asked this question of dosage in the context of a newly developed potentized medicine and his answer was as revolutionary as practical- which his indications usually are. He advised to subject seeds to the various dilutions of the remedy and that the varying growth of the seeds would then show through a growth curve demonstrating the behavior of the diluted substance, and not just in the plant but also in the animal organism. This would allow the finding of the ‘optimal’ solution.”

To help with the lack of research activity, the new True Botanica Foundation is hoping to reawaken the impulse of one of Steiner’s dedicated young associates, Lily Kolisko. “This year an intensive effort has been launched to duplicate and then go beyond the Kolisko experiments in order to address the dosage question. In the past 10 months we have done the work to compile growth curves for over 20 healing substances that are used in anthroposophical medicine. We already have seen some very promising results and anticipate even better data as we continue to refine and advance the process. The growing complexity of the tasks requires not only more equipment but also steadily increasing co-worker hours dedicated to choosing seeds, watering, measuring, etc.

“Recently the first meeting of the Science Advisory Group of the Foundation took place. During a very intense weekend anthroposophical specialists from various fields (medicine-R. Rentea MD, A. Rentea MD, M. Kamsler MD, R. Bartelme MD, P. Hinderberger MD, P.

Barratt MD, K. Sutton MD; pharmacy- T. Heath PhD; biochemistry and laboratory science-J. Erb; homeopathyR. Shaw JD; administration- P. Rentea MHA) began developing a strategy on how to make possible an expanded laboratory where these ideas could be pursued on an ongoing basis. Should we call it the “L. Kolisko Lab”? We hope to develop a wide circle of supporters. A community effort is clearly needed to build up and advance this important work in the lab. This is a not- to- be- missed opportunity to “make a name” for anthroposophy in the science world. Will the ignoring situation of the 1920’s repeat itself? For more information visit us at www.truebotanicafoundation.org. For the Team, Ross Rentea MD ”

Louise Frazier and Wolfgang Rohrs have created a reteat center: “In the beautiful countryside of Vermont, where we offer nourishment for body, soul and spirit in a restorative environment. We provide workshops in food preparation and cookery. In addition, eco-friendly rooms with sweeping views, are available for those living outside the area. Opportunities are given to learn about our delectable vegetarian lifestyle through conversations, observations and participation in our cookery. Our teaching is based on the Cosmic and Earthly nutritional recommendations of Dr. Rudolf Steiner, as applied within the framework formulated by Drs. med. Udo Renzenbrink, Gerhard Schmidt, and Rudolf Hauschka. If you would like to bring a new vibrancy into your days, come for a workshop, a weekend, a few days, or a week where nature and human activity combine for learning, retreat, celebration, and contemplation. Like our notable homemade lactic-acid fermented Garden Splendor vegetables, your perspective will be enhanced!”

The Society’s new database has much improved facilities. Are there listings or networks already of centers

phone: 707-542-1523

email: nurturingarts@sonic net web: www.nurturingarts.org

2012 ~ Art History Training begins from November 6th~like Louise and Wolfgang’s? If not, should we try to help it get started? Let us know (editor@anthroposophy.org ) and take a look at sunrisehillnutritionretreat.com.

GMO Vote in California

Nancy Poer is one of many friends concerned with GMO foods that are not labeled and so deprive consumers of the choice of using or avoiding them. “At the Western States Teachers Conference in February 2012, three of us, all anthroposophists with decades of experience in different fields, a doctor, a biodynamic farmer and Waldorf educator, stood out on the cold city streets to support basic human food rights and the planet. We were gathering signatures for what has successfully became a ballot initiative (Prop 37) for the 2012 California November elections to require the labeling of GMO products in our food supply. This will be voted on by the people and will be one of the greatest stands this country has ever taken for our right to choose healthy food. It will be brutally opposed by the bio tech industry which has pledged millions to defeat it, for it threatens the foundations of their power over what we eat.

“All three of us felt a surreal quality about our endeavors, which could not take place in the warm lobbies of the Anthroposophical institutions nearby as this would have been considered a political action. How did we get to such a strange world that all across the country taking a stand for the right to know what we are eating and supporting healthy food is considered political! To its credit, Rudolf Steiner College, hosted a Food Rights Film Festival initiated by Nancy Jewel Poer, and supported by Harald Hoven, a bio dynamic farmer and teacher, to raise awareness and honor farmers. As a physician, Kelly Sutton has long experienced and spoken out about the GMO health issues she sees in her practice.”

From Stonehaven Farm in Pennsylvania David Lenker connected current food questions with the traditions of the Knights Templar. These inspired and idealist men were to a significant extent the social bankers for Europe until their cruel suppression 700 years ago. “The threat to Templar freedom... appears to have a modern echo: increasing impediments placed on the ability of everyday Americans to freely obtain whole natural organic foods. Large Bio-tech firms continue to promote legislation favoring genetically engineered foods. To maximize profits, these firms encourage agricultural methods that rely on heavy usage of pesticides, weed killers, and chemical fertilizers. In Central PA and elsewhere we see these environmentally toxic methods used to grow genetically modified corn—key ingredient of high fructose corn syrup... Consumers should be given the free conscious decision to buy genetically modified or natural organic food.”

The latest quarterly from RSF Social Finance draws a picture of farms, finance, food, and healthy people and localities. Their topics are “A Poetic of Economics in Agriculture”: rethinking our economic life from the ground up; what lessons can we learn from agriculture and farmers? “Soil, Soul, and Society”: localized agriculture as a foundational activity upon which all humanity depends. Also, “A New American Farmer”: how RSF borrower Viva Farms is helping farm workers become the next farm owner. And “Clients in Conversation”: food justice in Oakland and rural Hawaii. (rsfsocialfinance.org )

From Stuart-Sinclair Weeks, in Concord, MA, came this report back in August about long term efforts to raise

consciousness of the work of the circle around Emerson, Thoreau, and the Transcendentalists. “Since our exchange of mid-June, we in Concord have been able to enact a number of deeds that would serve our greater work here in our United States.

“The July 4th presentation of the ‘Concord Resolution: Toward the Redemption of Our Financial System & Restitution of Our Commonwealth’ at Concord’s Old North Bridge, where its celebrated ‘shot’ was fired.

“The launching of The New World Drama: And Crown Thy Good with Sister- and Brotherhood . Citizens in communities across the country, including Chicago, San Francisco, Santa Cruz, Denver, Tucson, St. Louis, Viroqua, and the Twin Cities themselves have begun to come together to envision ‘scenes’ for the drama.

“And finally Concord Convocation 2012. After 35 years of laying the cornerstones, the convocation concluded with the determination, among those anthroposophists and Michaelic kin who gathered, to take the next step toward the renewal of the spirit of the original Concord School of Philosophy & Literature, 1879-1888, with an extended institute in the summer of 2013. Among others, Bob Richardson, a dear friend, colleague, and author of Emerson: The Mind on Fire, has been an inspiration for this aspiring labor, having offered an outline for a course he would present.

“The following 1884 review by an editor of the Boston Herald speaks to the ‘promise’ of the ‘Concord School.’ ‘To barely exist through these years was something; to gain a hearing was more; to adhere steadily to a high and heroic purpose was more; to be spiritual, without being religious in the sectarian sense, was still more; and, through all these years, to do honest work, to steadily uphold the interests of intellectual and spiritual truth, in the larger sense, has been to do what has never before been done in the history of American thought and letters.’”

Kathy Serafin reported earlier in the year on recognition and support coming toward the Anthroposophical Prison Outreach project of the Society.

“Over the years, we have received inquiries from anthroposophists interested in founding a similar prison outreach program in their home countries. While we have responded with written information, we realized that a practical how-to meeting would be most beneficial and we were encouraged by a longtime supporter to take action in this regard, and we held a presentation/workshop of our program for interested members of the Anthroposophical Society in The Netherlands.

“The results were three fold. The workshop attendants decided to start a similar initiative in the Netherlands, now in the planning and development stage. In turn, we from APO learned about a Dutch drug addiction treatment initiative called ARTA. This program is based on anthroposophical healing principles and is quite effective based on the rate of staying ‘clean’.

“A third result was a complete and humbling surprise to us at APO. The Dutch Anthroposophical Society annually holds a special Christmas Action fundraiser for three selected ‘worthy projects’ in other countries. APO was selected by the Dutch Society board as one of the nominees. As a result, we received from the Dutch Anthroposophical Society members a donation of just over 17,500 euros for the US APO program!

“The Anthroposophical Society in Canada has also expressed interest in starting a Prison Outreach program and members have visited us in Ann Arbor to learn about our program’s workings first hand. We shared our complete manual detailing all aspects of the prison outreach program that was first assembled for the workshop in the Netherlands and now APO is invited to hold a similar practical, ‘How to Meeting’ near Toronto in the fall.

“We are fortunate to be able to help others start a prison outreach initiative in their country and to continue our first commitment of helping US prisoners who earnestly want to change their lives by holding forth the light of anthroposophy behind prison walls. How grateful we are to experience that this same light of anthroposophy touches all of us—in society or in prison, in the US or abroad—through giving and receiving.”

Kathy Serafin, anthroposophyforprisoners.org

Series Editor: Robert McDermott. Anthroposophical Society in America, 2011, 140 pages. Review by Frederick

J. DennehyOne of the best-kept secrets in anthroposophical publishing is the remarkably rich series, Classics from the Journal for Anthroposophy, ten volumes of essays and reviews selected from the long-running publication. As series editor Robert McDermott notes in the foreword to this volume, each collection focuses on a particular theme, “including Rudolf Steiner, anthroposophy, imagination, society, science, Waldorf Education, visual arts, Mani, Novalis, and meditation and spiritual perception.” The series will either remind or alert readers to just how valuable a gift we had for so many years. The essays strike one like an unexpected encounter with an old friend. Some are scholarly and some intimate; they all speak to the question of understanding and practicing anthroposophy from the place where most of us find ourselves most of the time—what the Gospel of John calls “this world.”

In her introduction to this tenth and final volume, Gertrude Reif Hughes focuses on the “how” and the “who” of meditation. The “how” is the praxis —the way to go about the activity that is or should be the center of anthroposophy. The “who” is the question that continually arises in the course of meditation— who do we become when we meditate?

There are fourteen articles in this volume. While none is primarily about the “practice” of meditation, each provides a grounding for practice by helping to turn us away from what Owen Barfield (as Frederick Amrine pointed out in the summer 2012 issue of Being Human), refers to as “the besetting sin of literalism.” That “turning” is a potent achievement.

The first six essays endeavor to locate anthroposophy in relation to other traditions and disciplines. Professor Tyson Anderson, in an address to the American Academy of Religion called “Is Science Relevant for Spirituality?” suggests that the answer is “yes,” but that we have to inform our understanding of science to exclude reductionism or else risk dealing with a science of delusion. True spiritual

science views reality as iconic, a higher form of reading; its approach is strongly feminine, and imbued with heart consciousness. He suggests (surprisingly, I suspect, to the Academy) that the exemplar of the new scientific thinking is Mary Magdalene. As Rudolf Steiner recognized, because she was a woman she was naturally—structurally even—better able to understand something exceptional than could a man. Professor Anderson concludes that Mary Magdalene’s scientia —“thinking of the heart”—was the “radiant point around which the scattered Jesus movement began to coalesce into Christianity.”

In his “Traditional and Modern Elements in the Occultism of Rudolf Steiner,” Robert Galbreath, writing from outside the anthroposophical stream, provides a summary of spiritual science within the tradition of initiatory transformation—in the words of Mircea Eliade, the ontological mutation of the existential condition. The article is bracing in its clarity. Particularly impressive is Galbreath’s account of Steiner’s defense of reincarnation and karma through application of strictly Darwinian principles.

Gary Lachman’s essay, “Rudolf Steiner, Jean Gebser, and the Evolution of Consciousness,” is an acute, detailed comparison of the similarity between Gebser’s “structures” and Steiner’s “epochs” of the evolution of consciousness. Lachman acknowledges that Steiner’s and Gebser’s visions are “very different,” but he is a syncretist. When two separate voyagers discover the same country, he points out, it argues very strongly “for the unknown world’s existence.”

“The Christian Path of Edgar Cayce: A Possible Aspect of Michael’s Activity in America,” by Magda Lissau, Kurt Nelson, and Rick Spaulding, is an assessment of the work of Edgar Cayce through the lens of anthroposophy, particularly through Rudolf Steiner’s characterization of second sight, vision, and premonition as unconscious gifts of Imagination, Inspiration, and Intuition. The destiny of individuals with such faculties allows them entrance into the spiritual world, and their karma protects them from most of its dangers, but not from the danger of misunderstanding. The authors also use Sergei Prokofieff’s Occult Significance of Forgiveness as an initiatory model for understanding the affirmations from Cayce’s study group readings of 1932. The authors suggest that “the higher self of Cayce woke up, in his health readings,” and brought “comfort and healing” as a “gift of love.” They conclude that Cayce’s legacy is “of inestimable value to all those in America who have a serious desire to develop their spiritual striving,” and urge that Cayce’s life be stud-

ied seriously in the light of anthroposophy.

In “Emergence of Ethical Individualism in Science and Medicine,” Karl Ernst Schaefer details what he sees as the appearance of ethical individualism in the second half of the 20th century in four scientists who have had the courage to choose a middle path between polarized factions—those who believe in unimpeded scientific research without regard for moral concerns, and those who believe that scientists should not do any research where findings are likely to raise significant moral dangers— and have stood up to the hostility of their colleagues. Dr. Schaefer suggests that the foundation of moral neutrality in science, dating from the school of Jundi Shapur, may finally be weakening.

Although “Simplicity’s Contribution to a Threefold Society” by Mark E. Smith was written in 1998, it seems even more pertinent today. The essay is a sequel to the author’s “Anthroposophy and Nonviolence,” written three years earlier, and transfers the theme of non-violence to the economic sphere. Mr. Smith’s goal of “voluntary simplicity” in personal economic life is an exemplar of the “middle way,” and a contemporary practical realization of Rudolf Steiner’s “ethical individualism.” But “voluntary simplicity” is not simply a personal prescription; at the heart of the concept is the hidden understanding that individual initiative not only can, but will, contribute to societal evolution.

Ms. Hughes describes four articles as “autobiographical considerations of how the authors experience their meditative life.” The first is Danilla Rettig’s review of And There Was Light, by Jacques Lusseyran, including an excerpt from the book, which describes the special unfolding of the inner life of a man who lost his sight at the age of eight, together with the story of his courageous participation and leadership in the Resistance movement in France.

Alan Howard in “I Think; Yet Not I…,” explores the philosophical underpinnings of thinking, the spiritual activity that fills the state of emptied consciousness that characterizes meditation as Rudolf Steiner described it; while in “A Meditation on Inner and Outer Peace,” Raphael Grosse Kleinmann conjures the sunlight of peace, which he finds intrinsic to genuine meditative experience. And in “The Path of Initiation for the Present Day,” by Paul Eugen Schiller, the author treats meditation in its relation to the practice of Rosicrucian initiation.

The essay, “Meeting with the Dead,” by Albert Steffen, and the review by Tadea Gottlieb of Our Relationship to Those Who Have Died , by Reverend Hermann Heisler,

speak about the relationship of the living to the dead, a subject that requires, in Ms. Hughes’s words, “anthroposophy’s objectivity and detailed spiritual perception.” The cultivation of a genuine relationship to the dead is itself a form of anthroposophical meditation; when properly directed at the so-called dead, this type of meditation may be the key to our most intimate connection with those who have died.

The collection concludes with two pieces that portray the hard-won optimism that is at the heart of anthroposophy. Hermann Poppelbaum, in an article dating back almost fifty years, portrays the “three humiliations” of the human being, ushered in respectively by Copernicus, Darwin, and Freud, in a “Christmas picture” in which the human being is moved to reimagine her eminent position in the cosmos and sees the faces of all the supersensible beings directed toward her.

The final word is from Rudolf Steiner, who in two very short excerpts urges us to understand that through desperate circumstances and inner soul trials a new vision—seemingly impossible in the utter darkness of these moments—will be born.

CLASSICS FROM THE

Robert McDermott series editorAlongside the basic books, these “Classics” collections explore the tremendous cultural and social innovations of anthroposophy and its contemporary development in North America.

Johannes Rohen’s reputation as an anatomist is far reaching: his most famous work, Color Atlas of Anatomy, appeared in seventeen languages. A much lesser-known work, a textbook entitled Functional Morphology: The Dynamic Wholeness of the Human Organism , has received high praise in U.S. anthroposophical circles since its publication in 2007 and served as the foundation for his latest book, Functional Threefoldness in the Human Organism and Human Society.

Functional Threefoldness is an ambitious work. In it, the author endeavors to extend his functional methodology, which he has spent decades applying to the human organism, to identify sound functional principles for a different kind of organism that is arguably just as complex, ailing, and enigmatic: human social life. Rohen is humble in his approach; from the outset he assures the reader he is well aware that “playing with analogies is epistemologically unsound and quickly leads to a dead-end.” He goes on to ensure readers’ interest and attention by essentializing the comparison between these organisms to those based on relationships between functional systems and processes, as opposed to stagnant, singular structures (e.g., cells). As such, it is more the how than the what of the human organism that Functional Threefoldness explores as being relevant and illuminating in regard to a healthy social life. With an approachable balance of brilliance and modesty, it’s clear that Rohen’s ideas are born of deep work and close observation of health, function, and relationship in the human organism. His points of departure easily engage the reader, asking the simple yet urgent questions: what can we perceive here, and what can we learn? He first provides an overview of the threefold organization of the life processes (nervous, rhythmic, and metabolic) of the human organism. This short chapter is refreshingly dynamic even for those fully conversant in the study of anatomy and physiology, yet the content is straightforward and palatable enough for the layperson whose memory of high-school science wobbles. In the following chapter, he offers matter-of-fact descriptions of the threefold organi-

zation of the processes of social life, differentiated as the legal-political, cultural, and economic systems. Rohen describes these spheres as autonomous yet interdependent, as articulated by Rudolf Steiner and others. Thereafter, he offers a functional analysis of our current social systems with an eye toward the healthy and distinct roles of the threefold principles of equality/democracy; cooperation (brotherhood); and freedom in the legal-political, cultural, and economic spheres of social life.

To a point, Rohen, while original in his articulation, generally follows the party line regarding the nature of social life from the perspective of social threefolding (to the modest extent that such a consensus exists!). However, he goes on to forge important new ground and specificity in his analysis of the workings of threefold ideas and ideals. His investigations lead him to justify the existence of an “inner threefoldness” within each sphere of social life that is not merely espoused as a vague concept, but is unfurled in subsequent chapters with great precision and care. Rohen’s method of perceiving symmetry between the functional threefoldness in the human life processes (e.g., the central nervous system, the spinal cord and spinal nerves, and the autonomic nervous system) and in the spheres of social life (e.g., production, distribution, and consumption in economic life) provides a well-organized method for understanding the possibilities for balance and holism in the functions of social life. In his words “this dynamic, yet clear understanding of the human organism can therefore be viewed as an invaluable model for the structuring of the social organism” (p. 45).

But perhaps the pinnacle of his analysis is his delineation of how each of the threefold ideals has a rightful and healthy home within each of the three spheres of social life, just as the human organism’s systems are active according to functional principles, which are adapted to respective sub-systems. Accordingly, while the cultural sphere exists under the flag of freedom, Rohen makes sound argument for specific cultural functions and institutions that require freedom to be their guiding principle through and through, and others for which the principle of cooperation or democracy must be active alongside the principle of freedom. A more detailed treatment of these pictures goes beyond the scope of this review. Suffice it to say, however, that anyone seeking more specific imaginations of Steiner’s picture that each sphere should have its “own administration” will be pleased with Rohen’s offerings, at the very least as food for thought, and at most as entirely amenable to Steiner’s indications.

Rohen does a commendable job articulating his vision without falling victim to the potential stasis that charts and schematic diagrams can pose to a reader. His descriptions maintain the sense of living complexity inherent in the systems of his analysis. And, in good pedagogical form, he seems to encourage his readers to think through his analysis, providing ample explanation and helpful supplementary examples. At times, Rohen seems naturally to follow Steiner’s pedagogical indications regarding characterization, stating that “the making of many definitions is death to living teaching” (Steiner, R., Study of Man, Rudolf Steiner Press, 2011). Rohen offers many characterizations of the principles and ideals of social life, and multiple contexts in which to examine them at work. In this way he provides his readers with the opportunity to “battle their way to understanding these connections” (p.99), which he believes is the backbone of understanding the basic features of pathology in social life and mustering the necessary courage and initiative to heal society.

Rohen’s method is at once scientifically diligent and artistic, poetic and metaphorical. In one instance he calls the reader’s attention to the oft-promoted coupling of the economic sphere and the metabolic process (given their respective transformation of substances, etc.) But he swiftly points out that the social organism is “fed” by the education, ideas, and innovations of the cultural sphere— without which we would “starve.” Employing further artistry, Rohen presents lively pictures of threefoldness within the legal system, such as characterizing the legislature as the central social networker and “heart of society,” sensitive to the needs of the people in the same way the heart monitors blood supply to a given organ and reacts accordingly; or describing the “social breathing space” provided by the judiciary1 and the reintegration process that the executive, law-enforcement functions can enable for social deviants, just as the immune system carries out reintegration processes (here he also draws an analogy to certain types of white blood cells that “patrol” the organism in search of foreign bodies). Rohen continuously brings fresh analysis and imagination to the nature of social life and to threefold ideas for those with or without prior acquaintance with these fields.

Indeed, in addition to a thorough treatment of the spheres of social life and their functions and relationships,

1 Here, Rohen emphasizes the role of freedom alongside the legal system’s dominant principle of equality—in this way his contention is related to Steiner’s indications that relate the judiciary functions to freedom and the cultural sphere.

Rohen specifically tackles a few hot-button issues that generally elicit conviction and/or confusion from people on both sides of the traditional political spectrum. One such issue is the nature and role of money, which Rohen relates to the circulation of blood, providing an informed diagnosis of the current monetary system’s pathology, most notably of the commodification of money itself and its status as the “unfair competitor” of real goods and services. In response to these realities, he provides clear and eloquent descriptions of the proper role and function of money in a threefold social organism. In his analysis here and throughout, Rohen is diligent in citing both anthroposophical and non-anthroposophical sources, both contemporary and time tested. However, while he points to some successful examples of regional currencies from the 1930s, he makes practically no mention of the more than 2,500 alternative currencies currently in existence, which have varied degrees of success and equally wideranging (usually unconscious) alignment with threefold principles. It is also worth clarifying that in the U.S., from which he draws various examples regarding money, regional governments are forbidden to issue regional currencies, but local or regional cultural entities (e.g., nonprofits) can do so, with some guidelines and restrictions.

Rohen outlines other examples of “social pathology,” including the commodification of land, labor, and capital, and offers a brief treatment of the state of healthcare, education, and other cultural services. In addition, he points to automation, deregulation, and other culprits of our social unhealth. In each of these cases, Rohen paints a bleak picture of the current state of affairs and of the pathological growth in already unhealthy systems, and illustrates how these tendencies are stark aberrations from the robust and healthy functional threefold pictures that he has outlined. Although Rohen offers some important suggestions for the redemption of our ailing systems, he fails to mention what seem to be some of the most hopeful examples of positive change, such as community land trusts and worker-owned co-ops (though he does mention profit sharing with employees).

Generally, this is more an academic treatment of relevant themes than a call to action; a beautiful map of what’s possible, but without a clear navigation tool or vehicle for getting there. To his credit, Rohen clearly qualifies his intentions from the outset, stating that “how such things should be tried out in practice is beyond the scope of this book.” Yet the book’s final inquiry, “What Can We Do?” almost begs the reader to engage in just that ques-

tion. Rohen’s strongest advice is, first and foremost, to have a clear understanding of how social processes work.

Perhaps after heeding his recommendation, one could turn to the advice of another author (and activist extraordinaire), whom Rohen references with admiration: Nicanor Perlas. While Rohen offers Perlas much praise, he also states that “so far, unfortunately, civil societies are not sufficiently organized to constitute a third force capable of bringing about healing processes in modern society” as Perlas proposes. However, since the publication of Rohen’s book, we’ve experienced more and more conflict, bloodshed, and the censorship of various freedoms around the world, not to mention a historic economic crisis. In the same time frame, however, Nicanor Perlas ran for the presidency of the Philippines, and more recently initiated a new civil-society organization, MISSION, which is showing signs of becoming just this kind of much-needed third force in society. In addition, millions of people worldwide have come together in solidarity as part of the Occupy movement. If we can marry this emergent cultural force with the wisdom and knowledge of social processes and threefolding that Rohen so vividly describes, perhaps we can take some real steps toward healing. But perhaps here the analogy with the human physical organism falls especially short. Affecting systemic, positive social change requires the free, conscious, inner and outer activity of human beings working together out of insight, and for this—and perhaps just as well— there is no analogy.

Functional Threefoldness brings a new voice and perspective to many of the long called-for reforms and new ideas of threefolders and some of the larger circle of individuals and organizations seeking social renewal. Rohen’s depth of understanding of the human organism is reflected in this intricate and thoughtful contribution to understanding social life, the social illness we live with as a global community, and the path to creating a healthier world.

247 pages. Review by Frederick

J. Dennehy

J. Dennehy

Gary Lachman, founding member, songwriter, and bass player for the rock group “Blondie,” became a fulltime writer in 1996. He focused initially on the history of the 1960s counterculture, but by 2003 had found a different interest. Lindisfarne Press published his Secret History of Consciousness: A Semi-Popular Account of Reductive, NonReductive and Esoteric Understandings of Consciousness, 1 a study of the evolution of consciousness that explores the thinking of Goethe, Bergson, Ouspensky, and Jean Gebser, as well as that of Rudolf Steiner and Owen Barfield.

Not altogether surprisingly for someone who has made his way through The Ever-Present Origin (Jean Gebser’s evolutionary sequence of changes in types of consciousness from the archaic to the magical, the mythical, the mental-rational, and the dawning of the integral), what fascinates Lachman is the notion of consciousness history as a palimpsest in which the old coexists with the new.

Last year, Lachman turned his attention to the enigma of Hermes Trismegistus, the “thrice great one” who may have lived in ancient Egypt; may have been a syncretic union of many Hellenistic esotericists; or may not have existed at all. Readers hoping to find the true identity of Hermes Trismegistus will not find it here. Rather, they will find an account of Lachman’s own notion of the Hermetic way: a melding of what is valuable from the most fundamental esoteric traditions (“as above, so below”) and mainstream thinking. Here, as in A Secret History of Consciousness, he sketches out the wandering history of an idea. He traces the meandering stream of Hermetic thought from its fabled beginnings in Egypt, to the murmur of its underground music in Hellenistic and medieval times, to the roar of its resurgence in the Renaissance.

Then comes the plunge. Lachman is perhaps at his best recounting the near disappearance of Hermeticism following the relentless scrutiny of the scholar Isaac Casaubon, who demonstrated convincingly that the supposedly ancient texts regarded as the core works of Hermeticism were pious forgeries. But whatever it is that animates the central texts of Hermeticism—the multivolume Corpus

1 Available from Rudolf Steiner Library, as is Gebser’s The Ever-Present Origin.

Hermeticum and the renowned Emerald Tablet —reappears despite Casaubon. Lachman recounts the resurfacings of Hermeticism in the new forms of Rosicrucianism, Freemasonry, the Cambridge Platonists, German and British Romanticism, Theosophy, anthroposophy, and the best of New Age thinking. Hermes, it seems, may be unidentifiable, but is still immortal.

If Lachman is sometimes short on analysis, he is a wonderful storyteller. The cumulative effect of The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus is to shine a light on the manifestations of Hermeticism through the ages and to make a case for its centrality. It provides the reader with generous starting points for further reading and an impetus for personal research.

Because there is little that can be said with any degree of certainty about Hermes Trismegistus, and because the Corpus Hermeticum is dialogic, obscure, and stubbornly resistant to translation, most of The Quest for Hermes Trismegistus is discursive, exploring associated themes such as Egyptian cosmogony, alchemy, and various accounts of the journey through the planetary spheres (which Lachman compares to the anthroposophical account of the period between death and rebirth). Lachman also looks at subjects more loosely related with his theme, such as experimen-

tation with nitrous oxide and mescaline; Paracelsus; John Dee; Robert Fludd; and a parade of modern philosophers.

Lachman is strongest in his account of the “rediscovery” of Hermes by Marsilio Ficino in the Italian Renaissance and his fate in the aftermath of the Reformation. He is less able to elicit the meaning of Hermeticism, relying upon the sweeping distinction between gnosis, with which he associates Hermeticism, and episteme, with which he associates reductive knowledge. Many readers are likely to find his conclusions wanting. His fascination with the “hypnogogic state,” which he misidentified in his biography of Rudolf Steiner [2007; available from RSL] as the state of consciousness Steiner employed for spiritual research, persists in this book. We remain basically unenlightened not only about Hermes Trismegistus himself and the principal texts attributable to him, but also about Hermeticism, which seems for Lachman, finally, to be a vaguely widened perspective that includes the outside world in both its synthetic and natural manifestations and anything in consciousness that has an undefined “spiritual” character.

Lachman’s urge to connect invariably trumps his urge to commit. We are left intrigued, stimulated, but hungry for something more nourishing—like anthroposophy.

This two part DVD is available on the website: £15 + post & packing or as a download rudolfsteinerfilm.com

Anthroposophy is a hundred years old. The word is older, but it has found its particular meaning in the work of Rudolf Steiner. To render it from Greek merely as “the wisdom of the human being” is today highly ambiguous; how much wisdom does the human being show? In 1923 Rudolf Steiner said that the word should be interpreted as “the consciousness of our humanity.” And the next year he described it as a path from the mind-and-spirit in the human being to the mind-and-spirit in the cosmos, immediately and crucially adding:

It arises as a need of the heart.

In this short review we will not look at the 1912 action of members of the German section of the Theosophical Society in forming an Anthroposophical Society. Our interest is in drawing a larger picture of anthroposophy, and the society devoted to it, in human history and culture, and today, here in the USA.

Should we expect it to have accomplished more? A rather small group of people has carried a large sense of responsibility for humanity’s future. They have shown many failings, but have persisted and endured. Alongside that crucial fact, two others appear: First, the great foundation for their work was the spirit and idea of Europe, and it failed, catastrophically, in World War I. Second, according to the threefold gesture Rudolf Steiner described as “how one becomes an anthroposophist,” there are millions of anthroposophists alive today, outside and perhaps ignorant of the movement calling itself “anthroposophy.”

In other words, “anthroposophy” seems like a failure—but one which Steiner and others just refused to accept almost a century ago. And yet today it is a present and future success which we are struggling to recognize.

Today it’s polite to play down Europe’s role in world history, but it was through Europe that physical, commercial, military, political, scientific, technological, and cultural globalization were set in motion. And until 1914 European powers were the masters of the world. The USA

and imperial Russia became Europe’s huge, awkward wings; but small countries beginning with Portugal took control of vast areas of the planet. European rule unfolded relentlessly, harshly, but the aggressive outward side of it was partnered by an inner cultural triumph, the development of modern science. Out of nature’s sub-basement poured such vast hidden forces that, tamed by machines, we could provide well for every human being alive today, if that were our choice. But to start telling these stories, of the ships and guns and trade, the observations and experiments and hypotheses, would take many, many pages.

What matters is that by 1900 old Charlemagne’s European children had actually reached the threshold of becoming partners with the creative powers of the cosmos. The early adventurers’ stolen or created wealth had fed a culture approaching the sublime.

So at the historical moment when Rudolf Steiner became active, Europe had become capable and worthy of leading the development of a world culture. Slavery had been abolished. Reformers sought to care for the poor and elevate the displaced peasants who were now the urban industrial proletariat. The days of privilege by birth-right were fading fast (and near forgotten over in America). The magical experience of reading was open to all. Art had begun to see and speak to everyone. Romanticism reaffirmed the meaning of the individual. The novel, the canvas, and the opera created overwhelming alternate realities: imagination awakening imagination.

Science had revealed vast invisible fields of forces stretching to the stars. “Matter” was recognized to be not quite what we naively take it for. Evolution now told us we had endured a vast process of development not mentioned in the Bible. Psychology was probing the inner life, finding unknown regions, determined to conquer the soul just like another hemisphere. If Christian theology held back, Mme. Blavatsky’s Theosophy offered ancient Hindu-Buddhist concepts to raise thinking into worlds of consciousness higher than the human. Europe was even beginning to listen to the world. Debussy learned from the Javanese gamelan, Picasso from African masks.

This Europe was an idea and an ideal. Imagined esoterically, it was a chorus of archangels—a chorus of cultures and languages reaching up together to shape planetary destiny. It was a harmony of diverse voices hymning an exalted purpose. And with the failing and falling away of old social forms and traditional understandings, it was demanding a new and higher stage to rise onto.

All that was missing was a way of understanding, ob -

jectively, just what the human signifies in the cosmos, and what our choices signify for our future. It is in this situation that Rudolf Steiner appears, in a modest workingclass family of lower Austria. What he eventually brought would have made no sense, gained no traction, either outside Europe or earlier in its history. It was a consummating step in a thousand years of cultural becoming.

But in August 1914 Europe set about to destroy itself in “the Great War.” By Christmas 1916 the last chance to stop the war on the old terms, within the “idea of Europe,” failed. A year later Tolstoy’s Russia fell to an atheist regime enflamed with class hatred. By 1920 imperial Germany was shattered socially and economically, and Austria-Hungary dissolved. The surviving young of all countries were outraged by their elders’ stupidity. Left and right were murderously at each other’s thoats. Americans who helped win the war “over there” for the Western powers took a victory lap and went home again to isolate.

The world into which Rudolf Steiner was bringing his vision and his tools for a higher cultural development—that world just vanished. The possibility of his anthroposophy’s rising with Europe, as its highest and most progressive imagination, no longer existed. Anthroposophy would have to find new possibilities in a world that would continue to destroy itself, and tens of millions of human lives, for many decades to come.

Italy went fascist in 1922. Germany succumbed in 1933, Spain in a hideous civil war from 1936 to 1939. Then German arms swept across most of continental Europe—until Hitler unwisely invaded the USSR.

The aftermath from 1945 forward was a choice of politically benign but culturally corrosive consumerism from the USA—or a long harsh winter under the commissars. In 2012 the once world-conquering Europeans celebrated the simple fact that they are no killing each other with a Peace Prize to the European Union.

Individuals from Europe can be as idealistic and influential as individuals anywhere else. But their shared cultural vision has been stunted, and their sense of a world responsibility is largely buried under the shame of colonialism and its cultural brutality. The point for us is that Europe since 1916 was not a platform from which an “anthroposophy” could graciously make its way in modern civilization. The USA may have a vaudeville culture

and brutal means of global force projection, but despite the economic rise of China, India, Brazil, the world is still looking for leadership from America.

Rudolf Steiner was asked about this in 1919 (see CW 194, lectures of 14-15 December). He had already spoken three years before of an Anglo-American “economic world empire.” Now, questioned by the first English visitors since the armistice, he noted that the defeated countries would have no further role to play as nations. Britain and America would build their empire “like a force of nature.” To help balance out the materialism which is their natural and karmic contribution to world culture they would have to bring forth new spiritual impulses.

The Anthroposophical Society in America was formed in 1923, but as late as the 1950s its members were still speaking about a “catacomb period”—when the early Christians met secretly and literally underground in imperial Rome. And despite German being America’s largest single ethnic background, there was now a cultural stigma attached to everything German. The defensive posture required for anthroposophy’s survival in Europe was also emulated in the USA; perhaps we just assumed that “that is how anthroposophy is done.”

So if it had depended on the Anthroposophical Society alone, anthroposophy in America today would be invisible. Two related impulses have succeeded, however. One is the increasingly able translation and publishing of Rudolf Steiner’s work, so that spiritual seekers and openminded cultural activists can discover that he is relevant if not still well ahead of the times. The other factor, helped by the publications and by staunch immigrants from Europe, is applied anthroposophy, the “practical” initiatives especially in education, agriculture, health, and special needs. Today anthroposophy in the USA is actually wellrepresented by a very substantial infrastructure of human services. They are widely recognized as outstanding in their goals and very credible in accomplishment. Most often society members initiated and carried this work, but there has been, so to speak, a hole in the doughnut when the question is asked: “So what is this anthroposophy?”

With all good will, anthroposophists have often gagged on that simple question, or thrown up a cheerful roadblock like, “Have you got a week?” One purpose in naming this publication being human was to suggest the option of saying right away that “anthroposophy is about being human.” No one is turned away by such a response.

It can flow on easily with words like, “And my connection with it is...” Self-development? My kids’ education? Health? Nutrition? Healing the Earth? Understanding where we’re headed? Try “being human” next time.

But there is a deeper story to “what is anthroposophy” which we need to explore. That story lives in the phrase we use as a synonym, “spiritual science.” This “spiritual science” is a plausible but inadequate translation of the German word Geistes-Wissenschaft (hyphenated here only for clarity). Wissenschaft is a freer term than English “science”; it suggests “creative intelligence” rather than just the cold, hard facts. And Geist is a word which points to mind and intellect and spirit. When Rudolf Steiner said words which we translate as “thinking is already highly spiritual [Geist-lich],” his claim was supported for a German-speaking mind by the broader meaning of Geist.

For English-speakers today, “spiritual science” may be a pleasantly surprising contrast in thoughts. Or it may be a laughable oxymoron that places anthroposophy in the company of religions like Christian Science and Scientology. What anthroposophists are bizarrely unaware of is the fact that this term Geistes-Wissenschaft was coined in 1883 by a prominent German thinker named Dilthey and has become the standard word for what Englishspeakers call “the humanities.”

Dilthey noted that natural science (Natur-Wissenschaft) had been established by Francis Bacon on brilliant foundations which led to its stunning success. But Dilthey’s interests—history and new disciplines like sociology and psychology—were a bad match for Bacon’s science, which sought to exclude human feeling and intentionality from its framework. Dilthey called for a science (Wissenschaft) of mind-and-spirit (Geist); he saw this being founded on an understanding of the individual human spirit. Given the right basic principles and researches, a whole great second pole of “science”—human sciences—could be opened up alongside nature science.

Rudolf Steiner actually did this foundational work. His Philosophy of Free Spiritual Activity justified the individual human mind-and-spirit as foundation for a view of reality. His How to Know Higher Worlds is a preparatory manual for the researcher in this new field. Theosophy gives the “lay of the land.” An Outline of Esoteric Science takes the new science back to the beginning of time.

Academic thinkers did not recognize the significance of his early works, and eventually he found his audience in the Theosophical Society and went public with his esoteric researches. Steiner ended by revealing an “inner”

science of evolving humanity. Though it radically challenged established and conventional modern thought, if Europe had not collapsed, it might have been understood.

So what is anthroposophy? It really is “about being human” and we can speak of it just that simply. And this “science of mind-and-spirit” is a revolutionary cultural paradigm shift. Anthroposophists will have to acknowledge and clarify and defend it in those terms, too.

Where do the simple being-human and the new cultural paradigm meet? In individual human development: in our choice to become more fully and more consciously citizens both of the physical world we have mastered (by Bacon’s shrewd tactics), and of the metaphysical-spiritual world where we can find our enduring being.

Individuals matter in anthroposophy’s future, and so does geography. Celebrating Rudolf Steiner’s 150th anniversary last year gave many anthroposophists in the USA a strong sense of opportunity around the core mission and ideas of anthroposophy—its whole civilizational perspective on humanity’s future. This is very timely. If Europe was once like a “chorus of archangels” raising the global vision and culture, since 1945 the eyes of the world have been on the USA. In our outer role as world power, the single world power now, we often do not earn the world’s respect, and our past is replete with abuses. But in the inner American impulse to form one nation out of free individuals, wherever they come from, and to afford all persons an opportunity to manifest their potential—in that unique organic principle the world senses an enduring ideal. By accepting the breadth of our differences, Americans reach up to that same high level of the universally human which the idea of Europe once achieved.

Anthroposophy is not needing to be led globally by US-Americans, who could not match all its rich development in Europe. But over here, in the inner America where humanity often sees a real generosity of spirit, Americans must help anthroposophy grow strong and open and credible. This will come both out of Rudolf Steiner’s work and its worldwide development, and out of our work with compatible American roots and branches. Is that possible? For sure. There is nothing inherently strange to Americans in “the consciousness of our humanity.” And a path from the mind-and-spirit in the human being to the mind-and-spirit in nature, the planet, the cosmos—that, too, arises “as a need of the heart” in a great many Americans. Emerson, Bronson Alcott, Mar-

garet Fuller, Whitman, Thoreau, Dickinson and many more have been singing this great anthem which was heard before by the original inhabitants of this continent.

Steven Usher wrote recently about a “culmination” of anthroposophy at the end of the 20th century (posted at anthroposophy.org ). I agree with him that the success of our initiatives in the late 1990s was indeed a culmination. But do we imagine things stopping there? Only if our perspective stays within “the anthroposophical bubble,” where no word is heard unless uttered by Rudolf Steiner and no success counts unless it wears our colors. Perhaps that is what Manfred Schmidt-Brabant, the last president of the General Anthroposophical Society, was seeing when he spoke at Michaelmas 2000 of the “occult imprisonment of the Anthroposophical Society.” A grim phrase. The efforts we make into the world are turned back on us, he said. Why? Because we do not take others’ capacities and intentions seriously enough?

The “consciousness of our humanity” should assist us, not prevent us, in seeing beyond ourselves. In many places but especially in the USA a huge new, non-sectarian, non-traditional, spirituality blossomed from the 1960s forward. What Steiner had called for in 1919 as a counter-balance to our materialism actually appeared. By the end of the 1990s, psychographic researchers (who assess and measure the spread of personal beliefs, values, and ideals) had identified tens of millions of Americans who “care deeply about ecology and saving the planet, about relationships, peace, social justice, and about authenticity, self actualization, spirituality and self-expression.” These are neither cultural traditionalists nor “moderns,” and the research shows them growing: “In 1995, 23.6% of the US adult population, or 44 million adults... In 2008, 34.9% of US adult population, or 80 million adults.” Yes, this is the “values cohort” dubbed the “cultural creatives.”

Creating culture globally is central to the mission of anthroposophy, along with the self-development (or “selfactualization”) required for such a culture to appear and endure. The link to “cultural creatives” is even clearer. Rudolf Steiner described “how one becomes an anthroposophist” (on 2/13/1923, in Awakening to Community). He describes a process essentially identical to “Becoming a Cultural Creative,” the second chapter of The Cultural Creatives, published in 1999. There are three steps:

1. Our heart (perceptive feeling ) tells us that the world we are trying to engage has something (or

many things) seriously wrong in it.

2. We turn inward and look upward in our thinking to find higher insights and values to will allow us to understand the situation.

3. We turn back outward with these insights, with a will to try to heal things in the world.

This threefold gesture in human consciousness, Steiner implies, is the movement-in-consciousness by means of which we can recognize the being he calls Anthroposophia . And researchers who knew nothing of Steiner’s work recognized this gesture, her signature, in the hearts and minds of tens of millions of Americans in the 1990s.

The time span of a hundred years is reinforcing, according to Steiner’s research. So the anniversary of the founding of the original Anthroposophical Society should be wind in our sails. We can also take note of the “cosmic day,” a 72-year span, one degree measured by the movement of the starry heavens. These cosmic days seem to measure out human lives and impulses. The Bolshevik regime in Russia lasted, as Steiner said it would, for a cosmic day: 1917-1989. A cosmic day after Rudolf Steiner said in 1919 that additional spiritual impulses would have to arise in the West, American researchers began finding evidence of a new spirituality among tens of millions of “cultural creatives.” A cosmic day after his great “practical” initiatives (1919-24), Waldorf schools and biodynamic farms and CSAs and Camphill villages were sprouting across the USA. Tens of thousands of “cultural creatives” have been finding and embracing these initiatives.

Emerson, too, observed the Days.1

Daughters of Time, the hypocritic Days, Muffled and dumb like barefoot dervishes, And marching single in an endless file, Bring diadems and fagots in their hands.

To each they offer gifts after his will, Bread, kingdom, stars, and sky that holds them all.

I, in my pleached garden, watched the pomp, Forgot my morning wishes, hastily Took a few herbs and apples, and the Day Turned and departed silent. I, too late, Under her solemn fillet saw the scorn. What a difference a day makes, if we accept her gifts.

First published in Orion magazine, Autumn 1999.

Maybe it’s because I’m an academic, or maybe it’s the famous ability of mortality to concentrate the human mind—or perhaps it’s just a personal idiosyncrasy—but I know that I feel a clearer connection between my own inner life and that of the planet in autumn than at any other time of year. The waning light poses a challenge. Will I be able to compensate for the growing cold and warm to my tasks? Am I ready? Fall asks something of me. Spring, whether because it’s so beautiful or, for a teacher, so impossibly burdensome, overwhelms me every year. But fall, with all its warnings and wanings, stirs me to take initiative, make a contribution, find my own powers and use them. Fall and winter open a space for me to fill.