POTENTIALITY FOR MIDAN AL-TAHRIR AS A MONUMENT AND A MATRIX, IN THE ABSENCE OF A BUILT URBAN FORM An examination of the site’s extended history of political uprisings and instability. Antony Fenhas : 490480496 Architectural History Theory 3 : BDES3011

Table Of Contents

Intro

History of Tahrir Square

Archetypes And Prototypes

Tahrir Square As A Monument

Networks And Assemblages Of Tahrir Square Conclusion

Bibliography Appendix

3 4 6 7 9 11 12 12

Intro

The monument, that which stands prominently out of the ground as a reminder of past narratives and the immutable grip of the present regime, is often understood as an opposition to the notion of the interwoven Matrix. What constitutes what a urban monument and matrix are is investigated through the scope of the site of Tahrir Square. The site in downtown Cairo, Egypt has an extended history of political demonstration and unrest, most notably during the 1950’s against the English occupation, and more recently, 2011 and 2013 during the Arab Springs revolution1. The aim of this research is to investigate the potentiality of envisaging a monument that is not necessarily a built form but a site, a network of activity that exceeds temporality. One that may host a number of different monuments over its history whilst nevertheless still encapsulating the same meaning, an assemblage of parts that are not additive but conjugating.

The Monumental urban form in question is not single monument, but four that have existed on the same site over a period 150 years, with close attention paid to the vital gaps between each monument. The site of Midan al-Tahrir (Tahrir Square) has the potential of simultaneously existing as both a monument and a matrixial network of fragments, symbolically representing the totalitarian regime whilst remaining as a space of liberation and revolution. Through the examination of the architypes of the mountain and the forest, the notion of the monument and its co-analogous matrix, the research seeks to dissolve the boundary between the two, and discover a liminal intermediate zone, a monumental assemblage that emerges through the withdrawal of the other. This is done through the analysis of the key themes of Monument, Matrix, and Mimesis, whereby each notion is broken down to its etymological root in order for a sophisticated understanding to be built up.

Architectural History Theory 3 3

1 El Dorghamy, Yasmin. “Tahrir Square, Evolution and Revolution.” Rawi Egypt’s Heritage Review. Accessed 2nd of May 2021. https://rawimagazine.com/articles/tahrirhistory/

Above: 2011 Arab Springs Revolution, Cairo. Photo Credit: Ed Ou

History of Tahrir Square Revolution and Political Unrest

Sitting on the edge of the Nile river, the square later to be known as ‘Midan Al-Tahrir’ (Tahrir Square) began it’s life in the 1870’s after a bridge was constructed connecting the island of Zamalek to the expanding Ismailia quarter1. The site became known as ‘Kasr Al-Nil Square’, named after the former palace that existed on the site, which was later replaced by Barracks. Ten years later the minister Alu Pascha Mubarak executed the new city of Ismailia, renaming the square to ‘Midan Al-Ismailia’2.

The square saw it’s first monument on the site during King Farouq’s reign in the 1930’s, where a roundabout and a garden were constructed, with a grand pedestal placed in the middle of the square with the intention of placing a statue of the former noble Khedive Ismail on it. The statue was never placed however and the pedestal’s fifty years life before its removal saw the square grow in significance after mass protests became a feature of the site, one of the most notable of these protests was the 1951 strike against the British occupation in Egypt. The construction of the colossal ‘Mogama’ government building opposite the site in 1953 saw the square being renamed for the third time in its short history, coming to be known to it’s present name of ‘Midan Al-Tahrir’, translating to square of liberation commemorating the departure of the British from Egypt2.

Sixty years on and the square lived up to its name, rising to international fame across the globe following the January 25 mass protests. The garden and fountain that had existed on the site were destroyed during the early stages of the protests, allowing the site to become a stage for the political unrest in the following years. The strikes that were sparked by years of corruption over Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year dictatorship, saw 18 consecutive days of protests and clashes between the people and the police. Left with no other option, the president stepped down leaving the country in the hands of the military, promising democratic change and open elections.

4 Architectural History Theory 3

Left: 1930 Tahrir Square Pedestal Monument. Photo Credit: Rawi Archives

1 El

Dorghamy, Yasmin. “Tahrir Square, Evolution and Revolution.” Rawi Egypt’s Heritage Review. Accessed 2nd of May 2021.

2

Al Sayyad, Nezar. “History of Tahrir Square.” Midan Masr. Accessed May 2nd 2021.

Less than two years later following the newly elected non-secular government, a second revolution took hold over the country bringing out millions of protestors into the streets, calling for a secular democratic government that lives up to its demands. The president ‘Mohamed Morsi’ was overthrown on July the third, 2013, leaving country once again in the hands of the military. After the second election in under 3 years, the former director of the military was elected as the president of the country. A controversial new monument was erected on Tahrir Square later that year to commemorate the martyrs of the 2011 and 2013 revolutions. The monument constructed by the acting government body however was erected by some of the same figures that oversaw the killing of the protestors by the state during the protests. This act was seen by some as an attempt by the state to hijack the legacy of the uprising and its aftermath3. A quote by Ahmed Maher, the leader of the 6 April movement that helped lead protests in 2011, said that “a Tahrir memorial was long overdue, but that it should not have been built by the same people who had created the need for a memorial in the first place”4.

Finally at the start of 2020, the site’s fourth monument was erected to commemorate the site’s extended history of liberation, and the individuals that lost their lives fighting for it. This time however the state funded monument was received with mixed emotions, seen by some as a successful memorial, others however as another attempt of erasure of the country’s past5.

Architectural History Theory 3 5

Left: 2013 Controversial Monument During Construction. Photo: Drew Brammer

3

Brammer, Drew. “New memorial in Tahrir Square stirs controversy.” Egyptian Independent. Accessed 4th of May 2021.

4

Kingsley, Patrick. “Tahrir Square memorial is attempt to co-opt revolution, say Egypt activists.” The Guardian. Accessed 4th of May, 2021.

5 a“Cairo’s

Tahrir Square given facelift decade after Egyptian revolution.” Middle East Eye. Accessed 6th of May 2021.

Architypes and Prototypes The Mountain Versus The Forest

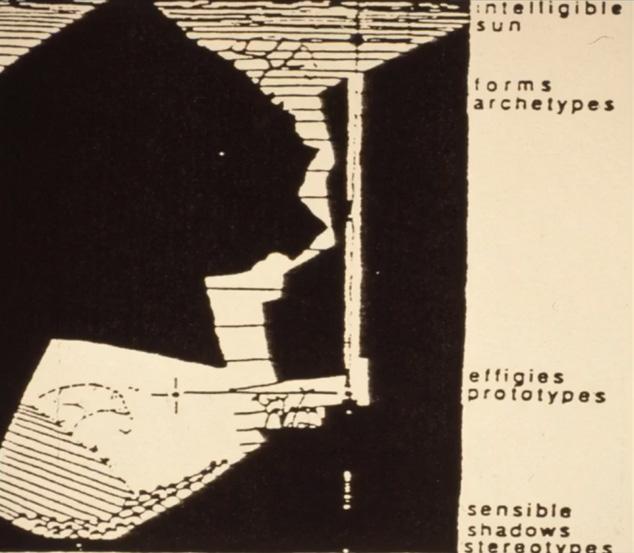

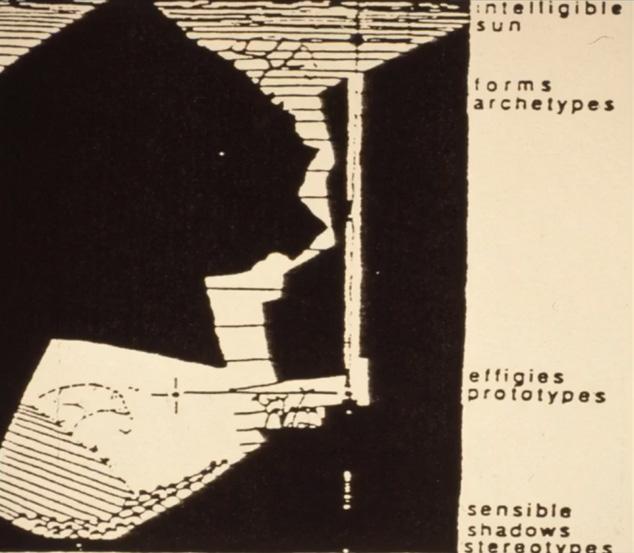

By first analysing the themes of the monument and its co-analogous matrix through the lens of Plato’s four levels of reality, we can begin to understand the individual’s perception of truth and knowledge through their perspective. These four levels of reality are broken down in Socrates’ cave allegory to the intelligible light above, representing truth and knowledge, which provides light unto the archetypal forms, descending to the mimesis of the prototypal effigies, whose shadows reflect on the wall as the stereotypes. Through this notion, we can link back to the idea of the mountain as the archetypal monument, that which comes forth to reveal itself out of the Earth. Similarly, the forest can be broken down as the archetypal Matrix, existing through the interconnected networks and systems of relationships. The relationship between these two ideas, one of prominence versus the interwoven can be understood as the allegory of the mountain revealing itself out of the forest, two oppositional notions nonetheless simultaneously coexisting through the withdrawal of the other.

The tectonics of Plato’s four levels of reality can thus be directly related to the site of Tahrir Square, whereby the intelligible light representing absolute truth existing above the monumental

site, the prototype of the archetypal mountain. The shadow of these monuments are thus stereotyped by the individuals and collectives through their personal conception of the site, a conception that is twice removed from reality. This detachment from the absolute truth is brought about through the rich network of narratives and histories existing on the site, interwoven matrices, a mimesis of the forest.

Left: Tectonics Of The Allegory Of The Cave. Credit: Michael Tawa

6 Plato. The Republic, 1930.

6 Architectural History Theory 3

Tahrir Square As A Monument Prominence, Remembrance & Authoritarianism

It is first essential to breakdown the definition of a monument, determine its links to remembrance, but also the tied notions of discerning and weighing up which simultaneously co-exist in the term. Monument can be etymologically derived from the root *MEN, meaning to think, weight up and discern, but is also cognate with the root *PIE, meaning to remind, or recollect. Taking this understanding of the term monument and applying it to the site of Tahrir Square in Cairo, a site that has hosted not one but four monuments over the course of its history, allows us to have a deeper understanding of how the site in itself can be understood as but not limited to a monument. The name ‘Tahrir’ translates to liberation, a term that was coined during the 1930’s for the square by King Farouq commemorating the departure of the English from Egypt2, a name has remained relevant to square long after its birth.

By applying this understanding of the monument, we can link the idea of a monument to that of the notion of remaining, a site of remembrance that allows us to appreciate that which remains, or what comes forward out of the Earth. This effectively creates a link, one that brings past narratives into the present, which are hence carried forward shaping the future, allowing the monument to exist across temporalities. It is no coincidence therefore that a relationship exists between buildings and their use throughout human history as shrines and memorials, acting as reminders of what’s departed, taking the shape of memorials for deities, or political, financial and

utopian monuments7. The creation of monuments therefore can act as a powerful tool in the hands of the state, collectives or individuals, allowing for a careful selection of which narratives or ideologies are carried forward into the present, and future, and which are forgotten8.

2 Al Sayyad, Nezar. “History of Tahrir Square.” Midan Masr. Accessed May 2nd 2021.

8 Cassin, Barbara. History Theory, Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon. Translated by Stecen Rendall, Christian Hubert. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014: 439-450

Architectural History Theory 3 7

Above: Power Imposing State Monument, Sydney. Photo Credit: Author

7 Boullée, Etienne. Architecture, essay on art. Translated by Sheila de Vallee. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1778-88

This power of architecture and urban forms as a form of expression of power to symbolise new political and social ethos is outlined in Maria de Betania’s essay “Totalitarian States and Their Influence on City Form”9. Betania delineates a major feature of totalitarian regimes is the necessity for the demolition and reconstruction of historic sites on quest for monumental urban forms in service of political ideology. The superimposition of monumental urban forms to induce fear and submission has repeatedly been seen throughout history in cities such as Moscow, Rome, and Berlin. The power of Monuments however extends past fear, but can be used as a tool to impact the physical, social, and cultural structure of a city, an erasure of past histories in place of new political and social values.

The political uprisings of the Arab springs in 2011 saw the destruction of not only the physical monumental urban form that existed on Midan Tahrir from the late 1980’s, but also the breaking down of the political and social ideologies embedded by the state. The first few days of the protests saw the destruction of the garden and fountain that existed on the square opposite the grand government building. A loaded act that symbolised the clearing of the past totalitarian regime, allowing the site in itself to become the stage for the revolution, a monumentalisation of the blank canvas that stood as a public square.

8 Architectural History Theory 3

9 De Betania Cavalvanti, Maria. “Totalitarian States and Their Influence on City-Form: The Case of Bucharest.”

Below: Tahrir Square During 2011 Revolution . Photo Credit: Pedro Ugarte

Networks And Assemblages Of Tahrir Square Tahrir Square As A Matrix

To put the concept of Midan Tahrir Square as a monument aside and examine the site through the lens of the Matrix, allows us to build a complete picture of this complex site. The term Matrix is derived from the late Latin term ‘Womb’, but also ‘mater’ meaning mother, source or that of the origin, and is a cognate etymon of ‘measure’. The Etymological root of the matrix defines it as that what enables, the womb or origin which makes possible. This allows the matrix to be understood as a site of emergence, whereby the edge, limit, or laymor is exceeded resulting it to marginate, go beyond the margin and emanate.

The second notion which the matrix can be understood in is that of a system of relationships, whereby links and connections are constantly activated within a system, whether those systems are of politics, religion or culture. This network of gestures or process of assemblage works with the potentiality of fragments to combine and recombine, conjugating in different ways, fundamentally changing the concept by the way it conjugates with other assemblages10. Emergence is thus the resultant condition of the assemblage11, explored in Deleuze and Guattari’s assemblage theory, concepts emerge through the conjugating process of assemblage . This networking of fragments in the matrix therefore delineates what fragments are for, rather that what fragments are of, resulting in the potential for the concept to become something else.

Taking these two notions we can now begin to understand the site of Tahrir square as not only a monument, but how it acts as a matrix through its assemblages. This notion is investigated in Zvi Bar’el’s “Tahrir Square, From Place to Space”12 exploring the history of the unrests that took place on the square, and how these protests transform the site from a physical place, into a symbolic space, and finally into an abstract space. These physical places become sites of what Henri Lefebvre terms ‘spatial practice’, whereby lovcalised action defines meaning for that location, irrespective of its original intended use. Spatial practice is ascribed as the transformation of a

10 DeLanda, Manuel. Assemblage Theory. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari, “What is a concept,” in What is Philosophy. Translated by Janice Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994: 15-60.

Zvi Bar’el. “Tahrir Square, From Place to Space: The Geography of Representation.” The Middle East journal 71, no. 1 (2017): 9–22.

Architectural History Theory 3 9

11

12

Above: Protestors During The 2011 Revolution. Photo Credit: Moises Saman place through the appearance of its ‘actors’, the term actors defining not only the collective taking action but also the individual subjects as much as they are always members of the group seeking to appropriate the space in action. Bar’el concludes that the evolution of these actors from mere subversives to a resisting force that becomes a revolutionary movement required the physical appropriation of Tahrir square. It is this appropriation of physical place that transforms the square into a different kind of representative space, one that embodies the people’s hegemony defining new values surpassing the existing regime.

This recurring metaphor of the appearance of actors effectively links back to the notion of the physical clearance of the square in order for it to become the stage for the revolution. Whereby these actors both as individuals and collective represent the potentiality of fragments, acting as a system of networks to create assemblages. It is thus through the conjugating process of these assemblages that the emergent phenomena occurs, fundamentally changing the concept that is Tahrir square, ascribing new meanings and values to the physical place.

10

Conclusion An Uncertain Future

Tahrir square, a paradoxical site simultaneously acting as a symbolic space of the totalitarian regime whilst simultaneously remaining as a site of liberation and revolution. A point of intersection between networks of histories, narratives, politics, cultures and collectives existing in a liminal transitory condition, on the verge, an ambiguous state between a monument and a matrix. Over a period of 150 years four separate monuments have existed on the site, each attaining to be a symbol of the liberation of the country however none living up to the grand repute of the square. Initially hosting a pedestal that was never complete to commemorate the noble Khedive Ismail, followed by a fountain and public garden, destroyed by protestors, and replaced with a controversial state funded memorial to the martyrs of the revolution, and finally the now standing grand obelisk. Whether the country will ever break the recurring pattern of falling under authoritarian regimes after each revolution remains undetermined. Some signs of the newly elected government signal its path to repeat the same mistakes previous totalitarian regimes undertook, including the construction of monumental urban forms in service of political ideology. Oppositions to that signal the rapid growth of the country’s economy and infrastructure as symbols of a new beginning however. Critics such as Zvi Bar’el argue, after every wave of protests, the square returns to its original status as a hegemonic symbol of the new regime6, leaving many to predict the country’s uncertain future. One thing that does remain however, is the monumentality of ‘Midan al-Tahrir’ in the absence of a built urban form, but one that is resides in the shared memories, narratives and culture of the peoples past, present and emerging.

The destruction of the once standing monument on the site during the 2011 revolution symbolised the beginning of the fall of the long standing regime. The clearance of a site allowing it to emerge as a stage for the protests, played out by its actors through their networks of assemblages. A monument and an emergent phenomenon that comes out of the Matrix, both states existing simultaneously through the withdrawal of the other.

Architectural History Theory 3 11

Above: Midan al-Tahrir Currently. Photo Credit: Mohamed Abd El Ghany

Bibliography

De Betania Cavalvanti, Maria. “Totalitarian States and Their Influence on City-Form: The Case of Bucharest.” Journal of Architectural and Planning Research 9, no. 4 (1992): 275-286. https://www. jstor.org/stable/43029085

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari, “What is a concept,” in What is Philosophy. Translated by Janice Tomlinson and Graham Burchell. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994: 15-60

DeLanda, Manuel. Assemblage Theory. Edinburgh, Edinburgh University Press, 2016.

Plato. The Republic, 1930.

Foucault, Michel. What is Enlightenment. New York, Pantheon Books: 1984, 32-50.

Zvi Bar’el. “Tahrir Square, From Place to Space: The Geography of Representation.” The Middle East journal 71, no. 1 (2017): 9–22. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/90016288

Ghonim, Wael. Revolution 2.0 : the Power of the People Is Greater Than the People in Power : a Memoir Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

Cassin, Barbara. History Theory, Dictionary of Untranslatables: A Philosophical Lexicon. Translated by Stecen Rendall, Christian Hubert. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014: 439-450

Boullée, Etienne. Architecture, essay on art. Translated by Sheila de Vallee. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale, 1778-88

Kingsley, Patrick. “Tahrir Square memorial is attempt to co-opt revolution, say Egypt activists.” The Guardian. Accessed 4th of May, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/nov/18/tahrirsquare-memorial-co-opt-egypt-revolution

Brammer, Drew. “New memorial in Tahrir Square stirs controversy.” Egyptian Independent. Accessed 4th of May 2021. https://egyptindependent.com/new-memorial-tahrir-square-stirs-controversy/

El Dorghamy, Yasmin. “Tahrir Square, Evolution and Revolution.” Rawi Egypt’s Heritage Review. Accessed 2nd of May 2021. https://rawi-magazine.com/articles/tahrirhistory/

D. Kirkpatrick, David. “Egypt Erupts in Jubilation as Mubarak Steps Down.” The New York Times. Accessed 2nd of May 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2011/02/12/world/middleeast/12egypt.html

Al Sayyad, Nezar. “History of Tahrir Square.” Midan Masr. Accessed May 2th 2021. http://www. midanmasr.com/en/article.aspx?ArticleID=140

“Cairo’s Tahrir Square given facelift decade after Egyptian revolution.” Middle East Eye. Accessed 6th of May 2021. https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/egypt-tahrir-square-cairo-renovation-arabspring

12 Architectural History Theory 3

1. 3. 2. 4. 5. 9. 6. 7. 8. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15.

Appendix

Annotated Bibliography

Totalitarian States and Their Influence on City-Form: The Case of Bucharest –Maria de Betania Cavalvanti 1.

Maria de Betania links the demolishing and reconstruction of historic sites in place for monumental urban forms as a major feature of totalitarian regimes, through the case study of socialism in the city of Bucharest, Romania. The author delineates the power of architectural and urban forms as an expression of power symbolising new political and social values, as well as it’s use induce fear and submission through the state’s power over the people.

This source is relevant to my research as it outlines how monuments have been used historically to impose authoritarian regimes over citizens, not only physically, but socially and culturally as well. Supporting the notion of the impossibility of separating architectures and politics, where every action induced on the built environment is inherently political.

2.

The Republic - Plato

Socrates’ dialogue authored by Plato in the ‘Republic of Plato’, outlines Socrates’ cave allegory, a representation of education, as well as the ideal society, broken down into four levels of reality. These four levels are the intelligible sun, providing light unto the archetypal forms, descending into the prototypal effigies, whose shadows reflect on the wall as the stereotypes. The allegory alludes to the platonic idea of light representing truth and knowledge, opposed to the ignorance of darkness where the slaves are twice removed from reality.

This source is relevant to my research as I am to touch on the idea of mimesis, the monument as a prototype of the archetypal mountain, which can often be stereotyped through it’s interpretation. Challenging the platonic idea of truth existing solely in light and clarity, I aim to reveal the richness which can be encompassed in gloom, and the gloaming, the ambiguous twilight zone.

3.

Architecture Essay on Art – Etienne-Louis Boullee

Boullee begins by deriving architecture’s relationship to art, linking architecture as a form of art and science, to it’s impossibility to be created without first having a profound knowledge of nature. The author then goes on to break down different monumental urban and architectural forms including the Basilica, Theatre, and Palace of Justice. Boullee attributes architecture’s sole ability to ascribe metaphorical imagery to monumentalise buildings of power, justice, and cultural significance.

Boullee’s analysis of the Palace of Justice as a building having a majestic and impressive effect over it’s viewer / citizen alludes to monumental urban forms created under totalitarian regimes. Use of scale, masses and metaphorical imagery loaded with symbolism are made to create this sense of majesty and dominance, not only its surroundings but also it’s citizens, it’s grandness depicted as “made to appear to be part of heaven”.

Architectural History Theory 3 13

Tahrir Square, From Place to Space: The Geography of Representation – Zvi Bar’el4.

Zvi Bar’el Briefly outlines the history of Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo, it’s former uses, and critical relationship to the Arab springs of 2011. More importantly, Bar’el delves into the transformation of the square from a physical place, to a symbolic space, and finally falling into an abstract space throughout the process of the protests. Linking the events that transformed Tahrir Square to Henri Lefebvre’s concept of a space’s transformation through the physical appropriation conducted by the ‘actors’ acting as a collective.

The source effectively links the events of the 2011 Arab Springs in Cairo to the abstract idea of transformation of physical place into symbolic space. Thus questioning what constitutes this transformation and its connection to the networks of individuals and collectives operating within that site, a site of what Lefebvre terms spatial practice.

5.

What is Enlightenment – Foucault

Michel Foucault’s ‘What is Enlightenment’ breaks down the idea of enlightenment and questions whether this ongoing process, rather than a phenomena has released humans from a certain state of immaturity. This is done through comparatively analysing Immanuel Kant’s concept of the ‘Ausgang’ (Exit or way out) alongside Charles Baudelaire’s idea of Modernity. Foucault challenges Kant’s notion of the Enlightenment as an exit from this state of immaturity, a way out that is characterised in ambiguous manner. Baudelaire’s concept of modernity is outlined as not a form of relationship to the present, but a mode of relationship established with oneself.

This source is relevant to my research as Foucault breaks down the boundaries between the relationship of the present to the past, and future. Delineating Enlightenment’s inability to release use from our state of immaturity, alluding to the richness of ambiguity encompassed in the idea of the gloom.

6.

Revolution 2.0: The power of people is stronger than the people in power - Wael Ghonim

Wael Ghonim’s Revolution 2.0 is an autobiographical recount of the 2011 Egyptian revolution, Ghonim being the manager of the Facebook page which sparked the January 25 protests, depicts the story firsthand from the lead up to the revolution. Taking place in Tahrir Square, the peaceful protests lasted 18 days and saw millions of citizens mobilize to the streets in demand for an end to the dictatorship, leading to the downfall of Hosni Mubarak’s three decade long presidency.

The source depicts the densely multilayered politics and events which lead to start of the Arab Springs, a network of interweaving issues and goals, with no clear leadership of the movement nor end term goal. A term repeatedly used throughout the account is that of bringing down the ‘Pharaoh’, a link to the country’s past but also present, and future.

14 Architectural History Theory 3

Dictionary of Untranslatables – Bernard Cassin7.

Cassin analysis the notion of history as a narrative, an assemblage of facts to fabricate stories and histories, with a potential of assembling these facts in a multiplicity of ways to form different narratives. Leading to the notion of construing of facts, an act done by various nations to shape narratives through their individualised perspective that may not necessarily align with those of other nations.

Cassin’s reading of the science of history links to the notion explored in the concept of the gloom, that of breaking down of classifications and separations, brought about by enlightenment. The examination of these individual perspectives excludes many other alternative stories, whereby the ambiguity between fact and narrative is dissolved, resulting in a false perception of what our collective history is, one that is constantly construed in a temporal frame.

8.

Assemblage Theory – Manuel DeLanda

DeLanda Breaks down the notion of assemblage theory, a concept given it’s definition by Gilles Deleuze, and Felix Guattari. Exploring the notion of matching and fitting together a set of components, an ensemble of parts that mesh together well, not as a product but a Process. Contrasting relation of interiority and exteriority, intrinsic and extrinsic, the author sees assemblage as actively linking parts together and forming relations between them.

This source is relevant to my study of the notion of Matrix, linking assemblage theory as a way of working with the potentiality of fragments, to combine and re-combine. Conjugating in different ways parts that are not necessarily uniform either in nature or origin.

Architectural History Theory 3 15